Just as growth in the tourism sector has been hailed as a solution to urban restructuring challenges such as post-industrial and post-socialist transformations in cities of the global North, so too has it been prescribed as a remedy for cities debilitated by violent conflict. Planners and policy-makers consider investment in tourism to be a fast, reliable means of regenerating damaged cityscapes and repairing war-torn economies. Tourism forms a fundamental component of reconstruction plans in Beirut, Sarajevo, Kigali, Nicosia, Cape Town and many other ‘post-conflict’ cities worldwide. In 2011 and 2013, the annual conferences of an international organization dedicated to promoting knowledge transfer among conflict-affected cities, the Forum for Cities in Transition, even featured ‘Cultural Tourism as an Economic Driver’ and ‘Tourism Potential of a Divided City’ as central panel discussions.

Tourism policies shape much more than visitor numbers. As discussed in the introduction to this volume, urban tourism alters social and spatial patterns of the city: delineating new neighbourhoods, changing centre/periphery relations, and generating (or exacerbating) socio-spatial polarization. Moreover, through its discursive and representational re-imaging practices, tourism transforms conceptions and understandings of place (Selwyn 1996; Urry 1990). In the conflict or ‘post-conflict’1 city, such changes map onto the divisions and hardships caused by the hostilities. This chapter examines Belfast, Northern Ireland as a case study in order to analyse how the politics of tourism development intersect with the politics of ethnic conflict in deeply divided cities with histories of violent conflict.

This chapter first analyses tourism development in Belfast from the beginning of the peace process in the mid-1980s, and examines its main socio-political ramifications. It then shows how communities excluded from the benefits of tourism-led regeneration and revenue have developed an alternative tourism offer to protest against their omission from the ‘New Belfast’ vision created and marketed by city leaders. Belfast’s tourism debate differs from many cities in that faith in tourism’s curative properties remains widespread, even among those it most negatively impacts. Local tourism protests do not challenge the prioritization of tourism as a development strategy or its deleterious effects. Instead, protests dispute who gets to shape the city’s tourism offer and who shall benefit from any related economic and political gains. Alternative tourism provision has become a means of securing economic benefits for deprived communities and demanding recognition for cultural traditions and narratives stamped out or elided in official discourses. This alternative tourism industry, however, has itself created tensions, spurring competition between the city’s Protestant and Catholic communities and exacerbating cultural identity contests.2 Rather than constituting a separate, technocratic sphere of urban enterprise, tourism in Belfast has become, I will argue, a new terrain and mechanism for ethnonationalist struggles.

Tourism policy development in Belfast

The legacy of conflict

Belfast is the epicentre of an enduring ethnonationalist conflict, whose roots stretch back to the arrival of Protestant settlers in the predominantly Catholic Ireland in the 1600s. The modern conflict is rooted in the Irish Home Rule movement and the 1921 partitioning of the island into the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland, the latter of which remained in the United Kingdom. Following decades of institutionalized discrimination against the Catholic community within Northern Ireland, disputes about whether the region should remain in the UK or join Ireland took the form of an armed struggle commonly referred to as ‘the Troubles’ (1969–98). The conflict was officially settled in 1998 by the Belfast Agreement, a political accord which created power-sharing mechanisms based on consociational principles and instituted equality measures across a range of policy areas.

Although violence has dramatically decreased since the height of the Troubles, conflict is by no means a thing of the past. Mixing in upper- and middle-class communities is increasing, but Catholic and Protestant communities still lead predominantly separate lives, living in segregated neighbourhoods, attending separate schools and marrying within their own ethnic group (McKeown 2013; Nolan 2014). Individual and collective identities based on ethnicity remain highly salient, and group identities are still constructed in terms of opposition and antagonism (Cairns 2010). Particularly in working-class communities, a ‘conflict ethos’ (Bar-tal 2000) continues to pervade social identity, communal relations and group goals. Outgroup members are viewed with mistrust and communities still prefer to live separated by physical security barriers, the so-called ‘peace walls’ (Jarman 2008). Violence and rioting, in particular in areas at the interface between Catholic and Protestant communities, remain a common occurrence, particularly in the summer parading months.

Over the course of this dispute, points of contention between the two communities have fluctuated in response to political events, broader structural shifts and changing societal attitudes (Ruane and Todd 1996). The once fundamental questions of governance structure and constitutional status have waned, and the conflict today has been reframed around issues of equality, balanced socio-economic opportunities, cultural parity of esteem and transitional justice. The flag protests, which saw over three months of violent and non-violent demonstrations in response to the removal of the Union Jack from Belfast City hall in December 2012 and early 2013, indicates the continued importance of cultural identity recognition and symbols in the region. This issue, coupled with problems of entrenched socio-economic deprivation, plays directly into tourism debates and protests.

