CHAPTER ONE

The Nature of a Political Resource

“Oil” is a catch-all term that covers a diversity of liquid hydrocarbons. The starting point for most of these is “conventional” crude oil, a form of oil sufficiently liquid to be pumped directly out of the ground and rich enough in carbon–hydrogen atomic linkages to be directly refined. Conventional crude fueled the remarkable expansion of oil production and consumption during the twentieth century but growth in the last decade has stalled, and is increasingly giving way to “unconventional” sources. These are mostly hydrogen-enriched synthetic crude recovered from sand and rock containing bitumen, and liquids associated with natural gas production; together these account for 10 percent of global oil production and could rise to 30 percent by 2035. The origins of oil and the chemistry of crude formation might seem of little relevance for understanding the politics of oil. However, the conditions under which oil forms are key to understanding both the extraordinary utility that modern societies have found in oil and fundamental questions of control. They determine the character of crude, the uneven distribution of oil resources at the global scale, and the costs and risks of turning raw resources into valuable products. Oil forms via the decomposition of organic (carbon-based) matter under conditions of heat and pressure – a process akin to “slow cooking,” more properly known as “diagenesis.” Most of the oil being extracted today was formed between 200 million and 2.5 million years ago. The processes that break down organic matter and lead to the formation of oil typically occur at temperatures between 75°C and 150°C, and in most settings these conditions are found 2–3.5 kilometers below the surface. This creates an “oil window”: above it, temperatures are too low for oil to form; below it, the longer hydrocarbons are broken down into shorter chains, producing natural gas instead of oil. A particular combination of physical conditions is needed if these hydrocarbons are to concentrate together rather than simply disperse. Oil forming in an organic-rich source rock needs a porous “reservoir” rock (typically sands, sandstone, or limestone) into which it can migrate and accumulate, and an impermeable seal or cap that prevents oil from moving further. Because the conditions for the formation of oil are not found everywhere, crude oil is variable in its physical and chemical properties and unevenly distributed in the earth.1

Crude oil is primarily carbon, atoms of which are locked together with hydrogen in different arrangements to form “hydrocarbon” molecules. As with other “fossil” fuels, the carbon atoms in crude oil are an underground stock accumulated over millions of years via the global carbon cycle. Pumping, refining, and burning crude oil returns these carbon atoms to the surface – ultimately in the form of carbon dioxide emissions to the atmosphere. In this way, the global oil industry acts as a carbon conveyer, moving carbon stocks from below ground into the atmosphere. And because the rate at which carbon flows to the surface is much greater than the return flow – via the decomposition of organic matter or the deliberate capture and storage of carbon dioxide – the oil industry is deeply involved in the atmospheric accumulation of carbon dioxide and climate change.

The way in which carbon and hydrogen are combined varies, so that crude oil is made up of many different types of hydrocarbon molecules. The larger the number of carbon atoms that make up a molecule, the heavier the hydrocarbon: from gaseous methane and ethane with one and two carbon atoms respectively, through liquid gasoline with 7–10 carbon atoms per molecule, to highly viscous bitumen with more than 35. Crude oil also contains other materials, including sulfur, nitrogen, metals, and salts. Because it is a natural material that reflects the conditions of its formation, the quality of oil in underground reserves is highly variable. Among the most significant forms of variability are: density (oil with more hydrogen is lighter and has a lower specific gravity); sulfur content (a higher content characterizing “sour” from “sweet” crudes); viscosity (how readily it flows); and acidity and the presence of metals. Oil is a liquid hydrocarbon. The rather obvious fact that oil flows is significant, because – unlike gas or coal – it can be moved over distance with comparatively few energy and labor inputs. It can be pumped across continents, into storage tanks, and into engines. Underground, oil is a liquid that is often under pressure, and under the right conditions it travels to the surface without lifting. On the other hand, this flow character lends oil an unruliness – a capacity to flow beyond control – that requires capital, equipment, and skill to contain.

For thousands of years, societies have found utility in these physical and chemical properties of crude, including waterproofing for boats, as a mechanical lubricant and as a medical ointment. Today, crude’s value lies in its role as a chemical feedstock and fuel. The diversity of hydrocarbon molecules – and the relative ease with which they may be split, combined, and re-engineered – provides a rich storehouse of potential petrochemical combinations with which to manufacture new materials, including plastics, synthetic fibers, and a range of chemicals. One of every 15 barrels of crude oil (i.e. 6 percent) is used in this way as a feedstock for the production of petrochemicals.

It is as a fuel, however, that most crude oil is used. Combining hydrocarbon molecules with oxygen – as in combustion – releases large amounts of energy as heat and light. Oil packs a greater energy punch than coal or natural gas: nearly twice as much as coal by weight, and around 50 percent more than liquefied natural gas by volume. The practical effect of this greater “energy density” is that oil has unrivaled capacities as a transportation fuel. The amount of oil required to move a ton or travel a thousand kilometers is less than for other fuels, allowing expanded mobility and geographical flexibility. The replacement of coal (through steam) by oil (diesel, gasoline, kerosene, and marine fuels) in transportation, which occurred for the most part in the first half of the twentieth century, reflected the greater energy services that oil could provide. The higher energy density of oil changed the economies of scale required for crossing space, allowing the size of vehicle units to fall – from the train and tram to the automobile – and an increase in the power output for a given size or weight of engine. Oil’s energy density enabled the evolution of the internal combustion engine (where oxidation/combustion on a small scale released a sufficient amount of energy to enable the direct movement of a piston), as opposed to the much larger, external combustion engines associated with steam power. Oil was not the first fossil fuel to have significantly shrunk distance: the introduction of coal-fired steamships in the second half of the nineteenth century drove down shipping costs and further facilitated long-distance trade in bulk commodities like wheat and wool. But oil consolidated this process and drove it further: from cars and airplanes, to diesel and bunker fuels for ocean shipping. In the US today, three-quarters of all petroleum is used as transportation fuel. As a fuel, oil is burned in a variety of forms. These include gasoline and jet fuel at the lighter end of the spectrum; heavier diesel fuels, heating oils, and bunker fuels for shipping; and, heaviest of all, petroleum coke which is used as a fuel in steel smelting and cement production.

