In 1949, Yale Daily News Editor William F. Buckley, Jr., DC ‘50, and my father, Yale English professor Richard B. Sewall, had a memorable exchange at Freshman Commons. They were there to help freshmen of the class of ‘53 make the most of their years at Yale. But they disagreed passionately about the purpose of education. Is it active (Buckley) or contemplative (Sewall)?

Buckley, the big man on campus, urged the freshmen to join, heel, compete and succeed. Yale, he said, is your chance to build the networks that will sustain you throughout life. Sewall, a teacher and scholar, urged the freshmen to read, write, discuss and understand. Yale, he said, is your chance to reflect on life itself. Years later, ‘53 alumnus Jim Thomson summed up the student response: “We all knew Sewall was right, but we wanted to be like Buckley.”

Since 1988, three Yale graduates have led the United States. This Yale succession is historic. Never before have three (or even two) successive U.S. presidents studied at the same university. During its tercentenary year, mother Yale codified this lineage by gathering its presidential progeny, separately, back to Yale. At graduation, President George W. Bush, DC ‘68, jokingly likened himself to the Prodigal Son.

Today, Yale uses its presidential lineage as a beacon to attract students, raise money and extend its global presence. But no one studies it. By falling silent on something historic happening in its own backyard, Yale’s community of scholars risks losing its perspective on history. Equally at risk is America’s political press, given its stunning silence on one university’s four-term (and counting) lock on the White House.

So what’s being overlooked? Under scrutiny, the Yale succession is a key to recent history and a gateway to leadership issues of concern to Yale as a “laboratory for future leaders,” in President Richard Levin’s phrase.

All three Yale presidents owe their White House tenures to the Big Money that has tightened its grip on local, state, and national government since the advent of televised attack ads in the 1960’s. In addition, Big Money’s grip on education and media has helped the Yale presidents advance America’s post-Cold War bid for military and economic empire without ever consulting or informing voters. Finally, it was on the Yale presidents’ watch that Big Money corrupted and inflated corporate and political America until the bubble burst, plunging the world into a recession that economists say could last for years.

No economy, national or global, can stand forever on a corrupt political base. Healthy societies, like healthy families, require trust. The seismic convergence of ethics and economics that toppled Japanese and American markets in 1991 and 2000, respectively, now rattles the entire world. Corruption and terror, widely seen as two unethical sides of the same coin of oil and empire, depress financial markets around the globe.

In America, the Dow Jones average reflects a general loss of faith in institutions fueled by Machiavellian venality in politics and by Enronitis in business. The restoration of integrity — a sea change in America’s civic and commercial life — is the task of a generation. It entails creating a new “balance of public and private interests in the global economy,” writes Jeffrey Garten of Yale’s School of Management. If not apparent now, the need for change will become clear as investor mistrust causes market rally after market rally to fizzle.

Does the United States, in its commitment to freedom and democratic values, have the will to effect change? And does Yale, as a laboratory for future leaders, have the will to lead the way in imagining and implementing change? The unwillingness of Japan’s elite universities to produce a generation of tough-minded reformers helps explain why that former economic superpower, now in its thirteenth year of recession, could be stagnate for years to come. Will America be next?

Significantly, the Ivy League aura that shields the Yale succession from scrutiny is fading. In Secrets of the Tomb, a recent history of Skull and Bones, Yale grad Alexandra Robbins, SY ‘98, shows how four generations of Bonesmen created the Bush dynasty that comprises two thirds of Yale’s presidential troika. Looking ahead to 2004, Robbins describes a possible Bush/Kerry contest as “the first Bones versus Bones presidential race.”

In this pairing, Yale comes off more as a club for oligarchs than as a laboratory for leaders. Three more Yale-trained presidential hopefuls bolster this impression: Vermont Governor Howard Dean, PC ‘71, and Senators Joe Lieberman, MC ‘64, LAW ‘67, and Hillary Clinton, LAW ‘67.

In 1949, Yale, in its wisdom, sent Bonesman Buckley and “barbarian” Sewall to Freshman Commons to encourage the class of ‘53 to pursue success and understanding. Today, Yale’s silence on the Yale succession suggests that Yale, to its peril, may be pursuing success alone. The cure for non-reflection is thoughtful dialogue. The stakes are high. Let the dialogue begin.

