The past decades have witnessed a tremendous outpouring of scholarly books and articles dealing with urban tourism. Most of these contributions agree that tourism in cities has grown substantially and that this growth is paralleled by equally substantial changes in the way tourism is being perceived – and dealt with – in cities’ political arenas. Whereas tourism in most cities was, until well into the 1970s, only of little interest to policy-makers and other local elites, tourism since then has evolved into a key policy concern in cities throughout the advanced capitalist world. Today, as Fainstein et al. (2003: 8) note, ‘virtually every city sees a tourism possibility and has taken steps to encourage it.’ Berlin has been no exception. Many scholars have argued that tourism ever since the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 has played an important role in the city’s economic and urban development policies (Colomb 2011; Krajewski 2006; Novy and Huning 2009). Berlin’s popularity as a destination, if anything, contributed to the impetus for tourism promotion. While the city suffered for the most part of the 1990s and early 2000s from a declining or stagnating urban economy, tourism belongs to the few economic sectors that have seen vertiginous and almost uninterrupted growth since 1989. Visitor numbers in paid accommodations alone have almost quadrupled since the early 1990s to a record-breaking 11.8 million annual visitors and more than 28 million overnight stays in 2014, making Berlin Europe’s third most popular urban tourism destination after Paris and London. If the current growth rate is maintained, the latest official target of 30 million overnight stays set for 2020 will be reached several years ahead of schedule and city officials already dream of surpassing Paris which recorded 36.6 million overnight stays in 2014 (Matthies 2014). Accordingly, tourism’s economic impact has also increased considerably – as of 2014 it was estimated to contribute an astonishing 10.6 per cent to the city’s gross domestic product (Nicola 2014).1

Given such figures, it is not surprising that tourism – at least rhetorically – is held in high esteem in Berlin’s political arena. Policy-makers regularly praise the sector as a main driver of the city’s economy and pledge their commitment to boost its development further. There is no paucity of rhetoric that lends support to the widely held view that tourism is afforded ‘high priority (. . .) by city leaders’ (Fainstein et al. 2003: 2). Rhetoric is one thing, while policy enactment is another, however, and while developments in Berlin in many ways appear to be in tune with dominant interpretations about tourism’s rise to prominence as a policy concern, there are also aspects that challenge such interpretations. Tourism promotion in the context of wider place marketing activities has become a defining feature of Berlin’s increasingly entrepreneurial approach to urban and economic development, but there are at the same time clear limitations with respect to local authorities’ engagement with tourism. These limitations have become increasingly more apparent as tourism, after years of being effectively depoliticized and treated in technocratic fashion, became increasingly controversially discussed and contested. The city’s approach to tourism is characterized by a host of contradictions, lacunae and inconsistencies that have led both those critical of tourism as well as tourism advocates to call for change. Whereas the latter are mainly concerned about the adverse effects resulting from tourism’s growth for inner-city neighbourhoods and their inhabitants, the former act out of a concern about the future prospects of Berlin as a destination. They know that tourism carries within itself the ‘seeds of its own destruction’, that is that tourism, if unchecked and not properly planned for, can harm and even potentially destroy the very attributes and resources a destination’s success relies upon.

This chapter aims to elaborate on the situation in Berlin in greater depth and will discuss its implications for our scholarly understanding of urban tourism as a policy field as well as the (future) development of the destination Berlin. It is based on more than ten years of research and fieldwork, involving interviews, participant observation and archival research.2 The chapter will start with a short discussion of key theoretical and empirical contributions concerning the relevance of urban tourism as a policy concern in present-day cities. Embedded in a discussion of tourism’s trajectory since the city’s reunification and the key tenets of urban development and governance that shaped it, the next sections focus on the development of tourism policy and politics and what I term the de- and re-politicization of urban tourism in post-1989 Berlin. They will first demonstrate that Berlin’s tourism policy in practice is replete with lacunae and contradictions, and that beyond promotional activities, it remains in an underdeveloped and fragmented state. Subsequently, by focusing particularly on the recent controversies surrounding tourism’s growth in Kreuzberg and other centrally located neighbourhoods, the (re-)politicization of tourism as well as the reactions it sparked will be discussed. Characterizing the reality of tourism as a policy field and area of public sector intervention as inherently complex, contradictory and inchoate, the chapter’s final section will reflect upon the causes and consequences of local authorities’ rather limited engagement with tourism to date and notable absence of tourism planning and management.

Urban tourism, ‘new urban politics’ and public policy

The heightened importance of urban tourism as well as the forces underlying its rise to prominence are well documented (see the introduction to this volume) and do not need to be rehearsed at great length. There is now a large body of literature that attests that urban tourism has evolved into an extremely important economic and social phenomenon as well as a critical force of urban change (see, inter alia, Law 2002; Hoffman et al. 2003; Selby 2004; Spirou 2011). Similarly, it is well established that the heightened relevance of urban tourism is illustrative of broader transformations with regard to the role and function of cities as well as equally fundamental changes in production, consumption and mobility patterns in North America, Western Europe and many other parts of the world. Simply put, two closely related real-world phenomena have been at play from the late 1970s onwards: an escalating growth of tourism in cities as well as a growing economic but also symbolic importance of tourism as a result of broader restructuring processes in which service-, knowledge- and consumption-based industries came to take on a critical role for cities’ economic well-being and ‘competitive edge’.

