Wall painting of Egyptian priests at a Roman Isis temple, from the town of Herculaneum, Italy.

The fate of the Dendera zodiac was not the first instance of Europeans interfering with ancient Egypt’s sacred knowledge. Roman emperors had already tried to ban Egyptian temples from the city of Rome, restrict the privileges of priest-magicians in Egypt, and, in early Christian times, stamp out the Bes oracle at Abydos. The high esteem in which Egyptian magic has been held, from ancient times to the present day, has always been both a blessing and a curse.

Many of the magic spells in this book were written down in the last few centuries of Egyptian history, that is, before the rise first of Christianity (from the 3rd century CE) and then Islam (from the 7th century CE). From around 350 BCE, not long before its conquest by Alexander the Great, Egypt was part of a well-connected, predominantly Greek-speaking world that encompassed the eastern Mediterranean, North Africa, and much of modern-day Turkey and the Middle East. Egypt was a multicultural, multilingual society, which had an impact on how magic was practised, as well as the social status of magicians and priests. It also influenced how Egyptian magicians were remembered in medieval, early modern, and modern times, both in the Arab-speaking world and in Western Europe.

This final chapter considers some of the changes in Egyptian magic that took place in Roman and early Christian times and how, from there, ideas of Egyptian magical prowess and secret wisdom took hold in Europe. In the wake of the French invasion of Egypt in 1798, which targeted the country for colonization, the study of ancient Egypt gradually developed into the academic field of Egyptology. Egyptology by and large rejected esoteric engagements with ancient Egypt, but in the late 19th and 20th centuries, many people embraced the opportunity to keep Egyptian magic, as they saw it, alive. This continues to be true today, from Kemetic churches that worship the ancient gods to theories about astrology and pyramid power, to the use of Egyptian symbols as personal talismans or commercial trademarks. The mystique of magic floats many people’s boats. Perhaps Ra and Thoth, Isis and Horus, and wise old Imhotep are all happy to go along for the ride.

