Singapore’s ‘unique selling point’ is to be a . . . first world system in a complicated and non-first-world part of the world. We have new Casinos and a ‘river safari’, like the Amazon!

(Singapore Prime Minister Lee Hsien-Loong ‘On the Record’ at Chatham House, London, March 2014, as observed by author)

In summer 2015, two significant events occurred. Firstly, Singapore celebrated its 50th birthday, a year-long event marked by celebrations, speeches and much international publicity. Secondly, in July, UNESCO announced that the Botanic Gardens would officially become Singapore’s first World Heritage Site – only the third botanical garden in the world to obtain that designation (after Kew Gardens, London, UK and Padua Gardens, Italy). The Botanic Gardens are one of Singapore’s premier tourist attractions, featuring a ‘national orchid garden’ containing rare, vibrant orchids named for various visiting celebrities and dignitaries, such as Queen Elizabeth II. Originally established by the colonizing British powers during Victorian times, the gardens feature native and non-native tropical flora, meandering pathways through palm groves, ponds, and a scattering of restaurants, cafes and event venues such as a symphony bandstand.

About one mile away from the Botanic Gardens is Bukit Brown Cemetery, also dating back to the British colonial era but designated as a pan-Chinese cemetery – the largest outside of China, and the resting place for many of the nation’s most prominent families (including the family of founding father Lee Kuan Yew). As the Botanic Gardens join the prestigious UNESCO family, the cemetery is slated for destruction and redevelopment into a new housing estate and underground station as part of one of Singapore’s designated ‘new towns’. The new town is planned by the Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA) and Land Transport Authority (LTA) to help Singapore absorb its expected population growth of up to 7 million by 2030 (Singapore Government 2013) and to ease transport congestion. Construction has begun on a portion of the site; by 2030 the entire cemetery is planned to be redeveloped.

‘Save Bukit Brown’ – the effort to preserve Bukit Brown Cemetery – has emerged as one activist movement with particular traction, as a disparate and loose network of residents, tourists and various affinity groups who contest the destruction of the site and, more broadly, the appropriation of the built environment for consumption-led urban development, in which tourism plays a major role. The living face off against the dead (and their allies) in one of the most hotly contested battles currently underway amid the reinvigorated activist milieu in a Singapore that is rapidly changing. The battle for Bukit Brown represents the type of alternative pathways (and narratives) that are being claimed by part of the local population, backed by (some) visitors, and the ways that such alternative narratives are performed in the built environment.

This chapter contrasts State-promoted tourist sites such as the Botanic Gardens with the grassroots-led battle to preserve Bukit Brown Cemetery, using empirical examples from field research conducted in Singapore1 to paint a picture of grassroots activism in the authoritarian tourist city. I will suggest that the dominant narrative for tourism in Singapore is increasingly being challenged by a grassroots network of transgressive ‘guerrilla tourists’: I argue that this loose network, containing activists, artists and those ‘just taking part’, is rewriting Singapore’s tourist script by going ‘off the pathway’ (De Certeau 1984) and forming a new tourist geography. This set of practices, which I term ‘guerrilla tourism’, takes place on foot (through the act of walking), but also occurs in/through narrative practices via social media, blogs, word of mouth and sites such as Tripadvisor. The resulting reshaping and reappropriation of the top-down, normative tourist script in Singapore represents a growing challenge to the entrenched power structure, its elite spaces and associated elitist policies that have defined Singapore’s nation-building (but is increasingly disconnected from many Singaporeans). By envisioning Singapore’s tourist landscape as catering to a particular international aesthetic (colonial-chic and monumental in scale) at the expense of more indigenous, unique characteristics, the state has alienated (and galvanized) the grassroots and traditional Singaporean ‘heartland’ (see Tan 2008).

Through ‘guerrilla tourism’, the public commons – heritage and the natural/built environment – are being re-emphasized. The tourist city is being questioned and contested, rewritten and rescripted from the ground up, through practices which shake (and challenge) the authoritarian state’s ability to plan, make and preserve urban space in the name of tourism development. Firstly, I will give a brief overview of how Singapore has seen a tourism turn in recent years, with major investments in globalized tourism landscapes. Next, I will briefly show how the prioritization of elite tourism spaces is emblematic of growing divides and schisms within Singapore, and how contestation and activism has been rising. I will then introduce the concept of ‘guerrilla tourism’ and use the case study of ‘Save Bukit Brown’ to demonstrate how grassroots efforts are seeking to reclaim and reappropriate the built and natural environment and increasingly question the dominant tourist narrative, before concluding with what the case of Singapore reveals about ‘guerrilla tourism’s ability to rewrite the urban pathway.

