16

THE BIG AFTERSHOCK: THE EUROPEAN DEBT CRISIS

Beware of Greeks bearing gifts.

—VIRGIL (THE AENEID)

Was it the gift that keeps on taking? What we now know as the European sovereign debt crisis first exploded in Greece in April 2010. It was quite a “gift.” This book concentrates on the United States, but Europe’s debt crisis is arguably the biggest aftershock from the 2007–2009 financial earthquake. Because the economies and markets of Europe and the United States are linked in so many ways, the crisis in the eurozone also appears to be the biggest threat to continued economic recovery here. The story won’t be complete until the “exit” from the European sovereign debt crisis comes. And that may be a long way off.

A serious explanation of the European debt crisis, with all its twists and turns, would require a book in itself, maybe two. And the saga continues. This chapter just scratches the surface, focusing especially on European events that are linked to or parallel to events in the United States.

CRISES HERE AND THERE: SIMILARITIES

The financial crisis in Europe was partly homegrown and partly shipped across the Atlantic from us to them. So it is hardly surprising to find striking similarities.

For openers, both financial crises had their roots in speculative bubbles, most obviously in houses but also in bonds. The real estate craze was particularly pronounced in Ireland, Spain, and the United Kingdom, but it was also visible elsewhere. The financial zaniness we documented in the United States reached tragicomic proportions in Ireland and Iceland, but the UK had a large share, too. Elsewhere in Europe, naïve investors ranging from Belgian widows to German landesbanken (state savings banks), deluded by those tempting AAA ratings, scooped up American mortgage-backed securities with glee, thinking they had struck gold: higher returns without greater risk. In fact, they had struck fools’ gold. All this sounds eerily like America in the bubble years.

The mortgage mess commanded so much attention that hardly anyone seemed to notice the fact that spreads between, say, Greek government bonds and German government bonds—which, remember, are supposed to represent the differential probabilities of default by the two governments—almost disappeared. Could it really be that profligate Greece was no more likely to default than stolid Germany? The proposition was ludicrous, yet market prices came close to saying so. Vanishing risk spreads, as we know, are a hallmark of a bond bubble—whether in the United States or in Europe.

When the housing and bond bubbles burst, recession quickly descended upon Europe, just as it had here. And if homegrown real estate and bond bubbles weren’t enough, virulent infection from the United States after Lehman Day sealed the deal. Virtually every nation in Europe experienced a slump; some were devastatingly long and deep. Greece, Ireland, and Iceland spring to mind as particular horror stories, with the UK and Spain also hit hard. (Spanish unemployment is still over 25 percent.) Even mighty Germany, a stable and conservative country that had no real estate bubble, saw its GDP contract by 6.8 percent between 2008:1 and 2009:1. That’s substantially larger than the 4.7 percent contraction in the United States—and we’re the ones who started the mess.

Recessions blow holes in government budgets, as Americans learned painfully in 2009 and thereafter. Tax collections in European nations dropped sharply as their economies contracted. Similarly, the already-sizable costs of Europe’s social safety net—spending on unemployment benefits, health insurance, public pensions, and the like—rose. Most European governments, turning Keynesian in an emergency, also decided to fight the recession with fiscal stimulus packages of various shapes and sizes. These, of course, also added to their government budget deficits.

And then there were the extraordinary costs of the bank bailouts. In the United States, we created the TARP, which was authorized at about 4.7 percent of GDP but never lent out as much as 3 percent of GDP—and we got it all back with interest. European parliaments enacted myriad mostly ad hoc bailouts on a country-by-country basis, some of them much larger relative to GDP than ours, to prevent their banks from collapsing. And the money didn’t always come back. European attitudes toward bank failures differ sharply from our own. Remember the European central banker who declared after Lehman Day that “we don’t even let dry cleaners fail.”

Finally, in some countries, the government assumed massive amounts of private (mostly bank) debt. These decisions, too, had parallels in the United States, where the federal government guaranteed, assumed, or purchased the debts of companies as diverse as Goldman Sachs, Bear Stearns, AIG, General Motors, General Electric, and so on. But here’s the difference: The net costs in the United States—after interest and repayments—were small, and in most cases negative. In some European countries, they were large.