‘Confidently moving on’: official tourism development in ‘post-conflict’ Belfast

Prior to the outbreak of the Troubles, Northern Ireland was a popular holiday destination, cherished for its impressive natural landscape and attractive seaside resorts (Boyd 2013). Unsurprisingly, tourism declined drastically during the conflict, with numbers falling in direct correlation to periods of violence receiving substantial media attention (Wilson 1993). Even long after the major episodes of violence had ceased, negative perceptions continued to deter tourists (Boyd 2013).

Policy-makers began strategizing Belfast’s comeback long before the conflict was settled. Heartened by the prospects of stability portended by the 1985 Anglo-Irish Agreement, the Belfast Development Office, the Belfast City Council and the Department of the Environment partnered with private interests to construct a ‘New Belfast’ that would appeal to tourists and investors (Nagle 2010; Needham 1998; Neill 1993). However, as McCabe (2013) argues, Northern Ireland had no real hope for significant amounts of foreign direct investment (FDI) and tourism remained the region’s best chance for economic recovery. Early regeneration efforts focused on the blighted city centre, which had been debilitated by the IRA’s bombing campaign as well as the British government’s securitization measures. The revitalization of Belfast’s central district was designed as a ‘heart transplant’ that would expand outward to revive the wider city (Neill 1993). The council introduced grants to refurbish facades and set up floodlights to showcase ‘architectural masterpieces’ and ‘hide wrinkles’ (Needham 1998: 176). A new shopping centre was built on the city’s high street, whose unshuttered glass facade intentionally symbolized optimism in the peace process (ibid.: 171). Waterfront Hall (begun 1993), the similarly vitreous convention centre erected along the Laganside waterfront, was the city’s first serious bid for tourists: fully aware of the obstacle posed by Belfast’s negative reputation, the City Council initially targeted markets of ‘compulsory tourists’, those who would be required to come to the city for events such as conventions and other business matters. These developments marked the beginnings of a transformation of the city centre and the waterfront into spatial showcases to spur the confidence of potential investors (Figure 8.1). These polished areas likewise shielded guests from the unpleasant realities found in the outlying residential estates, where the environment was still marked with paramilitary murals, watchtowers, barricades and other material manifestations of hostilities. City marketing reinforced the divide, with Belfast’s working-class districts literally cut off of the city’s tourism map.

The push for tourists continued throughout the peace process in the 1990s, and today tourism development has become entrenched as a first order of business in plans, policy papers and strategic documents across a swath of government departments. Development of the local industry is led by the Northern Ireland Tourism Board (NITB), the Belfast City Council (BCC) and the Belfast Visitor and Convention Bureau (BVCB), a destination marketing organization founded immediately after the Belfast Agreement. However, provisions for tourism development are also found in the strategic plans for a number of government departments, e.g. the Planning Service of Northern Ireland (Pl.SNI), the Department of Enterprise, Trade and Investment (DETI), the Department of Culture, Arts and Leisure (DCAL), the Department of Regional Development (DRD) and the Department for Social Development (DSD). Collectively, these departments have directed a two-and-a-half decade makeover of the city centre into a lively commercial district with multiple shopping malls, active high streets and a thriving arts and cultural quarter. The city’s largest undertaking has been the regeneration of Queen’s Island into the ‘Titanic Quarter’, a 185-acre multi-use district branded after the famous liner constructed onsite. Anchoring the district is Titanic Belfast, ‘the world’s largest Titanic-themed visitor attraction’, earmarked by the NITB as one of their five signature projects which they hope will attract 150,000 out-of-state visitors a year.

Since the 1980s, Belfast’s physical refashioning has been accompanied by a persuasive re-imaging campaign aimed at combating deleterious perceptions of the city. While acknowledging curiosity in the conflict, both the NITB and the BCC avoid mentioning the Troubles in their marketing materials for fear that it will deter more visitors than it might attract. Instead, the NITB has focused on a normalizing presentation, highlighting benign attractions such as scenery, outdoor activities and shopping (Wilson 1993). The city’s first attempt to engage with local history was ‘Titanic Belfast’, a city-wide branding strategy that sought to distract from the city’s conflict history by presenting a ‘selected and authorized past’ (Short 2006: 121). Glossing over the institutionalized anti-Catholic sectarianism of these industrial sectors, state agencies use Belfast’s legacy as a manufacturing and shipbuilding powerhouse to present an industrious, resilient and prosperous city (see also Neill et al. 2013). In addition, visitor guides from the past five years have tested out a number of new images: Music City, Literary Belfast, City of Quarters and City of Festivals, all of which showcase the Renaissance ethos of the Northern Ireland tourism identity ‘confidently moving on’ (NITB 2010), while of the Belfast brand ‘a unique history and a future full of promise have come to create a city bursting with energy and optimism’ (BCC and NITB 2011: 3).