Referred to variously as post-industrial, postmodern or post-Fordist, these restructuring processes have been paralleled and accompanied by important governmental changes at a range of geographical scales, including, on the local level, by what has come to be known as a shift from managerial to entrepreneurial or, more recently, neoliberal local governance (Harvey 1989; Hall and Hubbard 1998; Brenner and Theodore 2002). This shift has been described as a move away from the traditional managerial functions of welfare and service provision towards a ‘new urban politics’ (Hall and Hubbard 1998) emphasizing growth and competitiveness. The task of urban governments thus increasingly became the creation of attractive conditions to lure new investments, residents and jobs in a context of intensifying inter-urban competition. Both policy-makers and scholars in this context quickly identified urban tourism as an important issue for future policy: on the one hand because of its potential as an economic sector in its own right; on the other because of its ‘symbolic weight’, as tourism increasingly came to be seen as a major mechanism to boost a city’s image and bring new life to areas affected by deindustrialization and decline (Fainstein et al. 2003: 2; see also Selby 2004: 16). Framed within a broad array of what the literature refers to as ‘place marketing’ strategies (Philo and Kearns 1993: 3) and indicative of the so-called ‘festivalization’ of urban politics (Häußermann and Siebel 1993), increasing investments in tourist-oriented attractions, festivals and events as well as tourism marketing are perhaps the most palpable manifestations of the increasingly proactive stance towards tourism that from the 1970s came to characterize urban policy. This has led many authors to argue that urban tourism, as part of a more general shift in urban policy towards leisure and consumption, had ‘rightly or wrongly’ become ‘a cornerstone of modern urban management’ (van der Borg 1991: 2).

What is surprising, however, is that comprehensive analyses concerning tourism politics and policy-making in cities remain few and far between. Scholars have produced well-informed studies on specific aspects – e.g. the effectiveness or efficiency of tourism policy in regeneration attempts, the role of public–private partnerships or ‘regimes’ in tourism development, etc. – but comprehensive studies of the politics of tourism, including the local state’s involvement in tourism as well as the institutional arrangements, decision-making processes, interests and conflicts that shape policy-making, continue to be rare. With regard to cities, Hall’s (2006: 260) famous dictum about the state of tourism politics research thus still holds true: considering the profound effects associated with tourism, it is indeed remarkable ‘how little attention is given to the way in which tourism is governed and directed.’

The few studies that have looked at these issues suggest that the extent of the changes brought about by urban entrepreneurialism should not be overstated. They argue that city governments have, to varying degrees, pursued tourism promotion strategies for a long time (e.g. the nineteenth century) and that the growing recognition of tourism as a key issue in today’s ‘selling’ of cities has not automatically resulted in a greater recognition and institutionalization of tourism as a policy field. Discussing the state of tourism policy in English cities, Stevenson et al. (2008: 744), for instance, found that tourism policy is often accorded a low status in cities’ political arenas, which ‘arises from its discretionary nature, a lack of clarity about what it is and how it fits with other more established areas, and a lack of interest from the local electorate and local politicians’. Van der Borg et al. (1996: 316), looking at heritage destinations, came to similar conclusions and found that the ‘principle of laissez faire (. . .) dominated the attitudes of policy-makers and entrepreneurs towards tourism development’ and that ‘explicit tourism management policy that goes beyond promotion alone’ was few and far between. Such perspectives do not question the widely held view about tourism’s growing relevance in urban and economic policy per se, but they question the conventional wisdom about tourism’s supposed importance in contemporary urban policy. They illustrate that this importance does not necessarily, as occasionally assumed, translate into ‘a rich(er) institutional structure to regulate local tourism’ (Fainstein et al. 2003: 6) and that there appear to be limitations with regard to local authorities’ engagement with tourism. These limitations, according to some scholars, have become not less but more conspicuous in recent decades as a result of what has been termed the ‘hollowing out of the state’ (Jessop 1994), that is the increasing delegation and/or privatization of functions previously within the remit of public authorities. According to these perspectives, the rise of what became known as the ‘new urban politics’, and the underlying neoliberal public-sector reforms, have profoundly transformed both the objectives of tourism policy and the mechanisms for achieving them.

Hall (1999, cited in Hall and Jenkins 2004: 528), for example, posits that the role of government in tourism has undergone a ‘dramatic shift from a traditional public administration model which sought to implement government policy for a perceived public good, to a corporatist model which emphasizes efficiency, investment returns, the role of the market, and relations with stakeholders, usually defined as industry’. According to him as well as a number of other scholars (see Pastras and Bramwell 2013; Dredge and Jenkins 2011), the pendulum has swung toward both more and less government interference in the tourism field. Tourism agencies and boards have been outsourced to public-private or to completely private companies acting as ‘municipal agents’; the state’s role in coordinating and directing tourism activities has been reduced to that of a facilitator of tourism growth and the provision of a suitable environment for businesses to thrive; and not local officials but private sector actors often set cities’ agendas as to how tourism is dealt with.

