PROLOGUE: Crying for Park Güell

Since Gaudí’s famous salamander was damaged with an iron bar in February 2007, the sword of Damocles has been hanging over Park Güell, threatening its condition as public open space. After several failed attempts, on 25 October 2013 the municipal government’s plan to regulate the access to one of the most visited tourist attractions in Barcelona became operational. Part of the park, designed by Catalan architect Antoni Gaudí and acquired by the city in 1922 after the failure of the original residential project, is no longer publicly accessible. Through the enclosure and control of its central area, Park Güell officially became an open-air museum with restricted access.

From a classical liberal perspective, this decision may look justified. Some of the arguments in support of the closure can hardly be contested: the pressure on a fragile space with high cultural and heritage value; the nuisances produced by mass tourist flows in the neighbourhood; the hassle of informal activities and petty criminality taking place in the park; the high costs of conservation . . . It could be said – as did the hegemonic discourse – that success killed Park Güell, and that the only way to manage this situation was to establish a quota of visitors per hour and regulate their entrance through ticketing and queuing, as has been done in many other World Heritage sites, like the Machu Picchu complex, the Kew Royal Botanical Gardens or the Galapagos natural park. The closure of Park Güell could be considered an example of the ‘tragedy of the commons’ (Hardin 1968), in which the over-exploitation of a common resource dooms it to subsequent enclosure. It could be argued that this decision was thought to create a lesser evil scenario (Hardt and Negri 2009) concerning the management of an urban commons threatened by tourism pressure: a palliative solution to regulate overcrowding through the enclosure of an area tagged as ‘touristic’.

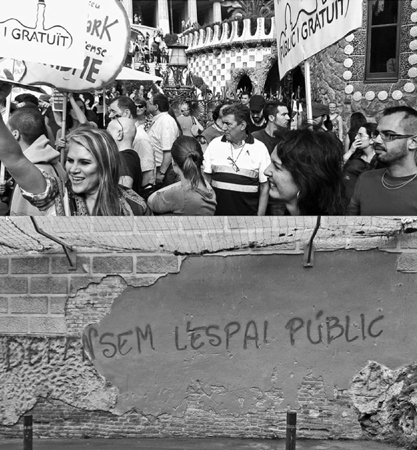

Nonetheless, challenging the hegemonic discourse legitimating the enclosure and regulation, a group of citizens, the Plataforma Defensem el Park Güell (Platform Let’s Defend the Park Güell, hereafter referred to as PDPG) voiced its discontent with this decision. Under no circumstances, they claimed, can tourist overcrowding lead to the privatisation and regulation of a park which would prevent public and free access for everyone. Without denying the unique value of the site and while acknowledging the effects of it being one of the most visited places in the city, the PDPG argued that the park has to remain a public space. And here comes the main paradox of the contestation: by advocating the right to access the park for everyone, with no distinctions, the claim also includes tourists – the very ones whose mass presence justified the regulation. While being fully aware that such mass appropriation is widely seen as the main problem to be solved, the ‘cry and the demand’ for the right to the city (Lefebvre 1968) made by the PDPG transcends the boundaries which frame the tragedy. Thus, proposing an exercise of commoning beyond the place-based community’s interests, the PDPG assumed a relational and compositionist approach (Latour 2010) in order to defend the right to public space. The commoning process is not understood as a claim for historical accumulation rights (Linebaugh 2008), but as the right to participate in and negotiate – and so to produce – urban space with all the inhabitants, without excluding tourists. What we term here the ‘Right to Gaudí’ has become a struggle against the urban strategies of privatising and enclosing public space due to tourist overcrowding. At the same time, the discourse of the PDPG has unwittingly turned into an opportunity to redefine the position of local community groups and urban social movements with regard to tourism issues, shifting the question from ‘how to protect the city from tourism’ into ‘how do we compose the city along with tourism’, and thus eschewing a logic of dualism (tourists vs locals) in the production of tourist places.

