Sir Edward Poynter’s 1881 drawing of the Biblical scene where Moses and Aaron confront the magicians of pharaoh.

To many people today, the most familiar example of an Egyptian magician is Moses. Yes, that Moses, the Old Testament prophet who led the Hebrews from servitude in Egypt to freedom in the promised land of Canaan, giving us the Ten Commandments along the way. For centuries, there was no conflict between the magical prowess of Moses and his role as a wise prophet. Not only was Moshe or Musa (‘Moses’) called upon in Jewish and Christian magic spells into the medieval era, but he features as a sage in the Quran as well. The Book of Exodus tells us that Moses was raised as an Egyptian, and a privileged Egyptian at that. His Jewish birth mother floated him in a basket in the Nile marshes when he was just a baby, to save him from a pharaoh who ordered all the male children of the Hebrews killed. When pharaoh’s daughter found him, she gave him his Egyptian name (‘Moses’ comes from the verb ‘to be born’) and brought him up as her own son. Only as an adult did he realize his true origins. Witnessing the terrible treatment of a Hebrew slave, Moses struck and killed an Egyptian man, then fled the country to escape the punishment of pharaoh, his adoptive grandfather. So much for life as an Egyptian prince.

Sir Edward Poynter’s 1881 drawing of the Biblical scene where Moses and Aaron confront the magicians of pharaoh.

Exodus is first and foremost a story of how the Hebrew god Jehovah used Moses to save the Jewish people from Egyptian oppression. But it is also brimming with tales of ancient magical practice. With his brother Aaron for support, Moses returned to Egypt and secured an audience before the king of Egypt, by that time a different ruler from the pharaoh of Moses’s youth. Show us a miracle, said pharaoh. So Aaron held out a rod and threw it to the ground, where it instantly turned into a snake. The king called his own sorcerers forward. What did they think of this miracle? Not very much, because they knew the same trick. The ground in front of pharaoh soon writhed with reptiles as each of his magicians threw down a wand, only for Aaron’s serpent to eat up the newly sprung snakes, one by one.

Ancient Egyptian literature provides several precedents for this magical confrontation between serpent-wielding sages. Magicians often play a central role in Egyptian tales that combined history, adventure, humour, and moral instruction, and which today give us an important insight into the high status that magicians held in Egyptian society, and how these priest-magicians themselves liked to be seen. Being a magician was a big responsibility. Having magical powers at your disposal could place you at a king’s right hand, but magic could also get you into trouble if not used wisely. Skilled magicians could fly like birds or make themselves invisible, according to the spells we know they had at their disposal. More importantly, they held positions of trust in their communities, helping people at times of crisis and need. Magic wands shaped like serpents really did exist, with a real purpose: to keep dangers at bay in a dangerous world.

Egyptian magic started at the top with the king himself. The Pyramid Texts – those ancient written versions of even older incantations – describe the king as hekau, ‘possessor of magic’. Rather than implying that the king performed magic, this seems to suggest that the king’s whole person had magical qualities. He was, after all, more than human, thanks to his unique relationship with the gods. The servants who came into close contact with the king – such as his barbers and manicurists – had to be equipped, magically, to handle the heka that existed in his body. Shaved-off stubble, hair trimmings, and nail clippings contained some of that magical force and therefore had to be disposed of safely; in the wrong hands, their heka could wreak havoc. No wonder some of these servants earned themselves fine tombs in the courtiers’ cemeteries that clustered around Old Kingdom pyramids.

The Egyptian pharaoh did not necessarily perform magic himself. Instead, he surrounded himself with trained magicians, like the pharaoh of the Exodus story. Tales written down on papyrus, and circulated for hundreds of years, recount the exploits of magicians with royal connections. One series of stories that was written down around 1600 BCE features King Khufu, builder of the Great Pyramid at Giza, who reigned a thousand years earlier. A bored Khufu challenges his sons to entertain him with tales of wonder. In the third of the five stories, Prince Baufre recalls how Khufu’s father Snefru once had his chief reading-priest, Djadjaemankh, use magic to turn a wax boat into a real boat and fill it with twenty gorgeous young women, dressed only in strings (or perhaps fishnets) of shimmering faience beads. Snefru enjoyed the chance to have the women row him around a pleasure lake at the palace, until their boat abruptly stopped: one of the rowers had dropped a fish-shaped pendant into the water. Djadjemankh came to the rescue by stacking one half of the lake upside down onto the other, thus retrieving the pendant. It wasn’t quite as dramatic as parting the Red Sea, perhaps, but it seems to have done the trick for old Snefru – and hearing about it cheered Khufu up, too.