The reasons for this shift are rooted in the assumptions underlying the rise of neoliberal reforms: the idea that markets are generally self-regulating and should whenever possible be left to work on their own; the hegemonic belief that what is good for the economy is good for society; and the conviction that private sector actors know best what would make them prosper and consequently should be given a strong position in policy-making (see Dredge and Jenkins 2011). One notable consequence of the above-mentioned shift has been that tourism, not unlike other policy areas (see Wilson and Swyngedouw 2014), has effectively been depoliticized in two ways. On the one hand, a discursive normalization and naturalization of neoliberal practices and approaches could be observed, making tourism development – as well as measures to promote it – a largely uncontroversial matter of technicalities rather than of political interests, potential conflicts and power. On the other hand, tourism has been in many contexts practically removed from the public realm of the formal political sphere: privatization and corporatization as well as backroom deal-making and so-called ‘public-private partnerships’ took hold and not only excluded many groups and communities from relevant decision-making processes, but ultimately also called the primacy of political institutions as having formative power to shape social life into question.

Berlin, a city in which tourism had been highly politicized for much of the twentieth century (albeit under different circumstances and in a different sense than today),3 until recently exemplified this situation particularly well. This has changed: recent years have witnessed a proliferation of protests and mobilizations around tourism and the city government’s approach to it. As a result, many questions that had been depoliticized and taken for granted have effectively been re-politicized: the costs and benefits of tourism, their distribution, as well as the question of how the local state should approach tourism are now being publicly discussed.

Tourism in Berlin: political priority, political afterthought, or both?

As with any public policy in more general terms, tourism policy involves more than formal, identifiable decisions or directives by governments. It has been defined as ‘whatever governments choose to do or not to do with respect to tourism’ (Hall and Jenkins 2004: 527; see also Hall 1994; Jenkins 1993). It is also, with reference to the alleged shift from government to governance, considered to extend beyond the sphere of formal government structures to involve action, inaction, decisions and non-decisions by other, non-state actors active in the policy process. To this end, scholars have highlighted the role of ‘policy networks’ (Laslo 2003) or ‘policy communities’ (Dredge 2004) comprising those who have a stake in tourism, as well as of urban ‘regimes’ or ‘coalitions’ (Fainstein and Gladstone 2003), in shaping tourism policy and development. A case in point is Häußermann and Colomb’s (2003) discussion of tourism development in Berlin in the 1990s and early 2000s. In it, they argued that a public-private ‘tourism coalition’ made of Berlin’s government (Senate) and other (private) actors with a stake in tourism had been instrumental in making tourism a priority in the city’s economic and urban development policy.4 Their analysis, however, left a lot of questions unanswered concerning the actual character of tourism politics and policy-making. Place marketing and urban development efforts aimed at ‘re-invent(ing) Berlin as a post-industrial service metropolis’ (ibid.: 201) and enhancing the city’s image as an attractive place to live, work, play and invest in are extensively elaborated upon, but relatively little is said about the specific field of urban tourism policy, the city-state’s and other actors’ approach to it, and their relationships to one another. What role, then, did tourism play in Berlin’s political arena after the city’s reunification and, more specifically, how can the attitudes and actions of the local state towards tourism development be described? As will be discussed in the following sections, evidence offers a somewhat contradictory picture with respect to this question. Tourism throughout the past decades seems to have been both the object of substantial attention as well as, paradoxically, of continuous and at times callous disregard.

Reunited and redefined. Destination Berlin, 1989–2010

Berlin’s rise to fame as one of Europe’s most sought after tourist destination began with a significant event: the collapse of the Berlin Wall in November 1989 paved the way for Germany’s reunification, which was formally concluded on 3 October 1990 and led to a massive surge of tourism. Streams of visitors from all over the globe flocked into the city to sense the festive atmosphere that engulfed Berlin as world history unfolded. Accordingly, Berlin registered record-breaking numbers of hotel guests and overnight stays: 7.2 million overnight stays were recorded in 1992 alone, the highest figures ever recorded by West Berlin’s Office for Statistics. Revenues for hotels, restaurants, bars, souvenir stores and other businesses benefiting from tourism all jumped to record levels and in doing so conveyed a first powerful sense of tourism’s economic potency (Nerger 1998: 814). In the immediate aftermath of the city’s reunification, tourism was, meanwhile, of secondary importance in the local political arena. This is because major decisions about the city’s future development had to be made, the reintegration of the two halves of the city had to be organized, and the German parliament’s decision to move the government seat from Bonn back to Berlin compounded the daunting challenges officials found themselves confronted with. Politically, tourism first became a topic of discussion in 1992.

