*

*

CROTONIA was certainly one of the first of the Yale societies. Little is known of it but it serves us here, for just as Wolf’s Head was the product of a wave of protest against the things for which Skull and Bones and Scroll and Key stood in 1883, so the first society to enjoy a long and distinguished life at Yale was started, in part, as a protest against the ways of Crotonia.

Linonia, organized in 1753, was apparently a “crusading” movement designed to bring more democracy to the College. One reads this between the lines of the brief story of Linonia’s origin (the italics in the following quotation are the writer’s): “Of the class which graduated that year [1754], numbering 17 in all,” says the author of Four Years at Yale, “one only belonged to the society [Linonia]. He was the seventeenth on the list-the names at that time being arranged according to the ‘gentility’ of the families they represented, instead of alphabetically.” Crotonia lived on for a few years only, while Linonia came into blossoming days and survived, finally only as a shell of former glory, for over a hundred years.

Linonia, however, was at first closed to freshmen, who “in those days of servitude” were never “admitted to any Society whatever”; and in 1768 Brothers in Unity was founded, definitely a crusading movement. We are told that it was organized “by 21 individuals in the four classes of [17]68, ‘69, ‘70, and ‘71 — seven being upper-class men who seceded from Linonia, and the remaining 14 being Freshmen, who were of course neutrals.” The hero of this movement was a freshman “who stood up for the dignity of his class; and having found two Seniors, three juniors and two Sophomores, who were willing that Freshmen … be admitted to a literary Society, he, with thirteen of his classmates fought for and established their own respectability.” Brothers in Unity forced the pace on Linonia, just as Wolf’s Head did later on Skull and Bones and Scroll and Key. Linonia opened its doors to the freshmen and thereafter for many years the two societies competed on a basis of equality.

Both Linonia and Brothers in Unity were secret societies; but their secrecy never reached the dignity of “poppycock “ — the generic term adopted later by the Yale undergraduate to denote all the elements in the secret society system to which he objected. The chief competition between these societies was in the matter of numbers, each attempting to get “the largest number of the incoming class.” Such rivalry in secrecy as existed was a rivalry between two groups of “ins,” stimulated to a friendly game of hide-and-seek, it being thought “a great — as it was an infrequent — triumph for a man to find out the name of the president or other officers in a rival society.” Both societies, too, had much to engross their attention besides the preservation of mystery. They served an important function in a College still inadequately organized. The accumulation of books was begun by them at a very early period; and by 1870, the number of books in each of the two libraries had reached approximately thirteen thousand. The societies also had reading rooms, which were in general use. In addition, the meetings in their halls, while in part devoted to the popular “pea-nut bums,” initiations, elections and the like, included also formal and informal debates, the delivery of orations and the reading of essays and poems, all so much the vogue in those times; and in their hey-day — after 1825 — the societies occasionally put on “exhibitions”: “a dramatic poem, a tragedy, and a comedy, all written for the occasion,” being delivered or acted, each society trying to outdo the other.

They were general societies in the truest sense of the word, and lived for many years without creating a need for reform.

A third important society was founded in 1779 — the Yale Chapter of Phi Beta Kappa. It was not, apparently, a crusading movement, for it did not compete with the existing societies. It was a national society, giving the “bulk” of its elections to the juniors during the third term, as the senior societies do to this day. Admission to the Society was considered “one of the greatest honors in college”; and in spite of stray cases of personal prejudice and personal favoritism, scholastic achievement was the sole criterion for membership, “the society confining its elections pretty closely to the list recommended it by the faculty, in response to its own application therefor.”

Phi Beta Kappa also had important educational activities, supplementing, like those of the general societies, only more seriously, the aII-too-rigid curriculum of the day. “The exercises consisted of an oration and a debate. … The day after Commencement, it was customary to hold an ‘exhibition,’ when two orations were delivered by tutors or other graduates, and a debate was engaged in by four undergraduates.” As these exhibitions gradually grew in interest and importance, it was decided to make them public, “and in the 42 years, 1793-1834, there were only 12 Commencements when the Society failed to display itself.” Like Linonia and Brothers in Unity, Phi Beta Kappa was an institution with an important private and public life in the College.

It was, however, a secret society; more secret — though in exactly what manner we are not told — than the general societies and hence more open to the temptations of generating “poppycock.” Certainly its secrecy was the secrecy of a small group of “ins” against a much larger group of “outs”; and as was to happen so often and so notoriously later on in the case of Skull and Bones and Scroll and Key, “poppycock” was accompanied by its corollary-attacks of a physical nature by the “outs.”

In the history of Phi Beta Kappa there is record of at least two breakings-in by the “neutrals” of the College, acting, we are told “under the united influence of envy, resentment and curiosity.” In 1786 three seniors broke open the door of the secretary’s study and “feloniously took, stole, and carried away the secretary’s trunk, with all its contents.” They were discovered, the papers returned and the thieves appeared before a general meeting of the society with a “voluntary” written confession, swearing never to divulge whatever secrets they had discovered. A year and a half later the trunk was once more raided and its contents stolen, the perpetrators, this time, never being discovered.

But about 1825 a much more serious event took place. “A clamor against Masonry and secret societies generally… swept over the country.” It seems to have swept through the American colleges as well and to have resulted in the removal of its secret character from Phi Beta Kappa. “With its mystery departed its activity also; and for forty years past” — the statement is from Four Years at Yale, published in 1871 — “it has been simply a ‘society institution’ possessed of but little more life than it claims to-day, though membership in it was thought an honor worth striving for until quite a recent period.” By 1884, when the Founders of Wolf’s Head were getting ready to graduate, Phi Beta Kappa was dead. The College press of the time contains reports of the efforts made by the Yale faculty to revive it. It was dead, however, past all saving except as a symbolic institution.

In 1832 with the founding of Skull and Bones begins the era of the senior societies of the type which existed in 1883. Skull and Bones was organized “by fifteen members of the class which graduated the following year” and was, in all probability, an “outs” movement, it being recorded that “some injustice in the conferring of Phi Beta Kappa elections seems to have led to its establishment.” It was not a crusading movement unless — and this may well be possible — the need of the human animal for secrecy and mystery is a real need which must be satisfied. The elimination of these elements from Phi Beta Kappa-the only important grouping in senior year at this time except Chi Delta Theta, which was distinctly literary — may have left a gaping void. Certainly, like all new institutions, Skull and Bones was not taken seriously at first, being “for some time regarded throughout college as a sort of burlesque convivial club.” Certainly too, there is no evidence of any very serious purpose behind its founding. In fact all of the evidence points to its being a group of congenial individuals enjoying, behind their closed doors, a rather riotous good time.

The same elements seem to have motivated the founding of Scroll and Key in 1841. It was definitely an “Outs” movement, “its founders not being lucky enough to secure elections to Bones.” But unlike Skull and Bones which had created an organization quite different from Phi Beta Kappa and not in competition with it, Scroll and Key, at least in the eyes of the College, set out from the beginning to rival the older society on its own ground. “Its ceremonies, customs and hours of meeting were all patterned after those of Bones, as well as its manner of giving out elections.” That it was considered a “sour grape” society is indicated by the burlesque in The Yale Banger of 1845, in which the Keys scroll bears the legend, “Declaration of Independence and Rejection of the Skull & Bone,” and has for its Great Seal “a view of the historical fox reaching after the equally celebrated grapes.” This, the author of Four Years at Yale remarks, “probably represents, with substantial accuracy, the motive which originated Keys.”