The poster child is Ireland. By guaranteeing essentially all bank liabilities in September 2008, and subsequently assuming those debts as its own, the Irish government added about 40 points to its debt-to-GDP ratio. In theory, the Irish government was a highly creditworthy borrower that could obtain credit on favorable terms and shoulder the debt burden while Irish banks recovered. In practice, Ireland’s rash actions turned a banking crisis into a sovereign debt crisis. Ireland’s annual government budget deficit in 2010 was a shocking 32 percent of GDP, likely setting a modern-day world record.

CRISES HERE AND THERE: DIFFERENCES

So much for similarities. There are also numerous differences, most of them stemming from the fact that the seventeen countries of the eurozone share a common currency and a common central bank—but not a common government.

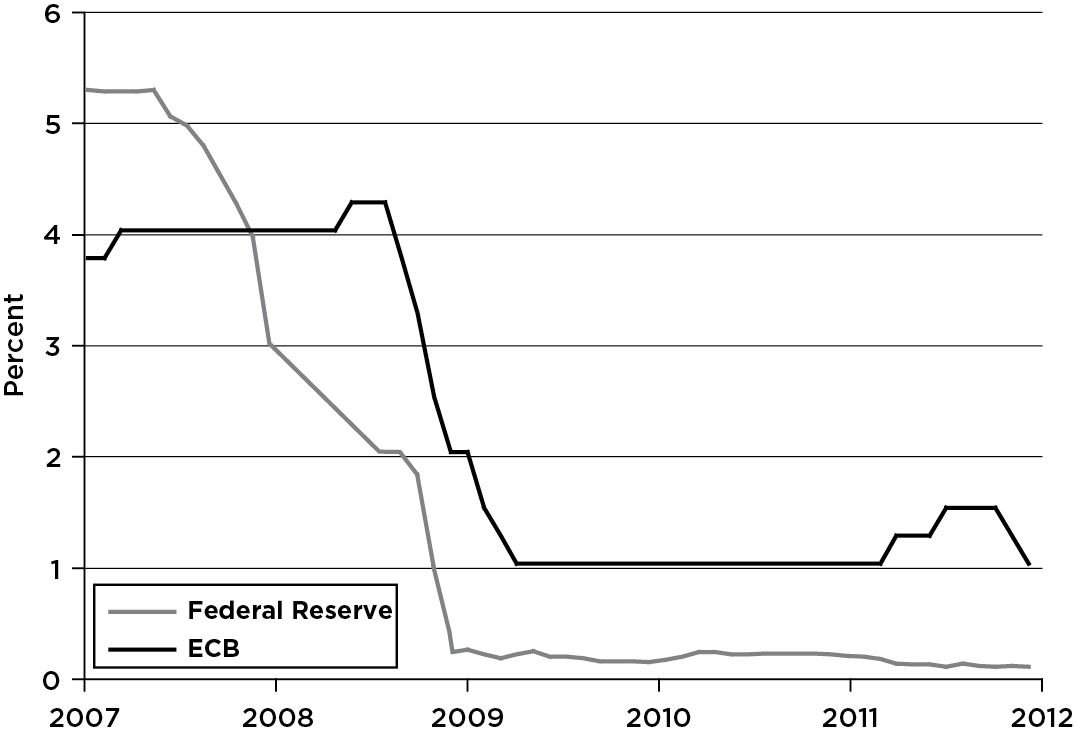

During and after the crisis, the European Central Bank was not nearly as aggressive a recession fighter as the Federal Reserve. The simplest way to see the difference is to glance at figure 16.1, which displays the main policy interest rates of the two central banks: the federal funds rate for the Fed and the ECB’s main refinancing rate. It is evident that the Fed reacted to the burgeoning crisis faster and much more strongly than did the ECB. For example, by December 2008, the Fed’s rate was already down to virtually zero, while the ECB’s was still at 2.5 percent. The ECB even raised rates twice in 2011 (what were they thinking?), while the Fed was looking for new ways to give the U.S. economy a boost. One reason for the difference is that the Fed’s legal mandate instructs it to pursue both low inflation and low unemployment, while the ECB’s legal mandate is only for low inflation.

While the eurozone countries share both a common currency and a common monetary policy, just like the American states, the seventeen countries are far less integrated than the fifty states. It was soon clear that Greece, Portugal, and Ireland were suffering much deeper slumps than, say, Germany, France, and the Netherlands. In principle, the weaker countries needed a looser monetary policy than the stronger ones. In practice, the ECB cannot run separate monetary policies for individual countries; it’s one monetary policy for all.

