I

Recently the National Museum of Modern Art in Tokyo published a monthly periodical titled The Modern Perspective and held an exhibition under the same name.

Looking at the periodical, I discovered that, in fact, it was about Western perspective. It seemed to be saying that the Western perspective was the modern perspective, or that the modern perspective was the Western perspective, and I couldn’t help feeling mightily displeased. I asked myself why a museum located in Japan shouldn’t advocate the Japanese way of looking at things. Why it shouldn’t show what was best about the Japanese perspective, point out what was lacking in the Western view, and indicate how the one could augment the other. Even the way in which this museum arranges artworks for display is frequently merely an exercise in copying Western fads. There is a lack of imagination.

Though I am ill in bed at the moment, I decided to write something about this periodical and lodge a protest. I couldn’t help feeling that Japan should have more confidence in the Japanese way of perceiving things, and that it should make this more widely known to the world. While there is no need to be foolishly pompous or self-aggrandizing, the time has come, I believe, for Japan to confidently present its own view. Do people think the Japanese perspective less sensitive than the Western? Do they feel that Japan should humble itself as being retrograde and less than modern? In my opinion, the Japanese way of perceiving things is richly endowed with many profound, insightful aspects that are not fully developed in the West. And this aesthetic is not composed of makeshift elements cobbled together on the spur of the moment.

Japan has learned many things from the West, beginning in the Meiji period in the mid-19th century, and there is undoubtedly still much to learn. This applies especially to science, a field in which Asia has fallen behind. Of course, if we succumb to the fallacy of thinking that science is almighty, we may lose more than we gain. There are many instances where the riches of mechanized civilization have had adverse effects and deserve careful consideration and thought. The United States is perhaps the most outstanding example of a mechanized country, but still many of its citizens are suffering from stress and feelings of angst. The fact that tranquillizers are in such demand there is a reflection of social disease. As rich as it is, America is perhaps unrivalled for its vulgar lack of propriety and decorum, which may account for its having the world’s highest crime rate.

It is fine to learn what one can from abroad, but by taking it to the point of idolization and adulation, Japan runs the risk of losing its cultural identity. It is fine to speak with pride of having a modern outlook, but if this simply means borrowing a Western perspective, there could be nothing more pathetic. Why does everything ‘modern’ have to be seen through Western eyes? At this rate, what is Asia’s raison d’être, what is its justification for being? Does Japan have to live constantly in emulation of others? No, not at all. A century has passed since the Meiji period, and it is about time Japan divested itself of Western hero worship and began returning some of what it has received. To my way of thinking, this can be done in two major ways: one is through the teachings of Mahayana Buddhism, the other through the special qualities of Asian art. In neither realm has the West shown much sign of development.

A remarkable recent phenomenon has been the interest taken in Zen Buddhism by Western philosophers. Just lately I read the following, the words of a preeminent modern Western thinker, Martin Heidegger. He said, ‘If I had come into contact with the works of Daisetsu Suzuki on Zen at an earlier date, I could have reached my present conclusions much sooner’. In addition to Zen, there is also the thought of the Kegon school and the concept of tariki (the ‘power of the other’), both of which would be innovative concepts for Christian countries. In the realm of the arts and crafts, the art of empty space seen in the Nanga school of monochrome painting and the abstract, free-flowing art of calligraphy have already begun to exert considerable influence on the West. Just as occurred in the case of the Chinese sculpture of the Tang and the Six Dynasties, the profundity of the art of Asia will inevitably receive greater recognition. Even now, Chinese pottery produced by the Song kilns is avidly collected and studied by Western museums.

Asian art represents a latent treasure trove of immense and wide-reaching value for the future, and that is precisely because it presents a sharp contrast to Western art. For example, compare Rodin’s The Thinker with the statues of the Miroku bodhisattvas at Chugu-ji and Koryu-ji, which present these differences so clearly. Even though they are somewhat similar in form, the contrast between agonized thought and quiet meditation couldn’t be more pronounced. Both are transfused with deep meaning, but The Thinker gives no indication of the final end of humankind as do the Buddhist statues. It is the principle of quietude seen in the Mirokus that Westerners should reflect upon.

II

So what does Japan have to offer the world from its corner of Asia? There are many aspects to this question, but in my opinion the most significant offering we can make is the Japanese aesthetic, its eye for beauty backed by a long history of development. This ability to see through to the underlying beauty of things should receive much more attention.

