2

GERM DETECTIVE

“One very disagreeable fact about typhoid fever is that it is intimately associated with human excrements.” —William Sedgwick

Deadly diseases had affected George Soper’s life from its beginning in 1870. Two months before George was born in Brooklyn, New York, his father died of tuberculosis, leaving a pregnant widow and two-year-old daughter.

When George was twelve, the German scientist Robert Koch announced his discovery of the tuberculosis bacterium, the microbe that had killed Mr. Soper and millions more. The medical community began to understand that other diseases, including typhoid fever, were also caused by germs that could be transmitted between people.

Lethal microbes had plenty of opportunity to spread as the population of the United States exploded. By the time George Soper turned thirty, he had seen the nation’s size double to 76 million as immigrants flooded in. Many of the newcomers settled in the fast-growing cities. In 1870, only 25 percent of the American population lived in urban areas. By 1900, that number had increased to 40 percent.

Crowded cities, like New York where George grew up, were grimy, stinking, unsanitary places. Raw sewage fouled the water. Mountains of spoiled food and garbage lined the sidewalks, rotting in the sun. Horses dropped 2,000 tons of manure on streets every day. The city was littered with dead and decomposing animals, including cattle, donkeys, dogs, rats, and more than 10,000 horses a year. Too many people lived crammed together in filthy, poorly built tenement buildings that had overflowing outhouses.

This environment was hard on the body. A white male born in a major American city was likely to die ten years sooner than one born in a rural area.

GERM FIGHTING

Doctors, scientists, and public health officials realized that by controlling or eliminating germs, they could prevent some of the deadly diseases. Engineers went to work designing ways to improve dirty living conditions.

George Soper wanted to be part of the sanitation movement, and a career in engineering was a way to do that. He studied for his bachelor’s degree in engineering at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, New York, located along the Hudson River north of New York City.

As a student, George joined the battle against infectious diseases. While spending one Christmas vacation in New York State’s Adirondack Mountains, he heard about two typhoid fever patients living nearby. Their rented house had a history of harboring typhoid and other contagious diseases. George decided that the building was too unsanitary to be safe, and he helped the two patients and their families move out. Then he convinced the house’s owner that the best way to deal with such a cursed place was to destroy it. With the owner’s permission, George burned it down.

After Soper received his degree, he worked as a civil engineer for the Boston Waterworks and for a company that built systems to filter drinking water. Later, he returned to New York City and enrolled at Columbia University where, in 1899, he earned his Ph.D. in engineering.

Armed with this training, Soper set up a consulting business on Broadway in Lower Manhattan. He advertised himself as a “Sanitary Engineer and Chemist.” Communities throughout the country hired him to study their sanitation systems, find the defects, and suggest ways to fix them. Soper became known as a “germ detective.”

FECES, FINGERS, AND FLIES

It was Soper’s business to know everything about typhoid fever—what caused it, how it spread, and how to stop it.

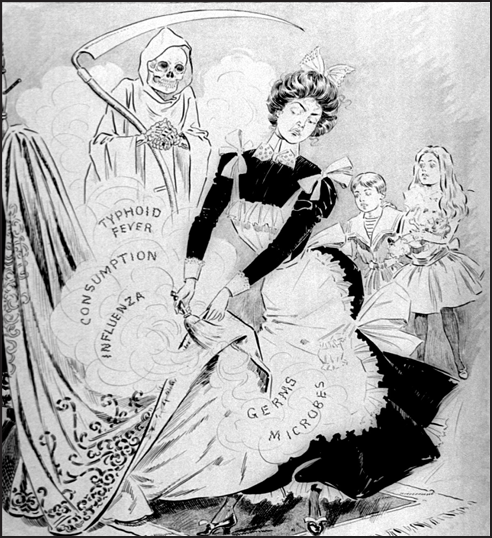

Typhoid was among the top five fatal infectious diseases in the United States, along with influenza, pneumonia, tuberculosis, and diphtheria. In 1900, it struck nearly 400,000 Americans, and more than 35,000 of them died.

Only humans catch typhoid fever. Only humans pass it to others. The typhoid bacterium doesn’t need an intermediary host like a mosquito, which carries malaria and yellow fever from human to human when it bites them.