Three years after the fall of the Wall, amid dropping visitor numbers and falling revenues, policy-makers, tourism industry representatives as well as the Chamber of Commerce called for measures to stem the tide and put the tourism sector back on the growth track. The main issue under discussion was the perceived need to reorganize and strengthen the city’s tourism marketing activities (see Colomb 2011). At the time, tourism marketing was managed by two public sector organizations – the Fremdenverkehrsamt and the Informationszentrum Berlin – and the ruling Grand Coalition of Christian Democrats (CDU) and Social Democrats (SPD) as well as private sector representatives agreed that more ‘effective’ and ‘up-to-date’ tourism marketing was needed. As a consequence, the decision was made to replace the two organizations that had previously dealt with the tourism promotion of West Berlin with a new public-private partnership – the Berlin Tourismus Marketing GmbH (BTM). Set up in 1993 and later renamed Visit Berlin, the BTM was established to fulfil two main roles: that of a service agency for its partners in the tourism industry, and that of an active broker for the travel industry and for tourists and travellers to Berlin (Colomb 2011). With this step, Berlin’s policy-makers created a key element of the organizational structure that would shape tourism-related activities for years to come. This organizational structure was completed in 1994 when Partner für Berlin (‘Partners for Berlin, Company for Capital City Marketing’) was established in order to provide support for the repositioning of Berlin as Germany’s new capital city and, in the words of its originators, ‘foster [. . .] Berlin’s image as a leading, competitive, future-oriented and international metropolis’ (Partner für Berlin 1998).5

Notably, representatives of the private sector play a pivotal role in both organizations – both as shareholders and on the companies’ boards.6 Tied to the general shift of the time towards greater private sector involvement, the local state hence transferred many responsibilities it had previously performed in the realm of tourism marketing to new arrangements that – while in many ways reliant on public funding and contracts – are private in character and not part of the governmental apparatus. Within the latter, tourism remained a concern within the city’s economic development department. Apart from small-scale measures aimed at assisting the tourism industry, the department’s engagement, however, was mainly limited to acting as an interface between the public sector, the newly established marketing organizations as well as the tourism industry. The city’s urban development department, meanwhile, engaged in activities to facilitate tourism growth and promote the city as a destination, but rarely did so in explicit terms. Few of its activities were devoted primarily to visitors and it was the BTM and, to a lesser extent, Partner für Berlin that, from the mid-1990s onwards, came to take on the leading role as the city’s quasi-public authorities for issues relating to tourism marketing and development. Debates over tourism (policy) became in the course of the 1990s increasingly dominated by their representatives and spokespersons from business groups such as the local branch of Germany’s Hotel and Restaurant Association (DEHOGA), while representatives of the state – be they members of the Berlin parliament, civil servants or elected government officials – relegated themselves increasingly to the sidelines.

Prior to the overhaul of the city-state’s tourism marketing, tourism had been the subject of heated parliamentary debates that not only revolved around the promotional activities advocated by the Grand Coalition but also involved more general discussions about the role and relevance that should be ascribed to tourism politically as well as the kind of tourism that should be promoted. Once the new organizational structure was in place, such discussions became increasingly rare. Little explicit tourism policy to discuss and contest, as well as the fact that there were other urgent issues on the political agenda are sometimes cited as reasons for this. In light of the massive economic and social problems that characterized Berlin at the time, it is not all that surprising that tourism took a back seat in favour of other controversial issues – especially since tourism, in stark contrast to the poor performance of Berlin’s economy as a whole, experienced accelerating growth in the course of the mid and late 1990s. The problematic or outright negative side effects of that growth were, at first, not that evident or at least not of much concern. Ultimately, however, the absence of political debates on urban tourism can also be attributed to the way political practices and thinking became increasingly attuned to neoliberal rationality. The prioritization of growth as the central objective of tourism policy became almost universally accepted and with it the idea that the state’s involvement in tourism should be limited to the attainment of this goal. It was ironically under a coalition of the centre-left SPD with the socialist party Die Linke (formerly PDS), which had come into power after the demise of the Grand Coalition in 2001, that this doctrine was formalized. In the city’s first conceptual document on tourism (Tourismuskonzept) after reunification – revealingly prepared by a private consultancy firm in close cooperation with BTM – the roles of the state and of the private sector institutions were described as follows:

The task of the state is to improve the general conditions for the activities of the private sector as a precondition for employment effects, influx of purchasing power and tax income. The task of the private sector is to initiate and develop self-supporting economic cycles with ideas and capital.