Since 1998, Belfast’s tourism numbers and profits have grown steadily. From 1999 to 2012, the number of annual visitors to the capital grew by over 500 per cent, from 1.5 million to 7.6 million – peaking at 9.3 million in 2009 (BCC 2000; BCC 2012). Annual tourism spending has increased from £114 million to £416 million (ibid.); including both direct and indirect expenditure, the total contribution to the city’s economy was £524 million in 2012 (BCC 2012). However, although these numbers represent significant growth, Belfast’s tourism numbers remain much lower than similarly sized European cities and tourism flows are considerably smaller and less international than other cities in this volume. Seventy per cent of visitors came only for a day trip and only roughly 10 per cent travelled from outside Northern Ireland or the Republic of Ireland (ibid.).3 Indisputable, however, is how radically international perceptions of the city have changed. Belfast has received numerous accolades in industry press, and consistently appears on top-ten destination lists, all of which are quick to highlight the city’s comeback. Lonely Planet, for example, proclaimed that ‘once lumped with Beirut, Baghdad and Bosnia as one of the four “Bs” for travelers to avoid, Belfast has pulled off a remarkable transformation from bombs-and-bullets pariah to a hip-hotels-and-hedonism party town’ (Davenport and Berkmoes 2012: 551).

Figure 8.2 Belfast’s neighbourhoods, August 2015.

Source: Author, based on OpenStreet map. CC BY-SA ©OpenStreetMap contributors.

Tourism as a tool of conflict transformation?

From their onset, these regeneration strategies were jointly conceived as conflict management tactics. Politicians used the prospect of an economic ‘peace dividend’ to encourage paramilitary disarmament, arguing that the cessation of violence would be met with financial rewards and communal prosperity brought about by increased tourism and inward investment (Murtagh and Keaveny 2006; Nagle 2010; O’Hearn 2008). O’Hearn (2008) argues that this prospect of a peace dividend – made more attractive by the economic boom brought about by FDI in the Republic of Ireland in the 1990s – was an influential factor in decision of the Irish Republican Army (IRA) decision to announce a 1994 ceasefire. In addition, politicians hoped that a remade, neoliberal Belfast would engender the cultivation of non-sectarian identities based on personal interest and expressed primarily through consumerist and/or entrepreneurial practices. Nagle (2010: 37) states:

By supporting indigenous free-market entrepreneurs to produce wealth through tourism, this would reduce the polarizing strategies of ethno-national leaders seeking to foment interethnic discord. By encouraging individualism and wealth creation facilitated by tourism, locals would no longer be encumbered by their affiliations to the respective ethnic ‘tribes’.

Spatially, this would take place in the ‘neutral’ consumerist districts of the city centre. It was also hoped that new branding strategies would increase civic pride and the salience of superordinate identities (Northover 2010).

Despite these intentions, Belfast’s rapid and radical transformation has provoked socio-political tensions, both exacerbating old problems and instigating new ones. In addition to the strengthening of segregation patterns, the city now faces the new polarization of the city between a thriving centre and wilting working-class districts – socio-economically deprived areas where the majority of the fighting took place and the potential for recurrent conflict still lies (Shirlow and Murtagh 2006; Murtagh and Keaveny 2006). The concentration of new enterprise in the city centre has prevented tourism revenue from reaching working-class neighbourhoods and has thereby reinforced centre/periphery divisions. High price points have placed the new attractions and commercial offerings of the city centre outside the reach of working-class communities (Neill 1993, 2007; Bairner 2003). In addition, few have found jobs in the new service sector, as these jobs either require educational levels or skill sets that the unemployed do not possess, or the jobs are difficult to reach given the city’s disjointed layout and poor public transit (Shirlow and Shuttleworth 1999). Communities protest that they have seen nothing of the promised ‘peace dividend’, and people have grown increasingly resentful of the polarization of the city, which sees them further barricaded from the prospering city centre and trapped in ‘sink estates’ (Murtagh and Keaveny 2006: 188) characterized by poverty, chronic unemployment and societal alienation. Nor do working-class communities see themselves represented in the narratives and images of the new cosmopolitan Belfast. Spatial, economic, symbolic and psychological boundaries have therefore combined to create a profound cleavage between what O’Dowd and Komarova term ‘Consumerist Belfast’ and ‘Troubles Belfast’ (O’Dowd and Komarova 2011: 2016).

