WHAT WAS AT THE ROOT of Disappearing Dad Disorder? Sociologists said it was social, psychologists said it was psychological, and some religious nut said they had heard a call from God to leave behind their wicked lives. Biologists compared it with migration and with songbirds that become confused in the presence of skyscrapers. They compared them with honeybees who abandon their hives: maybe the fathers had been misled by cell phone signals, by highways, by toxins in the water supply. An American studies professor from Cornell argued that it had to do with the breakdown of the single-earner family model upon which our common baseline for masculine worth was founded; a comedian said that all husbands were on the verge of disappearing, only there was still such a thing as a football season, and then a basketball season, and then a baseball season. And a minority voice pointed out that this had been happening forever in minority communities, but it wasn’t called a disorder until it started happening to well-off white people.

Possible explanations for the self-napping impulse were offered up in interviews with abandoned wives. Their husband was a sneaky rat and had been since the earliest days, the days when they were courting and he often “forgot” his wallet, forcing her to pay for the entirety of their meal, which, though it was only diner food—fast food, really—nevertheless added up. Their husband was well intentioned but also a doofus, he had trouble with navigation even in their own moderately sized gated community; his absence was surely an exaggerated case of the many instances in which his sense of direction failed completely even as he continued to insist upon its “pinpoint precision.” Their husband had loved them very much, particularly in the beginning, but in recent years she had noticed that he had noticed that the backs of her arms jiggled when she waved hello, that there were spots that were not freckles distributed among her freckles, that her joints made loud cracking sounds when they made love, which sometimes caused him to ask her if she was all right.

But maybe the fathers were just seeking a perfect life, which when you think about it is a completely reasonable thing to do. They wanted the good things: the popcorn, the corn dogs, the plush industrial mall carpeting with its friendly geometric patterns screaming themselves in green, pink, and brick red, stretching across the concourse like a little, comprehensible fragment of infinity. They didn’t want the bad things: the pressure, the stress, the weekly division of chores by chore wheel, the homework that they thought they had done away with when they graduated elementary school or middle school or high school or business school. They didn’t want the gift-curse of recognition by those they loved and who loved them back, one consequence of that love’s durability being that they would be recognized and loved aggressively even on days when they couldn’t stand to recognize themselves in the mirror, even on days when merely remembering themselves made them sad and want to sleep. Love that made every day a day that they had to live in a handcrafted, artisanal fashion, rather than being outsourced to someone who could do it happily and efficiently for a third of the price.

They might have thought, to use a stock phrase, that somewhere out there was a way to “have their cake and eat it, too.” That many of them returned to their homes months later, malnourished, dehydrated, and amnesiac could be interpreted as evidence that there is no cake anywhere in the world to be had or eaten.

THE LIGHT WAS EBBING INTO my room from the west, a swath of rose coating the surfaces before dying off for the night. Without my contacts, things bled into each other, the differences between them middled. The first day that I ever understood my eyes were imperfect, my second-grade teacher had called on me to read what was written on the board at the front of the classroom. “What am I supposed to read?” I asked over and over. The board was a flat green, marked only by a smear of chalk dust. The teacher threatened to send me to the principal’s office, but I was brought to the nurse instead. There I was made to understand that there were things I didn’t see, things I very likely hadn’t seen for some time. There were messages embedded in the blur. In my room, the late light evaporated the bookshelf and mantel, retreating into the dusk.

At the corner where I kept some of my cosmetics, I imagined myself standing there, my body small in the space surrounding. From the times I had seen my reflection without preparing myself, I knew how bad my posture was, how I let my shoulders fall forward, making the chest look caved in and weak. But the self I projected in front of me looked alert. My neck looked long. I was looking through the clear resin box that held the little makeup boxes and tins as though I had not seen them in a long time. I felt pleased with myself. I felt that I was a girl I would enjoy watching as she went about doing the little, dull things that make up a day. That’s why it was so alarming when I realized that instead of pretending to watch myself, I actually was watching B.

“What are you doing in here?” I asked. “Didn’t you see I was sleeping?”

