9

“THE MOST DANGEROUS WOMAN IN AMERICA”

“No knife will be put on me.” —Mary Mallon

The ferry ride across the polluted East River to North Brother Island covered a quarter of a mile. Mallon felt as if she were being taken thousands of miles away from her world.

She’d heard of North Brother Island from the headlines. Three years before, in June 1904, the steamship the General Slocum burned and sank nearby. About 1,400 German Americans had been onboard, most of them women and children heading to a church picnic. More than a thousand of them died, and their bodies washed up on the Island’s shore.

People had been dying there for years. North Brother Island was a place where you were sent to die, away from your family and friends. Being on the Island made Mallon feel “nervous & almost prostrated with greif [sic] & trouble.” She didn’t belong. She wasn’t sick, and she wasn’t dying.

The kidney-shaped island covered about twenty acres, less than the area of four blocks in Manhattan. It contained a few trees, a church, a red-and-white lighthouse, some concrete buildings and wooden cottages, and the brick hospital full of tuberculosis patients. Mallon was glad they didn’t make her stay in there.

Right: Bodies are lined up on the Island’s shore.

Instead, they put her in a cottage at the southern end of the island that had once been the head nurse’s home. The building wasn’t large, but its many windows made it bright—definitely an improvement over the cramped room they’d locked her in at Willard Parker Hospital. She had a living area with a bed, table, small kitchen, and a bathroom with modern plumbing.

The cottage sat near the riverbank next to the church. From the porch, Mallon could see the buildings of Manhattan, where she’d once lived and worked … and now was forbidden to go.

BACTERIA FIGHTING

The health department doctors continued to monitor the typhoid bacteria in Mallon’s body. At first, they asked her to provide samples of her feces three times a week for testing in the department’s laboratory. She was relieved when, in November 1907, they cut back to once a week. But that didn’t make her any less indignant about the way she was being treated.

They told her that they were trying to cure her. If they succeeded, they’d be able to release her, knowing that she couldn’t infect others.

Off and on, the doctors gave her urotropin, a drug used to cure urinary-tract infections. The idea was that the drug would kill the bacteria in Mallon’s bladder before the urine left her body.

When the urotropin didn’t seem to reduce the amount of bacteria that Mallon shed, the doctors stopped giving it to her. Good thing, too, because the side effects made her miserable. “If I should have continued,” she complained later, “it would certainly have killed me for it was very severe.”

Next, the doctors tried several drugs that destroyed other types of microbes. They fed her brewer’s yeast because it seemed to cure various ills. They changed her diet and gave her laxatives, hoping that would help. Nothing worked. At times, her feces were free of typhoid bacteria for as long as three or four weeks. But the microbes always reappeared.

Mallon couldn’t trust the doctors. They didn’t seem to know what they were doing or care about her. Their sole concern was the germs they claimed she carried. When her left eyelid became paralyzed, she asked them for help. No one did anything. After six months, the eyelid got better. In Mallon’s opinion, it was “thanks to the Almighty God,” not the doctors.

WHAT ABOUT THE OTHERS?

Mary Mallon’s capture and imprisonment raised new questions for the health department. Investigators had been lucky to find her, but surely she wasn’t the only healthy typhoid carrier walking around the city.

The Europeans thought that 5 percent of typhoid patients became lifetime carriers. With more than 4,000 New Yorkers developing the disease in 1907 alone, that meant that thousands of carriers like Mary Mallon were living in the city. How could the health department stop them all from spreading typhoid bacteria and infecting others?

William Park, who directed the laboratories, and Walter Bensel, who had overseen Mallon’s capture, both spoke out about the problem. They agreed that the city had so many carriers that they couldn’t possibly lock up all of them.

But Health Commissioner Thomas Darlington was proud of the drop in the typhoid fever death rate since he took office in 1904. Twenty percent fewer New Yorkers had died of typhoid despite the city’s growth by half a million people over the past five years. He didn’t want to release a woman known to have caused several typhoid outbreaks.

AN OFFER OF FREEDOM

The health department doctors again explained to Mallon that they wanted to help her return to her previous life. But first they had to eliminate the typhoid bacteria from her body.

The best way—maybe the only way—was to take out her gallbladder, where typhoid germs were living and dividing. They promised to get “the best surgeon in town to do the cutting.”

Mallon refused. “No knife will be put on me. I’ve nothing the matter with my gall bladder.”

The head nurse tried to persuade her. “Would it not be better for you to have it done than remain here?”

Mallon said no, it would not. She wondered if they were trying to commit murder by slicing into her: “I’m a little afraid of the people & I have a good right.”

By January, ten months after Mallon was taken from the Bownes’ house, doctors had failed to cure her. The health department tried another strategy. One of the Riverside Hospital doctors asked her: If she were allowed to leave the Island, where would she go?

