Jen was Defence. No way was she going to get stuck with caring stuff: Environment, Education, Health... Girls always got these. Jen was having none of it.

“But do you know anything about defence?” Sonia was First Minister, because of course. She would be Head Girl one day. You just knew it. She’d been like that since primary – since nursery, probably. This lunchtime she sat on the edge of the teacher’s table, hair swaying and legs swinging. Her candidate virtual Shadow Cabinet leaned on windowsills or sat on desks. Sitting at desks would have taken deference too far.

“No more than the current Defence Minister did for real,” said Jen. She was underselling herself, a bit. Her grandfather had a shelf of paperbacks with faded covers and yellowing pages, inherited from his grandfather, who had been in the Home Guard: great-great-granddad’s army. The old Penguin Specials had tactical suggestions. The principles were sound, the details out of date. Where now could you get petrol, or glass bottles? Jen knew better than to ask Smart-Alec. Still, there was plenty of open source material.

“I can pick it up from background. Learn on the job, like Sajid Anwar did. That’s the whole idea.”

Sonia pretended to give it thought. “Yeah OK,”she said. She ticked the box and moved on: “Mal? I’m thinking Energy for you?”

He looked pleased. “Aye, fine, thanks.”

“Morag: Info and Comms...”

It was a Fourth Year project. The Government worried about the young: mood swings between sulking and trashing, around the baseline of having lived through the Exchanges. Live on television, even a limited nuclear war could generation-gap adolescents, studies showed. Rising seas deepened radicalisation. Civic and Democratic Engagement education challenged school students to govern a virtual Scotland, using real-time data, and economic and climate models wrapped in strategy software. The authorities burned through ten IT consultancies and tens of millions of euros before a Dundee games company offered them an above-spec product for free: SimScot.

Oak Mall connected Greenock’s decrepit high street to its desolate civic square. In the years after the Exchanges it flourished, literally: hanging baskets beneath every skylight, moss shelving on every wall, planters every few metres. When the floor flooded, the mall’s own carbon budget couldn’t be blamed.

Two days into the SimScot project. Sonia, Jen, Mal, Jase, Dani, Morag and a couple of others walked down the hill to the mall after school and mooched along to the Copper Kettle. Cruise ships arrived weekly on the Clyde like space habitats from a more advanced culture. Today the Star of Da Nang was docked at Ocean Terminal, a few hundred metres away. Masked, rain-caped and rucksack-laden, Vietnamese tourists ambled in huddles, glanced at display windows in puzzled disdain and bought sweets and souvenirs at pop-up stalls. The humid walkway air was itchy with midges. The cafe had aircon and LED overheads and polished copper counters and tabletops.

“Temptation’s to treat it as a bit of a skive,”said Sonia. She drew on her soya shake, lips pursing around a paper straw. “Check the grading, and think again.”

Everyone nodded solemnly. “Still feels like a waste of time,” said Jase. He had plukes and pens.

“You’re Education,” Sonia pointed out. “Make me a case for dropping the requirement.”

Jase looked as if he hadn’t thought of that, and made a note.

“It’s like having to come up with answers to your dad’s questions,” said Mal. He put on a jeering voice: “What would you do instead? Where’s the money going to come from? Yes, but what would you put in its place?”

Jen laughed in recognition.

“Whit wid ye dae?” said Morag.

“Build a nuclear power station at Port Glasgow,” said Mal. He gestured at the tourists outside. “Make a fortune recharging cruise ships.”

Sonia flicked aside a blond strand. “Make me a case.”

“No Port Glasgow though,” said Morag. The town was adjacent to and even more post-industrial than Greenock. She was from there and kind of chippy about it. She considered options upriver. “Maybe Langbank?”

“Speaking of nuclear,” said Jen, “I’d start by taking back Faslane, subs and all, and then annexe the North of England as far as Sellafield.”

“Well,” said Sonia in a judicious tone, “it could be popular...”

They all laughed. The English naval enclave across the Clyde from Greenock was a sore point.

“But not feasible,” Sonia went on. “For one thing, breaking international law breaks the rules and gets you marked down. Like I said, Jen, what I want from you is exactly what the brief asks for: an independent non-nuclear defence policy.”

“I thought we had one already,” said Javid.

