Creationism and Intelligent Design

Eugenie C. Scott

OUTLINE

1. What kind of creationist?

2. The creation-evolution continuum

3. Intelligent design

4. What does the future hold?

Many are unaware that there are several kinds of creationisms, even within the tradition of Christianity. In that tradition, the various creationisms are a function of how the Bible is interpreted, and the differences reflect how much of modern science is accepted. Intelligent design is a more recent form of creationism, but in its particulars it reflects themes similar to other forms of Christian creationism. New forms of creationism may develop in the future, but it is likely that they will reflect the same ideas as their ancestors.

1. WHAT KIND OF CREATIONIST?

There has been a long-standing tension between some religious groups and evolutionary biology, and that tension plays out in schools throughout the United States. At the National Center for Science Education, we monitor the creationism and evolution controversy, and we help parents, teachers, and others cope with challenges to evolution education. All the challenges emanate from people who call themselves—or can be called—“creationists.” Often, a student will tell a teacher, “I don’t believe in evolution, I’m a creationist.” We recommend asking in reply, “What kind of creationist?”

It is a teachable moment: the student has probably never considered that there might be more than one type of creationism, and the teacher has the opportunity not only to expand the student’s horizons but also, with luck, to reduce barriers to learning evolution. And yes, it is also an opportunity to help the student understand that scientists don’t “believe” in evolution, they accept common ancestry as the best explanation for the patterned differences and similarities among living things. That is, the word belief evokes positions held with or without evidence; hence, belief is at best an ambiguous word to use in the context of science. Scientists don’t “believe” in evolution any more—or less—than they “believe” in thermodynamics.

“Belief” in evolution, as it is too frequently termed, occurs at a lower frequency in the United States than in almost any other developed country. Only about 47 percent of Americans accept that all living things have common ancestors, far less than in Western Europe and Japan, where the percentages are above 70 percent and even 80 percent, respectively. Survey research shows a major disconnect between the US public’s acceptance of evolution and that of scientists. In one survey of members of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, the world’s largest association of scientists, 97 percent accepted the statement that “humans and other living things have evolved over time.” High school teachers are more likely than the general public to accept evolution as a scientific concept, but only about 30 percent report that they teach it extensively. Fully 60 percent admit that they either omit evolution or give it short shrift. The reasons include the teachers’ apprehension that evolution is a controversial issue, personal religious beliefs, and the feeling that their education did not prepare them to teach the subject well.

Teachers in the United States can expect that their students who describe themselves as creationists will usually base their creationism on some form of Christianity, the religion of most Americans, and almost always on Christianity, Islam, or Judaism. But there are exceptions: some teachers in communities where Native Americans are numerous have also reported pushback on the teaching of evolution. Other forms of creationism based on Hindu and various New Age religious beliefs also occasionally surface in the classroom.

We should therefore speak of creationisms in the plural. This point reveals as problematic the long-standing plea of antievolutionists that teachers should “teach both” evolution and creationism. How should a teacher choose which creationist version to contrast with evolution? Even supposing that there was some reason to privilege Christianity over other religions, there are several distinct versions of Christian creationism, corresponding to the different ways in which scripture is identified and interpreted by various denominations. Mormons revere the Book of Mormon, and Seventh-Day Adventists regard the writings of Ellen Gould White as inspired; which, if either, should a teacher present? Even if only the Bible is considered, whose Bible?—the King James version, the New Jerusalem version (favored by Catholics), the New International Version (favored by Evangelicals), the New Revised Standard Version (favored by mainline Protestants), or one of the scores of texts available? And given a particular version of the Bible, who is to decide which verses are relevant and how they are to be understood? In fact, these complications only scratch the surface, and the following discussion of the varieties of Christian creationism is necessarily abbreviated.