***

Richard B. Sewall Professor, Dean and Master at Yale University

Picture taken early 1980s — courtesy the Sewall Family

As you know by now, my father, Richard B. Sewall, taught English at Yale for forty years. In the 1960’s, he was the first Master of Ezra Stiles College. He retired in 1976. In June of last year, ten months before his death last April at age 95, he flew from Boston to Chicago to spend three months with me.

In his last years he suffered from dementia, a close cousin to full-blown Alzheimer’s. He stopped writing letters and reading newspapers. Although he could take phone calls, he no longer made them. Most of the time, he seemed to be withdrawing from the world.

One evening in 1999, while he was still at his beloved country home in Bethany, outside of New Haven, I had phoned him and found him utterly disoriented. “Steve,” he pleaded, “I don’t know where I am. What are all these books doing on the walls?”

He was referring to the bookshelves of the cozy study with the little wood burning fireplace where for twenty years he had worked on his National Book Award-winning biography of Emily Dickenson. He was speaking from the house where he and my mother had enjoyed forty years of idyllic rural life, and where, since her death from pancreatic cancer in 1975, he had been bound and determined to end his days, like the New Englander he was, even at the cost of being apart from his three sons.

In his last years, he pursued a number of quests. One related to Yale. Sometimes after an afternoon nap he would appear in a jacket and tie. Glancing at his watch, he would say he had to be downtown at Yale in an hour to give a lecture. “What about, Dad?’ I once asked. “I don’t know,” he said, with a hint of annoyance in his voice, “Whatever they want me to lecture about.”

Another quest was to reunite with his family of birth. Just before we moved him to safety with my brother Rick’s family near Boston, he would tell us he was waiting to be picked up and driven back to his childhood home in Rye, New York. His home in Bethany, with its splendid prospect of the New Haven reservoir and West Rock in the far distance, was now a mere way station in his search for a destination that always eluded him.

One of the joys of living with very old people is the knowledge that not all of their quests are imaginary. One of my father’s real-life quests was visible in the luminous look of recognition he gave me when we met at O’Hare airport last June. He had reached a destination.

And here he was now, in high spirits, sitting opposite me at the sunlit, glass-top breakfast table at my home in Glenview, sipping from a bowl of chicken noodle soup and munching on a tuna fish sandwich. It was amazing to see him. He had made the flight by himself, without a hitch. And now he was bent over, utterly engrossed in the act of eating. Later that summer, I asked him what keeps him going. “Well,” he said, “I get to eat three good meals a day. And I like being around you guys.”

We hadn’t seen each other in months. And I yearned to talk with him about the book I wanted to write. How would our conversation go? Where would it take us? I had no idea. Yet I knew it would be the latest installment in a running dialogue about Yale, education and, in effect, the modern world that began in 1965 while he was at Ezra Stiles, and where I lived while completing a Masters degree in teaching at Yale.

That was an eventful year for me. I studied Romantic poetry with Harold Bloom, sang with the Original Golden Stars, a New Haven gospel quartet, watched Vietnam War hearings conducted by Senator William Fulbright and his Senate Foreign Relations Committee on the color TV at the Yale Law School dining hall, I also met Allard K. Lowenstein, the Yale-trained lawyer, civil rights activist and future Congressman who then was building the student-based antiwar movement that in 1968 would unseat a sitting president, Lyndon Baines Johnson.

Al Lowenstein was the only visitor who was welcome to Stiles at any hour, day or night. He could wake my parents at midnight and within minutes be munching on a sandwich of his own, enthralling us with tales of political intrigue at the highest levels.

. . . . . . .

The highlight of ‘65-’66 for me, however, was the English class I taught at Troup Junior High School in New Haven to 30 ninth grade boys diagnosed as slow learners. Most of these youngsters were nothing of the sort. They were students in a failed school system and residents of a failing city. By 1990, the City of New Haven, decimated by gangs and drugs, would have the highest per-capita murder rate of any city in America.

On my last day at Troup in 1966, school Principal Frank J. Carr asked me what I would change at Troup if could change just one thing. I said the school needed textbooks that were less than six years old. In response, he told me that while the New Haven Board of Education would spend $400,000 that summer on renovations for the Troup dining room, it would spend only $50,000 that year for textbooks for the entire system, grades 1 through 12.

In those days, fat cat general contractors ran the New Haven Board of Education. It was Big Money at the local level. I wonder who controls that Board today.