Mallon didn’t hesitate. “To N.Y.,” she replied.

That wasn’t the answer the New York City Department of Health wanted to hear.

Later, the head nurse brought up the subject with Mallon. The city might let her go if she said the right thing. She should write to Commissioner Darlington, the nurse suggested. Tell him that if he released her, she’d leave New York, change her name, and go live with her sister in Connecticut.

Mallon replied that she couldn’t do that for one simple reason: “I have no Sister in that state or any other in the U.S.”

MARY FIGHTS BACK

By July 1908, Mary Mallon had been imprisoned for more than a year. She had adopted a small fox terrier as a companion, and her boyfriend, Briehof, was allowed to visit. Still, her life on the Island was boring and dismal. For many years, she had been used to working. Now she had nothing to keep her busy.

The health department wouldn’t let her go. They said it was because she was giving off typhoid bacteria. Well, Mallon didn’t believe it. She had never believed it, and she was determined to prove them wrong.

Briehof agreed to help. For the next nine months, he took samples of her feces and urine to Manhattan for tests at a private laboratory.

Every report from Ferguson Laboratories came back the same: “This specimen shows no indication of Typhoid Fever.” One report said that her urine and feces were negative; however, her blood suggested that “a condition of Typhoid existed at some previous time but not at present. There will be no danger of communicating the ddisease [sic] to another throught [sic] the medium of cooking.”

That was the proof Mallon wanted. The health department had no right or reason to keep her locked up.

Her resentment grew when she learned that the health department’s William Park had written an article about her. In September 1908, it was published in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

Park wrote that Mary (he didn’t give her last name) couldn’t be released because she had infected more than two dozen people. During a discussion of the article at a medical conference, Dr. Milton Rosenau, director of the U.S. Public Health Service Hygienic Laboratory, referred to her as “typhoid Mary.”

Mallon was livid: “I wonder how … Dr. Wm. H. Park would like to be insulted and put in the Journal & call him or his wife Typhoid William Park.”

BREAKING NEWS

For almost two years, Mary Mallon stood alone against New York City and its health department. In the spring of 1909, an Irish attorney named George Francis O’Neill came to her rescue.

O’Neill was in his early thirties and had been practicing law in New York for about two years. No one knows how she arranged to hire him. Some say that William Randolph Hearst, the powerful newspaper publisher, paid O’Neill’s legal fees, perhaps to get her story.

However it happened, reporters at Hearst’s New York American newspaper found out Mary’s last name and the details of her capture and imprisonment. On Sunday, June 20, 1909, the paper’s 800,000 readers found out, too.

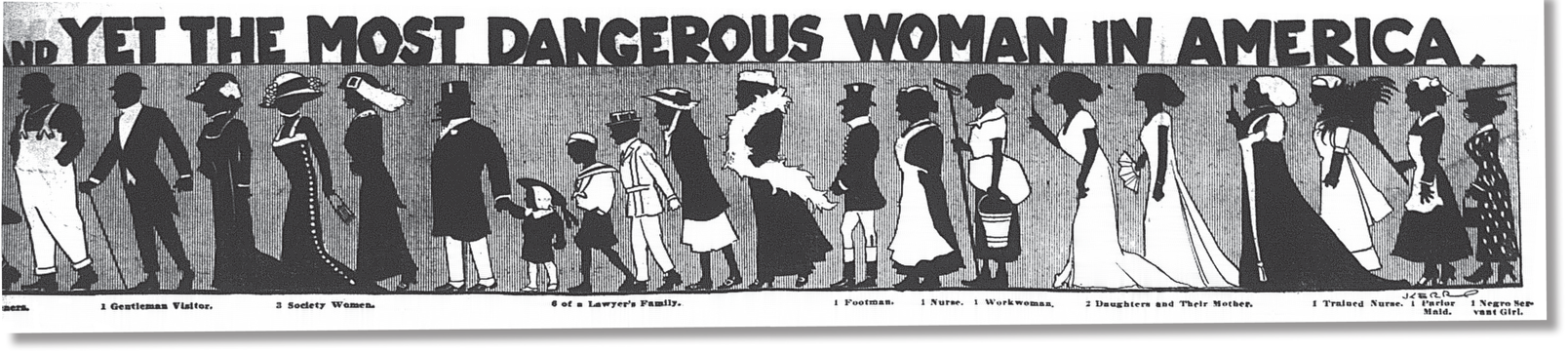

A blaring headline stretched across two pages in the magazine section: “‘TYPHOID MARY’ MOST HARMLESS AND YET THE MOST DANGEROUS WOMAN IN AMERICA.” Below the headline was a drawing depicting a parade of her victims, including 4 laundresses, 1 parlor maid, 1 footman, 1 nurse, and 3 society women. The list was loosely based on George Soper’s investigation.

