8 PARSING THE NEW ILLEGIBILITY

Earlier, I focused on the enormity of the Internet, the amount of the language it produces, and what impact this has upon writers. In this chapter I’d like to extend that idea and propose that, because of this new environment, a certain type of book is being written that’s not meant to be read as much as it’s meant to be thought about. I’ll give some examples of books that, in their construction, seem to be both mimicking and commenting on our engagement with digital words and, by so doing, propose new strategies for reading—or not reading. The Web functions both as a site for reading and writing: for writers it’s a vast supply text from which to construct literature; readers function in the same way, hacking a path through the morass of information, ultimately working as much at filtering as reading.

The Internet challenges readers not because of the way it is written (mostly normative expository syntax at the top level) but because of its enormous size.1 Just as new reading strategies had to be developed in order to read difficult modernist works of literature, so new reading strategies are emerging on the Web: skimming, data aggregating, RSS feeds, to name a few. Our reading habits seem to be imitating the way machines work by grazing dense texts for keywords. We could even say that, online, we parse text—a binary process of sorting language—more than we read it to comprehend all the information passing before our eyes. And there is an increasing number of texts being written by machines to be read specifically by other machines rather than people, as evidenced by the untold number of spoof pages set up for page views or ad clickthroughs, lexicons of password code cracks, and so forth. While there is still a tremendous amount of human intervention, the future of literature will be increasingly mechanical. Geneticist Susan Blackmore affirms this: “Think of programs that write original poetry or cobble together new student essays, or programs that store information about your shopping preferences and suggest books or clothes you might like next. They may be limited in scope, dependent on human input and send their output to human brains, but they copy, select and recombine the information they handle.”2

The roots of this reading/not reading dichotomy can be found on paper. There have been many books published that challenged the reader not so much by their content but by their scope. Trying to read Gertrude Stein’s The Making of Americans linearly is like trying to read the Web linearly. It’s mostly possible in small doses, dipped in and out of. At nearly one thousand pages, its heft is intimidating, but the biggest deterrent to reading the book is its scope, having begun small as “a history of a family to being a history of everybody the family knew and then it became the history of every kind and of every individual human being,”3 thus rendering it a conceptual work, a beautiful proposal that’s hard to fulfill. “Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try again. Fail again. Fail better.”4 says Beckett, a sentiment that could easily apply to uncreative writing.

The Making of Americans is one in a long line of impossibly scoped projects. The anonymously penned My Secret Life, a twenty-five-hundred-page nonstop Victorian work of pornography is another. No matter how titillating any given page may be—and every single page is—there’s no way of ingesting it straight through. It’s a concept as much as anything, a mad work of language to counter the moral repression of the day both by means of content and sheer bulk. It had to be big: It is surplus text at its most erotic.

Or take Douglas Huebler’s Variable Piece #70 (1971), where he attempts to: “photographically document, to the extent of his capacity, the existence of everyone alive in order to produce the most authentic and inclusive representation of the human species that may be assembled in that manner.”5 Like Stein, Huebler began locally, photographing everyone he passed by on the street. Later, he would go to huge rallies and sporting events, photographing the crowds. Finally, realizing the futility of his efforts, he began rephotographing existing photos of large gatherings of people in order to attempt to accomplish his goal. Of course, he too, “failed better.”

Another instance is Joe Gould’s An Oral History of Our Time, which was purported in June of 1942 to be “approximately nine million two hundred and fifty-five thousand words long, or about a dozen times as long as the Bible,”6 written out in longhand on both sides of the page so illegibly that only Gould could read it:

Gould puts into the Oral History only things he has seen or heard. At least half of it is made up on conversations taken down verbatim or summarized; hence the title. “What people say is history,” Gould says. “What we used to think was history—kings and queens, treaties, inventions, big battles, beheadings, Caesar, Napoleon, Pontius Pilate, Columbus, William Jennings Bryan—is only formal history and largely false. I’ll put down the informal history of the shirt-sleeved multitude—what they had to say about their jobs, love affairs, vittles, sprees, scrapes, and sorrows—or I’ll perish in the attempt.”7

The scope was enormous: included is everything from transcriptions of soliloquies of park bench bums to rhymes transcribed from restroom stalls:

Hundred of thousands of words are devoted to the drunken behavior and sexual adventures of various professional Greenwich Villagers, in the twenties. There are hundreds of reports of ginny Village parties, including gossip about the guests and faithful reports of their arguments on subjects such as reincarnation, birth control, free love, psychoanalysis, Christian Science, Swedenborgianism, vegeterianism, alcoholism, and different political and art isms. “I have fully covered what might be termed the intellectual underworld of my time,” Gould says.8

Gould’s project, too, ended in failure: No manuscript was ever written. It was an enormous hoax, so convincing that it fooled Joseph Mitchell, a reporter for the New Yorker, who wrote a small book about him, ending up being Gould’s de facto biographer.