When it’s the turn of Prince Hardedef to entertain his father Khufu, he asks permission to bring a magician named Djedi to the royal court. Djedi is 110 years old, with the appetite of an ox, and such magical prowess that he can tame a lion and re-attach a man’s severed head. Djedi also knows all about the secret chambers in the temple of the god Thoth, which Khufu would like to find so that he can have their magical inscriptions copied into his own temple. Djedi arrives and makes an excellent impression on Khufu and his court. The magician refuses to let Khufu chop off a prisoner’s head just to see if he can reattach it. They settle for a goose instead. Djedi also demonstrates that he can make a lion walk peacefully behind him, without even using a leash, but when Khufu asks the old wise man about the secret chambers of Thoth, Djedi launches into another layered story that instead predicts the rise of a new dynasty of kings, who would be born as triplets to a woman named Redjedet. That wasn’t quite the answer that Khufu was hoping for, but a recurring theme in Egyptian literature is that not even a pharaoh can know all the secrets of the cosmos. Only a magician could even begin to access the wisdom of Thoth, and only with great difficulty and at great personal risk.

In later periods of Egyptian history, a protagonist named Setne featured in tales that emphasized how badly things could go wrong for magicians who came too close to the sacred books in which Thoth had written down all the secrets of the universe. ‘Setne’ was not a personal name but a version of the sem-priest title as it was historically held by the high priests of the creator-god Ptah at Memphis, one of the largest cities in ancient Egypt, near modern-day Cairo. The tales were written down in Demotic during the Ptolemaic and Roman eras, but the high priest in question was one of the eldest sons of King Ramses II, Prince Khaemwaset, who lived around 1280 to 1200 BCE. Khaemwaset was one of many learned, influential priests throughout Egyptian history who were immortalized in literature and remembered as wise men and magicians. However, the Setne stories poke gentle fun at this sorcerer-prince, using him to convey moral lessons about the great responsibility that a great magician had.

Prince Khaemwaset, son of Ramses II and priest of Ptah – the inspiration for the Setne stories.

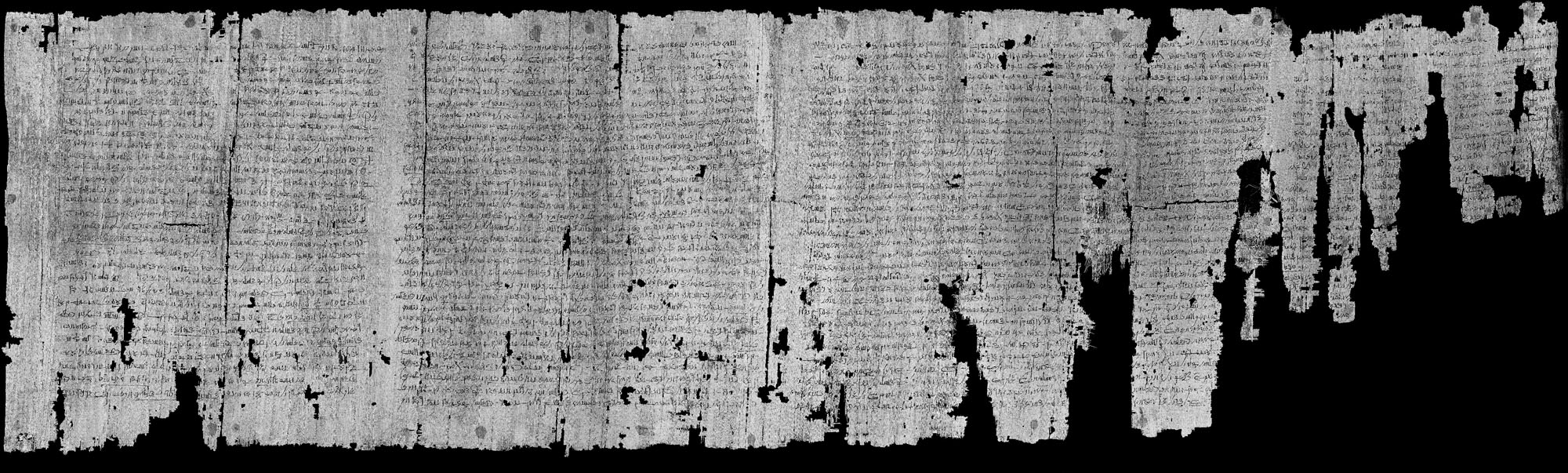

Beginning of a Demotic papyrus scroll with the first Setne story.

