GETTING TO KNOW THE MARKETPLACE FOR YOUR WORK

You’ve seen fabulous products at your favorite shop and asked yourself, “How the heck do I get that gig?” Maybe you’ve wondered what’s involved in having your work licensed on Blue Q’s funky tote bags or an insanely cute Chronicle Books journal.

In this chapter, I’m going to tell you specifically which markets buy the most art and what they look for. I’m going to tell you how to find this work, what licensing is, all about trade shows, and why personal work is your secret weapon. I’ll show you a number of the art and craft markets that we love, focusing on categories that buy huge quantities of art every year.

Each market has its own set of criteria. The wall decor market loves paint and texture, for example, and the quilting fabric market loves decorative repeat patterns.

I’ll show you products that my artists have done, and tell you why they got the license.

Now we’re getting to the good stuff! (Maybe it’s even why you bought this book). I know you love making things, I know you’re creative, but what if you need to pay the rent? I’ll show you some ways to turn your passion into a lucrative profession.

To really give you the inside scoop, I’ve interviewed some of my favorite art directors, asking questions I thought you would ask if you had the chance—and they’ve generously shared their insights. Then, to sum up a great deal of what we’ve been talking about, I’ll show you how I turned one of my passions into an international craft product line.

Do you love to sew? Do you love to hoard fabric? Would you rather go to a fabric store than out to dinner? (I would!) Then bolt fabric may be an area for you to pursue. Bolt fabric is the term for fabric-store fabric, as opposed to fabric used for retail apparel. The burgeoning craft market has really made the bolt fabric market cooler and hipper, and this is a super-exciting area. The quilt market is huge too; those quilters love their fabric!

What is key for a great piece of art for a fabric line? Repeat patterns are important. You ask, “Do I have to do the repeats myself? I don’t know how to do it!” No, you don’t have to do the repeats yourself. That’s the fabric company’s job. You do, however, usually want to show some sort of repeating elements to give a flavor of how your work would look in repeat.

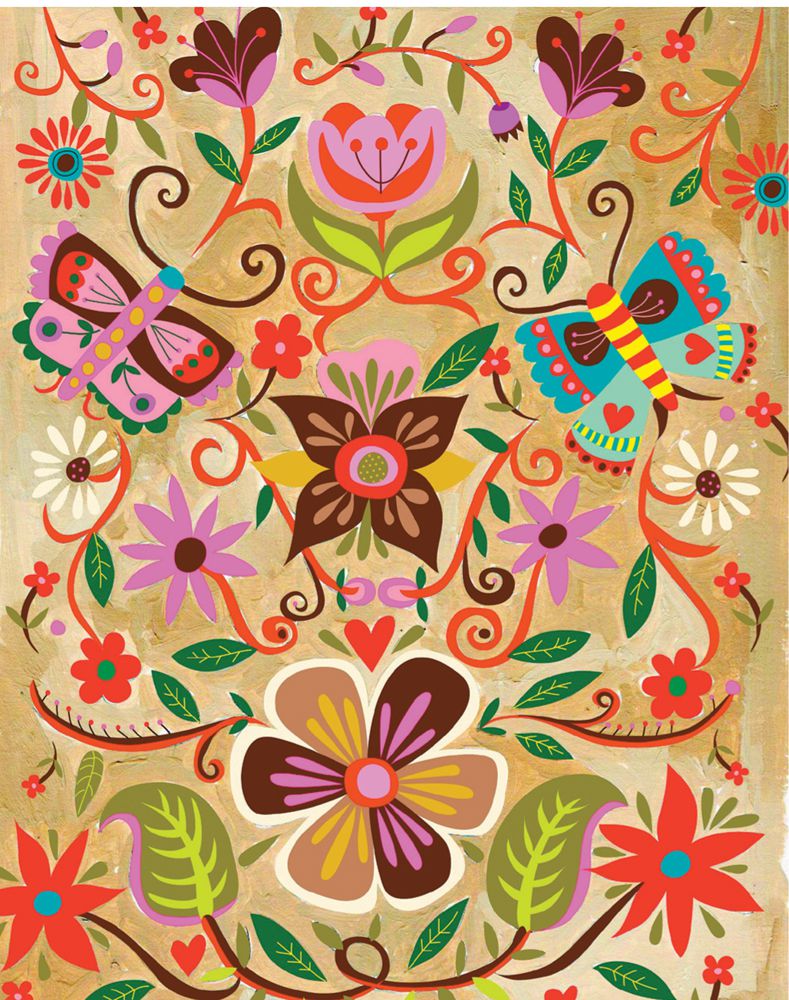

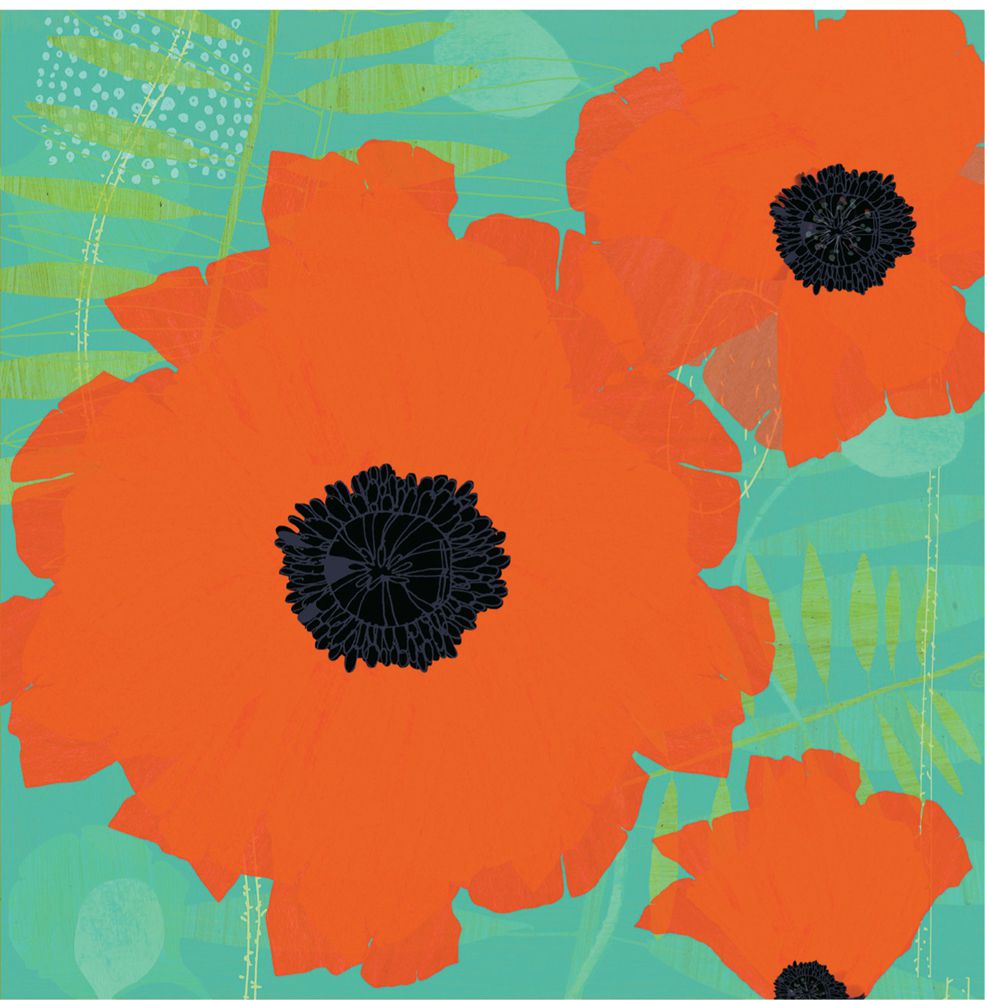

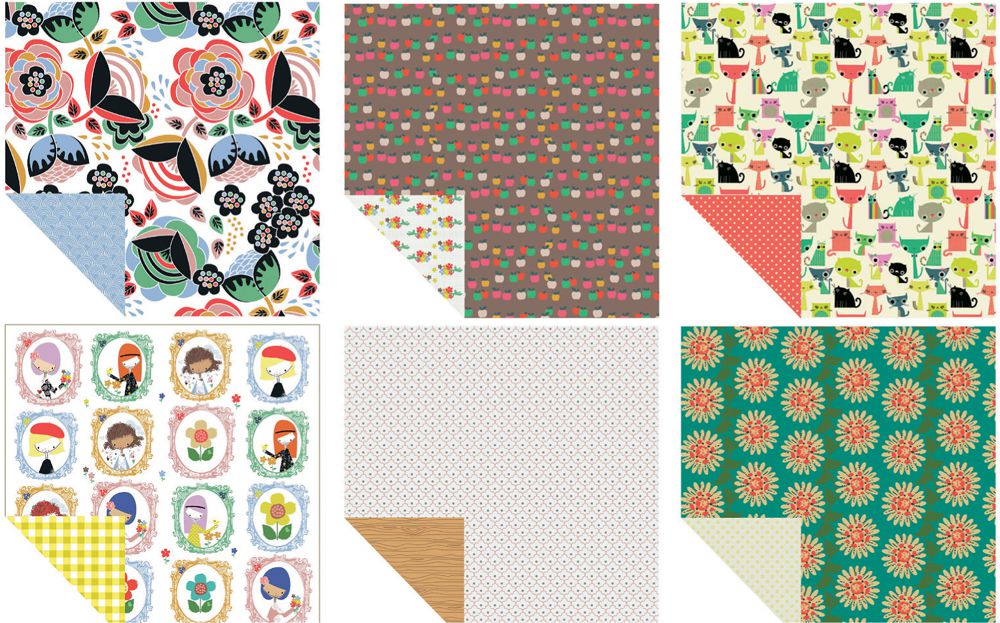

This piece by Helen Dardik is chock-full of great bits that a fabric company could work from to create a collection of fabrics.

Adobe Illustrator and Photoshop are great to work in for this category because fabric needs to be printed with each color separated. Working in layers is great. It gives the client more flexibility.

Imagery varies. Floral is always, always, always big. But there’s lots of room for variety. Ask yourself if your design would be fun to sew with. Could you make a quilt with it? Clothing? An apron? You can stay in tune with the trends by looking at all the wonderful fabric online on sites such as www.TrueUp.net.

Fabric companies like to see a variety of artwork that would work in a whole fabric collection. Then they will license the art for an exclusive fabric collection. Typically, you are expected to be exclusive with one fabric company. You are generally paid on a royalty basis by fabric that is sold. Real money is to be made by having a relationship with your fabric company and having several collections with them.