My year at Troup opened my eyes to the world. My students had problems, but my students were not the problem. To see if they could write, I assigned on the first day of class a one-page answer to the question, “What happened in English class today?” The paper Joe McVety (not his real name) handed me next day began, “At 9:27, Mr. Sewall walked into room 314 wearing his threadbare jacket.” This kid could write. Another student, David Johns, was brighter than most people I met at Harvard, Yale and U. C. Berkeley.

It was not IQ problems but bad schooling and personal problems that held these students back. Take Dexter Matthews, a young man with a bladder problem but no written permission to leave class. Normally well behaved, Dexter would stand up and glare at me whenever I refused his urgent requests to go to the bathroom.

Well into the school year I asked students to write a story in which they tell me an enormous lie, wild and crazy, In his paper, Joe McVety championed Dexter’s cause with a terrific yarn about how, after a global search, detective Dexter had finally tracked the evil Mr. Sewall down to the men’s room of the Seaview Hotel in Paris, France, and, with a tremendous punch, knocked him clear through the skylight window.

The class howled with delight when I read Joe’s paper aloud. But it still hadn’t dawned on me that maybe Dexter did need to go to the john.

One day near the end of the school year, Dexter, in desperation, pulled a knife on me. Standing wide-eyed at his desk, he looked far more scared than I. The class froze. I told him scornfully to put away the knife, go take a leak, and be back in class in two minutes. He did. Finally I saw that Dexter wasn’t trying to con me. But I can’t say I taught him anything in English that year.

Then there was Anthony Tomasino, whose mom had a fresh-baked chocolate cake waiting for me when I visited her home to find out why her son was acting up in class. When I saw the front door had six locks on it, Mrs. Tomasino said that the sixth one was there because Anthony, a sleepwalker who still slept in his mom’s bed, had learned to unlock the first five in his sleep.

At supper throughout the year, I regaled my parents with stories like these. But I learned less about teaching than I should have. My supervising teacher spent a total of 10 minutes with me during entire school year. Yale had never told me to expect any help from her, so I didn’t. Still, after class most days, I wandered the school, taught as a substitute, or visited classes overseen by battle-scarred souls who had stopped teaching years ago, or never started. I got to know the school.

Although my father never visited my students at Troup, the late Paul Weiss did. Paul was a family friend, a Fellow at Stiles and a legend in the Yale philosophy department. He was also one of Yale’s great teachers. What a day that was. Informed that a Yale professor was coming to class, my students expected John Wayne. But when Paul Weiss entered the room — the gnarliest, most eccentric looking guy you ever saw in your life — they thought they had got Mr. McGoo.

What they had was an incarnation of Socrates. Paul confronted them with Archimedes’ paradox of the race between the hare and the tortoise. The discussion was pretty good. It came down to a contest between Paul and the super-sharp David Johns, who loved to argue, but who had a chip on his shoulder that kept him and Paul from coming to terms.

My most memorable moment at Troup, it turns out, was with my least memorable student. Nothing seemed to stand out about Kenny Brown. But here he was one day, in the passenger seat of my ‘65 green WV, getting a ride to the Dixwell Avenue bus after spending 45 minutes with me in after school detention. Kenny and I were on bad terms that day and neither of us felt like talking. Finally I broke the silence and asked him what he wanted to do when he got out of high school.

“I just want to get a job,” he said in voice I had never heard before. It was low and guttural, like a man’s. Dead serious. And yet despairing. What he yearned for in life, at age 15, was a job. What did I yearn for when I was 15? Stamps, girls and soccer. We talked. From then on, I respected Kenny Brown.

. . . . . . .

At supper that night at the long rustic wooden dining table at Ezra Stiles, I told my parents that schools like Troup had broken the Jeffersonian promise of universal public education. My dad agreed. In the years to come, we came to feel that this promise — this fundamental right and indispensable cornerstone of democracy — survived at the national level mainly, and merely, in the “equal opportunity” and “no child left behind” platitudes of public figures who knew full well that American schools were sending millions of youngsters into the world utterly unprepared to survive in it.

Troup Junior High School brought out the Jonathan Kozoll in both of us. The gap between what Yale offered students and what the City of New Haven offered students was not only wrong, it was all but criminal. And we knew that this gap, if not corrected, would ultimately prove fatal to democracy itself.

Several years after granting me the M.A.T. degree in 1966, Yale summarily terminated its rickety M.A.T. program and replaced it with one that has made improvements in the New Haven schools, and, by example, in schools nationwide.

