We sociolinguists often find ourselves discussing changes that are taking place in the speech communities around us. The changes themselves are usually crystal clear – for example, dived is being replaced as the past-tense form by dove, as in the case study I discuss below. And the way those changes are being realized – actualized, we usually say – in the speech of the community is also quite clear in most cases. Using methods that are by now well tested, we can discover the frequency of innovative forms like dove in the speech of twenty-year-olds and contrast that with its frequency in the speech of fifty-year-olds or eighty-year-olds, as I also do in the case study below. We can compare women with men, or people from different neighborhoods, or people of different social and occupational status, sifting through the evidence until we are confident we know who is leading the change and where it is heading.

But it is often much more difficult for us to pinpoint the reasons for the change – its motivation. The reasons behind linguistic changes are almost always very subtle. The number of possibilities is enormous, taking in such factors as motor economy in the physiology of pronunciation, adolescent rebellion from childhood norms, grammatical finetuning by young adults making their way in the marketplace, fads, fancies and fashions, and much more. All these things operate beneath consciousness, of course, making their detection even harder. You can’t see them or measure them; you can only infer them.

Besides that, linguistic change is mysterious at its core. Why should languages change at all? From the beginning of recorded history (and presumably before that), people have been replacing perfectly serviceable norms in their speech with new ones. Why not keep the old, familiar norms? No one knows. All we know for certain is that language change is as inevitable as the tides.

So, very often we are forced to admit that the motivation for a change is unclear, or uncertain, or undetectable. We can often point to trends – sometimes even to age-old tendencies (again, as in the change of dived to dove below) that suddenly accelerated and became the new norm. But exactly why that tendency toward change arose and, more baffling, exactly why it accelerated at that time and in that place is a very difficult question, one of the most resistant mysteries of linguistics.

Knowing all this, we are perpetually surprised to find that very often the people we are discussing these linguistic changes with – our students, colleagues in other departments, audiences at lectures, newspaper reporters, dinner-party guests – know exactly why the changes are taking place. It’s because of television, they say. It’s the mass media – the movies and the radio, but especially the television.

Television is the primary hypothesis for the motivation of any sound change for everyone, it seems, except the sociolinguists studying it. The sociolinguists see some evidence for the mass media playing a role in the spread of vocabulary items. But at the deeper reaches of language change – sound changes and grammatical changes – the media have no significant effect at all.

The sociolinguistic evidence runs contrary to the deep-seated popular conviction that the mass media influence language profoundly. The idea that people in isolated places learn to speak standard English from hearing it in the media turns up, for instance, as a presupposition in this passage from a 1966 novel by Harold Horwood set in a Newfoundland fishing outport:

The people of Caplin Bight, when addressing a stranger from the mainland, could use almost accentless English, learned from listening to the radio, but in conversation among themselves there lingered the broad twang of ancient British dialects that the fishermen of Devon and Cornwall and the Isle of Guernsey had brought to the coast three or four centuries before.

The novelist’s claim that the villagers could speak urban, inland middle-class English – presumably that is what he means by ‘almost accentless English’ – from hearing it on the radio is pure fantasy. It is linguistic science-fiction.

A more subtle fictional example, this one set in the apple-growing Annapolis Valley in Nova Scotia, will prove more instructive for us in trying to get to the roots of the myth. In a 1952 novel by Ernest Buckler, The Mountain and the Valley, the young narrator observes certain changes in his rural neighbors. His description of those changes is characteristically grandiloquent:

And the people lost their wholeness, the valid stamp of their indigenousness… In their speech (freckled with current phrases of jocularity copied from the radio), and finally in themselves, they became dilute.

Here, the author does not claim that the mass media are directly responsible for the dilution of regional speech. He does, however, conjoin the two notions. The dialect is losing its local ‘stamp’, he says, and incidentally it is ‘freckled’ with catch-phrases from the network sitcoms.

Beyond a doubt, mass communication diffuses catch-phrases. At the furthest reaches of the broadcast beam one hears echoes of Sylvester the Cat’s ‘Sufferin’ succotash’, or Monty Python’s ‘upper-class twit’, or Fred Flintstone’s ‘Ya-ba da-ba doo’. When an adolescent says something that his friends consider unusually intelligent, the friends might look at one another and say, ‘Check out the brains on Brett’ – although the speaker is not named Brett. That line is a verbatim quotation from the 1994 film Pulp Fiction. Or they might compliment someone and then take it back emphatically: ‘Those are nice mauve socks you’re wearing – NOT!’ That phrase originated on an American television program, Saturday Night Live, in 1978, but it went almost unnoticed until it came into frequent use in one recurring segment of the same show twelve years later. From there, it disseminated far and wide in a juvenile movie spin-off called Wayne’s World in 1992. Once it gained world-wide currency, other media picked it up, charting its source and tracking its course and spreading it even further. But its very trendiness doomed it. It was over-used, and a couple of years later it was a fading relic.