And also one exchange rate. Because all seventeen countries use the euro, the traditional escape route for a nation mired in a deep slump—a currency depreciation that spurs exports—was ruled out. Which was truly a Greek tragedy. If Greece had its own currency in the summer of 2010, the drachma would have plunged in value, making that sunny Mediterranean land an irresistible destination for vacationers from all over the world. Greece probably would soon have experienced an export boom, led by tourism, and the Greek recession might have ended right there. Instead, the euro kept Greece expensive, and antiausterity riots scared tourists away.

The third critical difference between the United States and Europe is perhaps too obvious to state: They had to deal with Greece; we didn’t. The Greek situation is, if you’ll pardon the Latin, sui generis. Greece has a dismal fiscal history. Economists Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff found that Greece has been in default on its public debt roughly 50 percent of the time since gaining independence in the 1830s! More recently, Greece’s budget deficits were large before the crisis and huge thereafter. The Greeks also turn out to be pretty poor tax collectors—some would say they hardly try. And while the government doesn’t collect taxes very well, it does keep lots of workers on its payroll—people who expect to be paid and to retire young. All part of Athenian democracy, I suppose.

On top of all this, the worldwide recession hit Greece particularly hard. The reasons are not hard to fathom. The Greek economy relies heavily on two export industries: shipping and tourism. In late 2008 and into 2009, world trade suffered a stunning collapse, comparable to that of the Great Depression. There went shipping. And for millions of people all over the world, the recession meant that vacations in Greece were luxuries they could no longer afford. There went tourism.

Between the third quarter of 2008 (the Lehman quarter) and the end of 2010, real GDP in Greece contracted by 10 percent. And it continued to fall. By the end of 2011, Greek GDP was about 16 percent below its 2008:3 peak—and still falling. By comparison, we considered a 4.7 percent decline in GDP devastating. Here’s a scarier comparison: Between 1929 and 1933, real GDP in the United States fell almost 27 percent. We call that the Great Depression. By the end of 2012, Greece was on its way.

And then there was the little matter of lying about its budget deficits and national debt. Greece was admitted to the eurozone in 2001 with a wink and a nod, some fudged numbers, and a public debt well in excess of the Maastricht Treaty’s limit of 60 percent of GDP. But hey, who was counting? In November 2009, just a month after his election, Prime Minister George Papandreou revealed that the previous government had run larger deficits than it had admitted. In an ironic link to America’s financial mischief, it turns out that some financial engineering by Goldman Sachs had helped the Greek government conceal its mounting debt. The news did not amuse Greece’s creditors. The Greek debt-to-GDP ratio, by the way, was already over 120 percent by then—a difficult burden to bear even at modest interest rates. Greek interest rates would soon be immodest.

The United States certainly has badly behaved state and local governments whose fiscal (and other) behavior is roguish or worse. But it is inconceivable that a budgetary disaster in, say, Minnesota—which, proportionately, is to U.S. GDP as Greece is to eurozone GDP—would pull down the entire country. Minnesota would simply, or maybe not so simply, go into default. But starting late in 2009, Greece’s fiscal problems shook faith in many eurozone countries, and even in the euro itself. One for all and all for one, right?

BE WARY OF GREECE

The simplest way to assess a European government’s perceived creditworthiness is to compare its bond rate to that of Germany, then and now Europe’s gold standard. Figure 16.2 displays the spread between the interest rates on Greek and German 10-year government bonds. A few points are evident.

First, the spread was under 1 percent as late as October 2008. In fact, if you look back further, you’ll find even smaller spreads in the years 2001–2007—sometimes under 20 basis points. Prior to the crisis, the Greek government apparently was perceived as being almost as good a credit as the German government. Did someone say “bond-market bubble”?

Second, the spread on Greek debt widened to nearly 3 percentage points during the height of the worldwide financial crisis in early 2009, as investors shunned risk in every way they could. But it fell back down again—though not quite all the way down—when global financial conditions improved later that year. If you were a Greek, you could easily convince yourself that the ups and downs of your government’s bond rate had more to do with worldwide financial developments than with anything happening in Greece.