Even more than Skull and Bones the new society had hard sledding at first, failing on at least four occasions prior to 1851 to make up its full quota of fifteen, the number in 1850 falling as low as seven; but like Skull and Bones it seems to have had no important purpose of existence other than pleasant social intercourse.

Being thus limited, these two societies were in a more precarious position than the older societies which had had definite activities, intellectual and otherwise, within and without their halls. Their very secrecy was a temptation and a handicap. It would seem that at first — during the days of their youth, ten, twenty years after their respective foundings — they were merely negatively mysterious. Their members, it seems, said nothing about their activities inside their buildings and concealed the arrangement of rooms and furniture. They used their moments of public appearance to strut a bit before they retired for another year into their “ impenetrable mystery.” They wore their badges merely as symbols of membership and took themselves more or less lightly as human beings in a human world.

But with no relation to the world except the self-imposed duty of perpetuating the species, and no formalized basis for choice other than a social one, these societies fell, after a while, into the temptation of using what they had most of — their mysteries and ritual — to startle the College into taking them seriously. From a negative manifestation of mystery they gradually turned to a positive manifestation; and to the ever increasing ranks of the non-society men — the College was growing slowly, but steadily — it appeared each year that the members of these societies were becoming more self-conscious in their position as the “elect” of the College; were interfering more, as societies, in College affairs; and, in general, were thrusting themselves too much upon the attention of the College world.

By 1873 the word “poppycock” was in current use and the “god” who had started life so modestly had become great. But already in 1870 he was strutting and had been strutting for some years. The elements which had gradually come to constitute his most objectionable features will be familiar to all, for many of the hydra-heads have not been severed even to this day, and some which were once severed have grown back again.

It is to be supposed, since there is no evidence to the contrary, that from the beginning the members of both Skull and Bones and Scroll and Key wore their badges on their neckties. But by 1870 the light-hearted wearing of a symbol of membership had become a solemn ritual surrounded by ritual. “This badge is constantly worn by active members,” says the author of Four Years at Yale (from which volume many of the preceeding[sic] quotations have been taken), “by day upon the shirt bosom or necktie, by night upon the night dress. A gymnast or boating man will be sure to have his senior badge attached to what little clothing he may be encumbered with while in practice; and a swimmer, divested of all garments whatever, will often hold it in his mouth or hand, or attach it to his body in some way, while in the water.” And as for anyone touching the pin or speaking of it or of the society, the words of the Horoscope, written much later, vividly describe the result: “[the society men] rise up abruptly, put their ears behind their beads and sneak off.”

A similar ritual was built up around the society buildings: the mystery that might rightly have attached to the four walls of the meeting place being extended to unwarranted distances. The impressive Skull and Bones tomb was erected in 1856, and Scroll and Key inhabited, until the completion of their fine hall on College Street in 1870 rooms “in the fourth story of the Leffingwell Building, corner of Church and Court Streets, across from the Tontine Hotel.” We are not told directly that the entire Leffingwell Building was held sacred; but we know that by 1870 the senior society men had progressed to the length of at times refusing “to speak while passing in front of their hall” and even “in some cases [of refusing] to notice a neutral classmate whom they may chance to meet after eight o’clock of a Thursday evening.”

Such items of ritual, inasmuch as they related specifically to society paraphernalia, might not have been deemed offensive by the “neutrals” of the College and might have been without harmful results had they been restricted at this point. But once embarked upon, the habit of flaunting their special position in the face of the College grew upon the society men of successive classes like the growing hold of the drug habit.

In 1867 an all-time “high” for the period up to 1870 had been reached. In that year the College, which was apparently not too much concerned over bad manners on the part of senior society men where their pins and buildings were concerned, was distinctly shocked. We know one of the causes. “Two Bones men,” we read, “brought from their meeting a sick classmate and put him to bed in his room, without paying any attention to his neutral chum who was there present, though he was also a classmate with whom they were on friendly terms.” But there must have been other incidents which have not come down to us, for the young author of Four Years at Yale, an undergraduate at this time, speaks of “exaggerated secrecy” as “a modern outgrowth,” and refers to 1867 as the year of its “highest pitch.” He indicates clearly that the College did not take it lying down and that as a result of the furore the senior society men thereafter “conducted themselves much more sensibly.”

But this temporary recession of the tide was to be followed by new “highest pitches.” It is easy to imagine the process, for ritual is a coral growth: new ceremonies are added, but few are ever cut away. With the intense rivalry that existed between Skull and Bones and Scroll and Key the inventive genius of the immature youngesters[sic] of the successive delegations must have been continuously at work. They took what they found after their election and then, consciously and unconsciously, set about devising new ways and means of impressing the underclassmen. They invented new taboos to emphasize a superiority they may or may not have felt at first. Later, by a boomerang effect, the taboos became hourly proof of an existing superiority, till it came to be believed. Ultimately, they and all those with whom they came in contact were unhappily aware of a chasm between the “elect” and the “non-elect.”

The proof of the process is partly illustrated by a story appearing in an 1890 Buffalo, New York, newspaper. The story contains no hint as to the date of the incident, though it is evidently ancient history. It may be apocryphal. It is illuminating, nevertheless. As in the 18 67 incident a member of Skull and Bones was lying sick in his room at the hour of the regular Thursday evening meeting. His “neutral” roommate was in attendance. Members of Skull and Bones made their appearance; but this time their care and attention was not limited to a putting to bed and a departure. The technique had become enlarged. In one-hour shifts the members of the delegation came to sit by the sick man’s bed. They ignored the roommate completely and their relation with their brother member was that of the deaf and dumb.

This particular story ended happily. After the second visitation the roommate bolted the door and stoutly informed the next arrival that no deaf-mutes need apply.

It was not to be expected that the College “neutrals,” already at a disadvantage through their position as “outs” and sometimes smarting under a sense of injustice, should have remained inhibited in the expression of their feelings or that they should always have been as restrained as the roommate of the deaf-mute invasion.

Each “highest pitch” on the part of the society men was met by a corresponding “highest pitch” counter-activity on the part of the enemy, this activity taking on forms ranging from cat-calls and physical violence to diatribes in anonymous pamphlets and bitter complainings in such College publications as might by chance become available.

An entirely unofficial institution, first known as “Bowl and Stones” and later as “Bull and Stones,” was the rallying ground for the attacks. Four Years at Yale gives us the picture for the years 1865-1869. “It is in senior year alone,” says its author, “that the neutrals largely outnumber the society men, that they have nothing to hope for in the way of class elections, and that they are not overawed by the presence of the upper-class men. These circumstances combine to foster in some of them a sort of reckless hostility toward these societies. … It was in the class of ‘66 that this hostility first definitely displayed itself, in the institution of a sort of mock ‘society’ called ‘Bowl and Stones” the name being a take-off on that of Bones, and the duties of its members being simply to range about the colleges at a late hour on Thursday night, or early on Friday morning when the senior societies disbanded, singing songs in ridicule of the latter, blocking up the entries, and making a general uproar. The refrain of one song, to the tune of ‘Bonnie Blue Flag,’ was ‘Hurrah! Hurrah! for jolly Bowl and Stones’; of another to the tune of ‘Babylon,’ ‘Haughty Bones is fallen, and we gwine down to occupy the skull.’ … In the class of ‘67 they were at their worst, and wantonly smashed bottles of ink upon the front of Bones hall and tore the chains from its fence.”