She turned her blur of a face around toward me. I was trying to get my contacts in as quickly as possible, to decrease the resemblance between us by increasing the number of details I could discern.

“You were sleeping. And I already asked you if I could use your makeup,” she responded.

No, you didn’t, I wanted to say. You didn’t ask.

Instead I groaned and pressed the covers to my eyes, which hurt for some reason.

“Can you just get out?” I said. “I need to wake up.”

B left, letting the door swing halfway shut. Without my contact lenses I couldn’t tell how she had meant it, whether her exit was guilty or reproachful. I rolled back into a sleeping position with the covers bunched in front of me like another person, which I held in my arms from behind. I missed C, but I was weighing the possibility of getting caught if I tried to leave to go see him. I thought about staying here in my bedroom for weeks, until she forgot about the whole makeover idea and moved on to something else I would have to do for her. I could wait it out.

With the two and a half packs of cookies I had in my desk drawer, the three oranges in my dresser, and that bottle of wine I could make it two days, maybe three. But if C brought me groceries and hoisted them up through some sort of basket-and-rope rigging, I could make it for weeks, conceivably. Maybe three weeks, if C didn’t forget about me or find someone new. B would give up long before that. She would find someone else to get close to, someone like me with an open room in their apartment, or maybe she would move out and get a job. It could be exactly the push she needed to step out into the world and take her place as a productive member of society. And I could walk out years later, fresh and rested, into an apartment that had been occupied and abandoned again and again, occupied and abandoned enough times that my name and story would have become legendary and then been forgotten several times over.

But if I was in here alone for weeks, C would forget about me, too. I could sneak him in through the window for visits: there was a fire ladder to the roof on one side and a large tree on another. My last boyfriend used to come up like that sometimes to be cute. The noise he made when he knocked on the loose panes of the window was terrifying. But C wouldn’t climb the tree because he wouldn’t support my desire to stay forever, together, in my room. He’d argue with me, probably, from his spot on the ground, and in doing so, he’d completely give away my hiding spot. I’d have to do without him. I’d send him naked photos of myself in Photoshop-ready positions. He could use his graphic design skills to copy-and-paste himself in there next to me, behind me, whatever. We could have evidence of our congress even if we couldn’t have the congress itself. But C wouldn’t bother with the photos: his desire was a spotlight, shining with impressive intensity and focus, but only on the thing right in front of him. I was barely able to get him to return a text message, even the dirty ones.

I thought of sending him something explicit. Something I’d like to do with him. But in all honesty all I really wanted to do was stay here in bed until everything changed around me. Besides which, it was a challenge for me to compose erotic messages. I always got lost in the parts of speech: if I wanted something involving one particular part of his body, I had trouble not using the preposition “with,” telling him to do something “with” it, or else I would be telling him to “put” it someplace. Both structures made the part eerily passive, something he could pick up and set down and use or not use, like a hammer or a telephone. The same thing happened when he talked about things he would do to a particular part of my body: the body that emerged from his description seemed to have only three or four parts, linked hazily by what I would assume was more body. Talking about my body in any way took me apart. Afterward I would lie still and try to put myself back together, naming the parts one by one silently, in order, beginning with the small bones of the foot.

Then there was describing the deixis of the thing through prepositions and directionality: inside me was in, up, deep, down, farther, through—contradicting directions that didn’t seem to add up to one whole person operating in space, much less two. I always had to think about the planar orientation of my body—was I vertical or horizontal? “Put it all the way across.”

In watching porn and listening carefully to what the people on-screen were saying as they did the things they were doing, I had come to understand that the only stable point of orientation was the stomach. Even though they never mentioned it explicitly in their porn talk, all the ins and ups and downs and deeps seemed to indicate a line cutting through the vagina, through the uterus, and right into the center of the body, which also happened to be the center of digestion. This center seemed to be where everyone wanted things to go, deeper and deeper to the innermost point, where they could finally rest.

I rolled over in bed and sent C a text message: I’m starving!

