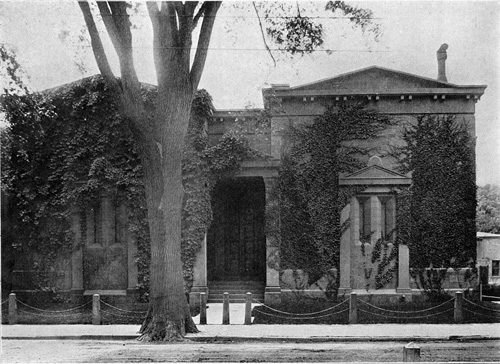

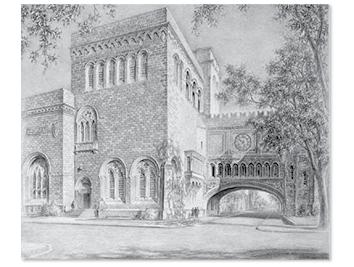

The Tomb, the Temple of the Order of Skull & Bones, 1910

There it sits at 64 High Street, looming large and innocent, a squat funny looking building with slits for windows and big black doors that clang loudly when they shut. The building known as the Temple to members is most often referred to by its very appropriate nickname — the Tomb. You cannot walk completely around the building, and hidden behind the building and its high stonewalls is a secret courtyard.

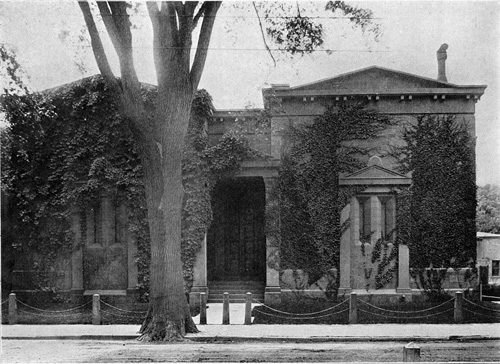

One may actually view the Tomb from a Starbucks on Chapel Street by looking underneath, through the Art Gallery Bridge. Interestingly, there are no tables and chairs in that corner of the cafe, so you may not sit and stare, you may only peek while perusing coffee paraphernalia.

The Art Gallery Bridge

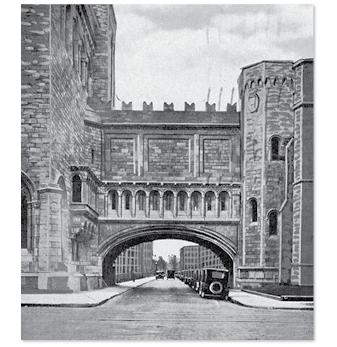

The intersection of High and Chapel Streets is one of the gateways to the Yale campus, a transition point between “Town & Gown.” When the Temple was built in 1856, across the street from the Yale campus, it was pretty much by itself. Then in 1864 through a bequest from Augustus Russell Street the Yale Art School and Gallery or Street Hall was built “specifically at Mr. Street’s direction” on the northeast corner of Chapel & High with one entrance for New Haven citizens and one for the college.

Street Hall’s entrance to the town of New Haven on Chapel Street

Later in the 1920’s the Gallery of Fine Arts, now known as the Old Art Gallery, was built on the northwest corner of High and Chapel Streets and an elaborate gallery bridge walkway was built over High Street connecting the two art buildings. With Weir Hall on one side and later with the modernistic Yale Art Gallery built in 1953, the Tomb was flanked on three sides by Yale art galleries and schools. In the 1920’s there was thought of moving the museum and galleries next to the new Peabody museum on Whitney Avenue, but that was nixed by Street’s original bequest restrictions.