By the early 1870’s “Bowl and Stones” had become “Bull and Stones,” a well established institution occupying a definite and permanent place in the minds of the undergraduate “neutrals” and the object of constant comment by them. The Naughty-Gal All-Man-Ax, for example, devoted much time and space in its issue for 1875 to the origin-entirely imaginary, of course — of this Yale institution. “Of all the college societies now in existence,” it says, “Bull and Stones is the oldest. Before even Hasty Pudding or Phi Beta Kappa were thought of, this fraternity could number its years by the score. Bull and Stones was founded Commencement Day, 1776, by the Rev. Elisha Williams, Rector of Yale College, Ezra Stiles, Jeremiah Day (both Presidents of the University), the Governor of the State, and other prominent men … . Its hall is — no one knows where. However, there is a rumor current that the elected from ‘76 are to build a fine new hall on Hillhouse Avenue.”

In one class the “neutrals” went so far “as to procure a small gilt representation of ‘a bull’ standing upon ‘stones,’ which was worn … even in public … during the first term of their senior year.”

And in very close proportion to the widening of the taboos by the society men, the activities of the “Bull and Stones” men grew more and more violent and spread deeper and deeper among the “neutrals” of all classes.

The Yale News had not been founded in those days, and even if it had been it is to be doubted in view of its subsequent history whether it would have encouraged or even permitted editorials or communications on such a hush subject as the senior societies. The Yale Courant had re-acquired independent existence as an undergraduate organ in 1870; but a search in the un-indexed volumes prior to 1874-75 fails to disclose any editorial, communication or news article, or even a list of members elected, where the senior societies are concerned. And after the 1864 attack upon Skull and Bones in The Yale Literary Magazine (via the leader “Collegial Ingenuity”) had resulted in the violent war between the “neutral” editors and the Skull and Bones editors on the Board, and in the formation the same year of the unhappy “Diggers” society, “Spade and Grave,” the pages of this aristocrat of the College papers were closed forever to “Bull and Stones” material.

The discontented of the College who were not satisfied with “direct action“ but needed the printed word for the release of their emotions, were driven, therefore, to publications of their own creating. Even more than the “physical” violences which they often chronicled, the ideas expressed in these publications were effective in crystalizing[sic] and perpetuating from one class to another the antagonism to the societies and their methods.

The one and only issue of the Iconoclast, which must have startled the College when it was put on sale on October 13, 1873, was frankly directed against Skull and Bones. “Our object,” said the editors, “is to ventilate a few facts concerning ‘Skull and Bones,’ to dissipate the awe and reverence which has of late years enshrouded this order of Poppy Cock. … Our reason for doing this, is … because we believe that Skull and Bones, directly and indirectly, is the bane of Yale College. …We speak through a new publication, because the college press is closed to those who dare to openly mention ‘Bones.’”

The eight pages were full of a variety of charges. Bones, said the editors, takes upon itself to put the final stamp of approval on those whom the Class and the College have seen fit to honor: it is an insult to both Class and College. …Yale is a poor college; it cannot afford to build adequate buildings, to pay its officers properly, or even to have its magazines bound. Why? It is said that all the rich men go to Harvard. This is not so I The reason is that Bones men have “obtained control of Yale” ; “money paid to the College must pass into their hands”; no doubt “they are worthy men in themselves, but the many whom they looked down upon while in college, cannot so far forget as to give money freely into their hands.” … Again, Bones men are shown special favor by the faculty: “Is it not strange, to say the least, that on Friday the Bones men are invariably called up on the review by our Bones professor? . . .”Bones was responsible for the low state of College baseball … Bones was responsible (by implication) for the demise of the general societies, Linonia and Brothers in Unity. … Bones was responsible for everything that ever went wrong in the College-if one were to believe the editors of the Iconoclast!

And there were interminable verses:

We are not ‘soreheads.’ God forbid that we should cherish strong

Desires to be identified with principles that long

Have been a blight upon the life and politics of Yale, —

Before whose unjust aims the glow of ‘Boss Tweed’s brass would pale.

We represent the neutral men, whose voices must be heard,

And never can be silenced by a haughty look or word

Of those whose influence here at Yale could be but void and null

Did they not wear upon their breasts two crossed bones and a skull.

****

“What right, forsooth, have fifteen men to lord it over all?

What right to say the college world shall on their faces fall

When they approach? Have they, indeed, to ‘sickly greatness grown’

And must each one with servile speech them his ‘superiors own?

And after much more the “poetic” venture ends:

And if they will not hear our claims, or grant the justice due,

But still persist in tarnishing the glory of the blue,

Ruling this little college world with proud, imperious tones,

Be then the watchword of our ranks — DOWN, DOWN WITH SKULL AND BONES !”

The leading article in the Iconoclast contained also this statement: “When Skull and Bones was founded, the evil which we are about to unfold did not exist. It is an evil which has grown up-which is growing today.” It closed with a cry which was to grow persistently louder as time went on: “It is Yale College against Skull and Bones!! We ask all men, as a question of right, which should be allowed to live?” All italics, capitalization and punctuation in quotations from the Iconoclast appear in the original.

In the same college year, 1873-74, a new departure cropped up in the war between the “ins and the “outs.”

The main attack was directed this time at Scroll and Key as a result of activities which were to acquire for this society an “unsavory reputation in regard to memorabil’ thieving.” But there was also a subsidiary attack on Skull and Bones; and for the first time apparently, the attacks were carried on not by seniors and juniors as previously, but by members of the sophomore class.

The vehicle was another private publication, a pamphlet printed in the guise of an issue of the Yale Literary Magazine and identical with it in general appearance, except that the dignified and bewigged head of Saint Elihu Yale, and his feet, legs and knee breeches, were replaced by the corresponding members of a lowly bull, the cloven hoofs resting upon a floor of cannon-ball-like stones.

The title gave the tone of the whole: Seventh Book of Genesis, otherwise known as the Gospel according to Scrohleankee. It is recorded by the Naughty-Gal All-Man-Ax, for 1875, that it was written “by a sophomore in revenge for having some of his memorabilia appropriated by one of the college societies.” It is dated February 1874.

The author set forth, first, the alleged state of mind of the men who founded Scroll and Key in 1841. “Wherefore do they of Pscullenbohnes,” the founders were made to say, “for a space of nine years set themselves up for us to bow down before and worship? Behold, they are no better than we. Go to now, let us congregate together to make unto ourselves a graven image and a great mysterie. Let it be called Scrohleankee. And let us afterward take unto ourselves from Phortietoo such of them as are to be saved like unto ourselves. Also let Phortietoo dososummore unto Phortiethrie and so on until perchance by doing sosummore we may rival our enemy, even Pscullenbohnes.” “And,” said the chronicle, they did sosummore.”

The pamphlet then sketched, in an irreverent manner, the progress of “Keeze” down to the year 1872, “when one Noah, surnamed Pohrturr, was King” and the freshman “Klasuv Psevventie Psyx journed that way” and, having become sophomores, beheld “the foolishness and thomfoollerrie of the mysterie of the great Poppiekock,” and how “very many of the lesser tribes not yet within reach of the Gospel of Dososummore … cast to the dogs their natural rights and groveled upon their bellies in the dust, that, peradventure, they might be accepted.” It told how “a Nootrahl, bold and skillful, did fasten a banner by night from the top of the chief synagogue of the land … and on it was written in symbolical characters, Death to Pschullenbohnes”; how a certain sophomore, “named Arayjay,” brought down the flag and “loaned it … to a Nootrahl to keep till Xmas for an altar cloth when offering burnt offerings to Bullensthone his god”; how Scrohleankee” stole the flag from the “neutral’s room; how in revenge the “Nootrahls congregated ‘round about the new tabernacle [the recently completed Scroll and Key tomb], reviling Keeze and singing their hymns of sacrifice”; and how “Scrohleankee [did] wax exceeding wroth, and would have gone forth and slain all, but they could not.”

