4

“AN ENEMY THAT MOVES IN THE DARK”

“Typhoid is one of the most difficult diseases to wholly extinguish in a place in which it has once gained a strong foothold.” —George Soper

By the end of February, 1,000 students—more than a third of Cornell’s student body—had fled the campus in fear for their lives. Some of them said they didn’t intend to return to Ithaca and Cornell ever again. Major newspapers throughout the United States were regularly reporting on the outbreak. This wasn’t the kind of publicity the university, city, or state wanted.

New York State Commissioner of Health Daniel Lewis was worried. Ithaca’s leaders had struggled to get the epidemic under control. Lewis doubted that the local health department could handle the problem alone. Ithaca desperately needed expert help.

The commissioner contacted George Soper. Lewis had been impressed by the sanitary engineer’s work in the fall of 1900, after a devastating hurricane killed more than 8,000 in Galveston, Texas. Soper had traveled there with a group to assist the Texans.

When he arrived in Galveston, Soper was shocked to find thousands of unburied bodies lying in the city’s ruins. “It was nauseating in the extreme,” he later said, “but it didn’t produce typhoid fever.” With typhoid, “there is more danger from the living than the dead.”

He recommended ways to set up effective sanitation in Galveston while the community cleaned up from the destruction. His advice prevented disease outbreaks like typhoid among the hurricane’s survivors.

Soper had rescued Galveston, and Commissioner Lewis wanted him to do the same for Ithaca. He asked the thirty-three-year-old to go there as a representative of the state health department.

George Soper felt confident that he could stop the outbreak’s spread. He had experience handling exactly this kind of challenge. So on Tuesday, March 3, 1903, he said good-bye to his wife, Mary Virginia, and their two little boys, George and Harvey, and boarded a train from New York City headed to the heart of the epidemic.

NO TIME TO WASTE

As his train made its way to Ithaca, George Soper peered out at the rolling hills, picturesque farms, and the occasional small towns of upstate New York. To some, it might have seemed an unlikely area in which to find an epidemic. But Soper knew that just one condition was needed for typhoid to spread: a single person excreting the bacteria.

When he stepped off the train at the Ithaca station that evening, he learned that the total number of sick had risen to 600. Six new cases had been reported that day, and four more were suspected. Nineteen Cornell students were dead and at least that many Ithacans. To Soper, it seemed like a “city … in a condition bordering on panic.”

Ithacans enthusiastically welcomed him because they’d heard about his reputation. The former president of the New York City Board of Health had called him “a competent, experienced, energetic man.” Leaders from the medical community had lauded his abilities as a sanitation engineer in the New York Times and the Journal of the American Medical Association.

Upon hearing that Soper was in charge of the Ithaca cleanup, a respected bacteriologist wrote: “It is certainly one of the hopeful signs of the times that a man of practical experience and energy, combined with scientific knowledge, should be placed in a position of authority.”

With thousands of lives at stake, Soper promptly went to work. The night he arrived, he met with Ithaca’s health officer to ask questions about the outbreak. The next day, he requested a tour of the city so that he could check out its sanitary conditions.

In a meeting on Wednesday evening, Soper warned Ithaca’s board of health, the city council, and representatives from Cornell that “the city stood in great peril and that drastic measures must be instituted to save it.” If they didn’t act now, he told them, the epidemic might continue for months or even years.

