Urban ‘mega-events’ like the Olympics are frequently used to spur tourism flows and pursue urban development goals in the process. They are defined as events with ‘dramatic character, mass popular appeal and international significance’ (Roche 2000: 1).1 These events stimulate temporary tourist economies, but they may also crowd out other tourism activity as non-event tourists avoid temporarily inflated costs and crowds (Porter and Chin 2012; Zimbalist 2015). For example, the London Olympics attracted 11 million visitors (LOCOG 2012: 32), but the United Kingdom’s international tourist count decreased by 5 per cent during the two months of the Games (ONS 2012). Thus rather than relying only on short-term tourism gains, event promoters highlight the role of mega-events as catalysts for local investment. Usually promoted as offering the potential for ‘legacy’, Olympic investments are said to regenerate communities (Smith 2012), to facilitate social inclusion (van Wynsberghe et al. 2013; Pillay and Bass 2008) and to deliver innovations in sustainable infrastructure (Mol 2010).

However, boosterish claims about the potential for Olympics to produce positive legacies are routinely challenged by researchers from across the political spectrum. Critics note that mega-events are more likely to experience cost overruns than most other types of urban mega-projects (Preuss 2004; Flyvbjerg and Stewart 2012), that evidence of net positive impacts on the regional economy is suspect (Porter and Chin 2012), that long-term and ‘trickle-down’ development effects are often smaller than promised (Pillay and Bass 2008; Zimbalist 2015) and that Olympics are institutionally structured to allocate risk to city governments and profits to sports federations and their business partners (Boykoff 2014b).

Mega-events represent a prominent tool of urban tourism policy and are symptomatic of broader tourism politics in neoliberal urban contexts. Planning for mega-events introduces what I term a ‘democratic displacement’ in the politics of the tourist city, by which debate over urban policy and public finance circumvents the participatory protocols expected of many urban mega-projects. This displacement derives from the timelines required of event planning: decisions made at the early stages of bidding and planning establish path dependencies which displace subsequent deliberation. This is not to say that cities should never host the Olympics nor that Olympic planners intentionally seek to disenfranchise urban residents. There are certainly mega-event development success stories (e.g. in Pillay et al. 2009; Smith 2012), and taxpayers are sometimes willing to pay for the intangible benefits of hosting (Atkinson et al. 2008). Rather, the decision to host an Olympics is often not subjected to the same standards of participatory review and deliberation which are expected of other urban mega-projects, and this ultimately diminishes the legitimacy of and public support for mega-events as a tool of (tourism-led) urban development.

In this chapter I analyse the urban politics of mega-events by tracing the process of democratic displacement to its source: the bidding process. After reviewing the relationship between mega-events and urban tourism, I empirically assess the extent of democratic displacements and the impact of anti-bid social movements. I argue that mega-events and other ‘temporary’ event-led initiatives should not be viewed as ad hoc instances in urban politics, but rather as embedded in long-term agendas by particular stakeholder groups in the city (cf. Lauermann 2015). The politics of the event happen long before it; in this sense bids are a key site and moment in the politics of the Olympic city. I demonstrate this with a study of social movements which protest Olympic bids, documenting how democratic displacements are accomplished in urban politics.2 The chapter also seeks to evaluate how they might be avoided.

The chapter contributes to debates about the ‘post-political’ dimension of urban governance in the case of the tourist city. Critical analysts view contemporary urban governance as a form of techno-managerialism which leaves space for debate over the ‘how’ of governance but forecloses discussion over the ‘why’ (Dikeç 2007; Swyngedouw 2009; Davidson and Iveson 2015). In Olympic cities there is significant debate over managing and mitigating Olympic projects, but as I demonstrate in the following discussion, debates over if and why a city should host the event are less common. This latter form of contestation is often limited to a temporary ‘moment of movements’ (Boykoff 2014a: 26) in which activists mobilize in response to the impacts of Olympic planning after the project is underway. However, a number of recent movements have formed to contest Olympic bids at earlier planning stages. These anti-bid movements have caused significant disruption within the Olympic industry. For instance, in the most recent round of bidding for the 2022 Winter Olympics, anti-bid protests derailed plans for the Games in Krakow, Munich, Stockholm, St Moritz (Switzerland) and Oslo, leaving only two cities (Almaty and Beijing) in the applicant pool.3