Jen had been doing her homework.

“Yes,” she said, “if being small and defenceless is a policy.”

“Who’re we defending against?” Jase demanded.

“Well,” said Jen, “that’s the big question...”

“Not for you, it isn’t,” said Sonia. “Javid’s the Foreign Secretary.”

They bickered and bantered for a bit. Jen complained about toy data, and any real research getting you on terror watch-lists. Morag muttered something about a workaround for that. She picked a moment Sonia wasn’t looking and slid an app across the table from her phone to Jen’s.

A few minutes later Jen’s phone chimed.

“Home for dinner,” she said. “See you tomorrow, guys.”

Morag winked. “Take care.”

Jen walked briskly up a long upward-sloping street of semi-detached houses. In one of them, at the far end, her family and five other households lived more or less on top of each other. Postwar, fast-build housing had been promised. The gaps in the streets showed the state of delivery.

A male stranger’s deep voice just behind her shoulder said: “Hi Jen, would you like to talk?”

“Fuck off, creep.”

She leapt forward and spun around, shoulder bag in both hands and ready to shove. No one was within three metres of her. She smiled off glances from others in the homeward-hurrying crowd.

“Sorry, Jen,” said a woman’s voice, behind her shoulder. “I’m still getting used to this.”

Again no one there.

“Stop doing that!”

“Doing what?”

“Talking from behind me.”

“Sorry, again.” The voice shifted, so that it seemed to come from alongside her. “It’s an aural illusion. Your phone’s speakers enable it.”

“Not a feature I’ve ever asked for. Smart-Alec: settings.”

“Smart-Alec is inactive.”

Jen took out her phone and glared at it.

“Who are you?”

“I’m the new app your friend gave you. Call me Lexie, if you like.”

“OK, Lexie. Now shut the fuck up.”

After dinner Jen pleaded homework and retreated to her cubicle. She slid the partition shut, cutting off sound from the living-room, and sat on her bed, back to the pillow and knees drawn up. She flipped the phone to her glasses and started poking around.

“Lexie” turned out to be an optional front-end of Iskander, which wasn’t in any app store. It had much the same functions as Smart-Alec – an interface to everything, basically – but despite the clear allusion in its name it had no traceable connection with Smart-Alec’s remote ancestor, Alexa. Right now, it was sitting on top of all her phone’s processes, just like Smart-Alec normally did. This wasn’t supposed to be possible.

She had the horrible feeling of having been pranked, or hacked. Morag didn’t seem the type to pull a stunt like that. Jen had taken for granted that Morag was savvy enough not to share malware.

Jen took the glasses off and dropped her phone, watching it fall like a leaf to the duvet. She did this a few times, thinking.

“Lexie,” she said at last, “can Smart-Alec hear us?”

“No,” said Lexie.

“What are you?”

“A user interface.”

Jen muttered bloody stupid literal – “An interface to what? What is Iskander?”

“Iskander is an Anticipatory Algorithmic Artificial Intelligence, colloquially called a Triple-AI.”

“How’s that different from Smart-Alec?”

“This app has different security protocols. Also, Smart-Alec can give you what you ask, and suggest what else you might want. Iskander can anticipate what you will want.”

Jen put her glasses back on, and poked some more. The app’s source was listed, in tiny font on a deep page, as the European Committee. That sounded official.

“OK,” she said, somewhat reassured, “show me what you can do. Anticipate me.”

