8

INSIDE THE WHITE WALLS

“She is practically a human vehicle for typhoid fever germs.” —New York American

Maybe she wasn’t as book-smart as Soper, Baker, and all the doctors at this hospital. But Mary Mallon knew she wasn’t stupid, either. How could she give typhoid fever to someone when she wasn’t sick herself—and never had been? It didn’t make sense.

She’d worked hard to get where she was. She wanted to be left alone so that she could get on with her life.

That life had started in Cookstown, County Tyrone, in what is today Northern Ireland. Born on September 23, 1869, Mary Mallon was only four months older than George Soper. While young George’s ticket to prosperity was a college education, Mary’s ticket to a better future was passage on a ship to America. The day she left her birthplace in 1883, she joined millions of other immigrants who had escaped a hard, wretched existence in Ireland.

Mary was about fourteen when she arrived in New York City, almost the same age Josephine Baker was when her father died. Mary had grown up in a tight-knit town of fewer than 4,000 residents. She had to adjust to a crowded city of nearly 1.5 million in which 4 out of every 10 people had been born in another country.

At first, Mary lived with her aunt and uncle. But after they both died, she was on her own with no relatives in America and no one to support her. The two best job options open to a young, single Irish woman were factory worker and domestic servant. Mary chose cooking. She was good at it, and besides, cooks earned more than maids or laundresses.

Mary built up her reputation until she was working regularly for wealthy families. At a time when only a quarter of all workers in New York were women, she managed to fend for herself, living either in an employer’s home or with one of her friends.

At age thirty-seven, Mary Mallon’s life was going well … until the day George Soper walked into her kitchen.

TEEMING

From the minute they took her inside the doors of Willard Parker Hospital, Mallon was trapped.

New York City’s health department had set up the hospital to care for patients with serious, and often fatal, contagious illnesses. Before antibiotics, most infectious diseases had no cure, and private hospitals were reluctant to accept these patients.

People with scarlet fever, measles, and diphtheria were brought to Willard Parker. There they were isolated from the public so that they didn’t set off an epidemic. The brick hospital had about two hundred beds, but it sometimes had three times as many patients.

Now that they finally had Mary Mallon, the health department officials wasted no time checking her for typhoid. The tests would be carried out by the Bureau of Laboratories, headed by Dr. William Park.

Park’s interest in typhoid fever and the bacteria that caused it was both professional and personal. During the summer of 1896, he had been sick for several weeks with typhoid. Park blamed himself for being careless. While on a long bike ride about fifty miles northwest of the city, he became extremely thirsty and drank from a lake. The water turned out to be contaminated.

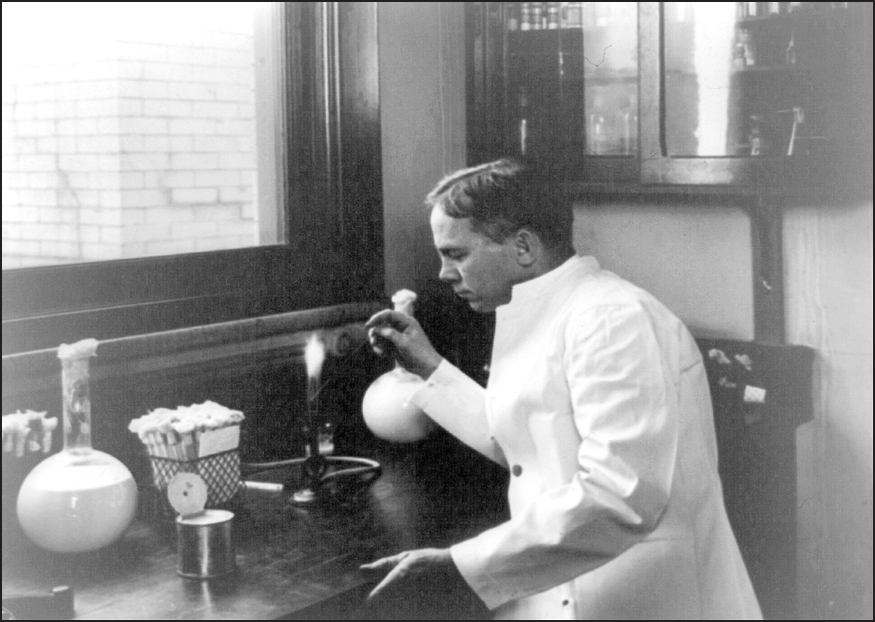

Under Park’s direction, bacteriologists in the laboratory tested Mallon’s urine and blood for typhoid. They also took samples of her feces, put them in an incubator, and examined the bacteria that grew.

The test results surprised Park and others in the health department. Her urine contained no typhoid bacteria. Many physicians believed urine was a major way that the bacteria spread.

The Widal blood test revealed a different story. It showed that Mallon’s body contained antibodies against typhoid bacteria.

When Park saw the test results on her feces, he was astounded. The samples were teeming with typhoid bacteria. Mary Mallon, he said, was “a human ‘culture tube.’”

George Soper’s suspicions had been correct.

Doctors at the hospital gave Mallon a physical exam, looking for symptoms of typhoid fever. Just as Soper and Baker concluded when they first saw her, Mallon was healthy and “rosy-cheeked,” looking nothing like a sick or recovering typhoid patient.

Even though Mallon didn’t appear to have typhoid fever, the lab tests showed that the bacteria had definitely entered her body earlier in her life. She either didn’t remember having symptoms or had suffered a mild case. It was also possible that she was lying when she said she had never had typhoid.

