GREAT. ARE WE ALL SETTLED? Fantastic. Tremendous. I can tell this is a good bunch. A tremendous bunch.

Words spilled tinny from the overhead speakers, a deep and ballooning male voice undercut by the squeal of outdated equipment. In the cavernous room, our bodies turned toward the sound in different directions: we didn’t know what we were looking for or where we would find it. It was a conference hall, bounded by movable beige walls and wine-colored carpeting, the carpeting dotted by little shapes that had gone blurry, diamonds and triangles with no points. Through the vents in my sheet I saw a tacky chandelier shining weakly above us, faint in the enveloping daylight. I shifted the eyeholes to try for a more complete view, but it was all parts and pieces: a white sheet or some dark gap cut into it, the graying carpet, the steep emptiness above.

Right. Now. Oh. Eyes to the front, please, eyes to the front. I’m right over here, folks. In the center. By the podium. Right in front of you.

The voice came from all around, but I tried to turn away from it and look toward the light. Turning into my dizziness, I found the brightness of the outdoors, rectangled through large glass panels. A breeze swayed the long, faded burgundy curtains hanging in front of tall plate-glass windows, curtains that must once have looked expensive, important. Now they were nubby with lint and the glass behind them was dusty from the outside, which made the things you saw through it look fake. Birds looked like an echo of birds, fat white clouds looked as if they were there to sell you fabric softener or air travel or health insurance. And there at the middle of it all: a plain wooden podium with angled microphone, an averagely tall man covered in what looked like a standard-issue white sheet but was actually of a luxuriously high thread count. He shuffled in place—or maybe he was doing something more impressive, it was hard to tell beneath my covering. Besides a small patch of color below his eyeholes, an insignia that I had been told stood for his decision to renounce his mouth, he lacked obvious markers of authority. Even with his features and limbs hidden beneath loose white, he gave the impression of being overweight and soft, a body like a sofa. Great, okay, said the voice, which I understood originated in front of me but which seemed to come from all around, pushing from the outside in. Let’s begin. Greetings to all of our new recruits, and Welcome. Or should I say Unwelcome. I’ll explain that later. I’ll be your Regional Manager, reporting to the General Manager and by extension to the Grand Manager himself.

A few scattered claps that faded on their own.

You are all here because you have seen through the falsity of your everyday lives. You’ve seen that there is something real beyond the appearance of better and worse, buying and selling, brother, sister, husband, wife. You’ve seen that there is an arrangement of Darkness and Light that, like a shadow cast upon the wall, gives an illusory coherence to our lives and bodies. Or to put it in a friendlier way: You folks understand that there is more to life than life itself. Namely, there is Nothing.

Here, the speaker paused and I gathered that something was supposed to happen. I looked around me at other swiveling heads. Behind me, someone whispered a question. “Do they mean there isn’t anything, or that there is something and it is nothing, with a capital N?” they asked, and fell silent again. From the silence there rose the sound of a cough and a couple of people clapping experimentally toward the back of the room. He nodded at us. The applause swelled. Our speaker raised his hands to indicate that we should be quiet.

We are gathered here to begin a journey of self-discovery, that is to say discovering what is inside yourself. Is it good? Or is it a toxic sinkhole, poisoning those around you? We’ll find you out. Together. Here at the United Church of the Conjoined Eater, we believe that there is nothing more hazardous to yourself than being yourself. That burden should be shared. We believe that the quickest route to self-improvement is self-subtraction. Shed those unsightly remembrances. We believe that you contain a perfect being of radiant Light within you, a ghost that you were meant to become. You aren’t yourself, more and more: and we can help you achieve that. Any questions?

I looked all around me, pressing my hands to the sides of my head to hold my eyeholes on straight. I had questions. There were still some things that remained unclear to me. But scanning the room, I saw only nodding bodies, white lumps bobbing at the top ends of people who all seemed to understand what was happening. I looked back at the podium and nodded my own head in turn.

Great. That’s great. Let’s move on. There are only a few simple rules here, all designed to keep you folks safe. First rule: You show up at staff meetings on time and ready to participate. That means volunteer your own experiences, ask a good question, or just stand up and applaud someone who deserves it.

Second. There are no changes to your partner assignment. No way, no how. When you file out of the conference hall you’ll be given a room number. This is where you’ll be staying. There’ll be another person staying there with you. Perhaps they will be there when you show up, or perhaps you will be there for them. This person shall be your right hand for the rest of your time with us. Can you change your right hand? You cannot. For all you know, they might as well be you. Remember: Conjoined.