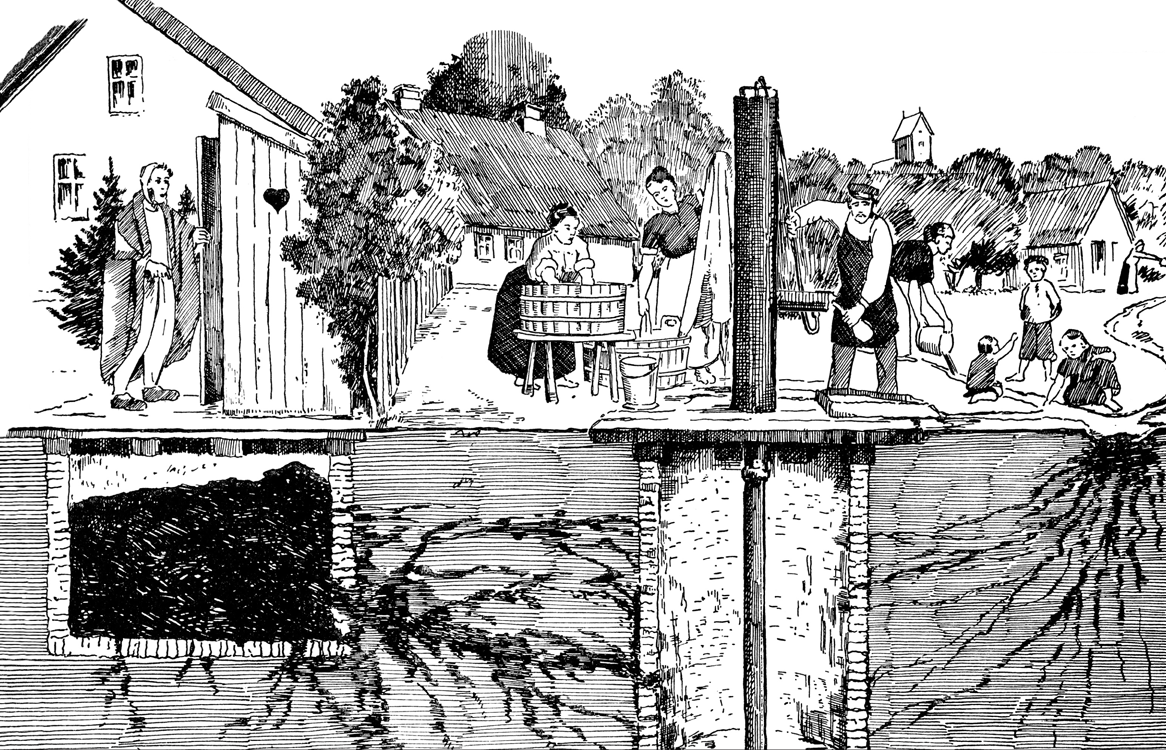

Instead, the germ travels from the feces and urine of one person to the mouth of another, usually by way of water or food. Under the right conditions, it can survive several weeks in water and soil.

George Soper had seen what happened when typhoid germs infected someone. The victim started to feel sick between one to three weeks after ingesting the bacteria. Maybe he drank river water contaminated with sewage from the town upstream. Or perhaps she ate a salad doused with well water polluted by oozing waste from an outhouse. Or he swallowed raw shellfish taken from a bay where sewage was dumped. Maybe it was the unpasteurized milk that had been poured into a milk pail recently rinsed out with bacteria-laden water.

Cooking killed typhoid germs, but food could still be contaminated before it was eaten. A person touched it with unwashed fingers carrying bits of feces. A fly landed, its legs transporting human waste from a recent visit to an unscreened outhouse. If food sat too long at room temperature, these bacteria multiplied, creating even more dangerous germs.

In the early twentieth century, doctors referred to typhoid as a disease caused by the four Fs: feces, food, fingers, and flies. Dr. William Sedgwick, a Massachusetts scientist and epidemiologist, observed: “Dirt, diarrhea and dinner too often get sadly confused.”

GHASTLY SYMPTOMS

The typhoid victim probably had forgotten, or never knew, when he was infected with the bacteria. But now he had a headache, felt tired and weak, and had lost his appetite. As the disease progressed, his temperature rose as high as 104 degrees and he no longer had the energy to get out of bed. Other symptoms appeared, including abdominal pain, constipation, chills, and red spots on the chest and abdomen.

The illness typically lasted three to four weeks. Some people had mild cases with few symptoms, barely realizing they were sick. Others struggled for months to recover. In the most severe cases, patients became delirious, developed diarrhea, and bled profusely from the intestines. They grew weaker until they died, often in agonizing pain.

