In general, the necessity of diversifying the portfolio is acknowledged by investors. Once accepted though, the principle still remains to be applied. And there’s the rub. Researchers have noticed that investors practice a diversification that is far from optimal according to financial theory. While the theory recommends to spread funds over different instruments whose performances are largely independent of one another, investors are content to distribute their money over the financial products which are available, without caring about correlations in their performances. For the academics, the diversification which is put in place is “naïve diversification.” A mechanism largely spread among investors is that of the heuristic “1/n” which consists in distributing money equally over the n products which are directly proposed to them. Never mind that the products are very similar or very different.

The heuristic 1/n was first brought to light through consumer choices. Researchers in marketing showed that people had a tendency to apply a naïve diversification when faced with simultaneous choices and no diversification when they had to make sequential choices. This discovery leads one to think that in portfolio choices, the investor can have different behaviors at the initial assembling of the portfolio and during subsequent adjustments. At first he is tempted to distribute his funds equally among various available instruments and to strengthen himself later in those which he trusts the most. This intuitive strategy, however, presents a great risk of imbalance of the portfolio because little by little the weight of one of the securities increases with respect to the others.

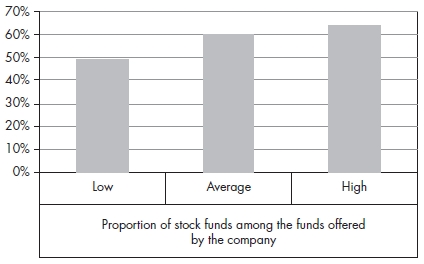

As an illustration of the heuristic 1/n at work in the assembling of portfolios, Benartzi and Thaler (2001)1 compare the contributions to their company retirement savings plans by the pilots of the airline TWA and by employees of the University of California. These two examples constitute textbook cases because five stock funds and only one bond fund were proposed to the pilots, while the UC employees had the choice among only one stock fund and four bond funds. As predicted, the two populations opted for very different distributions which were very far from the national average. The pilots on average invested 75 percent of their contributions in stocks and the employees of the University of California only 34 percent. The average American salaried employee invests 57 percent of his contributions in stocks. With a database of 170 retirement saving plans subscribed to by 1.56 million American employees, the two authors generalized the above results showing that the allocation of securities decided by the investors is directly related to the funds offered to them. The authors classified the 170 plans into three sub-categories: those which offer a large proportion of stock funds, those which offer an average proportion, and those which offer a low proportion. They then compared the median proportion of stock funds in the offerings of the plans in each sub-category and the proportion allocated to stocks by the employees. The results show a very strong correlation between the two variables. The three sub-categories proposed 81 percent, 65 percent, and 37 percent in stock funds and the employees subject to these proposals invested 64 percent, 60 percent, and 49 percent, respectively, of their contributions in stocks (see Figure 10.1).

Figure 10.1 Proportion of stocks in the employee’s portfolio

The observed differences are too significant to be explained by possible differences of attitudes between employees relative to risk or by the legitimate need for diversification of the portfolio between different funds within the same class of securities. The offering made to employees greatly influences their choices because they have recourse to a simple rule for making a decision. A simple rule, yes, but not an optimal one.

When the situation calls for the making of a decision and the criteria for choice suggest contradictory results, people often select the median solution which has the advantage of limiting the risk for error. Suppose that you are undecided between two cameras distinguishable by their technical features and their price: one sophisticated and expensive and the other simpler and cheaper. If a third camera, clearly more expensive and more sophisticated, is proffered then it is probable that, in the end, you will buy the middle camera, previously the more sophisticated. The introduction of the new camera has not changed your preferences but has modified the profile of risk (regret) associated with each option. Logically, in the middle of the range, the risk is less elevated.

