The Field

By Bonnie Tamblyn

Mother and Mentor

Out beyond ideas of wrongdoing and rightdoing, there is a field. I’ll meet you there. When the soul lies down in that grass, the world is too full to talk about.

—Rumi

Come, my children, and I will tell you a story of deep listening, of our connections to our instinct and the roots we all share as humans. It is our gift of cognition and recognition; that moment when something stirs inside and strikes us as different—notable, time out of time. We are instinctive creatures, after all. The companion to our instinct is our intuition, and the companion to our intuition, if we but heed it, is attunement—a deep listening to our shared story, the moment when we meet out in that field with a heightened sense of place, self, and other.

It’s a chilly dawn in 2017, and the morning light is beginning to filter in through the cracks of our rugged yurt nestled high up on the Dragon Ridge in the upper Ojai Valley. I’ve come for a retreat at the Ojai Foundation where I have taught experiential education for more than twenty years. I am being joined here by my fellow teachers, healers, and facilitators from all over the world, who offer a circle way called Council: a dialogical practice for adults and children which supports self-reflection and discovery, deepening our relationships, conflict resolution, decision-making, covisioning, and storytelling. I am looking up through the skylight, and I see the ice-blue pale hue of dawn’s prelude and a single fading star. Gray limbs of the old oak tree curl around the circular window frame to embrace the vision.

I lie still, holding on to what I can from the dream the night before. I wake my friend who lies near me, and we rise and stretch out of our down sleeping bags into the chilly air, with frosty breath and sleepy eyes. We slip into our Uggs while still in our flannels and grab our blankets and pillows. As we open the old creaking wooden door and step into the light, we hear the crows calling. Come, they say. We do. Everything here in the mountains of Ojai is an act of listening, of observing, of being in existence without premeditation or forethought.

We ascend the hillside, where we look over the blanket of fog as it recedes into the valley below. The morning dew is dripping from the branches. We tiptoe into the beautiful circular, wooden-domed Council house, where others waking from their yurts begin to gather. The room is held in by large glass doors, and the arched windows bring a pure rose light of dawn into the space.