“HE WHO SITS NEXT TO ME, MAY WE EAT AS ONE!” shouted a fragile young female voice at the far right end of the room. More applause, and louder, one person whooping tentatively. I joined in, even though I could not say that I knew what I was clapping for, only that it seemed hopeful. In the midst of this new and mysterious information, I felt a confusion that was unlike my everyday confusion. It was the confusion of a newborn thing learning how to live.

The last rule I have for you today will probably be the most difficult one. In the life you left behind, you were asked to remember everything: your wife’s birthday, your husband’s preferred brand of soap, your best friend’s boyfriend’s name. Now we are asking you to unremember, as quickly as possible. This means unremembering not only your wife’s birthday, but your wife as well. This means unremembering what you used to do for a living, what you used to own or wear. Most of all, it means remembering only what we have here within the Church, objects and people of verified Brightness.

I felt my sheet jerk across my face, blocking my vision. Someone was tugging on it, trying to get my attention. I turned right, readjusting myself, to find my eyeholes exactly level with a pair of eyes, brown like my own. Height like my own, body like my own. I had a strange, excited feeling that I had found myself: I was real, I was really there. Then the voice of a full-grown man came muffled through the front fabric that was his face.

“What do they mean, ‘unremember’?” he asked, his voice urgent.

I pointed at the podium to say that he should listen, it would totally be explained.

“Do they mean forget?” he asked.

I shrugged from under my sheet and pointed again. Other sheeted people were glancing toward us now, swiveling their heads or tilting their bodies around.

“Because I don’t know how to try to do that,” he said, sounding increasingly upset. “I mean, I could stop talking about it, but I couldn’t stop knowing. I couldn’t do that. Nobody could do that.”

He grabbed my arm and I shook him off.

“You’re nothing like me,” I said to him loudly, so that everyone around us could hear. I wanted them to know: though we may have looked alike with our white sheets and brown eyes and same heights, I was made of a wholly different kind of material. He was in Darkness, groping around for what these rules might mean. Now that I was here, now that I had escaped myself, I would be Bright. I would do the rules to the letter, no question, and their meaning would become apparent as I saw what they made of me. In all my life, I had never known what life demanded of me. Now that I knew, I would do it even if I didn’t really understand what it was for.

It means unremembering the capitals of states and the denominations of currency and the nuclear power plant. All our troubles began with the power plant. It means unremembering anything made with chicken, which is a highly toxic Dark meat: even thinking about this substance can cause irreparable harm to yourself and to those around you. And most of all it means unremembering yourself: waking like an amnesiac to a world beauteous in its unassociations with pain, worry, strife. When the world is clean it shines Bright in its blankness. When the body is clean it rises ghostly into the Light.

I looked around for the man who had accosted me, but he was lost, reabsorbed by the throng of sheets. His questions had made me miss something in the Manager’s speech, something I didn’t know how to get back. Maybe I could ask my partner what I had missed, what other dangers I needed to avoid. Maybe my partner would be nice and not remind me of anything dangerous. Then the applause broke out all around me, loud and unhuman like the waves or the rain, and it was a moment before I remembered to join in, flinging my hands together in front of me, clapping until they hurt, trying to create in real life the small picture of an ideal Churchgoer that I had in my mind.

As we thronged from the room, sheets dragging across the carpet, someone stopped me and gave me a slip of paper that read E38. “Your room assignment,” she said, her voice upbeat but not inspiring confidence. As I filed out the doorway into the corridors beyond, I saw a slight, sheeted figure up by the podium being reprimanded by the Regional Manager. I couldn’t help thinking it was the man I had met before, the man who was my size, the man who made me miss that key part of the speech I needed to become the ideal person I had come here to be, a person who wasn’t.

IN THE HALLWAY OUTSIDE THE conference room, it was easy to pretend I knew where I was going: I followed the others, who filed unanimously toward a tight, cramped back staircase painted a nostalgic shade of mint. We were all new intake, fresh bodies for the Church to process, but as far as I could tell I was the only one who didn’t know the layout of the building. The others navigated it by instinct, down flight after flight of stairs, taking the sharp turns of the staircase with ease, while I let my body get pushed along by their collective motion. I couldn’t understand how they knew what to do—it was the first day and I had already fallen behind. The crush of bodies was a slow river of white, crowding our way to the goal. It reminded me of something I might once have seen on a nature documentary, the spawning of sharks or salmon.

We skipped one unmarked entrance after another, then suddenly the sheeted bodies were passing through a blank doorway painted glowingly green. In this new, subterranean corridor our unified motion disintegrated. Eaters split off to look for their assigned spaces while I pressed my back against the wall, trying to breathe, trying to fake a type of composure that would indicate that I was brimming with Light, quick to shake off the Darkness. It was while I hid here, in plain sight, that I began to notice that there were other Eaters like me who were not adjusting well. There in the midst of a traffic of white, they stood frozen, staring ahead of them or covering their eyes. Backs hunched, heads down in their hands, they looked as though they were wishing themselves out of this place or mourning their lack of know-how. Some came out of their stupor on their own and headed casually to their quarters; others were collected by low-level Managers and led away.