Community leaders interpret the imbalanced promotion of tourism and the uneven distribution of its benefits as indicative of state indifference and negligence. They see the exclusion of their group narratives and cultural traditions as a failure of the government to offer recognition and support cultural parity of esteem. This dissatisfaction with the performance of state functions is deeply problematic in societies such as Northern Ireland, where the very legitimacy of the state remains tenuous. Growing class divisions, moreover, are intensifying sectarian divisions. Rather than framing their problems as a class issue common to both parties, Belfast’s working-classes tend to blame their economic difficulties on outgroup favouritism (O’Hearn 2008). The Catholic community attributes social deprivation and immobility to the legacy of institutionalized anti-Catholic discrimination by the Protestant ethnocratic state. Protestants, in turn, frame the hardships of their communities in light of the Catholic community’s growing financial and political influence. On both sides then, socio-economic exclusion has stimulated feelings of victimization and sectarianism. As Baker (2014) states, ‘if there is one thing that can be said for sectarianism, it gives meaning to one’s life and it is free at the point of entry.’ Boredom and resentment stemming from disenfranchisement can provoke interface violence and rioting; moreover, unemployed youth left behind by the new economy can become ‘easy prey’ for recruiting paramilitaries (Murtagh and Keaveney 2006: 187; Nolan 2014). The economic growth that was supposed to undermine ethnic tension has become a driver of the old conflict in a new form.

Challenges to official tourism policy through alternative forms of tourism development

The growth of political tourism: protesting the official image of the New Belfast

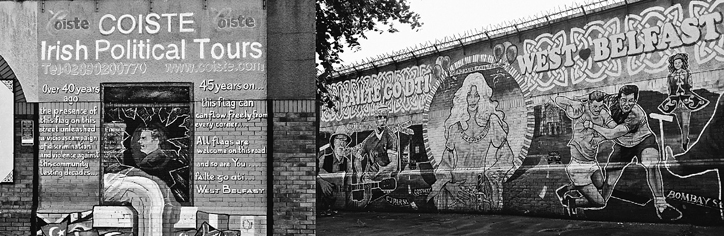

An alternative tourism industry first developed in nationalist West Belfast, where already during the Troubles ‘political tourists’ were coming to learn about the conflict and to show solidarity by participating in parades and demonstrations. Curious to see the sites of conflict known to them through news reports and films, more conventional tourists began trickling into the area following the 1994 ceasefire. Groups from schools, prisoner services, NGOs, political organizations and research institutes also arrived to tour the area and meet individuals involved in the conflict and the peace process. West Belfast locals quickly jumped on this interest and began creating products and services catering to these new visitors. Sites and artefacts related to the Troubles, such as graves, political murals, watchtowers and sites of clashes, were framed as attractions and interpreted through bus and taxi tours, maps and guidebooks and other touristic ‘markers’ (MacCannell 1999). These attractions and services formed the basis of a tourism sub-industry, concentrated along the Falls Road in West Belfast and referred to as ‘political tourism’ (Figure 8.3, left) – or, for those wishing to disparage the practice, ‘Troubles tourism.’

Although some saw the potential for profit, this form of tourism provision was more a political than an economic enterprise. Many involved were community workers, political activists, politicians, even former prisoners and ex-combatants, nationalists who saw tourism development as a means of securing international support for their political cause (Nagle 2010). The internationalization of republicanism in Northern Ireland was a political tactic long used by Sinn Fein, the IRA, and the wider nationalist community (Miller 2010). Thanks in part to the British broadcasting ban, nationalists were particularly adept at finding creative means of disseminating messages abroad. Tourism development, the very nature of which entails the repackaging and circulation of select images and narratives (MacCannell 1999), was a natural forum for the dissemination of state-silenced discourses. Artists painted a factory wall at the entrance to West Belfast with murals celebrating the Republican cause and linking it with nationalist movements elsewhere in the world. The ‘Solidarity Wall’, as it has come to be known, is now the area’s most iconic sight. Black taxi drivers, many of whom came from a political or paramilitary background, began offering tours, where they would provide nationalist commentary on the conflict and seek political sympathizers. Sinn Fein opened their headquarters on the Falls Road as an information and souvenir shop, selling a host of materials related to Irish nationalism. Thus, in its early form, West Belfast tourism constituted a form of political protest against British direct rule and Northern Ireland’s position in the United Kingdom.