As the response of a torch-bearing university to the developing crisis in American education, however, my father and I felt this program was a drop in the bucket. The need, as we saw it, was for a Yale School of Education that would rival in size, quality and influence Yale’s schools of law, management and medicine. Let this school train superb teachers and principals, much as Yale trains superb lawyers, businessmen and doctors.

Why is it, we asked ourselves, that great universities like Yale, in the quest to explore and to master every aspect of nature and every corner of the world, were so slow to see the obvious: the critical role of universal public education in sustaining a viable democracy?

To this paradox, we took bittersweet comfort in T. S. Eliot’s celebrated account of the belatedness of all self-knowledge:

We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.

. . . . . . .

At the glass-top table with my father last June, the knowledge that Eliot speaks of, and the day that my father and I had hoped for, seemed farther off than ever. The world had entered the era of Enronitis and the War on Terror.

My father had finished his meal. We had discussed family matters. I fell silent, wondering how I would resume the dialogue that had guided me over the past 35 years. His eyes, sunken and watery, were fixed on me. Age be damned, I told myself, we’re gonna talk, full throttle, just like we always have.

At first I didn’t let on that I wanted to write a book. I didn’t have the nerve. Instead, I gave him the big picture, a sound-bite history of the 1990’s, as if he had just gotten back from the planet Mars. I told him about the end of the cold war, the rise of the global economy, the boom in tech stocks, the bursting of the tech bubble, and the War on Terror triggered by 9/11.

He took it all in. For well over an hour, his eyes would neither wander or nor waiver.

I told him about the three Big Money “leadership issues” noted in the Yale Herald piece: campaign finance, America’s post-Cold War drive toward global empire, and the endemic corruptions exposed by the bursting of the tech bubble. And I mentioned a fourth issue: the CIA’s role in advancing the global drug trade that had corroded the American system of justice and decimated nearly every city in the nation, including New Haven and Chicago, the two cities I knew best.

I showed him my copy of the essential book on this topic, The Politics of Heroin: CIA Complicity in the Global Drug Trade, by Alfred W. McCoy, a Yale Ph.D. who teaches at the University of Wisconsin.

Then I brought it all home with a unifying insight. After several months of research, the idea of a Yale succession of U.S. presidents — Bush/Clinton/Bush and their possible Yale-trained successors — had suddenly dawned on me. Omens of Ivy League oligarchy!

To personalize this point, I placed on the glass-top table copy of the American Heritage Dictionary that he had handed me in 1975. “Read the entry for perquisite,” he had said then, with undisguised pride. I asked him to look at it now. I read the entry to him, including the example of usage that follows the definition: “Politics was the perquisite of the upper classes. (Richard B. Sewall)”

He beamed and grasped my hand warmly. A former student of his, later a harmless drudge of a lexicographer at Random House, had recalled it from class, honored him with the attribution, and sent him the dictionary.

Pondering the “end of all our-exploring” belatedness of my discovery of the Yale succession, it struck me that Yale’s string of White House occupants was itself hidden in plain view, celebrated and promoted by Yale, yet screened from critical analysis by 300 years of Ivy League venerability.

What was screened from analysis ran deeper still. Now I had to talk with my father about the covert Yale.

It will not surprise you to hear that two highly secretive, Yale-related institutions, CIA and Skull and Bones, are the wellsprings of this concept. The origins of Skull and Bones, however, just might. I told my father how William Huntington Russell, valedictorian of the Yale class of 1832, and recently returned from a transformative experience at a university-based secret society in Germany, had founded Skull and Bones with drug money provided by his uncle, Samuel Russell, an entrepreneur whose fleet of speedy Yankee Clippers had made him a fortune by transporting opium from Turkey, India and Burma to Canton and Shanghai in the so-called China Trade of the 19th century.

As his past students never cease telling me, Richard Sewall was among the most patient of men. For this reason, the rare moments of anger I saw in him as a child have stayed with me. One such, a recurrent one, had to do with Skull and Bones. At tea with Yale people in our living room, the mere mention of Bones would prompt him to declare it a “curse on the academic life of the university.”

Having thrown down this gauntlet, he would fall silent, giving others the option of pursuing or dropping it. Sometimes someone would pursue it. That is how I first heard about the huge archive of old term papers, covering much of Yale’s undergraduate course offering, that Bonesmen could touch up and resubmit as their own work. It was institutionalized plagiarism, he felt, and he was furious at Yale’s inability to stop it.