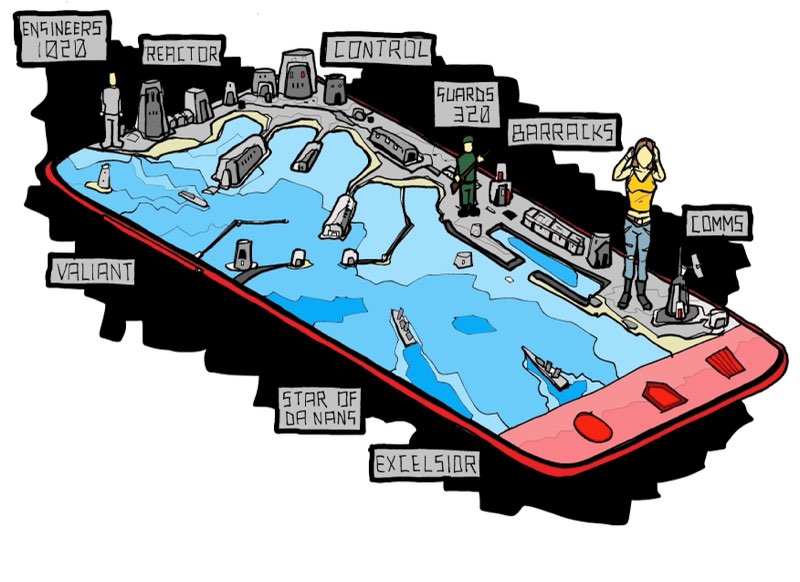

A map of Scotland unfolded in front of her. Ordnance Survey standard: satellite and aerial views, some of them real-time, overlaid with contour lines, names, symbols, labels...

Then as her gaze moved, the map highlighted all the military bases and hardware deployed in and around Scotland. Whenever her glance settled on a site, the display drilled down to details: personnel, weapons, fortifications, security procedures and on and on. She closed her eyes and swatted it away.

“I shouldn’t be seeing this!”

“You wanted information on which to base an independent non-nuclear defence policy,” said Lexie, frostily. “As you’ll have gathered already, no such policy exists. Scotland is a staging area and forward base for the Alliance. The Scottish defence forces – land, sea, and air – are nothing but its auxiliaries and security guards.”

Jen had always suspected as much, and had heard or read it often enough. What she’d just seen gave chapter and verse, parts list and diagrams.

“You don’t have to refer to this specifically to produce a much more comprehensive and realistic policy than you could from public information,” Lexie went on.

“Fuck off,” said Jen.

She tried to delete the app, but couldn’t. This too wasn’t supposed to be possible. Smart-Alec came back to the top. The classified information vanished. Iskander still lurked, to all appearances inactive – it didn’t even show in Settings – but ineradicably there, a bright evil spark like an alpha emitter in a lung.

Between classes the following morning, Jen passed Morag in the corridor. “Fight corner,” she said. “Half twelve.”

Morag didn’t look surprised.

Between the science block and the recycle bins, a few square metres were by accident or design outside camera coverage. It was where you went for fights and other rule-breaking activities. At 12:30 Jen found a couple of Juniors snogging and a Sixth Year pointedly ignoring them while taking a puff. All three fled her glower. Morag strolled up a minute later. They faced off. Morag was stocky. She walked, and carried her shoulders and elbows, like a boy looking for trouble. As far as Jen knew, this manner had so far kept Morag out of any. She had weight and strength; Jen had height and reach. She’d done martial arts in PE. Morag played rugby.

Mutual assured deterrence it was, then.

“ Whit’s yir problem, Jen?”

“What the fuck d’you think you’re playing at?” Jen demanded in a loud whisper. “Oh, don’t give me that innocent face! You know fine well what I mean.”

“You did ask. Kind ae.”

“I did no such thing. How could I? I had no idea. Where did you get it, anyway?”

“Friend ae a friend,” said Morag, glancing aside with blatant evasiveness. She grinned. “Had it for a while, mind. It’s great! It’s like a cheat code to everything.”

“Yeah, I’ll bet. Meanwhile you’ve turned me into a spy and a hacker.”

“No if you don’t tell anyone. I sure won’t.”

“Christ! What about inspections?”

Morag laughed. “It knows when to hide.”

Jen scoffed. “Does it, aye?”

“I should know,” Morag said, smugly. “I’m Information.”

“Is that how you got it? Researching information policy?”

“No exactly. Never you mind how I got it.” She spread her hands. “Come on, it’s all over Europe. It was bound to turn up here eventually.”

“Sounds like a new virus or a new drug.”

“It’s kind ae both.”

“And who’s spreading it? Who started it?”

Morag shrugged. “The Russians?”

“We should report this.”

“What good would that do? It’s still out there. The cops know about it already.”

“We should report it to the school, then. It could land us in big trouble if we don’t. ”

“You’re the Defence Minister,” Morag jeered, “and you go crying you’ve been cyber-attacked by the Russians? No a good look, is it?”

“Not as bad as the Information Minister spreading it.”