Then I rolled onto my back and stared up at the ceiling. I had at least one eye, pointing straight upward. From this perspective it was easy to pretend that all things were in a state of perfect stillness. If something in the world had moved or acted, then its action would have affected something else, which in turn would be compelled to react. Its reaction, an action upon things other than itself, would cause other reactions that would change the states of other things, a domino effect that would eventually topple something in my visual field, which consisted solely of ceiling. As the ceiling remained the same, so must everything else. That, or the ceiling was shifting but my eyes were not, would never be, sharp enough to perceive it.

I got C’s reply after a few minutes. Eat something from the kitchen, it read.

B would be out in the kitchen or just near it, maybe watching for me, maybe waiting to make me do something. I didn’t know how to tell C that I was afraid to leave this room and step out into the other parts of the house. I didn’t know how to say I was afraid of diluting myself if I encountered B in this fuzzy state, where she resembled me more than I did myself. A woman’s body never really belongs to herself. As an infant, my body was my mother’s, a detachable extension of her own, a digestive passage clamped and unclamped from her body. My parents would watch over it, watch over what went in and out of it, and as I grew up I would be expected to carry on their watching by myself. Then there was sex, and a succession of years in which I trawled my body along behind me like a drift net, hoping that I wouldn’t catch anything in it by accident, like a baby or a disease. I had kept myself free of these things only through clumsy accident and luck. At rare and specific moments when my body was truly my own, I never knew what to do with it.

I picked at a patch of loose skin on my foot, a whitish patch lifting up from the substrate. It must have loosened while I was walking. Tugging on it, I felt the skin pull on my foot, but nothing from the patch itself. It was already leaving me. If I could look into my insides and poke at them, see them day after day, have control over their color and texture, maybe then I’d feel close to the pounds and pounds of matter that lived within me, in my blind spot. Until then, the outer layer would be the innermost part of me, the thing that would evacuate me if stolen, the absolute core.

HOURS LATER, MY PHONE BUZZED. It was C. His message read: Did you eat something yet?

The eggy white of the ceiling was growing grayer all the time. Its nullness was more difficult to see, though there was as much of it. Ted Hartwell, Matt Skofield, Dennis Galp. Had they felt like this before they felt like disappearing; had they stared at their walls for hours, hoping for something to change? A span in my stomach registered discomfort: it ached first like an absence, next like a stone. It read as a trembling, a shiver without the cold, and then as a solid, a sluggish setting of the soft squish in my middle. It was hunger, I thought. It changed in quality as it changed in quantity: it seemed hunger was a tiered thing, a mountain rising to a peak, and each new altitude would be different from the last. Even though a portion of myself was interested in this, interested in climbing to the top of this hunger and discovering what it felt like at its end, it was a normal human life that I was living, and that meant continuing to eat, eating with no end in sight. I got up to go quickly to the kitchen and grab something whole and bring it back to my room to eat it there, alone. If I moved quickly and quietly, B might miss me entirely.

In the kitchen I grabbed an orange and a piece of string cheese and two energy bars specially formulated for women to eat; they were full of folic acid and had a round, feminine shape. Then I heard a noise from behind me. It was a small urgency, like the sputter of a motor the size of someone’s pocket, but it was so close. I expected to see B standing there with something aimed at my head, an electric toothbrush, maybe, or a drill. But there was nobody behind me and nothing really except a window with the curtain still hanging before it, and from the curtain the sound of that little motor going and going and stopping and then going and going. I walked toward it, still thinking of that blank space behind the back of my head that I couldn’t see or protect. When I moved the curtain, there was a pause. And then a dragonfly, beating itself against the screen over and over, whirring like a thing made of feathery gears. Musical sounds came from the surface as it struck the screen, buzzing and chiming, close enough to my face that I could see the smooth panels of its body.