In the earliest complete Setne tale, written on a papyrus now held in the British Museum, Setne discovers the tomb of a priest-magician named Naneferkaptah. The tomb is in the cemetery that served Memphis, called Saqqara, where we know the real Khaemwaset undertook restorations to old monuments as part of his priestly duties. In the story, Setne, like Khufu, is on the hunt for the secret book of Thoth, which he has heard is buried with Naneferkaptah. As any ancient Egyptian should have known, trespassing on a tomb was the gravest of crimes, and sure enough, Setne finds himself face-to-face with the ghosts of Naneferkaptah, his wife Ikhweret, and their young son Merab. The ghost of Ikhweret begins to tell their tragic tale to Setne, both to warn him against the folly of seeking the Book of Thoth and to ask his help in reuniting this ghostly family, whose burials – as her story-within-a-story explains – are divided between Saqqara and the southern town of Koptos.

It transpires that Naneferkaptah was a prince and a sorcerer as well (in fact, the Setne tales hint that there were other stories, now lost, that featured the exploits of Naneferkaptah). One day, while Naneferkaptah was fulfilling his duties as a priest, reading from a scroll during a sacred procession, another priest offered to tell him the whereabouts of the Book of Thoth, in exchange for a bribe. Naneferkaptah can’t resist, and having extracted the information from his colleague, he convinces Ikhweret to sail with him up the Nile to Koptos with their son. At Koptos, Naneferkaptah makes a boat and crew out of wax, recites a spell to animate them, and sets sail for the secret book’s hidden location. When he reaches the point that his colleague described, Naneferkaptah casts sand into the water to divide it in two. He fights his way past the snake that guards the book, cutting it in half and putting sand between the severed pieces so that it cannot come back to life. Evil reptile defeated, Naneferkaptah works his way through the layered boxes that conceal the book: first iron, then bronze, wood, ebony and ivory, silver, and finally a box of pure gold with the papyrus scroll inside.

Eagerly, Naneferkaptah takes hold of the scroll and unrolls it, reading its spells and so gaining the ability to enchant all of nature. He sees a vision of the sun-god Ra shining in heaven and, at the same time, the rising of the moon and the stars. Magic, he understands, is what controls the cosmos, and Naneferkaptah, a magician and a prince, but nonetheless a mere human, now has power over it. He returns to his wife Ikhweret, hands her the book, and she – a princess and an educated woman – also reads the spells and has the same wondrous experience as her husband. Naneferkaptah uses fresh ink and papyrus to make a copy of the scroll, and soaks the copy in beer. He then dissolves the soggy scroll in water and drinks it, imbibing the magical texts into his own body. This consumption of magic words and images was a core component of Egyptian magical practice.

When Thoth discovers that Naneferkaptah has taken his secret book, he complains to Ra about the grave offence. This is the warning, and the plea, that Ikhweret presents to Setne: having knowledge that you should not possess is deadly. As she and her husband start their homeward journey downriver, their boat suddenly stops, and their beloved son Merab falls into the river and drowns. Not even Naneferkaptah can bring him back to life, so they return to Koptos to have the child embalmed and bury him there. Setting out a second time, in a more sombre mood, their boat is once again halted in the same spot. Ikhweret falls into the river and drowns, and her husband has to repeat the sorrowful return to Koptos, where he has her embalmed and buried with their son. The third time he prepares to sail forth from Koptos, Naneferkaptah takes a strip of royal linen, binds the Book of Thoth to his body, and waits for the inevitable to happen. When the boat stops, Naneferkaptah appears on deck and falls into the river, but his body can’t be found. The boat sails on without him, and when it arrives at the docks in the Memphis, the king and court come to greet it, in mourning. Pharaoh spies Naneferkaptah, dead but magically holding fast to the boat’s rudder, with the Book of Thoth still tied to his body. He orders a fine burial for Naneferkaptah in Saqqara, and has the deadly scroll hidden away within it.

Hearing all of this from the ghost of Ikhweret, Setne knows the danger that awaits him – but he ignores her warning. Setne manages to get the Book of Thoth away from Naneferkaptah and takes it to the pharaoh’s court, where he reads the magic that it contains. As Ikhweret predicted, Setne is soon plagued with misfortune. He falls in lust with a beautiful priestess named Tabubu, who refuses to sleep with him unless he signs over all his worldly goods to her and disinherits his own children. Drunk on wine and sexual desire (a betrayal of his priestly responsibilities), Setne agrees. He falls into a deep sleep, and sees his children murdered and fed to dogs. When he wakes to find himself naked, shivering, and alone, he wonders what he has done.

Fortunately, it was all a dream – or a nightmare – and a chastened Setne returns the Book of Thoth to the tomb of Naneferkaptah. The tomb-owner’s ghost thanks him and asks a favour, which Setne gladly undertakes, now that he is back on the priestly path. Setne sails to Koptos and searches its cemeteries for three days and three nights, until he finds the tomb where Ikhweret and Merab were buried all those centuries ago. He brings their mummies to Saqqara and buries them in the tomb with Naneferkaptah. It’s as close to a happy ending as any magician could hope for.