The story then passed to Arayjay who “vexed over the loss of his flag … cast about him what he might do.” It told how “he spake thus within himself: … ‘I will wear their pihn; yea, verily, the golden image which they worship.’ … And he did so … and … the Keeze men were black with rage … Howbeit, they did not touch him for fear of his Klasmaytes.” Finally it was told how certain men of the class of “Psevventie Psyx,” “about the fourth watch… gathered up their loins, and taking their pots came unto Keeze Hall … and behold, they wrote upon the door, in large characters, PSEVVENTIE PSYX. Then did they hastily depart … and when the Keeze men saw what was done, their fury surpassed the rage of a mad cow in her wildest cavortings … and they held Arayjay in suspicion and would have crucified him, but they could not.”

The tale ended with a parable of a ram with two horns, attacked by a he-goat with one horn, who smote the ram and broke both horns; and the parable was thus interpreted: “The ram with the two horns is Scrohleankee. The horns …are the Gospel of Dusosummore, and the doctrine of the Great Poppiekock … . The he-goat … is Psevventie Psyx … and the rest of the prophecy showeth the hostility of Psevventie Psyx to Scrohleankee with its Dusosummore and its Poppiekock, and the manner in which Psevventie Psyx will destroy Scrohleankee and exterminate it utterly.”

A few months before the Seventh Book of Genesis, another pamphlet had appeared, The Yale Literary Chronicle. The covers of the two are identical, except in color, and they are probably by the same author, for the Chronicle couches its main story in the peculiar language which was brought to such perfection in the Seventh Genesis. It celebrated, among other things, the “many jokes and tricks … the BuIlenstohnes men [did] play upon the Chosen-phew” and especially how “they did fall upon the chariot [carrying “to the Bohns men their provender”] … and … did seize the food … and that night the Pscullenbohns men went hungry to bed “ — a tale reminiscent of the incident related in Four Years at Yale: “The Stones men seized upon and confiscated for their own use the ice-cream and other good things which the confectioner was engaged in taking into Bones hall.”

The year of the Iconoclast and the Scroll and Key war was memorable, however, for another event. In May of 1874, the Yale Courant, for the first discovered time, opened its editorial and news columns to discussion and news of the senior societies.

“It would be an unpardonable oversight,” said the issue of May 23d,” to pass without notice … an event which occupies so much of the attention and interest of the college world as the announcement of elections to Senior societies.” And the elections were not only announced and Tap Day described in detail, but the Courant embarked on a long editorial discussion of the evils of the system, particularly its creation of the politician type among the undergraduates, and closed with the bold words: “May the time soon come when Yale shall be delivered of them [the politicians] and of the system which has produced them.”

Such outspokenness may have accounted in part for the quietness of the next college year. When Tap Day was approaching in May, 1875, and the Courant was once more launching its editorials, it was able to say: “The Senior society men of ‘75 have, as a general thing, conducted themselves in a non-offensive manner; a great deal of that ostentatious ‘poppicock’ which caused so much trouble with ‘74 has not been put on; in fact, the way in which they have acted throughout the year has led us to the belief that a wise choice [in the coming elections] is to be made.” But a warning was issued. “However,” said the Courant, “whether the following year is to be a quiet one or a season of Iconoclasts, bogus pins, bum thieving, etc., rests entirely with the Society men of the Senior class, and it is to be hoped that they are fully alive to the fact.”

When Tap Day was over the Courant was not satisfied and said so. The elections, on the whole, were properly given, it thought, but one man was left out of Skull and Bones “for no other earthly reason than a petty personal dislike.” “That is the sentiment,” said the Courant, “of the majority of men in the College”; and there was no lack of frankness in the Courant’s opinion of such an act. In addition there were three surprises in the elections to Scroll and Key, and while not finding fault with the men taken in, the Courant was troubled about the men omitted. “ There has been some talk,” it remarked, “about setting Spade and Grave on its legs again and we think that it would be a desirable thing if it could possibly be done … a third society is really needed in Senior year. Of course it would be difficult to start such a society, but it would surely be a success in the end, provided however, that it was a respectable organization, and not got together to ‘grind’ the other two.”

Most illuminating of all was the Courant’s news-story of Tap Day itself. “It has been handed down by tradition that Senior election night is a legitimate time for the non-society men of the Senior and junior classes to range around Bones’ Hall, and make as much disturbance and trouble as possible, and then to howl, in the college yard for the rest of the evening, the praises of Bull and Stones, interfering with the society men as they give out elections, rushing them round the campus, locking them up in the entries and building bonfires … . But this year matters have been different … . Instead of congregating around Bones’ Hall and making the welkin ring there, the crowd thronged the yard between Farnam and Durfee, eagerly comparing notes as the elections were given out, passing a few remarks upon the general make-up of some well-dressed Keys man, and rushing round to congratulate the fortunate or to sympathize with others. As the Bones’ men went around they greeted salutations from the crowd with good natured grins, once or twice answering back in a joking way; a thing never before done and which materially assisted in repressing any tendency to rowdyism.”

The Courant closed its year with another editorial: “The organizations in question propose to take in only the ‘cream’ of the class, and when the best part of that ingredient is left out, what else can be expected than adverse criticism?” It also printed at Commencement time a communication from a graduate of ‘69. “Well, really,” asks E. P. W., the graduate, “has the writer [of the Courant’s first editorial after Tap Day] come to regard an election to a society as one of the prizes?… The Alumni do not so regard it. …”And at the same time the Courant, not to be found in support of such a system, answered: “The writer has mistaken us entirely. We never said that it was an honor to receive a Senior election. What we did say, was that it is considered an honor.…’” (Italics theirs.)

But such frankness could not last. In the College year 1875-76, the Courant was once more feeding the College on a milk and water diet. There is an editorial on the society system, but the high point of criticism was that the evils were known and felt in every class. The news-story was a conventional, a fine time was had by all, and the results of the elections were “anticipated and satisfactory to the crowd and to the class.” In 1877 and 1878 reference had dwindled to a mere list of names. In 1879 even the lists had disappeared, reappearing in 1880 and 1881 and vanishing again in 1882. Courant men, strictly “neutrals” before 1880, began in that year to receive elections: one member of the board to Skull and Bones in each of the years 1880 and 1882, and one member to Scroll and Key in 1881.

One suspects a Machiavellian technique for the muzzling of the College press. At all events, with the first return to milk and water in 1876 whether by coincidence or something more, the “Bull and Stones” violences returned.

In 1870 the author of Four Years at Yale had written with a measure of pride and a larger measure of foreboding: “Not yet do they [the “Bull and Stones” men] ever attempt to break into the halls of the [senior societies].” But among the memorabilia of the year 1876-77, we find a small brown pamphlet bearing the title: “The Fall of Skull and Bones, compiled from the minutes of the 76th regular meeting of the Order of the File and Claw.” It is dated 1876, and tells the story of an alleged breaking into the Skull and Bones tomb, “File and Claw” being obviously another manifestation of the chameleon, “Bull and Stones.”

“Anyone who was noticing the Bones men of 77,” the pamphlet begins, “on the morning of Sunday, October 1st, 1876, was probably struck by the crest-fallen air which characterized all of them. … The reason for this is a simple one. As long as Skull and Bones Society shall exist, the night of September 29th will be to its members the anniversary of the occasion when their Temple was invaded by neutrals, some of their rarest memorabilia confiscated, and their most sacred secrets unveiled to the vulgar eyes of the uninitiated.”

