11

ISLAND EXILE

“It probably means exile for life.” —S. S. Goldwater

Eight years before, Mary Mallon fought like a lion when Josephine Baker cornered her at the Park Avenue brownstone. Now she gave up without a struggle. She climbed into the car with the health department doctor, and by the end of that day, she was back on North Brother Island.

This time, Mary had no lawyer to help her. George O’Neill had died of tuberculosis three months earlier. Her boyfriend, Briehof, was gone, too, dead of heart disease. Mary Mallon was alone.

Four days later, on March 30, 1915, the New York City Board of Health “approved the indefinite detention of ‘ Typhoid Mary’ until such time as she should be declared no longer a public menace.”

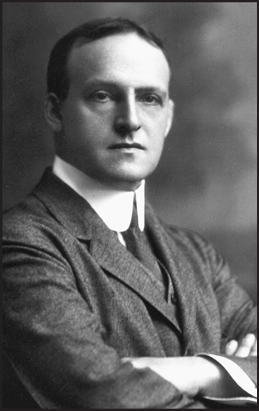

“It probably means exile for life,” said Health Commissioner Sigismund S. Goldwater, who had taken over the position in February 1914. The health department had trusted Mallon to stop spreading her typhoid bacteria. She intentionally broke her promise, and now two people were dead.

In Josephine Baker’s view, that was why the health department had to take her into custody again. “Mary … couldn’t be trusted … It was her own bad behavior that inevitably led to her doom.”

George Soper agreed with the Board of Health’s decision. “She was known wilfully and deliberately to have taken desperate chances with human life,” he wrote. Mary was once considered an “innocent victim of an infected condition,” but no longer. “She was a dangerous character and must be treated accordingly.”

A WITCH!

The sympathy that people once felt toward Mallon evaporated. The New York Tribune said that she had been given her freedom and “she deliberately elected to throw it away.” One newspaper columnist declared: “The result of Typhoid Mary’s excursion was disastrous …. There was evidently nothing to do but to shut her up and keep her out of mischief.”

To many, Mary Mallon was a despicable source of germs and death. New York’s Sun said of her: “Mary’s presence in a community means serious illness, perhaps death.” There was no excuse for her behavior: “This woman and other typhoid carriers … distribute [the germs] with their hands because they are filthy … they do not wash them when ordinary decency demands it.”

Newspapers all across the United States reacted to Mallon’s recapture. In Washington State, the Tacoma Times called her a “twentieth century witch” who “scatters GERMS—typhoid germs!”

UNSOLVED MYSTERY

Why had Mallon gone back to cooking? Maybe she didn’t see the harm in it, because she never believed that she caused the typhoid outbreaks. Perhaps she couldn’t support herself with lower-paying jobs. Or she might have been tired of the Department of Health’s control over her.

The Department tried to find out where she’d been hiding. Investigators uncovered evidence that she used the aliases Marie Breshof and Mrs. Brown to get work as a cook. They didn’t learn much else. The newspapers reported that she worked throughout the New York City area in hotels, restaurants, private homes, a sanatorium, and a rooming house. These stories were never proved.

Only Mary knew where she had been during those five years, and she never told.

Altogether, she was definitely linked to 49 typhoid cases and 3 deaths. Soper produced evidence that she caused 24 typhoid cases, including 1 death, from 1900 to 1907. In several of his writings, he said that there had been 2 more cases, although he gave no proof or details of them. The outbreak at the Sloane Hospital for Women in 1915 involved 25 cases, including 2 deaths.

The health department wasn’t certain how many other people Mallon might have infected. No one knew where she’d worked before George Soper picked up her trail. He hadn’t been able to track everywhere she’d cooked between 1897 and 1907. Some reports claimed that while she was free from 1910 to 1915, she infected at least 6 people, but that was never verified.

It is likely that Mary Mallon triggered typhoid outbreaks that nobody ever connected to her, but probably not as many as some people claimed. According to rumors, she was behind the epidemic of 1,350 cases in Ithaca, New York, in 1903, which George Soper had investigated. That wasn’t true.