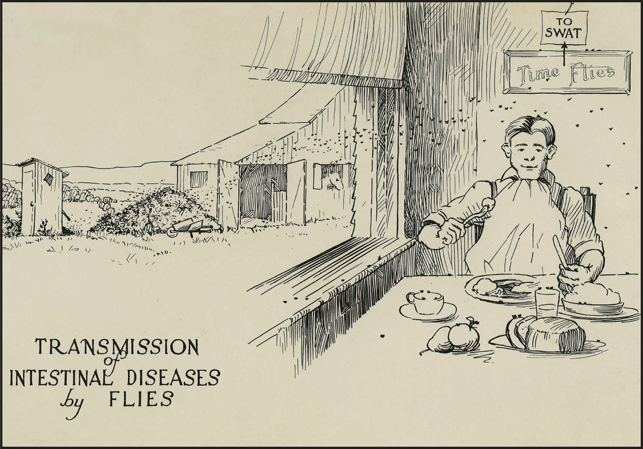

Typhoid patients would pass the bacteria on to people who hadn’t been made ill by the initial water contamination. Ithaca had to be sanitized as soon as possible and, Soper emphasized, definitely before spring. Warm weather would bring flies that could spread bacteria from the feces of infected patients.

The city council immediately voted to spend as much money as necessary to stop the typhoid outbreak.

Tall and handsome with dark hair and a mustache, George Soper impressed Ithaca’s residents when he spoke. After he made an appearance before the general public at the Music Hall, a local newspaper reported: “Dr. Soper is an earnest, learned and convincing speaker, and was most attentively listened to by the hundreds of persons present.”

Ithacans finally felt relief. This expert would help their city be healthy again.

KEEP BOILING

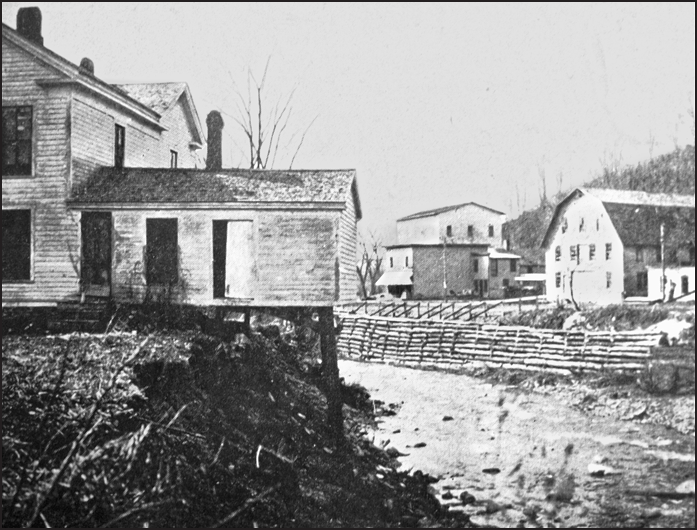

Soper set out to investigate the likely source of the epidemic—Ithaca’s water supply. Walking along the two creeks that provided water to the city and the one used by the university, he looked for places where human waste might have seeped into the streams. He saw plenty.

Scores of outhouses sat on the creek banks. Their contents oozed into the running water and turned the streams into sewers. On farms along the creeks, Soper discovered that men sometimes defecated in manure piles instead of in a privy. Rain and melting snow washed their waste into the nearby stream.

In the months before the outbreak, at least six people living along the creeks had been diagnosed with typhoid fever. Any of them might have been the original source of the epidemic. In one home, the excrement of a typhoid victim had been dumped in the snow on the creek’s bank. As the snow melted, the waste drained into the water headed to Ithaca.

Soper talked to Ithaca’s health department and learned that Six Mile Creek was considered the source of the outbreak. Many Ithacans blamed a team of sixty Italian immigrants who had worked along it. During the weeks before the epidemic began, the men had been building a dam for the water company. Sanitation at their camp had been poor, and some of them had defecated on the creek banks.

Soper found no medical reports of any workers having typhoid fever. Because they had since left town, he couldn’t verify that the Italian workers had been the source of the typhoid bacteria.

After examining the water supply, Soper concluded: “Among such a large number of sources of pollution as were obvious, it was difficult to discriminate. Any one of over a dozen might have been the cause.”

Although the original contamination by typhoid bacteria was probably over, testing showed that city water remained polluted. Soper warned Ithacans to keep boiling it.