2. THE CREATION-EVOLUTION CONTINUUM

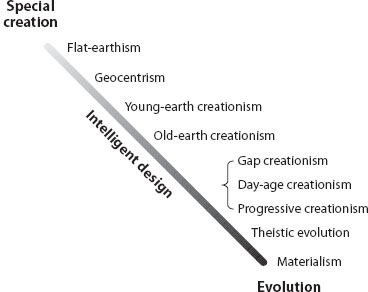

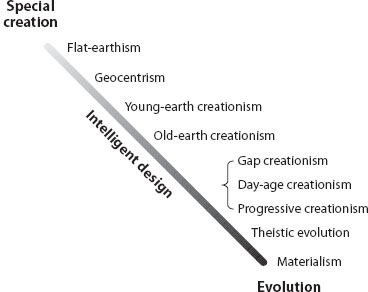

Creationism, as usually encountered in the United States, is based on a “plain” reading of the Bible. Taking the creation narrative in Genesis 1 as authoritative, creationists hold that God specially created the universe, the planet earth, and the living things on it. There are many ways to read the Bible, and the varieties of Christian creationism can be viewed on a continuum reflecting how literally they interpret the words of Genesis and how far their interpretation lies from mainstream science (figure 1).

Figure 1. The creation/evolution continuum.

Flat-Earthism

It is almost comical to believe that flat-earthers can exist in the twenty-first century. Nonetheless, until his death in 2001, Charles K. Johnson was president of the International Flat Earth Research Society, a small organization whose interpretation of the Bible is so extreme that passages referring to the “circle of the Earth” (circles are two-dimensional, while spheres are three-dimensional) and the “pillars of heaven” (supports for a metal dome or “firmament” arching over a horizontal planet) are interpreted as stating that the earth is flat. Few Christians take the Bible so literally, but geocentrists are only slightly more liberal in their exegesis.

Geocentrism

Geocentrists believe that the Bible presents earth as the center of the solar system. Passages cited include Joshua 10:12–13, in which God complies with Joshua’s plea to stop the sun over the Valley of Ajalon, which requires a stationary earth. Both flat-earthers and geocentrists contend that one cannot pick and choose passages of the Bible to “interpret,” so the entire Bible must be accepted as received. If Genesis is not true, they argue, how can we be sure of any of the rest of the Bible, including the New Testament and Revelations, which promise salvation? As Gerardus Bouw, a modern geocentrist author, asked, “If we cannot take God’s word as to the rising of the Sun, how can we believe him as to the rising of the Son?”

Geocentrism fought it out with heliocentrism, the idea of a sun-centered solar system, during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Heliocentrism eventually would have won because the science was right, but its acceptance was helped by a shift in church doctrine at that time away from the strict biblical literalism of the Middle Ages and early Renaissance periods. As a result, even most creationists accept heliocentrism.

Young-Earth Creationism

Young-earth creationists (YECs) agree on the importance of a plain reading of the Bible, although they do not think that requires belief in a flat earth or geocentrism. YECs are currently the most numerous creationists in the United States. YECs understand Genesis as stating that creation took place over six 24-hour days, during which God created the universe in essentially its present form. Following Archbishop James Ussher, a seventeeth-century Irish cleric, YECs hold that earth was formed only thousands, not billions, of years ago. Animals and plants were created as separate and independent “kinds” and do not share common ancestry. Humans in particular are independent creations, made in God’s image.

Most YECs also support the movement known as “creation science,” which in its modern form began to be promoted in the 1960s by Henry M. Morris, founder of the Institute for Creation Research (ICR) and its leader until his death in 2006. Morris was highly respected among conservative Christians, and his influence can hardly be overestimated. The movement Morris originated contends that the data and theory of science support the claims of the Bible in all its details. The special creation of all living things by God and the existence of a worldwide Noachian flood (a literal interpretation of Genesis 6–9) are held to be supported not only by faith but also by science.

The science of creation science, however, is decidedly lacking in quality. The logic of creation science is clearly stated by Morris and his followers: evidence against evolution is evidence for creationism. This approach solves their problem of finding scientific evidence for the sudden appearance of living things in essentially their present form, which special creationism requires. But it also means focusing only on anomalies purporting to disprove evolution and ignoring the massive evidence supporting it. There is ample literature wherein scientists have examined the claims of creation science and found them both factually wrong and theoretically empty. But proponents loudly, if ineffectually, defend their claims that creationism can be made scientific.

Morris firmly believed that a universe measured in thousands of years is foundational to a proper interpretation of the Creation story in Genesis. The only acceptable understanding of creation, then, is young-earth creationism. It is true, of course, that if the earth were young, there would not have been time for much astronomical, geological, or biological evolution. For this reason, YEC institutions including the ICR and Answers in Genesis adhere to Morris’s original vision.

