12

THE REST OF THE STORY

“Typhoid fever can be prevented.” —Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Mary Mallon despised her nickname, but that is how the world remembers her. After more than a hundred years, the name “Typhoid Mary” still describes a person who spreads disease and death yet is immune to the danger.

Typhoid Mary has become the subject of myths, novels, and plays. Rock bands and a comic book supervillain are named after her. Mary Mallon made her mark on history and culture, although few people know anything about the woman behind the name.

She is remembered for the number of victims she infected. But Mary was herself a victim of the lethal typhoid bacterium. Even though Salmonella Typhi didn’t make her sick or kill her, it ruined her life.

THE GERM FIGHTER

George Soper wrote several articles and gave numerous interviews about how he tracked down Mary Mallon. These were published during her lifetime as well as after her death.

Soper enjoyed a long career as a sanitation engineer in New York, working for the city and as a private consultant. When the New York City subway opened in 1904, Soper investigated sanitation issues, such as bacteria levels, temperatures, and air quality, in the underground trains. For several years, he led a commission that studied the sewage pollution of New York’s harbor and rivers. During World War I, Soper served as a major in the U.S. Army’s Sanitary Corps.

In 1923, he became the managing director of the American Society for the Control of Cancer, the predecessor of today’s American Cancer Society. By that time, the number of deaths from infectious diseases was rapidly decreasing. Typhoid, tuberculosis, diphtheria, cholera, and smallpox had been brought under control by vaccines, medicines, and better sanitation. As these diseases disappeared, cancer became one of the top four causes of death in the United States.

On June 17, 1948, George Soper died on Long Island, New York, at age seventy-eight after several years of illness. His obituary noted, “Dr. Soper was perhaps best known for his discovery of the famous typhoid carrier, ‘Typhoid Mary.’”

THE BABY SAVER

Josephine Baker’s career was shaped by her experiences as a medical inspector in the New York City tenements. She was appalled to find that children under age five accounted for almost 40 percent of the city’s deaths. Baker considered these deaths especially tragic because they were preventable.

In the summer of 1908, she convinced the New York City Department of Health to establish the Division of Child Hygiene, and the commissioner made her its director. The Division was the nation’s first government agency devoted exclusively to child health. It later became a model for other cities and states.

Baker’s goal was to “start babies healthy and keep them so,” and she set up programs to accomplish that. Nurses went into poor neighborhoods to check on newborns and give advice to their mothers. Baby health stations distributed safe, fresh milk and information on child care. The “Little Mothers’ League” taught girls from the tenements how to care for their younger siblings while their mothers were out working.

Baker arranged for regular inspections of school buildings to ensure that they had adequate toilets and good lighting. She stationed doctors and nurses in the schools to treat children for contagious diseases.

Josephine Baker managed to impress her male colleagues who initially balked at working for a woman. She maneuvered around the politicians who tried to interfere with her work. By 1914, she had built up the child health division to nearly 700 employees.

In 1918, during World War I, Baker told an audience that 12 percent of babies in the United States died each year. “It is three times safer to be a soldier in the trenches in this horrible war,” she said, “than to be a baby in the cradle in the United States.” She urged the country’s health departments to change this situation.

Baker left the New York City Department of Health in 1923, going on to a career in lecturing and consulting. By then, the city’s infant death rate was half what it had been in 1907 and the lowest of the country’s ten largest cities.

Recognized internationally as an expert on children’s health, Baker wrote books and magazine columns for parents as well as professional articles for doctors. She never married or had children of her own.

On February 22, 1945, Josephine Baker died of cancer in a New York hospital at age seventy-one. The New York Times credited her with making New York “one of the safest instead of the worst cities for babies to be born in.”

THE ISLAND

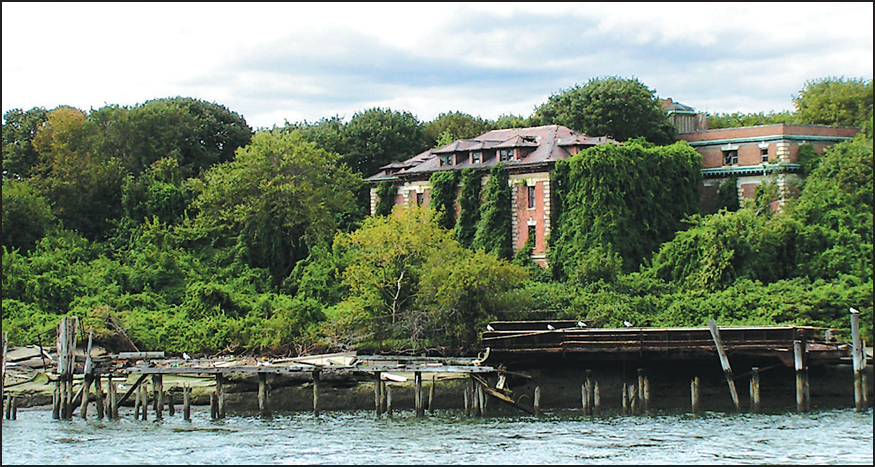

By the early 1940s, tuberculosis cases had dropped in New York because of new antibiotics, control of the disease’s spread, and healthier living conditions. The city no longer needed Riverside Hospital to treat its tuberculosis patients. At the end of World War II, North Brother Island instead became the temporary home for a group of returning soldiers and their families.