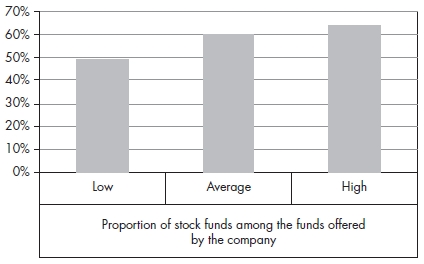

Benartzi and Thaler (2002)2 sought to verify whether preferences of individuals regarding the portfolio were indifferent to the context or if they showed a marked aversion to extremes. They asked some students at the University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA) to rank some portfolios distinguishable only by their expected returns in two market configurations (a good circumstance and a bad one) which could occur with the same probability, namely a one in two chance. The were four portfolios used (see Table 10.1).

The subjects were randomly placed in an experimental situation from among three possibilities: 1) the portfolios are arranged in order of preference A, B, and C; 2) only the portfolios B and C; and finally, 3) the portfolios B, C, and D. If the context (the place in the range) is without importance in the subjects’ choices, then the proportion of subjects preferring C to B should be the same in all three situations. Indeed, if the subjects have a sole order of preferences, then the availability of A or D will not change the relation of preference between B and C. The results of the experiment clearly show the contrary. The proportion of subjects preferring C to B is 54 percent for the choice BCD (when C is the median option), 39 percent for the choice BC, and 29 percent for the choice ABC (when B is the median).

Table 10.1 Four portfolio choices

The observed differences are statistically significant and suggest that the median position of a choice greatly increases its attractiveness or conversely that an extreme position diminishes it. The conclusion is that investors have very flexible “risk preferences.” By proposing more risky funds to them, one can move their preferences and their choices of portfolio toward a greater tolerance for risk. On the other hand, by increasing the range of offerings with low risk funds, one increases de facto the aversion of investors to risk.

A multitude of experiments, conducted particularly in marketing, report the presence of a sensation of stress at the time of making a choice. The decision is seen as a solemn moment and particularly crucial when the individual wishes above all not to make a mistake in order to avoid having regret afterward. When an individual faces a battery of choices, he has a tendency to delay the decision hoping that time will help him see things more clearly. Researchers have noticed that the indecision becomes all the greater as the number of competing options grows. For example, Iyengar and Lepper (2000)3 showed through an amusing experiment inside an upscale grocery store that an extensive choice can hinder the decision to buy. The two experimenters set up a booth in the middle of the store from which they offered jams of different flavors to passing customers. They tested two experimental situations, one with 24 flavors and the other with six flavors. As could have been predicted, the passersby stopped more often when the booth displayed 24 flavors (60 percent of the passersby) than when it had four times less (40 percent). On the other hand, the customers who stopped bought much less from the booth with a wide choice (3 percent) than from the booth with a limited choice (30 percent). At the end of the day, it is therefore the smaller booth which will have realized the better sales.

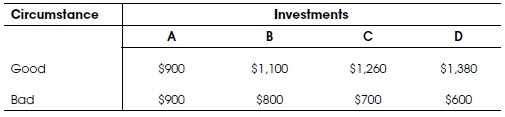

Iyengar and Jiang (2005)4 wanted to verify that the results found for purchase decisions applied equally well to investment decisions. They studied the contributions of 800,000 American salaried employees to 643 retirement savings plans as a function of the number of funds offered within these plans. In order to see whether the number of alternatives truly had an effect on the rate of participation of the employees, they made a number of regressions including multiple controls on the characteristics of the plans, the companies, and the employees. Their conclusion is that indeed the employees are less inclined to participate in the plans that are composed of a large number of funds (money market, bonds, stocks, or mixed). On average, each time 10 new choices are added, the rate of participation falls by 2 percent. The decline is the most noticeable at the passage from 2 to 12 funds (the participation falls from 75 percent to 69 percent) and from 30 to 40 funds (from 72 percent to 66 percent; see Figure 10.2).

The results presented here are due to the fact that, contrary to what the economic theory believes, the individual unquestionably does not make his choices by comparing the different options to his preferences, which are perfectly known, and then selecting what is most “compatible.” The process followed consists more in comparing the attributes of the various alternatives and choosing the best according to several pertinent criteria. When the number of alternatives is high, this comparison becomes impossible and the choice is postponed, possibly indefinitely.