Generally speaking, the Western perception of art has its roots in Greece. For a long time its goal was perfection, which is particularly noticeable in Greek sculpture. This was in keeping with Western scientific thinking; there are no painters like Andrea Mantegna in the East. I am tempted to call such art ‘the art of even numbers’. In contrast to this, what the Japanese eye sought was the beauty of imperfection, which I would call ‘the art of odd numbers’. No other country has pursued the art of imperfection as eagerly as Japan.

I once read a discourse on art by Wassily Kandinsky in which he took a highly favourable interest in the Japanese word e-soragoto (‘art [picture] is fantasy’). The word refers to the quest for truth that goes beyond truth; it refers to the art of imperfection, the art of odd numbers.

This Japanese perspective first began to take conscious form in the Muromachi period (ca. 1336–1573) with the advent of Noh drama and the tea ceremony. Of course, the tea ceremony has its critics, and some even go so far as to say that tea is an old, musty way of thinking. But, in fact, as a highly original ‘path’ to art appreciation, it contains much that is profoundly original. Even in global terms it represents a rare way of perceiving beauty, has deeply influenced the life of the entire Japanese nation, and forms the aesthetic foundation for all Japanese today. It cannot be denied that, to one extent or another, our aesthetic education owes much to tea.

Just as Western art and architecture owe much to the sponsorship of the House of Medici during the Reformation, tea and Noh owe much to the protection of the shogun Ashikaga Yoshimasa (1436–90). Yoshimasa may not have been an astute politician, but he loved art passionately. It was he, together with the Ami family of artists and the tea master Juko (?–1502) working under his protection, who created perhaps the most brilliant era of Japanese culture, the Higashiyama period (1443–90). Later, the tea masters Joo (1502–55) and Insetsu (dates unknown) also played an important role. In the background Zen priests such as Ikkyu Sojun (1394–1481) were active, giving tea a more profound Buddhist base. This led to the phrase ‘Zen and tea are one’, indicating how tightly Zen and the tea ceremony were bound together – probably the first time in world history that art appreciation and religious thinking were so intimately interfused.

III

What, then, was the fundamental principle underlying the beauty of tea (chabi)? As fortune would have it, it was not an intellectual concept, but rather consisted of concrete objects that acted as intermediaries – the teahouse, the garden path, the utensils. It was these that allowed the tea masters to plumb the depths of beauty. Concepts such as wabi and sabi had appeared in the previous period in reference to literature, but with the flourishing of the tea ceremony they began to be used in reference to concrete objects. Literally, sabi commonly means ‘loneliness’, but as a Buddhist term it originally referred to the cessation of attachment. The ultimate Buddhist goal was the achievement of the fourth Dharma seal – ‘Nirvana is true peace’ – through the cessation of self, the cessation of greed, and the superseding of dualism. Ultimately, the beauty of tea is the beauty of sabi. It might also be called the beauty of poverty – or in our day it might simply be called the beauty of simplicity. The tea masters familiar with this beauty were called sukisha – ki meaning ‘lacking’. The sukisha were masters of enjoying what was lacking.

Thus the beauty of tea was not the pursuit of unerring perfection. In fact, Tenshin Okakura (1862–1913) called it the beauty of imperfection. Shin’ichi Hisamatsu (1889–1980) went a step further and called it the rejection of perfection. But I think it goes beyond the dualistic thinking of perfection or imperfection; borrowing from Zen terminology, I would call it natural (buji) beauty, the beauty of everyday life (byojotei), of egoless freedom (muge). It is not a clinging to the duality of imperfection or perfection; it is the beauty of absolute freedom.

