As an emerging global power, Brazil has recently experienced one of the highest rates of economic growth in the world. Tourism is a key sector of the Brazilian economy, which has also enjoyed a steady growth since the 2008–9 economic crisis (UNWTO 2014). While in 2006 direct employment in the tourism sector reached 1.87 million people, this number rose to 8.5 million jobs in 2014, making Brazil the fifth greatest tourist nation in terms of direct employment (Embratur 2014). In 2013, the World Travel and Tourism Council ranked Brazil sixth in the world tourism economy, identifying it as the nation with the greatest growth potential in terms of tourism (UNWTO 2014). Experts link this tourism boom to the global visibility that mega sporting events like the 2014 FIFA World Cup and the 2016 Olympics afforded Brazil on the world stage. They also cite a stable currency and the pacification of Rio de Janeiro’s favelas among the main reasons behind this increase (Oliveira 2012). Rio de Janeiro is Brazil’s primary tourist attraction and one of the most visited cities in the southern hemisphere (Tavener 2012). It receives more visitors than any other South American city, with an average of 2.82 million international tourists a year (UNWTO 2014). Rio also represented the most popular destination for national visitors in 2012 (Embratur 2014). According to a 2012 World Travel Market Industry Report, almost two-thirds of tourism industry observers believed that Rio de Janeiro would benefit from a tourism boost until and after the 2016 Olympics (WTM 2012).

This chapter details the emergence of a new phenomenon in the Brazilian tourism landscape, that of ‘slum’ or ‘favela tourism’, with a particular focus on the city of Rio de Janeiro, host of the 2014 FIFA World Cup and 2016 Summer Olympics.1 The chapter pays particular attention to the source and nature of conflicts, tensions and resistance movements that have appeared in Rio de Janeiro as favela tourism expands. The development of favela tourism has been at the root of frictions within local communities, especially when those perceived to be the main beneficiaries of tourism are not local residents. Tourism-related investments, which appear to serve outside visitors to the detriment of community members or which threaten people’s quality of life, intimacy, accessibility or security of tenure, are increasingly condemned. Diverse forms of resistance movements to tourism expansion within favela territories are taking form, especially when tourism is imposed without the residents’ consent.

The chapter begins with an overview of the historical rise of ‘poverty tourism’ around the world, contextualising the emergence of this phenomenon and discussing the motivations driving its development. The chapter examines in more detail the emergence of favela tourism in Rio de Janeiro and discusses its drivers, its appeal and the ways in which it is perceived within and outside the favelas. The chapter then presents a typology of different forms of favela tourism, based on different management structures, and examines the relationship between visitors, residents and intermediary agents. The final part of the chapter focuses on the conflicts generated by the growth of favela tourism and details some of the critiques and modes of resistance developed by local residents. The chapter concludes with an early assessment of the impacts and benefits of such a form of tourism, underlining the possibility of future areas of conflicts and resistance related to the growing ‘touristification’ of the favela and suggesting directions for further research.

Slum tourism as a global phenomenon

As one of the world’s fastest growing service industries, tourism is constantly trying to diversify its products and expand into new, increasingly segmented markets. Alternative forms of tourism that go off the beaten track have emerged as part of this segmentation (Lew 2015). They answer a desire for the acquisition of symbolic capital and the search for new modes of distinction (Bourdieu 1979) that help uphold class differentiation and maintain a social distance with mainstream forms of tourism. New trends in global sightseeing are also fed by a growing demand for intense, unconventional or ‘extreme’ experiences, a phenomenon witnessed in the rise of extreme sports and thrill-seeking adventure travel. They respond to a quest for a real, authentic and unique experience that departs from the artificiality of packaged tourism products (Jaguaribe and Hetherington 2006). More than the simple search for authenticity described by Dean MacCannell (1976), these alternative forms of tourism are the product of a fast-growing obsession for reality, for the direct, first-hand experience of the real: what I would call extreme authenticity.

This quest for raw reality and thrilling experiences has given rise to a range of new forms of tourism that take people far from the mainstream to places on the margin. For one, ‘disaster tourism’ (Robb 2009), also termed ‘dark tourism’ (Lennon and Foley 2000), offers so-called reality tours of sites that have acquired a historical and political significance for their association with natural or man-made disasters. This practice is highly controversial, and denounced as a commodification of human tragedy that feeds upon a morbid fascination for pain and suffering (Veissiere 2010; Lisle 2004).

Another controversial form of tourism on the rise is ‘poverty tourism’. Specialists distinguish between volunteer tourism, also known as ‘pro-poor tourism’, which claims a more humanistic, altruistic and educational mission with a participatory approach, and slum tourism, derogatively branded poorism, described as mere sightseeing without the intent of alleviating local conditions and lacking a humanitarian motive (Rolfes 2010; Scheyvens 2013; Steinbrink 2012). Recent years have seen an explosion in the popularity of visits to impoverished areas, starting in the mid-1980s with South African township tours, closely followed by jeep tours of Rio de Janeiro’s favelas (Freire-Medeiros 2008). Today, tour operators take tourists to garbage dumps in Cairo, Delhi’s railway underworld and some of the world’s most notorious slums.