These sets of stories reveal the status of magic in ancient Egypt: magicians were welcomed at the royal court and granted privileges, like the fine burial arranged for Naneferkaptah. They also help us understand what kind of people practised magic: Djadjemankh was a chief reading-priest, as from the sound of it was Naneferkaptah, while Khaemwaset was a sem-priest and good old Djedi seems to have had no title at all, but a reputation that reached the ears of a prince. Finally, they show us specific examples of magical techniques, such as the conjuration of a boat and its crew, and the sources of magical knowledge, such as the secret books and chambers of Thoth. These may be tales of wonder, which we would file under fiction today, but they were telling some magical truths.

From princes to paupers, what most magicians in Egypt had in common was their membership of a priesthood. Magic was never really just entertainment for bored kings. It was linked to the supernatural world of the gods, and thus to the everyday world of the Egyptian temple. Temples were a crucial vehicle of the Egyptian state. They owned agricultural land and livestock, as well as running workshops for the production of all kinds of commodities, from works of art to food, textiles, and burial equipment. They organized religious festivals, kept archives and libraries, and helped monitor the Nile to gauge the all-important annual flood as it swelled the river from south to north each summer.

Egyptian temples ranged from vast complexes that dominated the surrounding landscape to more modest compounds in small villages. Regardless of their size, however, every temple needed priests. Most priests came from leading local families, and as there was no restriction on priests having wives and children, priestly positions tended to be handed down from father to son (as was the case with most occupations in ancient Egypt). Priests had to be able to read and write, so as children, they might already have attended temple-based schools.

Being a priest wasn’t necessarily a full-time role. It could be combined with other responsibilities, such as owning and running an agricultural estate. Large temples divided the priesthood into four or five groups that worked in rotation, each looking after the temple rituals and other business for two or three months of the year. During that period, priests were meant to follow restrictions on what they ate and how they dressed, and may have lived in the temple to help maintain the required state of purity (which included observing sexual abstinence). In smaller temples, with a smaller population to draw on, these rules and rotas may have been more flexible. Nor should we imagine that when a priest wasn’t officially on duty in the temple, he was completely off duty in his daily life. Once everyone knows that you have a level head, or a sympathetic ear, it’s difficult to pass a petitioner on to whoever happens to be in charge at the temple that month. The same held true if your priestly path meant that you’d gained a reputation as an accomplished magician or talented healer.