Then I saw a flash of skin in the white throng and some blue and green. In the sea of white, these colors looked wrong, a stain that was somehow moral. It took a moment for the colors to resolve into the shape of a human being, but when they did I recognized him instantly as one of the Disappeared Dads I had seen on TV. He had vanished while watching his eight-year-old son playing soccer in the park. He wore a green plaid button-up shirt and blue jeans, and he was pacing around the crowded floor with his left hand in his pocket and his right hand up to his ear as though he were talking on a cell phone. “No can do, no can do,” I heard him say out loud, again and again. He looked the same as he had on the news, only his face was vividly pink.

As I watched him talk on his imaginary cell phone, I saw a pair of Managers come up next to him, sheeted up in coverings that bore the shape of the Renunciation Mouth. They spoke to him, poked at his exposed flesh. Their voices were muffled, but I could tell they were trying to get him to put his sheet back on. “No can do,” he said. “I gotta be comfortable. I gotta be comfortable. No can do. Have you seen my slippers?” They looked at each other and grabbed him by the arm. Gently, firmly, they pulled him out of my sight, into the crowd beyond.

I looked around and saw a girl next to me, who had been watching them, too.

“Did you see that?” I asked.

“No,” she replied.

“It was one of the Disappearing Dads,” I said. “Hank. Or something.”

“I don’t think we’re supposed to remember that,” she said, sounding nervous.

“Where do you think they’re taking him?” I asked.

She shook her head.

“Do you know where E38 is?” I asked.

But she was already walking away.

BY THE TIME I FOUND E38, my partner was already inside waiting for me. I had expected a room, but what I found was more like a medical examination tent, set up within the larger central space for emergencies. Instead of walls we had curtains: deep red curtains made of cheap velvet, strung up on metal rods that shook when someone heavy walked by. There was a small collapsible table and a rolling rack for holding an IV or a coat. A steel-rimmed mirror in the corner turned out to be a to-scale painting of the curtains, so that you stood in front of it expecting to see yourself, and instead you saw Nobody. One double-size cot done up in stiff red sheets sat in the center of a room that was barely larger. A girl lay atop this cot, sheetless and splayed out in the center like a starfish, so that she took up roughly the entire space. She lifted her head and glared at me.

“You’re late,” she said.

“I got lost,” I said.

“How could you get lost?” she asked. “We got directions at the meeting.”

I thought about explaining the guy, the guy who made me miss part of the speech, but instead I just shrugged.

“I’ll help you next time,” she said. She peered into my sight holes and added: “It reflects badly on us when half of us is late.”

I took in her small, heart-shaped face, the pointy chin, the dark hair cut in a long, blunt bob not all that different from my own. She had dark brown eyes like mine and skinny, fragile-looking arms. In a taxonomy of women we would have been side by side. I wondered if she was pretty: I was so far from remembering how that concept worked and what it looked like. I wondered if she was prettier than I used to be.

“Shouldn’t you be wearing your sheet?” I asked.

She looked at me strangely again.

“They explained that, too, in the speech,” she said. “Were you even there?”

“I was there,” I said. “But a Dark person in the audience interrupted my access to the information.”

“Okay,” she said. “I’ll explain it, but you need to avoid situations like that in the future. Every interaction with Darkness brings down your Light levels, and you can pass it on to me too because we are One Person.”

I nodded, and she explained. This small shared space was the only place in the Church where we were allowed to appear uncovered, sheetless, our sticky limbs exposed to the air. This was for some or all of the following reasons: The fabric that shielded us from rays of Darkness also interfered with the production of vitamins that we needed in order to keep living, at least until the day when our living was complete. Or our bodies needed to see another body every once in a while, see their naked face and little white teeth, to remind ourselves that we were not yet ghosts, only flesh pointed toward that goal. Or the sheets were primarily a way of communicating, we needed them only in the gathering places as a statement made to one another that knowing one another even as little as we did was a temporary situation, bound to end soon. Ultimately, seeing our partner sheetless helped to erode our memory of our own particular face, which was unviewable within the Church owing to the lack of mirrors.