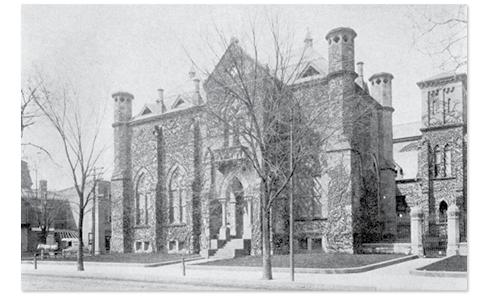

There have always been strong relationships in New England between the art community and secret societies. The Age of Enlightenment, Calvinism, Spiritual Awakenings, The Revolutionary War, Millennialism and other influences had brewed an interesting social stew with the secret societies, primarily Freemasonry and Phi Beta Kappa playing very visible roles. The year Skull & Bones was formed, America’s first college campus art gallery and the first Tomb-like building at Yale, the Trumbull Gallery, was opened on October 25, 1832. John Trumbull, famous early American historical painter, had fallen on hard times and his nephew and Yale’s first science faculty member, Professor Silliman, established the gallery and arranged for him to receive an annuity in exchange for the donation of his paintings to Yale. An early design for the gallery was likened to a traditional Greek Temple. Trumbull designed the building that was finally built. The gallery contained two large windowless rooms and had an eastern entrance flanked by Doric columns and Doric pilasters.

Trumbull Gallery in 1864

Professor Silliman was the founder and editor of the American Journal of Science and Arts. He was a founding member of the National Academy of Sciences and a member of Phi Beta Kappa, which in 1832, in reaction to the Ant-Masonic movement ceased being a secret society and became an open and honorary organization. A reported reaction to the Phi Beta Kappa secrecy change was that Yale students William Huntington Russell and Alphonso Taft asked 13 of their classmates to form with them the Order of Scull & Bones. Phi Beta Kappa did continue also, with Russell, Taft and three other Bonesmen as members.

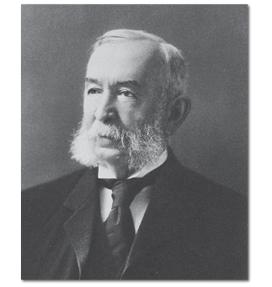

Professor Benjamin Silliman, Jr (S&B 1837)

The school of chemistry, which Professor Silliman founded at Yale in 1847, later developed into the Sheffield Scientific School (SSS) through which Bones was able to take-over Yale. Professor Silliman retired in 1853 to be succeeded by his son, Professor Benjamin Silliman, Jr., a member of a very active group of Bonesmen, the class of 1837. Junior, among other things, discovered in 1855 the process known as cracking, the distillation of paraffin, gasoline and other products from oil. As Professor Silliman, Jr. noted in his report:

Gentlemen, it appears to me that your Company may have in their possession a raw material from which, by a simple and not expensive process, they may manufacture very valuable products.

His findings spurred the first oil rush and brought America’s first oil company, The Pennsylvania Rock Oil Company of New York passed into the hands of New Haven investors, and made fortunes for Townsend and Bissell families, who soon had sons in the Order of Skull & Bones. The thread of the petroleum business continues through the history of Yale, the Tomb and the members of the Order of Skull & Bones.

A drawing of the Tomb from 1860

The Tomb as first built was a nearly windowless two-story mausoleum/Masonic hall style building. It was constructed from brownstone and is generally considered to be the work of local architect Henry Austin, although officially the architect is unknown. There have been no public events held within it, so information about the interior comes from reportage of various break-ins and some people with commercial access. The Order of File & Claw issued a pamphlet in 1876 on a break-in on September 29th of that year. That report is reproduced in full, starting on page 469.

The Tomb — Scribner’s Magazine, April 1876

The most recent reportage about a break-in or “sort of a quick canter through the premises” by some Yale co-eds in the summer of 1979, who were “invited in by a dissident member …” was in an article by Stephen ML Aronson in Fame magazine, Volume 2, Number 2, August 1989:

“There were tons of rooms, a whole chain of them. There were a couple of bedrooms, and there was this monumental dining room with different rolls of Skull and Bones songs suspended from the ceiling. And there was a President Taft memorabilia room filled with flyers, posters, buttons — the whole room was like a Miss Haversham’s shrine. And a big living room with a beautiful rug. And then this big, huge, expensive-looking ivory carving in the hallway. The whole thing was on a very medieval scale. But it was all kind of a shambles. It looked like a boy’s dorm room, like it hadn’t been cleaned up in six months. There were a lot of old bones around — believe me, it could use a women’s touch.