From ‘staid’ to ‘sexy’: the reimaging of Singapore through tourism and consumption-led urban development

Singapore has made a sweeping entrance into the first tier of world cities. From its colonial origins to today’s sweeping, glitzy cityscape, the City-State has undergone a remarkable physical (and economic) transformation that is fairly unique in the world. In the words of the founding Prime Minister, Singapore has transitioned from ‘Third World to First’ in a single generation (Lee Kuan Yew 2000). Tourism has been central to this repositioning and reinvention and has represented a key economic strategy over recent decades (see Chang 2001, 2004, 2016; Chang and Huang 2009, 2014; Chang and Lim 2004; Chang et al. 2004). The City-State’s tourism turn has seen the construction (and promotion) of a variety of attractions aimed at reimaging and reinventing Singapore from a (perceived) staid, conservative, tidy business centre and air-stopover to an ‘all-in-one destination’, capable of attracting tourists to stay (longer) and spend (more). As local author Neil Humphreys wrote (2012), the island got ‘sexy’, a stark departure from its squeaky-clean reputation.

Much of the new tourist infrastructure is spectacular in scale: the Moshe Safdie-designed Marina Bay Sands casino, hotel, shopping and entertainment complex, towering over Singapore harbour and featuring the world’s largest (rooftop) infinity pool; the new Universal Studios Singapore at Sentosa Island; the Gardens by the Bay (including the enclosed and air-conditioned Flower Dome and Cloud Forest) and the River Safari and Night Safari – are just some of the many efforts carried out by state planning authorities in consortium with developers (some which are state-owned, such as Temasek Holdings) and multinational corporations (such as Universal Studios). With these ‘experiential’ attractions have come ‘experiential’ amenities (Chang 2016), like luxury shopping malls (such as the Ion Centre on Orchard Road), Michelin-starred restaurants, and upmarket hotels and spas (from the Mandarin Oriental on the harbour to chic boutique hotels ringing the City Centre). Flagship sports and cultural events such as the Singapore Formula 1 Night Race and the Art Biennale have also helped to elevate Singapore’s international reputation as a destination among the global cultural and economic elite.

Singapore’s years of investment in tourism infrastructure, branding and promotion have had tangible results. The Singapore Tourism Board (STB) has charted Singapore’s meteoric rise as a visitor destination: tourism now accounts for some 160,000 jobs in Singapore and (at least) 4 per cent of the City-State’s gross domestic product (STB 2013). Singapore’s tourism promotion efforts have helped grow the number of visitors through the period which included the 2003 SARS2 epidemic (in which visitor numbers to Asia tumbled) and the 2008–11 global financial crisis: international arrivals to Singapore grew from 7.6 million per year in 2002 to 14.4 million per year in 2012, while tourism receipts increased from SD$8.8 million in 2002 to SD$23 million in 2012 (STB 2013: 3). Policy efforts have sought to grow the numbers further, with plans to reach 17 million international visitors by 2015 (SMTI 2011). Meanwhile, Singapore has gained on Macau as a major global gambling destination: in 2011, Singapore tied with Las Vegas (USA) as the world’s second biggest gambling market by revenue (O’Keeffe 2014). This represented a stunning shift in a conservative City-State where gambling was banned until 2005, when Prime Minister Lee announced plans to develop two casinos during a Parliamentary session on 18 April (Arnold 2005).

Global press and media – from the New York Times to airline in-flight magazines – have frequently featured Singapore as a ‘new’ travel destination in recent years (e.g. Cohane 2011); the TV celebrity chef Anthony Bourdain has twice featured Singapore as one of his top food destinations on both of his TV shows (‘No Reservations’ and ‘The Layover’). Language from all of these promotional efforts and feature stories focuses on the new, relaxed, fun Singapore – as contrasted with the old, straitlaced, sterile Singapore: ‘Judging from the number of cranes that dot the skyline, Singapore is booming . . . and, best of all, sexy lounges and rooftop bars are helping the City-State shake off its staid image’ (Cohane 2011).

The makeover of Singapore’s urban landscape into a touristscape ready for global visitors (see Olds and Yeung 2004) has given rise to critical voices in the academic literature. Chang and Huang (2009), for example, explored the cultural makeover of Singapore’s city centre into an homogenised, global geography of ‘everywhere and nowhere’ in which large-scale, commercialised art groups and art spaces were prioritized over smaller-scale, indigenous groups and spaces. The theatres by the Bay and the Esplanade, two new monumental performing arts venues, are highlighted as examples: smaller theatre companies and local artists have not featured as heavily in Singapore’s new architecture of culture.

Such is the extent of the appropriation of, and state imagination of, the Singaporean touristscape. State planning authorities (the Urban Redevelopment Agency, URA; the Economic Development Board, EDB; and the Singapore Tourism Board, STB) along with state-development corporations (Jurong Town Corporation for example) have demarcated ‘new’ tourist spaces (the shopping malls of Orchard Road, the roller coasters and casinos of Sentosa Island) and ‘old’ tourist spaces (colonial-shop houses,3 the posh verandas of the Raffles Hotel). Meanwhile, many spaces and places representative of Singapore’s long, regional, vernacular past are not put forward (in the official script) as places worth visiting and often fall prey to bulldozers. These include spaces associated with the island’s more traditional, less glitzy heritage, from older state housing estates4 to religious sites.

