My first introduction to the extraordinary little animals known as kusimanses took place at the London Zoo. I had gone into the Rodent House to examine at close range some rather lovely squirrels from West Africa. I was just about to set out on my first animal-collecting expedition, and I felt that the more familiar I was with the creatures I was likely to meet in the great rain-forest, the easier my job would be.

After watching the squirrels for a time, I walked round the house peering into the other cages. On one of them hung a rather impressive label which informed me that the cage contained a creature known as a kusimanse (Crossarchus obscurus) and that it came from West Africa. All I could see in the cage was a pile of straw that heaved gently and rhythmically, while a faint sound of snoring was wafted out to me. As I felt that this animal was one I was sure to meet, I felt justified in waking it up and forcing it to appear.

Every zoo has a rule I always observe, and many others should observe it too: not to disturb a sleeping animal by poking it or throwing peanuts. They have precious little privacy as it is. However, I ignored the rule on this occasion and rattled my thumbnail to and fro along the bars. I did not really think this would have any effect. But as I did so a sort of explosion took place in the depths of the straw, and the next moment a long, rubbery, tip-tilted nose appeared, to be followed by a rather rat-like face with small neat ears and bright inquisitive eyes. This little face appraised me for a minute; then, noticing the lump of sugar which I held tactfully near the bars, the animal uttered a faint, spinsterish squeak and struggled madly to release itself from the cocoon of straw wound round it.

When only the head had been visible, I had the impression it was only a small creature, about the size of the average ferret, but when it eventually broke loose from its covering and waddled into view, I was astonished at its relatively large body: it was, in fact, so fat as to be almost circular. Yet it shuffled over to the bars on its short legs and fell on the lump of sugar I offered, as though that was the first piece of decent food it had received in years.

It was, I decided, a species of mongoose, but its tip-tilted, whiffling nose and the glittering, almost fanatical eyes made it look totally unlike any mongoose I had ever seen. I was convinced now that its shape was due not to Nature but to overeating. It had very short legs and fine, rather slender paws, and when it trotted about the cage these legs moved so fast that they were little more than a blur beneath the bulky body. Each time I fed it a morsel of food it gave the same faint, breathless squeak: as much as to reproach me for tempting it away from its diet.

I was so captivated by this little animal that before I realized what I was doing I had fed it all the lump-sugar in my pocket. As soon as it knew that no more titbits were forthcoming, it uttered a long-suffering sigh and trotted away to dive into the straw. Within a couple of seconds it was sound asleep once more. I decided there and then that if kusimanses were to be obtained in the area I was visiting, I would strain every nerve to find one.

Three months later I was deep in the heart of the Cameroon rainforests and here I found I had ample opportunity for getting to know the kusimanse. Indeed, they were about the commonest members of the mongoose family, and I often saw them when I was sitting concealed in the forest waiting for some completely different animal to make its appearance.

The first one I saw appeared suddenly out of the undergrowth on the banks of a small stream. He kept me amused for a long time with a display of his crab-catching methods: he waded into the shallow water and with the aid of his long, turned-up nose (presumably holding his breath when he did so) he turned over all the rocks he could find until he unearthed one of the large, black, freshwater crabs. Without a second’s hesitation he grabbed it in his mouth and, with a quick flick of his head, tossed it on to the bank. He then chased after it, squeaking with delight, and danced round it, snapping away until at last it was dead. When an exceptionally large crab succeeded in giving him a nip on the end of his retroussé nose, I am afraid my stifled amusement caused the kusimanse to depart hastily into the forest.