“The most shocking thing — and I say this because I do think it’s sort of important — I mean, President Bush does belong to Skull and Bones, everyone knows that — there is, like a little Nazi shrine inside. One room on the second floor has a bunch of swastikas, kind of an SS macho Nazi iconography. Somebody should ask President Bush about the swastikas in there. I mean, I don’t think he’ll say they’re not there. I think he’ll say, ‘Oh, it wasn’t a big deal, it was just a little room.’ Which I don’t think is true and which I wouldn’t find terribly reassuring anyway. But I don’t think he’d deny it altogether, because it’s true. I mean, I think the Nazi stuff was no more serious than all the bones that were around, but I still find it a little disconcerting.”

Ladies in the Tomb in 1979 — Fame August 1989

Alexandra Robbins in her book, Secrets of the Tomb adds to the public’s knowledge of the interior, although she dismisses the idea that the Tomb may be reached by Yale’s infamous steam tunnels — even when the subject is brought up by New Haven’s finest. There are most definitely extensive tunnel and underground building complexes at Yale. Exploring the steam tunnels is still “among the offenses that are subject to disciplinary action.” The Yale Bulletin & Calendar September 1-8, 1997 Volume 26, Number 2 reports about a $90 million “comprehensive reconstruction” and “modernization” of the power plants and the “interconnecting network of underground pipes and tunnels provide steam for heating, chilled water for air conditioning, electricity and telecommunication systems throughout central campus.” From the relative positions of the power plants and Yale buildings, it is very probable that there is underground access to the Bones clubhouse, as claimed by the New Haven police officers in Ms. Robbins’ book.

Just a little over a block away is the Cross Campus Library, a huge multi-storied underground complex in the central campus core. Next-door just beyond the Tomb’s secret courtyard wall underneath Weir Court is a large underground auditorium.

According to Ms. Robbins there is an underground tunnel going underneath the secret courtyard garden then turning north going only as far as Weir Towers. With the Order’s government intelligence background, I am sure that there could be constructed an entrance into Yale’s hundred-plus year old underground system with a blind alley so that those without the need to know would think that there was only passage to the basement of Weir Towers.

The Tomb was first enlarged in 1883 with the addition of a large dining hall attached at a tee on the rear of the building. The dining hall is two stories with large windows. The additional building doesn’t directly abut the Old Art Gallery building, built later in 1926-27 on the south, but there is a high stonewall between the two buildings that blocks vision and movement.

Bones Hall, Century Magazine — September1888

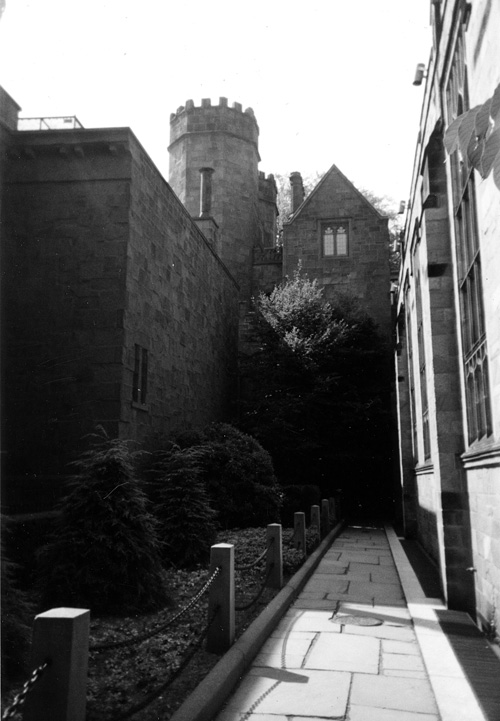

The wall between the Old Art Gallery and the Tomb as viewed looking west from High Street

When the dining room addition was added, George Douglas Miller, a member from 1870, owned the surrounding property and “[h]e raised a great mound of earth and surrounded the property for secrecy.”

The Order writes very little about Mr. Miller. In their catalogues all that is said is that he was an industrialist. George Douglas Miller also gave to the Order one of his private islands, Deer Island, inherited from his father Samuel.