Poorism has been compared to ‘slumming’, a trendy elite pastime practised in nineteenth-century London, Paris and New York, which was driven by a mix of philanthropy, curiosity and voyeuristic titillation (Parker 2003; Koven 2009; Parker 2003). Like faraway colonies, seedy neighbourhoods were seen by artists, intellectuals and parts of the gentry as places of freedom and danger, of missionary altruism and of social, personal and sexual liberation. For Henry James, slumming was a passion driven by a desire to cross opposite universes, from the rich to the poor, the clean to the dirty, the virtuous to the depraved (El-Rayess 2014). Charles Baudelaire also enjoyed mingling with the masses. In Les Fleurs du Mal (2003 [1857]: 93), he writes: ‘In murky corners of old cities, where everything – horror too – is magical, I study, servile to my moods, the odd and charming refuse of humanity.’

For many contemporary experts, poverty tourism falls into what MacCannell (1976) defined as negative sightseeing, and is critiqued as an unethical trivialisation of poverty for socio-voyeuristic or self-promotional motives (Rolfes 2010; Whyte et al. 2010). At the onset, the idea of poverty tourism was thus regarded as highly offensive (Lancaster 2007). The premise was that visits were motivated by a morbid desire, on the part of predominantly bourgeois thrill-seekers, to witness human suffering up close. Poverty tourism was also condemned by critics and academics as a transnational desire for the consumption of Third World poverty, a commodification of power inequality and of human misery (Frenzel et al. 2012; Sellinger and Outterson 2010). Some authors denounce the ‘theme-parkification’ of the slum, repackaged as a product to be consumed by an international clientele (Zeiderman 2006).

The development of favela tourism in Rio de Janeiro: background, drivers and perceptions

Rio de Janeiro’s favelas in historical context

The favela has long been a characteristic feature of the city of Rio de Janeiro and a central part of its urban reality. Resulting from the illegal occupation of hills and marshlands by poor and often black residents in search of affordable housing, favelas came to be viewed as special territories, located on the margin of the formal city (Valladares do Prado 2005). Favelas were feared as a threat to authority, order and stability and their inhabitants despised for refusing to conform to established rules. Defined in radical opposition to the formal city, they were construed as a negatively connoted landscape, associated with illegality, disorder and decline (Perlman 2010). Their residents paid no taxes, received few public services and were deprived of the same civil rights as other Brazilians (Zaluar and Alvito 1998). Having been all but abandoned by the state, these territories began attracting criminal groups, and by the 1990s, many were left to the cruel domination of violent drug gangs and militias.

Throughout most of their history, favelas were desired as an absence in Rio’s urban landscape and subjected to many measures of invisibilisation and silencing, from bulldozing and evictions, widely practised until the 1980s, to more subtle measures of beautification (Valladares do Prado 2005). They did not exist in the formal imaginary and did not appear on official city maps (Johanson 2013). The term favela itself, being too negatively connoted, suffered a similar invisibilisation process, replaced by the euphemistic ‘hill’ (morro) or ‘community’ (communidade). Although the local media continues to depict favelas as places of crime and violence and as the natural habitat of the ‘dangerous classes’, after 118 years of existence, perceptions are changing and the stigma towards Rio’s favelas is waning. Since the late 1990s, public policies have tended towards the recognition of favelas as urban neighbourhoods and favoured their integration into the formal city (Riley et al. 2001). In 2014, one in five residents of Rio de Janeiro lived in a favela (IBGE 2014).

Historical development of favela tourism in Rio de Janeiro

Favelas have long been an object of fascination for visitors to Rio. However, they were generally observed from a safe distance (from the asfalto or street level) as an oddity in the urban landscape. Among the first foreigners who dared enter this forbidden world were social scientists, eager to understand its peculiarities, or members of non-governmental organisations working on poverty alleviation. But tourists also accessed the favela on special occasions, especially to visit samba schools in the weeks before Carnival, as an important part of the Carnival experience. Earliest initiatives at touring the favelas can be traced back to the mid-1970s and were led by NGOs (Rodrigues 2014).

But it would take almost twenty years for the first formal tours of Rio’s favelas to be conducted. During the 1992 United Nations Summit on the Environment, delegates reportedly asked to visit a favela and were taken by jeep to Rocinha, then known as Latin America’s largest slum (Freire-Medeiros 2012). Favela tourism was thus demand-based, and developed in response to the request of curious visitors, even though no formal tourist product was on offer. It was only later that local entrepreneurs and residents, ultimately aided by the government, would capitalise upon this initial interest by multiplying tour offers and developing attractions. While favela tours steadily expanded over time, the phenomenon experienced an unprecedented boom in the years preceding the 2014 World Cup and the 2016 Olympics. This expansion has been attributed to state programmes for the pacification of favelas, initiated in 2008. Preparation for Rio’s mega-events has included the permanent occupation of key settlements by a specially trained police force, with the disarmament and expulsion of drug traffickers and armed militias. The arrival of these Police Pacification Units prompted a series of rapid transformations in the favelas, bringing peace and security to the residents while making them safer for tourism-related activities (Freeman 2012).