YECs insist that just as a young earth is foundational to creationism, so also is the Creation story foundational to Christianity. Christianity’s central pillar is the sacrifice of Jesus on the cross to redeem humankind’s sins. YECs believe that if Adam and Eve had not been specially created by God, sinned, and punished by being driven from the Garden of Eden, as described in Genesis, then there would not have been a need for a Savior to redeem the sin of Adam. If there was no need for Christ’s life, death, and resurrection, as described in the New Testament, then there is no reason to believe the promise of eternal life in the Book of Revelation. The credibility of the entire Bible is thus contingent on the credibility of the special creation of earth and of Adam and Eve. Evolution is therefore unacceptable to YECs.

In Morris’s version of young-earth creationism, all sedimentary geological features are the result of Noah’s flood, and scientific evidence is sought to support this conclusion. The geological column, it is claimed, only appears to present a succession of fossils showing the gradual emergence of present-day forms from earlier forms. Accordingly, the geological succession of fossils resulted from the “hydrodynamic sorting” of the remains of organisms that died in Noah’s flood. It is claimed that spherical and smooth organisms such as clams would more likely be found at the bottom of the column because such shapes fall through water more readily than irregular shapes. Jointed organisms with irregular shapes, such as dinosaurs, would be found higher up. And the smarter, more mobile organisms such as mammals would likely have sought higher ground to avoid the floodwaters, explaining their occurrence higher in the geological column. These views are supported by carefully chosen examples—and by ignoring the copious data that refute them.

Old-Earth Creationism

Old-earth creationists (OECs) have perhaps the most variable positions on the continuum. OECs are special creationists, believing that God specially created living things as identifiable “kinds,” and thus they reject biological evolution. But they accept the evidence from physical science that our planet and the universe are ancient. Many OECs even accept an earth that is billions of years old. A common view among OECs is to identify the Big Bang as the creative event of Genesis 1. OECs thus consider themselves true to the Bible while accepting the evidence of planetary and cosmic deep time. But among OECs, adherents “interpret” the holy text in various ways to make it compatible with an old earth.

Gap creationism requires the least tinkering with Genesis. Sometimes called “ruin and restoration” theology, gap creationism sees the possibility of two creations in Genesis, with a long period of time between them. The first creation was of a world before Adam and is referenced in the familiar words of Genesis 1:1—“In the beginning, God created the Heaven and the Earth.” God then destroyed that creation, a great deal of time passed (“the Earth became without form and void, and darkness was upon the face of the deep”), and then, as stated in Genesis 1:2–31, He created the present world and its inhabitants in six 24-hour days. Gap creationists thus interpret the Bible very literally, though with room for an old earth. It is not surprising that enthusiasm for gap creationism grew in parallel with the rise of modern geological sciences in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Day-age creationists, by contrast, believe that the six days of creation were not 24-hour days but instead long periods of indeterminate duration—perhaps hundreds of thousands or even millions of years. They retain reference to a literal Genesis six days but they, too, allow for an old earth. They cite biblical passages such as Psalm 90:4 (“For a thousand years are in your sight like a day”) to suggest that the days of creation need not be 24 hours long. Yet another group of OECs downplays the idea of six days, believing instead in an interventionist God who sequentially—and specially—created living things over immense amounts of time. These “progressive creationists” thus accept the geological column as reflecting an accurate history of life on earth but do not believe that the sequences of organisms reflect evolutionary continuity.

All the positions on the continuum discussed thus far are forms of special creationism. But the continuum can be extended to include additional positions on the relationship between the Bible and science. The positions discussed next all accept the mainstream scientific findings of astronomy, geology, and biology—hence, none of them are creationist positions—but they differ from one another on theological or philosophical grounds.