Then things began to change. Starting late in 2009, Greek interest rates began to move up as investor fears escalated. The Papandreou government reacted by proposing a succession of fiscal austerity programs that were often announced with fanfare, blessed by the European authorities, and then unraveled. It was a portent of things to come. Some of the programs precipitated protests and even riots on the streets of Athens. Greece’s bond rate rose as its credibility sank. Do the math. If your national debt is 150 percent of GDP, and your interest rate is 6 percent, your government must collect 9 percent of GDP just to pay interest. That was about 30 percent of all Greek government revenue. Trouble.

As figure 16.2 shows, things started coming apart around April 2010. Events unfolded quickly: more promises of fiscal austerity; more protests and political turmoil; more downgrades from the rating agencies; more discussions of aid packages from other eurozone countries, and even from the International Monetary Fund (IMF). At one point, Greece’s 10-year bond rate breached 12 percent. The cradle of Western civilization was starting to look like a basket case. At the beginning of May 2010, the first “historic” bailout deal was reached, relieving pressure for a while. But as figure 16.2 shows, the relief was short lived. Try doing the math with a bond rate of 12 percent.

Greece’s difficulties went beyond mere arithmetic, however. Unlike Ireland, which took the painful medicine willingly, Greece was a poor patient with unmanageable politics. A succession of Greek governments had made deals with its citizens that the state could no longer afford. Suddenly, Greeks were asked to pay higher taxes, do without some public services, earn lower wages, and live less well. And why? To placate foreign bondholders? It’s no wonder Greeks protested vehemently and the government failed to deliver on its promises time and time again.

As Greece’s slump deepened, its budget targets grew ever harder to meet. After yet another failed European “summit,” Papandreou resigned in November 2011. His government was replaced by a coalition led by technocrat Lucas Papademos, a well-respected economist who had previously served as governor of the Bank of Greece and as vice president of the ECB. The Papademos government lasted until May 2012, but it then took two elections to install a viable coalition government. Greece has been teetering on the brink ever since.

The political difficulties over the Greek debt situation were by no means confined to Athens. Across the eurozone bargaining table sat not one country but sixteen, and sometimes other EU countries as well, and sometimes the IMF, too. Henry Kissinger once famously asked, “When I need to call Europe, whom do I call?”* When it came to negotiating a Greek bailout, the inability to answer Kissinger’s question posed a serious problem. Who could deliver Europe? Remember, the European Union is a loose confederation of sovereign states, with a minimal central government—more like our Articles of Confederation than the unified nation created by the U.S. Constitution. Remember also that the Articles of Confederation failed. Ironically, one of the major reasons was its inability to deal with government debt.

While lines of authority in Europe are unclear de jure, the Germans and the French normally take the lead de facto. Domestic politics in Germany are particularly intriguing. As Europe’s largest economy, Germany is destined to bear the largest share of any bailout. Yet tax-paying, orderly Germans want to know why they should pay for the failings of undisciplined Greeks who—they believe—work shorter hours, retire earlier, and don’t pay their taxes. It’s a fair question. I often ask Americans to imagine the political reaction here if we were asked to bail out Canada, our friendly neighbor to the north, whose people do work hard, do pay high taxes, and do play by the rules. Yet how many votes in Congress would a Canadian bailout muster? Now change Canada to Mexico and think again—or remember the political donnybrook when our NAFTA partner to the south got in trouble in 1994.

Europe dragged its collective feet, each time kicking the can just far enough down the road to get to the next summit meeting. As they did so, more and more countries were drawn into the muck. Portugal, with its yawning budget deficits and uncompetitive economy, looked too much like Greece for comfort. Ireland, which had experienced a monumental real estate boom and bust, allowed its banks to engage in a surreal array of financial shenanigans, and then bailed them out at colossal public cost, was soon in the crosshairs. Spain, with its whopping real estate bubble and shaky banks, and Italy, with its gigantic public debt and undisciplined government, were next in line. Market participants developed an unflattering name for this list of troubled eurozone countries: the PIIGS (Portugal, Ireland, Italy, Greece, and Spain).