Leaving many of the details of the struggle surrounding the enclosure of part of the Park Güell aside for the sake of brevity, this chapter – structured as a Greek tragedy – will focus on the learning process (McFarlane 2011) which has emerged through the enclosing and commoning process. Following this brief Prologue, the Parode presents a short explanation of the park’s tragedy prior to the execution of the regulation plan. The tragedy then continues with three Episodes and three related Stasima illustrating the enclosing-commoning process of the park. Following the analytical approach proposed by Jeffrey et al. (2012), the process has been addressed in its multiple dimensions, through the intertwining of materiality, spatiality and subjectivity. In the final chapter – the Exode, after the unfolding of the tragedy – some concluding remarks are made on the opportunities to learn from the process, i.e. how to claim the ‘right to the tourist city’.

PARODE: Something must be done

The tragedy of the Park Güell must be understood within the context of the decade-long strategy of turning Barcelona into one of the most popular urban tourism destinations in the world. The Olympic Games of 1992 and the subsequent transformation of Barcelona’s cityscape put the city on the global tourist map; since then, the city has hosted millions of tourists, with the visitor count growing from 2.4 million in 1993 to 7.5 million in 2013 on the basis of hotel occupation alone (Barcelona Turisme 2013). When all types of accommodation are considered and day visitors included, tourism flows in Barcelona were estimated at around 27 million visitors in 2013 (Ajuntament de Barcelona 2014), in a small, dense city of 100 square kilometres and 1.6 million inhabitants. Beyond any discussion of the costs and benefits involved, tourism-related activities have become consolidated as one of the leading forces in the economy and in the production of the city. In the context of the acute economic recession of the late 2000s, the tourism sector has continued to be one of the main foci of public and private investment. It is only at the beginning of the 2010s that the increasing pressure provoked by tourism on the everyday life of residents in certain neighbourhoods has triggered critical voices denouncing the development of ‘tourist bubbles’ (Judd and Fainstein 1999). Many of the expressions of popular discontent and demands have been channelled by the traditional neighbourhood associations.1 A wide array of claims have emerged in relation to the citizens’ discontent with issues such as traffic problems related to tourist flows, illegal short-term holiday rentals or the misbehaviour of tourists in public space. The defence of the Park Güell against its enclosure has been one of the mushrooming local mobilizations around the impacts of mass tourism upon the city’s neighbourhoods and residents.

In order to frame our case study, it is also important to highlight a dual process made of two highly interconnected dimensions. Firstly, the increase of visitors to the Park Güell has been initiated by the public sector-driven marketing strategy ‘Gaudí’s Year’ in 2002. Conceived to commemorate the 150th anniversary of Antoni Gaudí and intended to give a new value to the artist and his work in Barcelona through new activities and facilities, this promotional branding exercise turned all of Gaudí’s heritage sites into major urban attractions: the Gaudí effect. Before 2002 the Park Güell was not unknown. But the steady promotion of the park, marketed through the visual icon of the Salamander – a powerful metonymic object reproduced everywhere – together with the improvement of accessibility to the park (located on the top of a steep hill) through sightseeing buses, private coaches’ parking lots and outdoor escalators – turned the park into one of the most visited free attractions in the city.

Secondly, in parallel, as the park was getting more crowded, local activities were disappearing from its spaces. Public events and festivals that once took place in the park were cancelled and programmed elsewhere; community activities such as traditional dance gatherings were banned from the park; children’s activities were circumscribed to specific playground areas; and mundane everyday practices, although persistent, became invisible in the central space of the park at peak visiting hours. Touristic practices thus became dominant through a threefold process encouraged by the local administration: place promotion, restrictions of local uses and practices, and a decline in the critical mass of local users’ activities.

Unfortunately, there has been no regularly published data to give evidence of the growth of visitors’ numbers in the park. In 2006 a newspaper estimated a quantity of 2,000 to 3,000 visitors per day (Brodas 2006). In 2009, the first version of the regulation plan increased this estimate to 14,400 visitors per day. The last published count, accompanying the last version of the regulation plan in 2013, raised the figure to 25,000 visitors per day – although it was calculated during the peak period of the summertime. However, despite the unreliability of such estimated accounts, the overcrowding of the park was both a fact and a concern. Local newspapers frequently denounced an ‘unsustainable situation’ and the ‘need for regulation’, reporting any noteworthy incident in the park. In the mid-2000s, some local residents started to voice concerns about the lack of maintenance, the insecurity of the park and its overcrowding. But the attack on the Salamander in February 2007 by two people armed with an iron bar, which damaged its mouth, was the turning point for the City Council to embark on the preparation of a regulation plan. After a few meetings with a number of local stakeholders, a first version of the Integrated Action Plan was presented by the municipal government in July 2009. Conceived as a broad management plan, it proposed, among other things, to control and limit the access of visitors in order to diminish the impact of ‘uncontrolled tourist visits’ (Ajuntament de Barcelona 2013). Such control of visitors was to be implemented in the area of the park declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1984, that is 17 hectares out of the total surface of the park, including a public school. This space, surrounded by other public and private facilities, is used by local residents not only as a space of leisure but also as a connecting corridor with the surrounding areas.