George Douglas Miller, 1847-1932

For some time George lived on the property surrounding the Tomb. His son Samuel was born in 1881 and died in 1883 on the “premises.” According to the Biographical Record of the Class of Seventy, Yale University, 1870-1904, Miller had “prepared” for Yale at Skull & Bones co-founder, William H. Russell’s Collegiate Institute in New Haven. Miller had been in the employ of a New York publishing house, the secretary of the New England Car Spring Company and then he worked with the New York and Straitsville Coal and Iron Company, “a position which came to him through William Walter Phelps (S&B 1860), who had a controlling interest in the company. He was afterwards secretary of the New Haven Electric Light Company”

W W Phelps is a member of the Order who was involved extensively in the Order’s influence on Yale.

George didn’t reminisce about his time in New Haven, his relatives I spoke with knew nothing about his time there and written records are sketchy and sometimes contradictory. As far as I can ascertain, is that George purchased the property all around the Tomb, almost the complete block in the 1870s and early 1880s. There were various buildings both commercial and residential. He then proceeded to raze many of the buildings and built a flat-topped berm around the sides of the Tomb and wanted to build a college such as the Magadelan College at Oxford University. Evarts Tracy (S&B 1890), a member of the NYC architect firm, Tracy & Swartwout began building this college in 1910.

The Tomb, 1906

The exterior of the Tomb that we see today was constructed in 1903. The building was reproduced, the original door was turned into a pair of slit windows and the doorway was put in the middle of the two. The north building is the most recent.

In 1911, Alumni Hall was demolished and it’s two large Gothic stone towers were brought down the street and re-erected at the northwest corner of the new addition to the Tomb. The old Trumbull Gallery was torn down in 1903, after having had windows put in 1868 and then serving as the central administration building until demolished.

Alumni Hall being torn down, 1911

John Trumbull and his wife were buried beneath their gallery in 1843. They were moved to Street Hall for a while to be finally laid to rest across High Street in the basement of the Old Art Gallery, right next to the Tomb. Notably above the bridge between the two art school buildings is a “dimensionally correct (30 feet by 60 feet)” windowless replica of a gallery at the Trumbull Gallery.

The Old Art Gallery and Gallery Bridge

The cloister quadrangle that Miller began was abandoned and in 1912 was purchased by Yale. The building was finally completed in 1924 and was named Weir Hall. It was the home to the School of Architecture for many years. The building was finished using funds from Yale graduate Edward S. Harkness, the son of Stephen Harkness, a Cleveland harness-maker, who was an early investor with John D. Rockefeller and wound up as the second largest shareholder in Standard Oil.

Harkness donated funds again, some sources say in 1924 others say is 1926, but nonetheless, Harkness bought the rest of the Miller property to the south of the Tomb and Yale commissioned Tracy & Swartwout to design the Old Art Gallery. The original design filled up the whole block from High to York Streets and there were designed perpendicular arms connecting to Weir Hall that would have completely enclosed the Tomb. This design was not built with just about half being built. This was just enough to seal off the south side of the Tomb and secret courtyard.

The Secret Courtyard viewed from over the Old Art Gallery

Looking down the small pathway to Weir Hall and the Towers. The northeast corner of the Tomb Library is on the left and the dining hall of Jonathan Edwards College is on the right.

The Secret Courtyard Gate

Looking from Weir Court to the northeast, Weir Hall on left, Weir Towers in middle — note, boarded-up windows. The secret courtyard wall goes from right to center

Southern view from Weir Court toward Kahn’s Yale Art Gallery

There appears to be a vestibule at or a door into Weir Towers from the secret courtyard. Inside the courtyard there is a portico and according to reports there are some memorial benches and a statue of a knight.

A gate entrance to the courtyard is on the northwest corner and a high wall encompasses the courtyard completely on the west side connecting again to the Old Art Gallery.

At certain times of the day you may pass through the locked doors of the antechamber of Weir Hall Towers and into Weir Court. Weir Court, abutting on the west side the Tomb’s secret courtyard 20-foot tall ivy-covered wall, was built on part of the same plateau that Miller had built up. The space is a small and usually private park amid the bustle of the urban campus and probably very similar to the Bones’ secret courtyard on the other side of the wall.

Until 1947, the Department of Architecture was housed in Weir Hall with a view of the secret courtyard, a view they kept when they moved to the top floors of the Louis Kahn designed modernistic completion of the Art Gallery over to York Street. The Tomb was now completely sealed behind the protective façade of the art schools. In 1963 the architecture school moved across York Street but they “still return to Miller’s courtyard every spring for the hopeful rituals of commencement.”