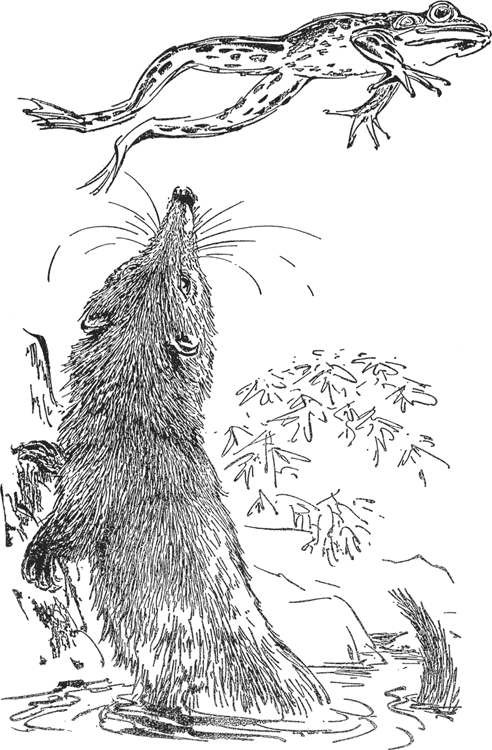

On another occasion I watched one of these little beasts using precisely the same methods to catch frogs, but this time without much success. I felt he must be young and inexperienced in the art of frog-catching. After much laborious hunting and snuffling, he would catch a frog and hurl it shorewards; but, long before he had waddled out to the bank after it, the frog would have recovered itself and leapt back into the water, and the kusimanse would be forced to start all over again.

One morning a native hunter walked into my camp carrying a small palm-leaf basket, and peering into it I saw three of the strangest little animals imaginable. They were about the size of new-born kittens, with tiny legs and somewhat moth-eaten tails. They were covered with bright gingery-red fur which stood up in spikes and tufts all over their bodies, making them look almost like some weird species of hedgehog. As I gazed down at them, trying to identify them, they lifted their little faces and peered up at me. The moment I saw the long, pink, rubbery noses I knew they were kusimanses, and very young ones at that, for their eyes were only just open and they had no teeth. I was very pleased to obtain these babies, but after I had paid the hunter and set to work on the task of trying to teach them to feed, I began to wonder if I had not got more than I bargained for. Among the numerous feeding-bottles I had brought with me I could not find a teat small enough to fit their mouths, so I was forced to try the old trick of wrapping some cotton-wool round the end of a matchstick, dipping it in milk and letting them suck it. At first they took the view that I was some sort of monster endeavouring to choke them. They struggled and squeaked, and every time I pushed the cotton-wool into their mouths they frantically spat it out again. Fortunately it was not long before they discovered that the cotton-wool contained milk, and then they were no more trouble, except that they were liable to suck so hard in their enthusiasm that the cotton-wool would part company with the end of the matchstick and disappear down their throats.

At first I kept them in a small basket by my bed. This was the most convenient spot, for I had to get up in the middle of the night to feed them. For the first week or so they really behaved very well, spending most of the day sprawled on their bed of dried leaves, their stomachs bulging and their paws twitching. Only at meal-times would they grow excited, scrambling round and round inside the basket, uttering loud squeaks and treading heavily on one another.

It was not long before the baby kusimanses developed their front teeth (which gave them a firmer and more disastrous grip on the cotton-wool), and as their legs got stronger they became more and more eager to see the world that lay outside their basket. They had the first feed of the day when I drank my morning tea; and I would lift them out of their basket and put them on my bed so that they could have a walk round. I had, however, to call an abrupt halt to this habit, for one morning, while I was quietly sipping my tea, one of the baby kusimanses discovered my bare foot sticking out from under the bedclothes and decided that if he bit my toe hard enough it might produce milk. He laid hold with his needle-sharp teeth, and his brothers, thinking they were missing a feed, instantly joined him. When I had locked them up in their basket again and finished mopping tea off myself and the bed, I decided these morning romps would have to cease. They were too painful.

This was merely the first indication of the trouble in store for me. Very soon they had become such a nuisance that I was forced to christen them the Bandits. They grew fast, and as soon as their teeth had come through they started to eat egg and a little raw meat every day, as well as their milk. Their appetites seemed insatiable, and their lives turned into one long quest for food. They appeared to think that everything was edible unless proved otherwise. One of the things of which they made a light snack was the lid of their basket. Having demolished this they hauled themselves out and went on a tour of inspection round the camp. Unfortunately, and with unerring accuracy, they made their way to the one place where they could do the maximum damage in the minimum time: the place where the food and medical supplies were stored. Before I discovered them they had broken a dozen eggs and, to judge by the state of them, rolled in the contents. They had fought with a couple of bunches of bananas and apparently won, for the bananas looked distinctly the worse for wear. Having slaughtered the fruit, they had moved on and upset two bottles of vitamin product. Then, to their delight, they had found two large packets of boracic powder. These they had burst open and scattered far and wide, while large quantities of the white powder had stuck to their egg-soaked fur. By the time I found them they were on the point of having a quick drink from a highly pungent and poisonous bucket of disinfectant, and I grabbed them only just in time. Each of them looked like some weird Christmas cake decoration, in a coat stiff with boracic and egg yolk. It took me three quarters of an hour to clean them up. Then I put them in a larger and stronger basket and hoped that this would settle them.