I pulled the sheet up over my head and let it fall to the floor, crumpled. It was a relief—to pull the sheet from my body, to peel it from me where it had fused to my skin and yellowed, to expose my tingling arms to the air—but somehow it annoyed me to show my face to this strange new girl. She reminded me of B, consuming my face with her eyes, thickening the air with her presence. To see her lounge around in her skin as if it were the only natural thing to do highlighted how unnatural anything was for me now. I decided to call her Anna, which wasn’t so far from my own name. It was palindromic, which seemed to suit someone who was destined to become my mirror. It was short and easy to remember. It was the name I had given to my favorite doll, the one that I asked my mother to throw away after I noticed something overly human about its eyes.

My hair clung to my skin like a bark. “You look exhausted,” Anna said, sitting forward on the cot and looking at me hard from both eyes. “Much more tired than me. I’ll work on getting my face a little bit wearier, but I always tend to sleep well. I think it would be better if you’d work on getting some more rest. The closer we are in body and appearance, the easier it’ll be to merge our life.”

I didn’t say anything.

“If we are as One Person, spread out over two bodies,” she said in a pert, authoritative tone, “we’ll halve our load and ghost much earlier.”

“I know,” I said, but I didn’t.

Then from behind me I heard the sound of the curtain being pushed aside, and a dinner tray slid into our space, its contents obscured under a gleaming metal cover. I picked it up and looked out into the corridor to see if another was coming, but there was nobody there.

I turned back to Anna and told her: “There’s only one.”

“Of course there’s only one,” she said. “We share everything now.”

I looked down at the shining tray. I had no idea what it might be. A purer food, probably, or maybe a less pure one if they wanted to test our powers of distinction. I had to remind myself to keep my hopes down, that it might not be food at all—though the thought made my stomach ache with hunger. I took a breath and then I lifted the cover off the tray.

What I found there was a small heap of Kandy Kakes, twelve of them piled on a white plate. They were just as I had pictured them over the last few difficult months: a double squiggle of frosting-flavored icing gracing the dark, hard surface of its chocolate-armored puck. Just as I had pictured—only, if possible, even more beautiful.

I almost couldn’t believe this was really happening. I would grow clearer, thinner, Brighter, a more perfect vessel for my ghost. I felt a great burden lift from me, the burden of worry over what I was, what was becoming of me. With the help of these Kandy Kakes, I would finally become better in the Bright future ahead.

“Why are you crying?” asked Anna, annoyed.

I tried to explain: “I’ve waited so long for these.”

Anna shrugged. “Well,” she said. “Congrats.”

I picked one up and brought it to my mouth. Of all the things I had wanted in my life, these were the only ones left. I felt my body grow hot, then cold, then hot again: I wanted to cram them all whole into my mouth, force them down. I breathed in their scent of hard, waxy chocolate and stale orange. My throat was wet and wide and tender.

Then I bit. It was harder than I liked, the casing exactly as impermeable as the ads boasted. I shifted it toward the back molars, where my jaw was a little stronger, and managed to pierce the chocolate armor, crush it a little, so that the syrupy orange-caramel filling began its seepage into my mouth. The orange goo tingled with sweetness against my tongue.

I looked up and saw Anna watching me.

“It’s delicious,” I said.

She nodded and blinked.

As I took up my second Kake and third Kake and bit down through their Choco Armor, I tried to remember only this moment, this present moment that was continually ending, this moment illuminated by the safety and Brightness of the Church, but I couldn’t help it. Even though I knew it only harmed me, only hindered my progress, I was thinking of my old life, of the way B used to watch me eat. I’d be reading old sections of the Sunday paper while eating a bowl of cereal, and every once in a while I could look up to see her eyes on me. The look in them was something strange. She stared at me like I was doing something new that she wanted to do very badly. She stared at me like I had performed an ugly miracle. She stared at me like she’d be practicing it later, in her room, alone—standing in front of the mirror and chewing exaggeratedly, cowlike, biting at the air.

THAT NIGHT, I WOKE TO a feeling of hunger that verged on pain. I rolled over on my side and clutched my belly in toward my center, as though compressing the organ could fool it into thinking it was full. I sat up and looked at Anna, slumbering peacefully beside me in our double cot. I needed to eat more, and I knew if I woke her, she’d talk me out of it. Anna found it easy to follow all of the Church rules. But as long as I was eating the approved food, I reasoned, it shouldn’t do too much damage to my Brightness levels if I ate another serving or half serving. I eased myself out from under the covers and put on my shoes and my sheet. I slipped out through the red velveteen curtains and snuck through the hall to a neglected-looking service elevator. Inside the elevator, the button panel was all blank. I pressed one at random and hoped it would take me to a floor with food on it.