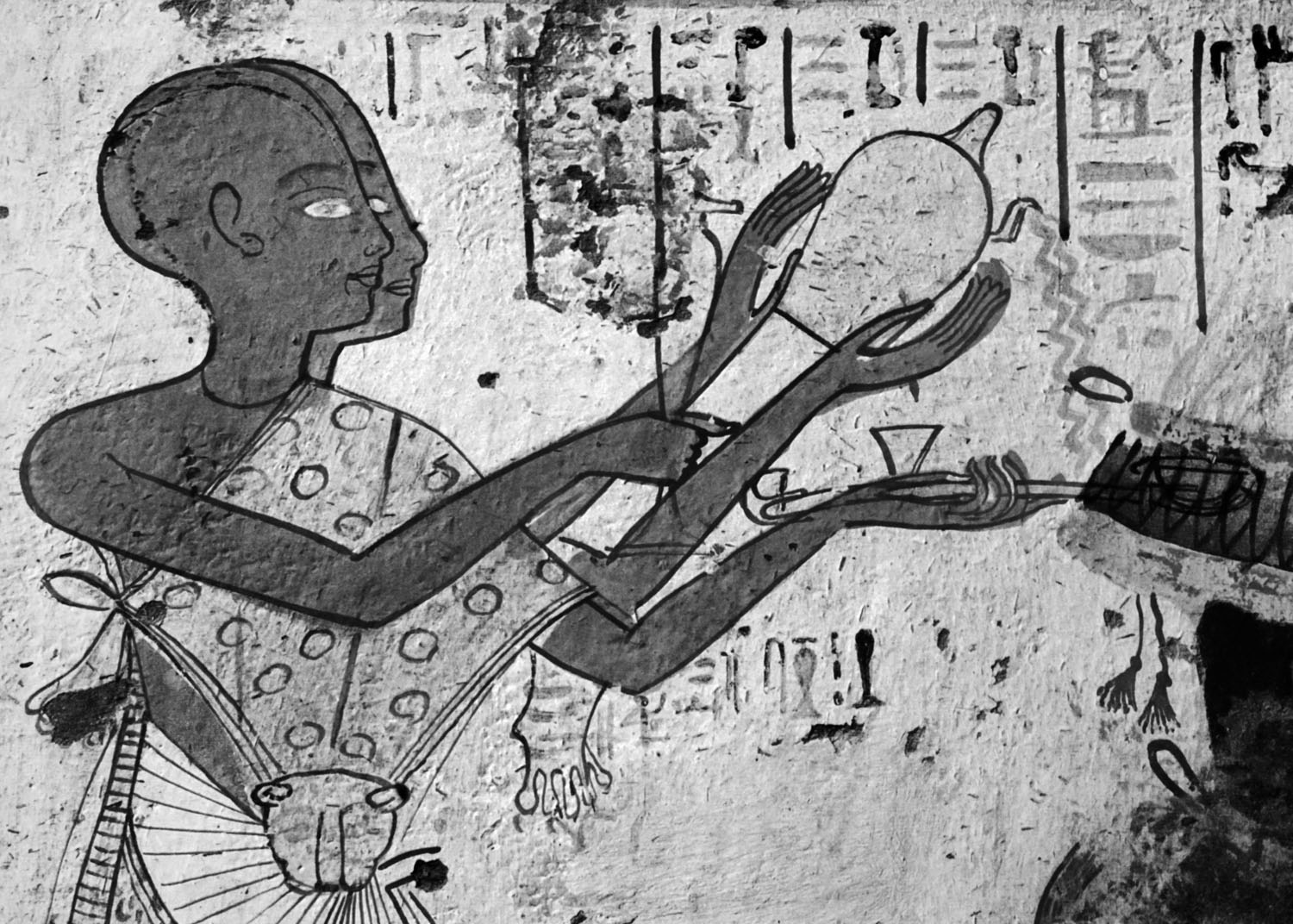

Magic rituals and temple rites have many things in common, which means that almost every priest in some way came into contact with heka in the course of carrying out his temple duties. But only certain priests specialized in magic. This reflects the division of the priesthood into different types or categories. One category of priest closely associated with magic was the sem-priest, like Setne. The sem was a role that a priest or other individual of rank took on for certain ritual performances, and the sem is easily identifiable in art by the leopard skin draped across his body. Sem-priests officiated at a ritual called ‘Opening the Mouth’, which was performed to bring a living spirit into the body of a finished statue or an embalmed mummy.

Sem-priest in a leopard-skin, with vases of cleansing water and an incense burner.

The priest most closely associated with magic was the khery-heb, or reading-priest; some, like Djadjaemankh, attained the higher rank of chief reading-priest. Egyptologists usually term these men lector priests, from the Latin word for reading. In ancient Egyptian, khery-heb meant ‘carrier of the scroll’, and in visual representations of the reading-priest at work, he is often shown reciting from a scroll of papyrus that he unrolls between his hands. The khery-heb was someone especially learned and literate, who had full access to the libraries of texts that temples held. Perhaps the reading-priest also had a special gift for chanting these texts during rituals, since speaking the rites, as we’ve seen, was as important as being able to read them.

The sem and the khery-heb worked in the service of a whole range of gods and goddesses in temples all over Egypt. But there was one goddess whose priesthood had specific magical expertise: the wab-priests of the goddess Sekhmet specialized in healing. Wab, meaning ‘pure’ or ‘clean’, was a relatively lower rank of priest, but Sekhmet was a fitting focus for this type of magical specialism – this lion-headed goddess was believed to have power over illnesses that had no obvious physical cause. We now would identify many of these illnesses as infectious diseases caused by bacteria, viruses, or parasites, but in ancient Egypt, such afflictions seemed to strike from nowhere and, even worse, spread among families and communities. Supernatural causes were the natural explanation, and priests of Sekhmet were thus best equipped to help with medical complaints – both in Egyptian mythological thought, and in our own terms of practical hygiene.

