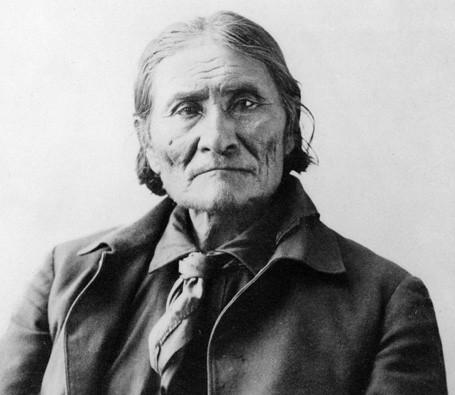

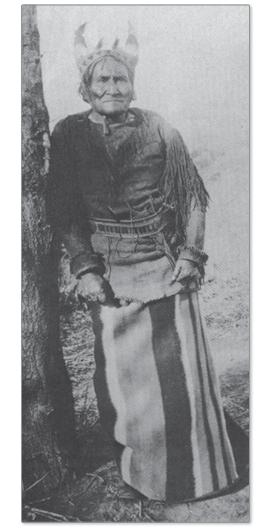

Geronimo 1829-1909

May He Rest in Peace

Back in the late summer of 1989, when the New Haven Advocate’s office was located on Chapel Street, it was not unusual for the odd and the insane to wander in off the streets.

Some came to sell purloined objects. Some came to babble. And some came because the office was open and there was no place else to go.

Most of the time, I was called upon to deal with the crazies, usually in the role of bouncer protecting the mostly female staff. On more than a few occasions, I had to physically remove such visitors.

Often, though, the crazies came looking for me.

Such was the case with the man in olive drab who had a story to tell.

“Hey Altman, someone’s here to see you,” said our receptionist.

Great. When she said it like that, it usually meant another paranoid crack head was coming to call.

I’d been visited by relatives of Jesus, descendents of UFO aliens and a man claiming to be great Caesar’s ghost. The least I could do, I figured, was humor the man and send him, harmlessly, on his way.

I walked out of my office, to the front desk and greeted the man, a short, wiry guy with a craggily, weathered face and stringy hair. Instantly, I sensed there was something about him, something different than the other whackos who walked in off the street.

Extending his hand, he introduced himself.

“I am Geronimo’s great-great grandson,” he said.

“Yeah? And my name is Moses,” I thought to myself.

By the look on the receptionist’s face, I could tell that the man was making her nervous, so contrary to my usual rule, I invited him back to my office.

I sat down and invited him to do the same, but he refused, saying he was more comfortable standing.

As he stood, he began to tell me about his past, which, he claimed, included a stint in the US military, where he served with the special forces. He made it a point to tell me how he’d killed people, though it wasn’t quite clear to me whether the killings took place as a member of the military or on his own.

Either way, I remember feeling just a might uneasy. He might have been hallucinating about being related to Geronimo, but the look in his eyes when he talked about killing people made me think that this guy was telling the truth about something.

After a few minutes more of small talk, I asked him a question.

“So what brings Geronimo’s great-great grandson to New Haven?” I asked, a fairly legitimate question considering the circumstances.

And that’s when he began to tell me an incredible story.

“I am here because my great-great grandfather Geronimo’s bones are here,” he said.

That was fantastic enough. But, the more he talked, the more fantastic the story became.

The bones, he said, were dug up by Prescott Bush, father of George Herbert Walker, the first President Bush. They were taken to the Skull and Bones, a secret society on the Yale campus that counts as members a number of Presidents and other high-ranking government and military officials.

The man, who said his name was Phillip Romero, said he wanted the bones returned to their rightful owner, the Apache. He asked if I would be interested in writing a story.

Well, of course I would be interested in writing a story about the President’s father digging up Geronimo’s bones and bringing them to a secret society in New Haven. There was just one little problem, I told Romero, the man who claimed to be a killer.

Being as tactful as possible, so as not to set him off unnecessarily, I explained that I needed more than his say-so to write a story implicating the father of the President in what amounts to a crime in the state of Connecticut, specifically, the illicit harboring of bones.

The great Apache chief’s self-purported great-great grandson told me that such proof existed, in the form of a picture, which was in the hands of a man named Ned Anderson, a former tribal leader of the San Carlos Apache tribal council.