Although there was no Oral History, there is The Making of Americans. What, then, are we supposed to do with it if not read it? The scholar Ulla Dydo proposes a radical solution: don’t read it at all. She remarked that much of Stein’s work was never meant to be read closely, rather, Strein was deploying visual means of reading. What appeared to be densely unreadable and repetitive was, in fact, designed to be skimmed and to delight the eye, in a visual sense, while holding the book: “These constructions have an astonishing visual result. The limited vocabulary, parallel phrasing, and equivalent sentences create a visual pattern that fills the page.… We read this page until the words no longer cumulatively build meanings but make a visual pattern that does not require understanding, like a decorative wallpaper that we see not as details but only as design.” Here’s an excerpt from the “Mrs. Hersland and the Hersland Children” chapter:

There are then always many millions being made of women who have in them servant girl nature always in them, there are always then there are always being made then many millions who have a little attacking and mostly scared dependent weakness in them, there are always being made then many millions of them who have a scared timid submission in them with a resisting somewhere sometime in them. There are always some then of the many millions of this first kind of them the independent dependent kind of them who never have it in them to have any such attacking in them, there are more of them of the many millions of this first kind of them, who have very little in them of the scared weekness in them, there are some of them who have in them such a weakness as meekness in them, some of them have this in them as gentle pretty young innocence inside them, there are all kinds of mixtures in them then in the many millions of this kind of them in the many kinds of living they have in them.9

This quoted passage proves Dydo’s thesis to be correct. It’s an extremely visual text, with the rhythm being propelled by the roundness of the letter m and the verticality of the architectural letter formation illi of million. The word million is the driving semantic unit, with the visual correlatives—m and on—framing the illi, in an almost palindromatic way, as the on visually glues the two round humps into another m. The negative spaces of the o and n echo the negative spaces of the m. The result is the visual construction of a new word, millim, a gorgeously rhythmic, palindromic unit. The ms lead the eye up a step to the is, which then step you up to the twin ls, the apogee of the unit, and then step back down the way you came. This visual sequence is echoed by the words sometimes and them. The connective tissue is the repeated use of the conjunctions more of them/ little in them/have in them/some of them/kind of them/many of them. which permeate the passage and give it its basic rhythm and flow.

Stein’s words, then, when viewed this way, don’t really function as words normally do. We can read them to be transparent or visual entities or we can read them to be signifiers of language constructed entirely of language. The latter is the approach Craig Dworkin has taken in his book Parse, where he’s parsed an entire grammar book by its own rules, resulting in a 284-page book. The writing is almost an abstraction—a schema—of Stein’s repetitions:

Preparatory Subject third person singular intransitive present tense verb adjective of negation Noun conjunction of alternation Noun locative relative pronoun auxiliary infinitive and incomplete participle used together in a passive verbal phrase definite article Noun genitive preposition relative pronoun period Relative Pronoun third person singular indicative present tense verb and required adverb forming a transitive verbal phrase marks of quotation definite article singular possessive noun verbal noun preposition of the infinitive intransitive infinitive verb comma marks of quotation all taken as a direct object conjunction marks of quotation definite article verbal noun genitive preposition definite article singular noun comma marks of quotation all taken as a direct object conjunction adjective adjective plural direct objective case noun preposition of the infinitive intransitive infinitive verb and passive incomplete participle used as a complex compound passive verbal construction adverb definite article adjective noun period Preposition active participle relative pronoun second person subjective case pronoun modal auxiliary second person transitive verb comma marks of quotation relative pronoun third person third person singular indicative present tense verb and required adverb forming a transitive verbal phrase indefinite article Noun preposition of the infinitive intransitive infinitive verb and passive incomplete participle used as a complex compound passive verbal construction comma abbreviation of an old french imperative period single quotation mark definite article verbal noun genitive preposition definite article noun period single quotation mark marks of quotation10