In the late 1990s and 2000s, West Belfast’s tourism industry expanded, and a wider array of agents (including private entrepreneurs, political associations, cultural groups and community organizations) became involved in its execution. In 1998, tourism development was partially integrated into the statutory system when a local tourism bureau, Fáilte Feirste Thiar (FFT), was inaugurated and nestled under the West Belfast Area Partnership, a community-level organization sponsored by the DSD. However, the relationship between the FFT and Belfast’s main tourism departments – the BCC, the NITB and the BVCB – has not always been harmonious, as the different agencies have mismatched ideas about the role of political tourism in Belfast’s regeneration.

Neighbourhood tourism has similarly diversified in its motivations and products. Political sites remain a major draw, but have been augmented by services and products based on Irish heritage and culture (Figure 8.3, right). As Sinn Fein’s position has shifted from dissent to active participation in governance (Tonge 2006), and as issues of cultural identity have moved to the centre of Northern Ireland’s political stage, the promotion of Irish cultural heritage has become an increasingly central part of Sinn Fein’s political project (Nic Craith 2003). Since 2003, the party has supported a community-led initiative to rebrand West Belfast as a Gaeltacht Quarter, a cultural district based on the Irish language and traditions. The Gaeltacht Quarter Board has increased Irish language signage in the area, commissioned murals celebrating Irish heritage, and facilitated the refurbishment of Cultúrlann McAdam Ó Fiaich, a multi-use space featuring Irish language classes, Irish music and theatre performances, and a tourism information point for West Belfast. Such initiatives, although pursued for multiple motivations, seek to legitimize the Irish cultural identity in Northern Ireland.

Figure 8.3 Political and cultural tourism in West Belfast. Mural advertising political walking tour and mural promoting Irish cultural heritage, June 2015.

Source: left: Author; right: Claire Colomb.

In addition, increasing importance is being placed on tourism as a tool to combat socio-economic deprivation, by creating jobs, spurring urban renewal and attracting further investment. The idea for the Gaeltacht Quarter, for instance, originated from a task force charged with ‘bringing forward recommendations aimed at reducing poverty and unemployment’ (White and Simpson 2002: 7). Although the hope is in part that the Quarter will bring cultural recognition and educational funding, as one board member declared – pointing out that the four wards included in the initiative are among the most deprived areas in Northern Ireland – ‘the Gaeltacht Quarter is about wealth accumulation.’4

Contentions between district tourism and state agencies

Although tourism in West Belfast has expanded since the 1990s, it still lags significantly behind the rest of the city.5 Problematically for local tourism providers, the majority who do come tend to do so as part of a guided bus tour, quickly photographing the murals and peace lines and returning to the city centre without patronizing local businesses.6 Locals have even attacked tour buses. One reason such tourism continues to predominate is that the district lacks basic infrastructure, such as hotels or sit-in eateries, that would encourage guests to linger or more deeply explore the area. Moreover, safety assurance remains a hurdle; although some visitors are attracted by the neighbourhood’s conflict history, and some are even enthralled by its dangerous feel, most find the ‘roughness’ of the area off-putting and are scared to enter unaccompanied (Tourism Development International 2001). Community tourism officers have struggled to overcome this image problem within the past few years, mainly by publishing information booklets, maps, brochures and websites framing West Belfast as a safe, desirable tourist destination. Their efforts, however, are impeded by the NITB’s and the BVCB’s policy of not actively promoting tourism in the area, leaving West Belfast to appear as a frontier, enter-at-your-own-risk destination.

Those working in West Belfast’s tourism sector attribute the limited success of their endeavours to the unwillingness of the state to fund services or infrastructure and to include West Belfast in promotional material. Community leaders, district councillors and party MPs pontificate about the disproportionate amount of public investment allocated to regeneration in the city centre, particularly in the Titanic Quarter, which many consider a massive over-expenditure to build premises doomed to fail. Questions of representation are also contentious, as community members see the state’s refusal to help combat West Belfast’s image problem as crucial to its own perpetuation. In response to a tourist publication highlighting the yet-to-be-built Titanic Quarter, but excluding West Belfast, a columnist for the Andersontown News wrote, ‘It was a throwback to the days when Vasco de Gama, Columbus, and Galileo explored the world, “civilizing” territories which had previously been marked on the map as unexplored or “Here be dragons”’(Ó Liatháin 2003).