Through miles of Church corridor, on floors where broad windows looked out on a massive parking lot, dark and featureless like this immense building’s even larger shadow, on floors that had no windows and thrummed with the sound of machinery far underground, I searched for food. The structure was clean like a hotel or office building, the carpeting clean and dustless, but there were things piling up in it that didn’t belong: a tilting pile of sequined decorative pillows blocking what looked like an unused elevator bay, cardboard boxes lined up in the hallway that turned out to be full of jars of beauty cream, the one with the commercial where the bird escapes from inside the woman. The creams were heavy and full, store-ready in their crisp red boxes, but when I took off the lid the cream’s surface had a deep swirl in it: not a machine’s smooth finish but something made by hand.

The upper floors had crisp steel numbering and panes of cold glass that revealed dull gray interiors. In the middle, the halls were motel-colored, sullen beige, with smooth neutral doors marked by small brass numbers. The lowest levels of the building—where I wandered, hiking my sheet up to move more smoothly, hoping to find a familiar letter on a door, or any letter at all—looked like a series of bunkers, avocado green and overlit, the signage on the walls outdated and peeling. Each new part of the Church I saw made me think it had once been something else: a hospital, a corporate hotel, an office complex. Even stripped of its former contents, the deep structure of the building held traces of its former use. I wondered if the other Eaters who passed me by could tell by looking at me what I had once been, what I had once bought, what couple of categories I had once belonged to.

On floor six, a tall man under an extra-long sheet with a ragged hem stopped me in the hall.

“What are you doing in Section Six?” he asked, holding me in place with two fingers on my sternum.

“I was just looking for some food and I got lost,” I said.

“No additional food,” he said flatly. “Where are you supposed to be?”

“E38, I think,” I replied, thrusting my scrap of paper out from under my sheet and toward his eyeholes. He read it, turned it over, handed it back.

“Who gave you this?” he asked me.

“I don’t know,” I said. “Someone in a sheet.

“I’m new here,” I added.

He looked at me, blinking through his holes, and when he spoke he sounded as though he had decided to do me a kindness.

“You aren’t allowed here,” he said in a reasonable way. “You’re not cleared for it. These aboveground floors have a high minimum Brightness level. You won’t meet this level, if you ever do, until you’ve spent a good amount of time working down below.”

“Is there a chance I’ll never reach this level?” I asked.

“Not everyone reaches this level,” he replied. “More than half never leave the basement, until they are passed back out into the world.”

“I hope to go all the way to the top,” I said. To the final level, whatever that was.

As if he hadn’t even heard me, the tall man pointed at a stairwell down the hall.

“You need to go ten floors down,” he said. “Ask for E Wing. Don’t tell them you tried to sort yourself up within the building.”

I nodded, but I could see from the nonalignment of his sight holes with my face that he was no longer thinking of me at all. It made me remember C, how in his calmest and most relaxed state I could tell exactly what he was thinking about just by following where his head was pointed. By tracing his line of sight and fixing myself on that same TV show, crumpled sweatshirt, or cardboard pizza box, I could feel like I shared his mind, that our minds were one. I always wanted that intimacy, immediate but at a distance, as though our love were as swift and expansive as television.

I felt a sharp pain. Someone had hit me hard on the shoulder, I felt it down to the socket.

“Stop that,” the man said sharply.

“I wasn’t doing anything,” I said.

“You were remembering,” he said. “It was blatant. You put us all at risk.”

“It just reminded me,” I said, about to explain.

Suddenly he was backing up, pulling his arms in toward his chest so that his body under the sheet looked even more like a Halloween ghost’s, swaying slightly as he retracted his body, shuffling, toward the opposite end of the corridor.

“No,” he said. “No. You take that elsewhere. Take it back to the Darkness. We don’t want it here.” The smooth, round eyeholes, unchanged, contradicted the fear I heard in his voice.

He had almost reached the stairs. He turned his back on me to open the door and dove into the stairwell, slamming the door shut behind him. I heard the sound of his footfall on the stairs, running from me, fleeing vertically into safer and purer levels of the building.

I stood there for what might have been a half hour. My breaths were tiny, the air around me was still. I was afraid to move my body or my mind. I didn’t know what would happen if I began remembering again, but I could tell from the man’s reaction that it was something to be feared. C would have said this man was nuts, but I knew there was wisdom in his reaction. For as long as I could remember, there had been something going wrong in me: I did what I didn’t want to do, I wanted to do things that I knew I didn’t really want at all. Something in me did wrong when I needed to do right: the man who had fled was just the first person to see this in a tangible, physical way.

There was an uncontrollable amount of me within myself, and I didn’t know how to stop it. I had missed some key part of the Manager’s speech that explained how to unremember. Worst of all, I could feel it there inside me: my past. Even in its barest sense—recognizing a color, identifying a face—it worked Dark within me, before I even knew it was happening.

