IF BOB DYLAN had always been capable of cruelty, he now surrounded himself with a coterie of cronies who actively encouraged his mean streak. They included Eric Andersen, Jack Elliott, David Cohen (aka David Blue), and others. But foremost among them was the charismatic Bobby Neuwirth, a Boston-based painter who sang and played banjo and hung around Club 47.

“Bobby didn’t play a lot, but he was painting, and he’d been to the Boston Museum School,” says John Byrne Cooke, who’d roomed with Neuwirth in Cambridge. “You could say there was a certain similarity of style between him and Dylan. It was a synergistic relationship. Dylan was not exactly a chameleon, but there were a number of people that he drew from.” Dylan himself would compare Neuwirth to Neal Cassady, the inspiration for Dean Moriarty in Kerouac’s On the Road, writing in Chronicles that “you had to brace yourself when you talked to him” and that he “ripped and slashed and could make anybody uneasy.”

Neuwirth had first met Dylan in 1961 but was now firmly at the heart of Dylan’s inner circle, to the point that some onlookers thought he had the singer under a spell. “I could never figure out whether it was Dylan who’d copped Neuwirth’s style or vice versa,” wrote Al Aronowitz, one of their many victims. But Al Kooper, who got to know the duo the following year, was convinced that “Neuwirth was actually the personality: he was the creator of the image and Dylan just jumped on it.”

If the Dylan-and-Neuwirth combo was at its most vicious holding court in the Village at the Kettle of Fish—where rivals like Phil Ochs were routinely humiliated—it was no less lethal up in Woodstock. “What they used to do, they called a ‘truth attack,’” says Billy Faier. “Upstairs at the Espresso, I’m talking to the Paturels about running for office in Woodstock. Dylan starts a truth attack: Do I really think I could do any good, even if I won, which I undoubtedly wouldn’t? All this really negative stuff. He would interrupt me whenever he wanted, and then Neuwirth would interrupt in specific places where he was supposed to. You could see the pattern.”

Faier also observed the cruelty later meted out to Victor Maymudes. “Victor was no longer Dylan’s sidekick, but we’re in Woodstock, and he says, ‘Hey, I’m going up to visit Albert, you wanna come?’” Faier recalls. “So we go to Albert’s, and he’s sitting at a big table outside with everybody, and Sally is waiting on them, and we’re both just sitting there with our thumbs up our asses. You could see that Victor was miserable, but he couldn’t tear himself away. So I said, ‘Come on, these people are not your friends.’ And we left.” Maymudes later described Grossman as “an asshole who bent over for quarters when thousands were flying by.”

Others were more forgiving of the “mind guard” that Neuwirth provided for Dylan. “Neuwirth was kind of a guide dog, and Bob needed that,” says Donn Pennebaker. “Bob felt very vulnerable to certain attitudes and tried to avoid them whenever he could. And Neuwirth helped to keep him out of this morass. Bob expressed it sometimes as throwing pearls to swine: the idea of trying to explain what he was doing, to people who didn’t understand. Neuwirth protected him from that role.”

Among those who now felt the sting of Dylan’s and Neuwirth’s sadism was Joan Baez, the treatment of whom went far beyond affectionate teasing. Deciding that she was the epitome of all that was uncool—the embodiment of unctuous folk goodness, in fact—they undermined and belittled her at every turn. Like a neglected puppy following its abusive master, she strung along on Dylan’s English tour in the spring of 1965, Pennebaker filming her humiliation for all to see. By her own admission she couldn’t tear herself away.

Just as he had two-timed Suze Rotolo with Joan Baez, so now Dylan two-timed Baez with Sara Lownds. “Don’t worry,” Mimi Fariña overheard him say on the phone after her sister had gone. “She just left.” Lownds was a kind of Jewish Madonna: there was something mysterious and melancholy about her that made her an irresistible muse. “It was almost like she was surrounded by mist,” says Norma Cross. “She was very involved in mystical or spiritual things. We were all throwing the I Ching in those days, but Sara went beyond that.” A decade later, on Desire’s “Sara,” Dylan called her his “radiant jewel, mystical wife,” a “glamorous nymph with an arrow and bow.” At least a part of the attraction was that she wasn’t overawed by him.