State inaction is combated through multiple, simultaneous strategies. At one end of the spectrum is a ‘go-it-alone’ approach: tourism developers trudge forward, building structure and services with any and all available resources, funding initiatives themselves (even through door-to-door collections) and often coming up with innovative schemes that require little initial investment. For example, FFT headed a creative initiative to turn West Belfast into a Eurozone, getting area shopkeepers to accept the currency in an effort to attract Republic and mainland tourists (Andersontown News, 21 May 2005, p. 16). The area’s biggest draw is the murals and locals have continued to paint new ones in an effort to create attractions and brand the neighbourhood. Murals are even used to advertise tourism products and services.

Developers position their work as the most recent episode in a long history of Catholic self-sufficiency, citing the community’s past self-provision of housing and infrastructure in the face of government neglect and antipathy. Even the advertising for the Black Cab tours emphasizes that the taxis are the legacy of a self-provided transport system designed when city buses stopped servicing West Belfast (Taxi Trax 2015). Whether consciously or not, this attitude manifests in spatial and discursive forms that reinforce the geographic split between West Belfast and the rest of the city (see also McDowell 2008). For all of their talk about integrating West Belfast with the rest of the city, whether as ‘West Belfast, site of the Troubles’ or ‘The Gaeltacht Quarter’, the Falls Road is in fact marketed as a distinct space at odds with greater Belfast.

DIY development has its limitations, however, and developers are aware that their visions for West Belfast will not materialize without public investment. Sinn Fein councillors therefore fight for increased funding from both the city council and the National Assembly. Leaders of other organizations responsible for tourism continue to put pressure on government departments through letter writing and lobbying. Another strategy has been to find funding piecemeal from other sources. The Gaeltacht Quarter Board has been particularly adept at this, applying to the BCC’s Renewing the Routes arterial route regeneration programme for money for Irish language signage, to the Arts Council and Foras na Gaeilge (the all-island council for Irish Language) for funds for a public sculpture celebrating the Irish language, and to DCAL and DSD for the refurbishment of the cultural centre An Chultúrlann. Groups are also attempting to circumvent state constraints by seeking investment from international organizations such as the European Union or the International Fund for Ireland. Widening the field necessitates the mobilization of discourse, i.e. the ability to frame tourism as a driver for whatever the application calls for: culture, equality, employment, regeneration, even – as explained in detail below – social reconciliation.

Intercommunal competition7

However stymied the Catholic community may see their tourism ventures, the Protestant community views these initiatives as resounding successes, and many feel threatened by the sympathy and clout these efforts have brought to the nationalist side. The proliferation of nationalist narratives and symbols through tourism has been read by some as a symbol of the Catholic community’s increasing power and, by extension, evidence of diminishing Protestant influence. Unionist politicians fight funding for political tourism. When Sinn Fein councillor Paul Maskey proposed that DETI support political tourism as a means of assisting deprived neighbourhoods, Unionist politicians dismissed his proposal as an attempt to push Republican propaganda and argued that political tourism would prove detrimental to the attraction of inward investment. This opposition not only shot down Maskey’s proposed amendment, but the Unionists also successfully passed a counter-amendment removing all mention of political tourism and decreeing that DETI should ‘seek to promote Northern Ireland in a positive manner’ (Northern Ireland Assembly 2008; see also Nagle 2010).

Seeking to claim their share of the perceived tourism benefits, in the mid-2000s, working-class Protestants in the neighbourhoods of East Belfast, the Shankill and later Sandy Row began constructing their own tourism offer (Figure 8.4). Expressing anxiety about exclusion as well as defamation, one Protestant tourism officer says, ‘There is a need for a Protestant story to be told. Not a very positive Protestant story is being told at the moment’ (personal communication, 10 April 2011). Less focused on the Troubles, tourism in these areas has focused on cultural traditions and historical events important to the Protestant community, such as the Loyal Orders, Ulster-Scots, the signing of the Ulster Covenant and the Battle of the Somme.

As working-class communities compete against the city centre for visitors and revenue, this ‘district’ or ‘community tourism’, as it is sometimes known, has become a playing field for intercommunal competition over resources as well as over structural and symbolic power. Most evident is the role of tourism as an arena of symbolic contest (Harrison 1995), in which groups endeavour to proliferate their own symbols and/or denigrate the outgroup symbols as a means of accumulating social and political capital. Irish cultural festivals are met with calls for showcases of Ulster-Scots music and dance. The Orangefest parades become a counterpart to St Patrick’s Day festivities. Competition also exists for the ‘correct’ retelling of the conflict narrative, a project which finds its expression primarily in competing Protestant and Catholic guided tours (McDowell 2008; Wiedenhoft Murphy 2010; Nagle 2010).