The dragonflies I knew lived only for a few weeks out of the summer and were lazy, hanging still in the air four or five feet above anybody’s head before gliding to the next stopping point. This one was desperate, and though it looked sturdy, something so small and living couldn’t be designed to outlast that sort of wear, repetitive and dumb. I put my finger on the screen where it seemed to be aiming and the sounds paused. I heard the breeze rush around in the quiet. Then the small crashes began again, a few inches below my fingertip. It was easier to watch insects trapped indoors, on their way to a frantic death, than it was to watch this one killing itself to get in. There was nothing for it in here. In here it would die. As soon as it was inside, it would understand it had to get out.

Feet shuffled across the kitchen tile. I turned around and it was B standing there with a cup in her hand, the prettiest one we had, made of thick blue glass. Her face was stark without makeup on, full of peaks and valleys. Her eyes had a hungry look.

“Are you ready?” she asked.

“This dragonfly is beating itself against the window,” I said.

She looked at it blankly.

“I think it’s going to die,” I explained.

“Then we should do it in another room, I guess?” she said.

I stood there looking at the window and then at the food in my hands. The orange was sweating condensation from the refrigerator. Oranges “breathe” even after they are picked. Torn from their branch, they continue to take in oxygen and exhale carbon dioxide through their skin like small, hard, naked lungs.

“I don’t feel very well,” I said.

B looked at me and then she sat down. She seemed to collapse slightly as I watched her, her shoulders slouching forward, caving her chest.

“Look,” she said. “I know it’s not going to look perfect. I’m not going to be mad at you if it doesn’t look right or if I don’t look exactly the way you look. I know it’s not easy to do things with my face. I know that I have weird proportions, and a big nose, and a big forehead. It’s irreparable. That’s why I’ve always been so scared of putting makeup on, that I’d do all that work and end up looking like myself, exactly like myself but with things smeared on me. I just want to try it this once and I don’t know how to do it myself. I’ll probably look awful,” she said.

She was rubbing her thumb hard against the side of the cup like someone trying to rub the prints off her own fingertips.

If you were a person, you were supposed to want to be a better person. Better people had a surplus of themselves that they were willing to give away, something they could separate out and detach. In me the portions only separated, pulling apart and waiting there for something to happen. I could see what it was that I could give B, but I couldn’t really give it. In fact, I wanted to keep it for myself, to take it and run. All around me, people were giving feelings and help to one another all the time, as if it were the only thing to do. And I watched these exchanges like a dead thing, a thing sealed off perfectly, a room with no holes in or out.

“You’ll look great,” I said. The light from the living room lamps felt warm and prickly next to me. “You look great,” I said.

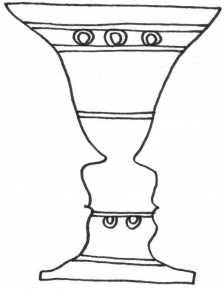

She seemed like she wanted to smile. Her face bunched and crinkled around the eyes. I looked back at the window where the screen sat open to the night air, and I saw nothing, heard nothing.

THE MIRROR IN MY BEDROOM showed the two of us side by side. All I said was that I didn’t want to talk. “I don’t want to get distracted,” I said, and she nodded the way I was sure she would have nodded to anything I said then—worried, but with some potential for happiness hidden within. I did the foundation for her skin, which was the same color as mine. It was a color called bisque, the word for clay in its first stage of firing, hard, dry, unglazed, unfinished. It was also the word for a kind of soup made from the roasted husks of things. The makeup changed the face without changing it at all, it seemed only to restore to it an evenness that it had always held underneath, an even surface without pock or worry. The better person hidden inside the real person.

I wanted to be gone, to be by myself, to be with C, but instead I held still and reminded myself that this impression of uncovering a face was exactly as real as the fact that I was covering up a face at the same time. It was like the optical illusion where you see the vase and the two faces in the same image, but you can’t see them both at once.

The single image splits into two, which occupy the same space without sharing it. Or maybe it’s the opposite: the two objects find themselves in shared space, and the thought of one after the other in the mind of the viewer’s eye, vase face vase face vase face vase face, makes them grow together. The two words even begin to sound alike, like the same words spoken in the mouths of two people from different, distant places. I poured makeup on a white foam sponge so that it looked like a little puddle of skin suspended on nothingness, and then I dabbed it against her cheek over and over again. I dabbed it against her cheek, and then I did smooth, long strokes. I left skin-colored streaks that vanished a little more with every stroke. She was disappearing, or reappearing, or appearing for the first time, whatever.