Oil’s high energy density and liquid properties mean the “gap” between the amount of energy expended in gathering a barrel of oil and the amount of energy that the barrel can release can be very large. Harnessing this “energy surplus” has enabled large gains in labor productivity over the last hundred years, as oil-based machines replaced human labor and facilitated growing economies of scale. The energy surplus available through oil has enabled industrial economies to overcome declining resource quality and the exhaustion of local stocks, expanding in turn the output of food and raw materials. The average energy surplus available through oil has been declining, from around 100:1 down to 30:1 over the course of the twentieth century, with some deepwater crude and unconventional oil sources now as low as 5:1. This declining ratio demonstrates the gradual deterioration of “energy returns” as investment has increasingly become geared toward accessing harder-to-reach conventional oil deposits or hard-to-upgrade unconventional sources.2

The condition of the resource: growing uncertainty, declining quality

Over the last 150 years around 1.5 trillion barrels of oil have been extracted from the earth, over half of it since around 1989 (see Figure 1.1). At the same time, global oil reserves have grown: world reserves grew by 51 percent between 1995 and 2015 and now stand at 1.7 trillion barrels. The clue to this apparent paradox is that reserves (unlike the total planetary resource) are not fixed, but are shaped by geological knowledge, technology, political factors, and the economics of production. As oil companies probe the earth, they produce not only oil at the top of the well but also new reserves at the bottom. For most of the twentieth century, exploration activity and investment in existing fields “produced” reserves faster than they were recovered, and most of the world’s largest fields – the “supergiants” that continue to supply today’s demand – were discovered between the 1930s and 1960s. While exploration and technological change continue to “produce” reserves, there are three significant changes.

Figure 1.1 World oil production and price (1900–2015)

Source: Authors, based on data from BP Statistical Review 2016.

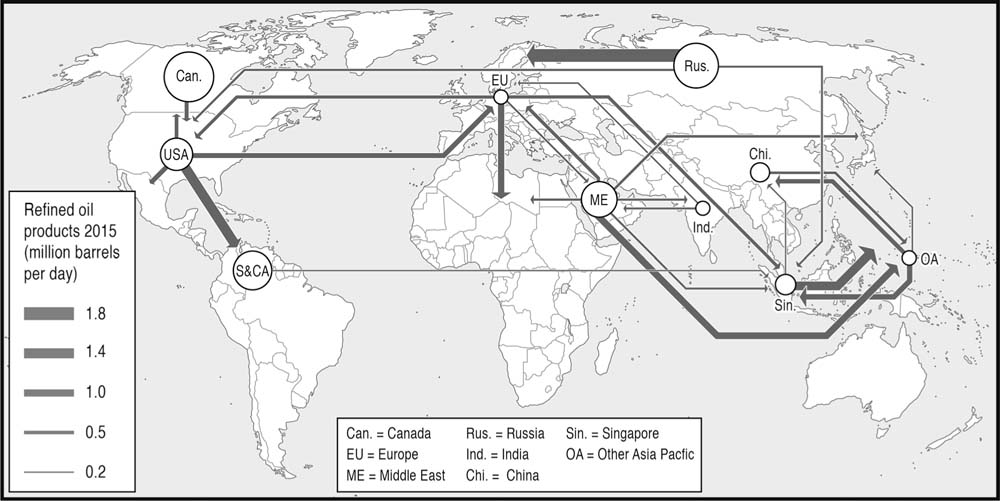

First, finding new reserves of “conventional oil” – the type of crude oil that has underpinned twentieth-century growth – is proving increasingly difficult. There have been new discoveries in Africa and Central Asia, as well as re-evaluations of reserves in Iran and Iraq. However, overall reserve growth of conventional oil has slowed to a standstill outside the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), and there is increasing uncertainty over the ability to expand production from known reserves in the Middle East. The reserves/production ratio – which captures this dynamic of depletion and replacement – reached 45 years of production by the late 1980s, but then remained relatively flat until the inclusion of Canadian and Venezuelan unconventional sources from the mid-2000s, despite a rise in the price of oil. A handful of countries control the lion’s share of the gold-standard conventional crudes that have underpinned economic growth in the twentieth century (see Table 1.1). The center of gravity of global reserves of conventional oil continues to be the Middle East with 47 percent – 800 billion barrels – of proven reserves, although its dominance has been falling (see p. 18). The future of conventional oil will remain the Middle East, but it is clouded by uncertainties over the real volume of reserves, political factors, and rising domestic oil consumption. Saudi Arabia has continued to declare about 260 billion barrels of conventional crude oil reserves since 1989 while maintaining, at times with some difficulty, production of over 11 million barrels per day (mmbd) in recent years. At 155 billion barrels, Iran supposedly holds among the world’s largest reserves and, despite doubts about many upward revisions, the recent lifting of major political constraints on production suggests much potential for growth. Iraq reassessed its reserves upward to 143 billion, assuming higher oil recovery rates. With major investments and despite a continuation of hostilities, Iraq doubled its production from 2 to about 4 mmbd between 2003 and 2015, still a far cry from the Iraqi government’s initial target of 12 mmbd by 2017. The Persian Gulf is not only a major repository of oil, but it also enjoys some of the lowest production costs and is relatively close to major markets, with Europe, India, and China all within two weeks of tanker travel or less than 6000 km of pipelines. The reserve-holding states of this region – and their custody of a high proportion of the world’s high-quality oil resources – are one of the distinctive features of the political economy of oil.3

Table 1.1 Reserves, production, and consumption, leading countries (2015)

Source: Data from BP Statistical Review 2016 (differences between consumption and production result from stock changes, non-petroleum additives and substitute fuels).