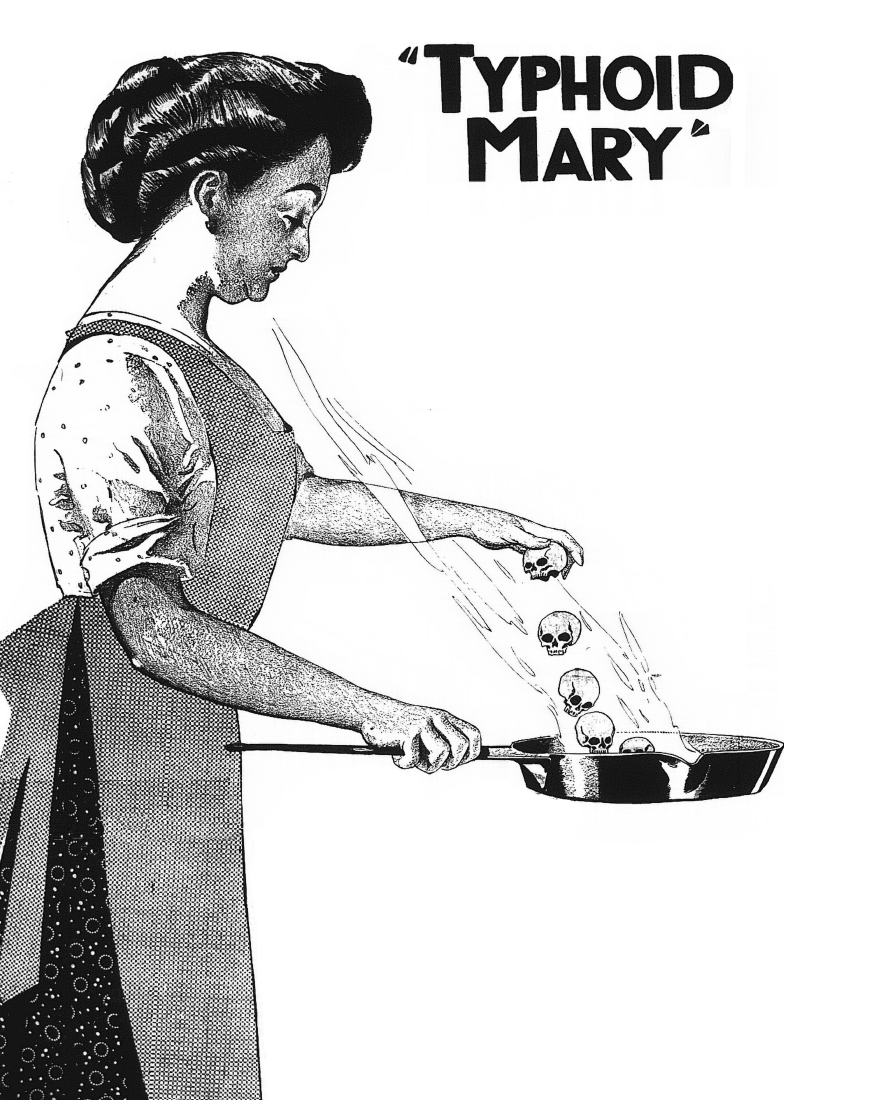

In its sensational article, the newspaper identified the cook Mary Mallon as “Typhoid Mary.” A drawing showed her breaking skull-like eggs into a frying pan. An interview with George Soper recounted her “Extraordinary Trail of Death and Disease.”

William Park was quoted, too, reassuring the public that Mary didn’t spread typhoid fever through casual contact. It was through her cooking. “It is extremely unfortunate for the woman,” Park said, “but it is the plain duty of the health authorities to safeguard the public from such a menace.”

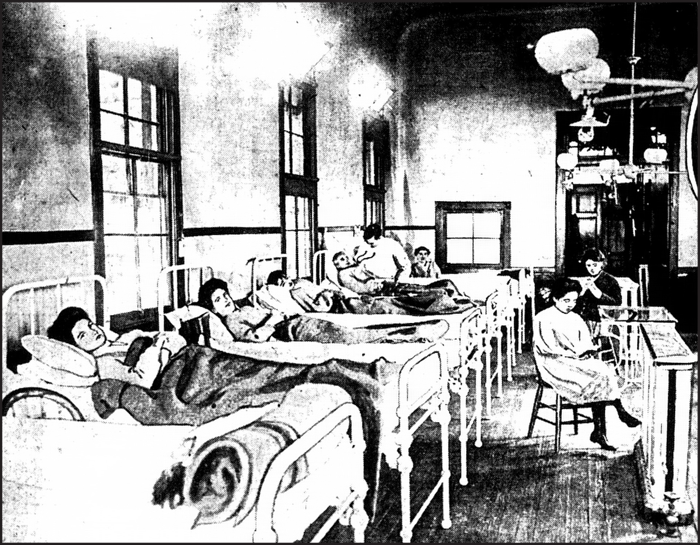

Although the newspaper made Mary Mallon look like a killer, it also expressed some sympathy for her. It described her as “a prisoner on New York’s quarantine island.” In one photograph, she is confined to a bed in Willard Parker Hospital. In another, she is huddled against a building on North Brother Island with a blanket wrapped around her to keep warm.