In 1951, New York State acquired the hospital, turning Riverside into a treatment and rehabilitation center for teen drug addicts. By 1963, officials decided that the center had a poor success rate in curing addicts and cost too much to maintain. That July, the Island was abandoned.

The ferry shut down, buildings crumbled, and trees and vines took over. Flocks of birds made it their home, and the city designated the Island a bird sanctuary. Today it is closed to the public.

TYPHOID IN THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY

In the United States, the public health battle against typhoid fever was a success. Water filtration, chlorination, and improved sewage disposal greatly reduced the number of victims. In 1900, about 31 of every 100,000 Americans died of typhoid fever. By 1940, the rate had dropped to only 1 out of 100,000.

Today, death from typhoid is rare. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that about 5,700 people are infected each year. Laboratory tests confirm 300 to 400 cases. Nearly two-thirds occur in just six states with large populations: California, New York, New Jersey, Illinois, Texas, and Massachusetts.

About 80 percent of these people caught the bacteria during a trip outside the country. Most had been to India, Bangladesh, or Pakistan, where the vast majority of the world’s cases occur. Parts of sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America, and south and east Asia also have high typhoid rates, particularly in urban slums.

Typhoid spreads easily where human waste contaminates drinking water and food. As many as 2.5 billion people worldwide live without basic sanitation, with a billion of them routinely defecating on open ground. Nearly 800 million have no access to clean water. In these areas, people tend to wash their hands less often and without the soap that helps remove bacteria.

International public health experts estimate that each year about 22 million people become sick with typhoid and between 200,000 and 800,000 die. But it’s not a precise count. Many victims live in developing countries that don’t monitor typhoid cases. In places without laboratory testing facilities, typhoid is often misdiagnosed (and miscounted) because its early symptoms resemble other diseases such as malaria.

VACCINE PROTECTION

Travelers to high-risk countries can protect themselves by being vaccinated. Most U.S. cases occur in travelers who had not received a vaccine before visiting these parts of the world.

The typhoid vaccine, first used in the early 1900s, has improved over the decades. Today, two types are licensed in the United States and used internationally, one taken by mouth and the other injected. In areas where typhoid fever is unusual (the United States, Canada, Japan, and Western Europe), the vaccines are given to travelers, families of carriers, and lab workers who might be exposed to the bacteria.

These vaccines are safe, though they aren’t perfect, especially for people living in high-typhoid countries. The vaccines protect less than 70 percent of those who get one, and they can’t be used on children younger than age two. Protection lasts just two to five years. Researchers are currently trying to develop better vaccines that protect a higher percentage of people for a longer time.

The existing vaccines have controlled epidemics, however. After a cyclone hit Fiji in 2010, health officials worried about a typhoid outbreak. Storm damage and flooding caused sewage to contaminate the drinking water. The islands already had one of the world’s highest rates of the disease. Seventy thousand people were vaccinated, helping to avoid a potentially devastating epidemic.

THE ANTIBIOTIC WEAPON

During the lifetimes of Mary Mallon, George Soper, and Josephine Baker, careful nursing was the only treatment or typhoid. From 10 to 30 percent of patients died. For many years, doctors experimented with various drugs, but nothing worked.

Then in 1948, researchers discovered a soil bacterium from Venezuela that destroyed Salmonella Typhi. Chemists figured out how to make a drug based on this bacterium, and it dramatically cured typhoid victims.

Today, several different antibiotics are available. With these drugs, patients rarely suffer the kind of complications that once caused death. In areas of the world where patients receive antibiotic treatment, the death rate has dropped to about 1 percent.

But Salmonella Typhi has become resistant to many of the life-saving antibiotics. In numerous countries throughout the world, people can buy them without a prescription, and the drugs have been used improperly. This has led to a growing number of typhoid cases in which the antibiotics don’t kill the bacteria. Without effective drugs to treat patients, health experts fear that the fatality rate will rise again.