Motivations of favela tourists

Paradoxically, part of the attraction of the favela has long rested in its association with violence, idealised in recent feature films (Jaguaribe 2004). The global popularity of Brazilian ‘reality’ movies such as City of God (2002)2 and the use of the favela as a backdrop in mainstream Hollywood films,3 a trend that was branded slumsploitation (Gilligan 2006), has attracted hosts of thrill-seeking visitors. Interest in the favela was also stimulated by its glamorisation in the global mass media, especially as an exotic stage set for music videos by African-American pop stars. First popularised by Michael Jackson in They Don’t Care About Us (1996), directed by Spike Lee, the favela is now featured in videos by Beyoncé Knowles, Alicia Keys and Snoopdog. The favela is also becoming a fashionable site for international art projects, such as the Dutch artists Haas and Hahn’s 2010 favela painting project, or the French artist JR’s 2008 Women are Heroes installation.

Since the turn of the millennium, the favela has acquired a sort of cult status in the global geographical imaginary, where it occupies a unique position as both a hot, fashionable commodity and a trendy trademark (Freire-Medeiros 2008). There are Favela Chic nightclubs in London, Paris, Glasgow, Montreal and Miami (Sterling 2010). Two Brazilian-Italian designers, Umberto and Fernando Campana, have created the favela chair out of rough pieces of plywood (at a price of $5,185). For Tom Philips (2003), the word ‘favela’ now stands as a tropical prefix capable of turning the most diverse products into something exotic. The favela even represents a state of mind, as suggested by a 2005 photo exhibition held in a Paris subway station, titled Favélité. The vast production, reproduction and diffusion of images of the favela testifies to its fetishisation as a ‘cultural object’ that goes beyond Western fascination with the exotic ‘Other’ but suggests a vaster consumption appeal (Zeiderman 2006).

The favela therefore carries a strong evocative power, with multiple connotations, ranging from the strange and mysterious, to the forbidden, amoral and violent all the way to the rickety, haphazard and chaotic. It exerts a secret fascination for outsiders, symbolising the dark, the low, the unknown, onto which the most lurid fantasies can be projected (Steinbrink 2012; Zeiderman 2006). The favela is imagined as a kind of forbidden underworld, the evil twin of formal society, liberated from rigid social norms, propriety and morality, where licentiousness, libidinal freedom, and unbridled depravity can be found (Steinbrink 2013). For anthropologist Bianca Freire-Medeiros (2012), the perception of danger remains one of the favela’s most seductive aspects, attractive not only for its adrenaline rush appeal but also for its capacity to enhance the symbolic capital that can be gained from a visit.

As favela tourism develops, it becomes clear that visitors are driven by a complex host of motives that are often contradictory and difficult to disentangle. While the notion of poverty tourism implies that poverty alone is what is being sought out, the desire to see and experience raw human misery up close is not always the main motive. Visits to neighbourhoods like Harlem (in New York City) or Brazil’s favelas are also driven by curiosity about a different way of life and by the promise of a close encounter with radical forms of alterity. Such motives betray a heroisation of the poor, idealised not for their lack of material wealth, but for their resilience in the struggle against adversity and their capacity to turn oppression into cultural vibrancy. This attraction suggests a conceptualization of poverty as a pure and primitive state, closer to raw human nature, as if material deprivation had made the poor more authentic representatives of mankind and beholders of true values.

My own research suggests that poverty tourism is motivated by a natural attraction for the unknown, doubled with a yearning to experience compassion for the suffering of others. The experience can be at once reassuring in one’s own material comfort while fulfilling a desire for empathy. Visitors are also attracted to these steep hillside communities out of curiosity for the human ingenuity and capacity for survival that is embedded in their self-built environment: the feat of building such elaborate neighbourhoods on precarious land with limited resources and skills is a source of great admiration. It is therefore not so much poverty per se that motivates many visits but the resilience, resourcefulness and determination of a community of hard-working people who managed to carve out an existence for themselves in spite of their difficult circumstances. My research also suggests that part of the favela’s attraction also rests upon the great social capital that can be gained from having ‘been’ to a favela. Just as early researchers and NGO workers gained an aura of respectability for having ‘lived among the poor’, tourists are seeking out similar ‘bragging rights’ that testify to their own courage, altruism and selflessness. Artists who use the favela as the locus of their art projects similarly capitalise upon the sympathy capital that a great social cause can confer. Other travellers, especially those described as ‘anti-tourists’ (Miller and Auyong 1998), may also be motivated by a search for distinction and seek to distantiate themselves from ordinary tourists by sojourning in the favela.