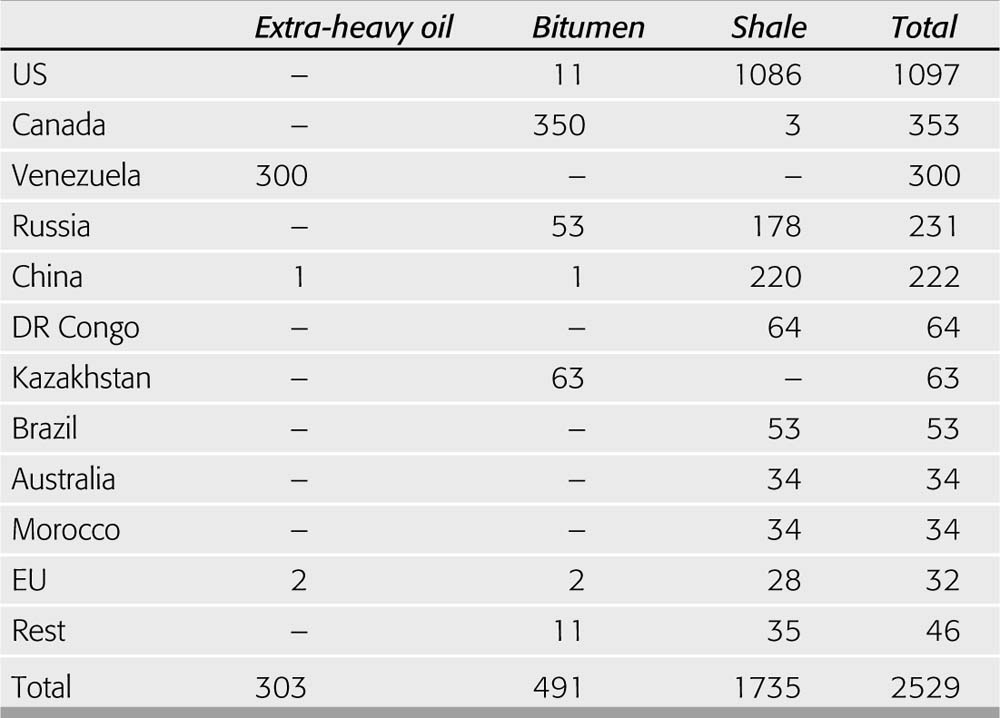

Second, the quality of reserves is changing. As the highest-value light crudes are depleted, the physical and chemical profile of reserves is shifting toward heavier, poorer-quality oils that are more costly to extract and refine and which are associated with higher greenhouse gas (GHG) and other emissions. Within the broad category of conventional oil, average sulfur content is rising as poorer-quality crudes are brought into production, and there is a shift toward heavier crudes overall to match growing oil demand. There is also a significant turn toward so-called “unconventional” sources of crude (see Box 1.1). Although these do not have the premium characteristics of conventional crude, they are expected to account for around 30 percent of consumption by 2035. The growth of unconventional reserves challenges the primacy of Saudi Arabia in global reserves, with Canada, Venezuela, and Russia holding major reserves in heavy oil and bitumen, and the US, China and Russia in shale oil (see Table 1.2). Output of shale oil in the US, also known as “tight oil” because the shale rock hosting the oil is of low permeability and the oil must be driven from the formation via hydraulic fracturing techniques, has risen rapidly from 0.5 mmbd in 2008 to 4.5 mmbd in 2015. As a consequence, the US now leads global production of unconventional oil. Shale output has doubled US oil production between 2008 and 2015, transforming it into the world’s largest oil producer (Table 1.1) and creating political conditions in which it became possible for the US Congress to lift a ban on crude oil exports introduced in 1975. ConocoPhillips and NuStar Energy shipped the first batches of crude, pumped from the Eagle Ford Shale in Texas, to Europe in January 2016 with oil producers and oil traders following suit. Tight oil production, however, can prove vulnerable to low oil prices due to high production costs and rapid well depletion associated with the very low porosity and permeability of reservoir rocks, and the need to use horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing (“fracking”) techniques. Alberta’s “tar sands” have witnessed similar growth in output, increasing from 1 mmbd in 2005 to 2.3 mmbd in 2015. However, given the capitalintensive character and high production costs of the sector, low prices have led to the suspension of many of the projects through which production was planned to grow to 4 mmbd by 2030. Venezuela’s unconventional oil production has stagnated at 0.5 mmbd and seems unlikely to reach 2 mmbd even by 2025. Because unconventional “heavy” sources of oil are essentially “undercooked” or degraded forms of conventional oil – with their long hydrocarbon molecules not having been broken down into shorter ones, or shorter molecules having been altered by bacteria and oxidation – significant inputs of energy, hydrogen (in the form of natural gas), and water are needed to both extract and upgrade them. Unconventional oil reserves are very large but the energy demands and environmental burdens are high, and decried by opponents of shale oil projects and Alberta tar sands.

Table 1.2 Unconventional oil reserves

Value represents best estimates of ultimately recoverable resources (URR) in billion (or giga) barrels.

Sources: S. H. Mohr and G. M. Evans (2010), “Long-Term Prediction of Unconventional Oil Production,” Energy Policy 38(1): 265–76; World Energy Council, 2010 Survey of Energy Resources.