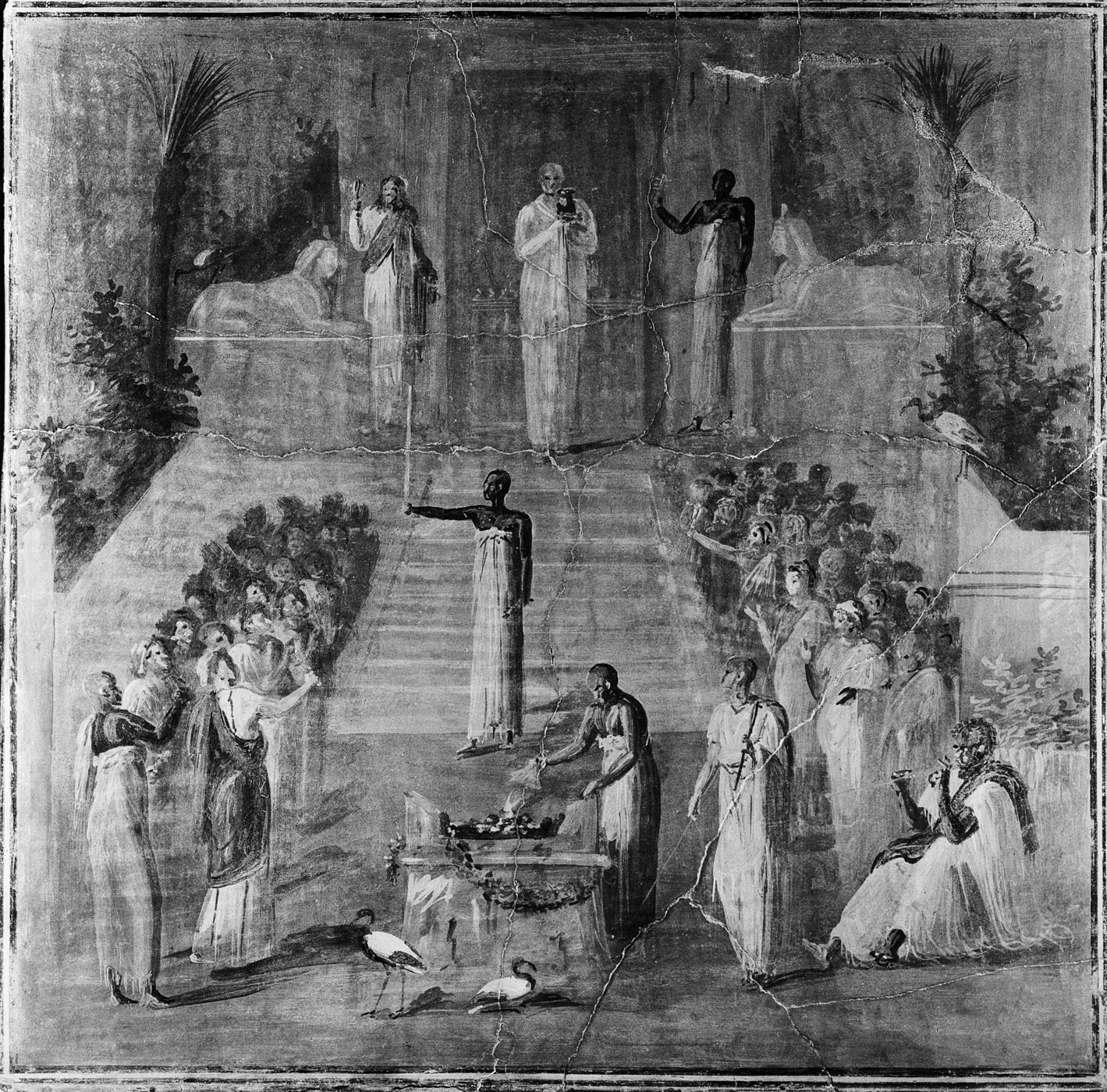

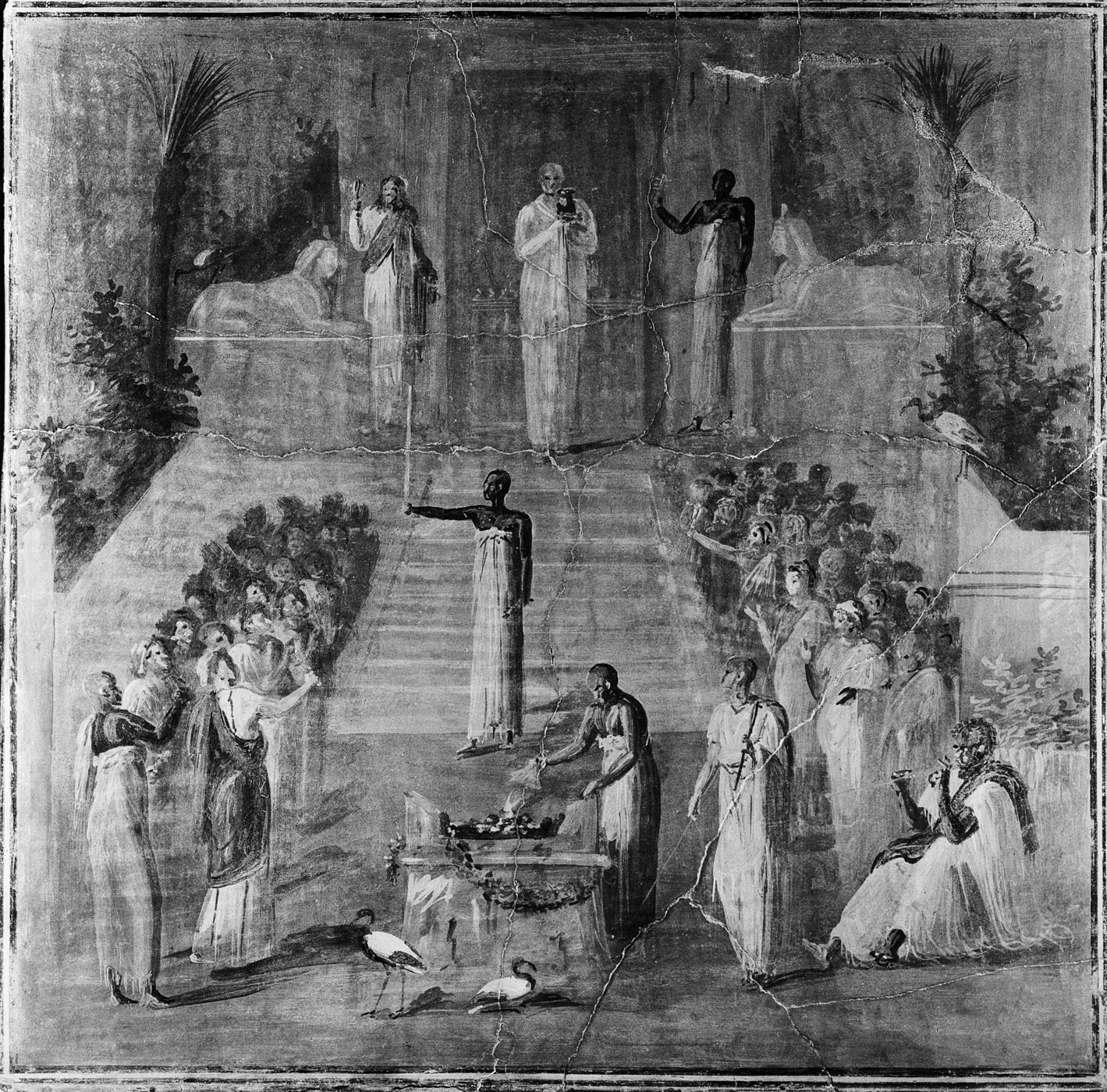

From the 4th century BCE onwards, as Egypt became more closely connected to its Eastern Mediterranean neighbours, the worship of Egyptian gods began to spread beyond Egypt, first to Greek islands and later to the Italian peninsula. And wherever the Egyptian gods went, Egyptian priests – and their magic – went with them. Before long, temples dedicated to Isis, the Great Lady of Magic herself, could be found right across the Roman world. A painting from the town of Herculaneum, near Naples, which was buried by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 CE, depicts some of the Egyptian priests who served at her temple there. They are easily recognizable by their stereotypical appearance: they wear the long white garments and shaved heads that had symbolized the personal purity required for Egyptian temple service for millennia.

Some Roman authors twisted those bald pates into a source of mockery, in stories and novels where an Egyptian priest or magician was exposed as a fool or trickster. Roman writers had a vested interest in making Egypt seem stranger or less civilized that Rome, in part to justify Rome’s annexation of Egypt and to define such supposed Roman virtues as order, plain living, and civic or military virtue. This doesn’t seem to have ruffled the feathers of the ibises that strolled the grounds of all the Isis temples in Italy. And there were plenty of authors, especially those writing in Greek (rather than Latin), who admired Egypt and wrote positive accounts of the country’s long traditions of learning, wisdom, and, indeed, magic. Some of the tales of Setne may have been translated into Greek, in fact, since a similar character, named Kalasiris, features in a novel by the Greek writer Heliodoros, perhaps written in the 3rd century CE. Like any Egyptian priest-magician worthy of the title, Kalasiris has secret knowledge in spades, but he plays his cards close to his chest.