Theistic Evolution

The abandonment of special creationism is clear in the next position on the continuum. Theistic evolution (TE) can be described as the belief that evolution has occurred but that God uses evolution to bring about the universe, earth, and living things. Unbeknown to most Americans, TE is mainstream Christian theology, routinely taught in Catholic and Protestant parochial schools. It is considered uncontroversial in many Protestant denominations such as Episcopalians, Presbyterians, United Church of Christ, and in the less conservative branches of Lutherans and Methodists. Thus, when teachers hear students say “I don’t believe in evolution, I’m a Catholic,” it should be evident that the student is unclear on both science and theology. Embedded in the hallway of a new science building at Catholic Notre Dame University is a large mosaic, 5 ft in diameter, that quotes an aphorism by a famous twentieth-century geneticist, Theodosius Dobzhansky: “Nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution.”

In TE, God did not have to create organisms as we see them today: organisms can descend with modification from earlier forms. Believers in TE scorn biblical literalism, being critical of the literalists not only for views incompatible with modern science but also for theological views they consider outmoded and inconsistent. The TE view is that Christian theology must reflect what we know of the world from science if it is to be coherent. Unlike YEC and OEC, the TE view accepts standard scientific interpretations of evidence from geology, physics, chemistry, and biology that indicate that the universe has a long history and that organisms have evolved. Like all theists, adherents to TE believe that the universe was created for a purpose, which science cannot address, although science can address and explain the processes involved in the creation of that universe.

TE believers range along a continuum of their own, varying in how much and in what ways God intervenes over time. Divine intervention is usually conceived as miraculous: with miracles, God violates His created laws, such as by raising Jesus from the dead. However, it is important in TE also for there to be minimal intervention. This “economy of miracles” reflects theological issues not germane to this discussion, such as free will, and the consequences of God “breaking” his own laws. So varieties of TE differ in the degree to which God was “hands-off” in the creation—from one in which God set forth the laws of the universe and allows it to evolve without intervention, to another interpretation in which God also created the first replicating organism (after which evolution proceeded naturally), to yet another in which God intervened also to bring about the evolution of humankind.

The amount of divine action in the creation of the universe is not the only criterion shaping TE views. Like other Christians, believers in TE are also concerned with the degree to which the Deity is personal: an entity who is involved in a meaningful way with the self. One extreme is again a God who created the laws of the universe and is thereafter uninvolved. At the other extreme is the interventionist God to whom one might pray and hope to receive an answer.

The continuum thus far has expressed a greater or lesser reliance on biblical literalism. It has also reflected an inverse acceptance of modern science, with the flat-earthers and geocentrists rejecting some of the most basic facts of modern science, YECs rejecting less familiar but core principles of physics and geology (such as radioisotopic dating) and biology, OECs more or less accepting the physical sciences but rejecting modern biology, and TEs accepting the conclusions of all modern science. All the positions discussed so far have been theistic ones: God exists and is in some way involved in creating the universe in which we live. Next on the continuum are materialists, who reject the concept of a God or higher power.

Materialism

Because this chapter deals with creationism, the nuances and variations of materialism will not be discussed in detail. Briefly, materialists believe that matter and energy not only are sufficient to explain the physical universe, as with science, but also are sufficient in a metaphysical sense: there are no gods or supernatural forces or powers. Among materialists there are agnostics, who agree with Thomas Henry Huxley (who coined the term agnostic), that one can never know for certain whether there is a God. Agnostics suspend belief. Atheists deny belief in God or gods, and there is a debate among them whether atheism is a philosophical system or merely the denial of the supernatural. Humanism is a nontheistic philosophical system with deep historical roots.

3. INTELLIGENT DESIGN

What about the intelligent design (ID) movement? On the diagram of the continuum (figure 1), it is shown straddling OEC and YEC, because ID is, at heart, special creationism, but carefully formulated not to take a stance on the issues that separate OEC and YEC. (In the words of one of the early collections of ID writings, ID espouses “mere creation.”) While ID is sometimes erroneously conflated with TE, in practice the ID movement has consistently been antievolutionary in its focus. Also, leaders of the ID community have strongly rejected TE, and the rejection is mutual. Nonetheless, ID has also been criticized by proponents of YEC and, despite some initial enthusiasm, by some leaders in the OEC community.