A walk around Singapore’s waterfront, with its massive financial buildings and palm-lined boulevards, brings to mind a host of cities around the world, from Miami to Dubai. The ‘new’ Singapore corresponds to Singapore’s ascendancy into one of the world’s most expensive places (Economist Intelligence Unit 2015) – a designation that has raised critical questions about the impacts of the decision to reorient Singapore to attract global wealth (visitors as well as expatriates). The increasing cost of living, as well as the appropriation of urban space for global tourism and high-end consumption, have corresponded with an increasing socio-cultural divide between ‘cosmopolitan’ and ‘heartland’ (Tan 2008). This divide has generated, in some cases, unease and mistrust between older, more traditional, working-class Chinese, Malay and Indian populations and cosmopolitan groups found circulating in the new ‘sexy’ touristscape (including wealthy mainland Chinese visitors). These schisms – between larger-scale, spectacular, globalized tourism landscapes and smaller-scale, more indigenous places, between wealthy visitors and poorer residents, and between Singapore’s elite and lower-middle classes – cut across the tourist City-State and its micro-geographies.

In the context of this increased prominence attributed to tourism and consumption-led urban development, ‘culture’ plays three roles: a tool to appease, attract and retain the economically important ‘cosmopolitans’ (i.e. the so-called ‘creative class’ – see Florida 2002, 2004); a unifying, nationalistic ingredient that ties Singapore’s multi-ethnic and polyglot population together (such as the annual ‘National Day Song’); but also a potentially divisive wedge, destabilizing national unity in order to justify continued ‘illiberal’ authoritarian control by prioritizing some national visions and identities over others (see Yue 2007). In that context, tourism is developed as a tool to attract ‘cosmopolitan’ elements (e.g. wealthy visitors from around the world) while simultaneously serving nation-building purposes, all the while relying on low-paid migrant labour and pricing out many lower-income Singaporeans – thereby both destabilizing and stabilizing society. Like a Pandora’s box, Singapore’s ‘tourism turn’ has instigated new debates – and contestations – in the public sphere about the use and appropriation of the urban environment.

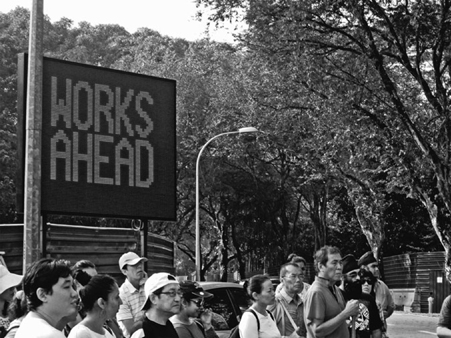

The years paralleling the ‘tourism turn’ have seen growing unrest and louder critical voices in Singapore. Political activism has grown as the City-State has increasingly embraced, and also felt, global capital, global ideas and global visitors (Tan 2008; Goh 2014). Singapore’s status as an outwardly focused, global city is also a leading cause of societal discontent: ripples of the 2008 economic crisis, Occupy and the Arab Spring movements helped to give the opposition political party – the Workers’ Party – its strongest electoral showing in decades in the 2011 general election. In 2012, the first labour strike in a generation occurred and, in December 2013, the first ethnic-related riot since the 1960s took place (in the ‘Little India’ district). It is no accident that the riot occurred in one of Singapore’s designated tourist-spaces: such spaces are increasingly the sites where a variety of tensions play out on the street. In ‘Little India’, urban space is shared by tourists, by a long-standing ethnic community and by migrant workers from the Indian subcontinent. The riots demonstrated how this coexistence is not always peaceful and how tourist spaces can be a battleground.

Inclusions and exclusions in Singapore’s official tourism narrative and promotion

The contrast between the ‘official’ version of Singapore’s tourist narrative versus alternative versions is a theme that emerges in recent literature: sociologist Daniel Goh (2014) used the example of a performance artist’s subversion of an official walking tour of Singapore by ‘walking backwards’ (during the 2009 Art Biennale), while barefoot and holding her shoe in her mouth. Goh illustrates the subtle and complex ways that artists do their part to illuminate new possibilities and challenge the state’s vision (for what tourists should or should not see or do). By walking backwards, the artist was going off-script, off-map and changing the tourist script, demonstrating what De Certeau (1984: 93) describes as a walker in a city stepping ‘off the formal roadway, fashioning their own, uniquely personal pathways’. As such, the transgressive or ‘guerrilla tourist’ steps off the formal tourist roadway, fashioning something more personal and unique.

