IN CONVERSATION WITH DAVID BARSAMIAN, SEPTEMBER 2002.

Based on conversations with David Barsamian in Albuquerque, New Mexico, and Las Vegas, Nevada.

It’s been nineteen months since our last interview. Can you update me on the criminal case filed against you in a district magistrate’s court in Kerala for your book, The God of Small Things? The charge was ‘corrupting public morality’.1 What has been the outcome of that particular case?

Well, it hasn’t had an outcome. It’s still pending in court, but every six months or so the lawyer says, ‘There’s going to be a hearing; can you please come?’

This is one of the ways in which the state controls people. Having to pay a lawyer, or having a criminal case in court, never knowing what’s going to happen. It’s not about whether you get sentenced eventually or not. It’s the harassment. It’s about having it on your head, about not knowing what will happen.

More recently you’ve been charged and found guilty of contempt of court by India’s Supreme Court…

It’s McCarthyism—a warning to people that criticizing the Supreme Court could jeopardize your career. You’d have to hire lawyers, make court appearances—and eventually you may or may not be sentenced. Who can afford to risk it?

Tell me about Aradhana Seth’s film, DAM/AGE2

Usually when people ask me to make films with them, I refuse. The request to do DAM/AGE came just after the final Supreme Court hearing, when it became pretty obvious to me that I was going to be sentenced, one way or another. I didn’t know for how long. I was pretty rattled and thought that if I was going to be in jail for any length of time, at least my point of view ought to be out in the world.

In India, the press is terrified of the court. So there wasn’t any real discussion of the issues. It was discussed in a ‘Cheeky Bitch Taken to Court’ sort of cheap, sensationalist way, but not seriously. After all, what is contempt of court? What does this law mean to ordinary citizens? None of these things had been discussed at all. So I agreed to do the film simply because I was nervous and wanted people to know what this debate was about.

In a very moving segment of the film, you discuss a man named Bhaji Bhai. Can you talk about him?

Bhaiji Bhai is a farmer in Gujarat, from a little village called Undava. When I first met him, I remember thinking, ‘I know this man from somewhere.’ I had never met him before. Then I remembered that a friend of mine who had made a film on the Narmada years before had done an interview with Bhaiji Bhai. He had lost something like seventeen of his nineteen acres to the irrigation canal in Gujarat. And because he had lost it to the canal, as opposed to submergence in the reservoir area, he didn’t count as a project-affected person and wasn’t compensated. So he was pauperized and had spent I don’t know how many years telling strangers his story. I was just another stranger that he told his story to, hoping that some day someone would intervene and right this great wrong that had been done to him.

Women seem to be central to the struggle in the Narmada valley. Why do you think women are so actively engaged there?

Women are actually actively engaged in many struggles in India. And especially in the Narmada valley. In the Maheshwar dam submergence villages, the women of the valley are particularly effective. Women are more adversely affected by uprootment than men. Among the adivasi people, it is not the case that men own the land and women don’t. But when adivasis are displaced from their ancestral lands, the meagre cash compensation is given by the government to the men. The women are completely disempowered. Many are reduced to offering themselves as daily labourers on construction sites and they are exploited terribly. Women often realize that if they’re displaced, they are more vulnerable and therefore they understand the issues in a more visceral and deeper sense than the men do.

You write in your latest essay ‘Come September’ that the theme of much of what you talk about is the relationship between power and powerlessness. And you write about ‘the physics of power’.3 I’m interested that you use that term, physics. It kind of connects with the mathematical term you used in another of your essays, ‘The Algebra of Infinite Justice’. What do you have in mind there?

Unfettered power results in excesses such as the ones we’re talking about now. And eventually, that has to lead to structural damage. I am interested in the physics of history. Historically, we know that every empire overreaches itself and eventually implodes. Then another one rises to take its place.

But do you see those excesses as inherent in the structure of power? Are we talking about something inevitable here?

Inevitable would be too fatalistic a term. But I think unfettered power does have its own behavioural patterns, its own DNA. When you listen to George Bush speak, it’s as though he has no perspective because he’s driven by the crazed impulse of a maddened king. He can’t hear the murmuring in the servants’ quarters. He can’t hear the words of the world’s subjects. He’s driving himself into a situation and he cannot turn back.

Yet, just as inevitable as the journey that the powerful undertake is the journey undertaken by those who are engaged in the business of resisting power. Just as power has a physics, those of us who are opposed to power also have a physics. Sometimes I think the world is divided into those who have a comfortable relationship with power and those who have a naturally adversarial relationship with power.

