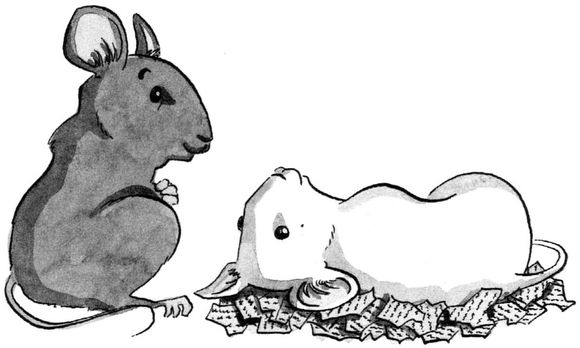

John Robinson and Mr. Brown were next-door neighbors. That is to say, they both lived under the kitchen floor, for John Robinson and Mr. Brown were house mice.

John was a young chap. He was respectful toward his neighbor, who was very old, and always addressed him as “Mr. Brown.” Mr. Brown, John knew, now lived alone because his wife had been eaten by the cat.

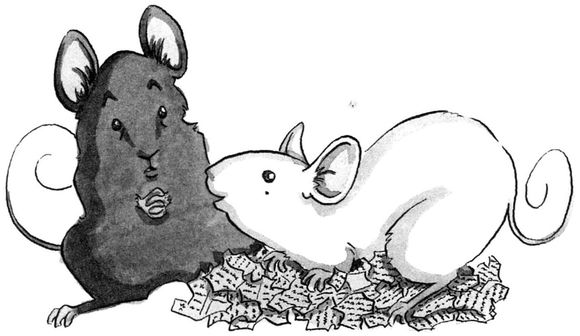

There came an evening when John’s young wife, Janet, told him that he was to become a father for the first time. She was tearing up bits of newspaper to make a comfy nest.

“Gosh!” said John.

“You mean you’re going to have a baby?”

“Babies,” said Janet.

She has gotten fat lately, come to think of it, said John to himself.

“When?” he asked.

“Very soon.”

“Gosh! How many?”

“How do I know, you stupid mouse?” said Janet. “Now push off and leave me in peace.”

As John was hurrying under the kitchen floor, he met his neighbor coming back home.

“Good evening, Mr. Brown,” he said.

“Evening, John,” said Mr. Brown. “How’s life?”

“Wonderful!” replied John. “I am going to be a father.”

“For the first time, eh?”

“Yes. I believe you’ve had a large number of children, Mr. Brown, haven’t you?”

“Dozens. So many that I’ve gone and forgotten most of their names. My late wife and I used to rely on the alphabet.”

“The alphabet?” said John.

“Yes. Start with A—Adam, let’s say, or Alice—and keep going till you get to Z. That gives you twenty-six names.”

“You mean you’ve had twenty-six children, Mr. Brown?”

“Seventy-eight, actually, John. We went through the alphabet three times.”

“Gosh!” said John.

“Xs and Zs,” said Mr. Brown, “are the hardest

ones to put names to, but we managed. Why don’t you try the same trick?”

“I will, I will,” said John. “Thanks, Mr. Brown, that’s a good idea.”

The young mouse and his elderly neighbor chatted for a while, mainly about food. A nest under the kitchen floor, as both knew well, is the best place for mice to live. Those clumsy giants called humans were always dropping bits of food on the floor, and if a mouse was bold enough, there were lovely things to eat in the pantry.

Talking about food made John feel hungry, and after a while he said, “I must be going, Mr. Brown, if you’ll excuse me.”

“Of course, John,” Mr. Brown replied, “and I’m so pleased to hear your good news. Please give my regards to your wife.”

“I will,” replied John, “and thank you.”

Poor old fellow, he thought, remembering what had happened to Mrs. Brown.

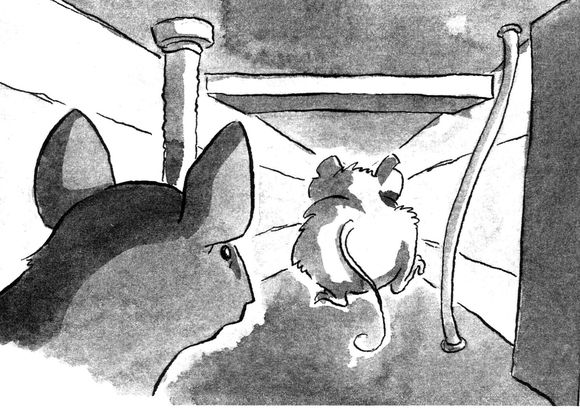

Now evening had turned to night, and the giants had all gone up the stairs to bed. John Robinson popped out of a mousehole and began

to search the kitchen floor, all his senses alert, especially for the squeak of the cat flap.

He was in luck. Someone had spilled half a dozen cornflakes: not much for a giant, but a feast for a mouse.

His hunger satisfied, he made his way home.

Will Janet have had the babies yet? he wondered.

How many will there be? How many will be boys; how many girls?

The answers to these questions, John found, were “yes,” “six,” and “three of each.”

“What should we call them?” John asked.

“You can choose, if you want,” said Janet.

I’ll use Mr. Brown’s alphabet method, thought John. Six kids, that’s A to F. Let’s see now … I must think up some unusual names because I’m sure my children will grow up to be unusual mice.

John Robinson spent the rest of the night

deciding what to call his newborn sons and daughters. As dawn broke, he knew he had found six perfect names. And, he said to himself, I must tell Mr. Brown. I’m sure he’d like to know, and he hurried along one of the runways beneath the kitchen floor.

“Mr. Brown,” he said, when he had found his neighbor, “Janet’s had six babies. I thought you’d like to know.”

“Congratulations, John!” said Mr. Brown. “Got names for them?”

“I have,” said John. “Ambrose, Beaumont, Camilla, Desdemona, Eustace, and Felicity What d’you think?”

“Brilliant!” said Mr. Brown. “Three boys and three girls, eh? It’s a start. Twenty more babies and you’ll have finished your first alphabet of names.”

Gosh! said John to himself. To think that his neighbor had seventy-eight kids!

Even as he thought this, they heard, through the floorboards above their heads, the squeak of the cat flap.