The contradictory images of an elite, global art fair (the Biennale) and a performance artist ‘walking backwards’ neatly encapsulates Singapore’s tourism dichotomy, and sets the stage for an examination of two places in particular: the Botanic Gardens, Singapore’s first UNESCO World Heritage Site, and the neighbouring Bukit Brown Cemetery, which faces demolition and redevelopment. In the gardens, the City-State’s elites go for evening jogs past trees planted by British gardeners during the reign of Queen Victoria. In the cemetery, ‘guerrilla tourists’, activists, descendants of the buried and those Singaporeans seeking a connection to history and indigeneity walk among the overgrown graves of the nation’s founders in the shadow of encroaching construction machines.

The Botanic Gardens are located amid Singapore’s wealthiest districts, close to upscale shopping on Orchard Road and relics from colonial rule such as the Tanglin Club. These districts feature the private homes of many members of the Singaporean elite but also wealthy expatriates including significant American and British communities. The link between elite visions of Singapore and the promotion of the Botanic Gardens to UNESCO is not lost on some of the island’s critical intellectuals, such as a local intellectual and writer, interviewed in December 2012: ‘The only place that they [the government] will conserve – which is prime property – because it has value: Botanic Gardens. Botanic Gardens . . . And – I suspect because [Lee Kuan Yew] and family jog there frequently!’

The gardens were part of the British Colonial project from the very beginning, with Colony founder Joseph Stamford Raffles proposing a ‘national garden’ as early as 1822. In 1859 the gardens were laid out by botanists in the ‘English Landscape Movement Style’. It is only since Singapore’s independence in 1965, ostensibly, that the Gardens have been truly Singaporean. Still, little of the flora in the gardens is native to Singapore or even the Malay Archipelago: perhaps the most iconic tree, the ‘rain tree’, is native to South America. Colonial evidence is everywhere, from the ‘black and white bungalows’ scattered around the grounds to the orchid garden featuring, among its newest additions, a special orchid named for Kate, the Duchess of Cambridge. The Botanic Gardens are beautiful: their appeal resonates not only with locals who use the space but also with the international press: Wu (2015) listed the Botanic Gardens as the very first thing to do and see upon arrival in the City-State, noting (incorrectly) that the Gardens are Singapore’s ‘last remaining green lung’.

The promotion of the gardens to UNESCO for World Heritage Status fits within Singapore’s broader state policy agenda: the gardens are part of the Prime Minister’s vision for Singapore to be a ‘City in a Garden’, along with other similar spaces such as the Gardens by the Bay and the River Safari. All these spaces share the characteristics of being green spaces. They are also, however, largely devoid of the regional, Chinese-Malay character (culturally, botanically, aesthetically) and an authentic sense of history. These ‘gardens’ are also just that: tended, manicured and curated. Bukit Brown Cemetery henceforth emerges as an alternative green space: a ‘guerrilla’ place to transgress, stepping over branches and under fences. As such, Bukit Brown invites the tourist to ‘step off these formal roadways, fashioning their own, uniquely personal pathways’ (De Certeau 1984: 93).

Conceptualizing ‘guerrilla tourism’ as a form of transgressive tourism: off the formal pathway

Walking is a process of appropriation of the topographical system on the part of the pedestrian . . . a spatial acting-out of the place . . . [and] implies relations among differentiated positions.

(De Certeau 1984: 97)

Cool, old, abandoned buildings, you say? What’s this about guerrilla tourism? First, a disclaimer: visiting old abandoned buildings – be it an empty insane asylum or the remnants of a hulking steel mill – is a potentially dangerous activity.

(Copeland 2015: n.p.)

In this chapter I define ‘guerrilla tourism’ as a particular form of tourist practices that takes place in an alternative space, i.e. a space which is not seen as a ‘mainstream’ tourist site. In other words, it is a form of tourism that transgresses, that crosses boundaries, that involves going, seeing and doing in places that are tucked away, hidden, swept aside or prohibited. Though the term ‘guerrilla tourism’ has not yet been clearly defined, ‘guerrilla warfare’ is often envisioned as non-traditional or underground warfare – rebels hiding in the jungle, etc. – with connotations of violence. In urban literature, the term ‘guerrilla’ has been extended to refer to non-violent but subversive practices of reclaiming urban spaces through unauthorized activities, e.g. ‘guerrilla gardening’ (see Adams and Hardman 2014; Reynolds 2014).

By extension, a similar conceptualization can be extended to ‘guerrilla tourism’ – a sort of rebel tourism, an underground tourism and a tourism that involves the performance of transgression (and within that, potentially, of micro-resistances). This may mean literally going into the jungle (in a place such as Singapore), but in urban contexts (like Pittsburgh or Detroit), this might mean stepping over a ‘closed’ sign to enter an abandoned building, dodging broken glass or venturing out in the dark, after ‘official’ operating hours. A cursory online search of the phrase ‘guerrilla tourism’ revealed the term to be used in unofficial, grassroots tourism advertising and media, normally referring to tourist activities off the beaten track or beyond the normative tourism script. Abandoned buildings, desolate urban stretches or even those spaces envisioned as ‘haunted’ or surreal frequently emerge as such ‘guerrilla tourist’ sites: one promotional article on Pittsburgh, USA (in BootsnAll, an online tourist e-zine) mentions ‘guerrilla tourism’ of Pittsburgh’s ‘haunted’ abandoned industrial districts, remnants of the city’s once-great steel industry (Copeland 2015). However, the term is used informally – not defined or with a reference to use elsewhere.