Anderson, said the man, had been tipped off about Geronimo’s bones by a disgruntled Skull & Bonesman named “Pat,” who told Anderson that Prescott Bush and others dug up the Apache chief’s remains from their burial plot at Fort Sill, Oklahoma, and transported them to the Tomb — the Skull & Bones’ formidable stone headquarters on High Street in New Haven — where they are to this day said to be used in society rituals.

(In addition to becoming a cult figure for his efforts to retrieve Geronimo’s bones, Anderson, according to WaBun-Inini, of the White Earth Anishinabe Ojibwa Nation, would later be credited with helping to found Jesse Jackson’s Rainbow Coalition and coining the phrase “Run, Jesse, Run,” in conjunction with Jackson’s nascent bid for the Presidency.)

His story finished, Romero thanked me for his time, turned around and walked out my office. I never heard from him again.

Anderson, on the other hand, I was in contact with frequently — though reaching him was no easy feat.

He lived on a reservation more than 20 miles from the nearest telephone and our conversations had to be scheduled far in advance so that he could hop a ride.

When we did speak, Anderson told a fascinating story, about how he discovered the whereabouts of Geronimo’s bones after a very public battle with Geronimo’s relatives, over where the great chief should be buried.

Anderson wanted the remains moved to his reservation in San Carlos, Arizona. Geronimo’s family, represented by Wendell Chino, a family member and leader of the Mescalero Apache tribe, wanted the remains to remain where they were, or at least where everyone thought they were, in Fort Sill, where Geronimo died in captivity.

Anderson and Chino were never able to resolve their dispute — Chino calling Anderson’s bid “a publicity stunt to attract tourists.”

But that was not the end of the story.

The publicity, said Anderson, spurred a Bonesman named “Pat” to come forward and, perhaps out of guilt, tell Anderson that Geronimo was not buried in Fort Sill, but was instead on a shelf in the “Tomb.”

The bones, said Anderson, were dug up in 1918 by Prescott Bush — father of the first President Bush and grandfather of the second — along with some cohorts.

In addition to telling Anderson about what happened to Geronimo’s bones, “Pat” — whose real identity Anderson would never reveal despite my pleas, whimpers and other forms of persuasion — provided Anderson with a picture of what Anderson claimed are Geronimo’s bones in New Haven.

Anderson said he took that picture and tried to have his Senator at the time, Mo Udall, intervene. He also said he arranged a meeting with then President George H. W. Bush’s brother Jonathan.

“Bush was taken aback when confronted with the evidence,” Anderson told me. Just how far aback was hard to ascertain when I finally tracked down Bush. He was cordial, but did not want to talk about the meeting.

My research on the subject revealed that, with a lawyer willing to fight the battle, there might have been a case to investigate the corpse conundrum under Connecticut state law, which holds that it is unlawful to keep such remains.

But no one I talked to was willing to represent Anderson and everyone I talked to said no one would.

Armed with Anderson’s evidence, I tried to pay a visit to the Tomb.

I slammed the great knocker, which bounced off the metal door with a tremendous thud. Eventually, someone answered and opened the door ever so slightly.

I introduced myself and told the man why I was there. He refused to talk or even let me in.

Taking a page out of the Obnoxious Salesman’s Handbook, I stuck my foot in the heavy metal door in an effort to continue our conversation. The man slammed the door on my foot in an effort to end it.

Ultimately, his impatience (and pressure on my foot) outlasted my patience and I removed my foot, allowing him to close the door on me and any chance of my getting a comment from a Bonesman.

Although Anderson was unsuccessful in finding anyone to represent him and although I was unable to come to any definitive conclusion about Geronimo’s bones, the story I wrote — “Bones of Contention: Skullduggery at Yale?” — made a bit of a splash. A local TV station covered it and interviewed me and I received a call from an Italian news magazine.

I left the New Haven Advocate in 1991 and the story about Geronimo’s bones became a warm but distant memory until just a few years ago, when I began to read about the controversy in the CIA-Drugs Yahoo group and other places on the Internet, leading me to the conclusion that, no matter what happened, Geronimo’s bones have legs.

* *

*

Geronimo - 1890s