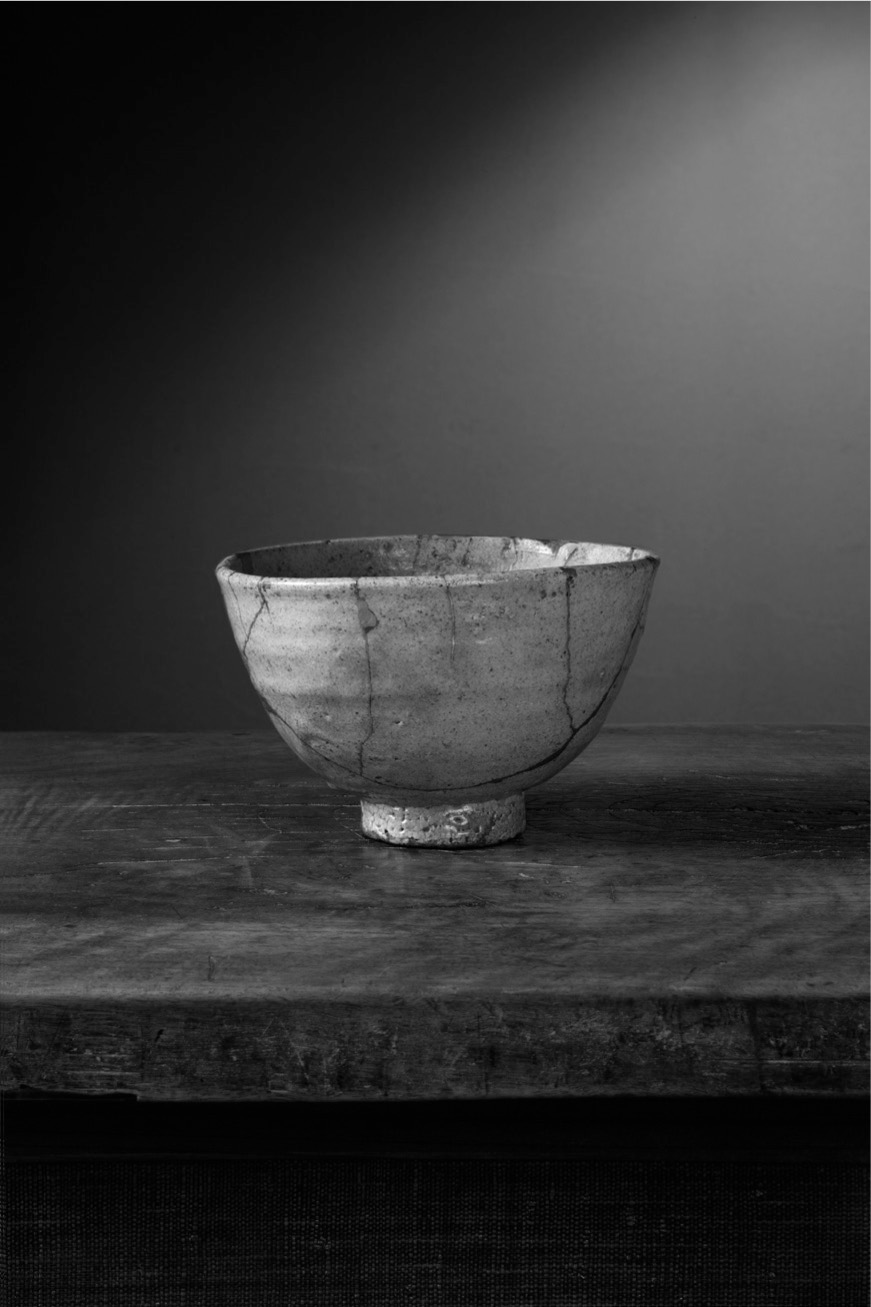

While imperfection in the form of deformation can often be seen in tea bowls and other utensils, this is not an intentional distortion but an expression of the love of unhindered freedom. There is no true deformation that does not follow the laws of necessity. In later years, when deformation came to be consciously created, when the rejection of perfection became a matter of deliberate manipulation, the true meaning of tea began to be lost. As I see it, the true path came to an end with Joo, and by the time of Sen no Rikyu (1522–91) and his style, tea had come to be categorized into a number of fixed formulas, marking the onset of its downfall. By clinging unwaveringly to the forms of tea, the freedom of tea was lost. True tea must be selfless tea (cha misho). To put it in somewhat contradictory terms, true tea existed only before the advent of the tea ceremony. After the coming of tea, when deformation came to be consciously sought, common everyday beauty disappeared and unnatural manipulation began. This meant the demise of the beauty of tea. In the recent West, potters have been avidly pursuing ‘free form’, which in actual fact is nothing more than a regurgitation of post-tea manipulation. There is no way this will produce true freedom. What the Japanese perspective sought was natural beauty; nothing more, nothing less. No matter where you look abroad, you will find nothing comparable. In modern Western art there is now a strong tendency to seek the strange and extraordinary. But it lacks a sense of solid significance; there is something pathetic about it, something painful and distressed. This is a result of a penchant for the diseased and perverted, not for the wholesome and healthy.