In academic literature, particularly tourism studies, ‘guerrilla warfare’ has been predominantly linked with the risks to tourism – with authors probing how ‘terror’ and ‘tourism’ impact one another and the ways in which tourists avoid places they associate with danger or risk (Ryan 1993; Brunt et al. 2000). However, other authors have explored how tourists might be actually drawn to such ‘guerrilla places’, how guerrilla war or a war-torn history can evolve into a tourism-generator and ways that tourism can help rebuild war-torn nations (see Chheang 2008 with regard to post-Khmer Rouge Cambodia). As of yet, though, there does not exist a cohesive literature on ‘guerrilla tourism’ as a transgressive or subversive form of tourism and the various contextualities of place, actors and methods through which such forms of tourism are performed across diverse and atypical contexts.

That said, ‘guerrilla tourism’ can be envisioned as an evolution of, and addition to, the literature on ‘off the beaten track’, ‘alternative’ or ‘third place’ tourism (that is more well-defined and has been a feature of tourism studies since the 1990s). Bhaba (1994) explored the hybridity of ‘place’ and ‘culture’, and the way that tourism can be a conduit for alternative narratives and understandings in the post-colonial world (to which Singapore belongs). Hollinshead (1998), however, notes that tourism research should go further to interrogate the spatial practice and performativity of the everyday tourism experience and urges researchers to probe how tourism can both reinforce and challenge ‘people, places and pasts’. Amoamo and Thompson (2010) answer Hollinshead’s call and build upon Bhaba’s exploration of ‘hybridity’ to explore the ways that hybrid Maori identities and differing interpretations of indigenous history in New Zealand present challenges and alternatives to hegemonic narratives, essentialisms and ‘othering’. No such literature exists about Singapore, however, which is (likewise) characterized by a multitude of different ethnic, religious and cultural histories and identities.

The search for ‘authenticity’ is another theme that can be linked to ‘alternative tourism’: Sharon Zukin (2011) highlighted how the search for ‘urban authenticity’ and authentic spaces increasingly drives decision-making (and processes of urban change like gentrification) in the contemporary city. She contrasts ‘authentic’ urban space (independent stores, small-scale architecture) against homogenized, ‘Disneyfied’, corporate urban space, such as New York’s Times Square. Zukin stresses the importance of social media, blogs and sites like Twitter, Yelp and Tripadvisor in promoting and disseminating the ideas of what constitutes ‘authenticity’ and the relationship between cyberspace and urban space. Along these lines, Maitland and Newman (2014) have explored the capability of urban settings to stimulate ‘off the beaten path’ tourist practices and the transformation of urban tourism more generally. The concept of ‘guerrilla tourism’ fits within this ‘authenticity turn’, since ‘guerrilla tourists’ seek alternative experiences and hybrid understandings and definitions of what constitutes space, place and culture. They are tourists, but they are trying not to be too ‘touristy’ and would rather say ‘I am not a tourist’ (see Week 2012). Cresswell’s (1996) definition of ‘transgression’ – exhibiting ‘geographical deviancy’ simply by showing up in a place and assembling (but not resulting in a legitimate threat to the state and therefore not resulting in large-scale societal/political change) – is another way to conceptualize ‘guerrilla tourism’. Whether ‘transgressive’ ‘guerrilla tourism’ can also contain resistances – deliberate acts of contestation – is one question this chapter seeks to probe in Singapore’s context, through the example of Bukit Brown Cemetery and the ‘Save Bukit Brown’ movement.

Doing ‘guerrilla tourism’ in Singapore: a walk in Bukit Brown Cemetery

Adjacent to the Singapore Botanical Gardens (separated by a highway) lies Bukit Brown Cemetery, also known as ‘Kopi’ (coffee) Hill. This is a 200-hectare site of forested hills containing as many as 100,000 graves (Figure 16.1); thus, Bukit Brown is the largest Chinese (ethnic) cemetery outside of China. For this reason, as well as its links to the history of Singapore and the wider Chinese diaspora, its natural beauty and its environmental diversity, it is a site of significant cultural importance, as well as one of the City-State’s largest remaining green spaces.

Construction has begun on a new highway straight through the site, resulting in the exhumation of many thousands of historic graves. The planned destruction of Bukit Brown has made the site a place of activism and has helped to generate a strange and loose network of artists, activists and ‘guerrilla tourists’. ‘Save Bukit Brown’ has emerged as one of the most cross-cutting, tenacious and visible activist movements in the City-State’s recent history, triggering alliances that had not before had such a staging ground around which to coalesce. There have been other efforts to save historic buildings and historic sites: the old national library building, for example, generated outcry when it was demolished for a new road. Yet no historical preservation movements have been able to generate as much international publicity as ‘Save Bukit Brown’ has. This is partly because of the way that the ‘Save Bukit Brown’ grassroots movement has utilized social media to project its campaign way beyond the site itself.