(SenWI 2004: 5, cited in Colomb 2011: 235)

Capital, however, came also in significant part from the state as the ‘red-red coalition’, in spite of its more general austerity course, steadily increased funding dedicated to tourism promotion. Declaring tourism a ‘top concern’ of his administration (Sontheimer 2004a), Klaus Wowereit, the city’s mayor elected in 2001, moreover implemented a number of other initiatives to boost the city’s image as a destination and expand its tourism trade. This led Hanns Peter Nerger, BTM’s long-serving CEO, to claim that his government was doing more for the advancement of tourism in Berlin than any of its predecessors (in Sontheimer 2004b). Berlin – at a time when the city’s overall economy had hit rock bottom and the city-state teetered on the edge of bankruptcy – had entered the new millennium with record-breaking tourism growth rates. These developments – along with the fact that policy-makers had somewhat come to resign themselves to Berlin’s lack of competitiveness as a business destination – heightened the relevance that was ascribed to tourism as an economic sector with relatively low entry costs and potentially high returns as a source of revenue, employment and image building. Furthermore, tourism fitted well with the more general approach to urban and economic development the city government adopted, including in particular its efforts to target ‘creative’ people and branches as a tool for urban development and innovation. Tourism hence became an increasingly integral part, albeit often not a very explicit one, of broader creative city-policies and other ‘place selling’ efforts and by hitting new highs year after year, it not only steadily grew in economic strength but also became increasingly apparent as a powerful force of urban change.

Growth pains and growing discontent. Destination Berlin, 2010–2014

By the end of the first decade of the new millennium, the city elites’ love affair with tourism was stronger than ever before. Fuelled by constant new records in the number of visitors and overnight stays, the booming tourism trade was stylized, with the enthusiastic support of the media, as a kind of saviour for the economically troubled city (see Gitschier and Lukosek 2010). The international attention Berlin received as a destination – which earned the city the title of ‘Europe’s Capital of Cool’ in Time Magazine – added to the excitement. At the same time, however, it also became evident that that not everyone shared the excitement about Berlin’s success as a destination.

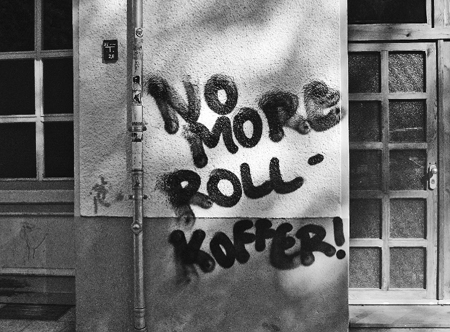

Against the backdrop of a more general discontent with the city’s transformation since its reunification, critical voices began to disturb and challenge the hitherto almost exclusively boosterist narratives surrounding tourism. Residents and community groups became increasingly vocal and raised alarm about the impacts of tourism on their communities, in particular in the mixed-use but predominantly residential neighbourhoods surrounding the city’s centre that developed in the nineteenth century expansion of the city – e.g. Kreuzberg (in the Western part, Figure 3.1), Friedrichshain and Prenzlauer Berg (in the Eastern part). These neighbourhoods had, as one newspaper described it, over the years increasingly been ‘conquered’ by tourism (Bartels 2010) and to many observers the city government was complicit in this process due to its preoccupation with growth-focused strategies aimed at selling the city to outsiders. To many critics the latter amounted to a ‘sell-out’ of the city and its inherent qualities. Along with tourism’s perceived (albeit not unequivocally substantiated) role as a contributing factor in gentrification processes, nuisance issues such as noise pollution, as well as concerns about a commercialization and ultimately ‘touristification’ of communities, this contributed to the problematization and politicization of what hitherto had essentially been a non-issue in political debates and struggles. Graffiti with slogans like ‘No more rolling suitcases’ and ‘Tourists F*** off’ became a regular sight (Figure 3.2), community meetings addressing tourism’s detrimental effects became a regular fixture, and tourists – blamed for their complicity in gentrification processes – emerged as the favourite scapegoats boys of radical left-wing groups, who claim to ‘defend’ Berlin’s neighbourhoods and its cherished ‘free spaces’.

Fiercely criticized for mistaking cause and effect, for scapegoating tourists and for its occasional xenophobic undertones (see Alas 2011), the growing discontent and protests against tourism in Berlin have been the subject of intense debates. Some protesters doubtlessly can be characterized as knee-jerk advocates of a ‘Not in My Backyard’ mindset and some manifestations of protest can be described as contemptuous or outright maliciousness. Perhaps the most palpable example of the latter is the much publicized ‘Proposal for an anti-tourism campaign 2011’ by the leftist magazine Interim. It declared tourists to be legitimate targets in the fight against gentrification and encouraged readers to steal phones and wallets from visitors and engage in all sorts of other hostile and intimidating activities so as so as to scare them away (see Hasselmann 2010).

Figure 3.1 Kreuzberg: impressions of a neighbourhood in flux.

Sources (from left to right): Ya Po Guille (CC BY-ND 2.0), Alper Çuğun (CC BY 2.0), Uli Herrmann (CC BY-SA 2.0), Ben Garrett (CC BY 2.0).