However, this first plan failed because of the complete lack of support from relevant local stakeholders. No residents’ associations, no collectives, no political parties except those in the government coalition endorsed the Plan. During this first period, from 2009 to 2011, an assembly of existing neighbourhood associations was created under the label Coordinator of Park Güell, and became the most active collective opposing the regulation plan. Its mission statement was clear: avoiding the closure and the privatization of Park Güell. The Coordinator platform collected more than 20,000 signatures; organized rallies; alerted international consulates denouncing the City Council’s plans; and obtained the support of other broader collectives such as the Federation of Neighbourhood Associations of Barcelona (FAVB) and the Public Gardeners’ Union Committee,2 among others. Due to this political failure, the idea of regulating entry to the park was temporarily put aside, although refurbishment works were carried out. But the tragedy was still there, and the local public opinion periodically expressed itself against the ‘degradation’ and the ‘insecurity’ of the park – an unsustainable situation represented by photographs of half-naked bodies sunbathing on shattered benches, illegal sellers displaying cheap plastic souvenirs or visitors taking photographs of their friends riding the back of the Salamander. ‘Something must be done.’ And so was it.

EPISODE I: The lesser evil scenario

After the local elections of May 2011, a new political party (from the centre-right) ruled the City Council until May 2015. Although some members of that party had, in previous years when still in the opposition, assured that they would not close the park, a discussion process was set in motion to prepare a new plan to regulate the impact of visitors on the Park Güell. The new plan’s objectives displayed some crucial differences from the previous one’s. First, the new proposed regulation affected a smaller area, the most attractive (and visited) part involving 8 per cent of the total park area. Ignoring the delineation of the UNESCO designated area, and with the legitimation of the History Museum of Barcelona, the City Council arbitrarily declared the regulated zone as the ‘monumental’ one. Such a regulation was proposed without fencing the zone, but by setting up removable ribbons and checkpoints and contracting a security team to control access. The monumental heritage would be thus preserved and the rest of the park would remain freely accessible so as to allow functional and leisure uses in it. According to the official discourse (Ajuntament de Barcelona 2013: 6), the Regulation Plan aimed ‘to preserve the right of neighbours to enjoy their space’ and ‘to recover the park for the city’. Secondly, the plan fixed a maximum quota of 800 visitors per hour and an entry fee. To avoid paying a fee, neighbouring residents and the school community inside and around the park could apply for a free access card. Moreover, any EU citizen, living or not in Barcelona, could fill in a public register and, after a week, be allowed to book a visit in the ‘monumental area’, limited to 100 such visitors per hour. By limiting the access to a fixed number, the City Council aimed, on the one hand, ‘to conserve and protect a unique heritage’ and ‘to optimize the experience of the visit’ (ibid.). On the other hand, by making tourists pay but allowing neighbouring residents to enter for free, they aimed ‘to improve the quality of life of residents, reverting the benefits generated by tourist activities’ (ibid.). Thus the plan proposed to enclose the ‘monumental zone’ to take the pressure off the rest of the park, while generating funds to sustain the preservation of the park’s heritage. The park was converted officially into an ‘open-air museum’.