I had covered all the spots, and now, when I looked at it, her face had the texture of a piece of pottery. I saw pores only when I leaned in close to the nose, where they appeared as tiny skin-colored mounds rising out of little sloping craters. People were such fragile things: they existed only from a certain angle, at a certain scale and spacing. Forget where to stand and you’d lose them completely. From this distance she didn’t resemble me much, though she didn’t exactly resemble herself, either. I rubbed at the edge of her jaw to blend the makeup. Then I did the lips. I used the things I had around, without wiping them off: my own lip balm, gooey and flavored like an orange Creamsicle, a lipstick that I wore a lot and had worn down to a flat, wet-sheened plateau with half a rim on it. I dabbed the color on with my fingertip, the padded part, poking at her lower lip and watching it spring back up. It was just like painting a portrait of myself, I thought, onto the face of another person.

I remembered one summer that I spent at my aunt’s house when I was younger, middle school, maybe. My aunt spent most of her day doing embroidery while her husband was at work, sitting in front of the TV and watching movies on mute. The movies were action films, thrillers, things that she and my uncle had originally bought for their son to watch. She didn’t pay much attention to the story line; the movies were a type of home decor, a device casting light and movement. I would walk through the living room on the way to somewhere else and see the warm yellow glow of an on-screen explosion playing off her smooth, serene face.

One of the movies she put on involved two men who were hardly ever pictured in the same frame. One was squarish and broad, the other angular and hawklike. The squarish man was seen in an office and then in a sort of hospital room. The angular man was pacing around a tarmac. Then the angular man was waking up and walking around. Then the square-jawed man was waking up. They both seemed to chase something, separately, using many different kinds of vehicles—planes, cars, boats. I understood it as some sort of story where two men competed to be the first to capture some unspecified thing they both wanted. Years later, C told me that it was actually a movie about identity theft. One of the men had swapped appearances with the other, then the other swapped appearances with the first. Then they worked to undo each other. C said that I should have picked up on the identity swap by noticing that the square man’s body language was initially heroic and then became sneaky and aggressive, while the angular man’s body language began sneaky and turned heroic. I told him that it would be nice if we could all think that way, but in actual life we were supposed to recognize a person in spite of their mannerisms rather than because of them. We were supposed to trust the similarity of their face in the moment to the face we remembered. “Otherwise,” I said, “I would treat you like a stranger every time your mood changed.” C had just looked at me for a while, seeming confused, not saying anything at all.

I held B’s smallish face in my hands and I gripped her chin a little harder than I had to because I could get away with it, I was making her so happy right now. Before there were mirrors or cameras to allow you to face yourself, you had to see yourself through other people. I tried to think that I was painting a picture of my face on hers so that I could see myself better. See myself filled out rather than flattened, see myself as C saw me. I wasn’t losing anything or giving myself away, I was just expanding, becoming more, many, like the television image and its occupation of all those otherwise empty screens. The image I thought of as mine sitting on the surface of her skin would absorb her to me and I might know what it was like to be myself outside of myself, for once. To see a part of myself that I could observe and recognize, but which transmitted no feelings. A numbed-out limb that could do what it did without me.

I was still hungry, and the tips of my fingers trembled against her skin as I did the thick black line on the eyelid. I hoped that I’d mess it up, but I had no practice doing anything other than trying to make it perfect and the same each time, so it was the same. And as I saw the face take shape, I felt less and less bothered on my own behalf. I felt more like some entirely other person, a casual spectator. There was a flat pleasure in seeing it unfold from this angle, this image that was pleasing to me, so pleasing to me that I had chosen it ten years ago and repeated it upon myself pretty much ever since. As I worked, I tried to find every one of the ways in which our faces differed: the slight cleft in her chin, the widening of her nose at its tip, the mole on her lower lip that looked like a small wart. Now I just sort of let go, and I thought about how different it was to see this image so clearly, familiar and unfamiliar at the same time. It felt like it used to feel to watch myself put on makeup, before it became a thing my hands did almost without me. When I did the dot of silvery stuff at the inner corners, I was done. I turned around to look at us in the mirror.