Brazilian perception of favela tourism

Inside Brazil, the notion of favela tourism was met by resistance and opposed by those who still believe in the illegality of these settlements and the necessity of their eradication. Local authorities long condemned the association between favela and tourism, through fear it would tarnish Brazil’s international image. In 1996, the filming of Michael Jackson’s music video was widely opposed by the state, who argued that its display of local poverty could damage the local tourism industry and ruin Rio’s chances to get the 2004 Olympics (Schemo 1996).4 But this attitude is changing, as testified by Rio’s tourism board’s 2010 decision to include Rocinha on its official website as one of the city’s top attractions.

In the favela, attitudes towards tourism vary. Many welcome the practice as an opportunity to replace drug trafficking as an income-generating activity. They believe that tourism will stimulate the development of local businesses and create new jobs. Favela tourism is also widely perceived as a path to change, to promote social inclusion, alter perceptions and reverse stereotypes. Many believe that it is only through first-hand knowledge that outsiders will understand the challenges faced by favelados and overcome the stigma that has isolated them for years. Daily encounters with foreign visitors are also seen as beneficial for the young, helping develop alternative visions of their future.

A survey conducted in 2013 by Catalytic Communities, a Rio de Janeiro-based NGO, demonstrates the potential of direct contact with favela residents in affecting perceptions (Sinek 2013). Based on 750 interviews made in Rio de Janeiro, San Francisco, Brisbane and London, the survey made clear that people who had actually visited a favela held dramatically more positive views of these settlements. The survey also demonstrated how violent and sensationalist representations of the favela in film and the media contributed to their negative image. Among the top keywords used to describe the favela by people who had visited one, words like community, misunderstood and vibrant stood out while for those who only knew of the favela through the media, top key words included dangerous, cramped, poverty, crime and ghetto (Sinek 2013).

Still, many favela residents have reservations towards what is often perceived as an invasive practice. The growing presence of outsiders in the favela’s dense urban fabric can be problematic, since the limited transitional space between the private and the public realms provides few filters for the preservation of intimacy. Ironically, from the residents’ point of view, tourists are seen as a potential source of danger and crime. Many residents expressed reservations towards the idea that their children could run into strangers on the streets of their hitherto isolated community.

Local perception of tourism thus varies greatly depending on who is promoting it, how it is conducted and for whose benefit. The following section provides a panorama of different forms of favela tourism that currently exist in Rio de Janeiro and helps ascertain differences in their acceptation and impacts.

The multiple manifestations of favela tourism: a typology

Initial research conducted between 2009 and 2014 helps trace a portrait of the current state of favela tourism initiatives in Rio de Janeiro, which can be divided into four broad categories: private, for profit initiatives from outside the favela; community-based, non-profit initiatives; local commercial initiatives; and state-led favela tourism. Each category is defined and analysed below to reveal areas of success, friction and resistance.

Private, for profit initiatives from outside the favela

The oldest and still predominant form of favela tourism in Rio de Janeiro is based on professionally conducted tours by private companies, which often have little ties to the community. Packaged tours generally include a visit in jeeps, on motorcycles or on foot, with stops at community centres, crafts markets and scenic lookouts. They are conducted by guides who may or may not be from the favela. Although many companies claim to reinvest part of their profits in community projects, research shows that it is seldom the case (Freire-Medeiros 2012). There now exists a well-established commission-based cooperation between tour operators and local shops and restaurants in the favelas. Each month, up to 3,000 tourists are taken to Rocinha alone, by ten different agencies whose names evoke a range of experiences from an adventure in the urban wilderness to a more authentic, less voyeuristic tour.5 Since the beginning of the pacification process in 2008, the number of competing operators has grown dramatically, with dozens of new tourism agencies seeking to exploit these newly opened territories.

Favela tourism was long dominated by this kind of operation, which favour visits to favelas with easy road access, especially in Rio’s elite South Zones, with great views of the city’s famous landscape. These tours were founded on the premise that foreigners were more interested in ‘having been’ to the favela than in interacting with locals. Long tolerated by local community members, these outside initiatives are increasingly the objects of scorn. Motorised tours are despised because they prevent contact between visitors and residents, especially when tourists stay inside their air-conditioned vehicle for the duration of the visit, without setting foot in the favela. Locals are offended by the attitude of visitors who photograph residents without their consent, like animals in a zoo. They experience a lack of respect, a violation of their privacy and an affront to their dignity. Non-motorised tours are perceived as less intrusive and more respectful, allowing a greater level of interaction. Most residents interviewed believe that tours should be conducted by local guides. They resent the position of cultural authority that outside guides have over the interpretation of their community. They accuse this kind of tour of reproducing stereotypes about the favela rather than helping overcome them. To meet the expectations of international tourists, some private tour operators have been known to purposely take visitors through some of the most derelict parts of favelas and to stage some dramatic encounters to boost the adrenaline content of their visit (Frisch 2012).

