1.2. The Fourfold

Once we begin to talk about the features and capacities of objects as distinct from the objects themselves, we stumble upon the second fundamental axis around which Harman’s system turns: the distinction between objects and their qualities. Things are not just torn between their subterranean execution and its phenomenal effects, but also between their persistent unity and its constituent plurality. This does not concern how a singular whole is composed of multiple parts (e.g., the composition of an ice cube out of molecules), although this is a related issue, but how a single entity is determined in various ways (e.g., the coldness, hardness, or translucency of the ice cube). The mutual withdrawal between parts and whole noted above consists in wholes having qualities their parts lack (e.g., the molecules are neither translucent nor hard), and parts having qualities their wholes ignore (e.g., the unique chemical properties of the trace amount of minerals in the water is usually entirely irrelevant to the ice cube). Qualities are not objects, even if the qualities a thing possesses somehow bubble up from the objects that compose it.1

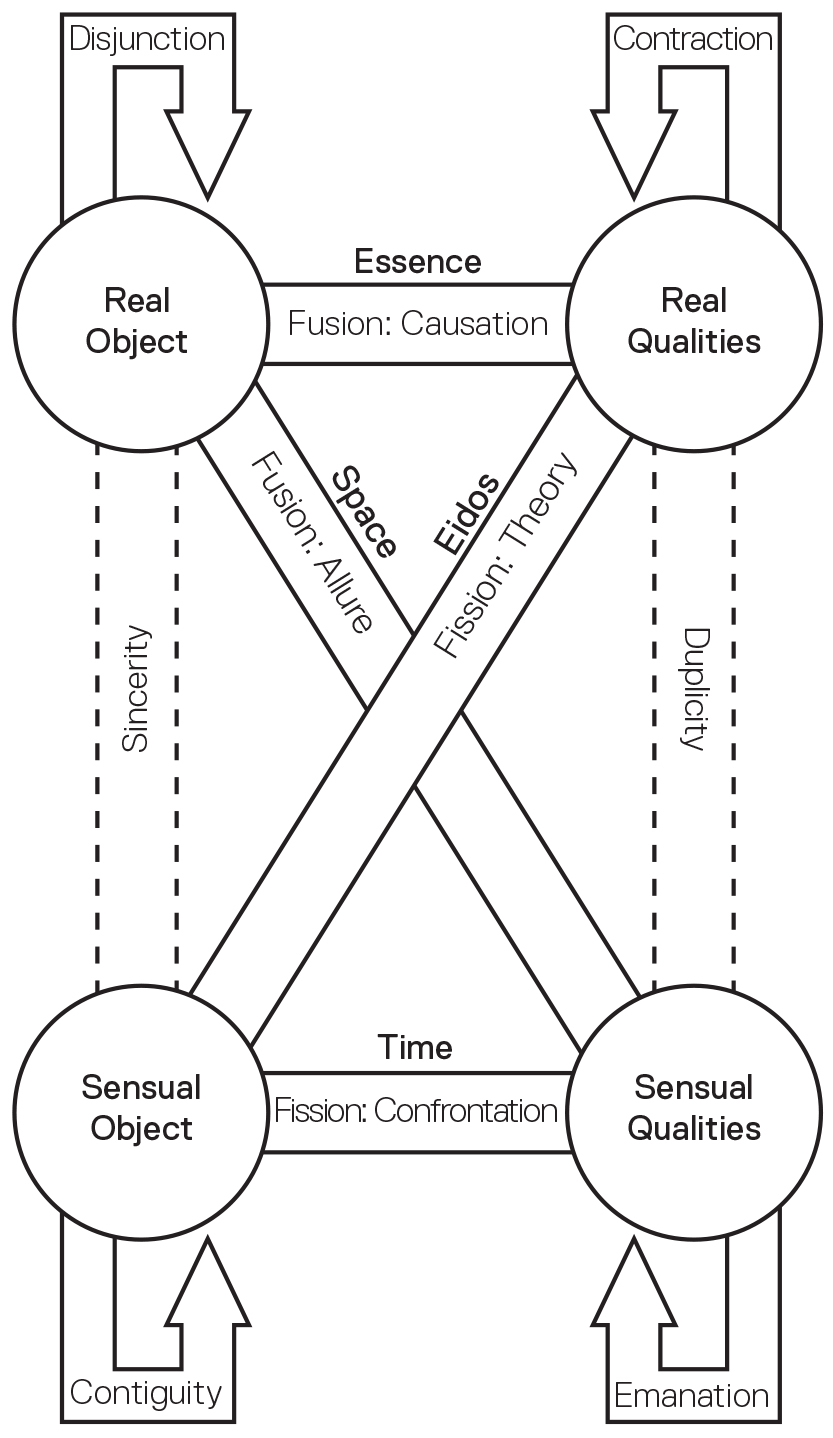

These two distinctions—real/sensual and object/quality—are not merely parallel, but cut across one another. This produces a fourfold of terms: in addition to the distinction between sensual objects (SO) and real objects (RO), there is a distinction between sensual qualities (SQ) and real qualities (RQ). The objects that appear in our phenomenal experience are ‘encrusted’ with sensible features that may vary from moment to moment, but the latter are entirely distinct from the real features ‘submerged’ in the silent execution they conceal. Here we begin to see how the four poles interact with one another to form Harman’s ten categories. The relation between a sensual object and its sensual qualities (SO–SQ) is the condition of the variation of its encrusted accidents, or time itself, whereas the relation between a sensual object and its real qualities (SO–RQ) is the submerged anchor around which this variation is fixed, or what Edmund Husserl calls eidos. These two categories are the first of what Harman calls the ‘tensions’ between object and quality. The emergence of sensual objects in our experience is dependent upon the sensible features the corresponding real objects allow them to present from perspective to perspective; and the distinctness of these underlying real objects is in turn dependent upon differences between the features they can never present. This gives us the remaining two tensions. The relation between a real object and its sensual qualities (RO–SQ) is the condition under which it can relate to another object through a sensuous facade, or space, whereas the relation between a real object and its real qualities (RO–RQ) is its principle of uniqueness, or what Xavier Zubiri calls essence. Taken together, these four tensions provide the schema of sameness and difference between objects, both real and apparent, along with their constancy and variation.

Harman calls the changes that emerge within this schema ‘fissions’ and ‘fusions’. This is because two of the tensions (time and eidos) involve a persistent state of connection between object and quality—so that any change would entail fission of this connection—and the other two (space and essence) involve a persistent state of separation—so that any change would entail fusion of that which is separated.