Such catch-phrases are more ephemeral than slang, and more self-conscious than etiquette. They belong for the moment of their currency to the most superficial linguistic level.

Unlike sound changes and grammatical changes, these lexical changes based on the media are akin to affectations. People notice them when others use them, and they know their source. And they apparently take them as prototypes for other changes in language. If the mass media can popularize words and expressions, the reasoning goes, then presumably they can also spread other kinds of linguistic changes.

It comes as a great surprise, then, to discover that there is no evidence for television or the other popular media disseminating or influencing sound changes or grammatical innovations. The evidence against it, to be sure, is indirect. Mostly it consists of a lack of evidence where we would expect to find strong positive effects.

For one thing, we know that regional dialects continue to diverge from standard dialects despite the exposure of speakers of those dialects to television, radio, movies and other media. The best-studied dialect divergence is occurring in American inner cities, where the dialects of the most segregated African-Americans sound less like their white counterparts with respect to certain features now than they did two or three generations ago. Yet these groups are avid consumers of mass media. William Labov observes that in inner-city Philadelphia the ‘dialect is drifting further away’ from other dialects despite 4–8 hours daily exposure to standard English on television and in schools.

For another thing, we have abundant evidence that mass media cannot provide the stimulus for language acquisition. Hearing children of deaf parents cannot acquire language from exposure to radio or television. Case studies now go back more than twenty-five years, when the psycholinguist Ervin-Tripp studied children who failed to begin speaking until they were spoken to in common, mundane situations by other human beings. More recently, Todd and Aitchison charted the progress of a boy named Vincent, born of deaf parents who communicated with him by signing, at which he was fully competent from infancy. His parents also encouraged him to watch television regularly, expecting it to provide a model for the speech skills they did not have. But Vincent remained speechless. By the time he was exposed to normal spoken intercourse at age three, his speaking ability was undeveloped and his capacity for acquiring speech was seriously impaired. He had not even gained passive skills from all the televised talk he had heard.

Finally, the third kind of evidence against media influence on language change comes from instances of global language changes. One of the best-studied global changes is the intonation pattern called uptalk or high rising terminals, in which declarative statements occur with yes/no question intonation. This feature occurs mainly (but not exclusively) in the speech of people under forty; it is clearly an innovation of the present generation. Astoundingly, in the few decades of its existence it has spread to virtually all English-speaking communities in the world; it has been studied in Australia, Canada, England, New Zealand and the United States. Its pragmatics are clear: it is used when the speaker is establishing common ground with the listener as the basis for the conversation (Hello. I’m a student in your phonetics tutorial?), and when the speaker is seeking silent affirmation of some factor that would otherwise require explanation before the conversation could continue (Our high-school class is doing an experiment on photosynthesis?). Its uses have generalized to take in situations where the pragmatics are not quite so clear (as in Hello. My name is Robin?).

So we know how it is used, but we do not know why it came into being or how it spread so far. Many people automatically assume that a change like this could never be so far-reaching unless it were abetted by the equally far-reaching media. But nothing could be further from the truth. In fact, the one social context where uptalk is almost never heard is in broadcast language. To date, uptalk is not a feature of any newsreader or weather analyst’s speech on any national network anywhere in the world. More important, it is also not a regular, natural (unselfconscious) feature of any character’s speech in sitcoms, soap operas, serials or interview shows anywhere in the world. Undoubtedly it soon will be, but that will only happen when television catches up with language change. Not vice versa.

Another telling instance comes from southern Ontario, the most populous part of Canada, where numerous changes are taking place in standard Canadian English and many of them are in the direction of north-eastern American English as spoken just across the Niagara gorge. The assumption of media influence is perhaps to be expected because of the proximity of the border on three sides and also because American television has blanketed Ontario since 1950. But closer inspection shows the assumption is wrong.

One example of the changes is dove, as in The loon dove to the floor of the lake. The standard past tense was dived, the weak (or regular) form. Indeed, dived was the traditional form, used for centuries. But in Canada (and elsewhere, as we shall see) dove competed with it in general use in the first half of this century, and now has all but replaced it completely.