It may have been on this occasion that the theft reported in The New Haven Register for March 7, 1887, occurred, for dates meant as little to newspapers then as now. “The original by-laws of the Russell Trust association,’” says the Register, “… were stolen from the temple on High Street by a sorehead student in 1872 or ‘73, who had failed to get into the society itself, but did succeed in getting into the building through the roof and then making away with the by-laws.”

The pamphlet says nothing about by-laws. It deals first with the details of the fortifications of the Eulogian Temple.”

“The back-cellar windows,” it says, “were fortified as follows: First … was a row of one-inch iron bars; behind them a strong iron netting fastened to a wooden frame; behind this another row of iron bars, one and one quarter inches thick; and still behind this a heavy wooden shutter.”

It then proceeds to the tale of the breaking-the outside bars cut “only after many hours of patient and cautious labor”; the long nails in the iron netting drawn “by means of a powerful claw”; the brick “damp-wall” dug away with a claw and hatchet; and the building entered “at just half-past ten o’clock” on the night of Friday, September 29th.

The Skull and Bones tomb is described floor by floor and room by room, the invaders having discovered, in essence, nothing which they might not have known or guessed before; but “for the benefit of future explorers, and as a directory for new-fledged Bones men for all time,” they give the description and include detailed floor plans. The narrative is in all ways uninteresting. It is only important in that it is the first recorded breaking into a senior society building and that the note upon which it ends — a sincere, if slightly bombastic note-fits so accurately with all else that is known of the thoughts and activities of “neutrals.”

“Before leaving the hall,” the author says, “it was asked whether we should inform other members of the college of what we had done, and throw open the hall to the public. We think no one will deny that we had it in our power at one stroke not only to take away forever all the prestige which her supposed secrecy has given this society, but to make her the laughing-stock of all college, and render her future existence extremely doubtful. But while we had no consideration for the mysterious poppiecock of Skull and Bones Society, we nevertheless remembered that some of the Bones men of ‘77 are our warm personal friends, and therefore we preferred a less radical course. To Bones as a pleasant convivial club, we have no objections. Let her live on as long as men enjoy good suppers and quiet whist. But her mystery and her secrecy are at an end, and we hope her absurd pretensions and her poppiecock are dead also.”

THROUGH all these years one can detect a distinct change taking place in the College, fostered by the faculty, but responded to readily by the undergraduates. Yale College was growing up, “hallowed institutions” were being abolished right and left and among them, in 1875, the two sophomore societies, Beta Xi and Theta Psi.

Their abolition had been mooted for a long time, the faculty merely waiting for the proper moment and excuse. It came on Monday, May 24, 1875, a few days before that so-peaceful Tap Day of the year after the Scroll and Key “memorabil’” war, though just what happened is not clear. The Courant said of the recently tapped senior society members: “The newly elected were requested to remain in their rooms all night, probably to prevent any possible repetition of Monday night’s scene”; and added, “It was no use, no one stayed in; but everyone kept sober.” The Courant also, in announcing that the freshmen had been notified by their division officers not to be initiated into sophomore societies until further notice, said: “Last Monday’s spree … was the last straw that broke the camel’s back.”

The burial of the societies was as tumultuous as their lives. Both halls were raided by undergraduates and the appurtenances-” hymn books, the archives, the old Sigma Phi curtain, the ballot box, posters and pictures “ — carried off as “memorabil’.” Most bemourned was the Theta Psi raven “imported from England and … valued at fifty dollars.” The thefts were charged to the senior societies — to Scroll and Key, “that society having an unsavory reputation in regard to memorabil’ thieving”; to Skull and Bones, “as a prominent Bones man was seen going up there Wednesday evening” and two Bones men were caught “at the doors of Theta Psi Thursday morning, and immediately ran away upon the approach of the Sophomores.”

But significant of the changing times, no one mourned the demise of the organizations. “Talk of the Faculty disbanding them has been rife at frequent periods,” wrote the Courant,” it is probably done for a good reason. … The majority of thinking men in college will not be sorry for this action of the Faculty.” The horseplay and general disorder they bred was becoming, intellectually at least, unfashionable.

Five years later when the Founders of Wolf’s Head from the class of ‘84 had barely settled themselves in New Haven as freshmen “on probation,” the freshmen societies, Delta Kappa and Sigma Epps, met a similar fate.

Like the sophomore societies these freshmen organizations had been notorious for years as riot breeders and wasters of time. The author of Four Years at Yale gives us the picture in a description that still applied in 1880: “When ‘the candidate for admission to the freshman class in Yale College’ draws near to New Haven,” he says, “he is usually accosted with the utmost politeness by a jaunty young gentleman, resplendent with mystic insignia. …” The “jaunty young gentleman” then attempted to pledge the sub-freshman to his society, which might be Sigma Epps, Delta Kappa or Gamma Nu. On arriving at New Haven the sub-freshman was surrounded by society runners. “At a sign from the first,” the account continues, it one takes his valise, another his umbrella, a third his bundle. … And before the sub-Fresh has time to protest, he is rolling along in a hack, and his new found friends are enquiring the number of his boarding house. … Sometimes the transfer to the hack is not so easily accomplished, for the runners of another society may scent the prey, rush for it, and bear it off in triumph. There are plenty of representatives from all three societies hanging about the railroad station. … They jump upon the platforms of the moving cars, they fight the brakemen, they incommode the travelers, they defy the policemen, — but they will offer the advantages of ‘the best freshman society’ to every individual ‘candidate.’”

This picture is supplemented by the Yale Courant, already, in 1872, forecasting the abolition of these societies: “If they [the freshmen society runners] do their duty as we used to do it, they must visit the depot twenty-three times a day, besides attending to the morning and night boat.” (Italics ours.)

Quite apart from all this local disorder, the vast campaign machinery that had been built up was an impossible drain on student time and money. “I was pledged while at Williston,” writes Francis Bartlett Kellogg, Founder, Of ‘83, of his freshman society experience; and this was merely typical of the general policy of sending emissaries broadcast to the prep. schools just before Commencement to pledge members — often futily and foolishly, for we have a record that, in 1880, representatives of Gamma NO were sent to the Hartford High School and there pledged all the members of the graduating class although none of them came to Yale or, it seems, had any prospect of coming.

In addition, as had been the case with the sophomore societies, the freshman initiations, pea-nut bums, and purposeless meetings and politics were seats of continuous disorder.

The excuse to disband them appeared at the freshman initiations of 18 So. These ceremonies were held in the middle of the Garfield-Hancock presidential campaign, and presidential campaigns of that day were as immature as the horseplay of the undergraduates. Yale was largely Republican. The Democratic candidates were apparently associated in Republican minds with the rebels of the Civil War. Organization for the campaign was not casual, as witness the notice in the Yale News: “Order No. 2. The University Garfield and Arthur Regiment will meet for company drill at 9:30 A.M. Saturday.” And by a stroke of fate the hall of the Jeffersonian Club, boosters of General Hancock, was just across the street from the initiation hall of Sigma Epps; and between the two halls was hung a “flag of the union with Hancock’s name across its sacred folds.”

The inevitable happened. “The initiation,” writes Frank Kellogg, “turned out to be an historical event. It rang down the curtain for the freshmen societies. Incidentally, being tossed in a blanket is rather exhilarating. The grand climax, however, came with the discovery of a rope tied to a bar across one of the front windows. Investigation disclosed that the rope extended across Chapel Street and that from it, in mid-street, hung a large American flag with the words ‘Hancock and English’ emblazoned upon it. These were the Democratic candidates for President and Vice President. Political stupidity had anchored that rope within reach of student hands which were promptly in action. The flag was quickly hauled in and as quickly torn into a thousand pieces, henceforth to function as memorabilia of a momentous occasion.”