“She was just gorgeous-looking,” says Donn Pennebaker. “If we accept the Schopenhauer idea that you recognize in somebody the children you want to have, maybe something like that took place for Bob.” In New York he moved into the Chelsea Hotel to be near Lownds and her daughter. In Woodstock, meanwhile, he installed them in Vera Yarrow’s cabin. “We made a picture in the backyard,” says Daniel Kramer of a March 1965 photo session there. “We emptied out the shed, and Sara posed for me. We called it ‘The Shack.’” Sara had already appeared in photographs taken by Douglas Gilbert at the Espresso, where—with short, boyish hair and wearing a Breton shirt—she was the object of besotted glances from not just Dylan but John Sebastian, Victor Maymudes, and Mason Hoffenberg. “He obviously fell for her,” Sally Grossman told David Hajdu, adding that Dylan wanted the relationship to be kept quiet. “That was one of our jobs, to help give him that privacy.” Over a decade later, Lownds and Baez would reminisce about the months when Dylan was seeing them both; they even appeared together in his 1978 film Renaldo & Clara. Off-camera, Baez alludes to a “lovely blue nightgown” that Dylan had once given her. “Oh, that’s where it went,” Sara says with a laugh.

As hard as it was for Baez to view Dylan dispassionately, she was genuinely concerned as she watched him being enveloped by what she described as “a huge transparent bubble of ego.” Irwin Silber said much the same thing in his famous “Open Letter to Bob Dylan,” published in the November 1964 edition of Sing Out!: “You travel with an entourage now—with good buddies who are going to laugh when you need laughing and drink wine with you and ensure your privacy—and never challenge you to face everyone else’s reality again.”

Even before her humiliation in England, Baez was alarmed by the changes in Dylan—changes that had at least something to do with a trip he made into New York in late August 1964. It was Al Aronowitz who’d suggested Maymudes drive Dylan down from Bearsville to meet the Beatles. Aronowitz had reported on the group’s tumultuous arrival in America that February, and now he had a green light from John Lennon to extend an invitation to one of their only real peers. “I want to meet him,” Lennon told Aronowitz, “but on my own terms.” Aronowitz recalled the meeting at the Delmonico Hotel as initially “very awkward, very demure. . . . Nobody wanted to step on anybody’s ego.” The encounter has gone down in pop history as the day Dylan turned the Beatles onto marijuana, but equally important was the effect the meeting had on Dylan, who—at the time he saw their show at the Paramount Theatre on September 20—was becoming a bona fide pop star. And when the Fab Four’s fellow British invaders, the Animals, hit number 1 that month with their version of “The House of the Rising Sun”—a song he had himself sung—Dylan was knocked out by its bluesy electric arrangement.

“When I first met him, Bob was a folk-music protest singer, and he pooh-poohed rock music,” Al Aronowitz told me. “My position was that today’s hits are tomorrow’s folk music. Later he wrote me a letter from England telling me that I was right. My wife even drove him to Rondout Music in Kingston to buy an electric guitar.” Dylan was hardly a stranger to rock and roll. He’d played in amplified bands back in Minnesota. His first Columbia single used electric backing. But he knew full well how the Sing Out! crowd would respond to any “Beatle-ization” of his music. Over Christmas and New Year’s 1964–1965, with band arrangements in his head, he spent two weeks in the White Room in wintry Woodstock finishing up the songs for his fifth album. “My songs’re written with the kettledrum in mind,” he stated in the liner notes to Bringing It All Back Home, adding that his poems were “written in a rhythm of unpoetic distortion/divided by pierced ears.”

When that album was released in late March 1965, it was split between electric and acoustic sides. Producer Tom Wilson, heard howling with laughter at the false start of “Bob Dylan’s 115th Dream,” brought in a trusted crew of New York session musicians that included guitarists Bruce Langhorne and Al Gorgoni, pianist Paul Griffin, drummer Bobby Gregg, and film director Spike Lee’s father, Bill, on bass. As Daniel Kramer’s shots from the session show, spirits were infectiously high: the album was the sound of Dylan breaking free of folk constrictions while still delivering acoustic classics in the bracingly nihilistic “It’s Alright Ma” and the closing kiss-off of “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue.” “Obviously Bob liked Elvis Presley and all that,” Sally Grossman said in 2014. “You know, rock and roll was going to be more fun. Plus he was pretty smart, Bob, and how far could he go with that folk music thing?”