Bukit Brown is one of Singapore’s rare examples of what Foucault (1984) and Soja (1996) described as an ‘other’ (or ‘third’ space): until recently, left alone – untouched by the City-State’s master planning and spared the redevelopment policies that have reshaped most of Singapore. As the space is now being slowly turned into a construction site to feed Singapore’s need for economic and physical urban development, graves are being exhumed and history is literally disappearing into thin air. Steve Pile considered what cemeteries mean to the modern city (2004: 217), pointing to Walter Benjamin’s (1999 [1935]) ruminations of how the ‘dead cling like chewing gum to the heels of the living’ and thus the ‘dialectic of history is brought to a shocking standstill’. Bukit Brown and what it represents haunts Singapore’s modern cityscape. The ghosts of Singapore’s past also haunt the authoritarian state’s version of how Singapore should be represented and used as a tourist city: artists, naturalists, conservationists, historians and those curious to experience something different meet on mornings and evenings to walk among the ghosts, eschewing the shopping mall, the casino and the theme park. A strange network of people and practices has formed in a strange place.

The large size of the site and its ‘other’ status – a spiritual site, a site of the non-living – allow it to host spontaneous gatherings and activities that do not often occur in Singapore. One anecdotal example of the emancipatory (and spontaneous) potential of Bukit Brown (that I learned about on one of the walking tours I joined) was the occurrence of a raucous moonlit rave, held on the site of the largest and most ornate grave in the cemetery well into the early morning one hot night. This was spread wholly via word of mouth – text messages and Facebook posts. By literally dancing on the grave of one of the nation’s most eminent (and wealthy) pioneers, the moonlight grave-rave was a whimsical and subversive reimagining of space. The moonlight grave-rave was only one of many examples of the way that the cemetery has led to practices which have gathered various individuals and groups that may not otherwise have joined together.

The ‘Save Bukit Brown’ movement began as a collective response to the cemetery’s impending destruction through the joined-up organizing of historic preservationists, environmentalists, Taoist groups and artists, as well as a few academics from the National University. The movement started a Facebook and Twitter page in 2011 and slowly gained followers; tours were organized (usually held once or twice a week); and community forums were held at venues around Singapore (including the Substation theatre). The movement continued to grow, culminating in a petition in 2012/13 that (unsuccessfully) aimed to stop development of the site.

Some members of this loose network of Bukit Brown supporters have a direct, personal link to this space, as they may have family members buried there (or who have had their graves exhumed), or in some more indirect way feel connected to these few hundred acres. Other members are connected in a more spiritual way (adherents to Chinese folk religion, Taoism, paranormal societies). The arts community features heavily and plays a large role in organizing events: these artists range from those interested in the cemetery’s ceramics legacy to members of Singapore’s critical arts/art-activist community who often coordinate outdoor gatherings and performances. In this loose network of supporters are also people just taking part, such as tourists – who may have found out about the site via blogs, social media or travel sites such as Tripadvisor and may only visit the site once. These accidental, temporary members of the network who may only join briefly – by ‘liking’ a Facebook page or post, writing a Tripadvisor review or recommending the site to another tourist – are nonetheless part of the crucial ‘glue’ holding the wider movement together because of their ability to spread awareness outside of the City-State.

‘Save Bukit Brown’ has gained attention from the national and international press, as well as from organizations such as UNESCO and the World’s Monuments Fund which put Bukit Brown on its ‘Watch List’ (WMF 2014) and has closely been monitoring developments there. Tripadvisor, the travel site, listed Bukit Brown as a top attraction in Singapore (13 out of 318 reviewed attractions, as of August 2014) with all but two reviews as ‘excellent’ or ‘very good’. The inclusion of the cemetery on the World Monument’s Fund’s ‘Watch List’ (as well as the hundreds of Tripadvisor reviews) has fuelled a counter-movement of ‘guerrilla tourism’. While the state promotes the Botanic Gardens, the grassroots asserts its right to heritage and the historical commons.

A walk through Bukit Brown (instead of the Botanic Gardens) may thus be interpreted as being a guerrilla tourist, and simply by crawling under vines and over old gravestones, a visitor performs resistance and contestation (albeit perhaps unconsciously) by going ‘off the pathway’ and making the effort to find the tucked-away, hard-to-find cemetery entrance. I myself attempted to be a guerrilla tourist by walking in Bukit Brown. On one occasion, I walked around the paved pathway that encircles this site, with a colleague that I brought for company.

Place: Bukit Brown Cemetery (Singapore)

Date: February 2013

Time: 3 p.m.