For about 10 to 30 percent of typhoid patients, the disease was fatal. No one was sure why people reacted so differently. Doctors guessed that it depended on the amount of bacteria victims ingested, the strength of their immune systems, and the quality of the nursing care they received.

In the early 1900s, the basic treatment was to keep patients comfortable in bed, using sponge baths to lower body temperature. No medicine or tonic would kill the bacteria as they multiplied and damaged the body. No surgical procedure could remove the microorganisms. Typhoid fever had to run its course until the victim’s immune system defeated it or he died. Those who survived usually were protected from future attacks.

KEEP OUT THE SEWAGE

George Soper was aware that the “discharges from a single patient [had] been known to pollute the entire water supply of a city sufficiently to cause a serious epidemic of typhoid fever.” All it took to infect someone was “less than one glass of water containing typhoid bacilli.”

The way to protect the public was to stop sewage from entering water sources—streams, rivers, lakes, and wells—and to purify contaminated drinking water. Engineers like Soper were confident that if those changes happened, typhoid epidemics would end. London, Paris, and Berlin had already seen far fewer outbreaks as a result of their efforts to keep water supplies free of sewage.

The United States lagged behind Europe, but it was improving. During Soper’s childhood in the early 1880s, nearly 1 in 5 Americans could expect to get typhoid during his or her lifetime. By the beginning of the twentieth century, better sanitation had brought that rate down to about 1 in 10.

Still, in 1900, thousands of New York City’s 3.5 million residents caught the disease. More than 700 died, a typhoid death rate almost four times that of Berlin, Germany.

In the city of Troy, New York, where Soper had gone to college, typhoid’s fatality rate during the same year was seven times higher than New York City’s. In one outbreak, hundreds of Troy’s 60,000 inhabitants were infected, and 93 died.

Towns and rural areas, where the majority of Americans lived in 1900, didn’t escape. Typhoid broke out when waste from outhouses leaked into wells and surface water. The press paid less attention to these epidemics because fewer people became ill than in a large city. Yet the impact on a community was devastating.

During the winter of 1903, typhoid fever invaded Ithaca, New York, two hundred miles northwest of New York City. The disease spread among not only the 13,000 townspeople but also the 3,000 Cornell University students. As the epidemic grew, so did fear and panic.

Germ detective George Soper would find himself at the center of this frightening outbreak.

Typhoid Fever

Typhoid fever has plagued humans since prehistoric times. Genetic research suggests that the bacteria might have been around for twenty thousand years, even before humans settled into villages and developed agriculture.

Typhoid wasn’t recognized as a separate disease until the late 1830s. Before that, doctors confused it with typhus, which is caused by a microbe spread by lice, fleas, mites, and ticks. Typhoid got its name because its symptoms—high fever and rash—resembled those of typhus. Both names come from the Greek word for foggy or hazy, which refers to a feverish patient’s mental condition.

Doctors once thought that typhoid fever, like many diseases, was caused by a miasma, air poisoned by decaying organic material. This idea seemed reasonable since sicknesses were often linked to smelly sewer gases, swampy ground, stagnant water, and decomposing animals and plants.

Then during the 1840s, British physician William Budd (1811–1880) began a study of typhoid fever after he almost died of it. He discovered a connection between the outbreak of new cases and water contaminated with the feces of typhoid patients. In 1856, Budd advised fellow physicians that the disease’s spread could be prevented by boiling drinking water and by chemically disinfecting typhoid patients’ excrement and soiled linens.

No one realized then that microorganisms caused diseases. This idea, called the germ theory, took hold in the medical community during the 1880s and 1890s, thanks to research by Louis Pasteur (1822–1895), Robert Koch (1843–1910), and others. In 1880, Karl Eberth (1835–1926), a German microbiologist, identified a bacterium found in typhoid patients as the microbe behind the disease. Today it is known as Salmonella Typhi.The bacterium is related to other types of Salmonella that cause food poisoning symptoms such as diarrhea and vomiting. But their effects are milder than Salmonella Typhi’s and usually not fatal.

A typhoid fever victim can give off a trillion of the bacteria in each gram of his or her feces (about the weight of a paper clip). A small fraction of that is enough to produce infection in someone who swallows them.

The bacteria travel to this person’s stomach, where acid kills some. The rest enter the small intestine, where they invade the intestinal lining and cross into the bloodstream.