But then like a Bright gift, I recalled that a better me dwelled inside the me I was. I could feel it there, faintly: a version of myself with no past or present, just a feeling of Nothing about everything. Nobody else had seen me here in the sixth-floor hallway, so I would return to Anna and E38, eat the instructed portions of food, and try once more to live a life of genuine and luminous Brightness.

THE NEXT MORNING, ANNA AND I sheeted back up and went to our Church jobs, beginner jobs that were assigned to the newest converts because they didn’t require much specialized training in the dynamics of Darkness. We spooned beauty products into beauty product containers by hand, a task performed better—and less messily—by machines. Specifically, we spooned TruBeauty gels and creams into TruBeauty containers in a large, open room that looked like it might once have been a gymnasium.

The Church owned shares in TruBeauty and a few other companies, like the company behind Kandy Kakes and the furniture company responsible for the large decorative pillows that were piled in the hallways and workrooms. We could do a lot of good, they said, controlling the movement of Dark and Light goods across this country, collecting the Bright things in one place and the shadowy ones in another and then keeping our own bodies as far away as possible from the bad things. We could do a lot of good for the people of our Church, they said, hoarding them away from a dangerous and variegated world, bricking them in with a wall made of Light. And then there was a need to keep bringing money in for as long as we all still had physical bodies requiring physical food that could only be grown, stolen, or purchased at a store with government-issued American currency.

I looked all around the Spooning Room, a gigantic, light-flooded indoors that felt more like an outdoors, and tried to imagine how much money it meant for the Church. Surrounding me, sitting on the floor, standing, cluttering the glossy pine floors with the dragging ends of their cloths, were sheeted-up believers. They huddled around industrial plastic containers of face cream, body cream, eye cream, esophageal cream, scooping spoonfuls and screwing shut the lids. The room looked wintry and cold; frosty evening light fell a deoxygenated violet over acres of white. In the sky-sized space above our heads were pigeons huddled silent in the rafters, and from time to time one took flight from one side of the room to the other, casting a small traveling shadow over our pale, upturned faces.

All around me, other Eaters spooned vigorously, with a good attitude. I struggled with my sheet, trying to push the parts that were the most like sleeves farther up on my arms so that I wouldn’t get beauty cream all over my coverings. They slid down and I pushed them back up. I readied a bared hand for spooning and then I plunged my spoon deep into the vat. The hem of my sheet dragged in the gelatinous white and I pulled it out, wiped it off, readied my spoon again, and plunged it in, more cautiously this time. I filled one pot and then another with TruBeauty skin cream, the edible throat slickener that I remembered from commercials when I was still a Dark body, ghostless and clouded by misinformation. I remembered the bird, a white dove fighting its way into the woman’s mouth, scrabbling at her face with its small talons, grasping for a clawhold. How the woman tried to smile around its body, her mouth entirely filled, her jaw straining at its limit. And how B used to inch closer to the TV while it played until she was on her knees before it, fascinated, the blinding white of the bird and beautiful face turning her own face pale like a corpse. I shivered and rubbed at my skin.

I didn’t have to look up to know that a Manager loomed over me. I could tell from the hand that protruded from beneath his sheet, a hand gloved in white latex. He leaned over me and bent to examine my work. His long white sheet brushed against my face and clung to me there, where my skin was damp with sweat and sticky with the edible cream, which seemed to end up everywhere no matter how clean I tried to be. I saw his gloved hand come toward me, its finger a vague hook glistening in tight plastic. It stopped an inch from my cheekbone, hovered there. And then it came closer. He was scraping a patch of cream from my face, scraping it with force, and I knew that he was doing it not for the benefit of my face, but to see what was underneath. As he crouched down and peered at the spot he had excavated, I willed myself to think Bright and clear, to think only about my ghost and its pure yolklike perfection inside me, or about the wisdom of the lessons and how they confused me and twisted my thoughts into useless, harmless shapes, or about TruBeauty cream and how I should spoon it better and faster and neater and not think about how this same product had touched other parts of my life, Darker parts that I shouldn’t be thinking about. But there was Darkness in my thoughts, and I knew he could see it. I closed my eyes and imagined an egg. His breath had a curdled smell, it stuck to my skin. Suddenly he straightened up.

“You’re full of murk,” he said, speaking down to me from his full height.

I looked up toward his face, sought out the eye and mouth holes that swayed an inch or so in front of his actual face. At the edge of a hole I saw an eye I thought I had seen before, blue and watery.