You’ve just spent a couple of weeks in the United States. You spoke in New York and Santa Fe, then took a driving trip through parts of New Mexico. What do you think about the incredible standard of living that Americans enjoy, and the price that is exacted from the developing world to maintain that standard of living?

It’s not that I haven’t been to America or to a western country before. But I haven’t lived here, and I can’t seem to get used to it. I haven’t got used to doors that open on their own when you stand in front of them, or looking at these supermarkets stuffed with goods. But when I’m here, I have to say that I don’t necessarily feel, ‘Oh, look how much they have and how little we have.’ Because I think Americans themselves pay such a terrible price.

In what way?

In terms of emotional emptiness. Watching Michael Moore’s film Bowling for Columbine you suddenly get the feeling that here is a country with an economy that thrives on insecurity, on fear, on threats, on protecting what you have—your washing machines, your dishwashers, your vacuum cleaners—from the invasion of killer tomatoes or evil women in saris or whatever other kind of alien.4 It’s a culture under siege. Every person who gets ahead gets ahead by stepping on his brother, or sister, or mother, or friend. It’s such a sad, lonely, terrible price to pay for creature comforts. I think people here could be much happier if they could let their shoulders drop and say, ‘I don’t really need this. I don’t really have to get ahead. I don’t really have to win the baseball match. I don’t really have to come first in class. I don’t really have to be the highest earner in my little town.’ There are so many happinesses that come from just loving and companionship and even losing.

You write in your essay ‘Come September’ that the Bush administration is ‘cynically manipulating people’s grief’ after September 11 ‘to fuel yet another war—this time against Iraq’.5 You’re speaking out about Iraq and also Palestine. Why?

Why not?

But you know that those are stories that are very difficult for most Americans to hear. There’s not a lot of sympathy in the United States for the Palestinians, or for the Iraqis, for that matter.

But the thing is, if you’re a writer, you’re not polling votes. I’m not here to tell stories that people want to hear. I’m not entering some popularity contest. I just say what I have to say, and the consequences are sometimes wonderful and sometimes not. But I’m not here to say what people want to hear.

Let’s talk a little bit about the mass media in the United States. You write that ‘thanks to America’s “free press”, sadly, most Americans know very little’ about the US government’s foreign policy.6

Yes, it’s a strangely insular place, America. When you live outside it, and you come here, it’s almost shocking how insular it is. And how puzzled people are—and how curious, now I realize, about what other people think, because it’s just been blocked out. Before I came here, I remember thinking that when I write about dams or nuclear bombs in India, I’m quite aware that the elite in India don’t want to know about dams. They don’t want to know about how many people have been displaced, what cruelties have been perpetrated for their own air conditioners and electricity. Because then the ultimate privilege of the elite is not just their deluxe lifestyles, but deluxe lifestyles with a clear conscience. And I felt that that was the case here too, that maybe people here don’t want to know about Iraq, or Latin America, or Palestine, or East Timor, or Vietnam, or anything, so that they can live this happy little suburban life. But then I thought about it. Supposing you’re a plumber in Milwaukee or an electrician in Denver. You just go to work, come home, you work really hard, and then you read your paper or watch CNN or Fox News and you go to bed. You don’t know what the American government is up to. And ordinary people are maybe too tired to make the effort, to go out and really find out. So they live in this little bubble of lots of advertisements and no information.

Third World Resurgence, an excellent magazine out of Penang, Malaysia, had a recent article on the Bhopal disaster of 1984. More than half a million people were seriously injured and some 3,000 people died on December 3, 1984, when a cloud of lethal gas was released into the air form Union Carbide’s Bhopal facility in central India. More than 20,000 deaths have since been linked to the gas.

The article features a leader among Bhopal survivors named Rasheeda Bee—you can tell from the name she’s Muslim—who lost five members of her immediate family to cancer after the disaster, and she herself continues to suffer from diminished vision, headache and panic. At the Earth Summit in Johannesburg a few weeks ago, Rasheeda tried to personally hand over a broom to the president of Dow Chemical, which has now taken over Union Carbide, and here’s what she said: ‘The Indian government has received clear instructions from its masters in Washington, DC. The [Indian] government has made it clear to us [that is, the victims] that if it comes to choosing between holding Dow [Chemical]/[Union] Carbide liable (or punishing Warren Anderson [who was the CEO of Union Carbide]) and deserting the Bhopal survivors, it will opt for the latter without batting an eyelid.’7

Even the absurd compensation that the Indian courts agreed upon for the victims of Bhopal has not been disbursed over the last eighteen years. And now the governments are trying to use that money to pay into constituencies where there were no victims of the Bhopal disaster.8 The victims were primarily Muslim, but now they’re trying to pay that money to Hindu-dominant constituencies, to look after their vote banks.