Underneath the Weir Court in 1974-76 there was built, as already mentioned, a large auditorium. This was done without disturbing the large old elm trees. The park-like setting above-ground was restored as it was before the underground structure was built and is natural looking. Personally after visiting the court several times, I didn’t realize that there was an underground structure at the site until reading about it later. It was not evident in casual use and perusal of the area.

After the architecture school moved, Weir Hall became part of Jonathan Edwards College, most of the Weir Hall building becoming the college library. The Towers at this time appeared to have become more part of Bones than Yale, with access curtailed to public and Yalies alike. What the policy is and who owns the Towers are not completely clear.

The Tomb property today is the only private property within the blocks from High to York Streets and Chapel and Grove Streets, the rest belonging to Yale University. From 1911 to 1928 Yale acquired 36 different parcels on the two blocks from Elm to Grove Streets through a series of interesting transactions using “trusts and trusted friends in order to acquire property for itself while vesting legal title in another’s name.” This was done to keep the University’s name off the public records thus not allowing the property owners “to exact a holdout premium.” Yale’s “false front” acting as the Trustee holding the property was “almost exclusively the Union & New Haven Trust Company,” A company with at least three Bones members in the firm, one serving as president for 20 years and Chairman of the Board for 10. Some of these transactions were just simple actions with the trust company holding the property for a few months.

The University’s purchase of the three lots, which gave Yale the entire frontage of High Street from Wall to Grove Streets — where today, stands the Sterling Law School — was a bit more complex.

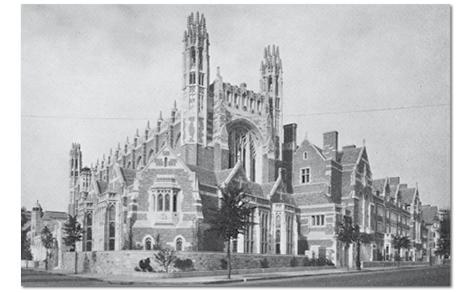

Sterling Law School, Yale University

The University acquired the property in a convoluted four-year scheme with Edward Harkness again supplying oil money for the purchase. The parcel was placed in the name of Bonesman Samuel H Fisher (S&B 1889), a New Haven lawyer, a Yale general counsel, a Fellow of the Yale Corporation and Director of New York Trust among many others. Part of the property deal was the site of the Hopkins Grammar School, a prestigious school of long tradition, which many Bonesmen including founder William Huntington Russell attended.

Hopkin’s Grammar School

The chairman of the Hopkins School, Bonesman Simeon E. Baldwin (1861), facilitated the deal. Baldwin was part of a very powerful Bones Machine in Connecticut and Yale at the time. He served as Governor of Yale 1911-15, after serving from 1907-10 as the Chief Justice of the Connecticut Supreme Court, having been on the court since 1893 — all the time holding a Yale Professorship of Law.

The Hopkins’ property was “held” by Yale University Press, a separate “entity legally distinct from the university,” that was very much under the influence of Bones and friends at Yale. Yale even engineered a little detour in Grove Street to undercut a Mr. Edward Bishop who had brokered for Yale some of the harder to secure residential and commercial properties, when he tried to exact a holdout premium. The land acquisition operation was handled by the office of the Treasurer of Yale, which was held by the Order of Skull & Bones for many years.

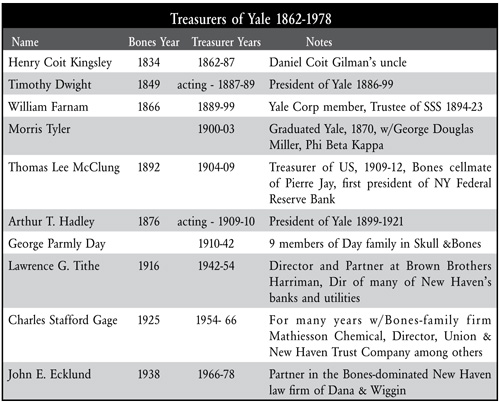

As seen a member of the Order was Treasurer of Yale from 1862 to 1978 except two gentlemen who served for 36 years of that 116 year stretch. The one serving longest, 32 years, hailed from a Bones family.