“It looks so good,” B said, her eyes opening wide.

It did look good. Her eyes looked huge, her mouth smaller and more precise. I had buffed away the dark circles and the random mole. The dark around the eyes distracted from their anxious expression and made her less like prey, more like a predator. She was smiling now, and this changed her face dramatically. It put shadows under her cheekbones and lines around her mouth. She looked like the girls on TV commercials, thrilled at the condition of their outsides.

“You look beautiful,” I said. “You’re a babe.”

I was feeling like I had a surplus, B blinked at me, silent.

“I’m going to go to the bathroom,” she said.

“Okay,” I said.

I didn’t know what she was going to do there, and I didn’t really care. I picked at a loose thread on my comforter to pass the time. I felt light on the inside, like a balloon, and I was incredibly sleepy. When Kandy Kat appears on two television screens at once, does he split in two? Two bodies with two minds pointed out at identical cartoon scenes? Two bodies responding identically, like twin machines? Or is there still one cartoon body, ribby and drained, with a doubled hunger for its double image? I needed some air. I walked to the door and stepped outside. When I looked back, I had a clear view into the bathroom: B had left the door wide open, and even from a distance I could see her standing there in front of the mirror, brushing her fingertips gently against the skin of her nose, cheeks, chin, tracing it with reverence, caressing it like an infant, newly born.

I crossed the lawn in the dark, drawing closer to the house across the street, darkened and uninviting and empty. I looked back behind me, but nobody in the neighborhood was watching, not even B through the skinny kitchen window where she usually stood when I left the house. Nobody was watching me, nobody was thinking about me, I was truly alone. I pushed my way through the unclosed door using my shoulder instead of my hands, arms wrapped around myself like someone with a stomachache or someone who had just been punched in the gut. The door swung slowly back in, shutting out most of the light.

Inside the house across the street it was soundless and clean, free of dust and voices. Everywhere was white with draped cloth, and the moon shone down on the muffled things and gave them an incredibly lonely color. There was a living room to my right filled with hulking white mounds that must once have been a sofa, love seat, armchair, upright piano. To my left was a dining room with three shrouded white chairs and a shrouded white table. From the lumps on its surface, nobody had bothered to clear away dinner before covering it over. I poked at one of the lumps through the pallid sheeting, and it gave way beneath my fingertip with a squish.

There was no family. There was no dog. There weren’t even any insects that had crept in through the open door, the door that released a soft squeal behind me as the wind blew through our street. What had once been a family’s life, still vaguely life shaped, now resembled an arctic scene: white and smooth and cold to the eye. The sofa and love seat vague under sheeting, the obscure shapes of hidden toys. I stood there waiting for something to happen, but nothing was going to happen. It was like watching the body at a wake. My breath slowed and I felt like I might lie down and never get up.

I realized that I was feeling happy.

In the stillness of this dead house, I felt a sudden sense of belonging. It was partial, but still better than nothing. I belonged to this family whom I didn’t know and who didn’t know me either. This family that had left me behind. And though they didn’t know they were missing me, I knew. And that was something. I could still come in here and spend time, conjure them into their domestic spaces, miss them, remember all the things we never did together. I could imagine their voices, imagine finding those voices familiar. I felt as if I knew the entire layout of this house, knew exactly what was under each of these crisp white sheets, even though I didn’t.

Outside, sparse crickets called back and forth. I went into the living room and sat down on the floor behind the ghosted couch. I stared at their white wall and then I lay down on my side. I lay there not thinking about B or C or my job or my parents. I didn’t think about how I looked or how good my skin was today. I didn’t think about food or water or the things that had happened. My breathing slowed. This house with its weird white covers over everything was telling me to do Nothing, and I knew exactly how to do that. I felt like snow, I thought, like snow feels: cold and quiet and close to vanishing. A temporary covering on a small piece of ground. I lay like snow for a long while, as occasionally a car drove past and made the white briefly whiter.