Mallon’s past would remain a mystery. Her future, however, was determined the day she walked out of the bathroom of the house in Queens and into the health department car. Mary Mallon would live the rest of her life on North Brother Island.

After returning to her tiny cottage in March 1915, she settled back into her routine on the Island. She had no choice. Mallon adopted another dog to keep her company. She cooked for herself, sewed, and read magazines, newspapers, and books. Her favorites were the novels by Charles Dickens.

The doctors continued to test her feces for typhoid bacteria, and the results came back positive most of the time. Mallon never believed it.

People on the Island learned to tread lightly with her. “She knew how to throw herself into a state of almost pathological anger,” the superintendent of Riverside Hospital later said. For several years she was like a “moody, caged jungle cat.”

THE CARRIER LIST

Newspaper stories about Typhoid Mary had made New Yorkers anxious. If someone who looked perfectly healthy could spread death, were they safe in hospitals, in restaurants, and even in their own homes?

After Mallon’s recapture, Commissioner Goldwater reassured the public that the Department of Health was watching for typhoid carriers. Food handlers had to submit a feces sample for laboratory tests before the city allowed them to work. The Department investigated all outbreaks and monitored people after they recovered from a typhoid bout.

Everyone who was shedding typhoid bacteria had to report regularly for tests. These people were banned from jobs where they might infect others. If carriers were careful about personal hygiene, Goldwater explained, they wouldn’t spread the bacteria.

George Soper offered an extra piece of advice for carriers. “They must try to give up the senseless habit of shaking hands.” He told a reporter, “The germs do not fly through the air; they are transmitted by the hands.”

The Department of Health maintained a list of typhoid carriers, and it grew longer each year. In 1908, the list contained 5 names, including Mallon’s. By 1915, when she returned to North Brother Island, the Department was keeping its eye on 23 people. In 1918, the number had increased to 70. Officials used a map of the city to show where each carrier lived, in case an outbreak occurred in the neighborhood.

The health department didn’t always isolate a carrier in a hospital the way it had when Mallon was first captured. If officials were satisfied that the person was practicing proper hygiene and staying away from food-handling jobs, he or she was allowed to go free.

Carriers who did not cooperate were held in city hospitals, including Riverside on North Brother Island. The stay was usually temporary. The health department let a carrier go once the bacteria had disappeared from his or her body or when officials trusted the person to follow the rules.

Mary Mallon never received the same treatment, even though she likely sickened fewer people than several other carriers did (see sidebar, page 130). It was her bad luck to have been America’s first healthy typhoid carrier.

When George Soper found her in 1907, officials hadn’t figured out what to do with a carrier. In 1915, when they sent her back to the Island, it might have been to set an example to other carriers who considered disobeying the rules. And after all the publicity about her, nervous New Yorkers would probably have protested if she had been freed. Officials—and the public—couldn’t trust a woman who refused to believe that she spread deadly bacteria.

ON THE WAY DOWN

At the end of World War I, in 1918, typhoid fever was still a major cause of death—fifth among infectious diseases, behind tuberculosis, pneumonia, infant diarrhea, and diphtheria. But the rates of infection and death were rapidly going down.

In New York City in 1919, just 854 cases were reported to the Department of Health, almost 400 fewer than the year before. Of those, 121 people died. The Department’s investigations revealed that the majority of cases were from direct contact with a typhoid patient or through food contaminated by a carrier. Few were due to polluted water or milk. The efforts to clean up drinking water, improve sewage disposal, and pasteurize milk had made the difference.

Between 1900 and 1920, the number of Americans who developed typhoid fever dropped from about 400,000 to 35,000. Deaths decreased from 35,000 to fewer than 7,000. The doctors, scientists, and engineers involved in public health finally had reason to be optimistic about controlling the lethal disease.