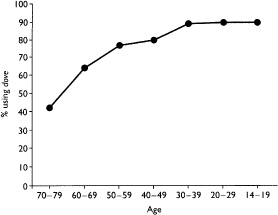

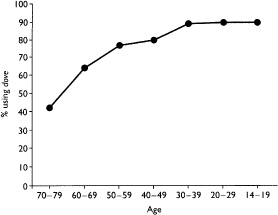

The progress of this grammatical change is graphically evident in Figure 1, which shows the usage of people over seventy at the left-hand end and compares it with younger people decade by decade all the way down to teenagers (14–19) at the right-hand end. These results come from a survey of almost a thousand Canadians in 1992. People born in the 1920s and 1930s – the sixty- and seventy-year-olds in the figure – usually said dived, but people born in succeeding decades increasingly said dove. Since the 1960s, when the thirty-year-olds were born, about 90 per cent say dove, to the point where some teenagers today have never heard dived and consider it ‘baby talk’ when it is drawn to their attention.

The newer form, dove, is unmistakably American. More than 95 per cent of the Americans surveyed at the Niagara border say dove. In fact, dove has long been recognized by dialectologists as a characteristically Northern US form. In Canada, it had been a minority form since at least 1857, when a Methodist minister published a complaint about its use in what he called ‘vulgar’ speech.

Is the Canadian change a result of television saturation from America? Hardly. The past tense of the verb dive is not a frequently used word, and so the possibility of Canadians hearing it once in American broadcasts is very slim, let alone hearing it so frequently as to become habituated to it. More important, there is evidence that dove is replacing dived in many other places besides Canada. For example, students in Texas now use dove almost exclusively, whereas few of their parents and none of their grandparents used this (formerly) Northern form.

Figure 1: Percentage of Canadians who use dove rather than dived

The fact that these language changes are spreading at the same historical moment as the globalization of mass media should not be construed as cause and effect. It maybe that the media diffuse tolerance toward other accents and dialects. The fact that standard speech reaches dialect enclaves from the mouths of anchorpersons, sitcom protagonists, color commentators and other admired people presumably adds a patina of respectability to any regional changes that are standardizing. But the changes themselves must be conveyed in face-to-face interactions among peers.

One of the modern changes of even greater social significance than the media explosion is high mobility. Nowadays, more people meet face to face across greater distances than ever before. The talking heads on our mass media sometimes catch our attention but they never engage us in dialogue. Travelers, salesmen, neighbors and work-mates from distant places speak to us and we hear not only what they say but how they say it. We may unconsciously borrow some features of their speech and they may borrow some of ours. That is quite normal. But it takes real people to make an impression. For us no less than for Vincent.

I previously discussed the influence of mass media and other postmodern factors on language change in ‘Sociolinguistic dialectology’ (in American Dialect Research, Dennis Preston (ed.), Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 1993, especially pp. 137–42). Detailed explanations of the social motivations for linguistic change may be found in my book Sociolinguistic Theory: Linguistic variation and its social significance (Oxford: Blackwell, 1995, especially Chs. 2 and 4).

The two novels cited are Tomorrow will he Sunday, Harold Horwood (Toronto: Paperjacks, 1966) and The Mountain and the Valley, Ernest Buckler (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1961).

William Labov’s observation of dialect divergence despite intensive media exposure comes from his presentation on ‘The transmission of linguistic traits across and within communities’, at the 1984 Symposium on Language Transmission and Change, Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences.

Case studies of the hearing children of deaf parents may be found in Susan Ervin-Tripp, ‘Some strategies for the first two years’ (in Cognition and the Acquisition of Language, New York: Academic Press, 1973, pp. 261–86) and ‘Learning language the hard way’, by P. Todd and J. Aitchison in the journal First Language 1 (1980), pp. 122–40. The case of Vincent is also summarized in Aitchison’s book, The Seeds of Speech (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996, pp. 116–17).

Some studies of uptalk or high rising terminals include ‘An intonation change in progress in Australian English’ by Gregory Guy et al., in Language in Society 15 (1986), pp. 23–52, ‘Linguistic change and intonation: the use of high rising terminals in New Zealand English’ by David Britain, in Language Variation and Change 4 (1992), pp. 77–104 and ‘The interpretation of the high-rise question contour in English’ by Julia Hirschberg and Gregory Ward, in Journal of Pragmatics 24 (1995), pp. 407–12.

My study of dove replacing dived is reported with several other current changes in ‘Sociolinguistic coherence of changes in a standard dialect’, in Papers from NWAVE XXV (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1996). The study of dived and dove in Texas is by Cynthia Bernstein in ‘Drug usage among high-school students in Silsbee, Texas’ (in Centennial Usage Studies, G. D. Little and M. Montgomery (ed.), Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1994, pp. 138–43).