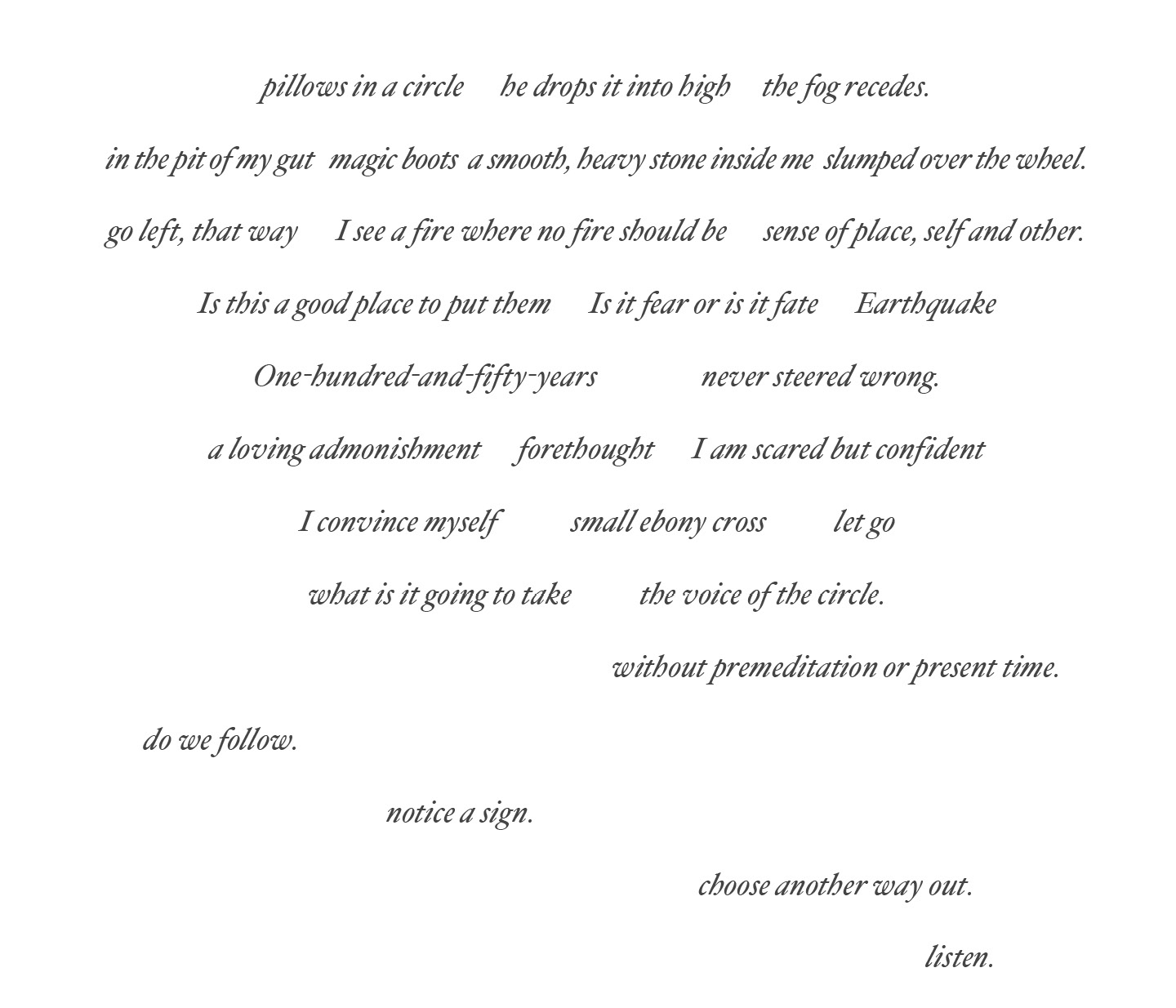

We all lie down on pillows in a circle, face up in our cozy blankets, heads together in the center. We are here for a Dreamstar, a weaving of stories from the shared liminal space between sleeping and waking, a place where we travel together in an imaginal field. The room is still warm from the singing and dancing the night before. Our guide sits on the outside of our circle and invites us into stillness with a deep sonorous strike of the black Ching bowl. I close my eyes and breathe into the vaulted wooden ceiling as I cross the threshold into dreamtime—perhaps a dream from the past, or a reverie in that very moment, or an instance of prescience that may be revealed later as I listen to others.

I float in the field of the room, feel-sensing when to share my vision out loud with my peers, just as they are doing the same. One by one, we speak our stories, always in the voice of present time, listening for when to be silent or when to give voice to the room: attunement. In this space, intuition does not belong to any one person. It belongs to us all, and we are all here in the field together. We cannot see each other’s faces, but we can feel each other’s heat and stirring. As each voice speaks its turn, I wonder, Whose voice is that?... Their story sounds so much like mine.

I wait until I feel a stirring, then I speak.

How do I describe my intuition? As a child, I possessed an inner knowing, and I do not wonder but think that this is just how we all are wired. On a deep level, I understand these are not coincidences. They are readings from our natural collective inner voice. As children, we are closer to our intuition but may not know its name, like the time as a tiny tot I am sleeping next to my great-aunt Jeannette and hear a scurrying on the ceiling above us in the dark. I feel a cold sense in my belly, a knowing. “Scorpion,” I cry out. Aunt Jeannette jumps up and turns on the light, and sure enough, there it is, a big one, coming down the wall toward the bed. Or in 1955 when my distressed mother’s voice rang out in another room while on the telephone, “Oh no, Sally, that’s awful!” Before she could even tell me, I already know. Polio. I am right. Joannie, my childhood friend, has contracted polio.

I listened to that voice again and again as I grew older, and though I did not know at the time, the deep listening I had experienced for many years propelled me into a life-altering event one night in 1974. Overcoming fear, I embraced fate and the field.