A NEW LIFE

In 1918, after three years back on the Island, Mary Mallon’s life took a turn for the better. New York State began to financially support carriers banned from food handling. Mallon was given a job as a helper in the Riverside Hospital. She liked earning money again.

A few years later, a young female doctor trained her to be an assistant in the hospital’s laboratory, performing simple tests and preparing slides. Mallon became interested enough in the work to read about laboratory techniques in books that she found at the hospital.

Also in 1918, officials decided to let Mallon take day trips off the Island. Crossing the East River on the ferry, she visited people she knew in New York City, including old friends from before her capture. She never again tried to run away from the health department.

Eventually, Mallon accepted that the Island would be her home forever. She formed friendships with nurses, doctors, and other workers on the Island. The priests from St. Luke’s Roman Catholic Church in the Bronx across the river visited her.

They all knew never to mention typhoid fever or ask Mallon about her past. She remained bitter about the way she had been treated by the health department, the city, and the public.

Mallon never allowed doctors to operate on her gallbladder. It turned out to be the right decision. The health department later studied five carriers whose gallbladders were removed. In 1921, it announced that none of the surgeries had successfully eliminated the typhoid bacteria.

As the years passed, Mallon put on weight and her vision declined until she needed eyeglasses. Soon after she turned sixty, her beloved dog died. She buried him on the island, and his absence made her life lonelier.

One December day in 1932, Mallon didn’t show up as usual at the hospital lab. A concerned co-worker walked to Mallon’s cottage to check on her. Mary lay on the floor, partially paralyzed. The sixty-three-year-old woman had had a stroke.

Mary Mallon would never walk again nor return to her cottage overlooking the East River. For the next six years, she was a patient at Riverside Hospital, bound to a wheelchair or bed and dependent on the care of the medical staff. She suffered from heart and kidney disease, and her health steadily declined.

MERCY

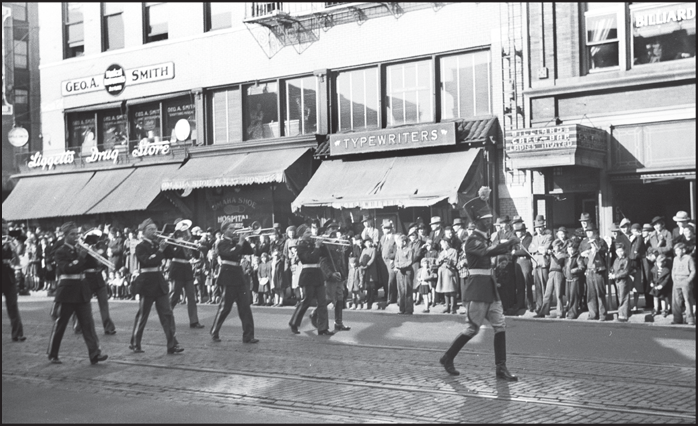

November 11, 1938, was a bright, clear day and unusually warm for late fall in New York City. At 11 a.m., four Boy Scout buglers blew taps in Times Square. All traffic stopped. In New York and across the country, Americans paused for two minutes of silence to remember the end of the devastating world war exactly twenty years before.

For the first time, the United States marked Armistice Day as a legal holiday. Government offices, schools, banks, and many businesses closed. Throughout the day, parades and religious services honored the soldiers who had fought and given their lives for the nation.

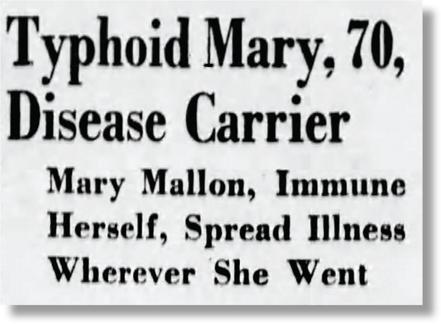

On North Brother Island in the East River, Mary Mallon died of pneumonia at age sixty-nine.