How to find this work: Attend the International Quilt Market or Surtex, or peruse the Web or your favorite fabric stores to compile a list of fabric companies that you love. Then, check their websites for submission policies.

Jillian Phillips’s piece would be great for any number of markets: baby apparel, a stationery collection, a fabric line, kids’ bedding, or scrapbooking papers. It’s considered a repeat pattern even though it’s not exactly a precise repeat. That’s okay. Most companies have in-house textile experts who take care of that for you. Notice how desirable this would be for a client to buy. It’s got the repeat pattern on top, and then a lovely banner format at the bottom, known as a coordinate. This provides ample opportunity for the art director to create. For example, the top portion of this piece might be used for a journal cover, and the bottom banner could be a header on the inside pages. Then, possibly, one of the owls could be made out of resin and dangling from a ribbon placeholder. You get the picture.

Julie Freimuth is the visionary art director at P&B Textiles. They’re one of the top quilting fabric companies, and they license lots of really exciting work.

How often do you license or commission with a new artist?

At P&B, we commission in the area of six to eight per year, some years less, some more.

How do you find artists? Do you ever look at sites such as Etsy, Pinterest, print & pattern, and so on?

We find artists everywhere and anywhere! Definitely through Etsy, the print & pattern blog, Pinterest, and others, including Spoonflower (digital printing resource and community), and through other blogs. We debuted a collection in January called VeloCity, which is based on the artwork of Jessica Hogarth, who I first saw on www.printpattern.blogspot.com

We also license artwork through wall art licensing companies, the likes of World Art Group, Art In Motion, etc. Artists approach us as well, and we have an open-door policy with regard to submissions, though generally it’s less often that we adopt artwork through that channel.

Do you attend trade shows to find art?

Yes! Surtex and Printsource are the main ones on my radar screen. Though in the past, I’ve also scouted many a wonderful print at Indigo (Première Vision, Paris) and at Heimtextil (Frankfurt)—amazing array of artwork at both of those.

Surtex is maybe my favorite of the domestic shows because there is artwork for purchase there, as well as for license. And the stationery show and the home show usually run concurrently, so I can cover a lot of ground in surface design at that show.

How long does it take you to respond?

It can take me a while to initiate or formally respond to an artist. But that does not mean lack of interest.

How do you feel about an artist following up after sending you work?

I think it’s fine (email is good)—as long as the artist is okay with hearing a response that a decision hasn’t been made! Again, that doesn’t equate to lack of interest.

Does an artist have to submit work in repeat? What do you prefer?

Definitely not! It can be limiting to their creative process. We’re a textile house . . . we are good at repeats—we do them day and night—so we don’t want that from the artist. We want the raw material as a starting point.

Some clients love layered digital files, such as Photoshop or Illustrator files; some prefer traditional media, such as paint; others can’t use painted images due to technical limitations. What do you prefer?

Paint or other traditional media is fine for us. We prefer to work with art that was originally created in some form of traditional media, rather than artwork created totally digitally.

Any pointers on what makes a great working relationship?

I would say having access to a significant amount of artwork to work with is important. Equally important is working with artists who have a flexible attitude in working with us in translating the artwork for textiles. A lot of time and energy goes into developing a collection, and we definitely want it to be a pleasurable experience, and successful outcome, for all involved.

What’s your best advice for an artist to get work in your field?

Try to understand that developing a collection of textiles is a very different process than licensing a single design directly onto a product. There is a whole creative process that is just beginning upon receiving the original artwork. Expect the art to modify in some way, in a collaborative process, and expect it to take a significant amount of time from start to finished fabric.

I would also say to show work that shows an understanding of allover surface pattern, and show a range of work that can be used together. Not all the work needs to be this way, but it does help us as textile designers to see the artwork relating more readily to our product. Also, being willing to partner with us to create artwork pieces to round out the textile collection is a big help.

From a fabric collection for P&B Textiles, by Carolyn Gavin

Evie Ashworth is the trendsetting fabrics design director at Robert Kaufman Company, one of the most highly respected names in quilting fabric.

How do you find artists?

There are multiple avenues: Etsy; print & pattern; agencies; shopping products; direct submissions; scrapbooking and stationery companies; art and trade shows; and quilt market connections.

Do you attend trade shows (besides Surtex) to find art? If so, which ones?

Printsource, Craft & Hobby Association, Los Angeles International Textile Show, Magic, Licensing Expo, Quilt Market.

Is there certain subject matter that’s always hot?

Novelty designs are a basic need, and lifestyle-type designs such as cooking, gardening/florals, and sports.

Are you saturated with a certain motif or concept?

Computerized flat florals with all the same coordinates.

Part of a fabric collection for Robert Kaufman Co., by Suzy Ultman. Look at how alluring the art is even just seeing a small strip of each design. This is important to fabric companies because the art will be seen on bolts that are stacked.

Photo by Suzy Ultman.

Everybody is familiar with children’s books; that’s why it’s one of the areas people think of first when they think of breaking into the art market. And it’s a good area. Traditional book publishing was hit hard by the recession. Don’t worry about that; just work harder on your art and make it irresistible! People continue to make babies, so there will always be a need for children’s books. And the advent of interactive books should open up some interesting possibilities.

Artists love picture books because they are a wonderful opportunity to have a long-term creative project that allows you to dig in and create your own magical world.

I am often asked, “Do I need to write the book myself?” No! In fact, it’s very rare to be amazing at both art and writing. Art directors have manuscripts that they need illustrators for. They make it their business to know the best artists out there and are always on the lookout for new, fresh top talent.

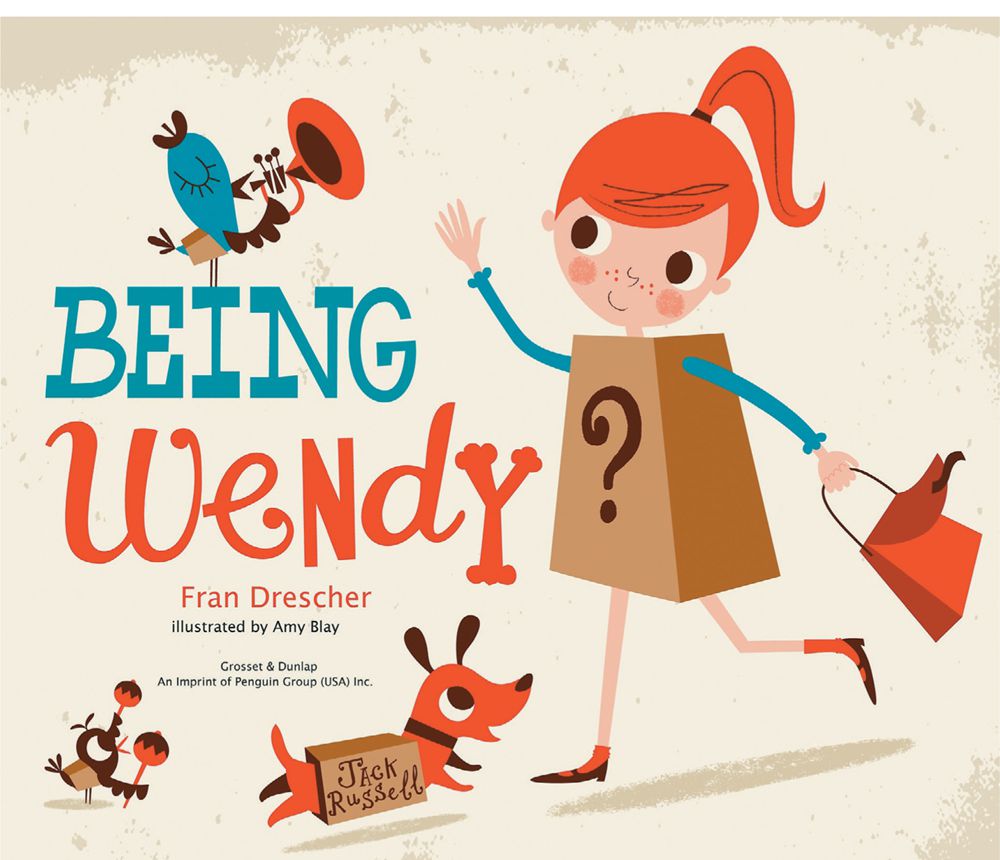

Amy Blay fully illustrated this children’s book, which was written by Fran Drescher, of the TV show The Nanny. Why was she chosen to do this book, and why is this cover great? Appealing characters, stunning design, great style.

This cover by Helen Dardik has great lettering and characters. A variety of emotions are illustrated, too.

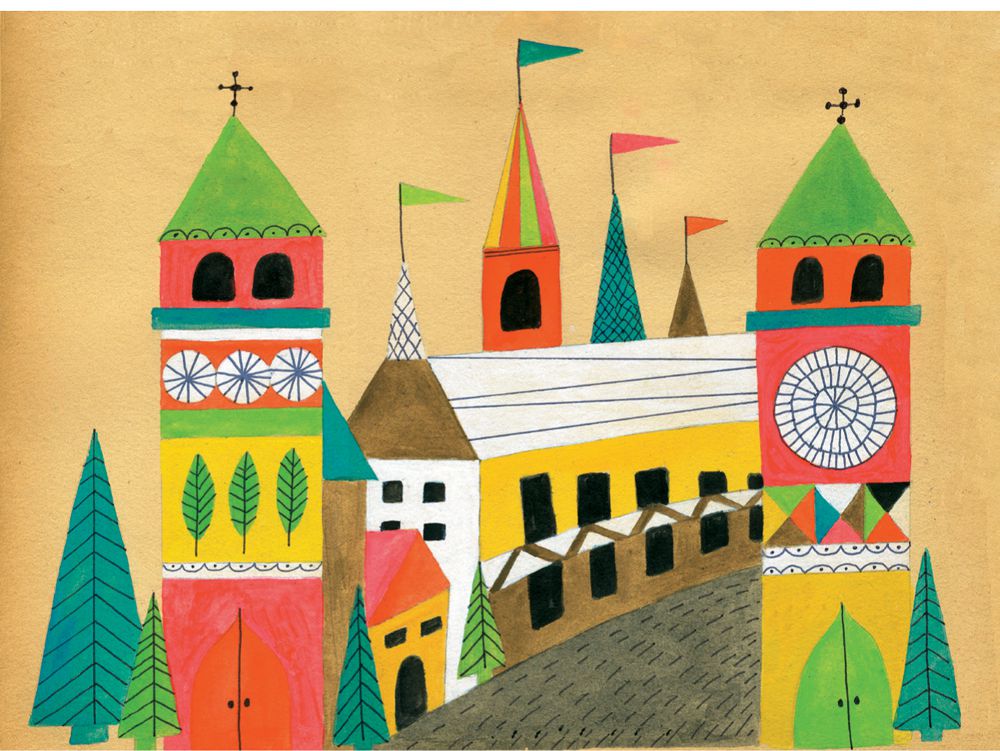

This is a piece that might lure a children’s book editor to commission the artist to illustrate a children’s book. The artist, Hsinping Pan, creates otherworldly, magical environments.