This act, coming when the New Haven political blood was hot, assumed major political proportions.

A despicable outrage, cried the New Haven Register, Democratic. Give us the sacred pieces, shouted the Jeffersonian Club. It was an unpardonable act, said the Yale News calmly, but stop making political capital out of what was simply the act of a few rowdy Sophs at a freshman initiation. Not rowdy Sophs — upperclassmen, protested “Justice” in a communication to the News. And committees from the College waited on the Jeffersonian Club with apologies and offers of cash payment. The Register then acquired-feloniously according to the News the Sigma Epps constitution, publishing it in full. Dastardly, thieving act, howled the News, and a secret society tool The Jeffersonian Club, having turned down the cash offer and still crying for the “sacred pieces,” waited surreptitiously upon President Porter and demanded-of all things-money, which commodity “peace-loving” President Porter dug out of his own pocket to quell the uproar-one hundred and two dollars and some cents. The entire College was furious at this traitorous act of the “rebs” Then the campaign ended; and with the approval “of all thinking men” the freshman societies were abolished forever.

That is, Delta Kappa and Sigma Epps were abolished. Gamma Nu, the third freshman society, and as far as can be learned, quite as much involved as the other two in the evils of campaigning, was permitted to survive. But Gamma Nu was a “reform” society. Its founders had suffered “the fate of all reformers … despised, derided and abused.” Gamma Nu men, by and large, were “harder workers, and in proportion to their numbers … [secured] a far larger share of the substantial college awards.” Even in 1870 Gamma Nu “was sometimes favored … [by the faculty] as against the others.” But most important of all, Gamma Nu was an open society-not exactly an open club, the ideal of the College “neutrals ‘!---but still not a typical “Yale secret society.” Its survival was a symptom of the times.

Two other “immemorial traditions” were sacrificed in this period to the eradication of immaturity: the Thanksgiving jubilee, a more than usually riotous affair frequently censored by the faculty, and the custom of the senior societies of giving their elections in the rooms of the candidates.

The Tap Day tradition had already undergone one major change. Much earlier it had been the rule for all fifteen undergraduates of each senior society to march in a body to the room of each candidate where the elections were offered, the leader of the group, in the case of Skull and Bones, “displaying a human skull and bone,” and in the case of Scroll and Key, in addition to “the large gilt scroll-and-key” being borne by the leader, with each member carrying “a key some two feet in length.” This marching of an army, however, called forth the best efforts of the “neutrals” in mass formation. Free-for-alls in the rooms and entries resulted until, after a period, a major break with tradition was made and the senior society men were sent out one by one, each individual tendering an election to an individual candidate.

As we have seen this change had achieved nothing substantial and the “neutral “ activities — the catcalls, bonfires and kidnappings — grew burdensome. Daylight and supervision-probably by the faculty — were required. The rites were, therefore, transferred to the Campus, to the corner under the elms next to the Chapel, and the Tap Day known to most living Yale men and objectionable to so many of them, came into existence.

Under the impact of all these abolitions the “Bull and Stones” violences dwindled. We know that the breaking into Skull and Bones —” this unprecedented vandalism “ — was followed “in 1878, by another set of marauders defacing with paint both Senior buildings,” that “the offenders were tried in the City Court” and that they “escaped free of fine or imprisonment, through technicalities.” We know, too, that in the same year, probably as a part of this same anti-society wave, a supplement to the Yale Year Book was devoted in part to a cut of the Keys scroll, with key-crossing, sealed with the “Great Seal “ — the fox and grapes view — and bearing the legend, obviously an imitation of the Banger burlesque already referred to: “Declaration of Imbecility and Rejection of Skull and Bones.” The accompanying letter-press reads: “The club occupying the so-called striped zebra Billiard Hall … after acting in the most unaccountable, ungentlemanly and underhand way during the past year, decided not to permit their cut to be used by anything except their own masterpieces of publications as the Yale Index. ... The following cut has been agreed upon by the dub as a proper heading for all college papers except the enterprising (1) valuable (!) yea, PRICELESS (!!) Index.” (Italics, etc., in the original.)

But after 1878 there seems to have been a cessation of physical violences and less of the old childish forms of attack.

“What were the ‘Bull and Stones’ activities in your time?” was the question put in the recent questionnaire to the living members of the first three delegations to Wolf’s Head who, together, cover the college generation, 1879-1885. “None,” is the substance of the statements of the nine men who answered: Frank Bartlett Kellogg and Frank Cunningham; Founders, of ‘83; Franklin Davis Bowen, Henry Raup Wagner and Harry Augustus Worcester, Founders, of ‘84; and Albert Heman Ely, Lafayette Blanchard Gleason, William Procter Morrison and William T. G. Weymouth, of ‘85; either by direct statement, or indirectly by failing to answer the question. Weymouth says, “I hardly remember the name,” and Gleason adds, “Not until the meeting of the Senior class in 1884.”

This does not mean, however, that the “poppycock” of the society men had diminished in intensity or scope or that the College had grown reconciled to it.

We read in the New Haven press of those days of an operation in Bridgeport, Connecticut, upon a Skull and Bones man in a very serious condition after having swallowed his society pin: humorous, if it were not so sad; and Frank Kellogg writes:

“I recall a prank of Sophomore year. The D’Oyly Carte Musical Comedy Company gave ‘The Pirates of Penzance’ in New Haven. The pirate king wore a Napoleon hat with a skull and cross bones emblazoned on it. I enlisted the co-operation of Ted Buell and Charlie Foote in my plot and we visited the ‘king’ at his hotel. We told him that it would make a local hit if he would put ‘322’ below the death’s head. Then we went to the evening performance and sat in the front row of the balcony. When the ‘king’ appeared he had the mystic number on the hat all right.

“I don’t suppose the singer noticed that several students in the audience got up and left the hall. Much less did he know that they were ‘Bones’ men. However, we did, and got quite a kick out of it, but more especially out of the universal grin on the faces of all the other Yale men in the audience.”

But whether these activities and all they typify were confined to Skull and Bones men, or were affected by Scroll and Key men as well, and whether by all fifteen men in each society or by a few only, there is no direct evidence to show. Scroll and Key as a rule seemed to confine its unpleasantness to “memorabil’” raids and such, leaving to Skull and Bones the development of “haughty manners.” In all probability, it was the old story of “high pitches” and “low pitches,” for we know that the society men of ‘82, like their predecessors of a few classes after the “highest pitch” of 1867, conducted themselves “ more sensibly.” That there was an immediate reaction is proven by the tidal wave of antagonism that threatened to overwhelm the societies in 1883 and 1884.

The forerunner of this wave was a “ daily anti-senior society newspaper … vigorously conducted so as to thwart the society men in every way.” No copy of this publication has been discovered; but the fact that it was issued daily proves that its attack was, like that of the Iconoclast, general and not specific, and that the antagonism behind it unlike the quickly released antagonisms of the Iconoclast, the Seventh Book of Genesis and the Fall of Skull and Bones, was something functioning twenty-four hours a day.