It’s a cold winter night in the Eastern High Sierra. The stars are ablaze, and the Milky Way stretches from pole to pole. I am a passenger with my friend, Little John, in his notorious VW Bug. The engine merrily buzzes along California’s Highway 395 as he drops it into high gear, and we scream with delight. I am happy to be back with Johnny, my lifelong friend, who I have spent summers with as a teenage girl, together terrorizing the mountains and valleys of Mono County.

I look southwest across the snow-covered sagebrush flats, up toward Parker Lake and the Mt. Wood bench. I see a fire where no fire should be, an orange blaze emanating through the trees high up on the mountainside. I point it out to Johnny, and we pull off the road to check it out. A strange place for a campfire, it’s about a mile to the base of the mountain and perhaps another half mile up. I feel a cold, smooth stone in the pit of my gut, weighing down inside me. Is it fear, or is it fate? This isn’t just any blaze, it’s a beacon, the stone in my gut tells me. Something’s different. Something doesn’t feel right. Johnny and I lock eyes. We have to go up there and find out.

Johnny is the driver for the town school bus and is used to driving big equipment through any kind of mountain weather, so when he takes off full speed, I know we’re in good hands. He spins off the highway at the next road as we race toward the blaze. We come to a fork in the road. “Which way?” he shouts. The stone inside me rocks, aiming itself toward a direction. “That way,” I say, as I point left. We careen up to the base of the mountain as the road veers south. He cautiously begins approaching the climb in front of us, putting the VW into low gear. We begin the ascent, climbing higher and higher, with the wheels slipping and sliding over the rough, snowy terrain. The Bug starts to drift, and we lose traction. Johnny backs all the way down the road to get a running start, hell-bent on reaching our goal, wheels slipping, snow, mud, and rocks flying as we aim steeper up the mountain.

Through the tall pine trees up ahead, rays of strange light appear, dancing and bobbing erratically through the branches—something different than a fire’s glow. We are about to crest the hill when suddenly a huge vehicle with blinding headlights lurches through the trees, barreling down on us. But for some reason, it doesn’t stop. It continues toward us with no braking in sight. Johnny slams the VW into reverse, trying to back down the hill as the truck grows nearer. On our left, a massive cliff, too steep to veer down. On our right, boulders the size of brownstones. Suddenly the truck veers into an outcropping of piñon pines and comes to a sudden stop, its nose peeking over the edge of the cliff. All is silent, save for the rumbling of the engines.

“Stay in the car,” Johnny whispers.

My heart is in my throat, adrenaline pumping. Johnny grabs a big Maglite and cautiously approaches the cab of the two-ton forestry vehicle. Inside, Johnny finds the driver, slumped over the steering wheel and semiconscious. Johnny signals me to stay put. The man looks up to Johnny, his burned and bloody face smashed in, his wire-rimmed glasses embedded into the bridge of his nose and one of his eyes. He tells Johnny that he works for the US Forest Service, and earlier that day, he was tending to a forestry-ordered slash-and-burn pile. The forestry conducts these slash-and-burns in the winter, making huge piles of deadwood out in open fields, surrounded by snow so that they don’t set the rest of the woods on fire. A blazing timber had rolled off the top of one of the fires and smashed the man in the face. Johnny immediately goes into triage. He sloshes back down to me in the ruts of the snow and ice. He is breathing heavily and tells me that the driver of the truck is severely wounded and that I will have to back the Bug down the hill so he can drive the wounded forester to the emergency center in town.

I am scared but confident as I drive backward down the dangerous, precipitous hill, in the night, in the dark, in the snow and ice, ten miles from civilization. I am afraid, but I tell myself I will make it. The wheels slip and slide backward underneath me until I can pull over at the bottom of the grade so Johnny can pass. The sleet and snow flies off the back wheels as I follow the lumber truck back into town to the small emergency facility. Feeling urgency and hope at the same time, I breathe easier now, the weight inside lifting.

We could have just ignored the blaze as we drove down that highway, shrugged it off. If I had shown hesitation or fear and not listened to the cry for help I was feeling from the field, Johnny and I would not have gone on that wild adventure and possibly saved that forester’s life.