As you can see from these examples, picture books are character-driven, whether the character is a child or an animal. To prove to an art director that you can handle illustrating a kid’s book, draw some really cute/cool/sassy characters in a variety of poses. First, art directors love to see expressiveness in the characters. Can you show your character laughing, sad, sassy, thoughtful, happy?

Second, you’ll want to put your characters in scenes or environments. Where is the story taking place? Can you create a world that is really engaging? Being able to do hand lettering is a big plus, too.

To land these types of jobs, you don’t necessarily have to present a fully illustrated book. Art directors have told me that they suggest artists illustrate three or four spreads of a well-known fairy tale in their own way. Show your stuff and wow them with your vision!

The beauty of this market is that there are a huge range of styles that are appropriate. You can work digitally or traditionally. There’s great room for unique looks, too.

How to find this work: Go to your local library or bookstore and find the companies that are publishing the books you love. Check their websites for submission policies.

Mike Lowery is an illustrator and professor at the Savannah College of Art and Design in Atlanta, Georgia. He emailed us a portfolio of personal work several years ago. We were blown away by what we saw. His work was charming, and had a great deal of wit that we knew kids would respond to. More accurately, we were pretty sure that children’s book editors and art directors would respond. To top it off, his lettering was appealing and the printmaking-style texture and line quality were just wonderful. It was his own unique style.

This mummy piece was a personal piece that Mike created for himself, and it got him a lot of work. Here’s why: It’s an adorable character with an intelligent-boy style. For children’s books, art directors are looking for a delightful character. Children’s books are character-driven, so a great character is absolutely a must. Wit and lettering are a plus.

In addition to receiving never-ending requests to illustrate children’s books, he’s also gotten commissions for stationery, puzzles, kids’ clocks, animated online greeting cards, children’s T-shirts, and many, many picture books.

Mike does what he loves, and it comes through in his work with intelligence, wit, and an edgy sweetness. His personal work showed what he was capable of, and it attracted work.

Just as in picture books, there’s always a ready market for baby apparel because babies keep being born in any economic time, good or bad. This is a fun area because there’s room for a lot of creativity, but it, like all apparel, is very trend-driven. Many of the art buyers buy based on trend reports, which generally come out of Europe and predict the trends 1 1/2 to 2 years in advance. This makes it a bit harder to break into because you can’t just do any imagery you like. It can be very specific. For example, a recent baby apparel trend showed lovely pale, muted, silhouetted dandelion puffs. Certain looks are in; certain looks are out. Perennial imagery includes baby animals, flowers, and butterflies. They’re benign and happy. Colors can be joyful or soft.

You see here that the art shows a placement graphic, which is the motif. There is also the repeat pattern, and sometimes the repeat pattern is placed in a template. Art is sold at print shows, such as Printsource New York or Indigo, and the art buyer usually buys the print outright for a flat fee.

Selling prints is great because you make what you want, freely and without art direction, and then sell what you’ve got, as opposed to commissioned work.

How to learn more: An excellent online class is Rachael Taylor’s print and pattern course. Also, frequent printpattern.blogspot.com to see the most wonderful collection of prints.

How to find this work: Show at Surtex, Printsource, or Première Vision New York. Europe, where the market originated, also has many wonderful print shows.

Art by Jillian Phillips. The photo collage combined with illustration is an up-and-coming trend.

Art by Allison Cole. This is the classic presentation of a print for a show like Printsource. There is a placement graphic on top, a repeat pattern below, and the color blocks on the bottom.

Art by Jillian Phillips. Line art and blobby shapes are a nice look.

Art by Jillian Phillips. Children and baby apparel themes frequently include baby animals, flowers, and cute insects such as butterflies. Note that the colors are becoming more and more sophisticated for baby. It’s not your mother’s layette.

Silvia Dekker’s art is used on baby clothing for Hema.

Photo by Silvia Dekker.

What is the home decor market? Think Bloomingdale’s, ModCloth, Anthropologie, Pottery Barn, IKEA, and Crate & Barrel. Categories that especially have a need for repeat patterns include bedding, kitchen linens, aprons, and place mats. Nonrepeat imagery is great for tableware (plates, cups, platters) and holiday ornaments, for example.

Artists are excited about print and pattern these days, and it’s really taking off as one of the hottest areas in home decor, attracting some of the very best artists.

Techniques may be digital or traditional media. Fabric items usually require a limited number of colors (typically between five and eight) due to the nature of fabric printing presses.

How to learn more: As in baby and children’s apparel, Rachael Taylor’s print and pattern e-course is well worth checking out, as is www.printpattern.blogspot.com.

How to find this work: Show your work at Surtex, Printsource, or Première Vision New York. Some artists swear by the AmericasMart (“Atlanta Gift Mart”), for either walking the show or exhibiting.

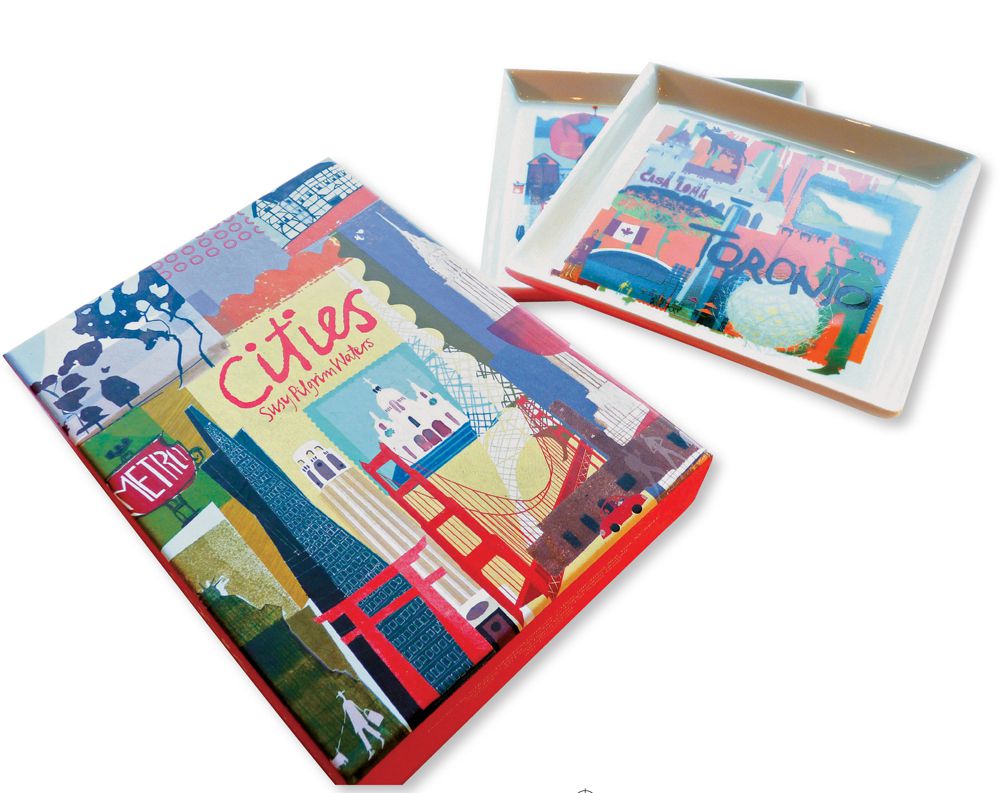

Susy Pilgrim Waters’s gorgeous art looks great on kitchen products for Crate & Barrel: ceramic ware, linens, and paper napkins.

Photo by Susy Pilgrim Waters.

Bedding by Sarajo Frieden for Land of Nod.

Photo by Land of Nod.

Licensing is the term used to describe when you sell the right to a company to use your art. Licensing is fantastic because you have the opportunity to sell your art to multiple companies in different categories and leverage income on the art. For example, Silvia Portella’s art was licensed to two different manufacturers of the two products shown, right: the zipper bag and the journal. The licensing agreement for the zipper bag might read something like this:

Use: The right to use art (file name here) on zipper bags

Duration: For the life of product

Territory: Worldwide

Exclusivity: Exclusive for zipper bags for the life of the product, worldwide

Royalty: 5%

Advance: $500

An array of products on which we’ve licensed our artists’ artwork: paper napkins, magnets, zippered bags, ornaments, cloth dish towels, journals, embroidery kits, and more.

Art by Silvia Portella for Blue Q and journal for LaMarelle.

There are two areas to cover: rights, which means which products the company has the right to use the art on, and exclusivity, which means which products no other company can use this same image on. Be sure to address the duration (period of time) and the territory. Generally, the manufacturer rightly expects that you’ll not sell the art to a competitor in the same category or product. In terms of time frame, I like the phrase “life of product” because that means the company has the right to use your art as long as they keep selling the product. When they are done selling, the rights generally revert back to you.

Advance means a fee that is paid to you at the start. It’s usually an advance against royalties, which means that you’ll begin to earn royalties once that fee is deducted. Not every company gives advances.

Sometimes you’ll get a royalty, and sometimes you’ll get a flat fee. Both have their advantages and disadvantages. Sometimes a flat fee (which is a one-time fee) is better because you’re given a set amount of money up front, and it can be better than what you may stand to make in royalties. Sometimes royalties don’t pan out. How do you choose? Because you don’t have a crystal ball, you might ask the client what he or she thinks will be more lucrative for you. Very often, clients are candid. The art director is generally objective and will tell you, based on past experience, what is better. If, for example, you license your art for a one-time fee and your product does well, then you have a basis for negotiating for a royalty next time. Until you have a track record in the category, or with that client, it’s hard to know. But don’t worry; it’s not fatal. Over time, you’ll build relationships with companies and it’ll be lucrative for all parties.

Susy Pilgrim Waters’s travel art series was licensed on note cards (boxed set, “Cities”), and on travel plates for Crate & Barrel.