As striking as Dylan’s new electric sound was the cover shot for Bringing It All Back Home. The portrait—taken by Daniel Kramer in the sitting room of Grossman’s Bearsville house and featuring a languorous Sally draped across a chaise longue in a red dress bought from a boutique on St. Mark’s Place—made Dylan’s intentions plain. He was no longer the baby-faced faux hobo who worshipped Woody Guthrie; he was a svelte, almost hostile-looking star cradling a gray cat like some James Bond villain.

“COOL” WAS NOW vital to Dylan as he geared up to promote his new record. “Cool” meant not showing your feelings, and it meant medicating them with drugs, foremost among them amphetamine. “Cool” was how Dylan and his inner circle played most of their social interactions, and how Grossman played them too. Some even perceived a kind of three-way dynamic between Grossman, Dylan, and Neuwirth.

“[They] were a very special trio,” wrote Suze Rotolo. “They were very different people and they weren’t really a trio—more like two duos with Dylan in common.” Rotolo witnessed their cruelty when she stayed in Bearsville with Grossman and his wife in the summer of 1965. Dylan was “thin and tight and hostile” and had “succumbed to demons.” It was depressing, she said, to watch the fawning hangers-on “bow and scrape to the reigning king and his jester,” and she saw afresh what a “lying shit of a guy” he was with women. “I think the whole Albert thing was so destructive for him,” Joan Baez told Tony Scaduto in 1971, “and it’s so sad because Albert used to think he was doing right by people, money and fame.” When Scaduto asked if Grossman was “screwing up [Dylan’s] mind” by enabling or even encouraging his truth attacks, Baez replied that “everyone was, around Bobby, because he’s so powerful.”

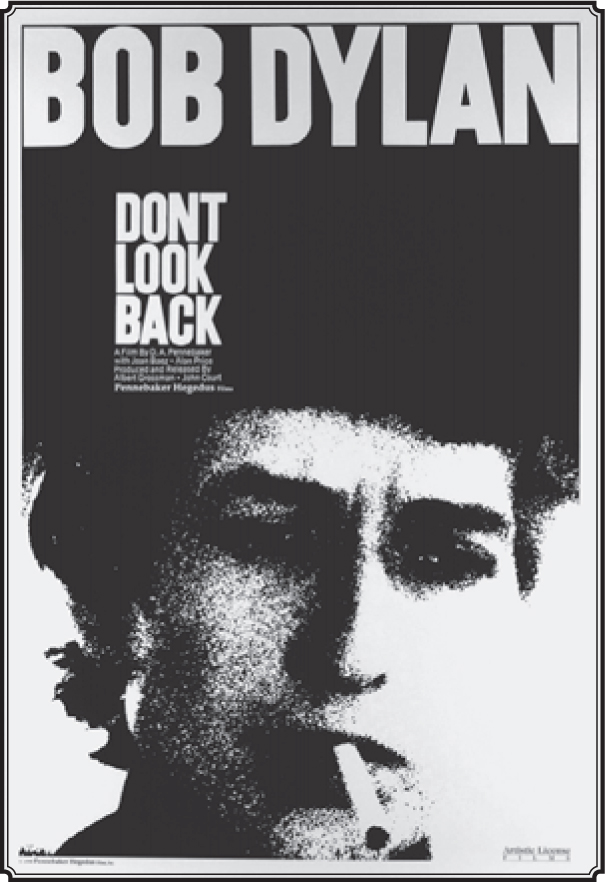

It was Sara Lownds, officially the new woman in Dylan’s life, who arranged for him to see Donn Pennebaker’s 1953 film Daybreak Express. From the screening came the notion of shooting a cinema verité documentary about Dylan’s upcoming tour of England. “I don’t think I was Bob’s choice but Albert’s,” says Pennebaker. “Albert was looking for somebody who had done some filmmaking but who could get into that world. I was going to shoot some stuff, and Dylan would get used to being shot in that style.” Pennebaker warmed to Grossman, who became the same kind of father figure for him that he was for Dylan. “I liked him, and I liked the role he played with Dylan. He went along; he was interested in what happened. He didn’t just sit at a desk and type.”