What mattered to the health department was that those dangerous bacteria were still inside her, reproducing and being shed in her feces. Baker’s boss, Walter Bensel, called Mallon a “living fever factory.”

NOW WHAT?

The New York City Department of Health was holding the nation’s first healthy typhoid carrier. But as Walter Bensel commented, “The Lord only knows what we can do with the woman.”

How could they prevent Mallon from infecting anyone else? No one had yet discovered a treatment guaranteed to destroy the typhoid bacteria inside a carrier’s body.

European researchers had found typhoid bacteria in the gallbladder during operations to remove gallstones and during autopsies of carriers. Based on that discovery, some physicians claimed that they could cure a carrier by taking out his gallbladder.

But the surgery was controversial. Cautious doctors warned that it might not work. Typhoid bacteria likely hid in other parts of the body, too. And any surgery was risky and could lead to infection, bleeding, or other side effects that might kill the patient.

The doctors at Willard Parker thought it was worth a try, anyway. They asked Mallon if they could perform the surgery.

She refused. These people were not going to cut her open and take out her insides.

PEEP SHOW

The laboratory’s results turned Mary Mallon’s life into a nightmare. She knew they were wrong. She felt perfectly healthy. How could she be full of millions of germs?

Yet the doctors acted as if she had some strange, new disease. They asked her the same questions over and over again. Had she ever had typhoid fever? No! Had she been aware that she was making people sick? No!

The hospital moved her from the wards to a private room, where even more doctors crowded around her bed, discussing her case. Mallon was outraged. “I have been in fact a peep show for Evrey [sic] body,” she complained.

Her room was drab and sterile, and she hated staying there. Hospital attendants guarded the door to stop her from escaping. The walls were white, the floors were white, the ceiling was white. It was a white prison.

About two weeks after Mallon had been dragged to Willard Parker Hospital, a couple of New York newspapers picked up her story. According to them, an Irish cook was being held by the health department. Her name was Mary Ilverson, and she was “a human vehicle for typhoid germs.”

When reporters interviewed Walter Bensel, he explained why she’d been detained: “This woman is a great menace to health, a danger to the community, and she has been made a prisoner on that account.”

The health department hid Mallon’s real identity and the names of the “prominent families” to whom she passed the typhoid germs. One of the newspapers incorrectly said that the cook was being held prisoner at Roosevelt Hospital. The other stated she was in Bellevue Hospital.

But on one point, the articles about Mary were accurate. “Her language is far from cordial or gentle,” wrote the reporter, “when the doctors visit her and talk of her internal storehouse of germs.”

AN OFFER OF HELP

One day, Mary Mallon had an uninvited visitor to her white prison. She wasn’t happy to see him. What did Dr. George Soper want with her now? Because of him, the health department had grabbed her and locked her up in this hospital.

Soper immediately started talking. He’d been right, he told her. The lab results proved that she had once had typhoid. She should stop denying the truth and being so stubborn. That’s what had gotten her arrested in the first place.

Mallon stared at him, her anger growing. Soper seemed to be gloating.

“Many people have been made sick and have suffered a great deal; some have died,” he continued. He told her that none of it would have happened if she had washed her hands after using the toilet. “You don’t keep your hands clean enough,” he scolded.

Glaring, Mallon said nothing.

Soper went on with his speech, claiming that he could get her out of the hospital. He urged her to start cooperating and let the doctors take out her gallbladder. It was the best way to get rid of the germs. “You don’t need a gallbladder any more than you need an appendix,” he said.

Soper leaned against the door as he explained what he could do to help her. He intended to write a book about her case so that others would learn about typhoid carriers. Would Mary tell him when she’d had typhoid, where she’d worked, and who else might have gotten the fever from her? He promised not to use her real name, and he’d give her the profits from book sales.

Mallon had heard enough. Seething, she wrapped her white robe around her body, crossed the floor to the bathroom, and slammed the door shut.

QUARANTINE ISLAND

Several times a week, the laboratory tested Mallon’s feces. The typhoid bacteria were still there. With her body shedding deadly germs, the doctors believed she remained a threat to the city. The health department had held Mallon in isolation against her will for about a month. Nothing could stop it from keeping her longer.

Since 1866, the New York City Board of Health had had broad powers. Out of concern about a cholera epidemic, the New York State Legislature had given the Board the authority to do whatever was necessary to protect the city’s health. That included using the police to enforce quarantines and isolation of infected people. Health officials didn’t need court permission to act.

Josephine Baker later observed: “There is very little that a Board of Health cannot do in the way of interfering with personal and property rights for the protection of the public health.”

Officials decided to use that power to keep Mary Mallon in custody. But they’d have to find somewhere else to put her. Willard Parker Hospital needed Mallon’s room for other patients.

The health department operated a quarantine hospital on North Brother Island in the middle of the East River. Riverside Hospital, built in the 1880s, had once been used to isolate people with highly contagious diseases such as typhus and smallpox.

In 1903, due to the efforts of Hermann Biggs, Riverside instead became a sanatorium for tuberculosis victims. The hospital treated patients who were expected to recover. It also held some people under “forcible detention” because they couldn’t be trusted to stop spreading their tuberculosis germs.

Mary Mallon was to be the Island’s first typhoid case under forcible detention. The only way on and off was by boat. They weren’t going to keep her behind bars, but as far as Mary was concerned, North Brother Island was a jail.