We did not talk; we observed the birds in the trees and felt the humidity of the afternoon paste our T-shirts to our chests. When we saw a grave of interest, we walked up to it and tried to interpret the rich carvings on it, which are often Confucian fables of filial piety. We were observers and participants, and in some ways also activists. By being here, taking pictures and writing about it, we were helping to raise awareness of this site and helping to protest its destruction. We were not in an air-conditioned mall. We were not at the Singapore Botanical Gardens. Therefore we were not doing what we were supposed to be doing, according to the official narrative and expectations of tourism promotion authorities. We were transgressing. I noticed on the one hand how meticulously arranged the graves were, in feng-shui orientation, in neat rows. On the other hand I noticed now messy and jumbled this space was: vegetation had crept across the gravesites in a whirl of vines and giant banana trees.

A woman on a horse came by. She was a member of the Singapore Polo Club, which is located nearby, and often uses the cemetery to exercise the horses. She was part of the eclectic network of people who uses this place, allied to the resting dead, the angry activists and, for a moment, to me. Other members of this loose network, observed on this and other research walks (at different times of the day), include what I have termed spiritualists (who come to connect with their ancestors); gamblers (who come at night to ask for favours from their ancestors); Chinese family members (who perform Qing Ming and other graveside ceremonies and offer gifts to those deceased); tourists (the American couple walking ahead of me, holding a map and taking pictures, who may have heard about this place from Tripadvisor); joggers (who take advantage of the traffic-free pathways and rolling topography); activists (in ‘official’ groups, such as ‘Save Bukit Brown’); environmentalists (who are concerned with the loss of habitat for endemic species, including birds and monkeys); artists (who help to run tours of the site and also represent Bukit Brown in their art, ranging from photography to abstract displays at the museums); academics (such as myself, and staff members at the National University of Singapore, who now use Bukit Brown as part of the core Geography curriculum); and ghost hunters and paranormal investigators (who come at night, in the dark, and try to connect with the non-living).

Conceptualizing Bukit Brown as an activist and counter space (and guerrilla tourist site), I point to Foucaultian notions of governmentality (see Foucault 1991), and thus present Bukit Brown as a non-governable space within a highly-governed island. In Rose’s (1999) conception of ‘governable space’, power operates largely through the creation of spaces as ‘a matter of defining boundaries, rendering that within them visible, assembling information about that which is included, and devising techniques to mobilize the forces and entities thus revealed’ (p. 33). These spaces, in turn, ‘make new kinds of experiences possible, producing new modes of perception . . . they are modalities in which a real and material governable world is composed, terraformed and populated’ (p. 32). And thus, ‘the creation of governable spaces is also the creation of governable subjects’ (ibid.).

Envisioning Bukit Brown as a non-governable space, we can also propose that those taking part in ‘Save Bukit Brown’ are non-governed subjects, free to assemble in strange and novel ways that are not possible elsewhere in Singapore (and are certainly not possible in ‘official’ tourist spaces such as the Botanic Gardens). Bukit Brown then becomes more than a cemetery: it becomes the most open space of outdoor activism in the City-State and a site of possibility, a spatial rejection of the glossy promotions sent out via official tourist channels. Therefore it is also, by proxy, a rejection of the authoritarian power structure.

However, one may ask whether Bukit Brown is truly ‘ungoverned’: it is also a bounded space with many limitations and impossibilities. Despite the protest movement and small concessions and compromises from state planners (such as the construction of a ‘wildlife bridge’ over a stream), destruction of the site is continuing. Construction equipment invades more of the site each day and policy-makers have not changed course significantly, with plans to turn the entirety of the site, eventually, into an urban extension. On a return visit in 2014, I found the cemetery almost unrecognizable due to construction barriers and fencing.

An even bigger (and perhaps more controversial) question also emerges: is ‘guerrilla tourism’ itself an externality of privilege, the domain of those with time, resources and the intellectual and cultural capital to make a hobby of visiting ‘out of the way’ places? The social media and Tripadvisor conduits through which ‘Save Bukit Brown’ resonated are the domain of a particular subset of the populace – as Habermas (1989) described the (then emerging) digital realm as part of the ‘bourgeois public sphere’ which is ‘privately owned and operated for profit’, and in which ‘subordinated social groups lack equal access to the material means of equal participation’ (in Fraser 1990: 64–5). Migrant labourers, for example, are not part of the network to save Bukit Brown. They are, however, part of the construction teams involved in its destruction.

The campaign to save Bukit Brown also raises other important questions, e.g. what is more important – housing for Singaporeans (at a time when the cost of living is higher than ever) or a historical green space? What happens in real-world situations where the ‘right to the city’ clashes with the ‘right to cultural heritage’? For many Singaporeans, Bukit Brown is simply too abstract and removed from daily life to become an issue, or place, capable of resonating with the majority of the population and mobilizing a critical mass to push for real change. One research participant interviewed in December 2012, a satirical local author, summed up how he thinks most Singaporeans feel about Bukit Brown, based on a number of conversations he had with friends on the topic: “What do I care! It’s just a cemetery, they’re all dead, right? I’ve got my rice bowl to think about! I’ve got my house to think about! I’ve got my car payments to think about! I don’t give a shit about the dead people.’