This new ‘lesser evil’ scenario changed the framework of the negotiation process with respect to the previous plan. A formal top-down ‘participatory process’ was set up ad hoc by the District government, consisting of five sessions aimed at generating consensus among the various stakeholders. The first meeting was announced publicly, and more than 50 people participated. However, the District Council rapidly announced the need to reduce this number by half, by cutting out representatives of the entities from outside the five neighbourhoods surrounding the park, but retaining many people with no clear representative mandate. From that point onwards, the meetings were no longer publicized. During the five meetings – from September 2011 to October 2013 – nothing was ever negotiated nor decided jointly with the attendees in a public discussion. Some of the relevant stakeholders did not join in the expected ‘consensus’, showing dissent from the beginning of the process; other critical voices emerged during the process. The implementation of the regulation plan, moreover, was formally initiated while the participatory process was still taking place, with the approval of a 2 million euro contract in December 2012 for the infrastructural works necessary to put the regulation system in place: demarcation wires, ticket offices, street pacification measures, etc. This debate did not serve to ‘reveal the truth about the controversy to the audience’, as Walter Lippmann wrote many years ago, but to ‘identify the partisans’ (Lippmann 1993 [1927]: 129). In this respect the Coordinator platform, which had opposed the previous plan, showed its inconsistency when some of the leading actors agreed to the new conditions referred to below. Moreover, the political parties with representation in the District Council did not mobilize against the new plan, and either agreed with the enclosure or avoided any positioning in the face of such controversy. It was in this context that the PDPG emerged to catalyse the voices of contestation against the enclosure plan.

The PDPG was officially constituted in July 2012 to pursue the opposition against the enclosure in a very different way from the previous Coordinator platform. Instead of being driven by the traditional neighbourhood associations, the PDPG was the result of an assemblage process, with its core coming from the neighbourhood assembly of the 15M Indignados movement3 (see Corsín Jiménez and Estalella 2011), joined by former members of the disbanded Coordinator platform, people from other local collectives, members of marginal political parties, artists, craft sellers working in the park and individuals who just wanted to ‘do something’ against the plan. Thus a heterogeneous collective of groups and individual with different trajectories was assembled through ‘temporary, contested and partial practices of articulation’ (Featherstone 2011: 141).

The PDPG was created with a clear orientation towards a single issue with a simple and unchanging objective in its foundational manifesto: ‘to keep Park Güell public and free for everybody’ (PDPG 2012), a claim in tune with the idea of the ‘right to the city’, but remote from the hegemonic opinion in the media and city government’s discourse. Thus the PDPG rejected the idea of enclosing the central part of the park as the lesser evil solution and stood firm on that position. At the same time, it also emerged as a response to the opaque practices of the traditional residents’ associations which were rooted in a local frame of reference, prioritizing their own partial interests over a broader, more general interest. The PDPG thus started a ‘commoning process’ against the imminent enclosure of Park Güell.

STASIMON I: Enclosing and commoning

There has been a resurgence of interest and discussions on the concept of the commons within critical or radical perspectives on neoliberal practices of dispossession, destruction and commodification of common social and spatial resources (Brenner and Theodore 2002; de Angelis 2003, 2007; Hardt and Negri 2004, 2009; Harvey 2003, 2012). These perspectives question the liberal idea of the enclosure as the unavoidable solution to address the tragedy of the commons (Hardin 1968) and broaden the notion of the ‘nested’ governance of common pool resources (CPR) proposed by Ostrom (1990). This renewed approach ‘re-envisions the commons outside of the public-private dichotomy and introduces the social, cultural and political practices that allow new possibilities, thus reconstituting the commons as an object of thought’ (Eizenberg 2012: 766). Thus the commons here are not merely a matter of property regimes but ‘an effect of a social practice of commoning’ (Harvey 2012: 73) constructed through the relational process within and between a group (a community) and an existing or yet-to-be-created heterogeneous (common) resource.

From a spatial perspective, commons have been tackled in closed connection with three main interrelated ideas. First, the idea of ‘accumulation by dispossession’ (Harvey 2003) explains neoliberal enclosure practices in urban space in relation to the need for capitalism to solve the permanent cycles of over-accumulation through an analogy with Marxian ‘primitive accumulation’. Second, the idea of commons as a practice of interaction, cohabitation and cooperation is related with a biopolitical mechanism – that is, one in which what is directly at stake is the production and reproduction of life itself, and which refuses ‘to let the bodies be eclipsed, and insists instead on their power’ (Hardt and Negri 2009: 38). Finally, the Lefebvrian idea of oeuvre and the principle of ‘the right to the city’ have been crucial to translate both the concept of the commons – the whole city as a resource permanently under construction – and the commoning process as a political horizon, to the urban sphere without losing sight of spatial production (Lefebvre 1968).