Mega-events and the tourist city

Previous scholarship highlights three relationships between the tourist city and mega-events like the Olympics. All are concerned with the impact of using a temporary event to increase visitor flows and catalysing local development. Debates over post-event ‘legacy’ are central to each approach. First, there is a contentious debate over the economic impact of temporary tourist events (see reviews in Preuss 2004: ch. 6; Smith 2012: ch. 8). Event tourism can generate a temporary increase in demand for local services (Chalip 2004; O’Brien 2006), and mega-events can produce a ‘signal effect’ which improves consumer and employer confidence (Rose and Spiegel 2010). Willingness-to-pay surveys have shown that taxpayers value the intangible benefits of a mega-event (e.g. community pride, global exposure) but not always enough to match the costs of hosting (Atkinson et al. 2008; Ahlfeldt and Maennig 2012). Economic impact assessments are hotly contested: most rely on input-output models which fail to account for the fact that by definition a ‘mega’-event shifts the parameters of the regional economy – and thus the multipliers which should be used in an econometric model (Porter and Chin 2012; Zimbalist 2015). Specifically, claims that mega-events generate net positive economic impacts often neglect to account for crowding out effects (Olympic tourists displacing other tourists) and substitution effects (tourists spend more on Olympic activities but less at other local businesses) (Baade and Matheson 2004; Whitson and Horne 2006; Maennig and Richter 2012). Ex post studies based on more reliable data (like tax receipts) are much less optimistic than ex ante impact studies, which are often commissioned by bid promoters (Dwyer et al. 2005; Baumann and Matheson 2013). Scholars from across the political spectrum have demonstrated instead a pervasive over-optimism in bidders’ cost-benefit projections (Flyvbjerg and Stewart 2012; Boykoff 2014b).

Second, there is a debate on post-event ‘legacy tourism’ and the broader role of Olympics in place marketing (see reviews in Getz 2008; Gold and Gold 2008). Enhanced destination brands have been described as intangible but significant tourism legacies, especially when iconic venues becomes tourist attractions in their own right (Chalip and Costa 2005; Gratton and Preuss 2008). Others signal to the geopolitical role that this place branding portends, as mega-events are used not only for marketing cities but also to re-brand ambitious national states (Zhang and Zhao 2009; Black and Peacock 2011; Müller 2011). This tourism legacy sometimes extends outside the city, as various ‘sport for development’ programmes use revenues for national and international development programmes (Pillay and Bass 2008; Levermore 2011).

Third, there is a debate over how mega-events and other tourist spectacles are used in urban politics, especially the politics of the neoliberal/entrepreneurial city. These commentators debate the role of mega-events in market-led development strategies, especially when public funds are used to subsidise private-sector projects (Boykoff 2014b; Zimbalist 2015). Analysts drawing on urban regime theory (Cochrane et al. 1996; Burbank et al. 2002) have pointed to the role of tourism in legitimating and maintaining a city’s governance elite; a ‘mega-event strategy’ uses global media exposure to promote local projects (Andranovich et al. 2001). A related argument points to the role of tourist spectacles in urban growth politics: tourist events enable ‘selectively transnationalized’ growth coalitions which use global relationships and expertise to promote local growth politics (Surborg et al. 2008: 327), e.g. by rhetorically linking real-estate projects to broader imperatives for globalizing cultural industries in the city (Hiller 2000a; Hall 2006).

Protest and contestation in the Olympic city

While these three approaches present compelling narratives about the (positive and negative) impacts of mega-events on the city, relatively little has been written about protest in the Olympic city (though note studies like Lenskyj 2008; Cottrell and Nelson 2011; Boykoff 2014a). Contestation is typically framed as a debate over the scope and limits of legacy narratives: boosters highlight the impact of Olympic projects while critics deconstruct it and challenge the claims of the boosters. Thus contestation is often relatively narrow in scope: debating how to ameliorate impacts or improve project outcomes, rather than broader questions about opportunity costs and whether the Olympics should be pursued at all. This is due in part to democratic displacements at the bid stage, hampering public debate and oversight at later planning stages.