OTHER TYPHOID MARYS

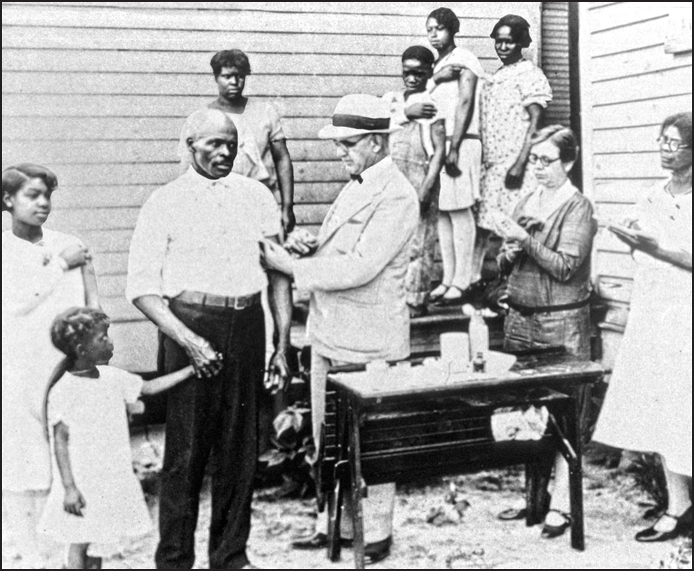

In many American communities, doctors are required by law to report typhoid fever cases to their local health department. Depending on local laws, patients may have to submit their feces and urine for testing for at least three months or until they stop shedding the bacteria. Someone who tests positive after a year is classified as a chronic carrier.

Infected people are usually allowed to go to work or school, and they’re told to wash hands carefully after using the toilet. But workers in food preparation, health care, or child care typically can’t return to their jobs until their tests are negative. In many places, chronic carriers are banned from these occupations. Local health departments often monitor carriers, making sure that they follow rules about personal hygiene and work.

The majority of carriers are cured after taking antibiotics for several weeks. When this treatment isn’t successful, the best alternative is removal of the gallbladder, where the bacteria frequently live and multiply on gallstones. The surgery is safer and more likely to cure the carrier than it was during Mary Mallon’s lifetime. But no treatment for carriers is 100 percent effective.

Health departments have extensive legal powers to protect the public from contagious diseases like typhoid. They can order testing, isolation, and treatment. The extent of a person’s right to challenge the decision in court depends on the state and the disease.

OUTBREAKS CONTINUE

Typhoid outbreaks still occasionally happen in the United States. Today’s epidemiologists trace typhoid infections to the source and find out how the bacteria spread. An outbreak usually starts with a healthy carrier preparing food, unaware that he or she is infecting others.

Sometimes, however, the source is someone with typhoid fever symptoms. In 2013, a worker in the café of a luxury department store in San Francisco was diagnosed with the disease. The health department investigation revealed that the person had been infected outside the United States.

To alert people who had eaten in the café, officials quickly issued a public statement with a list of typhoid symptoms. They advised anyone with symptoms to seek medical care, to avoid handling food and beverages for others, and to stop caring for young children and hospital patients.

Imported food has also caused outbreaks. In 2010, 12 people in three western states developed typhoid. Public health officials interviewed the victims and tested samples of foods they’d eaten.

The investigators traced the typhoid bacteria to shakes made from the frozen pulp of mamey, a tropical fruit.

The frozen mamey came from a Guatemalan factory, where it had been contaminated. The factory hadn’t properly pasteurized the pulp to kill bacteria, as required by American food regulations. Twelve years earlier, mamey from the same company caused at least 16 typhoid cases in Florida.

HOPE FOR THE FUTURE

Scientists are studying the DNA sequence of Salmonella Typhi’s genome to find weaknesses that they can use to fight typhoid fever. Clues may lead to better diagnostic tests, antibiotics, treatments, and vaccines.

Other researchers are trying to understand how typhoid bacteria remain in a carrier’s body without causing symptoms. The work is challenging because Salmonella Typhi doesn’t cause disease in other animals, and certain experiments on humans would be unethical.

Projects in developing countries are aimed at protecting the water supply from contamination and purifying it by chlorination. Unfortunately, in many parts of the world, these sanitation improvements could take years to achieve.

Someday, research and public health efforts may succeed in eradicating typhoid fever. When that happens, Salmonella Typhi will no longer inflict pain and suffering on communities the way it did in Ithaca more than a hundred years ago. And no one will ever become a “Typhoid Mary” again.

Wash Those Hands

Too many Americans don’t wash their hands after using the toilet. That’s the conclusion of recent studies conducted in public bathrooms.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends washing with soap and water for twenty seconds, about the time it takes to hum the “Happy Birthday” song twice. This prevents germs from spreading from feces and urine. To keep unwanted bacteria out of your food, wash your hands again before preparing and eating it.

Find more about when and how to wash, as well as the science behind the recommendations, at cdc.gov/handwashing.*

*Website active at time of publication.