The wave itself, however, was characterized by a rebellion in the ranks of the senior societies themselves, as is evidenced by an “ elaborate pamphlet from a man who had belonged to the societies from each year, from first to last,” and who, in spite of these affiliations, “ sought to prove that the whole system was pernicious and should be abolished.” This was alarming enough, but worse followed. The crusade against the societies, until then confined to the Campus activities of the “Bull and Stones” men and the presentation of views in special publications of limited circulation, spread violently outward and “was transferred to the columns of prominent metropolitan journals.” The alumni bodies were infected: “ alumnus and undergraduate emulated each other in striving to point out the enormities committed by the societies,” and before the astonished eyes of the world-at-large, and aided and abetted by editors forever welcoming dissension at Yale to increase their circulation, “the good name of the University … [was) dragged through the mire by her own sons.”

The situation affected all Yale men, but from the point of view of the harassed societies the immediate danger lay in the fact that the attacks upon them had lost their informal and indirect characteristics. A few isolated expressions of adverse opinion could be ignored by the Yale authorities as unrepresentative. “Bull and Stones” physical violences could be cried down as immature horseplay of undergraduates and counter-attacked as clean-cut violations of law. But when “the faculty and corporation were directly appealed to” by the enemies of the system, then the situation was obviously out of hand. It was entirely possible that, legally and drastically approached, the faculty and corporation would be driven into legal and drastic action.

We have this general picture on the unimpeachable authority of John Addison Porter, prominent Yale and Scroll and Key man, in his article in the New Englander for May, 1884, “The Society System of Yale College.” It is to be gathered directly from what he says and indirectly from what he implies. The vital nature of the question is to be read in his choice of vehicle: a publication traditionally devoted to Yale matters of the highest importance. The quality of the danger appears in his statement that whereas “the societies have never yet : been forced to … offer explanations to their assailants, and it is extremely improbable that they will ever condescend to do so,” nevertheless the occasion has now arisen “for plain words between man and man … the time for delay, for allowing things to ‘adjust’ themselves, would appear to have passed.”

“Whether the Yale Societies are guilty or not of the charges made against them,” says Mr. Porter,” is not the first question. … The very fact that almost every year the students are more or less divided on this score, that twice within the past ten years the faculty have thought necessary to exercise their rarely used prerogative of suppressing time-honored customs the Freshmen and the Sophomore Societies augurs that germs of further dissension may exist fatal to that harmony which is indispensible(sic) to the greatest usefulness of the University.”

He then proceeds to a series of charges and answers to the charges, that may well be taken as typical of the attacks and defences of the “societies war and of their extraordinary futility. The “neutrals were in the grip of psychological factors created, in part, by the presence and growth of “poppycock,” while the societies were unable to recognize the impossibility of a reconciliation of views without a major change of policy.

Charge: “The Senior Societies … have muzzled the college press … .”

Answer: “On all the college press proper (i.e., excepting the Yale Literary Magazine) the nonSenior-society men always greatly outnumber the elect”; but “to preserve a constant equilibrium [in the College] would be simply an impossibility … if general society discussions were allowed to overload the columns of college news-papers.”

Charge: “The evil worms itself into our religious life … i.e., by estranging from their classmates the ‘deacons’ who are society men.”

Answer: “Coming merely as an anonymous and unauthenticated assertion, in the N. Y. Nation, it may be dismissed ... .

Charge: The societies are over-expensive.

Answer: No men, however bitter, have boasted that they were left out of the societies simply on this score.”

Charge: “College work deteriorates about the time the society elections are announced.”

Answer: It is “the hottest portion of the Spring. … The discerning faculty … invariably shorten the advance work and institute review lessons … . What connection there is between the societies … and deterioration in scholarship, is not patent on the surface.”

Charge: “Politics … are to some extent increased by the presence of the societies.”

Answer: “The author of Four Years at Yale, a non-Senior Society man, and not over partial to them, states in his book, ‘The part played by them in politics is simply a negative one.’”

Charge. “Favoritism rules the elections … relationships and personal friendships are acknowledged before merit.”

Answer: “Year after year the nearest relatives, sons, brothers, nephews, the most cordial friends and room-mates are left out … simply because they fall below the required standard for membership.”

Charge: “Men admit just before they join the societies … that they tend to keep the non-society men from coming back to Commencements and other reunions after graduation.”

Answer: “Yale non-society men come back to New Haven more regularly and in larger numbers than the alumni of non-society colleges.”

Admission and defence: “The societies … are tempted occasionally to abuse their privileges … . Their ‘etiquette’ … which prevents them from discussing society matters with outsiders, thus being directly opposed to wirepulling, is … commendable. When it is perverted into rudeness to strangers, or swaggering with under-classmen, it is puerile and snobbish.”

Charge in conclusion: “Society influence pervades the faculty and corporation, influencing the bestowal of prizes, appointments to tutorships, etc.”

Admission in conclusion: “If such cases can be authenticated they are danger signals of the downfall of the one society, or both.”

Defence desperate: “It is doubtful if the faculty and corporation themselves could abolish them without legal proof that they had abused the privileges which had been guaranteed them.

The immediate cause for the publication of this article was the direct, open and organized attempt, on February 1, 1884, to kill or cure the diseased society “pyramid” by the amputation of its senior society top-knot. Said The New Haven Register, in 1887, “In 1884 … opposition to ‘poppycock’ … was at its height”; and The New York Tribune, in 1896, “From time to time the opposition to the senior society system takes organized form, but perhaps the most vigorous attack … was made by the class of 1884”

The wave was breaking.

The senior class had met, according to custom, for the election of its class day committees: Promenade, Class Supper, Class Day, Class Cup, Ivy, and the election of a Class Secretary. Well beforehand, however, it had become known that after the transaction of this business, a resolution against the senior societies would be introduced. “[The movement] was fostered and conducted,” writes Lafayette Gleason, “by William McMurtrie Speer, afterwards prominent in newspaper and legal circles in New York”; and Speer had done a thorough job. “The supporters of this motion entered the meeting confident of their ability to put it through,” the Yale News says, and this is confirmed by the statement of the Horoscope of a year later: “There were a sufficient number who had promised to vote for it to make it a success.”

The society men were genuinely alarmed. One more “abolition” in a season of “abolitions” was entirely within the bounds of possibility. They themselves conducted a counter-canvass of the class insofar as their policy of never condescending to face an opponent man to man would permit them; but this policy had them at a distinct disadvantage. The mathematics of the meeting disclose two illuminating possibilities. There were 151 men in the senior class. 117 of these voted “yea” or “nay” on the anti-society motion. 117 Plus 30 equals 147. Allowing for a few natural absences, the conclusion is inevitable either that not a single member of Skull and Bones or Scroll and Key was present at the meeting or that, being present, they were too proud to vote. In either event, they were forced to rely on such allies as could be induced to support them.

The Class Day officers were duly elected, among them a number of the men to be found among the Founders of Wolf’s Head: Charles Walker, William Bristow and Charles Phelps, to the Promenade Committee of nine; William Holliday, Harry Worcester, Harry Wagner, and James Dawson, to the Class Supper Committee of five; Edwin Merritt, Henry Cromwell and Sidney Hopkins to the Class Cup Committee of three.

“The way was now clear,” says the Yale News, for Mr. Speer to introduce the following resolution, which the meeting had declined to receive before, prefering[sic] to postpone its discussion until all other business had been transacted:

“WHEREAS, The present senior society system creates a social aristocracy, exercises an undue influence in college politics, fosters a truckling and cowering disposition among the lower classes, creates dissensions and enmities in every class, alienates the affections of the graduates from the college, stifles the full expression of college sentiment by its control of the college press.

“Resolved, That we believe this system detrimental to the best interest of Yale College and injurious to, ourselves. That we request the college press to publish this resolution of the senior class. That the chairman and two others, to be appointed by him, be a committee of three to lay this resolution before the president, faculty and members of the corporation.”