You were speaking to some students in New Mexico recently and you advised them to travel outside the United States, to put their ears against the wall and listen to the whispering. What did you have in mind in giving them that kind of advice?

That when you live in the United States, with the roar of the free market, the roar of this huge military power, the roar of being at the heart of empire, it’s hard to hear the whispering of the rest of the world. And I think many US citizens want to. I don’t think that all of them are necessarily co-conspirators in this concept of empire. And those who are not, need to listen to other stories in the world—other voices, other people.

Yes, you do say that it’s very difficult to be a citizen of an empire. You also write about September 11. You think that the terrorists should be ‘brought to book’. But then you ask the questions, ‘Is war the best way to track them down? Will burning the haystack find you the needle?’9

Under the shelter of the US government’s rhetoric about the war against terror, politicians the world over have decided that this technique is the best way of settling old scores. So whether it’s the Russian government hunting down the Chechens, or Ariel Sharon in Palestine, or the Indian government carrying out its fascist agenda against Muslims, particularly in Kashmir, everybody’s borrowing the rhetoric. They are all fitting their mouths around George Bush’s bloody words. After the terrorist attack on the Indian Parliament on December 13, 2001, the Indian government blamed Pakistan (with no evidence to back its claim) and moved all its soldiers to the border. War is now considered a legitimate reaction to terrorist strikes. Now through the hottest summers, through the bleakest winters, we have a million armed men on hair-trigger alert facing each other on the border between India and Pakistan. They’ve been on red alert for months together. India and Pakistan are threatening each other with nuclear annihilation. So, in effect, terrorists now have the power to ignite war. They almost have their finger on the nuclear button. They almost have the status of heads of state. And that has enhanced the effectiveness and romance of terrorism.

The US government’s response to September 11 has actually privileged terrorism. It has given it a huge impetus, and made it look like terrorism is the only effective way to be heard. Over the years, every kind of non-violent resistance movement has been crushed, ignored, kicked aside. But if you’re a terrorist, you have a great chance of being negotiated with, of being on TV, of getting all the attention you couldn’t have dreamt of earlier.

When Madeleine Albright was the US ambassador to the United Nations in 1994, she said of the United States, ‘We will behave multilaterally when we can and unilaterally when we must.’ I was wondering, in light of the announcement last week [on September 17] of the Bush doctrine about pre-emptive war, if that may not be used as legitimacy for, let’s say, India to settle scores with Pakistan.10 Let’s say the Bharatiya Janata Party government in New Delhi says, ‘Well, we have evidence that Pakistan may attack us, and we will launch a pre-emptive strike.’

If they can borrow the rhetoric, they can borrow the logic. If George Bush can stamp his foot and insist on being allowed to play out his insane fantasies, then why shouldn’t Prime Minister A.B. Vajpayee or Pakistan’s General Musharraf? In any case, India does behave like the United States of the Indian subcontinent.

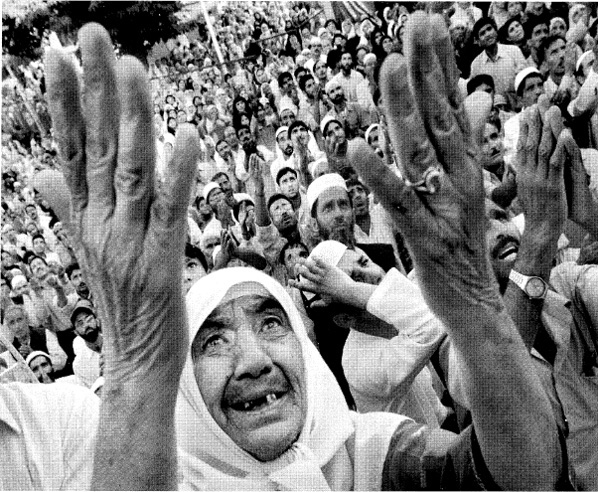

Muslims in Kashmir pray at the Hazratbal shrine in Srinagar. Photo © Altaf Qadri.

