Women in general take less risk than men. It is a fact that can be drawn from a multitude of experiments spread over a wide range of scenarios. Some psychologists feel that it represents a difference in the perception of problems: where women see risk, men see challenge! Others advance a biological thesis: because women have had a greater responsibility than men in the reproductive process, they are preconditioned by evolution to be less desirous of taking risks than are men. Whatever the case, financial decisions do not seem to be an exception to the rule. When it comes to investing, women show more prudence than men.

One way of experimentally evaluating the risk aversion of individuals is to provide them with capital and give them carte blanche to invest a portion of it in a risky instrument which offers the hope of a positive gain. The larger the fraction of the capital an individual invests in this instrument, the less he is hostile to risk. This is the method selected by Gneezy, Thaler, and Yu (2004).1 They sought out students for an experiment on the Internet and in the laboratory which consisted in successively betting over 15 periods a constantly renewed capital of $100. In each period, the subjects had the choice of keeping the capital intact or investing a fraction (of their choice) in a risky asset which could multiply their investment by 3.5 with a probability of one third or lose it totally with a probability of two thirds. As the average gain on such an investment is positive, an individual who is not averse to risk would invest all his money and would be able to maximize his wealth at the end of the experiment. An individual averse to risk invests less in the asset in proportion to the strength of the aversion. Comparing the investments of the male and female students, the experimenters were able to conclude without hesitation that women are more averse to risk than are men. All in all, the men invested a fraction of their capital that was 50 percent higher than that of the women.

Higher risk aversion among women is without doubt the most plausible explanation for some behavioral differences found by the economists. Although women live longer than men, they participate less in company retirement savings plans. This goes against the predictions of a life cycle model in which people save with the goal of spreading their consumption over their entire lives. Since women are retired for a longer time period than men, they should save more during their active years. Empirical studies clearly illustrate the contrary. This paradox dissolves if it turns out that women consider suggested investments in retirement savings plans as too risky for them. It is possible that they make up their smaller contributions to these plans by greater savings outside of them, for example in assured return instruments. However, in either case, they lose an important source of income because such products offer a return considerably less than other funds invested in stocks and bonds, which are recommended through these plans. Moreover, they do not allow profiting from other advantages such as contributions by the employer. Fortunately, for women who intend to retire (and for the theory which never does), the difference in the rates of contribution between men and women seems to have largely diminished, even reversed, over the past few years.

Because of their greater risk aversion, when women invest, they tend to choose less risky investments than do men in the same income and wealth categories. Therefore they have a greater tendency than men to favor cash investments and bonds to the detriment of stocks.

Bernasek and Shwiff (2001)2 sent a detailed questionnaire to professors of several universities in Colorado to understand their behavior with respect to retirement savings plans. The document contained many questions on the economic and social situation of the respondents, their level of education, and the makeup of their households, in such a manner that allowed the authors to evaluate precisely the impact of each variable independently of the others on the proportion of stocks held in retirement savings plans of the professors. The gender of the respondent was one of the few variables which had a significant influence on this proportion. All things being equal otherwise, women invest 12 percent less in stocks in their retirement plans than do men.

It should be noted that men and women also show a difference in attitude relative to the risk that their partner is ready to take. The fact of having a partner only slightly averse to risk increases the part of a plan allocated to stocks for a man and reduces it for a woman! Women look to compensate for the “risk all” view of their partner by investing in a more prudent manner than had they been alone. Other studies (Sunden and Surette, 1998)3 confirm this subtle point regarding the financial relations within the couple.

If all humans are subject to overconfidence, men are more so than women. One of the psychological motivations generally used to explain this difference is the less prominent display of the self-attribution bias by women. Unlike men, they do not think that their past successes substantiate the hypothesis that they are highly gifted.

Various studies show that the difference in confidence is especially obvious for masculine activities. Given the overrepresentation of men in the world of finance, it is not surprising that they are thought to be more competent than women in financial matters. With respect to stock investing, it has been said that men spend more time and money in the personal analysis of stocks, seek the assistance of their advisors less, are more active, think that returns are more easily predictable, and expect better performances of their portfolios. Surveys show that if both men and women feel that they are going to beat the market, the men expect even higher extra returns.

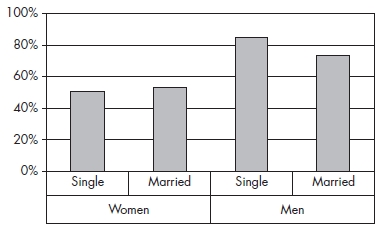

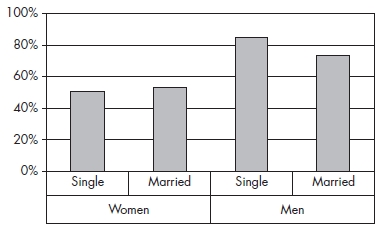

Barber and Odean (2001)4 have scrutinized a data base consisting of 37,664 securities accounts for which they have been able to identify the gender of the person who has opened the account. Their principal objective was to validate or quash the notion that, consistent with the idea that men display more overconfidence than women, male investors bought and sold more often and, as a result, show performances lower than those of women. They, indeed, found that men have turnover 45 percent higher than that of women, which results in their posting an annual return of 2.65 points less than the market as opposed to −1.72 points for the women. If only single persons are considered, the turnover is 67 percent higher for men with an annual return 2.3 points lower relative to women (see Figure 6.1).