“Don’t you fucking dare.”

“Dare what?”

“Tell on me.”

“That’s not—”

“Better fucking not.” In each other’s faces, now.

Someone shouted “Girl fight!” People gathered. Jen and Morag stepped back.

“But if you pull a stunt like that again,” Jen swore as they parted, “I’ll have you.”

She considered it, even as Morag swaggered away. Jen had never been so angry at anyone. She could turn Morag in, report the matter to the Police, just fucking shop the bitch and serve her right.

“You don’t want to do that,” Iskander murmured, uncannily in her ear. “You don’t know what else they might find on your phone.”

Jen stood stock still and stared out across the rooftops and parks to the Firth of Clyde and the hills beyond. A destroyer’s scalpel prow cut the waves towards Faslane. Kilometres away in the sky a helicopter throbbed. The Star of Da Nang floated majestically downriver, red flag flying. Smoke from Siberia greyed the sky.

“Don’t threaten me with leaving filth on my phone,” she mouthed.

“Oh, I can do worse than that,” Lexie said. “What you’ve already seen is enough to get you extradited to England, or even the US.”

“You’d turn me over to the fash?”

“If you were to betray your friend – yes, in a heartbeat.”

A bell rang. Jen slipped into the flow towards class, trying not to shake.

“On the bright side,” Lexie added, “your friend is right. You now have a cheat code to everything. Try me.”

Jen didn’t consult the illicit map again. What she’d seen was enough. She set to work devising an independent, non-nuclear defence policy for a country that was already occupied. She’d joked about taking back Faslane, but the trick would be to scrupulously respect the nuclear enclave and the other bases. They would just have to be by-passed, while everywhere else was secured.

“Wait,” said Sonia, when she looked over Jen’s first draft of a briefing paper. “Is this a plan for territorial defence, or for an uprising?”

“They’re kind of the same thing,” Jen said.

“I see you’ve put our national defence HQ right up against the Faslane perimeter fence.”

“Yup,” said Jen. “Deterrence on the cheap.”

“I like your thinking.” Sonia flicked the paper back to Jen’s phone. “Carry on.”

Morag’s Information policy presumed that the citizen had absolute power over what was on their phones, and that the state had absolute power to break up information monopolies. Jase on Education, and Dani on Health were likewise radical and surprising. Altogether, Sonia’s team got a good grade and a commendation.

Five years later they were still a clique. They met now and then to catch up.

Jen sprinted across Clyde Square, rain rattling her hood, and pushed through swing doors under the sputtering blue neon sign of the Reserve. Mackintosh tribute panels in coloured Perspex sloshed shut behind her. Above the central Nouveau Modern bar, suspended LED lattices sketched phantom chandeliers. Drops glittered as she shook her cape dry. She stuffed it in her shoulder bag, fingered out her phone and stepped to the bar. The gang were around the big corner table. She combined a scan with a wave. Two drinks requests tabbed her glance. She ordered, and took three drinks over.

Skirts and frocks that summer were floral-printed, long and floaty or short and flirty. Jen that evening had dressed for results: black plastic Docs, silver jeans like a chrome finish from ankle to hip, iridescent navy top that quivered as she breathed. Mal couldn’t keep his eyes on her. Jen smiled around and lowered the drinks: East Coast IPA for Mal, G&T for Morag, and an Arran Blonde for herself. Sonia, elegant in long and floaty, sipped green liquid from a bulb through a slender glass coil.

“It’s called Bride of Frankenstein,” she explained. “Absinthe and crème de menthe, mostly.” Jen mimed a shudder.

Sonia’s fair hair was still as long, but wavy now, or perhaps no longer straightened.

“Here tae us,” said Morag, as glasses and bottles clinked. She looked around. “Bit of a step up from the Kettled Copper, eh?”

They all laughed, like the high-school climate-demo veterans they weren’t.

“Coke and five straws, please, miss,” said Mal, in a wheedling voice.

“Oh come on,” said Morag. “We never did coke, even to share.”

“Aye,” said Jase, “we snorted powdered glass and thought ourselves lucky.”

“Powdered glass?” Mal guffawed. “Luxury! In my day—”

“Guys,” Jen broke in, “don’t fucking start that again.”