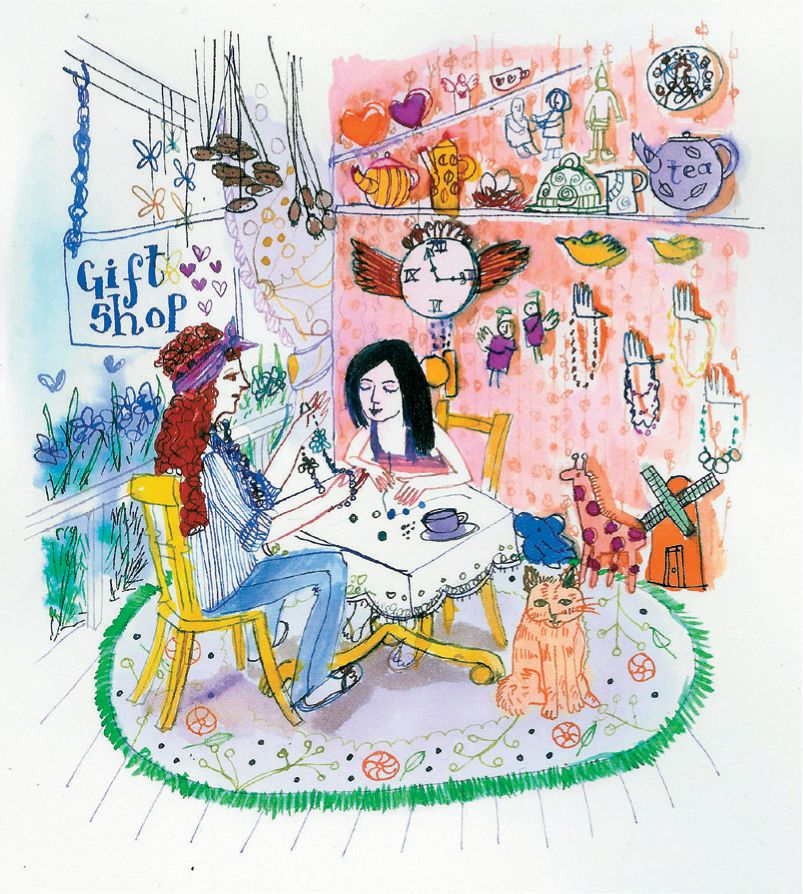

The gift market includes anything you might see at your favorite little boutique that is not apparel. This huge area includes any fun or beautiful thing you might purchase as a gift. Some of the gift product categories that buy a lot of art include tote bags, phone and iPad covers, laptop skins, pencil cases, mouse pads, notepads, toys, games, and magnets. This is a superfun market, and the sky’s the limit. The main thing is to delight and have a fresh look. You can work in any style, any media, and any trend.

How to find this work: Find the names of companies by visiting your favorite shops. Attend the New York International Gift Fair or troll its site to find clients and get a feel for what’s what. Note that the smaller companies usually do their own design and may be less open to buying art. Still, lots of companies are worth contacting.

Attend or exhibit at AmericasMart show, Surtex, or the Licensing Expo. We’ll dig deeper into trade shows later in this chapter.

Art by Silvia Dekker for Hema.

Photo by Silvia Dekker.

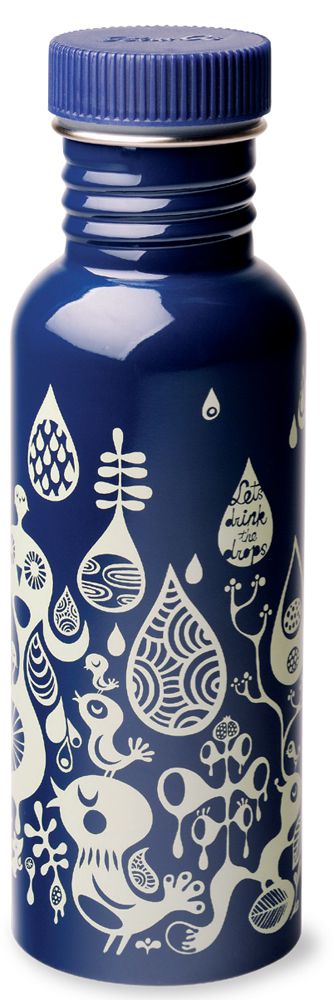

If you want to license your work with probably the grooviest giftware company in the country, art director Mitch Nash is your man at Blue Q. When we take on a new artist who is too far ahead for most clients, Mitch is the first person we’ll show their work to. A small company in western Massachusetts, Blue Q is known for its incredible tote bags, water bottles, and Dirty Girl Soap.

How often do you license or commission with a new artist?

Constantly. We have products in development with fifteen or twenty artists at times, and we need enough of them to be new to keep the line fresh. It takes a lot of work to get to know someone new, though. But it’s one of the best parts of the job. We love the whole courtship thing.

How do you find your artists?

Our schedule is biannual; we make sixty-five or seventy items twice a year. Researching artists sometimes takes a backseat. We sell such a strange collection of categories—chewing gum, recycled bags, paper lanterns, weird breath sprays, soap, lip balm, cigar boxes. Each research resource is different depending on what we are trying to build. Illustration is the easiest to research, because there is so much good stuff out there.

If an artist wanted to really blow your mind with a great presentation to land work with you, what would you suggest?

Send some sushi; you’ll definitely hear back! Actually, we look at every postcard that shows up, and they’re the perfect introduction, basic as they are. We try to respond to every one we get, and we look at the websites.

Art by Helen Dardik for Blue Q.

Photo by Blue Q.

Art by Helen Dardik for Blue Q.

Photo by Blue Q.

Do you like to see mock-ups or prototypes of product ideas?

Only if we have made arrangements in advance.

How can working for Blue Q be lucrative for an artist?

Repeat business. We love doing multiple projects with people; it’s efficient for us. We already know the person and their quirks and style of working. Our best-paid artists aren’t the ones making one-offs; they’re making groups of stuff, hopefully season after season. We also pay a few points of net sales, so the quarterly statements add up.

Is there certain subject matter that’s always hot? Are you saturated with any motif or concept?

“When in doubt, put a bird on it.” We’re guilty of doing our share of bird and flower motifs here. But we happen to like them and push them well beyond the average. We also like themes that represent female empowerment, and anything character-driven we have a fondness for, because then there can be some action and a little narrative, which makes a conversation piece.

What’s always hot for Blue Q is humor. Everyone thinks we have good comic timing, and we’ll be a bit risqué. So anything dealing with sex, or being a bitch, or a bird that is a bitch! Then there is gorgeous surface design that we apply to all of our different shapes of recycled bags. Illustration is on a roll. Everyone’s really digging fresh, random illustration from around the world.

Photo by Blue Q.

Art by Silvia Portella for Blue Q.

What’s your best advice for an artist to get work in your field?

Remember that you’re in the surprise business. I know we are at Blue Q—surprising the audience is our bread and butter. Otherwise, there is no point, and we may as well make stuff for airport gift shops. But being surprising means deep drilling through layers of predictable goo, and it gets hard before it becomes easy. But there is a profit in the surprise at the end.

Whose work or wisdom has inspired you?

I once heard Maira Kalman say her work was a blend of surprise, humor, elegance, and humanity. That was succinct. When my parents took me and my brother to see Alexander Calder’s Circus at the Whitney when I was a kid, that was a game changer. It was very surprising. Michael Mabry was the first so-called design rock star I ever got to work with, and he told me art direction is gut instinct.

Is there anybody who has not received a greeting card? It’s a huge market with a never-ending need for art. Fairly easy to break into, it can be lucrative over time if you develop relationships with the companies and sell or license a great deal of art to them.

Think big names like Hallmark, Papyrus, and American Greetings, as well as some of my favorite boutique card companies—Madison Park Greetings, Galison, teNeues, and of course, the much-loved design- and art-driven Chronicle Books. (Unfortunately, those charming letterpress companies you love tend to do the art themselves.)

What do you need to show the art director? You can present a variety of styles, but each piece needs to be arresting, gorgeous, and able to stand alone. Think of how the card will look on the rack. Also think of how the card will look in the sales catalog, reduced in size. Does it read really well? Is it graphically strong?

Companies may either license or buy your existing pieces, or they might commission work from you based on what you show.

The top categories include winter holiday/Christmas cards and birthday cards.

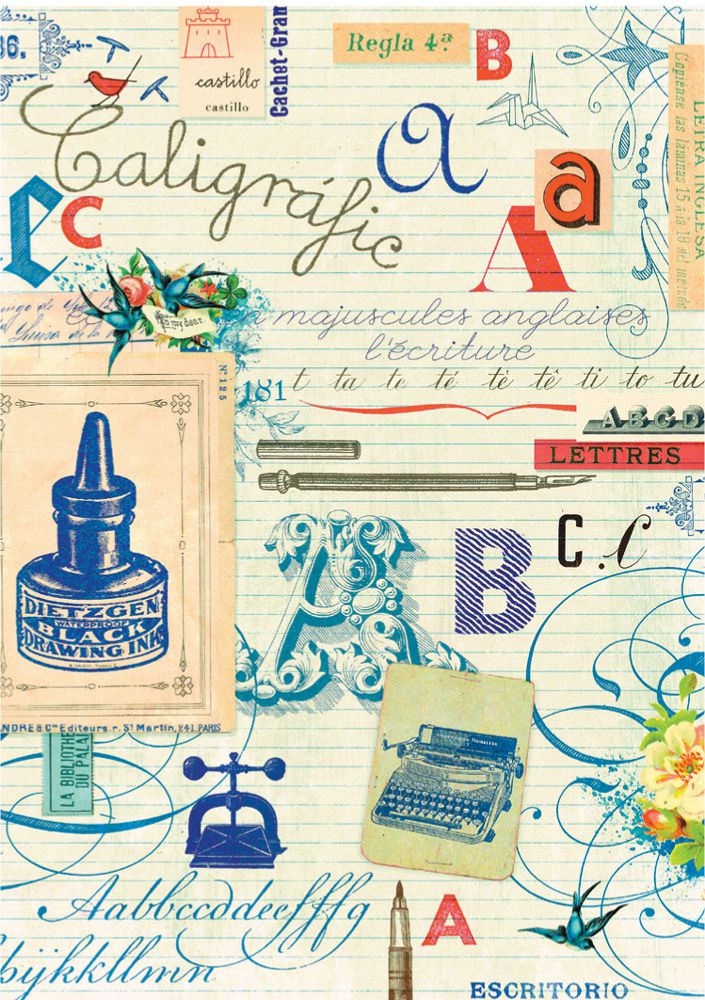

Other paper categories that need art include note cards, address books, and stationery. Journals are huge, and they always need some arresting visuals.

How to find this work: Walk the New York International Gift Fair, or walk or exhibit at Surtex. Go to your favorite shop and find cards you love. See who’s manufacturing them and email samples of your work to them.

Photos by Alison Cole.