Wall painting of Egyptian priests at a Roman Isis temple, from the town of Herculaneum, Italy.

In Egypt itself during the Roman era, priests and magicians were no laughing matter. They were in many ways the last bastions of the country’s most ancient traditions, including its language. The last surviving hieroglyphic and Demotic inscriptions were composed by priests of Isis on the island of Philae in the 4th and 5th centuries CE respectively. At Philae, as well as the temple of Horus at Edfu around this time, it seems that a sacred falcon was kept in a large cage over the temple gateways, suggesting that animal magic still had an appeal. But the influence of Rome saw many changes occur in Egyptian society, which inevitably affected the roles played by temples and priests. For one thing, changes in taxation meant that temples, which had often enjoyed exemption under the pharaohs, lost much of their economic power. For another, there was a degree of competition from newfangled faiths, such as Mithraism and Christianity.

By the 4th century CE, the old Egyptian gods and their magic ways belonged to a shrinking circle of specialists. Places of worship were abandoned for lack of money, or lack of interest, and some priest-magicians took to the road, itinerant sorcerers who offered their services where they were wanted. Like the reading-priests and scorpion-charmers of old, these travelling magicians could offer amulets, healing spells, and words of wisdom, but in contrast to the traditional mode of worship, where gods and goddesses inhabited fortress-like temples, served by fleets of priests, magic now offered access to portable divinity.