Many recent works engage with what has been termed urban commons (Blomley 2008; Chatterton 2011; Hodkinson 2012) through the analysis of processes of enclosing and commoning public spaces (Foster 2011), community gardens (Eizenberg 2012) or infrastructure (Corsin Jiménez 2014). Nevertheless, such critical perspectives have barely been introduced in tourism studies, which mostly address the question of the commons in a liberal or institutional frame of analysis. The main articles on this subject have been focused on exploring the economic values of communal property land (Bostedt and Mattsson 1995), on analysing how the property regime determines the structure and evolution of tourist destinations (Russo and Segre 2009), on evidencing the challenges of managing natural resources threatened by overuse and a lack of investment incentive (Healy 1994, 2006), or on enhancing the value of the tangible and intangible resources to assure their sustainability as tourist products (Briassoulis 2002). Although not explicitly mentioning the issue of the commons, some authors have evidenced the effects of the priority given to tourist activities on urban communities, mainly focusing on marketing strategies and tourism-related urban redevelopment processes (Colomb 2011; Fox Gotham 2005; Fainstein and Powers 2006; Novy and Huning 2009), or calculating the impacts of tourism on a community and its quality of life (Hoffman et al. 2003; Pearce et al. 1996; Uysal et al. 2012).

The following episodes aim to explain the enclosing-commoning process of the Park Güell in order to understand the tragedy as a ‘generative spacing’ by identifying ‘how it produces specific materialities, spatialities and subjectivities’ (Jeffrey et al. 2012: 3). Such an approach allows us to move beyond grand narratives of dispossession triggered by neoliberalism – the prevailing discourse from a political economy perspective – and to explain the phenomena in a more situated, heterogeneous, complex and embodied way. By doing so, it makes it easier to identify singularities about, and gather the knowledge emerging from, each specific enclosing-commoning process (Hardt and Negri 2009).

EPISODE II: Mobility and maintenance come first

In between the failure of the first plan in October 2010 and the local elections in May 2011, many enhancement works were carried out in the park for a total of approximately 10 million euros, including the design of internal pathways, the erection of railings alongside the inner viaducts, the improvement of drainage pipes, wood maintenance, the improvement of surrounding streets, the redesign of the coach parking lot, the replacement of the fences surrounding the whole perimeter of the park, and the construction of new escalators to access the park. In spite of such huge investments, a number of neighbouring residents continued to denounce a lack of maintenance, problems of mobility and insecurity in the park.4 Even the Coordinator platform, whose main focus was against the enclosure of the park and its privatization, spoke out against the ‘degradation’ of the park and denounced the lack of policing and the declining number of public garden workers. Many things were done, but they were not enough: tourists were still overcrowding the place, jumping over the Salamander and having picnics on the famous Jujol benches. Informal sellers were still displaying their blankets full of one-euro souvenirs. Traffic jams were still affecting the neighbourhood every weekend.

In September 2011, the District Council started the above-mentioned participatory process. New players entered the game with new intentions and a shift in politics, practices and discourses took place. The central issue remained the fact that the park heritage was at risk due to overcrowding, an issue against which public opinion and the media made constant claims. Nonetheless, the city government’s priorities were now the priorities of others: ‘mobility and maintenance first, then the enclosure’ (Balanzà 2011: 6). Plainly put, heritage could wait – until the problems identified by the neighbouring residents were solved. Apart from giving local residents and the local school community a free pass, increasing police presence in the park and expanding the garden maintenance team, there were still things to be done by the public authorities in order to gain legitimacy and reach consensus with previously critical stakeholders. Hence, in parallel to the participatory process, the District Council organized a number of separate closed meetings with different actors in order to discuss their requests on a face-to-face basis. Such tactics allowed the Council to propose a number of bilateral agreements on problems beyond the enclosure, mainly related to mobility and maintenance. Some issues, like the nuisances generated by sightseeing bus stands, remained unresolved, but for others – like the position of the taxi rank or the regulation of the coach parking lot – new solutions were found. When there were no technical problems to be solved, the Council awarded public recognition to the leaders of the residents’ associations or granted them the organization of events such as the festival to commemorate the centenary of the park. Myriad small tactics, difficult to trace yet very effective, served to dismantle and fragment the main critical issue – heritage protection and the enclosure plan – into small manageable ‘pieces’, allowing the government to build up consensus for the new enclosure plan.