Figure 10.2 Participation in retirement savings plans vs. number of funds offered

Source: Iyengar and Jiang (2005).

Faced with a difficult decision to make, it is just as tempting to do nothing. Rather than make a mistake, it is preferred, like it or not, to take this default option. If a posteriori this choice turns out not to have been the best, at least one cannot blame oneself for having caused one’s own loss by changing the course of events. Experiments have validated that view in showing that, in relation to inaction, action increases the joy drawn from a favorable event but also the displeasure associated with an unhappy result. Those who fear losses above all will have a tendency to do nothing. This tendency, denoted the omission bias, reminds us of several points about the status quo bias discussed in experiment 30. The two are often inseparable because often doing nothing leads to preserving the status quo. Nevertheless, several experiments have been able to distinguish between the two biases and show that inertia in decisions cannot be reduced to the single desire to maintain a situation unchanged.

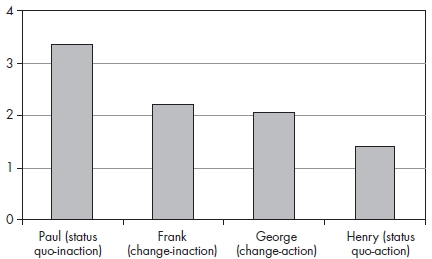

Ritov and Baron (1992)5 designed an experiment to distinguish the importance of the omission bias and the status quo bias in decisions. They asked 20 students to rank four imaginary persons, Paul, George, Frank, and Henry according their degree of happiness. The four people are all in the same situation of presently holding in their portfolio stocks of company A, although they could have had stocks of company B which would have made them $1,200 richer. The difference between the four people relates to the scenario which they experienced:

The results show that the subjects felt that the scenario had had a great influence on the degree of happiness of the four persons. It is Paul, who did nothing and thereby maintained the status quo, who, by far, is the least unhappy at the end of the year. George and Henry, who have been active, are, in the end, the unhappiest. The experiment has been reproduced with other types of choices and the same results were found. Each time when the outcome is unfortunate, action seems to affect happiness more than inaction (see Figure 10.3).

Such a result suggests that investors are sensitive to the alternatives which are presented to them. A choice by default will have a greater chance of being “selected” than a choice which requires a personal action and involvement.

Madrian and Shea (2001)6 confirmed this idea showing that automatic enrollment of employees in a retirement savings plan of their company (a large American corporation) considerably modified the behavior of the employees with respect to the plan. The authors identified two populations: employees newly hired by the company who were automatically enrolled in the plan (at least without having requested the contrary) and the veteran employees for whom enrollment required a personal application. They saw enormous differences between the two populations regarding the level of participation, the level of average contributions, and the allocation of funds among the different securities offered. Of the new employees 86 percent joined the plan as opposed to 37 percent of the veteran employees. As well, 76 percent of the former invested 3 percent of their salary each month, the default contribution, against only 12 percent of the veteran employees (who did however make larger contributions). Finally, the new employees invested 80 percent of their savings in the money market, which again is the fund for the default option, and only 16 percent in stocks, while the veteran employees, without access to the default option, made a much riskier allocation, 8 percent and 73 percent, respectively.

Figure 10.3 Happiness (average ranking)

Laziness, the inability to decide, and the fear that the decision made will be bad are some of the factors which cause default options to recruit more adherents than do the alternatives. They leave a role and a (too?) important responsibility to the company in the setting of levels of contributions and of allocation of reserved savings in employment savings or retirement plans.