This may be one reason for the increased use of magic gems. Carved in hard, semi-precious stones like jasper, carnelian, and amethyst, whose colours were integral to their power, these gems were used in combination with a recited spell to invoke the presence of a deity, imbuing the gem with the same power as a full-size statue. The gems were incised with imagery similar to that drawn on or described in papyrus manuals of magic, such as scorpions, crocodiles, and a snake swallowing its own tail. But new images appeared as well, in particular a rooster-headed figure with an armour-clad torso and snakes for legs. This figure is sometimes known as Abraxas, after the series of Greek letters often carved on the same gem. These letters were typical of the so-called ‘magic characters’ used at this time, which look like gibberish but could be pronounced by a trained magician to cast a powerful spell. Magic characters were sometimes written in geometric shapes or spirals, too, creating visual puzzles in which letters were added or dropped for effect. If Abraxas seems to ring a bell, you might be experiencing déjà vu from your previous life as an ancient magician. Or you might just recognize it from the magical incantation it eventually inspired: Abracadabra.

Magic gem carved from jasper, showing Serapis (a Greek form of Osiris), a scorpion, a crocodile under the god’s feet, and a mummy on a lion-headed bed.

The same Greek and Egyptian milieu that gave us ‘Abracadabra’ yielded yet another permutation of the wise priest, a man so gifted with magic and secret knowledge that he was nearly divine: Hermes the Three-Times-Great, or Hermes Trismegistos in Greek. This Hermes was a human version of the Egyptian god Thoth, and was credited as the author of magic manuals and wisdom books that originated in Egypt and circulated throughout the Mediterranean during the Christian era. Hermes Trismegistos had a tremendous influence on medieval and early modern beliefs that Egypt was the home of magic, both in Europe and in Arabic-speaking North Africa and the Middle East. Thanks to Arabic interest in his (attributed) writings, Hermes Trismegistos was famous from southern Spain to Central Asia. As a wise man with no particular religious identity, his wisdom appealed to people of many faiths. In Christian Europe, Hermes the Three-Times-Great was thought to be a contemporary of that other great magician, Moses. He is depicted in the impressive 15th-century stone floor of Siena Cathedral, bringing his wisdom to the ancient Egyptian people, wearing attire inspired by Renaissance interpretations of Byzantine art.

One of the great feats of magic that Hermes Trismegistos was thought to have mastered was alchemy, the mystical trick of turning base metals into gold. Alchemy – the word itself comes from the Arabic for ‘in the Egyptian manner’ – was a serious intellectual and academic pursuit for centuries. The great Isaac Newton, founding member of the Royal Society in London, was an ardent alchemist. In 17th-century England, his alchemical experiments were just as much a part of ‘natural philosophy’ (as scientific research was then known) as his studies of force and motion. Alchemy was part of the tradition of European thought that informed the 18th-century Enlightenment, although it was later rejected as overly esoteric.

Stone pavement in the cathedral of Siena, 1488: Hermes Trismegistos brings wisdom to Egypt.

Part of a philosophical tradition known as Hermeticism, or Gnosticism, alchemy was not just the search for a key to material transformation, but a path to spiritual transformation. As such, it was embraced by self-styled secret societies, including the Rosicrucians and, to some extent, the Freemasons, both of whom are still active today and both of whom have used ancient Egyptian symbols in the construction of their identity. The Ancient Mystical Order Rosae Crucis (a branch of Rosicrucianism) has its headquarters in San Jose, California, in a park that includes an Egyptian-style museum of Egyptian antiquities and a planned new museum dedicated to alchemy.

In the 19th century, when academic Egyptology set out to define itself as a serious scholarly pursuit, it rejected outright any idea that ancient Egyptian magic really worked or that Egyptian wisdom could tell us anything today. Most Egyptologists approached their subject matter with dry dispassion, even disdain, as if all those scorpion-charms and snake-oil recipes were just too much to bear. At the same time, alternative interpretations of Egyptian magic found new adherents ready to adapt ancient belief systems to modern times. The Theosophy movement, founded by the Russian writer Helena Blavatsky, was one of several esoteric philosophies that flourished in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. These schools of thought combined elements of South and East Asian religions, chiefly Hinduism and Buddhism, with Hermetic-inspired beliefs in self-realization and secret wisdom that had been revealed to gifted individuals through history. Blavatsky summarized her philosophical thesis in a book called Isis Unveiled, whose title gives an indication of the lineage she wished to claim for her ideas. What Isis thinks of the rather long-winded tome has not been recorded.