After witnessing how the Coordinator platform had lost force in the confrontation against the plan, the PDPG was constituted as a very issue-oriented collective with the aim of maintaining Park Güell as a public and free space for everybody (Figure 13.1). The closed and opaque nature of the above-mentioned ‘participatory process’ led the PDGD to publicly denounce such divisive meetings and co-opted agreements between parties. Their position against any enclosure was very firm, supported by complex and diverse arguments summarized by the following four principles (PDPG 2012). First, the enclosure will definitely wipe the community uses out of the park, transforming it into a ‘tourist container’. Second, the problems of the park do not originate within the park, thus the enclosure will not solve anything. Third, the alternatives to avoid the enclosure are more complex, but also much more just and sustainable for everybody. Fourth, the enclosure will create a precedent for future action in other overcrowded spaces in the city.

The PDPG was standing, on the one hand, for a highly ideological – not necessarily symbolic – ‘cry and demand’ for the ‘right to the park’, which had to remain public and free. On the other hand, it was responding to the complexity of the situation with a very hybrid and practical approach: claiming a shared responsibility, asking for heterogeneous solutions, advising against the risks which the enclosure would have beyond the park, even beyond the neighbourhoods surrounding the park, i.e. trying to argue that the closure and subsequent segregation of uses would not only leave the problems of the park unsolved but would produce other problems elsewhere. Such a practical translation of the ‘right to the city’ was neither welcomed by policy-makers nor by the local stakeholders or the media.

The complex position held by the PDPG was clearly going beyond the scope of their actions and involved many issues which the regulation plan could not control. The PDPG aimed too high: managing the park fairly implied revisiting, among other thing, the overall tourism promotion policies of the City Council – a challenge in a city where tourism has, in recent years of economic recession, been the goose that lays the golden egg. Local stakeholders felt that their face-to-face bilateral agreements with the District and their political capital were under threat when confronted with an approach that combined broad claims about the right to the city with incremental enhancements of the place. The media did not value the practical proposals of the PDPG and recurrently criticized what they perceived as the ideological nature of the ‘right to the city’ position, keeping the focus mainly on the visual impacts of overcrowding and quantifiable issues such as the number of visitors, investments and costs. Divisive tactics were winning the battle. Complex approaches did not convince anybody. Alliances were not strong enough to bear influence. The only opportunity left to the PDPG was the mobilization of public opinion, but this was not an easy task.

STASIMON II: Thinking the park beyond the park

The PDPG was dealing with the common as ‘a kind of gathering of multiplicities through the political work of assembly’ (McFarlane 2011: 212). Two crucial questions emerge from the previous episode. The first has to do with how to deal with a ‘politics of place beyond the place’ (Massey 2007: 188) and, consequently, how to face responsibilities in an utterly place-based political scenario. This has to do with the assumption of a relational ontology of space. According to Massey (2005), space is the product of interrelations, the sphere of the possibility of multiplicity and heterogeneity, and it is always under construction. In this perspective, there is no Park Güell in essence. The park is much more than a ‘Catalan Arcade’5 or an ‘open-air museum’: it is also a recreational site replete with mundane, everyday practices. Thus the park can be conceptualized in relational terms as configured by translocal and mobile trajectories, interactions and technologies that perform and produce the space. Tourists, elderly residents, children, dogs, sellers, policemen, maintenance vehicles, images, postcards, souvenirs, cameras, policies, plants – all of them configure the space with different rhythmical patterns over time. This approach to the park allows us to unearth the translocal character of the heterogeneous agencies producing the place through space and time. Moreover, a relational approach allows us to think of a ‘politics of place responsibility’ (Darling 2009) in a dual way: on the one hand, as an account of the tensions of negotiating the multiplicity of elements that construct contemporary spaces; on the other, as a demand to take responsibility for the global flows and connections that help to constitute such a spatial multiplicity. This relational approach helps to challenge what Purcell (2006) has called the local trap, that is the assumption that the local scale – the five neighbourhoods surrounding the park in this instance – is always the most democratic option to frame the decision-making process. In this case, it was showed that the neighbourhood scale allowed certain tactics of control to develop.