Within the urban politics and social movements literatures, Olympic protest is typically framed in two ways. The first describes mega-events as temporary but exceptionally problematic projects in urban politics. They are interpreted as producing ‘states of exception’ (Agamben 2005) in which typical standards of governance legitimacy are suspended. The state of exception induces a temporary legal and institutional climate which diverges from conventional forms of urban politics. Boykoff (2014b) concisely summarises this approach, describing Olympic urban politics as a form of ‘celebration capitalism’, the ‘affable cousin’ of disaster capitalism (Klein 2007): ‘Both occur in states of exception and both allow plucky politicos and their corporate cohorts to push policies they wouldn’t dream of during normal political times’ (Boykoff 2014b: 3). However, ‘rather than disaster we get spectacle . . . the Olympics become an alibi for forging spaces of political-economic exception where authoritarian tendencies can more freely express themselves’ (ibid.: 11).

In this framing, mega-events are viewed as interventions in urban politics which induce temporary relaxations of the normal rule of law, to the benefit of corporate sponsors and real-estate investors. Such states of exception temporarily allow for tax-free profits (Louw 2012), for extraordinary security laws and the use of military-grade weapons for policing (Giulianotti and Klauser 2011), or for the displacement of disadvantaged residents (Greene 2003; CHORE 2007). These ‘temporary’ states of exception can have long-term impacts as they permanently displace residents, redistribute public funds or create path dependencies in urban policy (e.g. around the militarization of policing practices).

Given the ‘mega’ dimensions of Olympic projects, impacts are widespread and protests are common. But protest against states of exception tends to be reactive rather than proactive. In a rare comparative study of anti-Olympic activism, Boykoff (2014a: 26) explores anti-Olympic social movements in Vancouver, London and Sochi and describes this temporality as a ‘moment of movements’ during which ‘extant activist groups come together using the Olympics as their fight-back focal point’. This type of momentary protest is temporally circumscribed, occurring when planning produces negative impacts rather than at earlier phases when the entire project could be contested. It is also highly localised, organised to contest specific impacts of an individual Olympics (e.g. securitisation in London, slum demolitions in Rio de Janeiro) rather than against the mega-events industry as it migrates from one city to the next.

The second framing describes mega-events as bound up in neoliberal urban politics. That is, the Olympics are discussed as one part of broader governance strategies which favour market-led approaches to governing the city. In such forms of governance, bids for mega-events are interpreted as part of a ‘mega-event strategy’ for local development, in which even unsuccessful bids for the Games are ‘enough to warrant media exposure and provide some claim to Olympic symbols to unify disparate stakeholders, however transitory these claims might be’ (Andranovich et al. 2001: 127). Thus mega-events are viewed as a global-local strategy for profit and political legitimation: they are planned by ‘selectively transnationalized’ growth coalitions whose ‘primary function is to balance the traditional political power of locally-based growth coalitions with the need to respond to extra-territorial actors and coalitions – a growth machine diaspora’ (Surborg et al. 2008: 324).

In this second framing, contestation is analysed as part of protest against neoliberal governance tactics like austerity or municipal speculation. For mega-event planning, urban decision-makers often turn to global networks of expertise by recruiting consultants (Lauermann 2014a; Müller 2014), sending municipal staff to learn from peers in other cities (Cook and Ward 2011; González 2011) and directly adopting the technical standards requested by the sports federations (Eick 2010; Klauser 2011; Kassens-Noor 2013). Much of the scholarship on those processes critiques the top-down relationships reproduced between cities and the international sponsor/federation/consultant networks. Forms of contestations and activism targeting these relationships have denounced corruption and lack of transparency in the governance of sport federations (Girginov 2010; Horne and Whannel 2012), although the networks of consultants and real-estate firms which undergird those relationships receive less attention (Lauermann 2014a; Müller 2014).