In recent months, in overheated yet by no means unsubstantial online histories of Skull & Bones written by “outlaw historians” like Antony Sutton, Kris Millegan, Webster Tarpley and Anton Chaitkin, I had found weightier reasons to be concerned with Bones. Before sharing a few with my father, I wanted first to see if he could recall his old attacks on Bones. So I asked him.

“Sure I do,” he replied, “but more than that, those guys were trying to run the whole damned university!”

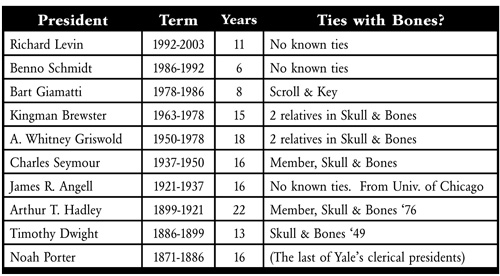

This, to put it mildly, was news to me. Later I would read that Yale presidents have been Bonesmen or related to Bonesmen for 84 of the last 105 years up the time of his retirement in 1976 (See Appendix I)

How, I asked, was Bones trying to run the university? His response, while an answer to a different question, was passionate in its conviction.

“Skull and Bones will never succeed in running the university,” he said. “Yale is too big and too diverse a place to be controlled by any one group.” Suddenly, he was back in the 1950’s, fighting some old battle that I had never heard about and never would. Sensing my interest, he cautioned me: “Watch out. You can never prove anything against those guys. They cover up everything they do.”

For a moment, I had a queasy feeling of tilting at windmills. But anticipating that my father, even at age 95, would want documentation, I had at hand materials photocopied from the U. S. Government Documents Office at Northwestern University. These made reference to several Bonesmen, one of whom was the first of three generations of Bush family members who were Bonesmen.

I showed him four U.S. Treasury Department vesting orders issued in late 1941, after Pearl Harbor, and ordering the confiscation, under the terms of the Trading with the Enemy Act, of the assets of four corporations set up and run by Averell Harriman ’13 and his chief lieutenant, Prescott Bush ‘17, grandfather of the current president, whom, as a child in 1950’s, I remembered as a respected Republican senator from my home state of Connecticut. [See Appendix II, to be put online].

Identified by name on one of these orders were Prescott Bush, and another Bonesman, Roland Harriman ‘17, Averell’s younger brother. Since the early 1920’s, the four Harriman firms had raised millions from American investors not to build up Adolph Hitler’s transportation or agriculture infrastructures, but to build up Hitler’s military machine.

“Dad,” I said, “If you spend a couple day on the Internet, you may get the feeling that the United States is run by a group of Ivy League arms merchants!” In the past, an incendiary assertion like this — and had I made one or two over the years — would have triggered a soothing, quietistic “yes, but” response. But not now.

I paused. We looked at each other. He seemed sad. “Dad, are you sure you want me to go on with all this?” I asked him, laughing as I spoke, “This ain’t fun, and, believe me, it only gets worse!” He smiled affectionately and nodded yes. This was one of our moments. We were on a quest.

. . . . . . .

I showed him Houston Chronicle accounts from the early 1990’s describing long-standing business dealings between the Bush and bin Laden families. These, I said, began in the late 1970’s when Sheik Mohammed bin Laden, the family patriarch and Osama’s father, had, through a friend of the Bush family named James R. Bath, invested $50,000 in Arbusto, the oil exploration company founded by George W. Bush with his father’s help.

I added that on September 11, 2001, Shafiq bin Laden, an estranged half-brother of Osama, had represented his family’s investments at meeting of the Carlyle Group in Washington, D.C. Carlyle is a $16 billion private equity firm that buys up and turns around ailing firms, especially defense contractors. George H. W. Bush serves as a Senior Consultant there. And as Dan Briody establishes in his recent book on the firm, that Fred Malek put George W. Bush on the Caterair Board from 1990-94 while Caterair was owned by Carlyle.

It was important to understand, however, that questionable dealings of American industrialists and politicians were by no means limited to the Bush family or even to the Republicans. Averell Harriman, I told my father, was a career Democrat. I passed on the observation by one of the outlaw historians that Skull & Bones likes to have a voice on both sides of the political debate.

As it happens, Harriman’s third wife, the glorious and glamorous Britisher, Pamela Harriman, had, after his death, presided over the neo-liberal refashioning of the Democratic Party in the 1980’s to the point of advancing the young Bill Clinton to prominence as, of all things, the party’s chief fundraiser.