The reasons for this apparent contradiction lie in the history and content of ID and the strategy its leaders have used to promote their view to the public. The history of ID shows it emerged from a group of OECs (and some YECs) in the mid-1980s. These conservative Christians were dissatisfied with the lack of progress of the YECs in convincing the public to reject evolution or, at least, to accompany its teaching with some form of creationism (such as creation science). At the time, laws promoting equal time for creation science were being tested in the courts, and after a thorough defeat in an Arkansas federal district court, creationists realized that creation science was too obviously tied to Christian religion to survive the Establishment Clause of the United States Constitution. That clause requires public institutions to be religiously neutral. Teaching creation science was judged to be the promotion of religion and thus unconstitutional.

ID emerged as a stripped-down form of creationism out of a series of private meetings (attended by both YECs and OECs) and from the production of a supplemental high school textbook, Of Pandas and People, intended to “balance” standard evolution-based textbooks. It ignored creation science favorites, such as the age of the earth and Noah’s flood, in favor of the core creationist principle of special creation, although the term creationism was (and is) carefully avoided. The ID movement reflected the “argument from design” of William Paley’s 1802 book, Natural Theology, which compared highly complex biological structures to human-made artifacts. Paley contended that just as a pocket watch could not have assembled itself but required a watchmaker, so, too, a complex biological structure such as the human eye also required a designer and artificer—God. Modern ID examples tend to focus on the complexity of molecular structures. The flagellum of a bacterium is a favorite example of a biological “engine” that is “irreducibly complex” (supposedly too complex to have been produced through natural selection) and thus, it is argued, the product of design by an intelligent agent. Such irreducibly complex structures are called forth in abundance: DNA, the first cell, the body plans of invertebrate phyla of the Cambrian explosion, and so on. Whenever such irreducibly complex structures are discovered, an intelligent designer is invoked, because great complexity is assumed to be unattainable through natural causes.

Who is the intelligent designer responsible for such structures? Proponents of ID are often coy, suggesting that it could be extraterrestrial aliens or time-traveling cell biologists from the far future. However, the more candid among them will acknowledge that they believe the designer to be God, even while agreeing that that is a conclusion unwarranted by science. But when an intelligent agent is invoked at every appearance of an irreducibly complex structure, what is being proposed is actually a form of progressive special creationism. At the grassroots level, ID is understood to be about creationism, with God as the designing agent—even if the leadership of the movement attempts to obscure these identifications to avoid running afoul of the Establishment Clause.

In 1987 the Supreme Court declared in Edwards v. Aguillard that teaching creation science in the public schools was unconstitutional. Therefore, when a school board in Dover, Pennsylvania, required teachers to teach ID, lawyers for the plaintiffs in the subsequent 2005 federal district court trial Kitzmiller v. Dover sought to demonstrate historical links between creation science and ID. They were successful: such links were crucial in the judge’s decision to declare ID a religious rather than a scientific view and that the teaching of ID therefore violated the Establishment Clause.

With ID’s roots firmly in creation science, why have the two most prominent YEC organizations, the Institute for Creation Research and Answers in Genesis, attacked ID? Part of the ire of the YECs toward ID arises because of a strategy of ID leaders to omit biblical themes such as the flood of Noah, the special creation of Adam and Eve, and a young age of the earth. OECs tend to outnumber YECs in the leadership of ID and, in fact, ID was largely unknown other than to creationism watchers until 1991, when University of California, Berkeley, law professor Phillip Johnson’s book Darwin on Trial was published. It is not unusual for antievolution tracts to emerge from creationist institutions or Bible colleges, but such tomes rarely emanate from faculty at major secular universities.

Johnson arguably put ID on the map, as far as the public was concerned, and Johnson’s leadership in shaping the legal and philosophical approach of ID was substantial during the 1990s and early 2000s, until ill health required him to take a lower profile. Among other things, Johnson contended that all Christian creationists should unite to attack evolution, setting aside their young-earth versus old-earth squabbles and other differences until they had convinced the public of the scientific and religious shortcomings of evolution. Once evolution was defeated, all the creationists could have a polite discussion over their differences. This strategy may have been appealing to individual creationists, but established creationist organizations were resistant to stepping back from their cherished positions. Eventually they declared that ID—correct in its bashing of evolution—nonetheless was doomed to failure because it would not bring the public to Christianity unless it put the Bible at the center of its mission. And that, of course, was at the heart of the matter. Merely persuading the public that evolution was unsupported by science and inherently atheistic was inadequate: it was necessary to replace evolution with special creation.