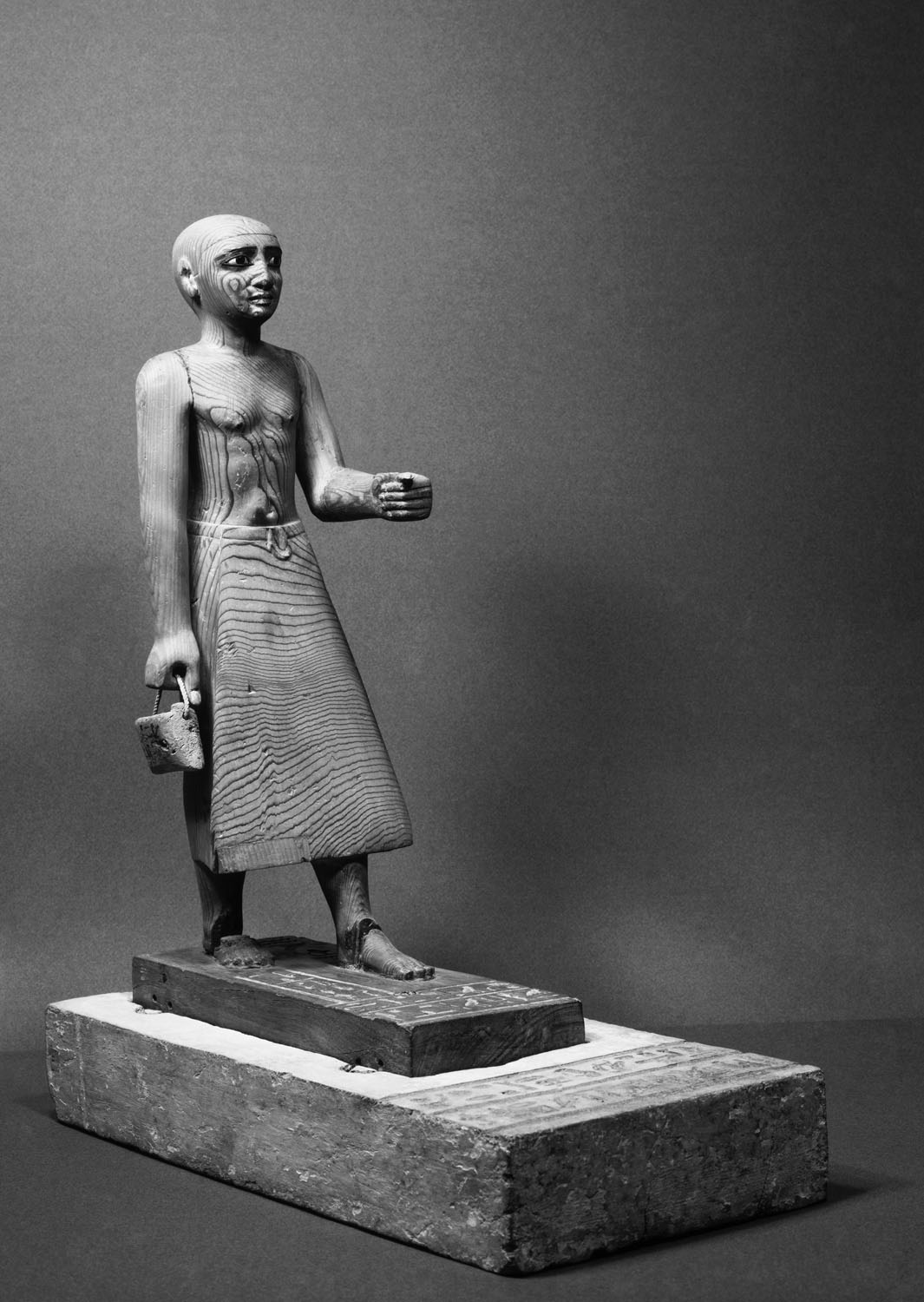

Wooden statuette of Djehutyhotep, leader of the hekau (magicians).

Another class of magicians with a specialization were scorpion- charmers, known as the kherep of Serket (or Selket), the goddess associated with scorpions. A kherep was a sceptre or wand, which as a hieroglyph symbolized having power over something. Hence the kherep of Serket was someone who had power over scorpions. These specialists are often found listed among the personnel of state-sponsored mining expeditions that had to face the dangers of travelling across deserts, home of scorpions and other deadly creatures.

There are two general terms for magical specialists that don’t seem to link the practitioner to a specific deity or priesthood. One was rekh-khet, ‘knower of rites’, and the other simply hekau, the same expression – ‘possessor of magic’ – that had been used in the Old Kingdom to describe the king. By the Middle Kingdom (a few hundred years later), it seems to have become a more general term for a magician. A wooden statue representing a man named Djehutyhotep identifies him as ‘leader of the hekau’, as well as a scribe, and the bag that he holds in his right hand may be a container for some of the equipment he required in his line of magical work.

That equipment will have included amulets, either made by Djehutyhotep himself or by special amulet-makers called sau, after the word sa, meaning both ‘amulet’ and ‘protection’. Like hekau, the term sau is used broadly. Some amulet-makers were probably magicians themselves. They may have been attached to temple workshops, where amulets in materials such as faience, glass, metals, and semi-precious stones were often made. At certain times in ancient Egyptian history, the circulation of these materials was restricted, especially where unusual technologies or rare materials were involved. Getting your hands on a carnelian tyet-amulet or a faience wadjet-eye required the right connections.

