“Emigrate?” said John to Beaumont.

“Yes, Dad.”

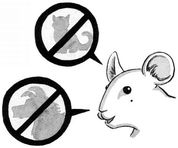

“But … how will I know if another house has a cat or not?”

“If it has a cat, it’ll smell of the beastly thing. If it doesn’t, it won’t. Simple, Dad.”

“It’ll take me an awfully long time to inspect every house on the street.”

“It would if it was just you, Dad,” said Beaumont, “but what if we all helped, eh, Mom?”

“I certainly will,” said Janet, “but you kids are too small to take the risk.”

“We’re not,” said Beaumont, turning to the other five mousekins, “are we? We can help, can’t we?”

And with one voice, Ambrose and Camilla and Desdemona and Eustace and Felicity cried, “Yes!”

Janet looked proudly at her six children.

“All right,” she said, “but not just yet. Wait till you’ve grown a lot bigger.”

“And a lot faster on your feet,” added John. “There’ll be other cats in other houses on the street, and dogs, too, and then there’s all the traffic. Wait till you’re as big as Mom and me.”

“But that’ll be ages, Dad!” said Beaumont.

“Do as your father says,” said Janet sharply, and in unison, Ambrose and Beaumont and Camilla and Desdemona and Eustace and Felicity muttered, “Yes, Mom.”

In fact, a month went by before John and Janet allowed the six mousekins out of the house.

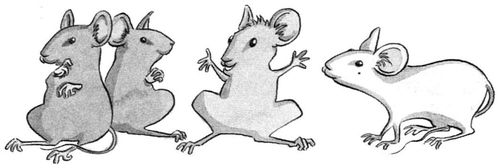

John had established a route—from under the kitchen floor through a runway that led down into the cellar, and from the cellar up and out through a grating onto the sidewalk outside.

Janet made a plan of action. Their house was number 24, even-numbered like all those on that

side of the street. Each night she and the three girls would work their way down the road, somehow making their way into number 22, then number 20, and so on, while John and the three boys would be inspecting each house up the street—numbers 26, 28, 30, and so on.

“Let’s just hope they don’t all have cats in them, Janet,” said John. “I don’t fancy having to cross the road.”

But luck was on their side.

On the fourth night, Janet and the girls explored number 16 and came home excited and delighted to report that there was no smell or sign of cat or dog in that house.

“All we could smell,” said Janet, “was mice

“Great!” said John. “We’ll emigrate there.”

Five of the mousekins squeaked with joy, but Beaumont said, “What about Uncle Brown?”

“What about him?” said the others.

“He’ll be lonely without us.”

“Beaumont’s right,” said Janet. “He might like to come too, don’t you think, John? Why don’t you ask him?”

Of course we must, thought John. He saved Beaumont’s life.

So one of the girls—Felicity, it was—was sent to fetch Mr. Brown.

“We’re moving, Mr. Brown,” said John when

the old mouse arrived. “To get away from the cat.”

Just what I was thinking, said Mr. Brown to himself.

“We’re going to number 16; there’s no cat there,” said John.

“We wondered if you’d like to come with us,” said Janet.

“It’s very kind of you, Mrs. Robinson—”

“‘Janet,’ please,” she interrupted.

“—very kind of you, er, Janet, as I was saying, but I’m sure you’d rather be on your own as a family. I’ll miss you, of course.”

“No, you won’t, Mr. Brown,” said John in a masterful voice. “I insist that you come with us. Please do.”

“We can’t go without you, Uncle Brown,” said Beaumont quietly.

Uncle, thought the old mouse. How nice. Some of my seventy-eight children must, I hope, be alive and well, but I never see any of them. They’ve all gone off somewhere, so why don’t I run off too?

“Please come, Uncle Brown!” squeaked the other mousekins.

“Pleeeease!”

And then they heard the sound of the cat flap

as the cat, attracted by all the noise, came into the kitchen.

Mr. Brown looked at Janet and John and at Beaumont and the five other youngsters.

“Thank you,” he said. “I’d love to.”