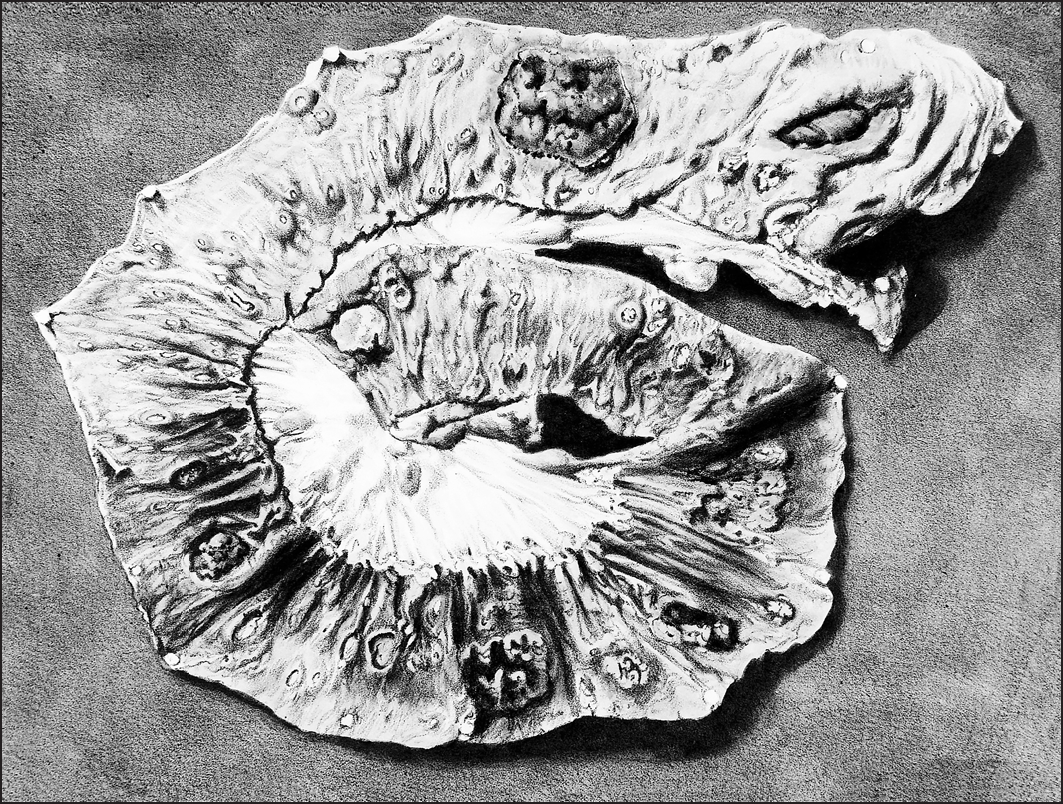

As these bacteria multiply and spread, they may cause infections throughout the body, including in the liver, gallbladder, spleen, bone marrow, lungs, heart, and kidneys. The bacteria do their deadliest damage in the intestines. They may trigger profuse bleeding or create holes that allow the contents of the intestine to escape into the abdominal cavity. This can lead to a slow, painful death and is the major cause of typhoid fatalities.

Typhoid fever’s early symptoms resemble other illnesses, making it hard to diagnose. In 1903, it was often confused with influenza, called grippe. At that time, the preferred—though not foolproof—way to confirm typhoid was the Widal blood test.

Developed in 1896 by French physician Georges Widal (1862–1929), the method uses a few drops of the patient’s blood mixed with a specially grown culture of typhoid bacteria. If the person has typhoid fever, his blood contains antibodies against the bacteria. These antibodies react with the bacteria in the culture, causing them to clump. The Widal test isn’t accurate until the patient has been sick for several days and has built up sufficient antibodies.

In the early 1900s, urine was tested, too, using a chemical mixture that changed color if the patient had typhoid. In another test, a sample of feces was cultured. The bacteria that grew were examined through a microscope to see if they were Salmonella Typhi.

Today the Widal test is no longer considered dependable enough to diagnose typhoid fever. But it is still used, particularly in developing countries, because it’s simple to do and gives fast results. The most reliable diagnostic method is to culture a sample of bone marrow, although obtaining the sample is an invasive procedure that can be painful. Instead, cultures of blood, feces, and urine are more commonly used to confirm the presence of typhoid bacteria.