Producing faience, shaping glass, and casting bronze all required specialist knowledge and equipment, and making amulets out of these materials was a form of magic in itself. Invented as early as 3500 BCE, faience is a material the ancient Egyptians called tjehenet, from the word for ‘shining’ or ‘luminous’. Similar to glazed pottery (but without the inclusion of clay), faience was made from a paste of ground quartz, which included silica particles, with plant ash, natron salt, and copper ore; when fired in a kiln, the silica and copper in this dull mixture fused into a glossy blue-green surface, which looks almost like a polished stone. Early glass technology, which developed much later, around 1600 BCE, required even more control of silica and minerals that provided colouring agents, while casting bronze and other metal alloys was its own skill, and one for which the ancient Egyptians were well-known in the ancient world. Today we would explain these transformations of raw materials by chemistry, but in antiquity they worked by, and like, magic.

Many amulets were made of much simpler materials, as we saw with the linen and papyrus amulets in the last chapter, which the magician could make on the spot for his client. The magical effect of amulets made of knotted cloth, or tiny folded packets of papyrus, lay in the words that were written on them, spoken over them, or both. Scorpion-charmer or amulet-maker, khery-heb or plain old hekau, there were clearly many ways to refer to magicians in ancient Egypt, not all of which map easily onto modern terms such as wizard, sorcerer, or healer. Nor, as you might have noticed, have we mentioned a witch or a sorceress, since what is missing here is approximately half the population: the women.

Though not well attested in ancient texts (which were written, for the most part, by and for men), women almost certainly had their own ways with magic in ancient Egypt. However, the female version of hekau, spelled hekat, is only ever used in a derogatory way, to describe a female magical practitioner who wasn’t considered Egyptian; in that sense, it means something like witch, with a negative connotation. What does survive from ancient Egypt are a few references to female magical practitioners or wise women, using the word rekhet, ‘she who knows’, similar to the expression rekh-khet for a male magician. Letters written in the Old and Middle Kingdoms suggest that these wise women could contact the dead. We can also take it for granted that women helped other women give birth, since midwifery is such a common practice across human societies. As we’ll see in Chapter 6, childbirth came with its own set of magic rites. Women were not full-fledged magicians, according to the hierarchy of the Egyptian temple, but they nonetheless performed magic of a different sort, when only a woman’s touch would do.

In the hierarchy of Egyptian priesthoods, magicians belonged to the temple’s ‘House of Life’ (per ankh). The House of Life was both a place – a sort of library and learning centre – and a social institution, like a club or brotherhood to which magicians and other important priests belonged. Its influence lasted as long as the temples did, into the Late Roman period and beyond. The House of Life was an earthly version of the secret chambers of Thoth, full of wisdom and knowledge that could serve society beyond the temple walls. In the House of Life, it was the life of the community that was at stake: its heritage, its memories, and its health.

Priests who trained and served together in the House of Life formed close bonds. Close enough that in the 4th century BCE, the priests of the cat-goddess Bastet at a temple in the Delta clubbed together to erect a special statue in the form of a pious priest, in honour of three of their colleagues: Padimahes, Pasherimut, and Pasheribastet. These three men were not necessarily magicians, according to the titles they held, but they must have had some qualities that made them deserving of a statue, and in particular a statue like this one. For like similar statues known from other temples in Egypt, this statue played a special role in the life of the temple and its local community: it was a magical statue, used for healing and protection and, we think, available to anyone who came to the temple for help. It may originally have stood in a courtyard in front of the temple, perhaps in a small chapel of its own; the inner rooms of the temple itself were always off-limits to anyone other than the priests.

There are two clues to the statue’s function: first, the inscriptions that cover almost every inch of its surface, and second, the object that the priest is holding between his hands. Carved from a form of sandstone known as greywacke, the statue is exquisitely made and highly finished. Its dark, polished surface is incised with magical images and hieroglyphic spells, from the cloth kerchief that covers the priest’s head to the edge of the ankle-length garment he wears. The calm, noble-looking figure, with his left leg forward in the stance typical for statues of men, is probably a generic stand-in for all three of the priests that the statue honoured, who appear individually across the statue’s abdomen, carved in recessed relief, in the act of praying to Bastet and her son Mahes, a lion-headed war god.

Between the hands of the statue is a stela, or cippus, showing a deity called Horus-on-the-crocodiles, for reasons that quickly become obvious. Hundreds of such objects survive, in every size, from wearable pendants, to amulets that would fit in a hand to sizeable standalone sculptures (see page 118). The central image on the front shows the god Horus as a child, standing on the aforementioned crocodiles and grasping reptiles and wild animals in his hands. The scene represents his magical mastery over dangerous forces, and many of the magic spells written over the statue’s surface use stories of Isis and young Horus to repel the effects of snake bites and scorpion stings. Other spells, together with the emblems carved alongside them, have a more general protective function. They tie the statue and the Horus image into the astral powers of the cosmos and creation.

Dark stone statue honouring three priests of Bastet, with a healing stela of Horus-on-the-crocodiles.