The next morning, a priest conducted her funeral at St. Luke’s. Fewer than a dozen friends and their families attended, including a nurse, the doctor who trained her to work in the hospital’s laboratory, and a friend Mallon had known since her days of freedom.

Mallon had saved much of the money she earned at Riverside Hospital. In her will, she gave a total of about $4,000 to those friends who stood by her at the end, to the Catholic Charities organization, and to a priest who often visited her. She also left money to pay for her burial in St. Raymond’s Cemetery in the Bronx. Typhoid Mary was put to rest under a gravestone that read “Jesus Mercy.”

Mary Mallon had been held on North Brother Island for more than twenty-six years. She shed typhoid bacteria in her feces until the end of her life. By all accounts, she never believed that she had given anyone typhoid fever.

Josephine Baker described her as “a pitiful creature who never committed a crime and yet who caused more deaths than the most desperate of killers.” She added, “I learned to like her and to respect her point of view.”

After Mallon’s death, George Soper summed up the tragedy of her life: “The world was not very kind to Mary.”

Mary Wasn’t the Only One

No one knows how many people Mary Mallon infected before the health department confined her. She probably wasn’t the most dangerous carrier.

In August 1909, a month after Mallon lost her court battle, the New York City Department of Health noticed a sudden, unusual spike in typhoid cases. Investigators discovered that victims in one area of the city had consumed milk delivered from a town in upstate New York. The Department immediately stopped shipments from the supplier.

Next, they searched for the typhoid source in that upstate community. After interviewing local doctors and milk suppliers, investigators identified the typhoid carrier as a sixty-one-year-old dairy farmer. The man remembered having typhoid fever forty-six years earlier. Tests showed that his feces continued to teem with the bacteria. Over the years, many of his family members and townspeople had developed typhoid, but the disease was so common in the area that nobody had ever tried to track down the source.

The health department believed that the farmer infected about 400 people in his town and in New York City during the 1909 outbreak. The man had no idea that he had caused so many illnesses. He stopped working around milk and died two years later from a heart condition.

In December 1910, during Mallon’s five-year freedom, the New York State Department of Health learned of an outbreak of 36 typhoid cases and 2 deaths. The Department traced the source to a summer guide in the Adirondack Mountain region. The man, nicknamed “Typhoid John,” was healthy, but his feces were full of typhoid bacteria.

“John” agreed to follow treatments that doctors thought might rid his body of the bacteria, and he was not locked up. Whether the treatments worked on John is lost to history.

In 1915, the year Mary Mallon returned to North Brother Island, the New York City Department of Health discovered an outbreak in Brooklyn. Ice cream sold at a sweetshop had infected 59 people. Laboratory tests showed that the owner, Frederick Moersch, was the carrier, and the Department barred him from serving food. He wasn’t quarantined, perhaps because he was supporting four children and promised to work as a plumber. In 1928, investigators on the trail of a Manhattan outbreak found Moersch making ice cream again. This time, he had sickened dozens of people.

After his second offense, Moersch ended up in Riverside Hospital, where he stayed for several years and had a job as a hospital worker. The health department attributed at least 144 cases and 6 deaths to him. Unlike Mary Mallon, Moersch eventually left North Brother Island. It’s unclear why the health department let him go. He died in 1947.

In another case from the 1920s, a carrier who worked in food service infected 87 people, 2 of whom died. Tony Labella was allowed to go free after he promised to stop handling food for others and to regularly report to the health department. But the thirty-four-year-old man disappeared.

In 1922, New Jersey officials traced Labella to an epidemic of 35 cases and 3 deaths. He had broken his promise and was working on farms. The New York authorities did not lock him up. Instead, the city found him a job as a construction worker.

Although men were connected to these outbreaks, about 75 percent of carriers are women. During this period, the majority of women did not work outside their homes and, therefore, did not trigger large outbreaks that caught the attention of the health department.

In 1938, the year Mary Mallon died, New York City’s list of healthy typhoid carriers contained about 400 names. Some of them had disappeared. Mallon was the only one held captive.