Anchoring explains the tendency to focus on a number and to use it as a benchmark when making a valuation. Surprisingly, the anchoring bias operates even in the absence of a logical connection between the benchmark number and the valuation to perform! For example, some psychology researchers played at “messing up” processes of dating historical events starting with random numbers… that the subjects knew were random! Thus, Russo and Schoemaker (1989)7 asked 500 MBA students in what year was Attila beaten by the Romans and the Visigoths. To confuse their answers, he asked the students themselves to generate a number by adding 400 to the last three digits of their telephone number. The number thus produced, lying between 400 and 1,399, obviously bore no relation to the question asked. However, the answers were very clearly affected by the dummy number. On average the students answered 629 when the dummy number was between 400 and 599 and 988 when it was between 1,200 and 1,399! The correct answer is 451. Another classic example is given by the experiment led by Tversky and Kahneman (1974).8 After having turned a wheel numbered from 0 to 100, subjects had to estimate the number of African countries that are members of the UN. It turned out the number given by the wheel, obviously a random one, greatly influenced the guesses of those surveyed. The first group, who spun a median number of 10, had a median guess of 25, while a second group, with a median spin of 65, gave a median response of 45. These results concur with each other and show that our guesses are never independent of the context. We are influenced by the posted price, no matter how harebrained (as in the souks) or just exaggerated. From the first experiments performed between 1960 and 1970, numerous studies have confirmed the existence of this bias, even for extreme anchors. They indicate that individuals form their estimate from an initial value and then proceed to make an adjustment which is invariably too small. The reason for this under correction is a subject of discussion. One possibility is that the individual stops the adjustment procedure as soon as it provides a plausible value.

In the markets, financial or otherwise, a plethora of numbers can be thought of as anchors for the participants. We have already shown in the experiment on the momentum bias (experiment 1) that past performances influence the prediction of future performance. The posted price can anchor the price targets for investors. Study of the forecasts of individual investors given on financial information Web sites suggests, for example, that they often determine their price targets by adding a fixed premium to the listed price.

Anchorage of the posted price has been tested by an experiment performed on real estate market professionals. Northcraft and Neale (1987)9 asked some real estate agents to evaluate a house that they were able to visit and for which they had a brochure at their disposal which contained several details including the price asked by the owners. They divided their sample of agents in two; one group had access to a brochure stating that the owners were asking $65,900 for their property, the other group had the same brochure but it said that the asking price was $83,900. For the first group, whose specified price in the brochure was $65,900, the average valuation was $67,811. For the second group, whose benchmark price was higher, the average valuation rose to $75,190, that is, 12 percent more, even though the same property and certified professionals were involved.

The owner who is selling his house has then a strong interest in asking a price much higher than he hopes to get. By proceeding in this manner, he can bias the valuation by the real estate agent and, more importantly, that of potential buyers. The latter would certainly think that the price is a bit inflated but at the time of making a counteroffer, they would tend to ask for too small a reduction, especially if they have a fuzzy sense of market prices.

Because investors in general present a strong risk aversion, especially to risk of loss, the frequency of viewing the performance of investments takes on a predominant importance in their choices. When an investment presents both elevated (historic) return and risk, the probability that its performance is negative over some period is even higher when the period is short. The more the period is extended, the nearer is the average posted return to the historic return. Extreme returns, very high or very low, become less and less probable. The scenario is the same as when playing a game of heads or tails: the probability that tossing tails causes you to lose three times in a row (one chance in eight) is much higher than the probability of losing 300 times in a row! On 300 tosses you can almost be sure, by methodically playing tails, of winning about 150 times, that is, once in two tries. In the same way, on the stock exchange, by betting over long periods, the investor grabs the historic return (of the order of 6 percent to 8 percent net) and has an almost zero chance of realizing a negative performance. On the other hand, over very short periods, the risk of losing money becomes very high. Stocks are much more attractive for the investor hostile to loss when their return is looked at over a long period.