The chances of nipping the crisis in the bud faded away as the list of troubled countries grew. Greece alone was manageable, if it could be quarantined and rescued. After all, while Greek public debt was huge relative to its small economy, it amounted to less than 4 percent of eurozone GDP. Could, say, halving a number like that really pose an insurmountable task for Europe? Not arithmetically. But as Portugal and Ireland joined Greece on the bailout list, the problem grew. And Spain, despite its more reasonable public finances, was bigger than Greece, Portugal, and Ireland combined. Then there was Italy, with the third-largest national debt in the world—trailing only the United States and Japan. Italy turned the old cliché on its head: The country was too big to save.

THE EURO GIVETH, AND THE EURO TAKETH AWAY

The countries in Europe’s so-called periphery benefited enormously from innocence-by-association during the boom years, mainly in the form of lower borrowing rates than they could have achieved on their own. As mentioned, Greek interest rates floated barely above Germany’s.

But once the crisis hit, the euro became a straitjacket. With monetary policy for all seventeen countries made in Frankfurt, the PIIGS could not escape from their slumps with easier money. Nor could they escape with currency depreciation, as there was no longer an escudo, a punt, a lira, a drachma, or a peseta—only the euro. That left only one traditional escape route: spending their way out of the slump with fiscal policy. But as government debt mounted in the periphery, these countries’ ability to borrow started to disappear. For Greece, the door slammed shut. Eurozone membership became a one-way ticket to a deep, long-lasting recession.

It is notable that the UK, which experienced a huge financial meltdown, a sharp recession, and a government budget deficit almost as large, relative to GDP, as Greece’s, fared much better. While it experienced a double-dip recession, there was no British sovereign debt crisis; indeed, British government bond rates are still low. Many economists insist that the main reason is that the UK has its own currency and makes its own monetary policy.

There was also guilt-by-association within the eurozone. As Greece, Ireland, and Portugal crumbled, each requiring a bailout, markets cast a jaundiced eye on Spain and Italy—and interest rates in those countries soared. Even France and Austria lost their cherished AAA credit ratings. Germany, the strongest credit in the eurozone, never worried about rising interest rates—it was the safe haven. But it did worry about a potential breakup of the euro, which would presumably send a new deutsche mark soaring through the roof, thereby killing German exports.

It began to look like the famous old cliché applied to the euro: You can’t live with it, and you can’t live without it.

DON’T BANK ON IT

So far, I have followed common usage by referring to the mess in Europe as the sovereign debt crisis. Investors are worried about the ability of several European governments to pay their bills. But it is also a European banking crisis: Investors are worried about the solvency of many of Europe’s largest banks. Indeed, the two crises are inextricably linked. Part of the governments’ debt problems derive from the expense of bailing out their banks. Europe’s major banks also own a great deal of government debt, on which they can ill afford to take losses. Furthermore, the line between banks and governments is blurrier in Europe than it is here. Don’t forget those too big to fail dry cleaners.

The tight links between European banks and their governments open up new lines of contagion. I have already mentioned that nervous contagion jumped from Greece to Portugal to Ireland to Spain, and so on. That was government-to-government contagion. But another line of contagion also arose in 2010: from Greek government debt to Greek banks (which own a lot of Greek government bonds) and then to banks in other European countries (which have important counterparty relations with Greek banks) and from there to the whole world financial system. The contagion goes the other way, too. In 2012 a European bailout of Spanish banks cast further doubt on Spanish sovereign debt because it initially took the form of new loans to the Spanish government.

When the United States designed and conducted its highly successful bank stress tests in 2009, no one worried that American banks might suffer losses on their holdings of U.S. Treasury securities. But when Europe conducted similar stress tests on its major banks later that same year, the markets were not reassured. One reason was that European banks held lots of European government debt, not all of which looked “good as gold.” But the designers of the European stress tests refused to contemplate the possibility of losses on sovereign debt. Doing so may have been nearly impossible, politically. Which countries would you name? Nonetheless, assuming away sovereign risk looked somewhat surreal in the European context.

Nor was Europe as aggressive as the United States in shoring up the capital positions of its banks. So while market confidence in American banks came back quickly, doubts remained about European banks. These doubts were serious and persistent enough that Christine Lagarde, in her first major speech on becoming head of the IMF, in August 2011, stated bluntly that Europe’s banks “need urgent recapitalization.” She went on: “This is key to cutting the chains of contagion” and should include “using public funds if necessary.” Her stern warning seemed particularly pointed at France, which was remarkable because she had just been France’s finance minister. Furthermore, she was seated right next to her countryman, Jean-Claude Trichet, then the president of the ECB, who had been saying reassuring things about Europe’s banks. Trichet looked less than delighted as Lagarde spoke.