In this tug of war, the state has come to play the role of legitimizing force, with the distribution of money interpreted as a decree of authorization and approval. The scarcity of public funds available to support tourism ventures leads to perpetual wrangling over resource allocation, with each group claiming preferential treatment for the other. When unionist DUP’s Nelson McCauseland blocked an amendment supporting the Gaeltacht Quarter initiative, Sinn Fein’s Eoin Ó Broin responded, ‘The Gaeltacht Quarter would provide jobs and attract tourists to the city. Clearly these parties cannot contemplate anything that supports the development of the Irish language in the city, and the decision was purely sectarian’ (Andersontown News, 5 December 2003, p. 2). Upon the launch of the Progressive Unionist Party’s manifesto, which included calls for a unionist ‘Orange Quarter’, party member Ken Wilkinson said, ‘At present, everything red, white and blue [unionist] is sectarian and everything green, white and gold [nationalist] is culture’ (Connolly 2011). Community newspapers, such as the (Catholic) Andersontown News and the (Protestant) Shankill Mirror, frequently run exposés regarding the disproportionate allotment of funds alongside editorials linking these numbers to sectarian discrimination.

Given the hearsay involved, it is impossible to accurately determine the degree of influence that sectarianism or group favouritism plays in resource allocation. However, it can be assumed that politicians fight for initiatives that benefit their constituents while blocking initiatives that would anger them. The success of community tourism initiatives is therefore linked to the political sympathies of relevant department heads. For instance, money from the Integrated Development Fund allocated for the Shankill tourism was delayed for years, before a unionist minister pushed the money through to delivery. Similarly, the Gaeltacht Board complained that McCauseland was blocking support for the Gaeltacht Quarter while he was head of DCAL, the lead government agency for the project. Regardless of the factuality of this claim, as soon as a Sinn Fein councillor became department head, she signed a charter of full support (Northern Ireland Executive 2013).

Cooperation and mitigation

Paradoxically, while tourism has sparked conflict, it has also provided institutional and dialogic space for unprecedented levels of intercommunal cooperation. In particular, the more community workers of disparate backgrounds have come to regard tourism as a vehicle of economic development, the more they have worked collectively. Members of the West Belfast Partnership Board, for instance, have shared grant writing tips with less-experienced officers working in Protestant communities, acting on the belief that improving district tourism in one area will benefit all socio-economically deprived communities in Belfast. Certain moments are therefore evident of a solidarity based on collective exclusion.

The commitment of the BCC and the Northern Ireland Office to promoting ‘good relations’ and ‘shared space’ means that initiatives supporting interaction between or benefits across communities are more likely to receive financing than projects engaging only one community. Many funding proposals therefore purposely foreground cross-communal components, seeking support for joint mural projects, marketing initiatives, service provision, etc. This effort occurs in spite of the fact that many involved are not yet interested in, or prepared for, cross-communal work. Combining tourism with cross-communal work also enables organizations to access both local and international funding streams intended for conflict transformation activities. Coiste na n-iarchimí, an organization of former Republican prisoners offering Republican walking tours of the Falls Road since 2003, has used European PEACE money to develop joint tours with EPIC, the organization of former Loyalist prisoners.

Tourism has also promoted the mitigation of contentious symbols. In order to increase support for the Gaeltacht Quarter, for instance, the project’ board has gone to great lengths to depoliticize the Irish language. Given the strong association of Irish with the Republican struggle (O’Reilly 1997), the board was aware that state agencies would hesitate to support the regeneration initiative. In order to increase buy-in for the Quarter, the board has actively worked to disassociate the language from Republicanism, and to reposition the language as a shared cultural resource and as such, one capable of uniting the two communities and promoting reconciliation. To this end, the board has stressed prominent Protestant Irish speakers and the role of Protestants in the language’s twentieth-century revival in its marketing materials, exhibitions and press releases, and has helped establish Irish classes in Protestant neighbourhoods.

These processes of competition and cooperation are occurring concurrently. Moments and patterns of cooperation are increasing, but contestation and competition have by no means disappeared. Even within collaborative projects, conflict continues: an initiative to create a joint tourism map of the Falls Road and the Shankill has faced numerous delays due to disagreement about content and language use. Likewise, some Protestants see the Gaeltacht Quarter Board’s overtures to the Protestant community as insincere ploys for money, aimed at furthering the Catholic community alone.

Conclusion: whose story is the ‘Belfast Story’?

The BCC’s 2003 strategy document, Cultural Tourism: Developing Belfast’s Opportunity, concedes ‘Troubles Tourism – Belfast needs to come to terms with this,’ adding that ‘formalisation and contextualisation and better presentation might help’ (BCC 2003: 46). This statement indicates the city council’s coming to terms with political and community tourism, and their intent to repackage it in the best possible light, i.e. as non-sectarian.