The Bukit Brown campaign then cannot be considered a grassroots victory, but rather a focus of micro-victories: connections have been made between tourists and a wide group of normally unrelated activists (and non-activists) that may outlast Bukit Brown itself. The ability of Bukit Brown to galvanize attention internationally, and also across the ‘planetary scale’ of digital space (Merrifield 2013), tells a wider story about the potential for tourists and tourism to link with activist networks coming together around other issues (and other material places) in Singapore. Even though the movement has failed to save the cemetery, it was able to slow construction long enough for thousands to visit the site that would not have otherwise visited. The movement also induced an important conversation about how Singapore will deal with its remaining sites of cultural history, perhaps giving rise to a permanently more critical, more aware local community. Activism with regard to Bukit Brown cannot be evaluated therefore based on ‘winning’ or ‘losing’, but rather the possibility that momentum will continue: whether, as Solnit (2005) theorizes, one cannot stop the ‘spring’ of activism once it has begun. In the hopeful words of an interview participant, a blogger and activist, in January 2013: ‘So even if they lose? The fight to save Bukit Brown – and it’s not really a total win or loss situation, there can be some compromise – . . . it creates the material for the art and literature to come. And the audience for it.’

Therefore, as the cemetery disappears, the compelling question emerges of how, where and in what forms the activism momentum will continue, and how it could impact other sites and policy areas in Singapore. Whether the ‘guerrilla tourism’ of Bukit Brown Cemetery is indicative of the Singaporean grassroots’ potential to truly induce transformative policy shifts is unclear, but it offers a hint of the tactics and strategies that can be used to open up space for a new debate.

Conclusion: the living versus the dead – ‘guerrilla tourism’ versus the authoritarian state

This chapter has conceptualized ‘guerrilla tourism’ as an extension of Michel de Certeau’s ideas on spatial practice, the act of walking itself as a form of transgression/resistance by charting new pathways within (and against) the hegemonic urban landscape (as devised and formed by state elites, planners and market forces.) In Singapore, where top-down master planning has an especially strong precedent (and the use of urban space carries authoritarian restrictions), the concept of ‘going off the pathway’ is a challenge, as are the contextualities of what ‘resistance’ and ‘transgression’ mean in a setting where the state owns at least 80 per cent of all land in a geographically limited small island. It is this unique political and geographical context that frames the understanding of ‘formal’ versus ‘guerrilla’ tourism in the City-State.

The case of Bukit Brown demonstrates the possibilities of ‘alternative’ tourist spaces in Singapore to take on roles as important sites of (deliberate and non-deliberate) activism and transgression. Bukit Brown also demonstrates the ability for ‘unofficial’, ‘guerrilla tourism’ to reshape the City-State’s self-identity and world image by forcing open a new narrative and inducing an alternative conversation. Capable of bringing together groups that may not usually encounter one another and allowing those groups to experience urban space and interact in an ‘ungoverned’ manner, Bukit Brown is part of a growing global momentum of alternative readings of urban spaces (and the reappropriation of the urban touristscape).

Tan (2008) has suggested that the ‘elitism’ associated with Singapore’s ‘global shift’ has pitted ‘cosmopolitans’ against ‘the heartland’ and threatens the nation’s social balance. I have proposed the Botanic Gardens as a material representation of the elite’s notion of what it means to be a global tourist city, whereas Bukit Brown Cemetery is representative of an alternative, hybrid cultural identity and heritage, born out of grassroots networks and ‘off the pathway’ tourist flows. ‘Guerrilla tourism’ in authoritarian Singapore is not merely capable of constructing new meanings about urban space, but also provides ‘prospects for a new political opening’ (Scott 2011: 316; Long 2013) within the wider context of global capitalism through the cultivation of a shared aesthetics of protest. As a ‘guerrilla’ site, Bukit Brown has allowed a coming together of popular sentiment that represents not only a connection to history but also a rejection of Singapore’s developmental, hyper-modern cityscape, as expressed by a blogger and activist interviewed in January 2013: ‘It is both the green movement coming together . . . [and] the idea that uh, you know, you don’t disturb my family’s grave . . . – it represents precisely this anti-steel-and-glass ethos that has been gradually gaining ground.’

UNESCO World Heritage Status has now been awarded to the Botanic Gardens, but will never be awarded to Bukit Brown as the cemetery melts into thin air. Nevertheless, the resonance of Bukit Brown Cemetery as a counter-site of tourism (and activism) may change urban planning debates at the top level in Singapore, to allow more space for collective conversations on the historical, built and natural commons – or the ‘Save Bukit Brown’ campaign and network will reassert itself in a new place, in a new form. The destruction of the cemetery has instigated the blossoming of a grassroots response that may increasingly seek to question – and challenge – the authoritarian tourist city.