With life’s hurried pace, I have frequently not listened to that voice. In those moments, I am disconnected from the origins of my nature—listening, watching, feeling—what we now call mindfulness. We have a natural interior rhythm that can connect with the larger collective consciousness, if we choose to use it. Thinking more with our instinctive center, our hearts, rather than our brains, we can receive the natural information we need. When I fret and think too much with my brain instead of my body—when I don’t slow down to attune—that’s when bad things can happen.

It’s 2005. My husband, Russ, has received several beautiful, illuminated awards from the county and city of Los Angeles for his work as a celebrated actor in film and as a native of the city. I am in the never-ending process of shifting things around to organize what I call like with like, which means putting all things alike together in one place. I am in our old 1920s garage that serves as an art studio and storage for all of our family memorabilia. There is a sturdy filing cabinet with drawers that slide as slick as ice. Is this a good place to put them? I ask myself.

Will I listen to the answer, or will I ignore it?

The awards are in beautiful portfolio binders and are too large to fit inside the cabinet; I’ll just put them on top instead. I look up at the stucco ceiling just above the cabinet. Strange. (Why did I look up?) Water stains are on the ceiling. I hesitate. The stone anchors inside me. We’ve used this space for thirty years, and it’s never leaked, I convince myself. These are just old stains from long ago. Besides, the landlord just put a new surface on the deck above us. Furthermore, I am too busy to listen to my fears. Satisfied, I put the awards on top of the cabinet and leave.

I return a few days later to find all the memorabilia soaked. The apartment upstairs had a leak under the sink, and as water will do, it found its way into the exact spot I had scoped out. The folders are soggy and the precious certificates blurred around the edges.

I shake my head and scold myself, I told you, I told you! When will you listen?

In 2012, I’m preparing to meet my daughter Amber in Virginia for a show where we are performing music and poetry together, after which I’ll head to San Francisco to celebrate the release of my album with my record label, Light Rail Records. I’m in a mad flurry of preparation, checking off a list of everything I need to bring. My guitar for the shows, check. Set list, check. Boarding pass and travel information, check. My special magic boots I wear for performances, check. I rush to the laundry room to finish the last bits of laundry and notice a sign on the telephone pole outside.

Guard Your Possessions

Many Recent Burglaries In This Neighborhood

I tell Russ about the sign, and he says, “Maybe you should put your family heirlooms in our hiding place,” a secret compartment he built in our house. I figure the locked drawer in our bedroom is good enough—burglaries usually only happen when opportunities present themselves.

Are you sure? The stone inside me heaves. I’m sure.

I move on, but the warning signs keep coming. I accidentally leave my magic boots at the hotel in Virginia, and they are never found. Other things disappear. By the time I get to San Francisco, where I meet up with Russ, we wake to an earthquake and then a phone call from our neighbor. Someone has broken into our apartment through a window on the alley side of the building—poor Russ forgot to lock it. The bad news comes tumbling out of the phone as Russ and I ask our neighbor to check for the jewelry: it’s gone. The locked box is battered and broken open. Five generations, one-hundred-and-fifty-years’ worth of precious family history is removed from my life and my grandchildren’s future, forever. We leave San Francisco and head home, no celebration of my album, only devastation.

What is it going to take, I ask myself, for me to learn how to listen, from the outside in?

The robbers are eventually found by a detective using fingerprints obtained from the windowsill where they entered. Just some dumb kids doing petty crime, with no clue as to the significance of what they’ve stolen from my family. At one of the kid’s homes, a piece of jewelry is identified as mine: a small black ebony cross outlined in gold that belonged to my great-great-grandmother Alice, the wife of Colonel John Jay Young, my great-great-grandfather who fought on the side of the Union in the Civil War. She would hold that cross and pray for his safe return every day, and one day he finally did come home.

In 1980, when my mother was on her deathbed, throwing her last punch in a long, brutal fight against ovarian cancer, I placed that cross in her hand and prayed so hard for her ancestors to come bring her home. As if she knew the cross was there, her frail fingers closed to hold it, and she let go of her life in the same moment.