No arms dealings here, but plenty of Big Money. Clinton was tied to a two-party system — and to a mass media and legal system as well — that had kept knowledge of American business dealings with Hitler and Stalin out of the political mainstream. Only Big Money, it seemed, could account for this act of suppression.

And Big Money had lots to hide. I told my father about two well-received recent books documenting the Nazi business dealings of Henry Ford and James Watson of IBM. In addition, General Motors, the du Ponts and the Rockefellers had all done business with Hitler. Finally, I mentioned Antony Sutton’s controversial three-volume study of the buildup of Stalin’s military machine, even during the Cold War years, by American businesses assisted by the U. S. Department of Commerce. Sutton was a Fellow at Stanford University’s Hoover Institute. His book, as Harvard historian Richard Pipes indicated in endorsing Sutton’s findings, would mark the end of Sutton’s career as a mainstream academic.

Recently I had discussed these dubious dealings with my co-author Bob Back, a financial analyst with a CIA background who, as it happens, had worked during the 1970’s at Brown Brothers, Harriman. “How in hell,” I asked Bob in a moment of anger, “could American industrialists arm the two dictators who had turned the world into a living hell during much of the last half of the 20th century?”

In response, as I told my father, Bob, himself a Bush Republican who sees a need for uninhibited dialogue on these matters, had said, “Big money likes to play both sides of the game.”

. . . . . . .

To wrap things up, I read my father an excerpt from Joseph Trento’s magisterial Secret History of the CIA. This extraordinary book is a history of American intelligence since World War II and, in many respects, of American foreign and domestic affairs as well. James Jesus Angleton ’41, Yale’s second most famous spy (the first being Nathan Hale), is a central figure in this book. Appointed by CIA founder Allen Dulles (a Princeton alum), Angleton was the founding Director of CIA Counterintelligence. His job was to protect the CIA from penetration by Soviet spies.

At Yale, Angleton had majored in English. My father recalled his name and said he had taught him. Angleton was a true aesthete. He created and edited a poetry magazine that he hand-delivered to subscribers at all hours of the night. On a visit to Harvard, he heard a lecture by the English critic William Empson and took it upon himself to bring Empson to lecture at Yale. Not bad for an undergraduate, we agreed.

In 1974, CIA Director William Colby dismissed Angleton for his failed attempt to expose a Soviet mole who, Angleton was convinced, had totally penetrated the CIA. Angleton’s obsessive witch hunt had destroyed the careers of dozens of wrongly accused agents and demoralized the entire agency.

But time confirmed his worst fears. As Trento and David Wise before him have shown, CIA counterintelligence and FBI counterintelligence as well were indeed totally compromised by Soviet agent Igor Orlov, a “man with the soul of a sociopath” yet supremely disciplined and loyal to Stalin. Angleton missed nabbing Orlov by a hairsbreadth. Under scrutiny for years — CIA and FBI agents openly visited Gallery Orlov, the quaint art and picture-framing store that Igor and his wife Eleanore managed in Alexandria, Virginia — Orlov managed to pass two polygraph tests and got away clean.

Angleton, “written off as a crank and a madman by his critics,” and dying of cancer, granted Trento an interview two years before his death in 1987. I read my father the following excerpt:

Within the confines of [Angleton’s] remarkable life were most of America’s secrets. “You know how I got to be in charge of counterintelligence? I agreed not to polygraph or require detailed background checks on Allen Dulles and 60 of his closest friends … They were afraid that their own business dealings with Hitler’s pals would come out. They were too arrogant to believe that the Russians would discover it all. … You know, the CIA got tens of thousands of brave people killed. … We played with lives as if we owned them. We gave false hope. We — I — so misjudged what happened.”

I asked the dying man how it all went so wrong.

With no emotion in his voice, but with his hand trembling, Angleton replied: “Fundamentally, the founding fathers of U.S. intelligence were liars. The better you lied and the more you betrayed, the more likely you would be promoted. These people attracted and promoted each other. Outside of their duplicity, the only thing they had in common was a desire for absolute power. I did things that, in looking back on my life, I regret. But I was part of it and I loved being in it … Allen Dulles, Richard Helms, Carmel Offie, and Frank Wisner were the grand masters. If you were in a room with them you were in a room full of people that you had to believe would deservedly end up in hell.” Angleton slowly sipped his tea and then said, “I guess I will see them there soon.”