Statues like this one, or a Horus stela on its own, worked by using sacred water to absorb magic words and images – which were, after all, the same thing, given the pictorial character of hieroglyphic writing. Just as, in the Setne story, the magician Naneferkaptah dissolved a copy of the Book of Thoth first in beer and then water and drank it, the water poured over the surface of a magical statue or stela would absorb the power of the hieroglyphs. Cups or basins placed below would catch the energized water, which took on healing properties. Or at least, that’s what visitors to these statues must have hoped.

Not coincidentally, perhaps, the water running over the front of this statue also covered the personal names and incised images of Padimahes and his fellow priests. We can tell by their names that the three men were all local boys: Padimahes means ‘The child given by Mahes’, while Pasheribastet is ‘The child of Bastet’ and Pasherimut is ‘The child of Mut’, another goddess worshipped nearby. So it may be that in helping to bless the water to help local people, the statue was also helping to bless these men, as well as commemorate their memory for as long as the statue stood. Adventure stories weren’t the only way that the reputations of wise priests, gifted healers, and talented magicians were preserved. Through statues, monuments, and their family tombs, priests and magicians became part of the Egyptian landscape, their names, feats, and memories passed down through generations.

But how did men like Padimahes and his colleagues become priests – and potentially magicians – in the first place? The ability to read and write was essential, so training in magic began, for boys, in the scribal schools situated in temples throughout Egypt. The rare women who acquired this skill probably did so at home, from male relatives. But being able to read and write wasn’t enough to get you into the priesthood, much less make a magician out of you; as we have seen, priestly roles often ran in families, and having connections may have been as much, if not more, important than natural ability when it came to joining a certain priesthood. Lineage mattered in ancient Egypt.

Many of the things a magical expert needed to know could probably only be learned through in-person observation, and one-on-one apprenticeships would surely have served to protect the secrecy that so many rites required. Finding and using magic materials, learning the correct gestures to use, and hearing the right words, spoken in the right way, were things a would-be magician could only learn from a master. And the magic spells collected in the Pyramid Texts, the later Coffin Texts, and the Book of the Dead (which the Egyptians called the ‘Book of Going Forth by Day’) may give us a glimpse into some of the tests that priests and magicians had to pass to demonstrate their proficiency once their training had been completed. Some form of initiation, known as ‘seeing the horizon’, seems to have marked a priest’s formal entrance into service, once a trainee had acquired sufficient knowledge to perform rites safely and could be trusted by his fellow priests to fulfil his duties independently.

The judgment ceremony in the Book of the Dead, known by scholars as spell (or chapter) 125, may be based on just such an initiation rite. In this scene, the heart of the deceased is weighed against the feather of truth (maat), so that they can join Osiris in the underworld, as long as they are judged worthy; they then became known in ancient Egyptian as ‘true of voice’, often translated as ‘justified’. In the judgment spell, the deceased – perhaps originally, the priestly initiate – declares his (sometimes her) purity, honour, and virtue, the same qualities that Setne temporarily abandoned in his lust for Tabubu. Other bad behaviour that had to be denied included eating unclean foods, having illicit sex, fiddling your account books, and stealing from the temple’s cattle herds.

The judgment scene from the Book of the Dead made for Ani and his wife Tutu.

Like the judgment scene, many other spells in the Book of the Dead seem to originate from the secret knowledge kept in the House of Life. In the context of a burial, where they were written on papyrus or painted on coffins and tomb walls, such scenes and spells take on a double layer of meaning. Spells for becoming a bird, having power over the elements, and joining the boat of the sun-god express the dead person’s hope of an empowered life in the next world – that ability to ‘come forth by day’ from the darkness of the tomb. But they also reflect the kinds of ritual knowledge that only priests could possess, and some of the powers that magicians could wield. Over time, these powers included fantastic abilities such as flying (if you’re a bird, you’re halfway there) or becoming invisible, as was the purpose of this tantalizing spell from Roman times:

Take a falcon’s egg. Gild half of it and coat the other half with cinnabar [red mercuric sulfide]. While wearing this, you will be invisible when you say the name.

Unfortunately, the writer has neglected to indicate what exactly that name would be, although we’re assured that the spell is both ‘marvellous’ and ‘practical’. No wonder ancient texts sometimes baffle our uninitiated ears and eyes.

But knowledge was power. An experienced priest-magician will have internalized an astonishing array of information as part of his training, from the manifold names of deities, demi-gods, and demons, to the plants and minerals that were the core ingredients in healing concoctions and protective potions. In the judgment of the dead, give the wrong answer and your cheating heart would be eaten by the monster Ammut, condemning you to a state of powerless non-being. For magicians passing from their training days to full-fledged practice, just as much was at stake for themselves, their clients, and the entire cosmos. The natural and the supernatural worlds were intertwined, like the world of the living and the world of the dead – and a magician needed to know how to handle both.