One common argument in both lines of interpretation is that Olympic bidding displaces or circumvents public debate over urban policy. bid proposals are contingent on winning a contract and are by definition speculative, but if a bid succeeds the logistical challenge of delivering the project on time creates substantial political pressure to solidify the proposal quickly (and foreclose future debate). Hiller (2000b: 193, original emphasis) summarises this displacement:

Since the foundation of the plan is laid in the bid phase, there is always a tendency for urban residents to see the exercise as only hypothetical and, therefore, not to take it seriously. When citizens do take it seriously, it can be countered that this is only an early plan. But the problem is that, when and if the bid is successful, something conceived by others as only a conceptual idea takes on a life of its own as the plan.

But it is perhaps too simple to blame hapless citizens; this abrupt transition from contingent proposal to contractual obligation produces ‘celebratory states of exception’ (Boykoff 2014b: 11). Writing on this transition from a contingent plan to a contractually obligated ‘delivery imperative’ in the case of the London 2012 Games, for instance, Raco (2014: 191) documents how

responsibility for policy has been handed over to project managers, with the delivery of the Games converted into a technical programme of action adhering to specifications and decisions outlined in the contractual phase of the development, and therefore subject primarily to technical challenges and adaptations, rather than significant policy objections. It represents a clear example of how decisions become frozen at a particular point in time to facilitate the development process.

The consequence is that contestation over Olympic planning has historically focused on ameliorating impacts and improving legacies after a city commits to hosting (see discussions in Lenskyj 2008; Boykoff 2014a). But Olympic impacts are only felt years after plans are finalised and contracts are signed. Olympic boosters officially launch their bids to host the Games 8–10 years before the event, and some unofficially start earlier by bidding for the Olympics multiple times and hosting a variety of smaller events along the way (Lauermann 2015). Thus democratic debate over the role of mega-events in urban development can be displaced as contract negotiations are completed long before local movements mobilize to contest the project.

Olympic bids and the democratic displacement

Both of these critical interpretations – protesting states of exception, or contesting the neoliberalisation of urban politics – converge around a shared understanding of the political dynamics of mega-events. Both signal the use of mega-events as a means for depoliticising urban governance. states of exception take place at the final stages of a long-term political process, in which questions about the opportunity cost of hosting – and about whether an Olympics should be pursued at all – are already moot. Similarly, the post-political dimensions of neoliberal urban politics are well documented (see reviews in Kiel 2009; MacLeod 2011), and mega-events can be read as a tool for facilitating market-led forms of urban development policies (Raco 2014). In short, both interpretations discuss the politics of mega-events as symptomatic of broader post-political trends in urban politics.

The notion of the ‘post-political’ or the ‘post-democratic’ has emerged as a prominent framework for interpreting the contemporary city (see reviews in Dikeç 2007; Swyngedouw 2009; Davidson and Iveson 2015), often as an outgrowth of entrepreneurial governance practices (MacLeod 2011). This concept refers to a form of governance which allows, and even encourages, participatory forms of decision-making within an established governance paradigm, but avoids and excludes systemically disruptive conversations about alternative paradigms (Rancière 1999, 2006; Mouffe 2005). That is, there is a place for participation in discussions over ‘how’ the city is governed within an existing paradigm (e.g. how do we ameliorate Olympic impacts or increase legacies?) but not normative debates over ‘why’ the city should be governed as such (e.g. why should the city host an Olympics in the first place?). As Davidson and Iveson (2015: 546) put it:

The presence of contestation and/or difference does not mean that it is incorrect to characterise urban governance as ‘post-political’ or ‘post-democratic’. In any given city there may indeed be scope for debate about which policies might help that city to become more competitive, more global, more sustainable, more secure, and so on. But challenging the underlying necessity and legitimacy of these visions is far more difficult.

Olympic urban politics are a case in point: contestation often develops over how the city might be governed (ameliorate the negatives, add to legacy funds, compensate the displaced, etc.). But there is less conversation about the ‘underlying necessity and legitimacy’ (ibid.) of event-led governance models. This displacement is institutional and temporal. The institutional displacement is a familiar one in neoliberal urbanism: profit-oriented transnational networks are able to plug into local urban politics and provide a set of business-friendly practices for delivering the Games (Hall 2006; Whitson and Horne 2006; Surborg et al. 2008; Eick 2011; van Wynsberghe et al. 2013). While they are promoted as apolitical and pragmatic, these practices can also ‘manipulate state actors as partners, pushing us toward economics rooted in so-called public-private partnerships . . . [which are] lopsided: the public pays and the private profits’ (Boykoff 2014b: 3). More specifically, the local state (usually a municipal government) pays and consultants, sponsors, sports federations and real-estate firms profit.