Third, in the search for new reserves, the “frontier” of extraction is changing. This includes the Arctic, the ultra-deepwater environments offshore (i.e. over approximately 1,500 meters of water depth), as well as areas with limited state capacity and where the governance systems and civil society are in a fledgling condition. These “unconventional” locations are increasingly a feature of the international political economy of oil. Production from ultra-deepwater environments in Brazil, the Gulf of Mexico, and the Gulf of Guinea has been growing over the last decade. The explosion on the Deepwater Horizon drilling rig in 2010, and the subsequent uncapped flow of crude from the Macondo oil field around 1,500 meters below the sea surface, indicate the risks and challenges of sourcing supply from unconventional environments.

The production of oil is necessarily linked to reserves, but the geographies of production and reserves do not neatly map onto one another. If the development of oil followed a strictly economic logic, in which the largest, low-cost reserves were exploited preferentially, then production would converge on the comparatively low-cost reserves of the Middle East where break-even costs are lower than US$10 per barrel. Production followed this trend between 1955 and 1975 as a result of attractive economic conditions and the introduction of supertankers that drove down the cost of moving crude oil to markets. However, the nationalization of production by large resourcing-holding states during the 1960s and 1970s – and dramatic spikes in the price of oil that these states achieved through coordinated action in the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries – drove new oil-field development in the UK, Norway, Alaska, Nigeria, the Gulf of Mexico, Angola, and Russia. This pattern of geographical diversification away from the Middle East has continued with the collapse of the Soviet Union, so that the geography of production is now significantly less concentrated than that of reserves. By 2015, the Middle East accounted for 47 percent of reserves but only 32 percent of production. The development of unconventional sources continues this trend of diversification away from the Middle East, such as the 2.3 mmbd (equivalent to Qatar) currently produced from bituminous sands in Canada, or the 1 mmbd (equivalent to Oman) from the Bakken shale in North Dakota. In 2011, the president and CEO of Saudi Aramco, Khalid al-Falih, acknowledged the “more balanced geographical distribution of unconventionals” was reducing demand for growth in conventional output from the Middle East. To protect their eroding market share, OPEC members (and Saudi Arabia in particular) have maintained production rates in the face of slowing demand growth. The effect has been to push down oil prices from the middle of 2014, below the level required to keep costlier unconventional production economically sustainable. Lower prices have knocked off some “tight oil” production and led to the suspension of new bitumen projects. They have also, however, hurt the budget of OPEC regimes. Unconventional oil production is itself spatially concentrated (partly due to the geography of the resource base but also to the massive infrastructure required to upgrade unconventional sources to liquids). The further development of unconventional oil sources – particularly oil shales which are widely distributed – could, however, see this degree of concentration decline.5

The shape of demand: lighter, cleaner, Asian

Overlaid on the highly uneven geography of global oil reserves is a different pattern of industrial development and economic growth. Simply put, the centers of greatest demand for oil do not coincide with reserves. Demand varies widely among countries (and within them). The US consumes 20 percent of world production yet has only 3.2 percent of reserves and 4.4 percent of the population. Consumption is around 123 barrels per day per thousand people in Saudi Arabia, 60 in the US, 24 in the UK, 9 in China, and 0.7 in Bangladesh. For both individuals and countries, the price of oil can be an obstacle to participating in “demand.” The discrepancy between these two different geographies, between where oil is found and where it is required, underpins several significant features of the global political economy of oil as outlined below.6

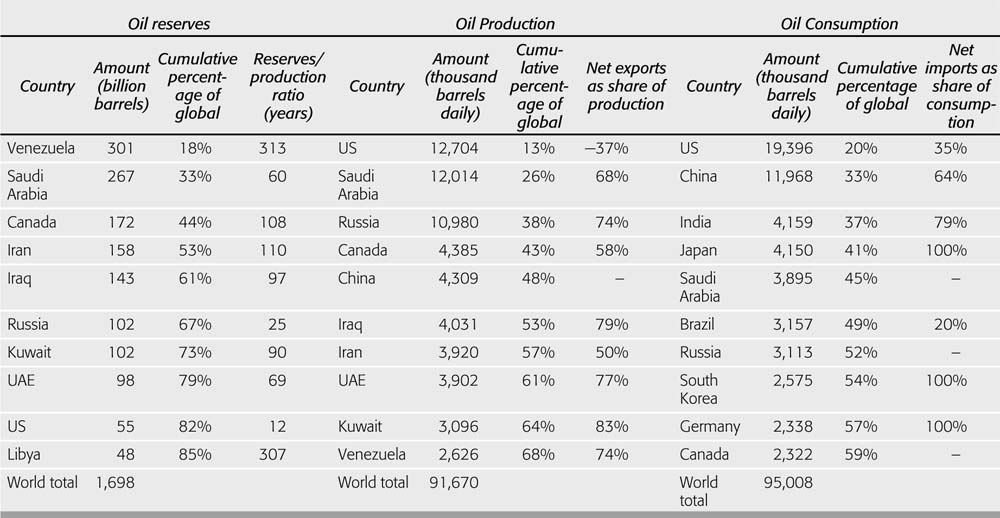

First, imbalances in consumption and production are the basis for international oil trade: close to 7 of every 10 barrels produced is exported and imported, a movement of more than 60 mmbd and the largest component of world trade (see Figure 1.2). There are net outflows of crude oil from the Middle East, North and West Africa, Latin America and Russia, and net inflows into East Asia, Europe, and the US. Layered on top of this trade in crude is an international trade in refined oil products such as diesel, gasoline, and liquefied petroleum gas (LPG), now equivalent in scale to around half the international movement of crude and increasingly characterized by “long-haul” flows to markets in Asia, Africa, and Latin America (Figure 1.3). The growing scale and geographical scope of the refined products trade reflect a number of significant economic shifts, including expansion of refinery capacity in the Middle East, increased availability of gasoline exports from the US following development of its unconventional shale resources, and rapid growth outside the OECD of consumer demand for fuels that has outstripped regional refinery capacity.