Then I realized that if I stayed here too long, B might try to find me. I stood up and left right away. I closed the front door behind me but left it unlocked.

BACK IN MY BEDROOM, THE television was telling me about a new edible beauty cream. A beautiful woman with black hair is smiling at a midsize jar that she holds in her hands, turning it slightly from right to left as if to admire its label. The woman is already so beautiful that it’s hard to see what she could possibly need inside that jar. Nevertheless she is so excited to open it up, the smile on her face just gets larger and larger as she unscrews the lid, tilts the jar delicately toward her, and then gasps in surprise. A white dove is struggling its way out of the smallish jar, straining its neck against the rim, trying to use its neck and beak as a lever to wrench its downy white breast through the opening. It tries to unfurl a wing, but it’s still too much trapped within the jar, so it looks left and right and then pecks at the parts of the jar that are within its reach. In terms of its experience as an animal, the dove is obviously distressed. Its black beady eyes are still, but its head jerks back and forth, back and forth. As a part of the commercial, however, the dove looks elegant and soft, its feathers fluffy as it twists around, trying to free its wings.

The jar topples over and the dove kind of spills out, taking flight gracefully. As it flies, the voice-over tells us what sorts of things are in TruBeauty’s new interior-exterior skin-perfecting cream. Some of the things are vitamins, antioxidants, moisturizers. The dove is looking great with its wings flapping in slow motion and therefore appearing extra glamorous. When it completes one lap around the room, it circles back toward the beautiful woman, her mouth open in amazement, and it heads straight for her mouth, full throttle. The impact makes a soft thwack sound, and then it’s just the back half of the dove that’s visible sticking out of her mouth and trying hard to wriggle its whole body inside. The voice-over speaks: Most beauty creams stop at the epidermal level, treating only those minor flaws and imperfections that are the easiest to reach. Competing treatments only go skin deep. As it forces itself down her throat, she tilts her chin up gracefully and you can see some muscles at the sides of her neck clenching and releasing, working to help the dove get itself swallowed. When the last claw-tipped foot goes down, she tilts her chin low and smiles radiantly for the camera. Only one beauty cream attacks signs of aging and damage from the inside and out, making sure that threats to your beauty have no place to hide. The beautiful woman dips a spoon into the now dove-free jar of cream and lifts out a creamy mouthful. She dabs a little on her face, and brings the rest of the spoonful to her lips, thrusting it inside luxuriantly. It looks like yogurt, but it’s not. She licks the front and then the back, and then she reclines, closing her eyes and smiling in the sunny glow of her beautiful living room. And the voice-over says: Trust TruBeauty. We know that true beauty begins on the inside.

I curled up on my side and I tried to smile the beautiful woman’s glowing, contented smile. I pretended I felt full and warm and that I had a whole living dove in my belly, looking elegant and soft. The dove was in there, but I wouldn’t hurt it—just hold it, keep it safe inside me. I pretended C was next to me, watching over my body, making certain that nobody could steal my face for as long as he was looking at it. I remembered B’s eye pointed up beneath my gaze, small and immobile and unprotected, with the lid slid all the way back. It was about the size of a thumb, from nail to first joint. My hand twitched. I was digging my two thumbs into the middle of a Kandy Kake, deep into the dark, oily center and pulling it apart. Soon the center would be surface, quivering under air. I could feel myself falling asleep, the sort of sleep you fall backward into, a sleep that feels like water rising higher and higher inside your head until it pushes at the backs of your eyes and the inside of your temples. A Kandy Kake is just like an eye, I thought, and that was the last thing I thought before I was asleep.

In the middle of the night I woke up to a soft hand stroking my hair, but I was hollowed out, exhausted, and I fell back asleep before I could ask who it was.