Such views have attracted a disproportionate amount of media attention but can hardly be described as representative of the protests as a whole. As regards the composition of the actors behind the latter and the agendas they pursue, it is important to note that there is no readily identifiable core, let alone single coordinating body that directs them. Instead, different groups and individuals with different backgrounds, motives and methods problematize tourism independently of one another and many of them have far less in common with one another than many of the media’s generalizing portrayals of Berlin’s alleged ‘tourist hate’ (Huffington Post 2012) suggest. Among those expressing discontent are old residents fearful of gentrification, but also gentrifiers fearing for their quality of life and capital gains. Others are mainly concerned about tourism’s cultural impacts such as the much-decried ‘disneyfication’ of Berlin’s ambiguous historic heritage. A surprisingly large number happen to be beneficiaries of the tourism trade themselves. The owner of Freies Neukölln, a now defunct bar in the increasingly sought after neighbourhood of Neukölln, is one such example. The bar used to be popular with international ‘party tourists’ and its owner caused considerable uproar with a video entitled Offending the Clientele that criticized its patrons for their indifference to the former working-class and migrant neighbourhood’s extant character and provocatively attacked them – supposedly to generate debate – for being responsible for the area’s rampant gentrification.

One may argue that it would have been more constructive to point the finger not at visitors, but at those responsible for the city’s development and the regulation of tourism activities. This is exactly what others have done, such as Andreas Becker, the director of the Circus Hostel, one of the city’s most popular low-cost accommodations. He contended that the conflicts surrounding tourism, including in particular those arising from the excessive ‘party tourism’ that regularly concentrates in certain areas, can be attributed to the local state’s unwillingness to engage in tourism management and planning. ‘The city has failed’, he argued, adding that the resulting damage to the city’s image and the tourism sector’s reputation would be disastrous for the tourism industry (cited in Lüber 2014). This is not the only instance where tourism industry members have publicly criticized the city’s approach to tourism development – or lack thereof. Critiques have also been raised about the unregulated boom of hotels and hostels (whose number has more than quintupled since 1993) and the resulting crowding out of small, independently owned accommodation, as well as the proliferation of short-term vacation rentals in the city. Exact figures do not exist, but recent estimates suggest that there are up to 23,000 of the latter in the city (Aulich 2015). A major bone of contention for many residents and tenant organisations who argue that they drive up housing prices and lessen the supply of regular rental units, these rentals are also viewed critically by many in the tourism industry as they provide competition to hotels, inns and bed-and-breakfasts. Such examples reveal that the tourism industry is not monolithic but made up of different players with different opinions and interests, and that not all of them subscribe to the laissez-faire approach to tourism adopted by the local state in the 1990s.

Significantly, the same must also be said of the ‘local state’. The district government of Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg emerged, for instance, over the years as one of the fiercest critics of the Senate’s handling of tourism-related matters.7 Centrally located and often described as one of Berlin’s liveliest and vibrant districts, Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg experienced a particularly strong influx of tourists since the early 1990s. In addition – perhaps unsurprisingly given the district’s history as a major centre of political activism and countercultural activity – it is also one of the areas in which tourism is most controversially discussed. Local officials have in this context frequently sided with local residents and community groups who campaigned against the proliferation of holiday accommodation or took issue with other tourism-induced changes impacting their neighbourhoods.

Figure 3.2 ‘No more Rollkoffer [rolling suitcases]’. Anti-tourism graffiti in Berlin’s public space, 2011.

Source: Jörg Kantel, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

It was the local branch of the Green Party (which has led the district council since 2006) that organized a controversial community meeting under the title ‘Help, the tourists are coming!’ in 2011, which led the media to depict the district as the epicentre of the rise of ‘tourist-haters’ (Haas et al. 2011). The district council’s own capacity to impact the dynamics of tourism within its boundaries is, however, relatively limited. It acted several times in a manner which stretched its powers to the limits to block the construction of new hotels and hostels (Myrrhe 2010; see also Linde 2010) or prevent shops and restaurants catering to visitors from displacing other businesses. Ultimately, however, the district government is not in a position to tackle the roots of the challenges it find itself confronted with. What district representatives certainly achieved was to give higher visibility to the issue: especially the ‘Help, the tourists are coming!’ event received a great deal of attention in the media and the district’s officials have regularly engaged in city-wide discussions to advocate for policy changes. Their critique concerns both the Senate’s action as well as its inaction. They argue that the Senate follows an exclusively growth-oriented approach to tourism, chide it for acting negligently – or failing to act altogether – concerning negative externalities surrounding tourism’s growth, and pressure it to move towards a ‘new model driven by ‘sustainable’ goals and principles’. Tourism, rather than being a priority for the Senate, has according to their opinion yet to receive the political attention it deserves, as the Senate has not as yet addressed tourism as a management and planning issue (Linde 2010).