Figure 1.2 Major international trade flows, crude oil

Source: Authors, based on data from BP Statistical Review 2016

Figure 1.3 Major international trade flows, refined oil products (2015)

Source: Authors, based on data from BP Statistical Review 2016

Second, the number of consuming countries is much larger than those holding reserves – every country consumes oil to some degree while there are many without significant reserves – and consumption is less concentrated on a country basis (see Table 1.1). As a consequence, the market power of consuming countries is weak in relation to the small number of countries that control reserves and there is significant competition among importing states for access to supply. This underscores the need for countries with limited reserves but large and/or growing demand to reduce the risk associated with this relatively weak market position. The strategies available indicate the political choices at stake. Supply risk can be reduced through an increase in the intensity of domestic drilling, as pursued in the US through the rapid development of “tight oil”; by diversifying the locations from which oil is imported; by strategic investment partnerships with oil exporters to “lock in” supply outside of the market; by the use of direct military or paramilitary force to control production and supply routes; or via domestic policies that reduce demand and facilitate a transition away from oil.

Third, at the global scale, demand for oil continues to rise. Oil consumption has grown faster than population, increasing by an average of 1.44 percent per year between 2001 and 2015, despite high prices and an economic crisis in the period following 2008, compared to a slowing population growth rate of 1.18 percent. But global growth obscures a significant geographical shift in where oil is being consumed. As the world economy’s center of gravity shifts away from North America and Europe toward Asia and the Pacific, so market growth – and overall demand – has tilted decisively to the East. In China, for example, consumption grew 6.4 percent per year over that period, peaking at over 16 percent in 2004. In contrast, annual consumption in France dropped by an average of 1.5 per cent. Some of this shift in oil demand is the result of Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries outsourcing manufacturing to take advantage of lower production costs. Many of the products manufactured in these lower-wage economies are ultimately consumed back in OECD countries, although the GHG emissions associated with their production are attributed to the place of manufacture. This problem of “embedded carbon” is substantial – the carbon embedded in China’s exports is estimated to be twice as large as the UK’s carbon emissions – and an important factor in assessing responsibility for oil-related GHG emissions. An increasing proportion of Asian oil demand, however, is associated with domestic consumer spending (cars, furniture, plastic products) linked to the region’s growing middle class rather than industrial production. Consumer demand is expected to power oil consumption growth in India, China and many other countries in the region over the next couple of decades: Asia currently accounts for less than a third of the global middle class, but this is projected to grow to around two-thirds by 2030.

China’s demand for oil outstripped its domestic capacity in 1993 and since then it has been a significant importer and an increasingly assertive presence in the search for access to new reserves. The shift in the center of gravity for oil demand is associated with a shift in bargaining power among importing states – notably between the US and China – and with the development of new strategies by importing states for the acquisition and/or control of nondomestic sources of oil. Within former oil-exporting states like Indonesia, domestic growth and the development of a middle class has absorbed production and changed the direction of flow: since 2005, Indonesia has imported more than it exports. Consumption is also rising in other large producing and exporting states: Saudi internal demand doubled between 2004 and 2015. By contrast, in Europe oil demand peaked prior to the recession and is expected to continue to fall as a result of slow economic growth, climate regulation, and comparatively high taxes on fuels. Oil demand in non-OECD economies has steadily risen and passed that of the OECD in 2013. The result is that “rich countries are not setting the rules on either the demand or the supply side of the equation anymore.”7

Fourth, there is also a shift in the nature of demand toward the lighter fractions available from the refining of crude oil that are used as transportation fuels (diesel, gasoline, jet fuel) and away from heavier heating oils. Within growing markets, this is associated with an emerging middle class, growing car ownership, and air travel. Within mature markets, the shift reflects a substitution by natural gas in heating and power sectors and increasing regulation of air quality. The changing nature of demand is creating a growing “quality gap” between the direction of the market for petroleum products and the increasingly “hard-to-get” and, in the case of unconventional resources like bituminous sands, lower-quality raw materials available to the oil industry. The gap can only be met by “upgrading” the resource, implying greater inputs of energy and rising costs (often despite efficiency gains). In addition, the shift of oil into transportation and out of the power sector decreases the ease with which emissions from the burning of oil and petroleum products can be captured, ensuring a collision between “car culture” and climate change.

Fifth, the models of development that embedded oil within industrialized economies in the postwar period, later replicated in most parts of the world, took little account of the “externalities” of gathering and processing oil, turning it into durable plastics and emitting carbon dioxide and other pollutants during the combustion phase. Environmental regulation and an increasing awareness of both climate change and the wider consequences of oil development now influence the accessibility of oil reserves (e.g. environmental considerations), the price and demand for oil (e.g. via “green” taxation of fuels and carbon accounting), and the acceptability of current practices of oil extraction and use. Peak demand – rather than supply – is a reality in the OECD, while “demand destruction” is increasingly a policy objective as part of broader efforts to decarbonize economies as a response to climate change. The mismatched geographies of oil production and consumption (Figure 1.4) also raise challenging questions about responsibility for the carbon dioxide emissions associated with oil. Current approaches point to the responsibility that consumers have at the end of the carbon chain (via the regulation of emissions) rather than to the countries or companies that separate carbon from underground stocks and dispatch it into the economy. However, frameworks like the European Union (EU) Emissions Trading Scheme exclude transportation (the EU ETS has included aviation since 2012 but does not include road or diesel-powered rail transport) and so leave many of the emissions associated with oil untouched. Further, international regulation, via the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), emphasizes the historic responsibilities of countries that have been major markets for oil in the twentieth century but where demand is now in decline (the 43 industrial countries and transition economies listed in Annex 1 of the UNFCCC). The approaches currently adopted for dealing with climate change, then, are insufficient for addressing the carbon responsibilities of the oil production chain.