The second question, closely intertwined with the first, can be formulated as how to play up the issue in order to ensure the political involvement of the public in the controversy (Marres 2007), understanding the public as ‘all of those who are affected by the indirect consequences of transactions to such an extent that it is deemed necessary to have those consequences systematically cared for’ (Dewey 2012: 16). The fragmentation of the issue into a series of individual solvable problems confronted the PDPG with the need to engage as many voices as possible in the debate, in order to shift the discussion back to the broader, city-wide effects of the enclosing. However, this double movement of publicizing the issue and decentring the urban object – the park – to outline distributed responsibilities was one of the crucial limits the PDPG faced during the commoning process. Apart from the difficulty of negotiating the space through everyday or community practices and the incapability of dealing with the divisive tactics of technical and participatory arrangements charged with ‘moral and political capacities’ (Marres and Lezaun 2011: 495), the attempted mobilization of the public found another limit: the difficulty to enrol subjects who have been detached from the commons even before the enclosure.

ESPISODE III: Making tourist things public

The PDPG was created with the agenda to widen both representation and participation in the debate beyond the geographic limits of the surroundings of the park. This can be explained, on the one hand, because of the previous experience with the Coordinator platform, which shifted position when direct benefits were offered to the participating actors, as outlined earlier in the chapter. On the other hand, there was an attempt to convert the ‘Real Democracy Now!’ slogan which drove the mobilizations of the Indignados movement of May 2011 into an issue-oriented claim for the park as an urban commons. Nevertheless, the alliances forged with many local and regional institutions (such as the FAVB) and minor political parties – such as the CUP (Candidatura d’Unitat Popular, a radical left-wing Catalan independentist party) – were not sufficient to allow the PDPG to influence the decision-making process. This situation forced the PDPG to start seeking support beyond the local scale and to try to enlist new solidarities by calling to the wider public. In March 2013, an online petition against the enclosure was set up, and more than 50,000 signatures were collected in two weeks. Rallies, festivals and a documentary were prepared in a very short period of time to raise awareness about the effects of the imminent enclosing.

However, in order to keep the public away from the controversy – once the support of place-based stakeholders had been assured by solving ‘their’ localized problems – the City Council set up a three-pronged strategy aiming at alienating the park from the community and the public. Firstly, all programmed festivals and events planned in the park were cancelled some years prior to the controversy over the enclosing.6 The park, once the centre of many cultural and community activities, was erased from the city’s public cultural map. Secondly, there was a clear discursive strategy to label the area to be regulated under the ‘touristic’ category. In an arbitrary way, there was suddenly a touristic area and a touristic schedule referred to in many official publications: not a public park, but a touristic park. Such a label was accompanied with a new, highly questionable visitors count estimate, carried out over four days in July 2012, which increased the total reported amount from 4.5 to 9 million annual visitors. This allowed, thirdly, public authorities to give visitors the responsibility to take care of the park by paying a fee, which owed public legitimacy to the city government through the statement ‘Tourists will pay, residents won’t’. But only the people with a registered domicile in the surrounding neighbourhoods and the school community had the privilege to freely access the park whenever they wanted. In order to avoid paying the entrance fee, the remaining 85 per cent of Barcelona residents, as well as European citizens, would have to sign a register in person and later would be able to book a pass and visiting time to enter the enclosed ‘monumental’ area. The efforts of the PDPG to dismantle such a system came too late, and the impact of its claim that ‘everybody but a minority is treated as a tourist’ was very weak. The argument of the city’s ombudswoman, whom the PDPG asked to evaluate the legality and legitimacy of the enclosure, was crucial. Despite her criticism of the visitor numbers accounting method, the lack of public communication about crucial information and the lack of democratic guarantees during the debate, and while in favour of re-scaling and widening the issue, her sentence ended with an acceptance of the closure as a ‘reasonable solution’ (Síndica de Greuges de Barcelona 2013: 15).