Fissions. It is important to recognise that the fissions take place within the sensual realm, insofar as they involve breaks in the connections between the sensual objects we experience and their qualities. In confrontation, a sensual object is split from its sensual qualities (time), so that its accidental features are somehow revealed as accidental. This occurs when we recognise something as something (e.g., a tree as a gallows), thereby separating those qualities that are relevant to this characterisation (e.g., height, branch structure, etc.) from those that are not (e.g., colour, foliage, etc.). In theory, the sensual object is split from its real qualities (eidos), so that its eidetic features are somehow contrasted with its accidental ones. This occurs when we strive to grasp the constants that underlie the shifting surface variations to which all things are subject (e.g., when we analyse the tree’s morphology, or its genetic structure).

Fusions. By contrast, only one of the fusions marks the emergence of real objects within the phenomenal sphere, so as to redraw its boundaries from within; whereas the other fusion is entirely withdrawn, and therefore is only apparent in the ways it redraws these boundaries from without. The first fusion is allure, where a real object interacts with the features of the sensible facades it projects (space), such that there is an apparent juxtaposition between its accidental elements and its eidetic core. This occurs in various aesthetically significant experiences (e.g., cuteness, beauty, humour, embarrassment, humility, disappointment, loyalty),2 but is most prominently manifest in the use of metaphor (e.g., when we frame our experience of the tree by describing it as ‘a flame’). The second fusion is causation, where the real object interacts with its own real features (essence) so as to unlock its capacities to affect the withdrawn core of other things. As already indicated, the possibility of causation is called into question by withdrawal, and this in turn necessitates the theory of vicarious causation, which will turn upon the real object’s relation with allure.

Before getting into this though, we must examine the remaining six categories, which are divided into ‘radiations’ between qualities and qualities, and ‘junctions’ between objects and objects. Much as there was a rift between one of the tensions and the other three with regard to their role in experience, there is a crucial difference between the roles that radiations and junctions play therein. On the one hand, the radiations cover the way that qualities are related within experience by the sensual objects that populate it: the relation between two sensual qualities (SQ–SQ) is their emanation through the same object of experience, the relation between two real qualities (RQ–RQ) is their contraction behind this same object, and the relation between the sensual qualities and the real qualities (SQ–RQ) is their duplicity in the way they differ from one another. On the other hand, the junctions cover the way that relations between objects constitute experience in relation to ourselves qua real objects: the relation between two sensual objects (SO–SO) can only take place as contiguity within our experience, the relation between two real objects (RO–RO) is the withdrawal of the corresponding real objects behind our experience, and the relation between a real object and a sensual object (RO–SO) is the sincerity that constitutes this experience itself. Together, the three radiations and three conjunctions provide the framework in which the three experiential tensions can unfold. They give us an abstract map of the phenomenal realms that lie between infernal kingdoms of execution—the borderlands through which they smuggle causal contraband, or the embassies through which they communicate.