Most of what we know about ancient life was learned from studying fossils. A fossil forms when the tissues of a once-living organism, whether a plant or an animal, are replaced with minerals. Usually, this occurs when the organism is buried or sinks in an environment with little oxygen, which slows down decomposition. If buried completely, the tissue may never fully decompose, leaving it trapped in sediment. As the sediment turns to rock, dissolved minerals can penetrate and replace the organic material with calcite, quartz, or other minerals. In other cases, carbon released from the organic matter, in the form of carbon dioxide, reacts with minerals in the surrounding rock, such as iron, and replaces the organic matter with minerals that the decomposing body helped to create. In either case, the mineralized material perfectly preserves the animals and plants in which it formed, and the fossil’s “new” material is often quite sturdy, enabling it to endure eons within rock.

In the case of corals, however, much of the “work” of fossilization is already completed while the colony is still alive. Because corals already create hard, mineralized skeleton structures themselves, corals don’t need mineral replacement to be preserved. Instead, since coral reefs naturally grow upward upon older reef material below, coral can become a fossil simply by remaining intact long enough for other sediment to fill in around it. Eventually, the buried parts of the reef turn into limestone, a type of sedimentary rock that consists entirely of fossilized marine organisms.

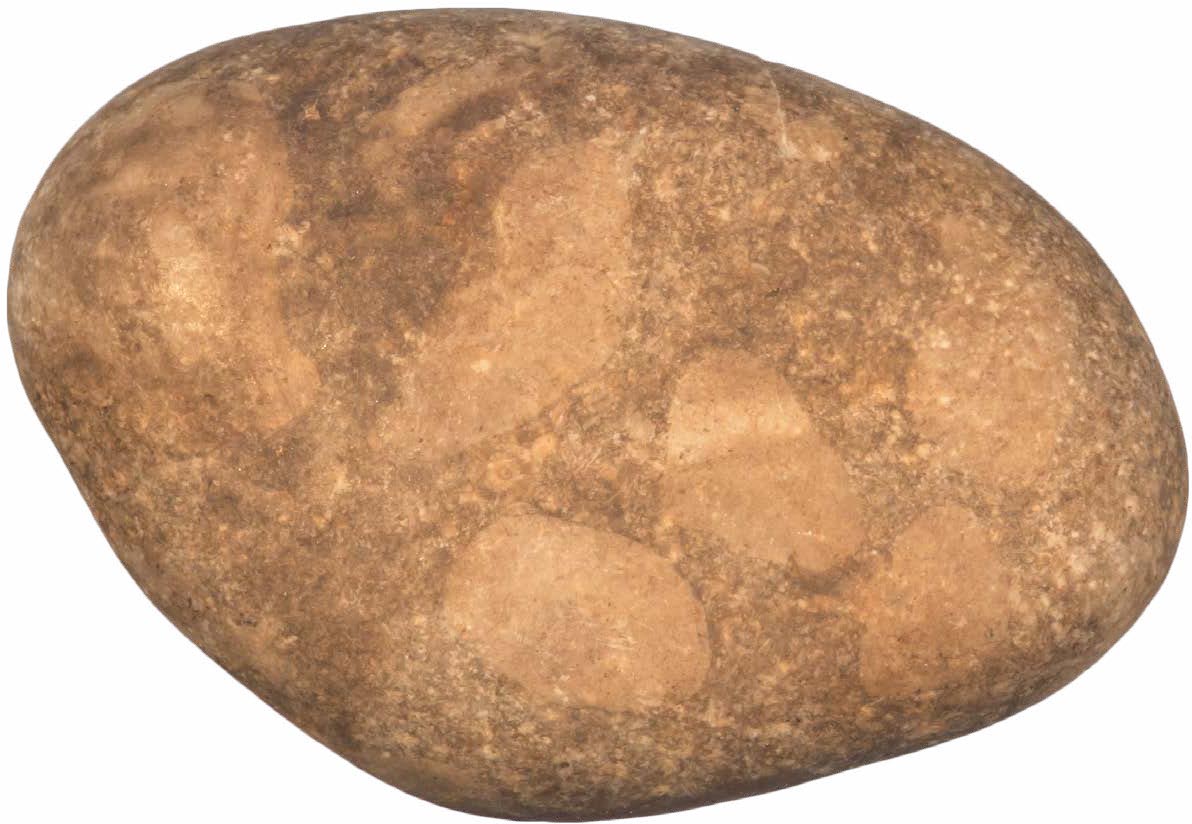

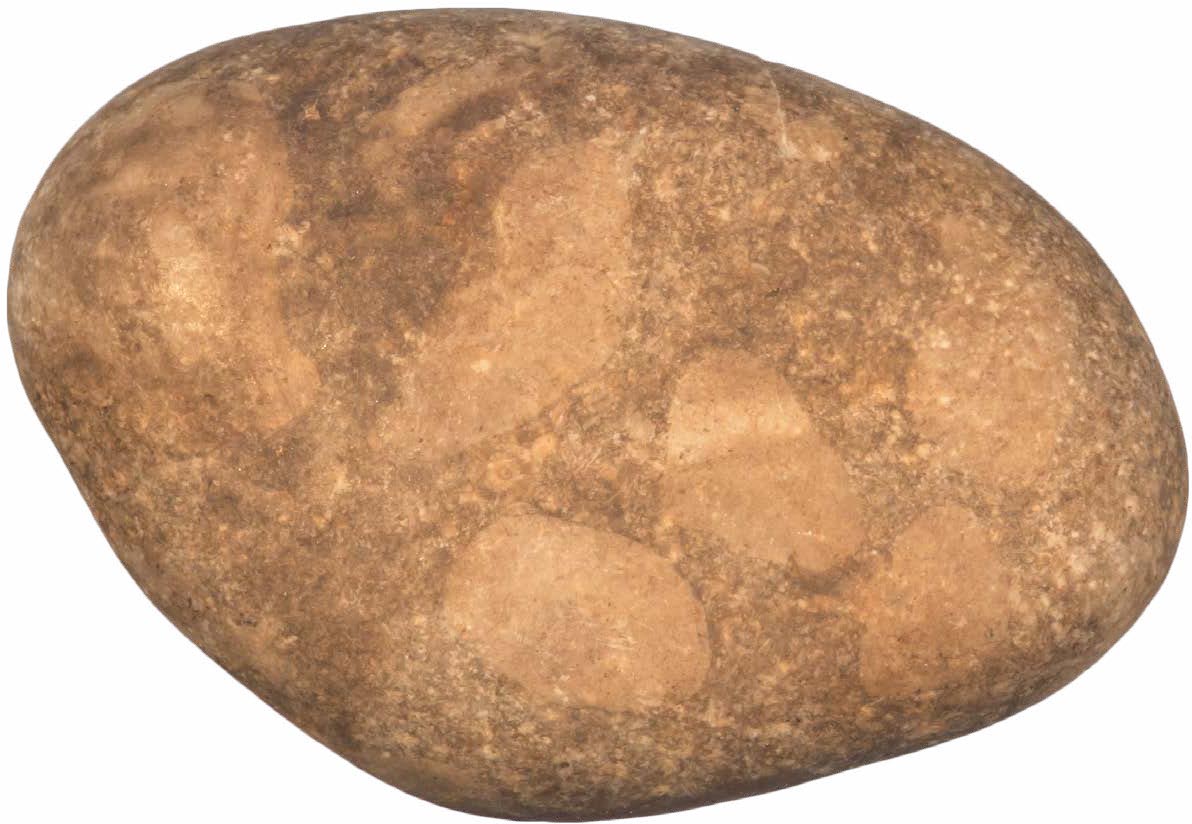

This fragmented mass of limestone, found in Charlevoix alongside Petoskey stones, contains traces of fossil matter but no well-developed coral.

Fossilization can preserve surprisingly fine structures, such as the gauze-like texture of this horn coral.

Well-fossilized Petoskey stone will show details that reveal the true structure of the coral that formed it.

In some specimens of Petoskey stone, softer areas have dissolved or are otherwise absent, making for a particularly skeletal appearance.