Community-based initiatives

A second type of tourism that is quickly developing in Rio de Janeiro is community-based, not-for-profit tourist initiatives. Local groups capitalise upon growing interest for their settlement by developing local attractions, including interpretation centres, open-air museums, eco-trails, belvederes, art projects and cultural events. In the favela complex of Pavão-Pavãozinho-Cantagalo, the Museu de Favela (Favela Museum) was founded in 2008 to promote community development (Moraes 2010). It gained visibility after pacification and the construction of the new elevator in 2010, linking Cantagalo to Ipanema and its main subway station. The open-air museum, which comprises the entire favela, tells the story of the settlement through a series of murals signed by Acme, a local artist. The murals immortalise local heroes and depict the community’s many historical struggles: against water shortages, faulty infrastructure, exclusion and exploitation. More than a mere tourist attraction, the murals serve as instruments of storytelling that help foster community pride, collective identity and shared memory. Tours sometimes include a samba show, drinks and cake from the baking coop, and visits to artist workshops. Considered to be Brazil’s first ‘territorial museum’, the Museu de Favela was an initiative of Rio Arte Popular, a local tourism cooperative founded in 1998. It was funded by the federal Programme for the Acceleration of Growth (PAC) and its Social Insertion Base (BISU) (Moraes 2010). The stated goal of this initiative was to develop community-managed tourism and to attract tourists to the favela without the use of middlemen. Revenues generated by guided tours are used to fund community-training programmes in tourism (Moraes 2010).

Community-based initiatives take various forms. In the twin favelas of Babilonia-Chapéu Mangueira, guides from local tourism cooperatives, Babilonia Coop and Chapéu Tour, take visitors through the jungle on a community-maintained ‘eco-trail’ to the top of the hill for spectacular views and point to the filming locations of Marcel Camus’ award-winning Black Orpheus (1959). In Maré, an indoor museum created in 2005 traces the history of this bayside favela complex through photos and artefacts. While serving the community’s need for collective memory and legitimacy by establishing its long occupation of the site, the museum also addresses an outside audience, invited to shop in its crafts cooperative.

Many residents view these initiatives as opportunities to debunk misrepresentations of their community and to bolster collective self-esteem by showing a more positive side of the favela. Community-led tourism gives residents the chance to ‘speak’ for themselves and to control the way they are represented. By advocating visits on foot, in small groups and with a local guide, encouraging local consumption and limiting unauthorised photography, community-based tourism helps mitigate the perverse asymmetry that exists between the tourist and the object of his gaze. The main impediment for this kind of community-led development is language, as few residents speak foreign tongues. But tourism has stimulated interest in new state programmes for the acquisition of language skills.

Hospitality tourism and local for-profit initiatives

A third form of favela tourism concerns private, for-profit businesses catering to tourists inside the favela. Since the late 1990s, long before pacification, individual entrepreneurs began buying lots or transformed abandoned mansions to accommodate hostels, bars or art galleries. These early pioneers, often foreign expatriates, wanted to benefit from cheap land, great views and proximity to elite beach neighbourhoods, while experiencing another urban reality. They also lacked the deeply rooted prejudice towards the favela that many middle- and upper-class Brazilians harbour. Their businesses cater mainly to members of the backpacker crowd, who cannot afford Rio’s expensive accommodations, often settle for long time periods and are open to different ways of life. Many large mansions abandoned by their owners after drug trafficking drastically reduced their real estate value have been converted into hostels. Located along paved streets, at the transition point between the asfalto (asphalt, i.e. formal city) and the morro (hill, i.e. favela), these affordable accommodations have rendered porous the psychological barrier that long separated these two antagonistic worlds. As foreign tourists began venturing into favelas and consumed locally in small shops and eateries, they helped break down this virtual border, helped change mentalities and contributed to local economic development. Their presence made the favela increasingly safe and accessible for other visitors and paved the way for entrepreneurs, from both within and without the community. Since pacification, many residents have thus converted part of their homes into hostels and small shops, also wishing to benefit from the tourism boom linked to Rio’s mega-events. One example is Favela Inn, a youth hostel managed by a local couple, high up in the hills of Chapéu-Mangueira. A survey of entries left by travellers in their visitors’ book reveals feelings of fear and anxiety at residing in the favela, mixed with excitement at the rare opportunity to live such a truly ‘authentic’ experience. Recurring keywords found in these testimonies include community, typical, real, genuine, authentic, anxiety and danger.

Residents claim not to mind the presence of these establishments but some have reservations about businesses owned by outsiders who seek to benefit from a combination of cheap real estate and exotic appeal. The gradual and rather limited nature of this ongoing transformation has contained some of the negative effects of tourism development seen elsewhere, especially regarding gentrification. However, the recent arrival of larger commercial institutions is more problematic and is causing tensions inside the favelas. Not only do residents fear rising prices and speculation, but they also resent newcomers who profit from a land that long-term residents have developed with their own labour, without contributing their share. Locals fear that their hard won and already overstretched infrastructure will be monopolised by these newcomers. In Vidigal, residents are blaming a new designer hotel for clogging the limited transport system with their wealthy guests, forcing labourers to waste their limited free time waiting for the shuttle that would take them home. Local resentment against this business has taken diverse forms, from graffiti to petty theft, indicating that its presence is not welcome.