Allison Cole’s charming art was licensed throughout this book for Pink Ghost.

Art by Carolyn Gavin for Ecojot. These pieces are great for the paper goods market as they could be used on journal covers, greeting cards, notepads, and stationery products. Carolyn’s distinctive brand is easy for us to license. It’s gorgeous, and she’s a great colorist and an original.

Photo by Carolyn Gavin.

Photo by Carolyn Gavin.

Journals by Carolyn Gavin for Ecojot.

Card by Helen Dardik for Marian Heath, Inc.

Suzy Ultman arrived in my studio about five years ago as a student in a portfolio review class I was teaching. She was a graphic designer who had just moved to Boston from Portland, Oregon. Through the course, she got in touch with her fabulous creative self and blossomed as a person and an artist.

Suzy’s work has such joy. It’s such a fresh look. She lived in Amsterdam for a while and was one of the first to do a midcentury Dutch style. Beyond that, her color sense is gorgeous and brilliant. Every single shape is designed with care. It’s playful and sweet without being insipid.

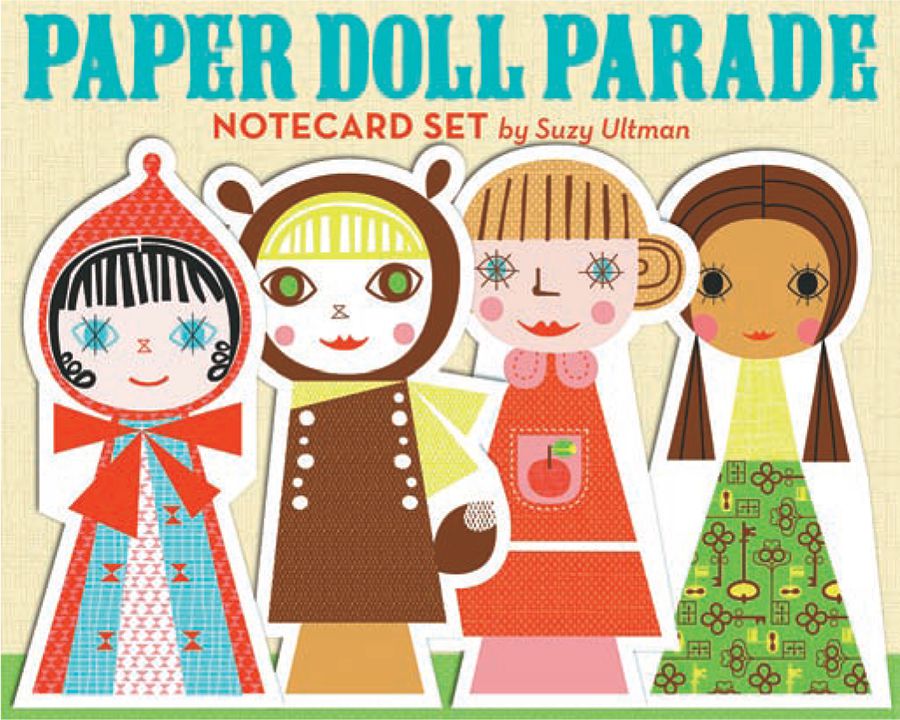

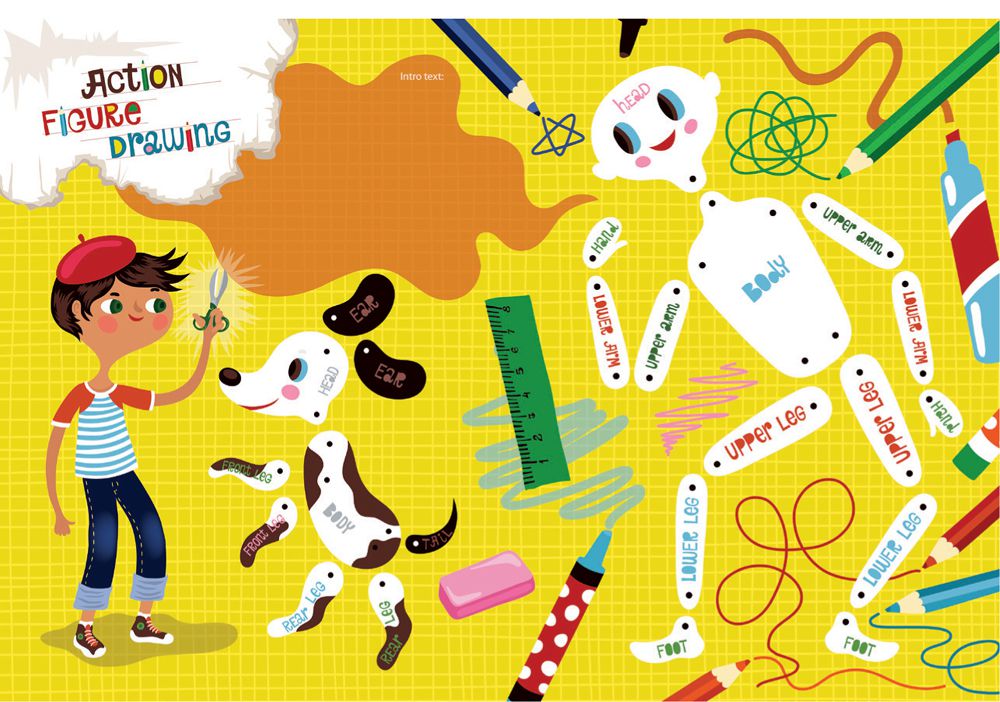

Strong icons and stand-alone characters like Suzy’s lend themselves to a lot of different projects, like these very updated paper dolls. They’re such a strong graphic read. The manufacturer knows that a product has to pop on the shelves in the store, so it can’t be too soft and pale. With people buying on their smartphones and iPads and computers, it has to pop on a screen, too.

Suzy is making ridiculously gorgeous art—and it’s lucrative for her because manufacturers need great art to sell their products, and great art is what she makes.

Photo by Suzy Ultman.

These are projects Suzy got as a result of showing her personal work. All three where for Chronicle Books, a leader in stylish paper products. Projects are as follows, in order of appearance: Die cut stationary set, felt-applique journal, and a notecard set.

Cynthia Matthews is the art director at Mudpuppy, Galison’s kids’ division. Galison has always been at the forefront of great art and design in the paper goods and gift markets.

How often do you license or commission with a new artist?

We commission art every couple of months—generally in spurts as we green-light a new series of projects. We are always looking for new artists, so the look of the line is always evolving.

Do you like to see mock-ups or prototypes of product ideas?

No, this doesn’t help us. Our art needs are very specific, and we choose specific themes each season.

Is there certain subject matter that’s always hot? Are you saturated with a certain motif or concept?

Pirates, robots, and princesses have been hot for us for a while now. We are affected by adult trends as well, such as the popularity of owls, but to a lesser degree.

Any pointers on what makes a great working relationship?

The key to a long-term relationship for us is simply that the illustrator is open to suggestions and easy to work with. Sending work on time and answering emails in a timely manner go a long way. There are several artists who are very talented but are so difficult to work with that I’d think twice before hiring them again.

We hire artists for their style, but we also need to create work that will sell to our customers. Sometimes that means compromise. When an artist is inflexible, it limits the relationship. For example, if the artist tells us she will “only do brown eyes,” it limits my ability to appeal to kids across a wider platform.

I’m also looking for versatility and to see how far an artist can stretch. Can I commission a technically difficult project and know it will be done well? Can they handle a wide range of subject matter? Can they do an attractive female and a grisly pirate? Is their color palette flexible, or do they always use the same palette in each piece? The more versatility I see, the more themes and types of projects I can consider them for.

We like to see the artist bring his or her imagination to the project. We send rather general illustration briefs in order to leave room for the artist to have fun with the project. Because we deal with a lot of the same themes multiple times, this helps keep the images fresh and unique. Often the artists surprise us with the details they come up with.

What’s your best advice for an artist to get work in your field?

Style is very important to us. Many of the artists we see have styles that are too mass-market for our customers. Also, we like to see new images so we know where the artist is moving artistically. I also like when artists stay in touch. If we’ve done work together, let me know you’re interested in new projects.

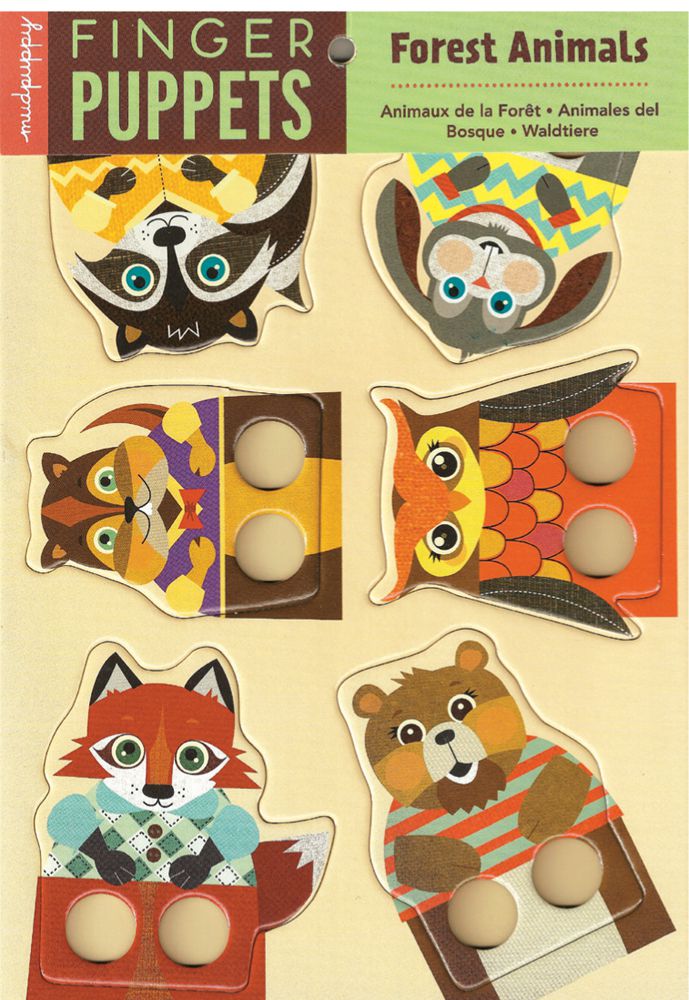

Jenn Ski’s animals made great finger puppets for Mudpuppy, a division of Galison.

Fiona Richards is both the owner of Cartolina Cards and an artist represented by Lilla Rogers Studio. She does all the art for her stationery company, which uses vintage ephemera and sells to boutiques around the world, including Anthropologie and Harrods.