Figure 1.4 Oil production and consumption (2015), showing largest 25 countries (with percentages) plus rest of world

Source: Authors, based on data from BP Statistical Review 2016

Actors: states, firms, and civil society

The landscape of actors in and around oil is complex, and we examine this in more detail in chapter 2. Key actors are states, firms, and civil society organizations. Here we highlight the way these are involved with oil and point to significant emerging issues.

Oil resources are embedded – literally – in the territorial framework of states. In most jurisdictions (although not all, such as non-federal lands in many US states) oil resources are owned by national governments. Physically, legally, and culturally, oil is frequently understood as part of the “body” of the nation, so that national interests can play a decisive role in decisions about the production of oil. For states that host large oil reserves, oil can be seen as a route to modernization and development. The record on this is remarkably mixed and the state’s ownership of resources can be a means for those in power, or close to government, to capture public wealth for private gain. Many states holding large reserves have also sought to capitalize on their ownership position and become drillers, refiners, and marketers of oil via the formation of national oil companies.

The consumption of oil is also closely tied to state-level policies. Tax revenues from fuel sales, the sensitivity of economic growth to oil prices, and the geopolitics of energy security ensure that national governments have a keen interest in the accessibility and affordability of oil. High taxes on oil consumption allow some importing states to get more revenues from oil than exporting ones. National security and the ability to project “hard power” are also significant concerns for import-dependent states, as military flexibility and muscle are premised on a suite of petroleum products. National military institutions are concerned about the stalling of conventional supply and increasing competition for reserves. States also play a significant regulatory role in occupational health, safety, and the environment. National governments, then, play a larger role in oil than in many other resource sectors. An important distinction is between states that are net importers of oil and those that export. These two groups face each other on different sides of the oil market, although there is also a mutual dependency around price as higher prices for oil (which benefit exporters) can erode markets as importers reduce demand and substitute other energy sources. Tensions over price and the security of supply historically led these two groups of states to form their own “clubs” to protect their interests, in the form of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC, created in 1960) and the International Energy Agency (IEA, created in 1974).

States may own most of the world’s oil, but it is companies that search for, develop, refine, and market it. The international, vertically integrated oil firm – headquartered in the US or Europe and with extractive and marketing arms around the world – is the iconic actor, its capacity to regulate the flow from reserves to markets giving it historically a dominant position. Firms like Standard Oil and Shell defined the shape of the industry from its beginnings and into the postwar years and for this reason have become known as “the majors” or, more prosaically, “international oil companies” (IOCs). Today, “the majors” is something of an anachronism. IOCs remain among the ranks of the leading producers, but the nationalization of their crude oil assets by many reserve-holding states in the 1950s and 1960s removed their control over supply. ExxonMobil, for example, holds the most reserves of any IOC yet ranks only fourteenth worldwide, with 1 percent of global reserves. State-owned, national oil companies (NOCs), headquartered in some of the most significant oil-exporting states, decisively entered the field in the 1960s and 1970s. Building on their ownership of low-cost reserves, many of these firms have developed extensive, vertically integrated networks of distribution to markets in Europe, the Americas, and Asia. NOCs produce close to three-quarters of the oil extracted each year. Saudi Aramco, the world’s largest integrated oil company in terms of annual output, produces around 10 percent of the world’s crude and NOCs head the world rankings of oil companies by operational (as opposed to financial) criteria.

This distinction between IOCs and NOCs has historically been important for understanding competition over access to resources and markets. IOCs have been understood as “resource seeking” (in order to supply their downstream refineries and “home” markets) while NOCs have been seen as “market seeking” (looking for external markets to absorb their exports). However, this dichotomy is increasingly insufficient for grasping the global political economy of oil, for four reasons. First, the distinction typically highlighted the way NOCs operated to a national political logic rather than commercial objectives. But NOCs are an increasingly diverse group: for many state-owned firms, the level of state ownership has been reduced over time via public offering with the state retaining a controlling share, and a few have technical and commercial capabilities on a par with the IOCs. Second, IOCs and the large reserve-holding NOCs are increasingly in cooperation with one another in the development of the more challenging fields. Third – and most significantly – a number of NOCs have emerged from Asian economies that are not market seeking but resource seeking. Firms like the Korea National Oil Company, the Oil and Natural Gas Corporation (India) (ONGC), China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC), and PetroChina are state-owned firms: as important as their “national” ownership, however, is their strategy of transnationalization and their competition with the IOCs for access to resources. Fourth, with slowing rates of growth and declining margins in the historically large markets of Europe and North America, many of the IOCs are engaged in “market-seeking” activity. This includes shifting their assets to sell into the growing Asian markets while also moving more heavily into growing segments of the US and European markets such as natural gas.

Civil society, a collective term for the nongovernmental and noncorporate organizations and institutions that have come to play an increasingly significant role in public advocacy, has emerged as an important actor in the political economy of oil. Working through the medium of information and harnessing public concern to bring pressure on corporations and governments, civil society organizations have turned a spotlight on oil. Organizations like Global Witness, Oil Watch, PLATFORM, Publish What You Pay, and the Natural Resource Governance Institute draw attention to the unsavory political bargains created in and around oil and the need for greater transparency and accountability. Other groups emphasize the development challenge of oil. The strong association between oil extraction and persistent poverty (the “resource curse”) in parts of Africa, Latin America, and the former Soviet Union has sharpened the question of who benefits from oil and how oil extraction may be harnessed for sustainable forms of economic and social development. Still other civil society organizations highlight oil’s environmental deficits, from groundwater pollution and habitat loss to climate change. In short, civil society organizations have not only identified and publicized many of the negative externalities of oil production and consumption but have also contested them. Their argument, in effect, is that oil is failing in significant ways to meet broad social goals. The ways in which we access, process, and use oil, they claim, are unacceptable and something must be done.