“And you’re making a mess,” he added, swiping his arm around at the irregular blotches of beauty cream that marred the floor and stained my white sheet a thicker, heavier white. “Try being more like those around you,” he said as he walked away, “and less like yourself.” I looked around the room. Everyone else did seem to be doing a better job, a cleaner job. Then from across the room I thought I saw Anna sitting at a different spooning station; I recognized the frayed right corner of her standard-issue sheet and the smooth, lazy way she scooped, as if it were easy, as if she were only lying around in our room, staring up at the ceiling and practicing her emptiness. A Manager paused by her station and patted her back. She looked up at him as he looked down and they were both nodding at each other, nodding as though they had just made a decision together. I thought of B’s face pressed jealously against the window as she watched me walk away with C, my hand seeking around for his. Steering him away from her in the drugstore when I spotted her there, down on her hands and knees and reading the backs of boxes of hair dye. I thought of her face smiling out at me from under my haircut, and as I did I could feel my skin growing thicker, foggier, leathery tough. I couldn’t seem to stop it; the memories came uncontrollably. I stopped spooning, squeezed my eyes shut.

When I opened them, it was to the sight of a tall, heavy-looking Eater in a newcomer’s pristine white sheet. He was wandering back and forth on the warehouse floor, stopping other Churchgoers, grabbing their shoulders, and shaking them gently, asking again and again: “Have you seen my car? A green hatchback. Have you seen my car?” I looked at the spooners around me. We had all stopped spooning, all turned our faces toward this alarming man who, in his forgetting, seemed somehow also to be suffering a seizure of remembrance. I could see on all of their faces that it was uncomfortable to watch him suffer so from his own unsheddable Darkness, but I felt worse than the rest of them. I knew I was closer to becoming him than becoming the well-adjusted Eaters to the right and left of me. I knew I was only a few remembrances away from letting something Dark slip out again.

As I watched, the Managers surrounded the remembering man on all sides. “Have you seen my car?” he asked them as they closed in on his bulky body.

The Eater to the right of me must have seen my concern through my sight holes. She leaned toward me in a confidential way.

“The Dads usually burn out early,” she whispered. “Nobody knows why. Some people think it’s because they can’t shed their memories properly. They’re too tied to the things they were responsible for, the things they owned. Even though that’s what they came here to escape.”

I looked at her and nodded. The Managers were dragging the man off toward the warehouse’s outer door. The man had stopped asking about his car and was now just sobbing blurrily, a wet patch forming on his sheet near the face and shoulder.

“What happens to them?” I asked quietly.

“They are expelled,” she said matter-of-factly. “Banished to their former lives. Returned to the toxicity of the world outside. You cannot have those kinds of things going on around purer, Brighter people. Allowing them to stay, even in a separate area, even in a neighboring building, would hold us all back.”

I looked out at the outer door, glass paneled and sleek. In the squares that opened up onto the outside world, I saw thousands of small leaves twisting in the breeze, the worn gray asphalt and curb, empty plastic bottles and cans sitting in clods of browned-out grass. I saw at least twelve different things that I knew were killing me at varied rates, driving me insane, rendering me toxic and flawed. A shiver ran down my spine. Whatever it cost me, whatever it might take, I had to stay in the Church.

I WAS STANDING IN CONFERENCE Room F waiting for the day’s speech to begin, waiting for our Regional Manager to step up and give us the day’s new lessons on what to avoid, what to remember, what to forget. Anna had offered to stick close to me and explain the nuances of the speech so I wouldn’t make so many mistakes in the future. “Every slipup of yours causes me to slip too,” she said. “Remember that.” I knew now that I had to follow her instructions to the letter if I wanted to stay in here, where I was safe from the Darkness and the toxins and, most important, from myself.

It was late afternoon and we still hadn’t had lunch; people stirred a little less than normal as they stood. They moved drowsily, their sheeted forms tilting in the light like there was a person trying to keep awake somewhere beneath. From across the parking lots that darked like lakes through the middle of the business center, we saw other buildings like our own, mirrors to those on the outside, and we saw small people entering them and leaving them.

In the room, a scent like diet cola sweated from our bodies, sweated out through the skin and was absorbed by the white fabric. The sound of a generator weighed heavy in the air, filling the room though all the windows were closed. Light filtered in through the standard-issue sheet I had been done up in, through the very transparency of the cloth itself. We knew we were safe in here, or we thought we were, or we felt we were, or we wanted to feel we were. Through eyeholes I watched my fellow Eaters, the white of their coverings melding together to form a thing that looked like a mountain range in the snow, dozens and dozens of peaks rising sudden and urgent from out of the white, the points eerily rounded, as though they had been hammered down.

We were packed tight together and the air tasted moist and personal, like a kiss from the mouth of a stranger. Dozens and dozens of us, new and old, waited restless before the empty podium. We swarmed it like ants around a gob of jelly, trying to figure out how to wring from it the thing we wanted: a glimpse of the Regional Manager, the Manager’s favorable attentions, the words from his mouth that raised us from our situation and into a better one. These blank periods of time before the lesson began were difficult to fill. They were uncomfortable and boring. We wanted to watch one another, judge one another, determine whether we were better than each other and worthier for advancement. We wanted to feel lucky, feel hopeful, feel closer to our ghosts. But in this sea of white, it was hard to see any trace or trait on your outside that made you different from anybody else.