This view is also shared by representatives of the tourist industry. Some of them confirm that the overhaul of tourism promotion in the 1990s has led to a fundamental misunderstanding concerning the respective roles and responsibilities of the public and private sector. It has contributed to a situation in which they are wrongly targeted and blamed for things they are not responsible for, not having the resources nor the competences to carry out proper tourism management and planning. As one employee of Visit Berlin stated during the above-mentioned community meeting, ‘(The organized tourist industry’s) task is to attract visitors, but it is still mainly the responsibility of the local government to plan for and manage tourist impacts.’ Some industry representatives have also understood that tourism development, if too successful, may result in externalities which might ultimately negatively impact tourism’s resource base and the future prospects of Berlin as a destination. Burkhard Kieker, since 2009 CEO of Visit Berlin, has, for example, at times been relatively outspoken about problems associated with tourism’s growth, albeit not so much because of a concern over the integrity of the city and its neighbourhoods or its inherent social costs. Rather, as Kieker once explained in an almost Marxist terminology to the left-leaning newspaper Die Tageszeitung (Rada 2010), he was concerned that too much ‘capitalist exploitation pressure’ might jeopardize some of the city’s main competitive advantages as a destination, in particular Berlin’s famous subculture of temporary music clubs and bars, as well as its more general creative and alternative ‘flair’. Likewise, an understanding took hold in the late 2000s and early 2010s that failing to address nuisance problems and residents’ concerns might ultimately fall back on Berlin as a destination. A draft version of the city’s latest tourism conceptual document (SenWTF 2011) included extensive references to issues such as overcrowding or late-night disturbances leading to conflicts between visitors and residents, and to the need to address them. Many of these references did not make it into the final version of the document, however, reportedly scrapped by government officials who sought to keep the issue out of the election campaign that took place in the autumn of 2011.

On the other hand, the organized tourist industry has repeatedly sought to downplay the degree and extent to which tourism poses a problem by suggesting that many of the perceived issues and conflicts surrounding tourism are owed to the city’s ‘catch-up effect’ after reunification. ‘Paris and London have had hundreds of years to get used to their many visitors. We’ve only had 20 so far,’ Kieker stated in an interview (Duvernoy 2012), suggesting that more time may be needed for its residents to ‘adapt’ to Berlin’s new role as a major tourist destination and come to terms with processes that would, according to him, be considered ‘normal’ in other cities (see the analysis of Paris in this volume), e.g. gentrification (Richter and Anker 2014).

Tourism politics in Berlin: on policy lacunae, conflicts and contradictions

The interpretation of processes like gentrification as ‘normal’ obviously does not sit well with many residents and community groups. Simultaneously serving as cause, context and consequence of the city’s rise to prominence as a visitor destination, gentrification has for many years been one of the most salient and contested trends affecting Berlin. Mobilizations against tourism clearly have to be seen against the background of wider struggles and conflicts surrounding the changing socio-spatial landscape of the city and its social and cultural implications, as well as the state’s complicity in the ongoing gentrification of Berlin’s inner city, soaring housing prices as well as growing socio-economic inequality (Holm 2011, 2014). Over the past years, these struggles increasingly impacted policy-making processes. New rent-control legislation has come into force in 2015 (Russell 2015), previously phased-out public housing programmes were restarted and the city-state, since 2011 governed again by a coalition of Social and Christian Democrats, has vowed to undertake a range of other measures to tackle what is now recognized as a fully-fledged housing crisis.

As regards tourism, policy changes have all in all been marginal, however. In 2013 the city government passed a law to regulate the Wild West of vacation rentals but whether it is effective or not remains under debate (Aulich 2015). Apart from this, the Senate sticks firmly to the position that conflicts surrounding tourism have been blown out of proportion and that there are no significant problems to be solved. Referring to a survey carried out in 2013 which apparently revealed that 87 per cent of Berlin’s inhabitants would not feel disturbed by tourism’s impacts, a Senate report to the Berlin Parliament on the matter concluded that ‘the bottom line is that there are (only) few disturbances, mainly in relation to individual sites, that are perceived as negative by local residents’ (SenWiTechForsch 2014: 2). What the report does not mention is that the number of residents who responded that tourism negatively impacts their lives is two to three time higher in areas particularly affected by tourism growth: in Kreuzberg, roughly ‘a third of local residents complain about noisy party tourists’ as the title of one article put it (Fahrun 2014). Leaving the question of the poll’s merit aside,8 it is noteworthy that one of the main policy recommendations proposed by the Senate as a result in the above-mentioned report was the need to raise inhabitants’ awareness of the ‘economic significance of tourism’ by means of ‘inward marketing’. Part of Visit Berlin’s marketing budget (about €300,000 annually) was consequently earmarked in 2014 for campaigns directed at local residents. Instead of only selling Berlin to tourists, Visit Berlin now also increasingly engages in selling tourism to Berliners. Among other things it set up a website (https://du-hier-in.berlin) to enable residents to provide feedback, comments or inputs concerning tourism in Berlin and has begun to organize ‘citizen workshops’ to develop ideas to improve tourism in Berlin. Significantly, however, the workshops were, at most, semi-public in nature. In addition, until the time of writing (June–October 2015) few concrete results have resulted from them – except perhaps to provide grist to the mill of those who deride such efforts as little more than legitimation exercises.