Mary, the newspaper said, “has committed no crime, has never been accused of an immoral or wicked act, and has never been a prisoner in any court, nor has she been sentenced to imprisonment by any judge.”

PLEA FOR FREEDOM

These words sounded as if they could have come from a lawyer’s mouth. In fact, that might have been exactly where the reporter got them. George O’Neill’s tactic for freeing his client was to argue that Mallon had done nothing wrong. Yet she’d been imprisoned without a court hearing or trial.

On Monday, June 28, 1909, O’Neill filed a writ of habeas corpus (which means “you have the body”) in the New York State Supreme Court. In this legal document, he asked a judge to require the superintendent at Riverside Hospital to produce Mary Mallon and explain why she was being held.

A Supreme Court justice ordered the health department to bring Mallon from North Brother Island to the Supreme Court building in Manhattan the next day. She was finally getting her day in court.

On Tuesday morning, reporters from the New York newspapers were waiting for her at the courthouse. After the New York American’s article nine days before, Typhoid Mary Mallon had become famous, and her nickname stuck. News about her sold papers.

Mallon hadn’t been off the Island for about two years, and she took advantage of the chance to share her outrage. “I have committed no crime,” she announced to reporters, “and I am treated like an outcast—a criminal. I … have always been healthy.”

She looked it, too. Reporters described her “as rosy as you please” and having “a clear, healthy complexion, … bright eyes and white teeth.” It seemed remarkable to them that she could be full of deadly typhoid bacteria.

Mallon pulled out a copy of the New York American article with a picture of her dropping skulls onto a skillet. “It’s ridiculous to say I’m dangerous,” she said.

She complained that no one ever spoke to her on the Island. A nurse dropped off meals at her door three times a day and rushed away. “Why should I be banished like a leper and compelled to live in solitary confinement with only a dog for a companion?” she asked.

To some newspaper readers, it seemed unlikely that doctors and nurses who regularly treated lethal contagious diseases would ostracize Mallon. The New York American had printed a photo of her sitting with other women against a building on North Brother Island, clearly not in solitary confinement.

“It was the drinking water, not me that caused the trouble,” Mallon insisted. “I never had typhoid in my life.”

Not everyone agreed. One reporter quoted an unidentified health department doctor: “If she should be set to work in a milk store to-morrow in three months she could accomplish as much as a hostile army.”

At the court hearing, the attorney representing the health department explained why Mallon was held in a contagious hospital: she is “a menace to the health of the community.” The doctors were attempting to cure her infected condition, he said. She still had large amounts of bacteria in her stools, however, and should not be allowed to go free.

The attorney asked for an adjournment so that he could better prepare his case. The justice agreed, sending Mallon back to North Brother Island.

She’d been off the Island for just three hours. “I don’t want to go back,” she said. “It’s very lonely over there.”

But back she went.

THE ARGUMENTS

During the next two weeks, the lawyers on both sides argued their positions in papers submitted to the Court.

The health department’s attorney provided the evidence gathered by George Soper, tracing the typhoid cases caused by Mary Mallon. A Department of Health doctor stated that “The repeated outbreaks … were in themselves proof that the virulence of the bacilli had remained intact.”

To back up its case, the Department’s attorney gave the Court twenty-eight months of its laboratory tests. From March 1907 to June 16, 1909, the lab had examined 163 of Mallon’s fecal specimens and found 120 positive for typhoid bacteria. Because of the enormous amount of germs in her body and her occupation as a cook, the Department contended that she must not be released. She “would be a dangerous person and a constant menace to the public health.”

The Department’s attorney quoted from New York State laws, arguing that the Board of Health had the legal right to quarantine sick people. It did not need to obtain a court’s permission when it was acting to prevent the spread of contagious diseases.

Mallon’s lawyer, George O’Neill, asked for her release. “Mary Mallon is in perfect physical condition,” he claimed. As evidence, O’Neill presented the reports from Ferguson Laboratories confirming that she was not giving off typhoid bacteria.

In the laboratory’s final report on April 30, 1909, owner George Ferguson wrote: “I would state that none of the specimens submitted by you, of urine and feces, have shown Typhoid colonies.” This, said O’Neill, proved that Mary Mallon “is not in any way or any degree a menace to the community.”

The attorneys had made their arguments, and the case was in the hands of the justice. Until he made his decision, Mallon could do nothing but wait in her cottage facing the East River and wonder: would she ever be set free?