Summary

As a result of a prodigious growth in the production and consumption of oil over the course of the twentieth century, the resource base is changing. The quality of crudes is declining: the oil added to new reserves is generally “dirtier” (in terms of energy needs and carbon contribution), more costly to extract, and located in environments that push the envelope of design and implementation. There are also uncertainties over the size of available reserves, creating concerns that the historic pattern of supply growing to match demand may no longer hold. Against this background, world demand continues to grow, driving prices and speculation about future supplies. Growing domestic demand in Asia is behind the emergence of new, state-controlled transnational firms seeking resources beyond domestic territory to supply home markets. And growing domestic demand in major oil-exporting countries suggests that their “surplus” for export will be increasingly squeezed. The 1.5 trillion barrels of oil produced to date has not only driven growth and productivity in industrial economies but has contributed to the accumulation of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, generated water and air pollution, and conspicuously failed to create a basis for social development in many oil-producing economies. This, then, is the context that defines the contemporary politics of oil.

The geopolitics of the hydrocarbon chain

The geopolitics of oil is the struggle to define who wins and who loses as oil moves from underground reserves to the point of consumption. We refer to this as “geopolitics” for two reasons. First, the “hydrocarbon chains” that ferry oil from its underground reserves into the engines of cars, cargo ships, planes, and tanks, and that transform crude into carbon dioxide, are fundamentally geographical. Oil moves across space and at key points is claimed in different ways by national governments and other interests – as a resource, as a traded good, as a source of tax revenue, as a set of development possibilities, and as environmental burdens to be allocated and addressed. Second, power and control in the oil sector are, by and large, about the control of particular spaces: the dominance of the Middle East over conventional oil reserves; the ability to exclude “foreign” firms from domestic markets; the emerging capacity of governments to regulate access to the atmosphere as a dumping ground for greenhouse gases; or the capacity to close a key pipeline or tanker route. Struggles over oil often revolve around particular sites, although their outcomes can influence the entire oil sector.

Distributional questions – who wins, who loses – are at the heart of the geopolitics of oil. Importantly, these extend beyond the traditional question of oil supply to encompass issues of resource access, value creation, price, revenue distribution, and the allocation of responsibility for pollution. In each of these cases, the things that people struggle over – the object of politics – are different: what unites them, however, is a common set of distributional concerns that center on the management and performance of the hydrocarbon commodity chain. Schematically, then, we can think of these different distributional questions as five sequential “cuts” through the hydrocarbon chain, each associated with a distinctive phase in the chain (see Figure 1.5). We expand briefly below on each of these cuts and the geopolitical issues associated with them.

Laying claim to other people’s oil: resource acquisition

Because most oil resources are owned by governments, negotiations over resource access are typically between the host state and a company seeking resources. The relationship arises because of a mutual dependence: for resource holders, the value of the resource is dependent on it being extracted and sold; and firms without access to their own resources depend on gaining access to resources owned by others. The object of politics is typically the terms of access, and the arrangements for sharing the revenues and rents that result from oil development. These tensions are seldom resolved in any final way: indeed, the agreements made between investing firms and resource-holding states have been characterized as an “obsolescing bargain” because of the way in which, when oil begins to flow, there is pressure from resource holders to renegotiate terms agreed at the outset of oil development. More generally, the historical pattern is that periods of relatively liberal resource development – in which the balance of power tilts in favor of the investing firm – are followed by periods of resource nationalism in which the resource-holding state seeks to assert its authority and wrest back some of the value that had previously been awarded to the firm. The struggle to locate oil reserves and secure exclusive control provides much of the drama in the history of oil development. From the colonial “concession” to production-sharing agreements (PSAs) and service contracts, rights of access take a variety of forms. Today, transnational state-owned firms – like PetroChina and Petrobras – are in competition with the IOCs that produce much of the world’s oil but which control a relatively small proportion of world reserves. For both IOCs and the transnationalizing NOCs, access to “other people’s oil” is an imperative. Both sets of companies call on the political resources of “home” states for support, so that a landlord–developer relationship evolves into a relationship between states. We examine the geopolitics of “capturing” resources in more detail in chapter 2.

Figure 1.5 The politics of the hydrocarbon chain

Getting a cut: value distribution

Once oil has been captured through an access agreement, the next step in the hydrocarbon chain is production. In physical terms, this is the transformation of crude into a series of products for sale to market. However, the object of politics is the way economic value is distributed along the various parts of the production chain during this conversion of crude into different petroleum products. There are many elements to this, but five – concerning companies, workers, consumers, governments, and investors – are particularly significant. First, the logic of capturing value across the production process underlies the vertically integrated character of both IOC and NOC firms, which allows the capture of profits in both the upstream and downstream reaches. Nationalizations by reserve holders in the 1950s and 1960s challenged the capture of value by IOCs and sought instead to retain it within the framework of NOCs. A further issue over the distribution of value concerns efforts by oil exporters to “upgrade” their part of the hydrocarbon chain by moving into downstream processing. Second, the creation of value in the hydrocarbon commodity chain rests on the labor of millions of people. A complex and diverse range of livelihoods manipulate oil’s flows – from oil-field workers and gas pump attendants, to white-collar energy traders and illegal fuel runners. Oil work can be influential, from the capacity of refinery workers to strike, to the lobbying and philanthropic power of oil magnates. Oil work is also gendered, raced, and made synonymous with national identity in certain contexts. These and other factors influence the differential ability of workers to secure value from their labor along the hydrocarbon commodity chain, whether in the form of livelihoods that are economically secure, or conditions and rhythms of work compatible with other life activities (e.g. family, leisure time). Third, the distribution of value to end consumers versus producers revolves around the crude oil price. If producers can secure control over a significant proportion of supply, they are able to exert an upward effect on prices. Rises in price erode value for consumers but, as long as production costs do not also rise, they increase value for producers. The erosion of value can be particularly acute for poor importing states, and high oil prices have significant implications for their development. OPEC’s actions in the 1970s demonstrated the ability of producers to club together to control supply for short periods of time, although this was undermined by diversification of supply and competition within OPEC for market share. Fourth, consuming governments also siphon value from the hydrocarbon chain via the taxation of fuels. In Europe, this “tax wedge” is large and has become a target for political protests from road users. Fifth, the ownership of “paper oil” – the trading of oil futures without the intention of taking physical delivery – allows financial managers to capture value from, and create, shifts in price. Against a background of anticipated supply shortages and growing Asian demand, the role of speculation in driving price is now a major concern for oil importers and consumers. We examine the question of how value is distributed in chapter 3, with a particular focus on price, and chapter 4 which centers on labor.