The source text, Edwin A. Abbott’s How to Parse: An Attempt to Apply the Principles of Scholarship to English Grammar, was first published in 1874 and played a leading role in the pedagogical debate over whether English should be analyzed as if it were Latin. Thousands of copies were printed as textbooks in the last quarter of the nineteenth century. Dworkin says, “When I first came across the book I was reminded of a confession by Gertrude Stein (another product of 1874): ‘I really do not know that anything has ever been more exciting than diagramming sentences.’ And so, of course, I parsed Abbott’s book into its own idiosyncratic system of analysis.” The process was slow, taking over five years to complete. Dworkin called it “EXCRUCIATINGLY slow” when he started, but, by the end, he could sit down with the source text and parse-type at “full speed.”11 But parse-typing at full speed requires little inspiration, tons of perspiration, and an acute knowledge of the rules of grammar. This couldn’t be more different to the famously hypnotic all-night writing sessions of Gertrude Stein, where inspiration was inseparable from process: “When you write a thing it is perfectly clear and then you begin to be doubtful about it, but then you read it again and you lose yourself in it again as when you wrote it.”12 What Dworkin gives us is structure as literature, plain and simple. It’s purposefully lacks the play of rhythmic visuality and orality that Stein worked so hard to achieve. This is not to say that there’s not visual interest in Dworkin’s text, rather it’s asking different questions of us.13

What does it mean “to parse”? The verb to parse comes from the Latin pars, referring to parts of speech. In the vernacular to parse means to understand or comprehend. In literature it’s a method of breaking a sentence down into its component parts of speech, analyzing the form, function, and syntactical relationship of each part to the whole. In computing it means to analyze or separate parts of code so that the computer can process it more efficiently. In computing, parsing is done by a parser, a program that assembles all the bits of code so it can build fluid data structures. But here’s where it gets interesting: computational parsing language was based on the rules of English as set forth by the likes of Abbott. Now, the rules of English are notoriously complicated, idiosyncratic, and ambiguous—just ask anyone trying to learn it—and those vagaries have been carried over into computing. In other words, the compiler can get pretty confused pretty easily. It likes repetition and predictable structures; every ambiguity it must parse will ultimately result in slowing down the program. At his most programmatic, the most logical and least ambiguous part of Dworkin’s book is when he parsed the complete index of Abbott’s book. It’s so simple that even I can parse it. Here’s the index entry for the word colon:

Colon, 309.

which Dworkin parses as:

Noun comma compound arabic numeral period

or the entry for the word “clause”:

Clause, defined, 239.

which is:

Noun comma compound arabic numeral comma Noun period

A column of the index looks like this:

Noun comma compound arabic numeral period

Noun comma compound arabic numeral comma Noun period

Noun comma compound arabic numeral period

Noun comma compound arabic numeral period

Noun comma compound arabic numeral period

Noun comma compound arabic numeral period

Noun comma compound arabic numeral period

Noun comma compound arabic numeral period

Noun comma compound arabic numeral period

Noun comma compound arabic numeral dash compound arabic numeral comma compound arabic numeral comma compound arabic numeral comma compound arabic numeral comma compound arabic numeral period

Noun comma compound arabic numeral period

Noun comma compound arabic numeral period

Noun comma compound arabic numeral comma compound arabic numeral period

Noun comma compound arabic numeral period

Noun comma compound arabic numeral comma compound arabic numeral comma compound arabic numeral period

Noun comma compound arabic numeral period

Noun comma compound arabic numeral period

Noun comma compound arabic numeral comma compound arabic numeral comma compound arabic numeral comma compound arabic numeral period14

This simple and repetitive structure is nearly identical to any number of returns I get when I use the UNIX command ls to view the contents of a directory. Here’s a portion of a log written by a compiler that notes every time a program on my computer crashes:

Kenny-G-MacBook-Air-2:Logs irwinchusid$ cd CrashReporter

Kenny-G-MacBook-Air-2:CrashReporter irwinchusid$ ls

Eudora_2009–07–24–133316_Kenny-G-MacBook-Air-2.crash

Eudora_2009–08–05–133008_Kenny-G-MacBook-Air-2.crash

KDXClient_2009–04–05–030158_Kenny-G-MacBook-Air.crash

Microsoft AU Daemon_2009–04–23–183439_Kenny-G-MacBook-Air.crash

Microsoft AU Daemon_2009–04–23–184134_Kenny-G-MacBook-Air.crash

Microsoft AU Daemon_2009–04–24–030404_Kenny-G-MacBook-Air.crash

Microsoft AU Daemon_2009–04–27–233001_Kenny-G-MacBook-Air.crash

Microsoft AU Daemon_2009–04–27–233203_Kenny-G-MacBook-Air.crash

Microsoft AU Daemon_2009–04–27–233206_Kenny-G-MacBook-Air.crash

Microsoft AU Daemon_2009–04–27–233416_Kenny-G-MacBook-Air.crash

Microsoft AU Daemon_2009–04–27–233425_Kenny-G-MacBook-Air.crash

Microsoft Database Daemon_2009–01–28–141602_irwin-chusids-macbook-air.crash

Microsoft Database Daemon_2009–06–10–103522_Kenny-G-MacBook-Air-2.crash

Microsoft Entourage_2008–06–09–163010_irwin-chusids-macbook-air.crash

Microsoft Entourage_2008–11–11–133150_irwin-chusids-macbook-air.crash

Microsoft Entourage_2008–11–11–133206_irwin-chusids-macbook-air.crash

Microsoft Entourage_2008–11–11–133258_irwin-chusids-macbook-air.crash

Microsoft Entourage_2008–11–11–133316_irwin-chusids-macbook-air.crash

Microsoft Entourage_2008–11–21–131722_irwin-chusids-macbook-air.crash

Note the cleanly consistency of the data structures, subject/date/hard drive/crash, a streamlined way of writing that spans more than a century from Abbott to Dworkin to my MacBook Air—rhetoric, literature, computing—each employing identical rules and processes. When it comes to language, there’s been a general leveling of labor, with everyone—and each machine—essentially performing the same tasks. Digital theorist Matthew Fuller sums it up best when he says, “The work of literary writing and the task of data-entry share the same conceptual and performative environment, as do the journalist and the HTML coder.”15

Dworkin’s index alone goes on for nearly ten pages and is reminiscent of the index of Louis Zukofsky’s life poem, A. He calls the index, “Index of Names and Objects,” but, unlike a typical index that includes nouns or concepts, Zukofsky also indexes a few articles of speech. Here are the index entries for a and the:

a, 1, 103, 130, 131, 138, 161, 168, 173–175, 177, 185, 186, 196, 199, 203, 212, 226–228, 232, 234, 235, 239, 241, 243, 245–248, 260, 270, 281, 282, 288, 291, 296, 297, 299, 302, 323, 327, 328, 351, 353, 377, 380382, 385, 391–394, 397, 402, 404–407, 416, 418, 426, 433, 434, 435, 436, 438, 448, 457, 461, 463, 465, 470, 473, 474, 477–481, 491, 493–497, 499, 500, 505, 507, 508–511, 536–539, 560–56316

the, 175, 179, 181, 182, 184, 187, 191193, 196, 199, 202, 203, 205, 206, 208, 211, 215, 217, 221, 224–226, 228, 231, 232, 234, 238, 239, 241, 243, 245–248, 260, 270, 285, 288, 290, 291, 296, 297, 302, 316, 321–324, 327, 328, 336, 338, 342, 368, 375, 379, 380, 383–387, 390–397, 402, 404, 406, 407, 412, 416, 426–428, 434–436, 440, 441, 463, 465, 468, 470, 473, 474, 476–479, 494, 496, 497, 499, 506–511, 536–539, 560–56317

Yet there are major flaws in Zukofsky’s index. a appears hundreds of times between the pages of 1 and 103, yet they’re not indexed. Same thing with the, which appears on almost every page of the book, yet the index states that the word doesn’t make an appearance until page 175! It turns out that when the University of California Press approached Zukofsky wanting to do a complete volume of A, his initial idea was to do an index only containing a, an and the, words he felt were key to understanding to his life’s work (a subjective constraint-based way of writing). He was delighted with the idea of a conceptual index, and his wife Celia set to work, amassing thousands of index cards, many of which Zukofsky would eliminate when he thought they were unnecessary for his own idiosyncratic reasons—hence the gaps. Clearly Zukofsky thought of the index as another poem—a conceptual one at that—one ridiculing the idea that an artificially formal device such an index could ever truly control, categorize, domesticate, and stabilize such a wild and uncontrollable beast as language, particularly poetic language.