The white mounds in front of me begin shifting, turning their torsos laterally beneath their shrouds to look around, swaying before me like mountains in the wind. Then I see our Regional Manager making his way through the crowd, cutting his path from the catering entrance toward a thick swath of admirers who part just a little to let him through. They all want to feel the force of his body on its way, they think that some of his Brightness will rub off in the friction. The Manager, trailed by a couple of assistants, grasps his head with both hands to keep the eyeholes in place as he moves. He’s walking slowly, like he thinks he has a majestic air. But he’s not that tall, not especially graceful. All he is is Bright, Brighter than the rest of us. We know this because we’ve been told, we know even though it doesn’t really show up through his sheet, a sheet of higher quality than ours—hotel-quality luxury thread count, thick and creamy with satiny details at the hem that drags along behind him. He reaches the podium and his assistants scurry out from behind to sort out the train of his sheet so that he won’t trip as he turns to us to speak. The Manager gives us all what I assume is a look of appraisal, though through the eyeholes it can be hard to tell. At moments like this he looks so ordinary it is hard to believe that he, alone, has the knowledge necessary to midwife our future selves.

Then he raises his hands grandly and addresses us all:

HE WHO SITS NEXT TO ME, MAY WE EAT AS ONE!

I look at Anna, standing next to me, already shouting the words back to him, already joining her voice to the total volume of the crowd, shouting and shouting in perfect unison like one great white sprawling person with a single monstrous voice. Anna looks so happy through her sight holes, her eyes bugging out enthusiastically, her mouth pressing feverishly against the inside of her sheet as she cries out again and again. She looks so happy and so Bright.

I reach down and I take her hand in my own. I clasp it. I work my fingers in between hers and twine us. And then I lift my head up to shout.

INSIDE A BODY THERE IS no Light. Blood piles through with no sense of where it goes, sliding past inner parts, parts that feel something but know nothing about what they feel. What they sense they send up through nerve channels to the brain, a cavefish-pale organ with no nerves of its own. Inside a body, thoughts that never touch air, never reach Light, thoughts that end in a suffocating Dark. The damp basement in a horror movie into which a teenage girl sinks slowly, the stairs groaning beneath her weight, her voice thready and red as she says the name of her boyfriend out loud, over and over again.

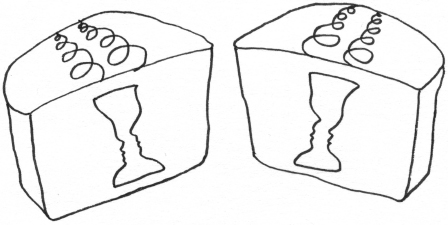

Inside a body there is no Light, so the Eaters teach that you must shine your own through Righteous Eating. The diagrams illustrate it beautifully: a female torso in cross section, set on its side like a fish on a cutting board. Small cubes of black and white fall down its throat in the direction indicated by an arrow, the paths of the body marked out in bold white lines, highway lines. These black cubes represent food, the bad kind that starves the ghost within you so that when it is its moment to emerge from your soft shell, to come from you into the world and carry out your project more perfectly than you had ever dreamed, it will die trapped and weakened in your body that has been a prison to it forever. White cubes are the good kind of food, the kind that can save you—if not in this body, then for the next.

Inside the schematic woman, food cubes are destroyed. They release their own benevolent and malevolent ghosts. Dark food travels down to the protective organs in which the ghost gestates vulnerable and sleepy; it clusters to their outsides and strangles what sleeps within. The good food, by contrast, breaks into shafts of differently colored light, bright like fireworks, and this light illuminates the body and nourishes the ghost within. Imagine this, they say, how radiant you become when you eat Bright. How beautiful, how durable and long-lasting. The colors that can’t be seen, working brilliance inside you, preparing you for your ghosting. Colors more beautiful than any of the colors you know.

I used to lie in bed at night with my hands on my belly, feeling the blood crowd through, wondering what was taking place within me. Now that I had been illuminated, I lay in my cot, sideways like a baby in the womb, and when I rested my hand over my central organs I knew precisely what lay beneath. I knew that the flawed and sad feelings, daily dissatisfactions and pangs of despair, were just my ghost’s way of kicking within me, kicking to test its independence, kicking to tell me it wants to be let out.

I fell asleep dreaming that it would split me open someday soon, like a green shoot piercing the husk of a soiled bulb.