Pennebaker is all too aware that the resulting film, which became a cult classic after its 1967 release, fixed Grossman in the pop-culture imagination as unsympathetic and charmless—not least when, with Dylan looking on admiringly, he informs the manager of Sheffield’s Grand Hotel that he is “one of the dumbest assholes and most stupid persons I’ve ever spoken to in my life,” adding that “if it was some place else I’d punch you in your goddamn nose.”

“Albert could be very aggressive to people who blocked his way,” says Pennebaker, “but he never was with me.” Interestingly, Grossman didn’t mind how he came across in Don’t Look Back; if anything, he was proud of it. “Once we went down to the Kettle of Fish,” says Pennebaker, “and a woman came up and berated him for a scene in the film. She really was giving it to him, and I was sitting there amazed. Finally she went away, and I said, ‘Albert, I didn’t realize I was messing up your life with that film.’ He said, ‘Don’t worry—it’s never going to be a problem.’ He loved the way we didn’t compromise the film.” For Pennebaker, Grossman’s paternal protectiveness toward Dylan was crucial. “I don’t think people saw Albert as an ogre in the film,” he says. “They just saw him as the way Dylan had to meet the world. Albert kept him from doing things he might have been ready to do.”

In Eat the Document, the disjointed and little-seen film Dylan pieced together about his 1966 European tour, an English journalist asks Grossman if he knows whether his client is enjoying the tour. “We don’t talk to each other like that,” Grossman unsmilingly replies. Profiling Dylan for the Saturday Evening Post that year, Jules Siegel described how, around Grossman, the singer would go “into a kind of piping whine, the voice of a little boy complaining to his father.” In Don’t Look Back, Dylan rarely addresses Grossman, who hovers in the shadows of hotel suites and dressing rooms, only occasionally grunting in a dreary baritone reminiscent of Henry Kissinger. “I came up with a nickname for Albert that stuck,” said Nick Gravenites of the Grossman-managed Electric Flag. “Cumulus nimbus. We called him the Cloud. You could see it—it’s huge, grey and august—but when you went up to touch it, it wasn’t there.”

For anyone who did business with Grossman, Don’t Look Back made for quite a calling card. “It was a groundbreaking, momentous film because of the magic of what was going on with Dylan,” says Paul Fishkin. “You were watching Dylan transitioning into this rock guy, and at the same you gained a little insight into the business side with Albert. You could see a contemporary manager who understood the artist so well while dealing for the most part with people who didn’t. I think Dylan loved that Albert was this killer guy who loved to torture business people.”

Watching the film today, it is clear that Dylan is not only operating within a “huge transparent bubble of ego”—abetted by Grossman and the goading Neuwirth—but deeply bored by the act that’s served him so well for four years. The performances of songs such as “The Times They Are A-Changin” are perfunctory and almost contemptuous. Having reinvented himself on record as an electric performer, he now acts and dresses like the foppish English pop groups making waves in America. In London he buys polka-dot shirts and Anello & Davide boots. He lets his hair grow into a tousled nest and constantly masks his eyes with sunglasses. Amphetamines make him aggressive, and he has tantrums unbecoming in a four-year-old. When his advances toward Marianne Faithfull are rebuffed he yells at her to leave his hotel room.

In a pained letter to her sister in early May, Joan Baez noted that even Bobby Neuwirth was “going mad with it all.” But then it was Neuwirth who delivered the knockout punch when—with Dylan sniggering behind her—he cast aspersions on the size of her breasts. Deeply hurt, she left for Paris the next day. When she returned two weeks later, she learned Dylan’s dirty little secret. After he was admitted to St. Mary’s Hospital in Paddington—he’d been dosed with acid, claims Clinton Heylin—Baez’s knock at the door of his room was answered by none other than Sara Lownds.

“I was just trying to deal with the madness that had become my career,” Dylan disingenuously explained in 2009. “[And] unfortunately [Joan] got swept along and I felt very bad about it. I was sorry to see our relationship end.” Perhaps he should just have sung her the song he’d performed with her so many times: “I’m not the one you want, babe / I’m not the one you need.”