The temporal displacement occurs when temporary interventions induce states of exception in urban politics. A state of exception implies that it is too late to contest the origins of that exception: the fundamental political question as to whether a city should host the Olympics at all. The early stages of planning, especially the bidding process, are the origins of a state of exception. For example, the IOC’s former director of marketing (Payne 2006: 191) went so far as to praise this as a form of top-down planning led by transnational experts. He suggested imposing a ‘strict brand discipline’ at the bid phase:

The danger, otherwise, is that the local politics get in the way. A city that is one of several on a shortlist is altogether easier to deal with than the same city once it is confirmed as the next Olympic host.

After a bid has been approved, the moment for that normative debate is quickly supplanted by project management issues, subcontracts and a ‘delivery imperative’ (Raco 2014). Thus broader normative debates over the opportunity costs of the mega-event are displaced by project deadlines and relatively narrow debates over impact and legacy.

The analysis which follows shows that mega-events are an important site for analysing the urban post-political condition. This offers broader insight into the role of urban post-politics in tourist cities. The post-political (despite its ‘post’ prefix) is not so much an end state where ‘politics’ no longer exists. Rather it refers to an ongoing process of separation – often but not always led by policy-making elites (Rancière 2006; Swyngedouw 2009) – between the ‘how’ of governance and contesting the ‘why’. In the case of Olympic cities this is a process by which decision-making about the city’s future mega-event is relegated to technical debates over how to manage or mitigate the impacts of the Games, rather than normative debates over if and why hosting is a wise policy agenda. In the discussion which follows, I show how this displacement process occurs, and how urban social movements have sought to contest it.

Olympic urban politics: contesting the bid

While the impacts of a mega-event are most likely to elicit protest, the core institutional inequalities which produce those impacts are designed earlier during the bid phase. Bids are the site and moment when normative dimensions of urban development visions might be debated. They define who has a voice in how policy will incorporate new priorities, how investments will be financed, how urban space will be planned and, most fundamentally, if a city will host the Games at all.

Most Olympic bid corporations claim some form of local political legitimacy when representing ‘their’ city. Yet their representativeness can be questionable. A sample of polls on Olympic bids over the last 20 years highlights this trend.4 Since the early 1990s most bid corporations have surveyed public opinion on the bid. Bidders have significant incentives to overstate public support for their projects, and the level of support claimed in some cities is high enough to be suspect (on average, bidders claimed 72.7 per cent of residents in their cities were in support). Cities in non-democratic states present particularly suspect examples: for instance, the original Beijing bid (written in 1993 for a 2000 Olympics) claimed that 92.6 per cent of citizens strongly supported the Olympic project, and noted ominously that ‘neither now nor in the future will there emerge in Beijing organisations opposing Beijing’s bid’ (Beijing 2000 1993: vol. 1, p. 24).

As a counterweight to this tendency the IOC has funded separate surveys in each bid city since 2000 (finding levels of support which are, on average, 4.1 percentage points lower than the bid corporation surveys) (IOC 2000). But authoritarian outliers and questionable survey techniques distract from the broader limits to public participation in Olympic bids: out of the 81 sampled bids (for Summer and Winter Games between 2000 and 2020), only 12 were subject to a formal referendum and 56 bids claimed to have no knowledge of any local opposition at all. While bidders’ claims of ‘no discernible opposition’ (Moscow, 2012), ‘no organized opposition’ (London, 2012; PyeongChang, 2018) or ‘no major movement against’ (Tokyo, 2020) seem strategically myopic, this also signals to the relatively limited scale and visibility of anti-bid protest.