IV

Here I would like to say a word about the character of tea utensils. As I wrote above, tea is not repelled by cracking and distortion but rather sees them as a new source of beauty, an expression of freedom. Nowadays, the West has become very conscious of deformation, and almost all of its modern art intentionally incorporates it in some form or another. Yet this same deformation has been a part of the art of tea for over 400 years. This Japanese perspective, which doesn’t hesitate to find beauty even in cracked ware, is without parallel anywhere in the world.

Of course, if this is taken to an extreme, the ordinary form of an object will be violated and the original meaning lost. It is said that tea masters would sometimes break a bowl on purpose and then have fun mending it. This is going a bit too far, I think, even though it is a result of the tea masters’ insight into the nature of beauty. It might be seen as a deleterious effect of this perspective and something to be guarded against. Nevertheless, it was the tea masters who first discovered the beauty of deformation, and they are to be honoured for their originality and insight. This tradition is still ingrained in the Japanese eye for beauty, permeating the Japanese soul after decades of training. It is an appreciation of art that is free and unhampered. Deformation represents a quest for beauty that goes beyond the limitation of fixed forms.

I have many friends, but for quickness of perception my Japanese friends generally stand out head and shoulders above the rest. Even among young Japanese there are some with very keen eyes. Bernard Leach (1887–1979) once had this to say: ‘If you find something good in a Japanese secondhand utensils shop, you have to buy it immediately, because if you go back the next day, it will be gone’. He was expressing his admiration for the quickness and perception of the Japanese eye. In Britain it seems the shop would be visited a number of times before a decision was made. This is not bad, but it shows the extent to which Japanese quickness is acknowledged. While not always perfectly logical, perhaps the Japanese make up for this failing in their daily lives by keen intuition.

Next I would like to take up what it means to ‘see’. While everyone, of course, sees, there are many ways of seeing, so that what is seen is not always the same. What is the proper way of seeing? In brief, it is to see things as they are. However, very few people possess this purity of sight. That is, such people are not seeing things as they are, but are influenced by preconceptions. ‘Knowing’ has been added to the process of ‘seeing’.

We see something as good because it is famous; we are influenced by reputation; we are swayed by ideological concerns; or we see based on our limited experience. We can’t see things as they are. To see things in all their purity is generally referred to as intuition. Intuition means that things are seen directly, without intermediaries between the seeing and the seen; things are comprehended immediately and directly. Yet something as simple as this is not easy to do. We mostly see the world through tinted glasses, through biased eyes, or we measure things by some conceptual yardstick. All we have to do is look and see, but our thinking stands in the way. We can’t see things directly; we can’t see things as they are. Because of our sunglasses, the colour of things changes. Something stands between our eyes and things. This is not intuition. Intuition means to see immediately, directly. Something we saw yesterday can no longer be seen directly; it has already become a secondhand experience. Intuition means to see now, straight and true; nothing more or less. Since this means seeing things right in front of you without intermediaries, it could be called ‘just seeing’. This is the commonsensical role of intuition. In Zen terms it might be expressed by the saying, ‘One receives with an empty hand’.

Considered as a form of activity, the seeing eye and the seen object are one, not two. One is embedded in the other. People who know with the intellect before seeing with the eyes cannot be said to be truly seeing. This is because they cannot penetrate beyond the ken of the intellect and achieve perfect perception. There is a huge difference between intellectual knowledge and direct intuition.

With intuition, time is not a factor. It takes place immediately, so there is no hesitation. It is instantaneous. Since there is no hesitation, intuition doesn’t harbour doubt. It is accompanied by conviction. Seeing and believing are close brothers.

In the realm of seeing intuitively, the Japanese are particularly blessed. This is due, as mentioned above, to the nationwide education afforded by the tea ceremony. Every country, according to its historical and geographical conditions, has its own peculiar character. India is characterized by intellect, China by ready action, and Japan by aesthetic perception – the three splendours of the East. Indians are adept at thinking, Chinese at acting, and Japanese at appreciating art. In Europe, France is close to Japan, Judaism to China, and Germany to India. In Germany, however, the intellect tends to be philosophical rather than religious.