It is the only piece of the stolen heirlooms that is rescued that day from the thief’s house, and it just so happens to be one of the most valuable to me, personally. I am stunned when the detective has me identify it—I am speechless, suddenly overjoyed, still in my deep sadness. Why was this one piece the only one that was returned to me and not any of the others? It is an affirmation that the ancestors are also in the field, that what once was still is, that every heartbreaking experience holds a lesson about listening to our intuition, if we will allow ourselves to.

Another memory of the Upper Ojai Valley comes to me. It’s 2015 and the morning after a monstrous storm. I’m on the land facilitating Council with high school seniors for a Senior Rites of Passage retreat, a tradition for teenagers to transition into another chapter and year of their lives. Right now, they are wandering in the wilderness, enjoying the gifts of nature as their teacher. Most of these students have been in the practice of Council throughout their school years, a practice where we sit in a circle facing one another and listen and speak from our hearts without fear of judgment or opinion. Opinion and judgment are merely stories that have lost their narrative. Perhaps you remember a time set aside in kindergarten where you had show-and-tell in a circle on the floor, each child having the opportunity to share as the others are invited to listen. Simply, when it is your turn to speak, we listen to you—something five-year-olds can often do better than grown-ups! We gain wisdom from the gifts of many and connect to the Voice of the Circle, the one that speaks for us all. Learning these tools has brought me into authenticity with all beings. It’s a generous way to live, to listen deeply without the interjection of our thoughts, without planning what you are going to say, and then to speak from that place of intuition, in that moment.

The sun is starting to set. The students have had their time with nature. The bell is rung, and it beckons the students back to the beautiful Council house to take their seats in circle. There is one student who we will call Coyote because of his wandering curiosity and divergent participation. We wait and wait, and he is late. The land is particularly rugged and dangerous today because of the heavy rains the night before. The group leader says we will wait till he gets here.

No, the voice inside me speaks. Go find him. This time, I listen and follow.

I excuse myself, not to draw attention, and I leave. I am walking down the path, past the entrance archway by an old toyon tree burned by a fire from years ago. It is black and gnarled, with a large heavy limb arched close to the path. With no particular sense of direction, I wander until I find Coyote coming up the road ahead. I signal to him to hurry, and he quickens his pace. He apologizes; he did not hear the bell. I give a loving admonishment that it is all in good time. We pass back under the toyon tree, and I tell him the story of the fire that swept through this land years ago. We stand and take note, honor the blackened limbs that were allowed to remain. Then we return to the Council house and take our seats.

Shortly after, the land steward comes into the room with a warning: she tells us the massive toyon tree has collapsed, its heavy trunk shattering across the path where the student and I had just been walking. She says to avoid that area, to choose another way out.

Ding. The bell rings again, the warning is received but so is the lesson.

When I don’t listen to my intuition, to the field, the outcome reflects a silencing of myself, a conclusion I very likely could have helped alter, had I followed through, like Russ’s memorabilia on the cabinet, my family heirlooms. But when I do listen to that voice inside me, that pulling stone in my gut which tells me to heed caution or take action—the scorpion climbing down the wall, the High Sierra mountain with Little John, Coyote under the toyon tree—I am almost never steered wrong. And if there is mystery in the telling of these stories, children, that is because much of how intuition reveals itself is exactly like that: just when we are not looking for it, there it is, revealed in the listening, in the quiet space between.

Back to the beginning of the story, to the Dreamstar in 2017, in the Council house, our heads together in the circle.

We share our reveries and visions for a good while until there is silence and a feeling of completion. The sun crests the hill to spill golden warmth into the room. Our guide once again rings the black Ching bowl. He invites us to speak into the center and to witness what we have heard from each other during this collective dreamtime. Then, still on our backs, we weave out loud and we witness back to one another the vivid phrases and words we have heard spoken in the room. The spirit of our stories, commonalities, landscapes, colors, rhythms, and the patterns of our human existence—from the deepest listening—spirals round our center. The room is full of sun now, and we turn over to face one another, beaming brightly, seeing our eyes full of wonder for the first time.

We are all deeply interwoven, to each other, and to ourselves. All we have to do is hear what was always there, always guiding us from within.