You do everything from design to manufacturing. Why did you decide to run your own card company, as opposed to just licensing your art?

I wanted to have a product. Greeting cards were a great way for me to apply my art directly onto a product, keep the original art, and then apply it to other products in the future.

What skills does one need to be able to successfully run his or her own company? What type of person does best?

Well, you have to be brave; it’s not for the fainthearted. And, it’s definitely not a get-rich-quick scheme.

To be successful, you have to have a unique product that people are drawn to—which requires a lifetime of observation and a hopper full of skill sets that are uniquely yours. If you can produce a unique product that people want, if you can stay focused and committed, then you might be exactly the right kind of person who can run his or her own company.

Why did you get an agent?

I’ve always believed in paying a professional to sell my art/work for me. We have wonderful distributors and sales staff at Cartolina. I’ve paid galleries to sell my paintings in the past. I’m busy making art; my agent is busy selling it for me.

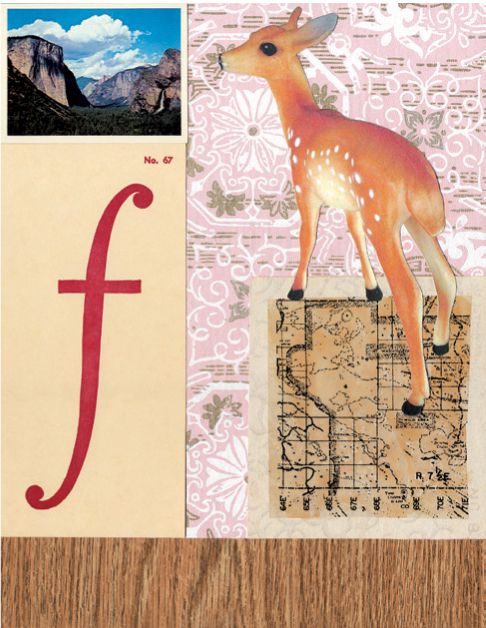

Fiona Richards’s cards and journals for her company, Cartolina.

What’s the best part of your career? What’s the toughest part?

We live in a fairly remote area of British Columbia, and I absolutely love the idea that I can produce art and cards in my studio in the forest; meanwhile, shoppers are walking down Kensington High Street in London with Cartolina cards in their shopping bags.

I’m a business junky. I love seeing business happen. I’m also a control freak. I work very long hours and usually work six days a week. Most trips involve work, and I’m a pretty boring dinner guest unless you want to hear about my work! I love my job, and it’s taken me a long time to believe that it’s perfectly acceptable to work long hours and become pretty narrowly focused if you want to succeed in business.

I never presume I can do everything myself. If I need the help of another professional to sell my product, develop new systems, or do the bookkeeping, I delegate the work immediately. I know my strengths and don’t waste time on tasks that are not in my skill set.

The toughest part of being a business owner is being responsible for making decisions. I think that being an artist is good training for being a business owner because we make decisions every moment when we are creating a work of art. Each time we make a mark on the canvas, we have to believe in the risk we’re taking. And we all have a process that we’ve developed to calculate that risk. Running a business is very similar.

What is your best advice for other artists?

Art is hard work. There are no shortcuts. But if you can, focus on your own creative voice. Don’t spend too much time looking at the work of other artists. Stay focused and unique—you will succeed. There is always a market for something unique.

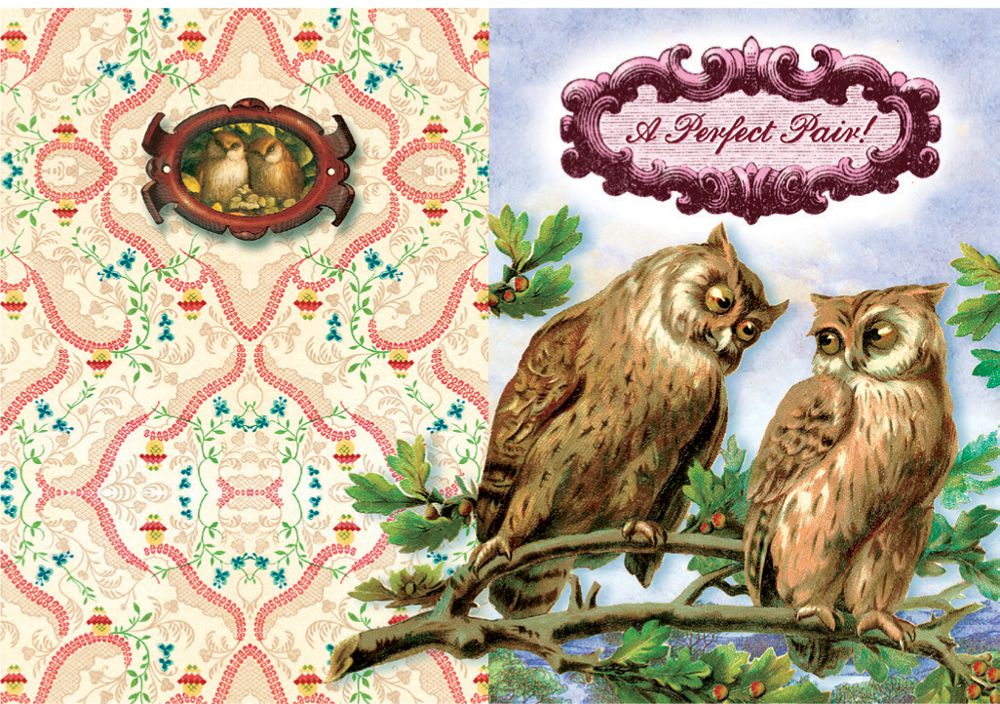

A Cartolina wedding card

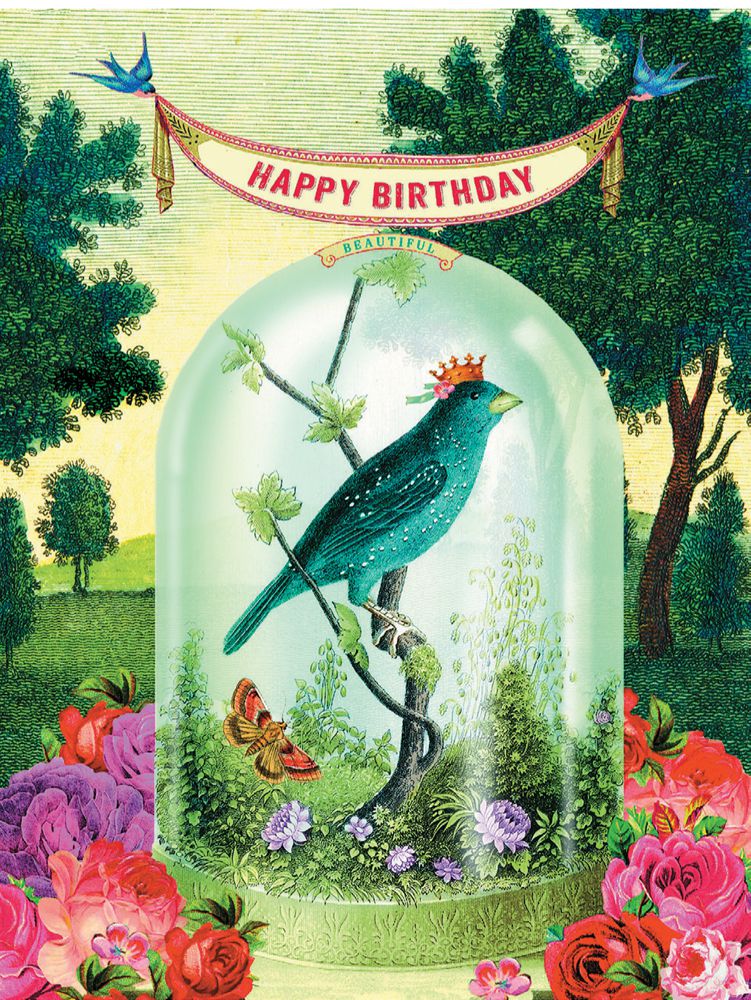

A Cartolina birthday card

Do you love to draw people doing things? Do you like to illustrate concepts and ideas? Or maybe your idea of a great afternoon involves sinking into a pile of magazines. Then consider illustrating for print publications.

Once the biggest buyer of art, print magazines have had their budgets reduced because of the recession and the fact that the Internet has grown. But I predict that the market will come back as the economy improves and readers discover that they still love curling up with an old-fashioned magazine.

This was one of my favorite areas as a working illustrator because I was able to do research and learn a great deal about a huge variety of topics; getting a manuscript to read and then immersing myself in the subject was incredibly satisfying. It challenged me to draw hundreds of things that I would normally not draw and to create visual concepts from the printed word. Initially, this work was difficult for me, but over the years, I became a concept machine and often could sketch out the rough while the art director was describing the article to me over the phone.

For this type of work, you first create rough sketches. Once they are approved by the magazine’s art director, then you go on to the finished piece.

To land this work, you need a portfolio that shows how you would illustrate magazine articles. Take articles from magazines and illustrate them.

Typical subjects include health, beauty, relationships, business concepts, technology, money, food, diet, and travel. Maps are often commissioned. Can you guess why? Because they are one thing that photography cannot do, so illustration is necessary.

How to find this work: Magazine illustration is a world all its own. Studying illustration in school is your best bet. Sign up for an online class, or take a class at your local college or art school. Also, pick up your favorite magazines and study the illustrations. Get a feel for different magazines and the kinds of styles they’re looking for. Additionally, be on the lookout for magazines that buy a lot of illustrations.

Bonnie Dain’s stylish drawings of people have landed her a great deal of editorial illustration work. This illustration appeared in The Village Voice.

Marco Marella’s style lends itself to food illustrations.

Rebecca Bradley’s illustration for Woman’s Weekly UK sets the scene in this pen-and-ink and watercolor piece.

Trina Dalziel illlustrated this personal piece. Why is this such a great example of editorial work? First and foremost, it’s a lovely drawing of a woman. Then she sets the scene with telling details—such as the vintage sewing machine, the cat on the pillow, and the wood stove—that create the mood.