The manipulation for control had been going on at Yale for many years, From America’s Secret Establishment by Antony Sutton:

Daniel Coit Gilman is the key activist in the revolution of education by The Order. The Gilman family came to the United States from Norfolk, England in 1638. On his mother’s side, the Coit family came from Wales to Salem, Massachusetts before 1638.

Gilman was born in Norwich, Connecticut July 8, 1831, from a family laced with members of The Order and links to Yale College (as it was known at that time). Uncle Henry Coit Kingsley (The Order ‘34) was Treasurer of Yale from 1862 to 1886. James I. Kingsley was Gilman’s uncle and a Professor at Yale. William M. Kingsley, a cousin, was editor of the influential journal New Englander.

On the Coit side of the family, Joshua Coit was a member of The Order in 1853 as well as William Coit in 1887.

Gilman’s brother-in-law, the Reverend Joseph Parrish Thompson (‘38) was in The Order.

Gilman returned from Europe in late 1855 and spent the next 14 years in New Haven, Connecticut — almost entirely in and around Yale, consolidating the power of The Order.

Daniel Coit Gilman

His first task in 1856 was to incorporate Skull & Bones as a legal entity under the name of The Russell Trust. Gilman became Treasurer and William H. Russell, the cofounder, was President. It is notable that there is no mention of The Order, Skull & Bones, The Russell Trust, or any secret society activity in Gilman’s biography, nor in open records. The Order, so far as its members are concerned, is designed to be secret, and apart from one or two inconsequential slips, meaningless unless one has the whole picture. The Order has been remarkably adept at keeping its secret. In other words, The Order fulfills our first requirement for a conspiracy - i.e., IT IS SECRET.

The information on The Order that we are using surfaced by accident. In a way similar to the surfacing of the Illuminati papers in 1783 when a messenger carrying Illuminati papers was killed and the Bavarian police found the documents. All that exists publicly for The Order is the charter of the Russell Trust, and that tells you nothing

On the public record then, Gilman became assistant Librarian at Yale in the fall of 1856 and “in October he was chosen to fill a vacancy on the New Haven Board of Education.” In 1858 he was appointed Librarian at Yale. Then he moved to bigger tasks.

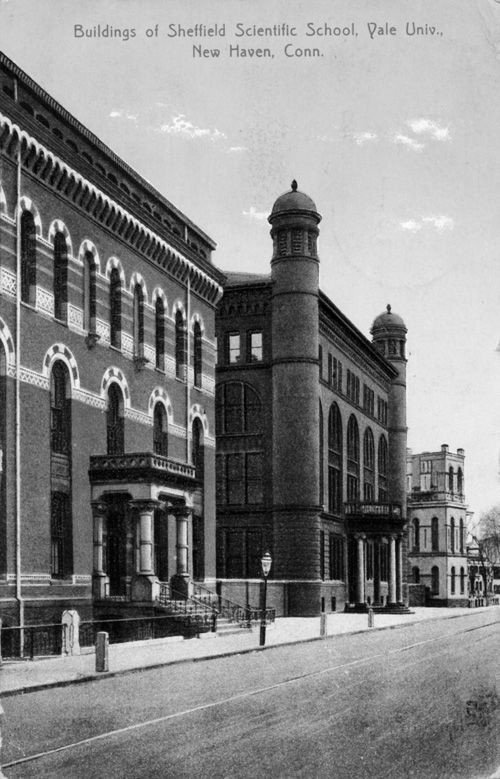

The Sheffield Scientific School

The Sheffield Scientific School, the science departments at Yale, exemplifies the way in which The Order came to control Yale and then the United States.

In the early 1850s, Yale science was insignificant, just two or three very small departments. In 1861 these were concentrated into the Sheffield Scientific School with private funds from Joseph E. Sheffield. Gilman went to work to raise more funds for expansion.

Gilman’s brother had married the daughter of Chemistry Professor Benjamin Silliman (The Order, 1837). This brought Gilman into contact with Professor Dana, also a member of the Silliman family, and this group decided that Gilman should write a report on reorganization of Sheffield. This was done and entitled Proposed Plan for the Complete Reorganization of the School of Science Connected with Yale College.