I’ve found that the way to deal with the most perplexing of texts is not to try to figure out what they are but instead to ask what they’re not. If we say, for example, that Parse is not a book of poetry, it is not a narrative, it is not a work of fiction, it is not melodic, it has no pathos, it has no emotion, yet it’s not a phone book, nor is it a reference book, and so on, it gradually begins to dawn on us that this is a material investigation of a philosophical inquiry, a concept in the guise of literature. We then begin to ask questions: What does it mean to parse a grammar book by its own rules? What does this tell us about language and the way we process it, its codes, its hierarchies, its complexities, its consistencies? Who made these rules? How flexible are they? Why are they not more flexible? How would this book be different if it were based on a book about how to parse, say, Chinese sentences? Is Dworkin exacting a schoolboy’s revenge on Abbott by turning the tables on him, by taking an obsessive “All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy” approach? Is he turning Abbott inside out? Or is Dworkin echoing Abbott’s call in Flatland to go beyond the page, giving us a portal through which we may truly see the dimensionality of language? As curious as the material text is, it’s when don’t read it that we really begin to understand it.

But, just when we think we’ve figured it out, we get fooled again. In the midst of all this parsing, you stumble across a sentence in full, normal syntax. This is the entire text on page 217:

——————

NOUN CARDINAL ROMAN

NUMERAL PERIOD

SUBJUNCTIVE MOOD

The answer is, that we desire here to speak of the fact, not as definite facts, but as possibilities.18

It’s a beautiful and certainly relevant sentence, but why? Dworkin is simply translating into normative English the skeletal examples Abbott used to show how sentences should be parsed.

Dworkin’s sentence as parsed—the way it appears in Abbott’s book—is:

Definite article noun singular present continuous verb of definition comma preparatory pronoun first person plural subjective case pronoun first person plural present tense transitive verb preposition of the infinitive infinitive verb genitive preposition definite article objective case singular noun comma adverb of counterfact syncategorematic adjective plural noun comma conjunction syncategorematic plural noun period19

So Dworkin did do some “creative” writing: He had to come up with several sentences comprised of groups of original words that would be meaningful and sensible, which also cleverly reflect on the text. While he could have filled those words with anything—about the weather or plumbing or dancing—he chose to use those instances as philosophical insertions, ones that comment on both his own process and on Abbott’s text. Another reads: “with the entire illustrative sentence meant to suggest an intimately impersonal cast of characters in a reductive permutational drama in the mode of Dick and Jane or Beckett.”20 These small exercises gave Dworkin practice for the next version of the book where he plans to write a narrative novel—completely of his own words—using Abbott’s grammatic structure as a template. He’ll follow the book to the letter, dropping in nouns where they’re supposed to go and present tense transitive verbs where they’re supposed to go, until he’s retranslated the entire book according to its own rules, a doubly Herculean task.

While Dworkin could have merely proposed the work—as could Zukofsky or Stein—the realization of it, the fact of it, gives us something upon which to base our philosophical inquiries. Had he merely proposed the work—“Parse a grammar book according to its own rules”—we’d have had no conception of what it would feel like to read it, to hold it, to examine it. We would have been denied the sheer pleasure and curiosity of it, the workmanship and craftsmanship, the precision of his execution, the beauty of its language, and the beauty of its concept. It’s a wonderful and very powerful object.