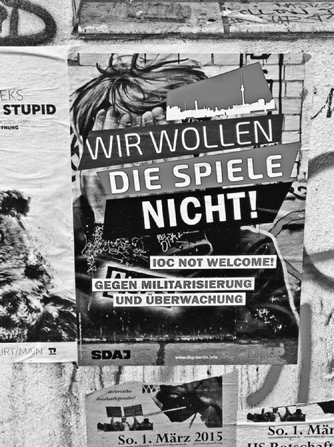

Contesting a bid requires activists and critics to be proactive. With one exception (Denver), no city has withdrawn from an Olympic contract after winning a bid.5 Post-award contestation lacks an institutional mechanism for demanding concessions from Olympic planners: recalling the previously quoted IOC marketing expert, bidding negotiations are a way to make decisions ‘before local politics get in the way’ (Payne 2006: 191). The host city government is contractually obligated to provide the capital investments detailed in the bid, because the bid document forms the legal basis for a city’s contract with the IOC. Recalling Raco (2014: 191), ‘decisions become frozen at a particular point in time to facilitate the development process.’ In contrast, anti-bid politics often involve proactive, normative contestation: highlighting the opportunity costs of an Olympics (Figure 11.1) and contesting whether the Olympics should be pursued at all (Figure 11.2). As one anti-bid activist (protesting the Boston bid for the 2024 Games) put it:

We wouldn’t have been working on this as volunteers . . . if it were just about some of the factors in the deals, or about getting to the table for negotiating and then going away [after we were heard]. So I think we should be very clear about one thing: we are not ‘maybe Boston’. We are ‘no Boston’ and we have no intention of changing that.6

There are relatively few historical examples of large-scale anti-bid protests. But these protests often had the effect of slowing or stopping the bid outright. Voters successfully demanded a referendum on a Quebec bid to host the 2002 Winter Games (the bid failed before the referendum occurred) and voters in Berne rejected a 2010 Olympic bid (Bramham 2002). An ‘Anti-Olympia-Komitee’ organized a movement against the Berlin 2000 bid, damaging the brand value of the bid and prompting opposition parties in local and national government to launch corruption investigations (Colomb 2012: ch. 4). A ‘Bread not Circuses’ social movement failed to prevent Toronto’s 1996 and 2008 bids for the Games, but it did produce enough negative publicity to undermine the bid corporations’ proposals (Lenskyj 2008). A movement in Paris had a similar negative publicity effect on bids for the 2008 and 2012 Games (Issert and Lunzenfichter 2006). Recent movements have achieved more success in halting Olympic bids. For example, in the competition to host the 2022 Winter Games, local activists were successful in halting bids – sometimes by successfully demanding and winning referendums – in Krakow, Munich, Stockholm, St Moritz (Switzerland) and Oslo (Clarey 2014).

But stopping a bid outright is not necessarily the only or optimal outcome of contesting an Olympic project. Rather, contesting bids is a way to call for accountability and transparency from Olympic planners. For example, anti-bid protests partially inspired an institutional review at the IOC, summarised in the Olympic Agenda 2020 strategic planning exercise (IOC 2014). Munich’s anti-bid activism played a significant role: after voters narrowly approved a bid for the 2018 Olympics, they rejected a second bid for the 2022 Games. IOC president Thomas Bach had participated in the 2018 bid in his previous role as chairman of the national Deutscher Olympischer Sportbund, and blamed the subsequent anti-bid referendum on voters ‘being wrongly informed about quite a number of issues’ (quoted in Hula 2013). But regardless of his critique, reforming the bid process became a dominant theme in Bach’s promotion of the 2020 strategic plan.7

Anti-bid activism helped trigger a collapse in institutional confidence with the concept of ‘legacy’. The legacy concept provides a political rationale for linking temporary events to claims about urban development, and by extension a justification for unequal partnerships between host cities and sports federations. It is at the core of the IOC’s two-budget event management model: the model involves an operational budget which is funded with event revenues, and a capital/infrastructure budget which is funded from non-Olympic sources, often public funding. This is intended to prevent the Olympic ‘brand’ from being extended to marginally relevant land investments, and to allow cities flexibility in designing infrastructure that will have legacies after the Games (Lauermann 2014b). But in practice this can result in an infrastructure subsidy for the bid corporation, in which ‘the public pays and the private profits’ (Boykoff 2014b: 3).