State-led favela tourism

A last form of favela tourism in Rio de Janeiro concerns public sector initiatives, as favela tourism is increasingly embraced, funded and even promoted by the state. Undoubtedly related to Rio’s mega-events, this phenomenon marks a radical change in attitude on the part of local authorities and betrays a desire to reassure the world about the safety of Brazilian cities, by enhancing the visibility of the state in long-neglected favelas and improving security and access. State investment in tourism can take the form of individual infrastructure projects, such as cable cars, elevators, and funiculars linking hillside favelas to public transportation networks. They also follow a more comprehensive approach, as in the case of Santa Marta, presented below.

The first and most extensive experiment with state-led favela tourism was Rio Top Tour, a pilot project that sought to help provide guided tours of pacified favelas. The programme was financed by a special fund dedicated to community-based tourism, at the initiative of Brazil’s Ministry of Tourism, Sports and Leisure in 2006 (Rodrigues 2014). The pilot project was inaugurated in 2010, by President Lula himself, as one of his last legacies before leaving office, and lasted until the end of 2012. It aimed to provide alternative sources of employment after the departure of drug trafficking and was to become a model to be replicated in other favelas (Rodrigues 2014). It is in Santa Marta, a favela often used as a testing ground for several state programmes, that the pilot programme was implemented. The favela was selected because of its relatively small size, housing some 5,000 souls; its location in the middle-class neighbourhood of Botafogo at the foot of the Christ the Redemptor statue; and its great visibility and easy access. Santa Marta was the first favela to be pacified in December 2008, and received Rio’s first Police Pacification Unit a few months after the inauguration of the funicular, also a first in the city.

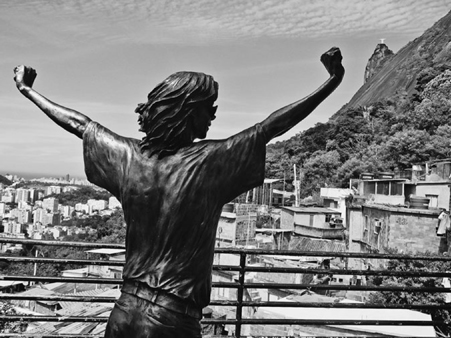

The favela benefited from a great tourism potential, thanks to its privileged views of the Corcovado and close association with global pop star Michael Jackson. As the film location of his 1996 music video, the favela had gained a kind of cult status among Jackson fans. In 2010, a rooftop featured in the video, which had become a popular tourist attraction, was renovated by the state and rebranded Michael Jackson Square. On the first anniversary of his death, a statue of the star was unveiled along with a mural by a close friend of Jackson, world-renowned artist Romero Britto (Figure 10.1). The same year, the favela was blessed with another world-class attraction, with Dutch artists Haas and Hahn’s Favela Painting, covering 34 houses in a stunning kaleidoscopic fresco.

The pilot project included a free technical course in tourism offered at a nearby state college to train local guides. Workshops and micro-loans were made available to those residents wishing to develop tourism-related enterprises. With the participation of residents, 34 points of interest were selected and identified with plaques, in both English and Portuguese. Free bilingual maps featuring points of interest were offered to visitors, who were also given the opportunity to hire a local guide. A total of 60,000 visits were conducted during the two years of the pilot project, with an average of 2,000 per month, 60 per cent of which were from Brazil, thereby debunking the myth that favela tourism was for ‘gringos’ (Rodrigues 2014). All visitors were accompanied. At the end of the pilot project in 2012, newly trained guides from Santa Marta founded their own agency, renamed Rio Favela Tour.

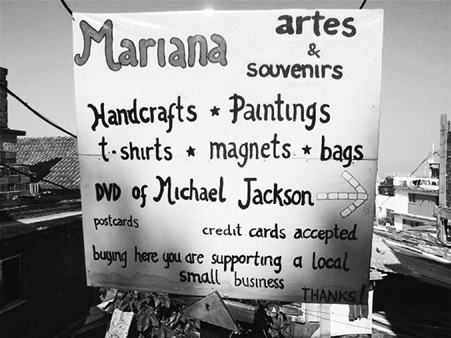

Overall, the project was successful, allowing residents to control how and when their neighbourhood could be toured and creating a few jobs. However, problems are emerging. The existence of an organized agency has hindered independent visits, with tourists complaining of harassment from local guides, who pressure them to take a paying tour even on repeat visits. The multiplication of tourist shops near the favela’s main attractions (Figure 10.2) is giving the area the feel of a ‘tourist trap’. Some visitors disliked being hassled by local vendors and saw their tourist experience as less authentic compared to other, more ‘open’ favelas. This experience poses a dilemma between integration and turning the favela into a regular neighbourhood, and self-segregation by restricting admittance. In its efforts to control the tourist experience and to discourage independent visits, the community has turned itself into a paying attraction, thereby denaturing the experience of the ‘real’ sought by visitors. While this approach may ensure a steady revenue for tour guides, it also gives the favela an exclusive character and can lead to its negative branding as ‘touristified’.