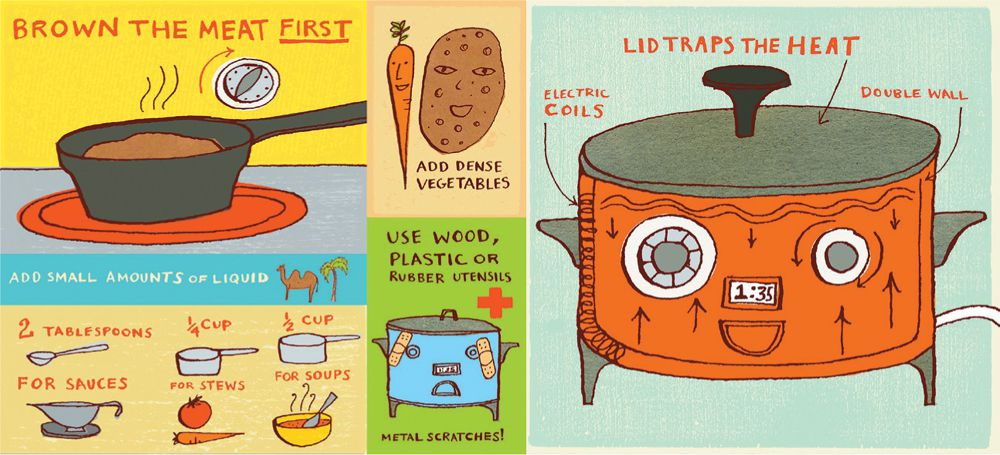

Jon Cannell’s illustration for Fine Cooking magazine is a fresh way to illustrate a how-to concept.

Moira Greto is the deputy design director of Family Fun, a magazine that has consistently bought great kid-based illustrations.

Lots of artists are dying to get to work with you. How often do you commission with a new artist?

I am always open to hiring new artists. I probably do lean on artists that I have used before, though. Mostly this is because the magazine I work for at the moment, Family Fun, has pretty specific, family-friendly needs. Many artists who I think are amazing wouldn’t necessarily be right for most assignments here. But I have kept cards and links from artists for years, in the hopes that one day I will get to work with them.

Do you like to get artist e-newsletters and postcards?

I think both can be quite effective. How else will artists be able to connect with us? I try to always open an email from an artist, but I’ll know right away if it is something I may be interested in or not. If I have time, I’ll go to their site and save the link. Postcards are similar. I’ll save it if I like it. I tend to be somewhat of a hoarder.

Editorial was hit pretty hard by the recession. Do you think magazines will rebound?

Yes, I do. They will evolve, and are evolving as we speak, but they will survive and thrive.

What’s your best advice for an artist to get work in your field?

Think about publications, companies, or industries you’d really like to work for and get to know them. Think about how your style could fit into those areas. Give yourself fake assignments that are very similar to what you see in the publications you are fond of. Get lists of the art directors that you know need to hire illustrators like yourself and contact them. Keep your messages simple and visual, and keep consistently sending work—either via email or mail. Keep reminding them of your work, and make sure the images you send have something to do with what they do. If you show you can help solve their problems, you will have a better chance of getting hired. And a sense of humor never hurts!

Moira Greto commissioned this illustration by Helen Dardik for Family Fun magazine.

Do you love to paint? Do you love rich texture? Do you like to collage and have a recognizable style? Then wall art is a category to seriously consider.

Wall art is the term for work that is sold as original paintings in galleries, as well as reproductions that you might sell online, like giclée prints on Etsy, or mass-produced prints sold to the consumer or to clients with lots of wall space to decorate, such as hotels, hospitals, and corporations.

What’s needed for this market? You’ll want to create a body of work—possibly twenty or more pieces that have a fairly consistent style and are gorgeous.

Ask yourself: Does your art look great hanging on the wall? Is there a lot to look at, to contemplate? Or might one get tired of it rather quickly? If you answered yes to the first two questions, then go for it.

Subject matter can be anything from nonobjective to abstract to realistic. Perennial favorite imagery includes all types of floral, landscapes, vases and vessels, travel, holiday, wine, coffee, and food.

Generally, our experience is that wall art companies do not want digital work because the consumer wants traditional media. Create sets of four images that work together as a grouping. Paint to the edge of the canvas. Rich, opaque paint does best. Watercolor, pencil, and black and white are harder to sell, but that is changing. Images with some recognizable subject matter used to be a must; now, modern abstracts are more in demand. Think Rex Ray. But do your own look, not his!

How to find this work: Attend or exhibit at Surtex, the Licensing Expo, or the AmericasMart (“Atlanta Gift Mart”). There, you’ll find tons of manufacturers looking for artwork for many areas, not just wall decor.

A Lisa DeJohn collage for Urban Outfitters.

Lisa Congdon’s magical world with a midcentury feel is perfect for wall decor.

Sue Schlabach is art director of the highly respected wall decor company Wild Apple Graphics Ltd.

How often do you license or commission with a new artist?

Some months it feels like every day! At Wild Apple, we are always on the lookout for new talent, whether on the Web; in galleries wherever we happen to be; or through referrals from friends, colleagues, and other artists we know. We can do two or twenty-five, projects a month. You never know when a great crop of artists will appear.

Do you ever look at sites, such as Etsy, Pinterest, print & pattern, and so on, to find new artists?

All of the above! We love to prowl around on blogs and Web shops. My inbox is chock-full of posts from the blogs I subscribe to, along with the many emails from artists and colleagues. And Pinterest is wonderful but also a deep rabbit hole that can be hard to emerge from.

Besides Surtex, which trade shows do you attend to find art?

In addition to Surtex, I have attended many other shows irregularly. Perhaps the most exciting is Maison & Objet in Paris. I’ve been to that show five or six times, and it never fails to inspire.

In addition, Printsource and Indigo are textile design shows I’ve been to in New York and Brussels. These are great trending shows and a good place to find artists who are hard workers, though it can be a challenge to make textile designs translate to wall decor. It’s a natural fit for many other household design licenses, however.

When I began at Wild Apple, we attended lots of shows. It was before the Internet and that was how we met each other, found artists, and saw what the competition was producing. The world has certainly come to our doorstep.

How long does it take you to respond to an artist?

We try to be timely (within a month), but I admit that it sometimes takes longer. We aren’t a huge company with hundreds of employees, and those of us making the art decisions like to meet to discuss a promising portfolio. Given travel and life, it can take a few weeks for that to happen sometimes. We get hundreds of submissions monthly, so we can’t respond to everyone, but if we have interest, we usually send a shout-out fairly quickly.

This lovely piece by Susy Pilgrim Waters was licensed for wall decor by Wild Apple. Florals are a huge seller, but they must be done in a fresh way.

Do you like to see mock-ups or prototypes of product ideas?

Absolutely! This shows that the artist is thinking beyond the moment of making the art (a very important moment, I might add), to the other ways that art could be seen.

How can this be a lucrative area for an artist?

There are artists who have one big hit that can be very profitable, but in my experience, the artists who have the most success are those who take the most chances, supply the most art, and don’t get hung up about the pieces that don’t get published or licensed right away. They keep their names and art in the consciousness of the customers, and after a while, they are the artists the customers ask for.

It can be hard to make a commitment to making lots of art without being sure it will sell. That’s the leap of faith that can take a year or two of hard work to pay off.

What trends are in and what’s out?

We find that images we publish for the wall need to be right on the trend edge. Right now, everyone wants butterflies and the update for birds is with birdcages. Birds are hanging on for a long time compared with some trends. Peacocks were hot on the list about six months ago, but we’re slowing on them as they are already pretty heavily in the market. Owls are heavily at retail, so we’re not developing them anymore. The next trend? On the edge are whales. Always in fashion are fresh interpretations of flowers. We’re happy that customers are open to watercolor treatments again. For the longest time, no one would even look at a watercolor painting.

Some clients love layered digital files, such as Photoshop or Illustrator files; some prefer traditional media such as paint; others can’t use painted images due to technical limitations. What do you prefer?

Layered files make designing very easy, but all our clients love work that looks painted or made by hand. If you can paint and combine that with technical savvy, by all means do. It will open doors and opportunities. That said, nothing replaces the skill of a good painter, and our classic painters are in as high a demand as ever. But because it isn’t simple to pull their images apart, some of their work isn’t licensed for certain things. In some cases, the artists are willing to paint separate backgrounds, elements, and patterns to go with the main painted art—and that helps place their art for big programs.

What’s your best advice for an artist to get work in your field?

Send a portfolio! If you don’t succeed the first time, look at our website. Look at other art in home furnishing markets. Try some things that may complement or improve on what you are seeing. Then submit again. Some of our most successful artists submitted to us several times before it was a good fit. Also know that if you aren’t selected, it isn’t a referendum on your talent—it just may be that your art doesn’t fit our current needs. Another reason to submit again!

Jillian Phillips’s A to Z piece was licensed by Wild Apple for wall decor. There’s always a market for children’s art.

Are you an art or craft store fanatic? Is your idea of a good time crafting your brains out on a Saturday afternoon? Did you know that the largest area in craft is scrapbooking, and scrapbooking manufacturers buy tons of art?

Scrapbooking tends to be its own world. It’s a mix of cool vintage ephemera, sentimental/mainstream and edgy/indie art. I love it, and I find some very exciting things happening there.

The main area of artwork that’s needed is for scrapbooking papers. These are used for scrapbooking pages and for paper crafts—and scrapbook people love their papers!

Art is also needed for products such as stickers, journaling cards (note cards that you write your thoughts on), washi tapes and trim, little ceramic tiles, and wooden baubles. It’s bought outright and licensed. If all goes well, companies want to do a whole collection with your work. Sometimes you get credit, sometimes not. Often you sell or license a number of pieces and the in-house designers make up the various products.

Buyers need all kinds of subject matter, from various holidays and celebratory occasions (birthday, wedding, etc.) to just lots of pretty imagery like you might find at a vintage shop. French vintage is very big right now, as is steampunk.

How to find this work: Go to your favorite art store and check out the scrapbooking department. Get names of companies you love. Attend the Craft & Hobby Association show, go to the workshops and lectures, and get to know the companies.

This piece by Macrina Busato is a great example of a look that’s trending in scrapbooking.

Jillian Phillips designed these papers for scrapbooking as part of my Ruby Violet line. She entitled her collection Yuki.

Tami Indra is the creative director of Prima Marketing, a consistently trendsetting company that creates stunning products for the scrapbooking and craft markets.

What websites do you look at to find new artists?

In this business, it is important not to develop tunnel vision. To stay current with today’s trends and to scout new talent, I regularly visit Etsy, Pinterest, and the print & pattern blog.

Do you like to see mock-ups or prototypes of product ideas?

Absolutely. Submission of a mock-up or a physical sample is the best way to move your idea from concept presentation to the Prima catalog.

Can you give an example of a great presentation that would help an artist land work with you?

My mind is not easily blown, but a good attempt is to present a unique and fresh concept on an idea board along with labeled loose samples that I could keep for reference and review.