As a permanent solution, he endorsed the city’s plan to install a filtration system. Soper had seen typhoid rates plummet in cities after they started to filter their drinking water. By percolating water through large beds of sand, these systems removed bacteria that caused waterborne diseases such as typhoid fever, dysentery, and diarrhea. Work on Ithaca’s new filtration system began at the end of March.

DESTROYING THE INVISIBLE

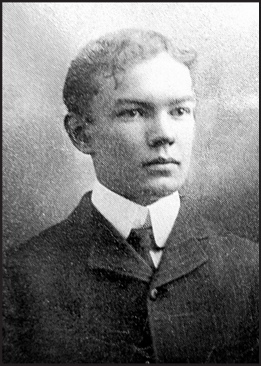

Meanwhile, the sick continued to lose their battle with the typhoid bacteria. On March 13, Cornell junior Schuyler Moore died at his widowed mother’s house a few miles up Cayuga Lake from Ithaca. “His death is deeply deplored,” a local newspaper said, “for it was believed that he had an excellent career before him.” Another life had been cut short on the verge of adulthood.

Even though the number of new cases had tapered off, Soper worried that the epidemic might still spread from the existing patients. He told the city council: “We are dealing with an enemy that moves in the dark. We cannot see the bacteria, and can only destroy them by cleaning and disinfecting the places where we believe them to exist.”

He recommended careful disinfection of every patient’s body waste and bedclothes as well as the outhouse or toilet where excrement was dumped. At his suggestion, the city hired twenty men who used four horse-drawn wagons to deliver the disinfecting chemicals—lime chloride and mercury chloride—to homes of typhoid patients. Soper made sure that residents also received printed instructions for using the disinfectants.

Caregivers were advised to wash their hands frequently so that they didn’t ingest bacteria or pass them on to others. When Dr. Alice Potter caught typhoid from one of her patients, Ithacans saw how contagious the lethal disease was. Three weeks later, the popular thirty-three-year-old physician died.

CLEAN THE CITY

Soper next turned his attention to the unsanitary conditions he had seen during his first tour of the city. Although Ithaca had a sewage system, many homeowners instead used their own outhouses or cesspools. Soper discovered that these were overflowing with “millions of typhoid germs.”

A team of fifteen men was hired to clean out and disinfect the 1,200 outhouses and 300 cesspools in the city. Horse-drawn wagons hauled 418,000 gallons of human waste to a field outside of town. It was plowed into twelve acres of ground to decompose.

Many Ithacans drew their drinking water from the 1,300 private wells in the city. Soper ordered testing to be sure they didn’t harbor bacteria. Nearly a third of these wells turned out to be so contaminated that he condemned them.

In one case, dirty water sickened 50 people and killed 5. They had all been drinking from a neighbor’s well in order to avoid the typhoid-carrying city water. Soper discovered that a leaky drainpipe from the house’s toilet ran close to the well and carried waste into the drinking water.

The well’s owner had been ill with what her doctor called grippe. A blood test later showed that she had typhoid fever. The woman, who generously shared her well water, unknowingly spread the disease to her neighbors with deadly results.

George Soper found out that most of the infected college students lived and ate their meals in boardinghouses. Male students stayed off campus because Cornell provided dormitory rooms only for women. He had each of the dozens of boardinghouses inspected, with a focus on the plumbing, inside bathrooms, and water supply. Owners were told how to fix sanitation problems. The boardinghouses that passed reinspection received a permit to operate.

Ithacans respected Soper’s advice. One student, reluctant to return to Cornell until the risk of disease was gone, wrote President Schurman: “Do you think that . . . there is any great danger of secondary infection? Could you inform me what Dr. Soper’s opinion is on this question?”

THE EPIDEMIC ENDS

At seven in the morning of May 6, the twenty-ninth Cornell student died. Leslie Atwater had grown up in Ithaca and was well liked for his “pleasing, generous disposition.” His many friends were devastated by his death. A “bright light goes out,” lamented the Ithaca Daily News. Leslie was officially the last Cornell student to die in the epidemic. He was less than two months from graduating.