I read the last paragraph aloud twice. Then I paused. He was still with me. Shifting gears, I asked; “Who can tell for sure whether Dulles and his pals were liars? But Angleton sure doesn’t sound like a madman.”

I then tried to restore balance by suggesting that the world is a dangerous place, pure and simple. To read academics, journalists and public servants like George Kennan, Arnaud de Borchgrave, William Kristol, Robert Kagan, John Lewis Gaddis or Christopher Hitchens, I said, is to see that people like Allen Dulles and Averell Harriman, and the Yale succession presidents as well, have reason to believe they are addressing dangers that most Americans are too busy or afraid or uninformed to face up to.

The problem is, I told him, that the nation lacks a mechanism — public forums — for distinguishing between dangers real and unreal. Since the advent of network television, I said, civic discourse in America has degenerated to partisan strife. It’s always been this way, the historians tell us, and this backward-looking argument has great force.

Yet America needs to look forward. It has the finest communications technologies ever devised. It should have a public communications system — a civic media — that brings out the best in citizens, not the worst. A problem-solving media, operating year round and prime time at local, state and national levels, that makes citizens and government responsive and accountable to each other.

With this, I had spoken my piece. The sunlight was gone from the dining area. Yet my father’s watery eyes were still on me. He knew all about civic media, a concern of mine over the past 25 years. After a moment, sensing that I was waiting for him to speak, he lowered his eyes.

He had to be tired, I thought, and indeed, at that moment, he looked to be the oldest man I’d seen outside of a wheelchair or a hospital bed. A little puddle of drool flowing from his open mouth had formed on the glass top table beneath his chin. But the slight forward lean in his posture told me that his mind was working.

“So” he said, “What do you want to do with all this?”

“I want to write a book,” I said. “An election year book. One that gives Yale, and the nation as well, a chance to reflect. And to act appropriately. But I need a good title. What do you think should I call it?”

Another moment passed. He leaned forward. “How about Yale and the Modern World?” he asked. It was simple. Yet Olympian in its detachment. I suddenly felt as if, it was I who was returning from Mars - and he who had been here all along.

. . . . . . .

Our dialogue continued throughout that very hot summer. Wearing big old straw hats we took our twice daily walks, measured now not in miles covered, as in days gone by, but in houses passed. We dined alfresco at a Mexican restaurant on Waukegan Road overlooking a parking lot. A little fountain there sent water six feet into the air and brought out the best in children.

At twilight on June 20, my 62nd birthday, four generations of Sewalls – my father and I, my nephew Ethan (‘00), and my four year old son, Joseph Richard Sewall – took to a big open field near our house and threw Frisbees.

During that summer I gave my father baths and backrubs. I played him “Open My Eyes That I May See”, a favorite hymn. This, and songs by Paul Robeson — “Jacob’s Ladder” and “Old Man River” — moved him to tears. And at several memorable gatherings, some of his former Yale students found that Richard Sewall himself could still perform, still make a telling point, even to point of moving others to tears.

. . . . . . .

Table based on Antony Sutton, America’s Secret Establishment, pp. 68-69

* *

*

Author’s Note - Kris Millegan surprised me when he said he wanted to publish this long, rambling piece, originally written as background material for a class at Yale. The piece’s concern with education and civic media does not relate directly to Kris’ concern with Skull & Bones. And while the piece may tie some threads together for readers, it advances little that is new. Instead, it tries to introduce Yale people to aspects of Yale that are seldom discussed in print, yet which have national impact.

Kris wanted to publish the piece verbatim. This impressed me. An “outlaw historian,” as I call him in the piece, was interested in the entirety of something written for academics. All my adult life I have tried to keep one foot in the learning camp of academics and the other in that of non-academics. So has my colleague Bob Back. That’s how we learn, how we get closer to “the nuance,” as Bob likes to call it.

I hope Kris’ book takes us all a step closer to the day when, if we’re able and lucky enough to reach it, outlaw and academic historians alike, and people on the left and right as well, will be astonished to discover how much there is to be learned when we learn from each other.

Steve Sewall, Harvard A.B. ’64, Yale M.A.T ‘66, U. C. Berkeley Ph.D. ’91, is a Chicago area educator and media activist. With Robert W. Back, Trinity College B.A. ’58 and Yale GRD ‘60, he is writing, Yale and the Modern World: Bush/Clinton/Bush, Big Money and the 2004 Presidential Election.