6

A THREAT TO THE CITY

“We have here, in my judgment, a case of a chronic typhoid germ distributor.” —George Soper

The satisfaction George Soper felt in finding Mary Mallon soon disappeared. Two members of the Bowne household had recently become victims of typhoid fever. A female servant had been taken to the hospital. The second patient was one of the Bownes’ two children, a twenty-five-year-old daughter named Effie, “a beautiful and talented girl.”

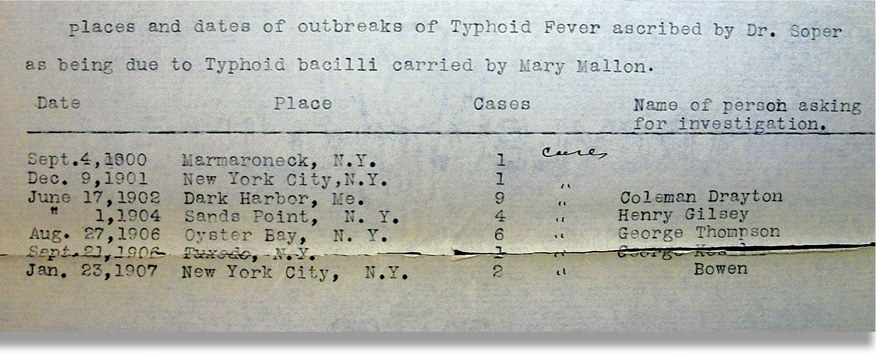

Soper’s investigation had revealed a disturbing pattern. He had traced eight of the households where Mallon worked in the previous ten years. In seven of them, someone developed typhoid fever while she was the cook—a total of 24 people. Yet even when other servants fell ill, she never did. The outbreaks had been the only typhoid cases at the time in those neighborhoods or communities.

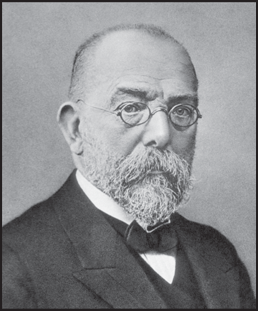

The facts troubled Soper. Mary Mallon might be one of the typhoid carriers that the German scientist Robert Koch had recently described. Despite being in good health, was she harboring typhoid bacteria in her body and spreading them to others?

From a scientific point of view, Soper realized this was an exciting discovery. Mallon was the first case of a healthy typhoid carrier ever found in the United States. But from a public health standpoint, it was chilling. “Under suitable conditions,” he feared, “Mary might precipitate a great epidemic.”

To confirm his suspicions, George Soper needed irrefutable proof that Mallon was the source of the outbreaks. It was possible that her connection to these cases had been an unfortunate coincidence. After all, typhoid fever was widespread in the New York area. In 1905, more than 4,300 cases and nearly 650 deaths had been confirmed in the city. Soper was sure there were many more that hadn’t been correctly diagnosed or reported by doctors.

He saw just one way to prove that Mary Mallon was a carrier: test her body for typhoid bacteria.

CONFRONTING THE COOK

Soper headed to the Bownes’ Park Avenue home to talk to Mallon. He found her in the kitchen wearing a white apron. The stove warmed the room on the frosty February day.

A tall woman at five feet six inches, Mary Mallon had blue eyes and blond hair pulled back into a tight knot. She looked strong and healthy to Soper, perhaps even a bit overweight. She obviously was neither suffering with typhoid symptoms nor recovering from a recent bout.

He tried to be tactful when he explained the situation. He assumed she wondered why people kept getting typhoid fever wherever she worked. Hadn’t it ever occurred to her that she might have something to do with the outbreaks?

“I had to say I suspected her of making people sick,” Soper recalled. It wasn’t her fault, he assured her, but there was a good chance she was spreading typhoid through the food she prepared. He offered to show her how to stop infecting others by washing her hands and being careful with her excretions.

“I thought I could count upon her coöperation in clearing up some of the mystery which surrounded her past,” he said later. He hoped Mallon would tell him about other places she’d worked.

“I wanted specimens of her urine, feces and blood,” Soper remembered telling her. “If she would answer my questions and give me the specimens, I would see that she got good medical attention, in case that was called for, and without any cost to her.”

George Soper was stunned by Mary Mallon’s reaction to what he considered a reasonable request. With her eyes full of hostility, she chased the epidemic fighter out of her kitchen.