Jase leaned back, making wiping motions. “It’s dead,” he agreed. He’d lost his plukes but kept his nerdhood. Two pens in his shirt pocket, even on a night out.

“It has ceased to be,” Mal added solemnly.

Jen shot him a warning glance. He looked hard at his pint. Conversation moved on. People changed positions on the long benches. Jen chatted with Mal for a bit, then Dani, then Morag, then Javid. She zoned out, and checked the virtual scene. In her glasses, ghosts moved through the crowd in the Reserve, collecting cash for the Committees. The closest of Greenock’s Committees squatted an empty shop in the mall. Some people flicked money from their phones into virtual plastic buckets; others turned their backs. Jen waved away the phantom youth who approached her, then returned to the real world, where Morag was setting down a bottle in front of her.

“Thanks,” she said, eyeing Morag as she sat down beside her. Morag raised her third G&T. “Cheers.”

“Cheers. So ... how’s the revolution coming along?”

“The revolution?” Morag shook her head, put her glasses on and took them off. “Oh! The Committees? Fucked if I know, hen. I got nothing to do with them.”

“Oh come on.”

“Seriously, Jen. Like a robotics apprenticeship would leave me time for any of that! I mean don’t get me wrong, France is on strike and Germany is on fire, and we all know things can’t go on like this, so good luck to these guys, but what they do is full on and a heavy gig.”

“They have sympathisers.”

Morag shrugged one shoulder. “No doubt. But not me.”

“So what changed?”

“What do you mean?”

“You remember back at school, that SimScot thing?”

“Aye, vaguely. Load a shite. Set me firm for robotics, mind.”

“You slipped me a dodgy app, remember? Called itself Iskander, or Lexie.”

“Oh, aye – you were going on about wanting to research military stuff without leaving tracks, wasn’t that it?” Morag laughed. “We nearly fell out over it.”

“Well, yeah, when I found it was showing me actual military secrets.”

“It did?” Morag’s eyes widened. “All I got was business secrets!”

“There you go,” Jen said. “Anti-capitalist malware.”

“Do you still have it?”

“I suppose so. I could never get rid of it.”

“But you don’t use it?”

“Fuck, no! Anyone who does gets flagged.”

“Ah, right.” Morag sipped her G&T. “You’re in that line now, right?”

“IT security. Yes.”

“Private?”

Jen shrugged. “What is, these days? We get government contracts. Among others.”

“O ... K,” Morag said, voice steady as a gyroscope. “So why are you asking me about something we did when we were kids?”

“Contact tracing,” Jen said. “We know where the app originated. “The European Committee”! Talk about hiding in plain sight! We know how far it’s spread, along with ... well, the attitude that it incites. But when I look back over the records it seems that you and I were, well, pretty much Patient Zero as far as Scotland’s concerned. So the question of where you got it from is exercising some minds, let’s say. And for old times’ sake, Morag, I’d much rather you told me than that you ... had to tell someone else.”

“Like that, is it?”

“I’m sorry, but yeah.”

“Aw right.” Morag put down her glass and spread her hands, palms up, on the table. “Honest to God, Jen, I cannae remember. I was a bad girl.” Her cheek twitched. “Under-age drinking, under-age everything. Guys off cruise ships. Guys on cruise ships. I even went over to—” she jerked her thumb, indicating the other side of the Clyde “—what’s legally England once or twice.”

“Fuck sake, girl.”

“You could say that.”

“So anyway,” said Morag, audibly moving on, “I was damn lucky a dodgy app was the worst I picked up.”

“I’m glad,” Jen said. She grinned at Morag and raised her bottle, then drank. “I am so fucking relieved you’ve cleared that up for me.”

“Cleared it up, maybe,” said Morag, grudgingly, as if not appreciating how nasty a hook she was off. “Can’t say I’ve narrowed it down.”

“Oh, that’s all right. It’ll give my clients something to work on. That’s all they want.”

What Morag had told her was what she would tell them. Jen didn’t care if it was true or not. It got her off the hook, too.

Morag drained her glass. Jen stood up. “Same again?”

“Thanks.”

When she got back Morag was on the other side of the table chatting to Javid, and where Morag had been Sonia was sitting. Jen set down her own drink and looked at Sonia’s mad-scientist apparatus. The green liquid was almost gone.