It took them two days to break out of this basket.

This time they had decided to pay a visit to all the other animals I had. They must have had a fine time round the cages, for there were always some scraps of food lying about.

Now at that time I had a large and very beautiful monkey, called Colly, in my collection. Colly was a colobus, perhaps one of the most handsome of African monkeys. Their fur is coal black and snow white, hanging in long silky strands round their bodies like a shawl. They have a very long plume-like tail, also black and white. Colly was a somewhat vain monkey and spent a lot of her time grooming her lovely coat and posing in various parts of the cage. On this particular afternoon she had decided to enjoy a siesta in the bottom of her box, while waiting for me to bring her some fruit. She lay there like a sunbather on a beach, her eyes closed, her hands folded neatly on her chest. Unfortunately, however, she had pushed her tail through the bars so that it lay on the ground outside like a feathery black-and-white scarf that someone had dropped. Just as Colly was drifting off into a deep sleep, the Bandits appeared on the scene.

The Bandits, as I pointed out, believed that everything in the world, no matter how curious it looked, might turn out to be edible. In their opinion it was always worth sampling everything, just in case. When he saw Colly’s tail lying on the ground ahead, apparently not belonging to anyone, the eldest Bandit decided it must be a tasty morsel of something or other that Providence had placed in his path. So he rushed forward and sank his sharp little teeth into it. His two brothers, feeling that there was plenty of this meal for everyone, joined him immediately. Thus was Colly woken out of a deep and refreshing sleep by three sets of extremely sharp little teeth fastening themselves almost simultaneously in her tail. She gave a wild scream of fright and scrambled towards the top of her cage. But the Bandits were not going to be deprived of this tasty morsel without a struggle, and they hung on grimly. The higher Colly climbed in her cage, the higher she lifted the Bandits off the ground, and when eventually I got there in response to her yells, I found the Bandits, like some miniature trapeze-artists, hanging by their teeth three feet off the ground. It took me five minutes to make them let go, and then I managed it only by blowing cigarette-smoke in their faces and making them sneeze. By the time I had got them safely locked up again, poor Colly was a nervous wreck.

I decided the Bandits must have a proper cage if I did not want the rest of my animals driven hysterical by their attentions. I built them a very nice one, with every modern convenience. It had a large and spacious bedroom at one end, and an open playground and dining-room at the other. There were two doors, one to admit my hand to their bedroom, the other to put their food into their dining-room. The trouble lay in feeding them. As soon as they saw me approach with a plate they would cluster round the doorway, screaming excitedly, and the moment the door was opened they would shoot out, knock the plate from my hand and fall to the ground with it, a tangled mass of kusimanses, raw meat, raw egg and milk. Quite often when I went to pick them up they would bite me, not vindictively but simply because they would mistake my fingers for something edible. Yes, feeding the Bandits was not only a wasteful process but an extremely painful one as well. By the time I got them safely back to England they had bitten me twice as frequently as any animal I have ever kept. So it was with a real feeling of relief that I handed them over to a zoo.

The next day I went round to see how they were settling down. I found them in a huge cage, pattering about and looking, I felt, rather lost and bewildered by all the new sights and sounds. Poor little things, I thought, they have had the wind taken out of their sails. They looked so subdued and forlorn. I began to feel quite sorry to have parted with them. I stuck my finger through the wire and waggled it, calling to them. I thought it might comfort them to talk to someone they knew. I should have known better: the Bandits shot across the cage in a grim-faced bunch and fastened on to my finger like bulldogs. With a yelp of pain I at last managed to get my finger away, and as I left them, mopping the blood from my hand, I decided that perhaps, after all, I was not so sorry to see the back of them. Life without the Bandits might be considerably less exciting – but it would not hurt nearly so much.