Barber and Odean also noted that the men in their sample were taking more risky positions, investing in securities which display a higher beta (that is which amplify market movements), more strongly volatile, and of small companies. Single men have even more overconfidence than married men. On the other hand, single women are the most prudent. Perhaps because within couples, men and women talk to and influence one another, natural differences are ironed out. Or, perhaps, the most overconfident men and the least confident women never find someone to marry.

Figure 6.1 Annual turnover in portfolios

Source: Barber and Odean (2001).

Natural differences with respect to risk nevertheless seem to fade with experience and knowledge of financial markets. In a laboratory experiment seeking to assess lotteries, Gysler, Kruse, and Schubert (2002)5 find, for example, that for women, and not men, risk aversion decreases as expertise increases.

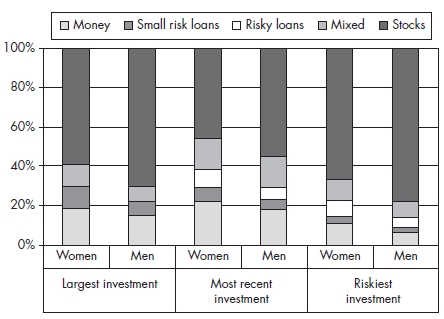

Dwyer, Gilkeson, and List (2002)6 looked to see if choices in investments of men and women converged as they acquired solid experience in the markets (see Figure 6.2). To this purpose, they studied the accounts of 2,000 investors in mutual funds and noted carefully the funds that, for these investors, constituted the largest investment, the most recent, and the riskiest. They classified the different funds bought by these investors into five categories from the least risky to the riskiest: money markets, small risk bonds, risky bonds, mixed, and solely stocks. The data categorized according to the gender of the investor shows that the women opted for less risky funds than the men, whatever indicator was used (the largest investment, the most recent, or the riskiest). For example, only 59 percent of the women, compared to 70 percent for the men, had the purchase of stock funds as their largest investment. Moreover, 11 percent of women had money market funds as their riskiest investment compared to 65 percent for the men.

Figure 6.2 Male and female investment choices

Source: Dwyer, Gilkeson, and List (2002).

The statistical treatment of the data shows, however, that the difference diminishes when the level of financial knowledge of the individuals is taken into account. The men were on average more educated in these matters than the women. The financial knowledge was measured from the answers to 12 questions: six definite questions on the financial markets and six questions which required the respondent to provide a self-assessed measure of their comprehension of some very specific financial terms. When the financial knowledge was not controlled, the men had a probability 8.3 points higher than the women of having their largest investment in stock funds. When the financial knowledge was controlled, this probability difference fell to five points, that is 40 percent less. These results take account of differences in age, education, and income among the investors.

Acknowledgment that gender differences in behavior in the face of risk disappear with knowledge of financial markets finds an interesting echo among professional fund managers. For this experienced population, the work of Atkinson, Baird, and Frye (2003)7 finds no significant difference between men and women in matters of performance, level of risk, spending, and turnover. According to the authors, the results mean that the differences obtained for individual investors are not due to gender differences but rather to differences in market experience and in wealth. The principal difference that they find relates in fact to investors in funds. For comparable performances and experience, the flow is smaller toward funds managed by women than those managed by men, especially for unproven managers. The authors explain this distinction by sexist stereotypes which maintain that women are less competent than men in financial matters.

Endnotes

1 Gneezy, U., R. Thaler, and F. Yu, “Information Availability and Investment Behavior” (mimeo, University of Chicago, 2004); and Balkin, D., “Gender Effects on Employee Participation and Investment Behavior with 401(k) Retirement Plans” (mimeo, University of Colorado, 2000).

2 Bernasek, A., and S. Shwiff, “Gender, Risk, and Retirement,” Journal of Economic Issues, 2, (2001): 345–356.

3 Sunden, A., and B. Surette, “Gender Differences in the Allocation of Assets in Retirement Savings Plans,” American Economic Review, Papers and Proceedings, 88, (1998): 207–211.

4 Barber, B., and T. Odean, “Boys will be Boys: Gender, Overconfidence and Common Stock Investment,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 116, (2001): 261–292; and Lewellen, W., R. Lease, and G. Schlarbaum, “Patterns of Investment Strategy and Behavior Among Individual Investors,” Journal of Business, 50(3), (1977): 296–333; M. Prince, “Women, Men, and Money Styles,” Journal of Economic Psychology, 14 (1), (1993): 175–183.

5 Gysler, M., J. Kruse, and R. Shubert, “Ambiguity and Gender Differences in Financial Decision Making: An Experimental Examination of Competence and Confidence Effects” (working paper, Center for Economic Research, Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, 2002).

6 Dwyer, P., J. Gilkeson, and J. List, “Gender Differences in Revealed Risk Taking: Evidence from Mutual Fund Investors,” Economics Letters, 76, (2002): 151–158.

7 Atkinson, S., S. Baird, and M. Frye, “Do Female Mutual Fund Managers Manage Differently?” Journal of Financial Research, 26 (1), (2003): 1–19.