STASIMON III: New subjects, old forums

After showing the impossibility for the opposition to the enclosure to escape from the orchestrated local trap, and how the issue was purposely blurred and dismantled by public authorities, it is worth reflecting about two processes which ensured the success of the enclosure. First, there was a subjectification of the enclosure process (Jeffrey et al. 2012) towards what Ong (2007) called a ‘market criteria citizenship’ setting a ‘new mode of political optimization’ in which the state – the City Council in this case – injects into citizens the idea of co-responsibility for the municipal budget. In a moment of sharp economic crisis, the evocation of the opportunity to make others, the ‘tourists’, pay for the maintenance was very effective in order to disenfranchise the public from the issue and ‘normalize’ it. The formation and the further action of PDPG was a response to such an enclosure process through subjectification: it sought to shift representation patterns and advocate a translocal scenario of alliances (Featherstone 2009) between the constellation of agents implicated in the production of the space in order to address the enclosure. Nonetheless, there were serious difficulties in making such alliances effective. None of the achieved enlistments of new agents were powerful enough to shift things. There was no support from larger political parties and other more widely representative institutions to mobilize a broader public opinion against the enclosure. Moreover, tourists had no institutional representation to defend their options, but on the contrary were treated as clients and pushed out of the political debate as the main guilty actors in the tragedy. Many of the residents agreed with this situation which was supported by the discourses and actions of the public administration.

The second process has to do with the lack of political spaces in which to deal with the complexity of urban tourism-related issues. Using Latour’s (1993) terms, the park suffered a double process of purification in the public sphere by being turned into a tragic touristic place refuting all other multiple realities and, at the same time, by seeing its hybrid composition used in a very tactical way in order to dismantle both ideological and practical critiques. The techno-political mechanisms of control discussed before were very difficult to challenge through communicative action alone within the terms of the political debate set by the local government. The greater the acknowledgement of the hybrid, mobile and translocal composition of the commons, and the more public was the distribution of responsibilities, the fewer chances the PDPG had to negotiate, confront or reverse the effects of such a messy reality in hybrid forums (Callon et al. 2009). Discursive action alone was not enough to confront entrenched positions and claims to deal with all the things at stake in the commons. All opportunities to acknowledge complexity and seek for a better balance between ideology and technology in the public debates were denied. Taxi ranks, sightseeing bus stops, escalators, security, heritage interventions or tourist promotion – among other issues – remained outside the participatory process and discussions about figures, budgets and ratios were confined to technical matters.

EXODE: The right to negotiate the tourist city

The park was finally enclosed on 25 October 2013. The PDPG lost their battle. There was no deus ex machina nor any miracle. The pathos was consumed with the enclosure and the erasure of practical opportunities to negotiate a space that turned from public space to a monumental tourist area. However, as in many Greek tragedies, the death of the main character could be used as a pharmakon, a piece of moral advice, for the learning benefit of other protagonists in other places. In this sense, the ‘cry for the right to the Park Güell’ has helped us unearth new knowledge bases that could guide the empowerment of social and political actors in the search for the commoning of the tourist city.

It should encourage us to eschew the local trap by recognizing and assuming that ‘inhabitants [not just enfranchised citizens] have the right to participate centrally in the decisions that produce urban space’ (Purcell 2002: 104), including tourists. Dealing with tourism irrevocably forces us to assume an outward-looking perspective on our cities (Massey 2007), which are simultaneously the result of, and the sphere of possibility for, translocal mobilities. Tourists could not be singled out as the guilty party in this story without the risk of legitimizing the enclosure of this public space. The delimitation of tourist spaces may induce the segregation of the space precisely because of its touristic character. Labelling places as touristic and enacting them as such may erase the chance to negotiate the space through the mundane practices and performances beyond tourism. Multiplicity, here, is treated as a political achievement – beyond an ontological assumption: the one that maintains the chances for the enactment of different multiplicities in and through the space. On the contrary, if one limits and encloses tourist places, the result is often regulated and controlled spots where nothing but tourism can happen.

If another common world has to be built, we have to think about places beyond the representational approach – transcending the notion of what is ‘touristic’ or ‘authentic’ and what is not – and focus on how decentred, related and neglected the constituting parts of any urban controversy are. The right to the city cannot be an essentialist stance, but the effect of a heterogeneous assemblage process that has to be ‘constantly shifting and sifting [of] spatial imaginaries of networks, hierarchies, and scales’ (McFarlane 2009: 564). The challenge is how the inhabitants of a city can think of the right to the tourist city with and through the agency of tourism, not relegating tourists to enclosed spaces, since by doing so, they would be enclosing themselves too.