A contemporary esoteric group that had links to Theosophy, Freemasonry, and Rosicrucianism was called the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn. It was organized into temples of Isis-Urania and Amun-Ra and sought to revive magic rites from the distant past, mixing them liberally with astrology, alchemy, and tarot-reading, none of which really had any roots in ancient Egypt. The London chapter of the Golden Dawn, established in 1888, proved to be a social hub whose members at various points included the writers Olivia Shakespear, Edith Nesbit, and Bram Stoker, the poet W. B. Yeats, and Irish revolutionary Maud Gonne. Golden Dawn’s most infamous member was Aleister Crowley, a divisive figure during his brief association with the London chapter in the late 1890s. Yeats loathed him, but Crowley soon moved on to new pastures. He travelled to many countries, Egypt among them, developing his own occult following and publishing copious books of his own ‘wisdom’ – including an Egyptian-inspired tarot guide called The Book of Thoth.

Briefly entangled with the Golden Dawn, with its longing for lost wisdom, was a young man named Battiscombe Gunn. Gunn’s interest in ‘Oriental’ languages, including ancient Egyptian, seems to have brought him into the group’s orbit, at a time when Crowley was still involved. In 1906, Gunn published a translation of a Middle Kingdom papyrus in the collections of the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris, on which was written a wisdom text called ‘The Instructions of Ptahhotep’, a series of maxims passed down by a long-ago sage. These ‘instructions’ are not magical, but convey the standards of behaviour that were expected of priests and other high-status men in Egypt in language laced with mystical symbols: ‘The inner chamber is open for the one who keeps silence’ encourages the well-known benefit of guarding your secrets through reference to the importance of secret chambers, and secret knowledge, in Egyptian society.

In the introduction to the translation, which was published in a series called The Wisdom of the East, Gunn mused somewhat poetically on what archaeology can – and can’t – convey to us about the ancient world:

Archaeology, is, for those who know her, full of such emotion.…Her eyes are sombre with the memory of the wisdom driven from her scattered sanctuaries; and at her lips wonderful things strive for utterance. In her are gathered together the longings and the laughter, the fears and failures, the sins and splendours and achievements of innumerable generations of men; and by her we are shown all the elemental and terrible passions of the unchanging soul of man, to which all cultures and philosophies are but garments to hide its nakedness; and thus in her, as in Art, some of us may realize ourselves.

Years after he left the Golden Dawn, Gunn pursued a career as an academic Egyptologist, studying and working in Berlin, Cairo, Philadelphia, and Oxford. He repudiated his early translation of the Ptahhotep papyrus, embarrassed by its amateur effort but also, presumably, by his admission that ‘some of us may realize ourselves’ in the quest to understand the ‘unchanging soul of man’. Studying ancient wisdom for personal enlightenment was not what a serious scholar was meant to do, and in later life Gunn opposed mystical interpretations of ancient Egyptian thought.

For decades, only a dispassionate approach to magical texts would do, as scholars tried to separate ‘magic’ from ‘medicine’, or the irrational from the rational. That meant separating Egyptian spells from Greek ones, even where they were written on the same papyrus, or combined in the very same spell; scholars usually specialized in one or the other, and for a long time, Greek was more prestigious as both an ancient language and a scholarly focus. Translations of the written spells also tended to be studied in isolation from material evidence, such as amulets, clay figurines, and birth tusks. Fortunately, in the last twenty-five years, the study of ancient magic has taken a more holistic view. There’s certainly no shame in doing what young Battiscombe Gunn did and trying to walk a mile (well, a few cubits) in the sandals of an ancient priest.

Samuel MacGregor Mathers performs an Isis ritual for the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, which he helped found.

Still, modern practitioners who actively worship the Egyptian gods remain apart from Egyptology, even if they draw on academic literature in building their image of the ancient past. Kemetic temples (from Kemet, an ancient name for Egypt), found predominantly in the United States, base their worship on some sound research. However, there are many ‘alternative’ interpretations of ancient Egypt that do the opposite, twisting the evidence for magical practice and other forms of priestly knowledge. Pseudo-scientific theories about astrology, aliens, and the ‘true’ age of the sphinx and the pyramids have been around for decades (writers Robert Bauval and Graham Hancock have sold millions of books in this vein), and they flourish on the internet. These interpretations inspire sighs of deep frustration in Egyptologists and others who feel passionately about the ancient past, not least because many of the proposals – that only extraterrestrial beings could have built the pyramids, for instance – are rooted in the frankly racist idea that ancient Egyptians were not intelligent enough to have quarried blocks of stone and stacked them up in a solid geometric form.