The legacy concept has been critiqued extensively by academic analysts from across the political spectrum, especially for the role that it plays in legitimizing expenditures of public funds on private real-estate projects (see reviews in Preuss 2004: ch. 11; Horne and Whannel 2012: ch. 10; Smith 2012: ch. 3; Zimbalist 2015: ch. 4). What is new is a growing uncertainty about it among consultants, planners and other Olympic industry stakeholders (e.g. the Olympic Agenda 2020 reforms). A former director of legacy planning at the London Olympics described the justification of two-budget accounting through references to legacy as allowing ‘a tendency to systematically under-cost the event’ by bid boosters.8 The head of an urban design firm (who has worked on mega-events in over a dozen cities) noted that ‘the word legacy is such a tired, overused word . . . I’m very critical of it and I think it really needs definition . . . “legacy” is just a buzzword for people to justify their salaries.’9 And one consultant – whose firm advises city governments on mega-event planning – summed up this loss of confidence within the Olympic industry, noting that ‘I have never heard a politician or people working in city administration using the term “legacy” . . . it’s a term invented by rights holders [sports federations like the IOC], and that’s one of the reasons why people do not vote for it.’10

The long-term outcome of these trends remains to be seen. However, this does indicate that contesting the bid – rather than the event – provides a way to counteract democratic displacements. Anti-bid activists focus on two strategies. First, they may call for participatory governance over the bid process. As discussed above, launching a direct referendum is a high-profile victory for social movements in part because these referendums are so rare. Second, a more widespread strategy involves broader demands for accountability and transparency in Olympic planning: calling for bidders to provide realistic cost projections and economic impact assessments (or commission independent assessments). For example, Games Monitor (gamesmonitor.org.uk) activists used a freedom of information request to secure and publish host city contract documents in advance of the London 2012 Games. These documents define the specific responsibilities of a host city but are usually embargoed by Olympic organizers. Likewise, using more reliable metrics and more participatory practices can allow normative debate about the opportunity costs of devoting public funds to Olympic infrastructure. For example, No Boston Olympics activists recruited academic experts and government officials into their coalition as a way to deconstruct legacy claims made by the bidders, a messaging strategy which had some success: independent polling found that the more information voters had about the specifics of the bid, the less favourable their opinion of it became (WNEU Polling Institute 2015).

Conclusion

This chapter has explored a form of ‘democratic displacement’ in urban politics. Discussions over the role of mega-events in urban tourism and development – and of anti-Olympic activism in response – focus on the temporary dynamics of these events as they produce short-term economic benefits and anti-democratic ‘states of exception’ in urban politics. The role of Olympics in the broader neoliberalisation of urban policy is a similarly dominant theme in scholarship and in activist circles. Historically, however, anti-Olympic activism has been reactive and localised as social movements protest particular impacts of Olympic planning (Boykoff 2014b). That form of contestation may not engage broader normative debates over whether an Olympics should be hosted in the first place, a point which a subgroup of anti-bid activists have focused upon by calling for votes on the bids before they are approved and for more transparency and accountability in the early-stage planning process.

Some cities may benefit from hosting the Olympics, and the goal of this chapter is not to discourage their hosting but to make recommendations for their planning. Events and other temporary tourist projects are embedded in long-term local development politics, for instance as mega-events draw on interrelated projects associated with other mega-events and failed Olympic bids (Lauermann 2015; Oliver 2014). Thus Olympic urban politics need to be proactive: the stakeholders who promote the bids start their work a decade preceding the event, and Olympic protest is most likely to succeed before the bids are approved, the funding is promised and the contracts are signed. Protest in Olympic cities has been most effective when targeted toward normative debate over the process (e.g. why should the city pursue an Olympics?) rather than issue-specific debate over the project (e.g. how can Olympic impacts be minimized or mitigated?). Critical analysis of boosterish claims about legacy is a particularly effective strategy: demonstrating that the event would likely cost more and produce less than bidders claim is an effective tactic for improving public debate. While social movements are starting to share this expertise, there is still much opportunity for building city-to-city alliances among Olympic protest movements. A clearer picture of the institutional and legal nuances of mega-events planning identifies openings for contestation.