“Can I—?” Jen ventured.

Head turned, hair tumbling. “Oh, thanks!”

“Another of these?”

“Christ, no!” Sonia laughed. “I wouldn’t dare.” She glanced sideways. “I see you like your Arran Blonde. I’ll try one.”

Jen returned with a second bottle. She hesitated, then plunged.

“Well, here’s to blonde.”

“Here’s to—” Sonia looked puzzled.

Jen laughed. “Polychromatic.”

Sonia was in Education, whatever that meant. She’d studied and now taught at the West of Scotland University. Very much a Head Girl thing, in a way, still. It was odd to see her swigging from a bottle.

“I couldn’t help overhearing what you said to Morag.” Apparently they’d got the catching up out of the way. “You were wrong.”

“About what?”

“It isn’t the Iskander app that’s radicalising kids.”

That sounded like quite a lot of overhearing. “Yeah? So what is it?”

“Apart from—?” Sonia made the helpless gesture, somewhere between a shrug and a wave of the hands, that meant all this. Flowery flutter around her forearms.

“Uh-huh.”

“I’ll tell you a secret.” Sonia shifted closer on the bench, dress whispering. “It’s the Civic and Democratic Engagement programme. The whole idea was – well, you know what it was. It backfired, but Education think that’s because something isn’t quite getting across. The problem is, it is getting across! They’re still doing it, wondering why every year the kids come up with more and more outrageous ideas. They keep tweaking it, but nothing works.”

Jen rocked back. “You mean it’s SimScot?”

“No,” said Sonia. “It isn’t SimScot. It’s just that the whole thing of pushing teenagers to think in terms of practical policies does exactly that. Like the defence policy you came up with. Or Morag’s information policy: the way the problem is posed, any answer has to be revolutionary. This keeps happening.” She let her eyelids drop. “I see what you’re thinking, Jen. Tomorrow you’ll be telling someone to dig into that games company in Dundee.” Sonia’s laugh pealed. “As if!”

It is SimScot, Jen thought. She was certain of it. In the morning she would—

“I’ve done the research,” Sonia said. “Real research, I mean. Peer-reviewed and published. It’s the programme, not the programme, ha-ha!”

“Have you told Education?”

“Of course I’ve told them. They know. They listen. They take my findings seriously. And they keep doing the same thing!” She thumped the table. “And that! Is! The Entire! Fucking! Problem!”

People were looking.

“Sorry,” said Sonia. Her voice lowered. “Bit squiffy.”

“Blame the Bride of Frankenstein.”

“Better have some more Arran Blonde, in that case.” Sonia swigged. “Another?”

They had another. It didn’t help.

“Take me home,” Sonia said.

Sonia lived in a high flat, looking east from Greenock. As the room brightened, Jen sat sharply up from a sleepy huddle.

“What is it?” Sonia mumbled, into the pillow.

“Something just dawned on me.”

“Oh, very good,” Sonia chuckled. “What?”

Jen gazed down at the cascade of yellow hair.

“It’s you,” she said. “It was always you. It was you all along.”

“Aw,” Sonia said. “That’s so nice.” The skin over her shoulder blade moved. Her hand brushed Jen’s hip, then slipped off.

“No,” said Jen. “That isn’t what I—”

But Sonia had already gone back to sleep.

Jen waited for Sonia’s breathing to become even, then rolled out of bed and padded over to the window. The wind had shifted, pushing the overnight rain back to the Atlantic. Smoke from forest fires in Germany hazed the rising sun. The sky above Port Glasgow was the colour of a hotplate, turned to a high level.

Ken MacLeod lives in Gourock on the west coast of Scotland. He has degrees in biological sciences, worked in IT, and is now a full-time writer. He is the author of eighteen novels, from The Star Fraction (1995) to Beyond the Hallowed Sky (2021), and many articles and short stories.

Art: Simon Walpole

The Shadow Ministers is set about thirty years before Beyond the Hallowed Sky, in the months leading up to the events remembered in that book (and its sequels in the Lightspeed Trilogy) as the Rising. We may suspect that Morag in the story will become Morag in the novel, but her records have been deleted under the Act of Indemnity.