THE RELUCTANT RESCUER

Which brings us to the ECB.

As Europe’s crisis lengthened and deepened, many economists and financial experts concluded that the most plausible way out of the mess was for the ECB to buy massive amounts of government bonds of endangered eurozone countries. Many still feel that way. Why? Because the required amount of money was titanic, and only Europe’s central bank can create euros in unlimited amounts—money that, not incidentally, need not be appropriated by European parliaments. The Federal Reserve, the argument went on, had pointed the way with Bear Stearns, AIG, QE1, QE2, and more. These huge asset purchases, financed by creating as much central bank money as necessary, had saved the U.S. financial system. Surely the ECB—and only the ECB—could do the same thing for Europe.

But the ECB was reluctant to jump into the sovereign debt fray for several reasons. One was the Maastricht Treaty, which had created the ECB in the first place. The Treaty contains the famous “no bailout” clause:

The [European] Union shall not be liable for or assume the commitments of central governments, regional, local or other public authorities, other bodies governed by public law, or public undertakings of any Member State. . . .

Sounds definitive, right? And both the ECB and many European governments have appealed to it repeatedly. Wouldn’t buying up periphery country debt constitute “bailing out” these nations? Perhaps. But what is often forgotten is that the Maastricht Treaty also contains what might be (but is not) called the “bailout clause”:

Where a Member State is in difficulties . . . caused by natural disasters or exceptional occurrences beyond its control, the Council, acting on a proposal from the Commission, may grant . . . Union financial assistance to the Member State concerned.

Do self-inflicted wounds qualify as “exceptional occurrences” beyond a nation’s control? Well, that depends on how creative your lawyers are. Greece, Portugal, Ireland, Spain, and Cyprus all received assistance.

The ECB’s reluctance to intervene was not, however, based exclusively on the no-bailout clause. It has long been considered bad central banking practice to purchase newly issued debt directly from the government. Such monetary financing of government budget deficits is often characterized as “inflationary finance” for a reason. It was, for example, the main route to hyperinflation in places as diverse as Weimar Germany, Latin America in the 1980s, and Zimbabwe recently.

The ECB was consciously built in the image of the Bundesbank and was well aware of this history. It was also acutely aware that the hallmark of a truly independent central bank is its ability to resist government pressures to monetize deficits. With this in mind, the Maastricht Treaty clearly states that:

Overdraft facilities or any other type of credit facility with the European Central Bank or with the central banks of the Member States . . . in favour of Union institutions . . . or public undertakings of Member States shall be prohibited, as shall the purchase directly from them by the European Central Bank or national central banks of debt instruments.

Prohibited. That seems to be a pretty clear ban on central bank financing of budget deficits. And the Germans, for one, took the admonition seriously. But the key word here is directly. After all, every central bank buys and sells government debt in the secondary market as part of its normal business.

The term “inflationary finance” suggests yet another objection to bond purchases, one that both American hawks and Germans remembering Weimar keep reminding us of: Printing money can be inflationary. In the United States, the Fed appealed to its dual mandate to pursue both low inflation and high employment. Bond purchases could be instrumental to the latter. But the ECB was created with only one statutory goal: low inflation. Printing money to purchase government debt is traditionally viewed as an inflationary policy. It would take a pretty slick lawyer to rebrand it as anti-inflationary.

Indeed, as long as Trichet led the ECB, the bank argued that it could never sacrifice its anti-inflation goal to any other cause—not even saving the euro. Quietly, it looked disapprovingly at the Fed’s ever-lengthening list of unconventional monetary policies. Wouldn’t they ultimately prove inflationary? Indeed, it was fear of inflation that presumably motivated the ECB to raise interest rates slightly in 2011, even though Europe was struggling with its debt crisis and weak economic growth.

There was yet another, overtly political reason for the ECB to hold back. Several ECB leaders were quite frank in saying that their reluctance to purchase government bonds stemmed in part from concerns that letting national governments off the hook so easily would ease pressures to get their fiscal houses in order. It was a moral hazard argument, plain and simple: If the ECB started buying Greek, Irish, Portuguese, Spanish, and Italian bonds, that would weaken the incentives of the governments of those countries to solve their budget problems.