Representatives of the organized tourist industry, however, know that not all challenges they find themselves confronted with are simply matters of ‘perception’ and can be glossed over by improved public relations. Indeed, they have in recent years more than once also advocated for changes on the ground, e.g. as previously mentioned, in the struggle against vacation rentals, in debates surrounding the swelling number of pub crawl tours and beer bike operators, or in the controversies about the shallow commerce that surrounds sobering sites of memory like the Holocaust Memorial or the former Cold War border crossing at Checkpoint Charlie. Amid signs of frustration about the slow pace of progress on mitigating these and related issues, there is also a concern that a recent shift in economic policy towards a strengthening of Berlin’s high-tech and knowledge-intensive industries will make it even more difficult to convince the Senate to seriously engage with tourism. As one informant put it in 2014:

(Politicians) pride themselves with tourism’s success, but especially in recent years this hasn’t translated into much as far as resources are concerned. [. . .] We don’t need to be convinced that a need for management and planning exists but to them (rather than being a political priority) tourism is more of a cash cow that regularly produces handsome profits but requires little attention.

In cases where the current well-being or future economic prospects of tourism are at stake, it thus seems that the organized tourist industry does not necessarily stand in the way of more planning and, if necessary, of more regulation to address existing problems associated with tourism and prevent future ones from occurring. However, what I referred to as a re-politicization of tourism has also expanded the debate beyond issues of management and governance. Tourism development is increasingly ‘seen’ and discussed as what it is: fundamentally political. This means that distributive concerns and issues of power are raised, and that the prioritization of economic considerations over environmental and social ones that characterizes tourism policy are called into question. Tourism is increasingly recognized as embedded in a broader political economy, and as encompassing much more than the discourse of tourism as an ‘industry’ (and its narrow conceptualizations of the tourism phenomenon) suggests (Higgins-Desbiolles 2006: 1192).

The recent struggles surrounding tourism have consequently exposed two lacunae in the way tourism has been approached in Berlin’s political arena: first, tourism has almost exclusively been dealt with as an economic sector. Responsibilities for tourism are subsumed within the economic development department or, as discussed, outsourced to the tourism industry itself, and there was until recently very little understanding of tourism beyond its role as an economic sector. The cultural, environmental, social and political implications of the scapes and flows caused by visitors and people ‘on the move’ were for a long time barely addressed. Efforts to approach tourism more holistically and develop policy frameworks that are more reflective and sensitive to the features unique to host communities, to include those who are visited into relevant decision-making processes and enable them to reap more of the benefits tourism may bring have been minimal. Second, (policy) debates, if any, revolved until recently almost exclusively around tourists staying in hotels and formal accommodation, while other forms of travel behaviour were rarely addressed, although they too play a significant role in the ongoing reconfiguration of city space and city life. Tourists visiting friends and relatives, daytrippers, as well as a vast number of other transient city users that, by definition, are tourists too even if they are not easily recognized as such (Novy 2010; see the introduction to this volume) were for a long time only of peripheral concern to policy-makers and local officials. This is in part due to the fact that the organized tourist industry is dominated by the hotel and convention sectors, which means that it is their knowledge and expertise that shaped the direction of the field. The discussed lacunae indicate that a discrepancy exists between the rhetoric surrounding tourism as a policy field and what is being implemented in practice. Policy-makers may still describe tourism as their priority, but the reality is more complex, contradictory and inchoate than that.

Figure 3.3 ‘Berlin loves you’. Signs of ‘touristification’ close to Checkpoint Charlie in Berlin’s city centre, 2013.

Source: Thiemo van Assendelft, Mooibeeld.nl.

Conclusion

This chapter addressed the frequently asserted prioritization of tourism as a policy field in contemporary cities and argued that in the case of Berlin tourism is perhaps better characterized as, paradoxically, both a political priority and afterthought. Tourism promotion clearly has become a defining feature of Berlin’s entrepreneurial development politics, regardless of the political party in power, and the quest for tourism growth has exerted a strong influence on current urban and economic development practice and thinking. In light of the enormous economic relevance of tourism for the city, the political attention and resources devoted to tourism should, at the same time, also not be overstated. The city-state’s real engagement with tourism is replete with lacunae and contradictions, and the significance of tourism beyond its economic consequences was for a long time barely considered. Depoliticized and largely outsourced to the tourism industry, tourism as a policy field in its own right remained in an under-developed state: local authorities’ inaction with regard to addressing tourism-related issues was arguably at least as important in contributing to the profound reconfiguration of city space and city life through tourism as their interventions. The described re-politicization of tourism has changed this picture somewhat. Protests and public discontent pushed the Senate into a debate about tourism’s ambiguous and unevenly distributed impacts, and forced it to address at least some negative externalities associated with tourism’s growth, such as the uncontrolled proliferation of vacation rentals.

The debate over tourism’s impacts, however, will likely not go away anytime soon, especially given the projected growth of tourism in the coming years. And why should it? Tourism in Berlin emerged as a bone of contention for all sorts of reasons, and some of these reasons certainly may appear more ‘reasonable’ than others. This does not change the fact, however, that the present mode of development deserves to be debated and contested. It has been neither equitable nor sustainable – as the growing talk about a need to protect tourism from ruining itself confirms. If Berlin’s recent history is any indication, it will require more pressure and more mobilizations ‘from below’ for this to change.