No surprises: securing flow

A third “cut” across the hydrocarbon chain highlights the question of securing the flow of oil between net exporters of oil, countries that produce more than they consume, and oil importers that do not produce any or enough oil for domestic demand. This is a relationship based on the physical movement of oil via trade and a reciprocal flow of revenue, and the mutual needs of importing and exporting states for reliable trading partners. The object of this relationship is the security of supply. The vulnerabilities and strategic opportunities created by flows of oil and money are at the core of international geopolitics, and structure the domestic politics of large exporting and importing states alike. Both the US and China, for example, are major producers of oil but these countries consume over twice the amount available from domestic supply. The consistent shortfall in domestic production relative to domestic demand in these countries exerts a significant influence on their foreign policy: whether via oil diplomacy, development-for-oil deals, or the projection of military force, the need of large oil-importing states to secure sufficient extraterritorial supplies of oil is a key feature of the global economy. On the other side of the coin, Russia is also one of the world’s major oil consumers – it ranks fifth in the world in terms of its annual consumption of oil – but it produces around three times as much oil as it consumes and so is a leading exporter. Large exporters are also concerned about energy security, which for them means a concern about the loss of markets to new entrants, via the corrosive effect of high prices on demand or regulation of carbon. We examine this dynamic of securing supplies and markets in chapter 5.

Avoiding the curse: modernization and development

A fourth cut illuminates the question of how oil contributes to economic and social development. It centers on the relationship between the national and regional governments of oil-producing and -exporting states and their peoples, and the extractive firms that pump, refine, and export crude. Oil often fuels dreams of development, yet the reality of modernization through oil frequently falls short. Tensions revolve around the management, or squandering, of oil revenues, the creation of oil dependency, and the challenges of the so-called “resource curse” – that countries with abundant natural resources tend to have worse development outcomes than those with limited endowments. At a national scale, it is useful to distinguish between so-called high absorbing states that do better at incorporating oil revenues into their economies; and low absorbing states where governmental authorities lack the capacity to handle the large and volatile revenue streams associated with oil exports.

A critical question is how revenues are distributed geographically and across different social classes and ethnic groups. The issue here is the extent to which communities that host oil wealth are compensated for its extraction and the social, economic, and environmental dislocations this can cause. Tensions frequently arise between a central government (the owner of oil underground) and regional governments that administer lands and other resources in the area of oil development.

Accounting for nature: pollution

The fifth and final cut relates to the politics of emissions from the hydrocarbon chain. These occur all along the chain in the form, for example, of local groundwater contamination, ocean pollution, habitat loss, urban smog, and global climate change. Critical questions are the distribution of these pollutants – where they go and whom they affect – and the allocation of responsibility for addressing them. A growing alliance of civil society organizations and some governments are calling oil companies to account by demanding they address historic responsibilities for pollution (e.g. Chevron in Ecuador). Others seek moratoria or bans on drilling in sensitive environmental settings such as the Arctic. Increasingly, however, it is around the role of the hydrocarbon chain as a carbon conveyor – transforming fossil stocks of carbon into atmospheric carbon dioxide – that the politics of pollution revolves. The question of responsibility here is particularly significant. Conventional approaches highlight carbon emissions rather than the throughput of fossil fuels in the economy. An alternative approach, however, is one that seeks ways to prevent oil from being extracted in the first place by generating revenue streams from the protection of habitat or forgone carbon emissions. We explore the politics of development and environment in chapter 6.

Conclusion

In the twentieth century, oil politics centered on the management of abundance, state power, and market growth. The remarkable energy surplus made available through oil transformed the experience of space and time for many of the world’s population during that period; for many others, it fostered dreams of economic and social transformation. Today, the legacies of this “Age of Plenty” include volatile prices, dwindling conventional oil reserves, climate change, and enduring poverty in many oil-rich countries. Our goals in this chapter have been to identify those characteristics of the contemporary oil sector that differentiate it from the “Age of Plenty”; establish how these are linked to previous waves and historic practices of oil-fueled development; and indicate how these conditions add up to a new geopolitics of oil. Deteriorating resource quality and growing uncertainties over reserves, the rise of consumerism in Asia, the internationalization of state oil firms, and the tentative emergence of nonfossil alternatives to oil are signs of an industry being reordered by a range of powerful forces. The following chapters are organized around five critical tensions that are currently shaping the sector: the geopolitics of resource access; the volatility of oil prices; security of supply; the possibilities of development through oil; and the environmental consequences of oil production and consumption. The future of oil will be determined through the ways these conflicts are addressed. In the pages that follow, we show how this new geopolitics is bringing into question commonplace assumptions about the governance of oil, while also raising fundamental questions about who now governs oil and for whom.