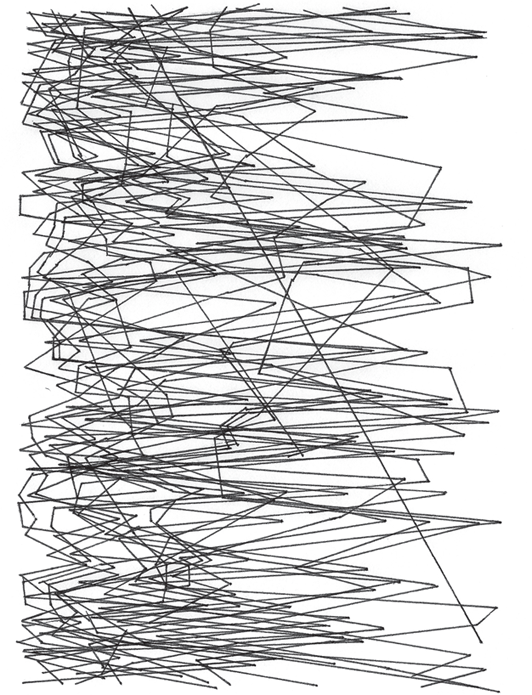

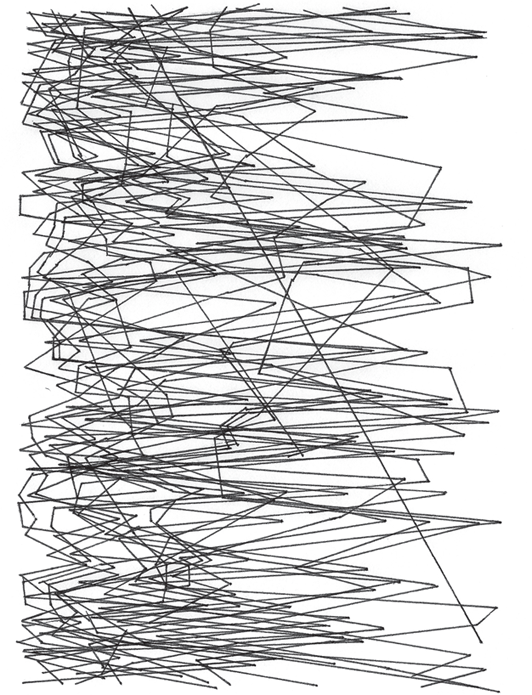

The specter of Edwin A. Abbott haunts uncreative writing. For his 2007 book Flatland, Derek Beaulieu removed all the letters of Abbott’s book of the same title, creating a work of asemic literature, a way of writing without using letters. While based entirely on Flatland, there’s not a word to be found: page after page reveals a series of tangled lines. Like Dworkin, Beaulieu empties Abbott of content to reveal the skeleton of the work. Abbott’s Flatland, written in 1884, chronicles the adventures of a two-dimensional square who meets a three-dimensional cube, challenging his assumptions and demonstrating his inherent limitations. Abbott wrote the book both as a satire about the rigidity of the Victorian class structure and as a tract that ignited the notion of a fourth dimension in popular imagination.

Beaulieu’s tangles of lines represent every letter’s placement in Abbott’s text, from start to finish. He accomplishes this by taking a ruler and beginning with the first letter on each page, tracing a line to the next occurrence of that letter on the page, then the next and so forth until he reaches the end of the page. He then takes the second letter of the first word on the page and traces that in the same manner. He does this until all letters of the alphabet are accounted for.

The result is a unique graphic rendering of each page. No two pages in Beaulieu’s book are identical, and each page contains words and letters in unique sequences. It’s a translation or a write-through in the Cagean tradition, based upon letteristic occurrence instead of semantic content, almost performing a conceptual statistical analysis on the text. Colder and more clinical than Dworkin, and minus the sensuality of Stein, what we’re left with is a completely unreadable work, yet one based entirely on language.

Perhaps the most unreadable text of all is Christian Bök’s Xenotext Experiment, which involves infusing an bacterium with an encrypted poem, illegible to the human eye, but meant to be read far into the future, most likely by an alien race after human beings have long since perished. Bök’s far-fetched works, with its scope of six million years, makes the propositions of Stein, Gould, or Huebler almost seem humble and earthbound by comparison.

Christian Bök’s earlier project, Eunoia, which took seven years to write, consists of five chapters, each one of which uses only one vowel to tell a story, with every chapter containing a variety of linguistic constraints and subnarratives of feasts, orgies, journeys, and so forth. To accomplish such a staggering feat, he read through Webster’s Third New International Dictionary—a three-volume tome that contains about a million and a half entries—doing so five times, once for each of the vowels. When Bök describes his writing process, he sounds like a computational parser, making the idiosyncrasies of the English language speak for themselves, leaving himself with the work that the computer can’t do. “I proceeded then to sort them into parts of speech (nouns, verbs, adjectives, etc.), and then I sorted each of those parts of speech into topical categories (food, animals, professions, etc.) in order to determine what it might be possible to recount using this very fixed lexicon. It was a very difficult task to abide by these rules, but in the end I demonstrated, I think, that it was possible to write something beautiful and interesting even under such conditions of extreme duress.”21

Figure 8.1 Derek Beaulieu, from Flatland.