Thaler, et al (1997)10 studied the impact of the frequency of observations of returns on investors’ portfolio decisions. They called upon 80 students of the University of California at Berkeley and put them into the role of managers of a portfolio of a small university that must choose between two funds A and B for which they know neither the source nor the characteristics of the return. The students had to indicate on several successive occasions the proportion of the portfolio they decided to invest in the two funds. This was done as a function of the information they received on past performances. The students were divided into three groups distinguished by the lengths of the periods of investment with which they were confronted. The group subject to the “monthly” treatment had to give 200 investment decisions corresponding to 200 periods and after each decision received the return observed over that period. In the “annual” treatment, the students had to deliver 25 allocations, each taking effect over eight successive periods and received after each decision the total return over the eight periods concerned. Finally, in the “long-term” treatment, the students decided and obtained returns over blocks of 40 consecutive periods. The three groups moreover had to produce a final decision for the allocation, valid for the 400 periods following the end of the first investment period. The results attest that the allocation of securities between the two funds over the final years of investment is much more in favor of fund A, the less risky, when the decisions and the return on the decision is monthly than when it is annually or long-term. In the first treatment the students allocated about 60 percent of their portfolio to this fund while in the two other cases they allocated only 30 percent to it. A detail which is perhaps not without significance, is that the returns chosen for funds A and B had been drawn from the distributions of returns of American five-year bonds and American stocks, respectively.

Benartzi and Thaler (1995)11 show that the enormous spread in return, a puzzle in the eyes of financial theory, between stocks on one hand and bonds and the money market on the other, can be explained by what they call “myopic loss aversion” of investors. This is an aversion to losses combined with an overly frequent assessment of performances of the investments. Specifically, the premium of stocks would cause investors to revise their portfolios every 13 months, a figure which seems quite plausible. With loss aversion taken into account, a revision more often would make stocks less attractive and would increase their risk premium even more. Conversely, the “smoothing” of the stock performances over longer periods would cause them to invest more in stocks and would reduce the subsequent spread of return between stocks and bonds.

These results invite the investor to follow the performance of his portfolio less actively in order to not get frightened during bearish episodes. By voluntarily blindfolding himself, the investor can more easily invest in stocks and can profit from their “abnormally” high return.

Endnotes

1 Benartzi, S., and R. Thaler, “Naive Diversification Strategies in Retirement Savings Plans,” American Economic Review, 91, (2001): 79–98; Read, D., and G. Loewenstein, “Diversification Bias: Explaining the Discrepancy in Variety Seeking between Combined and Separated Choices,” Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 1, (1995): 34–49; and Simonson, I., “The Effect of Purchase Quantity and Timing on Variety–Seeking Behavior,” Journal of Marketing Research, 27 (2), (1990): 150–163.

2 Benartzi, S., and R. Thaler, “How Much is Investor Autonomy Worth?” Journal of Finance, 17 (4), (2002): 1,593–1,616.

3 Iyengar, S., and M. Lepper, “When Choice is Demotivating: Can One Desire too Much of a Good Thing?” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79, (2000): 995–1,006.

4 Iyengar, S., and W. Jiang, “The Psychological Costs of Ever Increasing Choice: A Fallback to the Sure Bet” (working paper, Columbia University, 2005).

5 Ritov, I., and J. Baron, “Status-Quo and Omission Biases,” Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 5, (1992): 49–61.

6 Madrian, B., and D. Shea, “The Power of Suggestion: Inertia in 401(k) Participation and Savings Behavior,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 116 (4), (2001): 1,149–1,188.

7 Russo, J., and P. Schoemaker, Decision Traps (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1989).

8 Tversky, A., and D. Kahneman, “Judgment under Uncertainty Heuristics and Biases,” Science, 185, (1974):1,124–1,130.

9 Northcraft, G., and M. Neale, “Expert, Amateurs, and Real Estate: An Anchoring-and-Adjustment Perspective on Property Pricing Decisions,” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 39, (1987): 228–241.

10 Thaler, R., A. Tversky, D. Kahneman, and A. Schwartz, “The Effect of Myopia and Loss Aversion on Risk Taking: An Experimental Test,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, May, (1997): 647–662.

11 Benartzi, S., and R. Thaler, “Myopic Loss Aversion and the Equity Premium Puzzle,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 110 (1), (1995): 73–92.