While this plan was worked out, friends and members of The Order made moves in Washington, D.C., and the Connecticut State Legislature to get state funding for the Sheffield Scientific School. The Morrill Land Bill was introduced into Congress in 1857, passed in 1859, but vetoed by President Buchanan. It was later signed by President Lincoln. This bill, now known as the Land Grant College Act, donated public lands for State colleges of agriculture and sciences … and of course Gilman’s report on just such a college was ready. The legal procedure was for the Federal government to issue land scrip in proportion to a state’s representation, but state legislatures first had to pass legislation accepting the scrip. Not only was Daniel Gilman first on the scene to get Federal land scrip, he was first among all the states and grabbed all of Connecticut’s share for Sheffield Scientific School! Gilman had, of course, tailored his report to fit the amount forthcoming for Connecticut. No other institution in Connecticut received even a whisper until 1893, when Storrs Agricultural College received a land grant.

Of course it helped that a member of The Order, Augustus Brandegee (‘49), was speaker of the Connecticut State Legislature in 1861 when the state bill was moving through, accepting Connecticut’s share for Sheffield. Other members of The Order, like Stephen W. Kellogg (‘46) and William Russell (‘33), were either in the State Legislature or had influence from past service.

The Order repeated the same grab for public funds in New York State. All of New York’s share of the Land Grant College Act went to Cornell University. Andrew Dickson White, a member of our trio, was the key activist in New York and later became first President of Cornell. Daniel Gilman was rewarded by Yale and became Professor of Physical Geography at Sheffield in 1863.

In brief, The Order was able to corner the total state shares for Connecticut and New York, cutting out other scholastic institutions. This is the first example of scores we shall present in this series — how The Order uses public funds for its own objectives.

And this, of course, is the great advantage of Hegel for an elite. The State is absolute. But the State is also a fiction. So if The Order can manipulate the State, it in effect becomes the absolute. A neat game. And like the Hegelian dialectic process we cited in the first volume, The Order has worked it like a charm.

Back to Sheffield Scientific School. The Order now had funds for Sheffield and proceeded to consolidate its control. In February 1871 the School was incorporated and the following became trustees:

Charles J. Sheffield

Prof. G.J. Brush (Gilman’s close friend)

Daniel Coit Gilman (The Order, ‘52)

W.T. Trowbridge

John S. Beach (The Order, ‘39)

William W. Phelps (The Order, ‘60)

Out of six trustees, three were in The Order. In addition, George St. John Sheffield, son of the benefactor, was initiated in 1863, and the first Dean of Sheffield was J.A. Porter, also the first member of Scroll & Key (the supposedly competitive senior society at Yale).

How The Order Came To Control Yale University

From Sheffield Scientific School The Order broadened its horizons.

The Order’s control over all Yale was evident by the 1870s, even under the administration of Noah Porter (1871-1881), who was not a member. In the decades after the 1870s, The Order tightened its grip The Iconoclast (October 13, 1873) summarizes the facts we have presented on control of Yale by The Order, without being fully aware of the details:

They have obtained control of Yale. Its business is performed by them. Money paid to the college must pass into their hands, and be subject to their will. No doubt they are worthy men in themselves, but the many whom they looked down upon while in college, cannot so far forget as to give money freely into their hands. Men in Wall Street complain that the college comes straight to them for help, instead of asking each graduate for his share. The reason is found in a remark made by one of Yale’s and America’s first men: “Few will give but Bones men, and they care far more for their society than they do for the college.” The Woolsey Fund has but a struggling existence, for kindred reasons.

Here, then, appears the true reason for Yale’s poverty. She is controlled by a few men who shut themselves off from others, and assume to be their superiors …

The anonymous writer of Iconoclast blames The Order for the poverty of Yale. But worse was to come. Then-President Noah Porter the last of the clerical Presidents of Yale (1871-1886), and the last without either membership or family connections to The Order.

After 1886 the Yale Presidency became almost a fiefdom for The Order.

From 1886 to 1899, member Timothy Dwight (‘49) was President, followed by another member of The Order, Arthur Twining Hadley (1899 to 1921). Then came James R. Angell (1921-37), not a member of The Order, who came to Yale from the University of Chicago where he worked with Dewey, built the School of Education, and was past President of the American Psychological Association.