Debate then followed, but true to the general policy of suppressing society news and views as far as possible, not a word appears in the College press, or elsewhere, of the sentiments expressed. We know only the outline of the parliamentary procedure: that after the resolution had been read, “Mr. Merritt “ — no other than Edwin Albert Merritt, of ‘84, a Founder of Wolf’s Head —” demanded that the mover should make known to the meeting his reasons for supporting it. Mr. Speer, thereupon, did so, when Mr. Merritt spoke at some length in reply. The debate was continued by Mr. Kinlay, for the resolution, and Mr. Judson, against.”

Then after some skirmishing — a majority vote to lay on the table having been ruled insufficient by the chair, with a two-thirds vote impossible to secure — the motion was put to a vote. The chair ruled “that the voter, on his name being called, could answer from his seat, could whisper his vote in the ear of the chairman, or could deposit a ballot in the hat at the desk”; and amid great excitement, 117 men of the senior class, one by one, recorded their vote in these varying fashions. The process was slow, with the outcome unrevealed and in doubt. At length all the votes were in and counted.

There were 67 “nays” and 50 “yeas.”

“It is a disgrace to the Yale manhood so often spoken of,” writes the Horoscope bitterly in 1885, “that the last graduating class was unable to pass resolutions condemning the methods of the two eyesores.” This from the “neutral” side. On the “society” side haste was made to follow up the advantage gained and within a few hours almost, John Addison Porter had been spurred into the preparation and proposed publication of a “defense” of the system and was abroad on the Campus collecting his material before worse should happen.

The outcome seems to have been a complete surprise both to the two older societies and to the College. It was due, however, to the introduction of a new element. In June of 1883, eight months before, entirely unknown to the College or the world-at-large, a third senior society had been successfully founded — the society which was to be called later Wolf’s Head “ and “The Phelps Association.”

“I remember the meeting … very well,” writes Harry Wagner. “On this occasion the two older societies requested our assistance. I think that most of our members voted with them.” Lafayette Gleason says: “Speer counted upon the votes of Wolf’s Head members, as we were supposed to be organized in opposition to the two societies, but for obvious reasons, such as the Hall being under construction, etc., he did not get those votes.”

The shift of fifteen votes would, of course, have reversed the “yeas” and “nays” and brought victory to the proponents of the resolution, so that the Founding may be said to be directly responsible for the outcome. But while some of the fifteen Founders must have voted as they did from loyalty to a system of which they were now a part or from a feeling that the system was too entrenched to be affected by a mere vote, nevertheless, from an historical perspective the reason for the defeat appears to lie much deeper.

The Founders of the new Society had been, of course, of the great body of the College “outs.” For this very reason they had not been bound by tradition and were able with dear eyes to discern the defects in the existing system, and to attempt its cure through the introduction of new and progressive elements rather than through the over-drastic process of the axe. Not by accident had they gathered into the platform of their institution the spirit of the ideas expressed over long years by the “neutrals” of the College-the spirit of the Courant’s description of that one peaceful Tap Day after the bitter Scroll and Key memorabilia war: “As the Bones men went around they greeted salutations from the crowd with good-natured grins, once or twice answering back in a joking way; a thing never before done …”; the spirit of the Courant’s “third society” proposal: “a respectable organization … not got together to ‘ grind ‘ the other two “; the spirit of the constructive elements of the Iconoclast, the Seventh Book of Genesis and the Fall of Skull and Bones.

In addition, like the founders of Linonia and Brothers in Unity, they had embarked upon their venture with something of a crusading fervor — “ to bring more democracy to the College.” As a first witness of this, unlike the members of Skull and Bones and Scroll and Key who were skulking in their tents — haughtily absent or more haughtily present but not voting — the fifteen members of the new society were full participants in the meeting with their non-society classmates.

It would not have been possible in the course of a bitter and long debate to have kept the basic principles of the founding of the new Society wholly hidden. Wolf’s Head, at this time, was still without a name; its building was no more than a foundation covered with snow; but its existence was known by this time and its membership, in part at least, identified and something of the ideas behind its founding must have percolated into the College. When, therefore, Edwin Merritt spoke “at some length” in defense of the society system — or more probably in defense of a society system in which a sense of humor would play a large part and “poppycock” none at all — it is impossible not to believe that he was listened to by his classmates with deep interest as the possible prophet of a new order, or that ‘votes — whether of some of the Founders or of the “neutrals” — previously “promised” to Speer were changed under the persuasiveness of the new idea.

More than this, the very presence of the members of the new society at the meeting, taking part in the debate and registering their votes, must have been a happy and effective testimonial of the possibility of a new order.

Pages 17-67 of The Founding of Wolf’s Head, by John Williams Andrews.

The Phelps Association, 1934.

* *

*

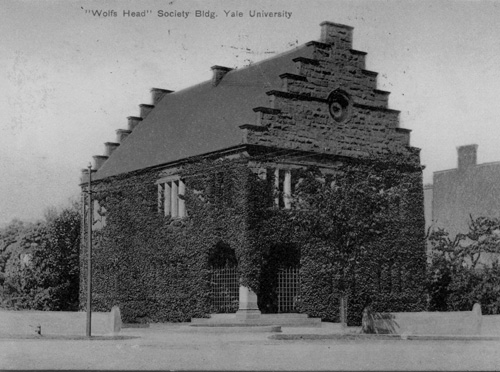

The Wolf’s Head Society’s Original House circa 1900

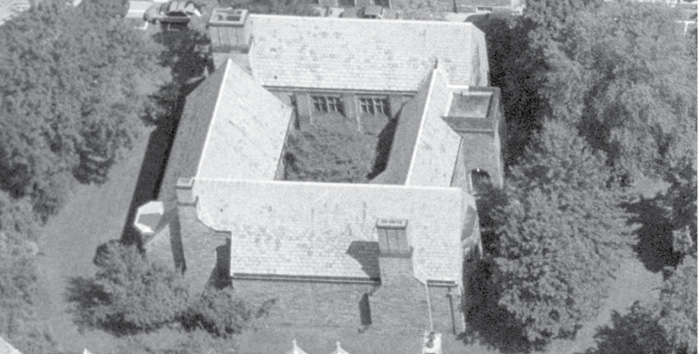

The Current Wolf’s Head Society compound at Yale. The property is completely surrounded by a high stone wall. the back building appears very chapel-like.

The Current Wolf’s Head Society compound at Yale. The property is completely surrounded by a high stone wall. the back building appears very chapel-like.

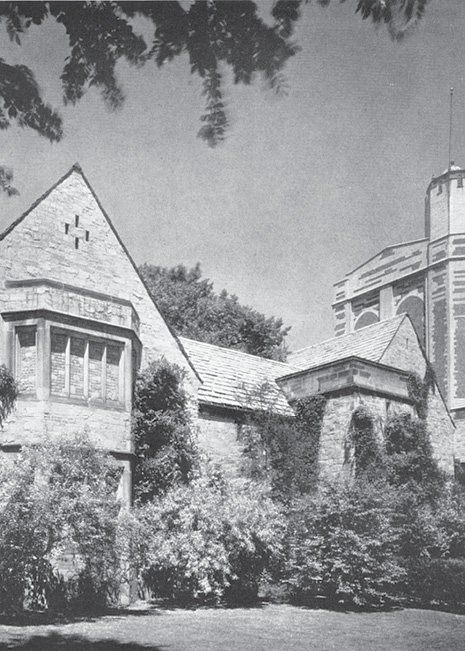

Wolf’s Head Society buildings from the front and inside the wall. Notice bricked-up windows.