In the event, the ECB’s attitude probably helped precipitate changes of government in Greece, Spain, and Italy in 2011. In two of those three cases, technocrats temporarily took the helm of what were supposed to be national unity governments.

SUPER MARIO BROTHERS

One of those technocrats was Mario Monti, an economist by training and sometimes known as “Il Professore,” who was installed as prime minister of Italy on November 16, 2011. By coincidence, that was just fifteen days after another highly regarded Italian economist, Mario Draghi, took over as president of the ECB. Though not related, the pair was quickly dubbed the “Super Mario Brothers.” And they were super. Monti set about trying to reform Italy—not just its budget but even its restrictive labor laws, licensing provisions, and other ingrained anticompetitive practices. Draghi changed the ECB’s course virtually overnight.

It started with interest rates. As mentioned earlier, in an amazing display of obtuseness, the ECB had raised its policy rate from 1 to 1.5 percent in two steps in April and July 2011. With mostly the same members still sitting on its governing council but now under Draghi’s leadership, the ECB reversed those two increases in November and December 2011. Mistake corrected. But that was just the beginning.

Under President Trichet, the ECB had swallowed its objections and began purchasing modest amounts of Greek, Irish, Spanish, Portuguese, and Italian bonds in May 2010. By October 2011, it had accumulated about €170 billion of such bonds, which sounds like a lot but was a pittance compared with what the Fed had done. Critics said bond purchases needed to be expanded greatly. But the ECB countered with the three objections raised earlier: It was not supposed to finance budget deficits; doing so would let profligate governments off the hook; and the inflation-fighting ECB had to conduct offsetting monetary operations to prevent its balance sheet from exploding like the Fed’s. Enter Mario Draghi.

Under President Draghi, the ECB creatively expanded its preexisting Longer-Term Refinancing Operations (LTRO) in entirely new dimensions—both in size and in maturity. Under the new LTRO strategy, which began in December 2011, banks are not only allowed but actually encouraged to borrow large amounts of money from the ECB for terms as long as three years—which is a long way from the typical overnight central bank loan. The three-year maturities, by the way, are far longer than any credit the Fed ever extended. When a bank borrows for three years, it is doing much more than tiding itself over a temporary liquidity problem. Three-year money is a stone’s throw from capital.

At a stroke, the ECB’s new strategy made the European banking crisis far less acute. Banks now had some breathing space. European banks borrowed about €1 trillion from the new LTRO facility in December 2011 and February 2012. That’s real money. And cheap money, too: The banks paid the ECB just 1 percent interest. Thus the ECB was now standing squarely behind its banks, much as the Fed and the Treasury had done with the TARP and the stress tests in 2009.

Think about what the new LTRO meant for Europe’s sovereign debt crisis. The ECB would not buy more sovereign debt for its own portfolio, as its critics had urged. Draghi continued to talk the talk about how bad that would be, and the old bond-buying program receded into the background. But by granting massive amounts of cheap three-year loans to European banks, the ECB was helping private banks do so. And who doubted that European governments would lean on their banks to buy their bonds? (They did—especially in Spain.) While the ECB was not buying bonds directly, it was enabling others to do so on attractive terms. For example, Spanish banks could now borrow from the ECB at 1 percent and turn around and purchase Spanish government bonds paying 5 percent. A pretty good deal.

The new LTRO looked like a game changer. But it did not solve the sovereign debt crisis. The central bank can’t do that, of course, any more than the Fed can solve the U.S. government’s mounting debt problem. Only governments can—by cutting spending and raising more revenue. The ECB’s actions did buy time. But not as much as was hoped. By June 2012, Spanish banks were getting an explicit bailout and pressure was growing for more LTRO.

A month later, the markets were getting jittery again and the euro was sagging. Talk of a euro-area breakup was in the air. Draghi reacted again, this time with words, telling a conference in London that the ECB would “do whatever it takes to preserve the euro,” and “believe me, it will be enough.” It was tough talk, and markets immediately began to speculate that the ECB would soon restart, and probably enhance, its suspended program of buying sovereign debt.