Seeing her fury, Soper took the hint and fled down the hallway and through the iron gate that led out to the sidewalk. “I felt rather lucky to escape,” he later wrote, admitting that maybe he hadn’t handled her very well.

THE SURPRISE VISIT

Frustrated, Soper decided to try a different approach to get Mallon’s cooperation. He had to make her understand her role in the outbreaks. She didn’t seem to appreciate how important it was to give him the information and specimens he needed.

By asking around, Soper discovered that Mallon had a boyfriend in Manhattan named A. Briehof. The man lived in a Third Avenue tenement room and spent his days in a bar on the nearby corner. Soper sought him out. He persuaded Briehof to alert him the next time Mallon was coming to visit. But Soper asked Briehof not to tell her about their conversation.

On the arranged evening, Soper went to the tenement. He took along his physician friend and former assistant from the Ithaca outbreak, Dr. Bert Raymond Hoobler. The plan was for Hoobler to help obtain the specimens.

The two climbed the staircase to Briehof’s room on the top floor, where they waited. Soon they heard Mallon’s footsteps on the stairs.

When she spotted George Soper at the top, she was first startled and then incensed.

Once again, Soper tried to explain that she might be spreading typhoid fever germs. He told her that he “meant her no harm.” He just wanted a sample of her urine, feces, and blood for testing.

Soper’s words only made Mary Mallon angrier. In her Irish brogue, she demanded to know how anyone could accuse her of such a thing. She was a clean person, couldn’t they see? She worked for reputable employers who wouldn’t hire someone who was dirty. She was healthy and always had been. She had nothing whatsoever to do with anyone catching typhoid. Why, in fact, five years ago she had put herself at risk to help cure the family at Mr. Drayton’s Maine summer home.

George Soper saw that Mallon wasn’t going to let him take the specimens. With her curses echoing in the stairwell, he and Hoobler retreated down the stairs and into the street, relieved to get away from the outraged woman.

DANGER TO THE COMMUNITY

On Saturday, February 23, after a two-week illness, Effie Bowne died. The funeral was held at the Bownes’ home the following Tuesday morning. Soper later wrote that the family was “prostrated with grief” at the death of their only daughter.

Effie Bowne was the first fatality that Soper had connected to Mary Mallon, and it raised the stakes. In Ithaca and other cities, Soper had seen the misery brought on by typhoid. This cook could be a threat to every person with whom she had contact. He had tried to reason with her, but he’d failed. Someone with more authority would have to deal with her now.

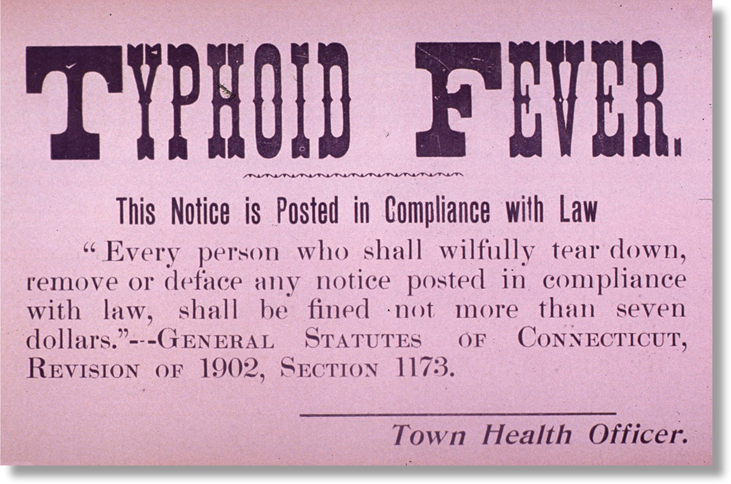

Soper collected his evidence of Mallon’s ten-year trail of typhoid fever. On Monday, March 11, 1907, he presented it all to Dr. Hermann Biggs, the general medical officer at the New York City Department of Health. Soper had worked as a sanitary engineer for the Department in 1902. He knew it had the legal power to examine the cook, even taking her into custody if she wouldn’t voluntarily provide specimens for testing.

If Mary Mallon was a carrier, as Soper suspected, she was a “menace to the community.” She had to be stopped.

The Healthy Carriers

By the end of the nineteenth century, scientists knew that typhoid fever was caused by bacteria spreading from human to human. But they wondered why typhoid suddenly appeared in areas where no one had been sick with it before. If there was no obvious source of the disease, such as contaminated water or food, how did the bacteria get there?