Indeed, a tentative willingness to incorporate district tourism into official promotional materials is evident. Murals and political tours appear on the pages of the city’s website and printed visitor guides with increasing frequency. However, these sites and services are still mostly sidelined, often buried in laundry lists of more acceptable attractions, e.g. ‘from traditional music sessions to political murals, from Milltown and City Cemeteries to Clonard Monastery and St Peter’s Cathedral, West Belfast certainly has lots to see’ (BVCB 2011: 15). Community tourism based on cultural heritage has been more warmly received. Since 2007, the BVCB has included the Gaeltacht Quarter as an official city quarter in their annual visitor guides, and the council is experimenting with the branding theme ‘Belfast City of Quarters’ as a means of providing representational space for the city’s multiple – and ever-splintering – narratives and identities (Carden 2012).8 It is unsurprising that city officials are more open to culture than politics – even if in Belfast the two are often one and the same – and it is to be expected that communities will continue to mitigate their narratives under the rubric of cultural heritage in order to gain state approval and resources. The most recent tourism strategy, the 2010–14 Belfast Integrated Tourism Framework, gives a small indication of the direction of future convergence between community and state tourism. Overall, the strategy recommendations remain strongly focused on the city centre. However, one of six ‘visionary drivers’ is the ‘Belfast Story’, the theme under which the NITB and the BCC have selected to incorporate the city’s conflict and community history and described as follows (BCC and NITB 2011: 23):

The Belfast Story: This is a thread which should run through all that is done to develop tourism – to reflect the brand values of the city. It should embrace: Heritage – the story of the city through the ages – its people, its buildings, its conflicts; Tradition & Community – the legacy of the city’s recent history needs to be accessible to visitors. It should include the character and characters of Belfast and cross-cutting our cultural offering. This is where we belong, edgy, different, cool, etc. This also presents an opportunity to embrace our culture and identity.

Here, conflict history is grouped under one heading along with culture, identity, heritage, tradition and community. The language used is vague, and it is impossible to determine any concrete plans from the text. The action plan ambiguously states, ‘Identify innovative ways to communicate the Belfast Story across the city and at key strategic locations’ (ibid.). The framework does suggest that ‘conflict resolution can be a focus’ (ibid.), suggesting the possibility of a future effort to incorporate community tourism’s conflict narrative with the city council’s Renaissance narrative. Such a turn would support recent moves made by the government – thus far only in the sphere of international politics – to establish Northern Ireland as a potentially exportable model of conflict resolution.

The Belfast Story might indicate a continuum with regard to the presentation of conflict heritage: the further in time the relevant events have receded, the less state actors are hesitant to engage with a contentious past. On the other hand, the appearance of the Belfast Story in the latest policy document may signify the state’s confidence to address the conflict under an acceptable rubric. Its appearance does indicate that communities’ demands for greater representation are being heard by the council and the tourism board, even if the response to date has been minimal. However, whether representation will grow to significant levels or translate into significant investment is more questionable. Belfast’s tourism growth since 1998 has been remarkable; yet as stated, numbers have dropped in the past two years and the damage done to the city’s reputation and the economy by the flags protest has made politicians wary. For these reasons, state agencies are likely to continue to shy away from community tourism, in spite of the fact that offering support could potentially offset some of the very problems they are trying to hide.

The substantial link with and impact of tourism on Belfast’s ethnic conflict underscores a fundamental issue witnessed pervasively throughout the chapters of this book: whether it is gentrification in Berlin, poverty and exclusion in Rio de Janeiro or structural urban transformation in Prague, tourism is deeply embedded in key socio-spatial processes – and likewise, transforms their manifestations. By extension, protests and challenges to tourism development overlap with other, even seemingly unrelated interests and issues. As this volume has shown, protest against tourism policy can take many different forms. Belfast’s political/district tourism industry exemplifies how tourism itself can serve as a form of protest, in this case against dominant narratives of place identity and urban development (see Luger on Singapore in this volume). However, tourism initiatives pursued in opposition to state visions face strong limitations, and developers must proceed creatively in order to circumvent obstacles arising from a lack of public support. The most successful tactic in Belfast has been the engagement of third-party actors, whether private investors, international funders, non-local journalists or the tourists themselves. International attention forces governments to recognize that there is a compelling demand for new types of tourism which may be economically profitable and socially beneficial. This can lead the state to accept or co-opt such forms of tourism. In the end, tourism development and its contestations unfold across different types of actors (public, private and civil society) and scales (local, national and international), with conflict and cooperation between them occurring not along fixed lines, but changing dynamically as interests and alliances shift.