You know the old expression, ‘Beauty is in the eye of the beholder’. Maybe ‘terrorist’ is the same thing. I’m thinking, for example, Yitzhak Shamir and Menachem Begin were regarded by the British as terrorists when they were controlling Palestine. And today they’re national heroes of Israel. Nelson Mandela was considered for years to be a terrorist, too.

In 1987, when the United Nations wanted to pass a resolution on international terrorism, the only two countries to oppose that resolution were Israel and the United States, because at the time they didn’t want to recognize the African National Congress and the Palestinian struggle for freedom and self-determination.11

Since September 11, particularly in the United States, the pundits who appear with boring regularity on all the talk shows invoke the words of Winston Churchill. He’s greatly admired for his courage and he’s kind of a model of rectitude to be emulated. In ‘Come September’ you have a wry, unusual quote from Winston Churchill, that often does not get heard anywhere. Can you paraphrase it?

He was talking about the Palestinian struggle, and he basically said, ‘I do not believe that the dog in the manger has the right to the manger, simply because he has lain there for so long. I do not believe that the Red Indian has been wronged in America, or the Black man has been wronged in Australia, simply because they have been displaced by a higher, stronger race.’12

And he said this in 1937, I believe.

Yes.

You conclude your essay, ‘War Is Peace’, by wondering: ‘Have we forfeited our right to dream? Will we ever be able to re-imagine beauty?’13

That was written in a moment of despair. But we as human beings must never stop that quest. Never. Regardless of Bush or Churchill or Mussolini or Hitler, whoever else. We can’t ever abandon our personal quest for joy and beauty and gentleness. Of course we’re allowed moments of despair. We would be inhuman if we weren’t, but let it never be said that we gave up.

Vandana Shiva, who’s a prominent activist and environmentalist in India, told me a story once about going to a village and trying to explain to the people there what globalization was doing to people in India. They didn’t get it right away, but then somebody jumped up and said, ‘The East India Company has come back.’ So there is that memory of being colonized and being recolonized now under this rubric of corporate globalization. It’s like the sahibs are back, but this time not with their pith helmets and swagger sticks, but with their laptops and flow charts.

We ought not to speak only about the economics of globalization, but about the psychology of globalization. It’s like the psychology of a battered woman being faced with her husband again and being asked to trust him again. That’s what is happening. We are being asked by the countries that invented nuclear weapons and chemical weapons and apartheid and modern slavery and racism—countries that have perfected the gentle art of genocide, that colonized other people for centuries—to trust them when they say that they believe in a level playing field and the equitable distribution of resources and in a better world. It seems comical that we should even consider that they really mean what they say.

In DAM/AGE there’s an incredibly moving scene where the Supreme Court in New Delhi is surrounded by people who have come from the Narmada valley and elsewhere and are chanting your name and giving you support. There was just so much love and affection and tears came to your eyes. As I recount it, I’m getting the chills myself. It was very beautiful.

I was very scared that day. Now that it’s over it’s okay to say what I’m saying. But while it was happening, while I was surrounded by police and while I was in prison—even though I was in prison for a day—it was enough to know how helpless one can be. They can do anything to you when you are in prison.

I knew that people from the Narmada valley had come. They hadn’t come for me personally. They had come because they knew that I was somebody who had said, with no caveats, ‘I’m on your side.’ I wasn’t hedging my bets like most sophisticated intellectuals, and saying, ‘On the one hand, this, but on the other hand, that.’ I was saying, ‘I’m on your side.’ So they came to say, ‘We are on your side when you need us.’

I was very touched by this, because it’s not always the way people’s movements work. People don’t always come out spontaneously onto the streets. And one of the things about resistance movements is that it takes a great deal of mobilization to keep a movement together and to keep them going and to do things for one another. There are so many different kinds of people putting their shoulders to the wheel. It’s not as though all of them have read The God of Small Things. And it’s not as if I know how to grow soyabeans. But somewhere there is a joining of minds and a vision of the world.

‘The thing is, if you’re a writer, you’re not polling votes. I’m not here to tell stories that people want to hear. I’m not entering some popularity contest. I just say what I have to say, and the consequences are sometimes wonderful and sometimes not. But I’m not here to say what people want to hear.’

‘When people try to dismiss those who ask the big public questions as being emotional, it is a strategy to avoid debate. Why should we be scared of being angry? Why should we be scared of our feelings, if they’re based on facts? The whole framework of reason versus passion is ridiculous, because often passion is based on reason. Passion is not always unreasonable. Anger is based on reason. They’re not two different things. I feel it’s very important to defend that. To defend the space for feelings, for emotions, for passion.’