While there may be many intrinsic contradictions, I still think that there is probably no country like Japan whose people live in surroundings composed of specially chosen objects. Behind it all is undoubtedly some sort of educated taste or standard of beauty. Of course, some aspects may be shallow or mistaken, but in any case things are chosen according to some standard. This may be something as simple as shibui or shibumi (simple, subtle, and unobtrusive beauty), a concept which has permeated all levels of Japanese society. It is hard to tell to what extent this simple word has safely guided the Japanese people to the heights and depths of beauty. It is astonishing, in fact, that a whole nation should possess the same standard vocabulary for deciding what is beautiful. This is due entirely to the laudable achievements of the way of tea. Even people of the flashiest sort know in the back of their mind that shibumi is a class above them; they may even feel that, as they grow older, they themselves will one day join its ranks. Among the recent seekers after the new and novel, there are those who consider shibumi to be old and out-of-date; this is not a fault of shibumi, however, but just a matter of personal preference.

Shibumi is not wandering or drifting between the new times and the old. It contains something that resides outside of time, a truth that is always new and fresh. It harbours a deep Zen significance. It represents a natural beauty that the Rinzai sect of Zen described with the word buji. Since it is not a fabricated beauty, it is not lost in the comings and goings of ephemeral fads. The Japanese sense of beauty is bolstered by a profound backdrop, something not to be found in the West. Without doubt it will contribute to new cultural developments in the future, for it has the power to augment the failings of Western culture. The Japanese people should take pride in their aesthetic eye and make it more widely known. It is worth noting that, even in the East, Japan is the only country possessing a standard aesthetic vocabulary consisting of terms like shibumi. In the realm of aesthetic appreciation, even China and Korea lag behind. One might go so far as to say that the true appreciation of the art of Japan’s two great Asian predecessors is best done by the Japanese. Strangely, the ones to first seriously study Korean art and realize its great value were Japanese, not Koreans. Here we can see the workings of the Japanese eye. For that reason, Japanese museums should play a more active role in highlighting Japanese taste. This can be easily done without borrowing Western perspectives. Furthermore, the artistic displays should be carried out according to Japanese principles. If this is done, the eyes of the world will be struck with amazement.

In a very small way the Japan Folk Crafts Museum has been trying to fulfil this mission, to unreservedly highlight the Japanese aesthetic perspective. There is no blindly following Western ways. There is no being led astray by ‘modern’ perspective. In consequence, there is an endless stream of foreign visitors. In fact, I should like to see the Japanese eye be elevated to the level of an ‘eternal’ eye. This is not impossible. There is no need for the Japanese eye to pursue fads or fashion. It is deeply rooted in Buddhist thinking and represents an intuitive quest for the truth. If circumstances permitted, I would one day like to build a museum in the West arranged on Japanese principles. To bring the Japanese perspective into the light of the world is, I believe, a cultural mission that we cannot ignore.

V

Above I discussed the insights inherent to the Japanese perspective by referring to the art of odd numbers. Here I would like to say something about the beauty of muji (‘no ground’). Muji essentially means a ground that is plain, solid-coloured, and unpatterned. There is virtually no tradition in the West to revere such beauty. In ceramics, for example, the majority of Western objects are patterned and multicoloured, with the patterns playing the most prominent role. The Japanese view, on the other hand, has largely sought the beauty of the plain and the unadorned as its ultimate goal.