Today, Egyptian Magic™ comes in a convenient plastic tub – if, that is, you’re in the market for an all-purpose skin cream made with olive oil, bee products, and ‘divine love’, as the ingredients list used to read. Divine love has disappeared from the cream’s labels of late. The official bodies that regulate ingredient labelling tend to be sticklers for demonstrable facts, and love of any kind is difficult to measure, much less replicate, in laboratory conditions. However, a dose of divine love fits very well into the ancient aims and marketing claims of the Egyptian Magic™ brand, which brags a formula handed down from ‘the great sages, mystics, magicians, and healers’ and claims to offer the skin-rejuvenating properties you would expect with such a pedigree. The company’s founder, Westley Howard, changed his legal name to LordPharaoh ImHotepAmonRa after a mysterious stranger named Dr Imas revealed the secret formula to him, which is said to be based on an ancient Egyptian recipe. Cue twenty-five years of commercial success, from high street shops to Harrods.

Think what you will of this business’s backstory, but there is one thing about it that’s as old as the pyramids: Egypt’s reputation for magic. In the Book of Exodus, Moses and his brother Aaron confronted the pharaoh’s magicians in a battle of miracles, while the astonishing skills of Egypt’s priest-magicians were so renowned among the Greeks and Romans, that a white-robed, shaven-headed sorcerer became a fixture in literature and art. Magicians were the heroes of Egyptian tales as well, and Egyptian magic was even credited, after the fact, with the birth of Alexander the Great, whose real father was said to have been an Egyptian pharaoh with magical skills. The ultimate master of magic was the fictional Hermes Trismegistos, admired from Al-Andalus (Islamic Spain) to Renaissance Italy and beyond thanks to his knowledge of ancient wisdom, alchemical promise, and pan-religious appeal.

The kinds of magic and wisdom attributed to these Egyptian wizards didn’t involve pulling rabbits out of hats or sawing a shapely assistant in two, although we know that the Old Kingdom magician Djedi could successfully re-attach an animal’s head to its body. Most of the superpowers at an ancient magician’s command were shaped by far more practical concerns, because a little help from on high went a long way when life went awry. That unseen forces were at work in the world, for good or ill, seemed an obvious conclusion to people when they observed natural phenomena like floods, storms, and shooting stars, or everyday experiences like fevers, dreams, and childbirth. Before there were microscopes, periodic tables, or laws about product labelling, the best way to understand and, if at all possible, influence these unpredictable events was to seek divine intervention via magic – however much it may seem, from a distance, like some kind of superstitious skulduggery.

The imposition of a strict division between science and superstition is a very recent phenomenon. It’s an example of the kinds of divisions that occur in a society when things that have been pretty indistinguishable start to rub each other the wrong way. It is in fact very difficult to draw a distinction between ‘religion’ and ‘magic’. Without trying to sort remnants of ancient magical practice into one or the other of these categories, we can start to appreciate it from something that gets us closer to an ancient Egyptian point of view. We’ve encountered some strange things: disease-causing demons, the cheerful use of crocodile dung, and invisibility spells that probably haven’t worked, for those of you who dared to try them (sorry about that). Although there is much, too, that is familiar: labour pains, unrequited passion, or a bad night’s sleep.

It would be over-simplifying things to say that the people of ancient Egypt were ‘just like us’. Individuals are formed by the society they live in, and every society has its unique ways of being, doing, and thinking. Studying Egyptian magic cannot transport us back in time, turn us into a bird, or make us invisible. But it can give us important insights into the hopes and fears of the people who lived in the time and place we know as ancient Egypt, and add depth to our picture of Egyptian society, whose long lists of kings and rows of similar-looking statues can sometimes seem inscrutable. Inscrutability was part of the point. Scratch the surface, though, and all those sorcerer-princes, proud wizards, and wise women were as vulnerable as any one of us. No doubt they did their level best to help their even more vulnerable clients and colleagues – and faced with fate, who wouldn’t wish for a talisman to hold tight to, especially if it came with a dash of Egyptian magic’s divine love.

May all your enchantments be enchanting. Very effective. Proven a million times!