Conflicts and resistance to favela tourism

As it develops, favela tourism has become a source of conflict between residents, entrepreneurs, civic authorities and visitors. More than mere tensions between ‘hosts’ and ‘guests’, these disputes reflect wider struggles over the socio-spatial transformations that are restructuring the urban landscape as the city prepares to host the 2016 Olympics. The main points of friction concern a generalized lack of public consultation in the decision-making process regarding tourism development and project implementation, coupled with a total disregard for community needs or what is often perceived as prioritising tourists over residents. Anger is not only directed at local authorities but also at private actors in the tourism industry. Those without direct ties to tourism resent bearing the cost of its development – in terms of the invasion of privacy, the strain on infrastructure and rising prices – without reaping the benefits.

Residents increasingly see infrastructure improvement and pacification as part of a wider state project to transform the image of the favela for the benefit of outsiders. State interventions are often perceived as a means of displacing the poor to facilitate the reclaiming of valuable territories by private capital. People see state-led tourism in the favelas as part of a civilising process that seeks to tame, regulate and control the favela and make it safe for foreign visitors and investors. In recent years, the most notable tourism-related conflicts have been linked to the construction of transportation infrastructure in Rio’s favelas, especially cable cars, presented by the state as public transportation initiatives but denounced as a misuse of welfare funds to serve tourism.

The cable car wars

In 2012, the first in a series of new favela cable car systems built in the years leading to the coming mega-events was erected in the Complexo do Alemão. The location of this infrastructure clearly responded to a desire, on the part of local authorities, to counter negative perceptions of this particular favela, whose violent invasion by Brazilian armed forces in 2010 had made global news. While some residents welcomed the project, especially those with reduced mobility or living near the five cable car stations, many accused the city of diverting federal funds intended for much needed sanitation, education and road repair (Broudehoux and Legroux 2013). Additionally, people knew that such an expensive, sophisticated, European-made system would never have been built for them alone. Trilingual signage throughout the system, in Portuguese, English and Spanish, supports the theory that, under the pretence of a public service, the cable car was built for tourists (Broudehoux and Legroux 2013). Residents thus deride the infrastructure as an ‘image project’, ill-suited for local mobility needs. They complain that the cable car, which links the five hilltops of the favela complex, is difficult to access for most residents who do not live near those summits. Furthermore, it does not allow for the transport of merchandise. According to 2014 statistics, after an initial boom in ridership due to novelty, resident use fell to a mere 10 per cent. On weekends, up to 60 per cent of users are tourists, local residents having reverted to using moto-taxis and other alternative modes of transport, rather than the inefficient cable car (Broudehoux and Legroux 2013).

It was with the implementation of a second cable car, in Providência, a highly emblematic favela located at the heart of Rio de Janeiro’s old harbour, that more vocal and organised resistance started to emerge. Investments in access roads, cable cars and historical preservation were denounced as serving Porto Maravilha, a vast port revitalization project launched with the Olympic deadline in mind. These projects would require massive demolition and the displacement of up to one-third of Providência’s community. In 2011, a series of well-organized protests were held to save Praça Americo Blum, the favela’s main square, where the cable car station was to be erected. By joining forces with other community groups, protestors increased their leverage against state authorities and succeeded in attracting the attention of local media and international observers. A few victories were made: demolitions were postponed and many tourism-related projects were abandoned, especially the sanitised renovation of Cruzeiro, the favela’s historical district. The controversial cable car could not be stopped, but it would take almost two years after its realisation before it was finally put into operation in July 2014. The great fanfare, media attention and timing of the inauguration, in the middle of the FIFA World Cup, were taken as yet another proof of the touristic motives of the project.

Who benefits from favela tourism?

In spite of growing discontent over tourism-related investments, resistance rarely spills outside the limits of the favela. However, in June 2013, as people all over Brazil held demonstrations to denounce excesses related to mega-events,6 people in Rocinha took to the streets of the upmarket neighbourhood of São Conrado to protest the planned construction of a cable car in their community. They castigated the project as a tourist-oriented white elephant. Protestors also condemned outside tourist agencies for painting a superficial and stereotyped portrait of the community and for pocketing the benefits from favela tours without giving anything back. In July 2013, residents from Santa Marta also marched on the streets of the middle-class area of Botafogo to complain about tourism. They railed against the multiplication of jeep tours, denounced as a violent invasion of their territory. People reviled the promotion of favela tourism by the state and complained of the growing number of visitors flocking to their community.