This perception has its distant roots in the Buddhist precepts that all things are empty of intrinsic existence (ku) and that all is void (mu). The appreciation of muji may be simplicity itself, but at the same time it involves the highest level of sensibility. The Japanese interest in muji grew in step with the burgeoning of tea. Ultimately, wabi, sabi, and shibumi are different approaches to muji. In the field of ceramics, it hardly needs to be said that the country that has produced the greatest number of muji ceramics is Korea. This is not a result of a tradition of infusing Zen and tea as in Japan, but the outcome of Korea’s history and natural environment. The number of monochrome pieces in white or black glaze is stupendous. There are no intricate designs featuring a multitude of colours. From the beginning, Korean ceramics seem to have been fated to be detached from the world of colour. The same is true of Korean textiles, which are undyed. Everyone wears white clothing. Koreans don’t even have the custom of enjoying colourful flower arrangements or toys. However, it would be superficial to think of muji as simply a lack of colour. Rather it is an expression of the limitless existence (yu) that is encompassed by the void of mu. In terms of Noh theatre, it is movement within quietude, quietude within movement. It is an example of the infinite riches to be found in a life of honest poverty. Or it is a concrete representation of ‘Emptiness exactly is substance’ from the Heart Sutra. While Japanese love muji pottery, the West has no particular fondness for unglazed ware or its close equivalents. Those who love tea bowls will automatically turn over the bowl to check its raised foot, which is generally unglazed and rough, revealing the texture of the clay. It is a source of unrivalled pleasure. This holds especially true for areas where the glaze is thin and uneven, which are called kairagi (‘sharkskin’). This type of appreciative assessment is unknown in the West. One of the principles of tea propounds the value of roughness as well as quiet appreciation. ‘Roughness’ refers to naked and raw places without glaze or sheen, which are perceived as overflowing with flavourful subtlety. Here we can see the insight and profundity of the Japanese eye for beauty. Here is the reason tea masters valued Bizen and Iga ware so highly. They represent a kind of naked beauty, a beauty without artifice. This lack of glaze and sheen also accounts for the appeal that 17th-century foreign namban pottery held for the Japanese. Interestingly enough, even as much as 200 years ago, the beauty of Bellarmine stoneware was highly appreciated in Japan.

The keen attention given plain muji ware is one of the characteristics of the Japanese perspective. It is not an exceptional case, however, but inherent and fundamental. Someday Western students of art will come to realize this. It could be expressed by saying that the plain is the best. There is also the Zen saying, ‘The inelegant is also the elegant’. In the plainness of muji can be seen an infinite variety of patterns; ‘plain’ does not mean that nothing is there. Here I would like to append three lines in praise of muji.

A pattern that is not a pattern is a true pattern.

Create patterns until they are no longer patterns.

The true pattern is a patternless pattern.

When creating a pattern, one’s heart must also be muji. A pattern must be followed through until it is no longer a pattern. It is a true pattern only when it has ceased to be a pattern. Forgetting the void of mu and lingering in the world of existence (yu) will not produce profundity.

Among tea utensils, Karatsu ware is revered for its simplicity of design, a lingering sense of muji. On the other hand, work like that of Nonomura Ninsei (17th century), with its colour and elaborate designs, is several steps removed from the tea ideal. Tea masters were particularly fond of ‘brushed’ (hakeme) pottery, and detected in the traces of the brush an infinite subtlety. These traces might be called the quintessential muji pattern. White monochrome clay is unaffectedly applied, and the path of the brush spontaneously creates a pattern, a patternless pattern. This also accounts for the fact that the essentially plain yohen tenmoku was so widely revered; unadorned, it is infinitely adorned. Raku ware and suchlike consciously pursued this type of beauty. Of course, Raku tea bowls are largely muji, though they are given infinite variety through the use of glaze. Ido, the king of tea bowls, is without specific pattern, but it does have a rich design owing to small imperfections in the glaze, throwing, clay quality, and firing.

Notably, all the tea utensils the tea masters loved were, as a rule, of the muji type. The Asian concept of mu that gave birth to this beauty deserves to be brought to the attention of the world. Some day in the future the West will undoubtedly welcome this magnificent gift. Muji can alternatively be called simplicity. In religious terms it might be likened to the virtue of honest poverty, a poverty that is replete with riches. The beauty of muji is the beauty of poverty. ‘Roughness’ and ‘quiet appreciation’ characterize this beauty.

It has not been my intention in the above to belittle the decorative nature of Western ceramics; there is much that is superlative there. From a Japanese viewpoint, however, the best Western pottery is that which contains a certain simplicity in its decorative effects. When there is an element of mu hidden within, their beauty becomes ever more profound. Flashy effects alone are not enough. Their effectiveness depends on how much mu they contain. Mu remains the most important, the deepest, the most fundamental of artistic principles. Japan should, I think, make a gift of this principle to the West. This is the heavy burden, the mission, that the beauty of mu must bear. Together with the beauty of odd numbers, it forms the bedrock of the Japanese sense of beauty. One day the West will discover the infinite originality of this principle. As a Japanese, I feel both a sense of pride and mission in bringing it to notice. All Japanese should join in this worthy endeavour.