They were right. In early September, Draghi announced a new bond-buying program, called “Outright Monetary Transactions” (OMT), that went well beyond the ECB’s previous efforts. While restricted to bonds with maturities of three years or less, the volume of sovereign debt purchases under OMT is in principle unlimited. So the ECB’s wallet is wide open. To qualify for the program, however, each debtor nation must agree to conditions (e.g., on its budget) set forth by Europe’s bailout fund, the European Stability Mechanism. The ECB will be the financier, but not the judge and jury. Markets cheered the OMT. But at this writing, it is too early to know how it will work in practice. Keep your fingers crossed.

TROJAN HORSES

Then there is Greece, where it all began. Greece differs from the other PIIGs because its fiscal situation looks hopeless—in at least two respects.

First, Greece seems unable to live up to any of its commitments. It pledges budget cuts; it promises to raise tax collections; it commits itself to economic reforms; but it fails to deliver. Part of that failure is a lack of will. The Greeks simply have not been the dutiful patients that, say, the Irish have been. As any doctor will tell you, the cure won’t work unless the patient takes the medicine. And Greek politics are, well . . . Byzantine.

But another reason for failure is beyond Greece’s control. Its paymasters in Europe and at the IMF demand ever more fiscal austerity—higher taxes and less government spending—to shrink the budget deficit. Yes, the deficit must shrink. But such profoundly anti-Keynesian policies have exacerbated Greece’s depression—and it is a depression, not just a recession. That, in turn, makes any budget goal harder to achieve.* Slow-moving Greece is chasing a moving target. In the €130 billion bailout agreed on in February 2012, Greece even had to pledge to reduce its minimum wage by 22 percent. With elections scheduled for May 2012, did anyone really think that would happen? It didn’t. And several fringe parties ran successfully against the €130 billion bailout in the May election, creating the need for a second election in June before Greece got a new government. By August, that government was asking its creditors for yet more delays.

Second, even if Greece somehow manages to achieve the promised deficit reductions, all that effort would not be enough. The interim debt-to-GDP target set for Greece is 120 percent by 2020, and virtually no one believes they will achieve it. But suspend disbelief for a moment and imagine they do. If the average interest rate on Greek government debt then drops back to, say, 5 percent—another barely believable assumption—Greece will still have to raise 6 percent of GDP just to meet its interest payments. That’s a heavy burden. To achieve budgetary stability, Greece must get its debt-to-GDP ratio well below 120 percent. Is that even possible?

On top of all this, Greece has already defaulted on some of its debt. In a lengthy series of negotiations that began in the summer of 2011 and culminated in March 2012, European governments extracted large voluntary concessions from Greece’s private creditors, mainly the banks. Did I say voluntary? Yes, about as voluntary as a deal with Tony Soprano. The final deal imposed more than a 75 percent loss on private bondholders, mainly banks, while sparing official bondholders like the IMF and the ECB. A few bondholders are now suing Greece. And the decision to impose losses on the private sector, but not on the official sector, made some prospective lenders wary of other governments’ bonds—until the ECB promised not to do that in its new bond-buying program.

WHAT’S NEXT?

As this book goes to press, Greece teeters on the brink, struggling—both economically and politically—to live up to its promises. But it has been on the brink for more than two years already. The Greeks apparently know how to teeter. Many economists, including me, wonder why Greece wants to remain in the eurozone in the first place. The price of membership seems excruciatingly high and getting higher. That said, Greek polling continues to show strong support for keeping the euro. Go figure.

By both its words and its deeds, Ireland seems prepared to pay any price—except its status as a corporate tax haven—to remain in the eurozone. Portugal falls somewhere in between, with budget problems like, though not as bad as, Greece’s and a will to stay in the euro that is like, but perhaps not as strong as, Ireland’s. Spain is less secure, though more for its shaky-looking banks than for its public finances, and rather large for a bailout program. As noted, its banks are a heavy weight on the government. And Italy—we hope!—has started down the road to salvation under the leadership of Super Mario Monti. Meanwhile, Europe’s new chief central banker, Super Mario Draghi, seems to be channeling his inner Bernanke.

The Europeans surely live in interesting times. And because of global linkages, so do we. In 2008 a financial panic in the United States quickly infected Europe and the rest of the world. A similar financial panic in Europe in 2013 would quickly infect us, imperiling our still-nascent recovery. That’s the so-called Lehman II scenario. No one wants to go there.