From 1937 to 1950 Charles Seymour, a member of The Order, was President followed by Alfred Whitney Griswold from 1950 to 1963 Griswold was not a member, but both the Griswold and Whitney families have members in The Order. For example, Dwight Torrey Griswold (‘08) and William Edward Schenk Griswold (‘99) were in The Order. In 1963 Kingman Brewster took over as President. The Brewster family has had several members in The Order, in law and the ministry rather than education.

We can best conclude this memorandum with a quotation from the anonymous Yale observer:

Whatever want the college suffers, whatever is lacking in her educational course, whatever disgrace lies in her poor buildings, whatever embarrassments have beset her needy students, so far as money could have availed, the weight of blame lies upon the ill-starred society. The pecuniary question is one of the future as well as of the present and past. Year by year the deadly evil is growing. The society was never as obnoxious to the college as it is today, and it is just this ill-feeling that shuts the pockets of nonmembers. Never before has it shown such arrogance and self- fancied superiority. It grasps the College Press and endeavors to rule in all. It does not deign to show its credentials, but clutches at power with the silence of conscious guilt.

(pages 65-69)

Where did George Douglas Miller’s money come from and how did it happen that he owned the land around the Tomb? My surmise is that Mr. Miller was acting as a beard for the Skull & Bones Trust. The main front man for the Order’s activities in New Haven since the mid 1850s, Mr. Gilman, had moved on in the early 1870s to serve as the first President of the University of California in 1872.

The Boodle Boys, as Skull & Bones members were being called at the time, needed a new front man and prevailed upon the obliging Mr. Miller. George spent his first year after graduation, 1871, working in the college library system — similar to Mr. Gilman’s return to Yale. He then went off into the world but he didn’t really get all that far and soon came back to New Haven. Once back in town, George soon began to buy up the property around the Tomb and served as a secretary for a local utility.

He held many of his positions from his association with Bonesman W.W. Phelps, who was the son-in-law and estate trustee of John Sheffield the benefactor of Sheffield Scientific School (SSS). Phelps was a congressman, US Minister to Austria and Germany and a very successful business man. He was on the Board of Directors of the National City Bank, The Second National Bank of NY, the United States Trust Company, nine railroad firms and others. Mr. Phelps was an incorporator and trustee for many years of Sheffield Scientific School, which was phased out in the 1950s and became officially part of Yale but with the Trust still exercising control over the land.

Back in 1911 when Miller’s money ran out, the Order had assumed the Presidency of Yale for over 20 years and in the Treasurer’s office for over 40 years. They kept this influence into the 1970s through personnel in powerful positions and the distribution of oil monies. And — the great Gothic Yale University was built.

Why spend theirs, when it could all so easily be done with other people’s money?

And Bones wouldn’t get the rap for being too haughty and powerful.

The secret society holdings are now little private islands surround by the burgeoning Yale University.

Why George Miller left New Haven is unrecorded, he spent his life after New Haven as an international traveler and dabbled some in real estate in Albany, New York. He didn’t pass on a large estate. The only thing that a grandchild remembers are trips to Deer Island and something called Miller’s Folly — some strange building that their grandfather had owned.

Miller’s Folly was a famous spite building in Albany, New York, where George, described as “an eccentric man of means,” lived in a fashionable part of town.

The Hampton Hotel a fashionable destination place in Downtown Albany at State and Broadway and “was noted in the 1920’s for its roof gardens, which offered a romantic view of the city and the river.

“George built a building on a very small piece of property that wasn’t large enough to be occupied but tall enough to block the hotel’s vistas. George expected the hotel owners to pay him money to reclaim their scenery. Instead, the Hampton built higher, so did George!

“The Hampton closed its roof and turned it into guest rooms. George’s building, never finished, with no stairs to its upper stories, became a home for pigeons, unused for a generation, a monument to perversity … .”

* *

*

Sources other than noted in text:

The Campus Guide - Yale University, Pinnell, Patrick

New Haven - A Guide to Architecture and Urban Design, Brown, Elizabeth Mills

Journal of the New Haven Historical Society - Fall 1998

O’ Albany, Kennedy, William