Resistance to favela tourism was not only aimed at large-scale, state-led initiatives but it was also waged against new businesses, such as recently established hotels and restaurants. Initially perceived as a potential source of employment, these businesses soon became a cause of anxiety for residents, who feared losing what precious little they had gained through hard work and perseverance. Uncertainty was palpable during a series of public debates held in Vidigal in May 2014, organised by the NGO Catalytic Community in collaboration with local community groups. Entrepreneurs who had recently settled in the community were invited to answer questions from residents about their concerns over the rapid transformation of the favela, especially with regard to real-estate speculation. Residents’ testimonies revealed growing suspicion towards these potential new ‘invaders’. The Mirante do Arvrão Hotel built at the top of Vidigal in 2013 was accused of having taken advantage of an elderly couple, who sold their home for R$2,000, without knowing it would be replaced by a million dollar hotel. The new art school built by world-renowned artist Vik Muniz was also charged with exploiting the favela as a source of social capital, gained on the back of poor people. While the school’s manager insisted on the benevolent character of the institution, concerned with the well-being of the community, residents expressed resentment against the arrogance of outsiders who come uninvited and pretend to know their needs. Favelados were obviously tired of being used as a ‘social cause’ by well-intentioned people wanting to feel good about ‘giving back’.

Across Rio, residents have started to realise how their favela is becoming a resource for all sorts of capital gain: not only are outsiders extracting economic capital from new businesses in the form of cheap land and new markets, but the favela is also used as a source of symbolic capital. After academics, researchers, designers and NGOs, artists are taking on philanthropic projects to polish their image in the eye of the global public, a trend that has been called humanitarian or compassion branding (Vestergaard 2008). For locals, tourists are only adding to the lot of intruders who come and help themselves in the favela as if at an open buffet.

In this light, Santa Marta’s unique tourism experience as a state-led tourist project could be seen as a different form of resistance, a resistance to the banalization of the favela as a mass tourist destination, and a refusal to give in to self-help tourism, where outsiders just walk into their neighbourhood as if it were an open house. Paradoxically, maintaining control over access and demanding that paid local guides accompany visitors is beginning to impact the favela’s attractiveness as a tourist product.

Conclusion

This chapter traced a portrait of favela tourism in Rio de Janeiro, a practice still in its infancy and undergoing rapid transformations. Already, over the six-year study period, several changes could be noted. Motivations for visiting favelas are evolving, moving away from stereotypes of crime, violence and the eroticisation of poverty towards a true experience of favela life. The hosting of the World Cup greatly improved knowledge of Rio’s favelas and drastically altered perceptions: many recent visitors ignored the fact that favelas were once forbidden territories. In Brazil, media coverage of the favela is becoming more positive, covering cultural practices and gastronomy as much as violence and crime.

While thorough impact studies of favela tourism still need be conducted, it is possible to evaluate some of the early outcomes of such practices. The chapter suggests that favela tourism is both an opportunity and a threat: it could contribute to these settlements’ integration and economic development as much as it could take away from them. The pressure exerted on local real estate can make favela tourism a promoter of gentrification, splitting up communities and exacerbating socio-spatial segregation. This phenomenon is already visible in several favelas located near the city’s most famous beaches, where a recent rise of more than 400 per cent in house values has triggered the departure of many residents away from the South Zone towards the Northern periphery. The boom in tourism linked to the hosting of mega-events such as the 2014 World Cup and 2016 Olympics is directly responsible for this phenomenon.

On the other hand, the growing attention and increased visibility given to the favela in the global media thanks to tourism development has been beneficial, resulting in a greater level of attention and care towards these settlements on the part of local authorities. In the future, the challenge will be to find a balance in the way favela tourism is conducted, one that will warrant dignity for residents and income generation while limiting its adverse effects.

Overall, the most positive favela tourism initiatives are those that have been conducted in collaboration with local communities, which limit the feeling of intrusion and disturbance, respect their need for privacy and yield clear benefits for the collectivity. Most offensive have been those initiatives imposed without consultation and which appear disrespectful and exploitative to the locals. Low-impact, small-scale, community-led initiatives such as resident-managed eco-trails and crafts cooperatives are successful examples. Other tourist activities, either individual commercial initiatives or state-led infrastructure projects, must be developed in consultation with local groups, include transparent impact assessment studies and propose innovative ways for the favela to benefit from such projects or to compensate residents for perceived losses and nuisances.

Future studies of favela tourism will have to address key questions. Will the favela retain its appeal now that the danger has gone? Will its rising popularity be the source of its demise, as interest for favelas dwindle once they become accessible to mass tourism? Will pacification, integration and gentrification transform the favela’s unique territorial identity, turning it into a working-class neighbourhood with a view? As favela tourism expands and develops, it will also be interesting to see how it impacts local self-representation. Will favelados alter their behaviour to fit outside expectations and meet outsiders’ criteria of authenticity, however staged? Will they ‘perform’ a version of their ‘culture’ for the tourists? Will the continuous expansion of favela tourism fuel more tensions and conflicts over its benefits for favela residents? These questions and many more will have to be investigated in the future to deepen our understanding of this emerging phenomenon.