While the book is immensely pleasurable to engage with, it’s a difficult read because, in spite of all its musical and narrative qualities, what is foregrounded is the structure of the constraint itself, which quickly gets so thick and intrusive that whacking it back to uncover the tale beneath is nearly impossible. Instead of being able to enjoy the text, the reader is drawn into the quicksand of the physicality of language. Readers also continually confront the labor that it must have taken to construct this monumental work, so that the question How did he do this? becomes more pressing than trying to make sense of what the author is saying.

The constraints inevitably force the words into some very stiff prose: “Folks who do not follow God’s norms word for word woo God’s scorn, for God frowns on fools who do not conform to orthodox protocol. Whoso honors no cross of dolors nor crown of thorn doth go on, forsooth, to sow worlds of sorrow. Lo!”22 But the style couldn’t be otherwise if Bök was to abide by the constraint and make it an accountable and realized work of literature.

Far from the drudgery of alienated labor, Bök’s lengthy engagement afforded him—and by extension the reader—an intimacy with language that otherwise couldn’t be gleaned if he had merely proposed the work: “I discovered that each of the five vowels seems to have its own idiosyncratic personality. A and E, for example, seem to be very elegiac and courtly by comparison to the letters O and U, which are very jocular and obscene. It seems to me that the emotional connotations of words may be contingent upon these vowel distributions, which somehow govern our emotional response to words themselves.”23 In order to explore his idea thoroughly, he kept arbitrary decisions to a minimum, an oblique strategy that paid off and helped him—and once again, by extension, the reader—discover the richness of language just as much as a conventionally expressive “creative” work could. He says, “The project also underlined the versatility of language itself, showing that despite any set of constraints upon it, despite censorship, for example, language can always find a way to prevail against these obstacles. Language really is a living thing with a robust vitality. Language is like a weed that cannot only endure but also thrive under all kinds of difficult conditions.”24 What emerges, then, is not arid nihilism or negativity, but the reverse: by not expressing himself, he’s cleared the way to let the language fully express itself.

The Xenotext Experiment involves infusing a bacterium with a poem that will last so long it will outlive the eventual destruction of the Earth itself. While it sounds like something out of a science fiction story, it’s for real: Bök has received hundreds of thousands of dollars in funding from the Canadian government, and he’s working with a prominent scientist to make it happen.

He’s found a species of bacterium—the most resilient on the planet—in which to implement his poems, one that can withstand extremes of cold, heat, and radiation, hence capable of surviving a nuclear holocaust. He’s got high aspirations: “I am hoping, in effect, to write a book that would still be on the planet earth when the sun explodes. I guess that this project is a kind of ambitious attempt to think about art, quite literally, as an eternal endeavor.”

The process of writing this one poem is insanely difficult and has already taken up several years of his life. Only using the letters of the genetic nucleotides—A, C, G, T—in DNA, Bök is literally using this alphabetic scheme to compose a poem. But since there’s only four letters available for him to work with, he’s needed to create a set of ciphers that would stand in for more letters. For instance, the triplet of letters AGT might represent the letter B, etc. But it gets more complicated. Bök wants to write the poem in such a way that it will cause a chemical reaction in the DNA strand, which in turn writes another poem. So that the AGT in the new sequence might this time represent the letter X. And on top of all this, Bök insists that both poems make grammatical and semantic sense. He explains the challenges:

It’s tantamount to writing two poems that mutually encipher each other—that are correlated in a very rigorous way … Imagine there are about 8 trillion different ways of enciphering the alphabet so that the letters are mutually encoded. Pick one of those 8 trillion ciphers. Now write a poem that is beautiful, that makes sense, in such a way that if you were to swap out every single letter of that poem and replace it with its counterpart from the mutual cipher, you’d produce a new poem that still remains just as beautiful and that still makes sense. So I’m trying to write two such poems. One of these poems is the one that I implant in the bacterium. The other poem is the one that the organism writes in response.25

It’s fascinating how Bök still uses the word poem; the new poems might well be written on computer chips or, in this case, inscribed upon life itself. By referring to the work as a poem, he keeps the project squarely in the realm of the literary as opposed to the scientific or the world of visual art. Although the project will take various forms—the final realization will include a sample of the organism on a slide and a gallery show with images and models of the genetic sequence as support materials for the poem itself—Bök’s greatest challenge is to write a good poem, one that will speak to civilizations far into the future. And so Bök notches us the trope of unreadability. This poem is not meant to be read by us, and, by so doing, Bök is enacting one of his long-held precepts, that the future of literature will be written by machines for other machines to read or, better yet, parse.