4. WHAT DOES THE FUTURE HOLD?

Disagreements among leaders of the creationist movements are only part of the story. What is perhaps more significant is how these movements are viewed by the public. The differences between YECs and OECs are stark, and a choice must be made between an earth that is billions of years old or only a few thousand years old. ID, meanwhile, is commonly considered to be an adjunct to either the YEC or the OEC perspective. Rather than viewing ID as the sophisticated scientific argument dreamed of by its proponents, most members of the public who are familiar with it see it as a generalized form of creationism—which, in fact, it is.

Since the Kitzmiller v. Dover trial, the ID star has burned a bit more dimly. Leaders of the movement, affiliated with the Seattle-based Center for Science and Culture at the Discovery Institute, are now encouraging legislation and regulations that would encourage the teaching of “evidence against evolution.” Sometimes, evolution is bundled with other “controversial issues” such as global warming and human cloning for special treatment in the curriculum. A common tactic calls for teachers to be given “academic freedom” to bring in “alternative views” to those expressed in the textbook or state standards. In the case of evolution, of course, “alternative views” is a euphemism for creationism. It appears to be a popular strategy for promoting creationism: more than 40 “academic freedom”–style bills were proposed in various state legislatures in the decade 2003–2013, although opponents managed to defeat almost all of them in committee. When such bills reach the floors of their respective chambers, however, they are often difficult for elected officials to publicly oppose. Two bills have passed: one in Louisiana in 2008 and one in Tennessee in 2012.

In contrast, YEC is thriving, although explicit attempts to promote the teaching of creationism in the public schools are rare. Particularly prominent is the Answers in Genesis ministry, which since its founding in 1994 has been remarkably successful at capturing the market for creationism. This success is apparently due in part to its adopting a style heavier on evangelism and lighter on science than the Institute for Creation Research and in part to its use of the latest technology, including a well-crafted website. Answers in Genesis also opened a lavish “Creation Museum” in northern Kentucky in 2007, which may be joined in the future by a Noah’s Ark theme park. The Institute for Creation Research has moved to an expanded new campus in Dallas, Texas, and is expecting to rebuild its own museum in that city. Several smaller creationism museums are in the planning stages or have already opened.

All in all, it appears that the creationism movement in the United States is prospering. And given its fragmented history, it is safe to say that even if some constituents fall out of favor, new varieties will emerge somewhere on the continuum.

FURTHER READING

Berkman, M., and E. Plutzer. 2010. Evolution, Creationism, and the Battle to Control America’s Classrooms. New York: Cambridge University Press. Invaluable for its extensive, thoughtful, and fruitful use of survey data, especially its rigorous national survey of high school biology teachers.

Forrest, B., and P. R. Gross. 2007. Creationism’s Trojan Horse: The Wedge of Intelligent Design. Rev. ed. New York: Oxford University Press. The definitive exposé of intelligent design as a strategy of rebranding creationism, updated with a chapter on events after the Kitzmiller trial.

Larson, E. 2003. Trial and Error. 3rd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press. The authoritative history of the legal struggles over the teaching of evolution in the United States, although it stops short of the Kitzmiller trial.

McCalla, A. 2006. The Creationist Debate: The Encounter between the Bible and the Historical Mind. New York: Continuum. A synoptic history of the creationism/evolution controversy, focusing on the development of the historical sciences and how the ways of interpreting the Bible developed in response.

Numbers, R. L. 2006. The Creationists: From Scientific Creationism to Intelligent Design. Exp. ed. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. A monumental work on the history of the creationist movement, newly updated with a chapter on intelligent design.

Pennock, R. T. 1999. Tower of Babel: The Evidence against the New Creationism. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. The first, and still a valuable, examination of the intelligent design movement, by a philosopher who testified at the Kitzmiller trial.

Ruse, M. 2005. The Evolution-Creation Struggle. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. The distinguished philosopher and historian of science attempts to understand the roots of the creationism/evolution controversy.

Scott, E. C. 2009. Evolution vs. Creationism: An Introduction. 2nd ed. Berkeley: University of California Press. A comprehensive history, commentary, and sourcebook on the creationism/evolution controversy.