The frightening, sorrowful months of disease and death pushed the university and city to make changes. Cornell decided to build dormitories for male students so that they would not be forced to live in the city’s boardinghouses. The university built its own filtration plant to clean the water it pumped from one of the three local creeks.

Ithacans voted to take public control of the city’s water system away from the private company whose bad management many blamed for the outbreak. New regulations banned sewage from being dumped into local streams. The city set standards for building and maintaining outhouses.

At the end of August 1903, more than seven months after the epidemic started, Ithaca’s new filtration plant was in place. George Soper assured residents that the new system would “eliminate 97 or 98 per cent of bacteria” and “the water will be acceptably pure.” Homeowners noticed the difference. “When I took my bath this morning,” said one, “the water was as clear as a whistle.”

By September 1, Soper’s work was finished. The bill for six months of his services was about $2,300. This was a substantial fee when the average annual household income in New York State was $675. Commissioner of Health Lewis pointed out to Ithaca’s leaders that “all sanitarians who are familiar with Dr. Soper’s qualifications . . . regard his services as cheap at any price.”

The cost of cleaning up the city, including the filtration system, totaled more than $100,000.

A PRICE TOO HIGH

The victims of the epidemic owed enormous bills for doctors, nursing care, and medicine. The cost of three months of care for one patient could be $450 or more, an amount difficult for most families to pay.

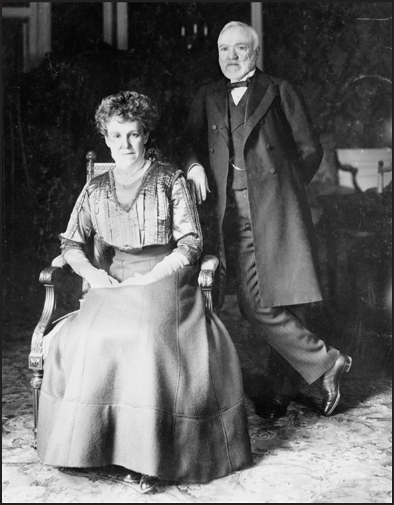

City residents had to deal with these expenses themselves. Fortunately for the hundreds of Cornell students who suffered, a wealthy member of the university’s board of trustees, industrialist Andrew Carnegie, paid their bills.

Carnegie understood typhoid’s toll because it had almost killed him earlier in his life. Several years later, the disease left his wife so weak that she couldn’t walk for three months. Carnegie donated tens of thousands of dollars to pay for student medical bills and for the university’s new filtration system.

The cost in lost and damaged lives was incalculable. About 1 in 10 Ithacans—1,350 victims—developed typhoid fever and spent long months recovering. Of those, 82 died, including 29 Cornell students.

George Soper believed that the actual total would never be confirmed Recordkeeping had been incomplete, and an unknown number of people connected to the outbreak had died elsewhere. Some students infected in Ithaca went home and spread the disease to family members, who became ill and died.

The typhoid epidemic left countless broken hearts. A widow visited Cornell’s president after her son died. She told Jacob Schurman that the young student had been “the sole stay of her declining years.” Now she was alone.

Theodore Zinck, a German immigrant who owned a downtown bar popular with Cornell students, became a victim even though he was never sick. His only child, twenty-four-year-old Louise, was struck down during the first weeks of the outbreak. She seemed to be improving, but she took a turn for the worse and died on February 24. That summer, after enduring four months of unbearable grief, Theodore rowed a boat into the middle of Cayuga Lake and drowned himself.

In Soper’s view, the tragic epidemic should have been prevented before a single Ithacan fell ill. He later said, “Seldom has so terrible a lesson of the consequences of sanitary neglect been given.”

He was determined to stop this from happening again in a different town to other innocent victims.