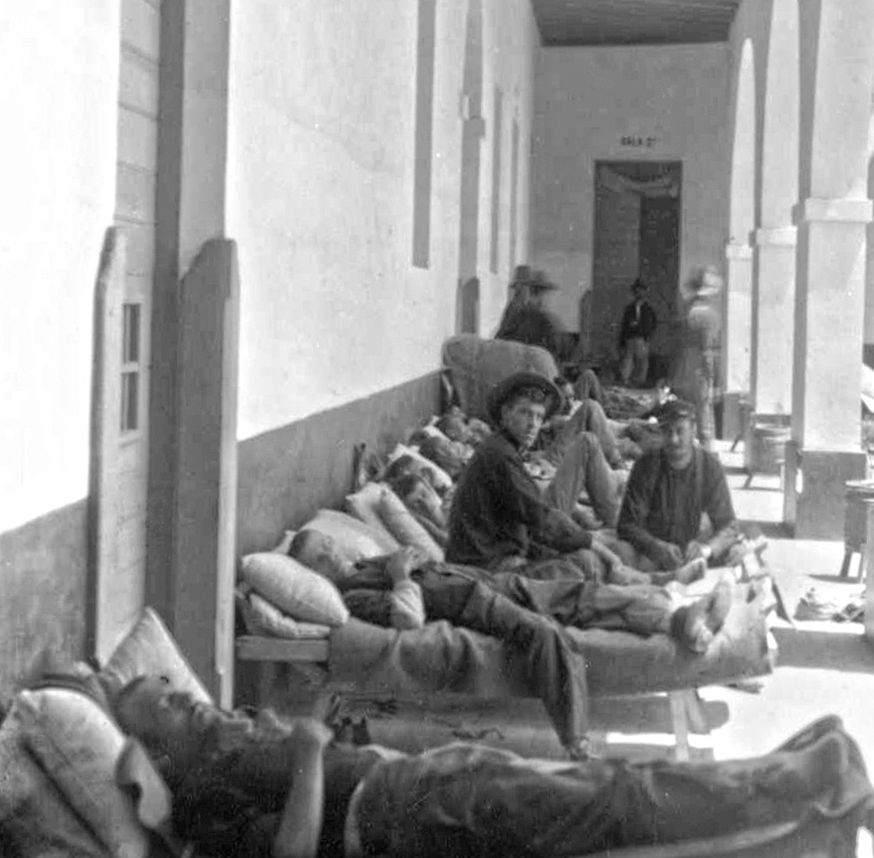

A clue came during the Spanish-American War of 1898. Typhoid fever broke out among almost every volunteer regiment in United States training camps, striking 1 in 5 soldiers. Yet not a single soldier with symptoms of the disease had been allowed into the camps.

After investigating, a team of U.S. Army doctors concluded that some soldiers who looked and felt healthy must have carried the typhoid bacteria. In their report, the doctors wrote that “the specific germ of this disease . . . when cast out in the stools [feces] may become a source of danger to others.” Typhoid spread easily under the often unsanitary conditions in military camps.

Soon after, Robert Koch studied a typhoid outbreak in several German villages. He tested the excrement of residents, using new culturing methods that detected typhoid bacteria. He discovered the germs in people who were not sick.

In November 1902, Koch gave a speech to other scientists in Berlin during which he discussed healthy carriers of the typhoid bacteria. These people had recovered from typhoid fever or experienced such mild cases that they never knew they had it. In most patients, either the body’s immune system destroys the bacteria or the patient dies. But in a carrier, the bacteria continue to live and multiply and are periodically discharged in feces or urine.

By 1906, when George Soper began investigating the Oyster Bay outbreak, he had read Koch’s speech. This led him to track down Mary Mallon, whom he suspected was a carrier.

Later studies showed that about half of typhoid patients give off the bacteria in their feces, and occasionally in their urine, for a month after recovering from symptoms. About 20 percent still shed the bacteria after two months, and 10 percent after three months.

Approximately 5 percent of recovered patients have Salmonella Typhi in their excrement more than a year after disease symptoms are gone. They are the chronic typhoid carriers. Three times as many women as men harbor the bacteria without becoming sick. Children rarely become carriers.

The bacteria usually settle in the gallbladder, where bile is stored. They may also be found in the bile ducts, liver, or kidneys. In some carriers, they remain there for decades, ready to infect others.

Typhoid carriers live, on average, as long as anyone else. But they are more likely to have gallstones and may be more susceptible to cancer of the gallbladder, bile duct, and pancreas. One carrier lived to be 101 years old, carrying the bacteria in her body for eighty years without becoming sick.