Some clients love layered digital files, such as Photoshop or Illustrator files; some prefer traditional media such as paint; others can’t use painted images due to technical limitations. What do you prefer?

It depends on the product category. If we work with pattern papers, it’s helpful to get all artwork in Adobe Illustrator, as it is easier for us to develop. As for embellishments, real samples are preferred.

How lucrative can scrapbooking and craft be for an artist?

Commissioning and licensing can be very lucrative. Good product performance leads to repeat licensing. This is also a good way to build your own brand as a designer, which can launch an artist into multiple lucrative careers.

What do you need to see to know that you can have a long-term working relationship with a particular artist?

Every artist has his or her own style and personality; this makes every working relationship unique, whether it’s long- or short-term. However, an open mind and a willingness to receive constructive criticism is a great virtue to have as an artist.

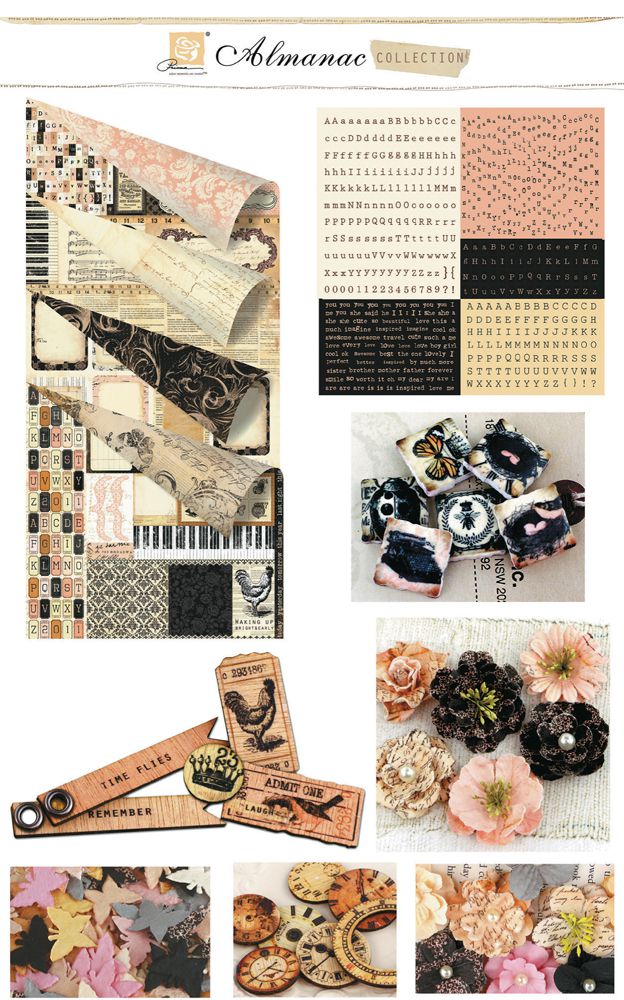

Prima’s vintage, steampunk-style Almanac collection for the scrapbooking market. Notice how the colors are consistent throughout the products.

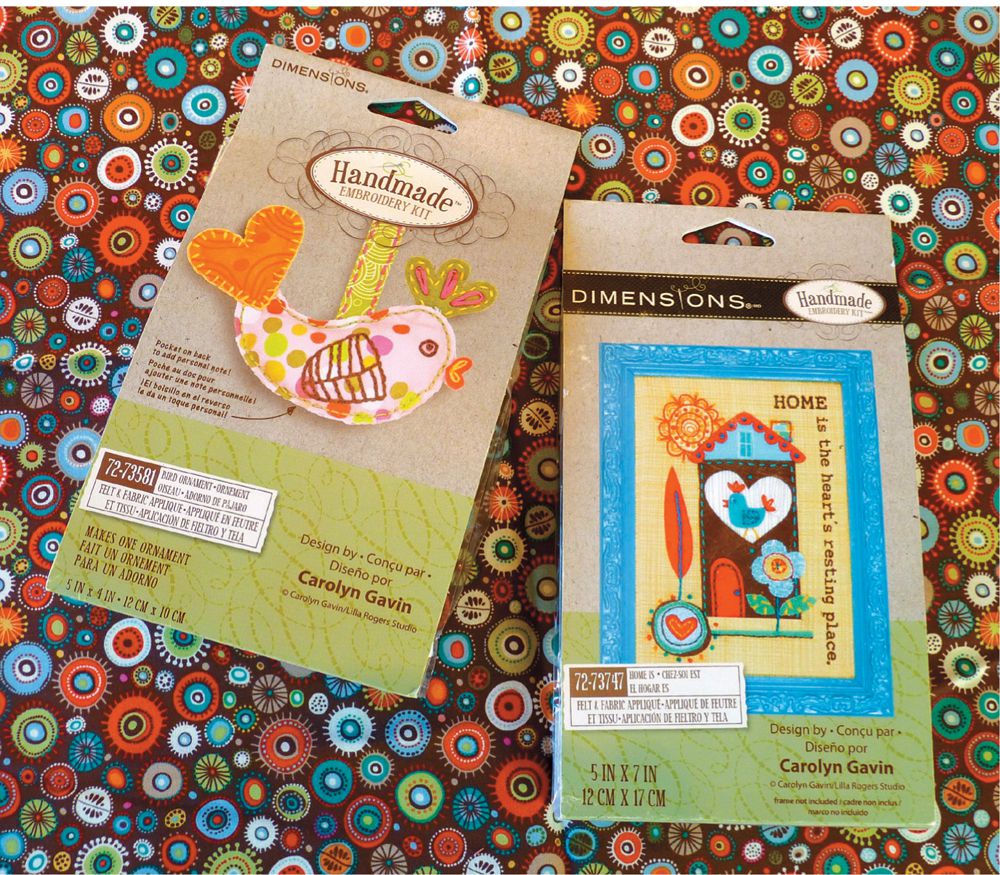

Tyra Derr is the art director of Dimensions Needlecrafts, a company that has taken a traditional craft form and injected it with contemporary designs. Needlecraft is an exciting new growth area, and Tyra has been instrumental in making that happen. They do punch needle, cross-stitch, embroidery, needle felting, and felt appliqué.

How often do you license or commission a new artist?

We have a large pool of existing artists and agencies that we license with on a regular basis. It varies year to year, but on average we would need fifty to sixty designs annually. We introduce three lines a year, so that means we contract new work every three or four months.

What trends are in and what’s out?

Well, I keep wanting to say owls are out, but I keep seeing a lot of nice variations and styles, and I think they are still selling at retail. Sayings and typography are definitely still in. Personalization and customization are always popular. Flowers, butterflies, and other nature-related designs are evergreen; the styles themselves just need to stay updated (for example, the current collage style can make a traditional butterfly design look fresh).

What format do you prefer for artists’ work?

We generally prefer layered digital files. No matter how perfect the art itself is, we usually need to make some modifications to make it more suitable for our purposes (needlework/textile kits).

What’s your best advice for an artist to get work in your field?

Send new art regularly (every couple of months). We review art every day, and if the timing is right, a new artist with a new design will get picked up for one of our lines.

It may be easiest for a designer starting out to try to get placement with an agency first. I know in our case, we have a “big, bad, scary contract,” and I would think many new designers who do not have legal counsel would be hesitant to sign such a contract. Working through an agency to start would certainly give them more security.

Persevere and don’t give up!

Needlecraft products with art by Carolyn Gavin for Dimensions. The background fabric is by Carolyn, too, for P&B Textiles.

Artist and illustrator Claudine Hellmuth does workshops, illustrations, a craft line, an online course, and HSN. I love that she takes risks and has done such a great variety of things with her own special brand of charm.

You do workshops, illustration, a craft line, an online course, and HSN. What’s the most lucrative?

Teaching the live workshops and classes has been the biggest moneymaker for me in my business for many years.

What area is not as lucrative as some may think?

The product lines and licensing are not as lucrative as they appear from the outside. But they are a building block to my business and an aspect of it that I hope to grow and use to bring in more income in the future.

How did you get your craft line with Ranger?

I met Ranger at the Craft & Hobby Association (CHA) Conference and trade show and began demoing in their booth in 2006. After a couple of years of working together, we decided that it would be great to bring my paint knowledge to their product line, and so we partnered on the Claudine Hellmuth Studio line of paints, mediums, canvas, and brushes. I have been painting since I was fourteen. I got my B.F.A. in painting, so paint is very close to my heart. I have strong feelings about what a paint should be like, and Ranger was able to create a paint that I am really excited to call my own.

How did you get the opportunity with HSN?

Through contacts that I met at the CHA show. All the networking at the CHA show has been good to me!

How was doing TV?

I’d done TV a few times on HGTV, DIY, and PBS crafting shows. And I was on the Martha Stewart Show in 2007. But being on HSN is very different from being on any other type of crafting TV because the focus is on the product, not the personality. Also, there are a lot of cameras, and on every other craft TV show I have been on, they always tell you never look at the camera—always look at the host. For HSN, they want you to look at the front-facing camera to talk to the viewers. It’s still something that I’m getting used to—that and the earpiece where they are talking in your ear while you are on air.

On HSN, you have just a few minutes to make as many sales as possible. How do you deal with the pressure? What kind of preparation do they give you?

You do take a class at HSN, and they go over the cameras and the in-ear mic and a little bit about the sales. Mostly, though, they just want you to be real and talk in a real way about your product. No hard sales, PR, used-car salesman type talk. You just talk about why you made it, what’s great about it, and why people would want it, and show lots of samples! Since I design my own products from start to finish, I could talk about them all day long.

What do you think makes a good product for HSN?

The HSN customer likes value (don’t we all?), so they want a lot of goodies in each of the kits.

Every artist experiences the ups and downs of having his or her own business. What do you advise to others just starting out—or even those who have been in the business a long time?

It took me a long time to realize that the money worries never go away. I have been doing this for twelve years and have been making a good living. But each year I panic, wondering, “How will I make enough money this year?” and “Will I end up working at Starbucks?” But each year, it works out. I think when I was starting out, I thought that at a certain point I would just stop worrying about the direction of my business, and I would have it all set and just keep going. But the way our businesses are today, they’re always evolving, always changing, and you have to grow and change with your business to keep it thriving.

What is your best advice for other artists?

I would say to stay true to yourself. As an artist in business, you’ll have a gazillion people telling you what you should do and what your work should look like. Keep your vision and stay true.

Photo by Claudine Hellmuth.

Claudine’s products are sold in this very cool case.

Trade shows allow sellers and buyers get to together. They’re huge events that exist solely for the purpose of bringing together the commercial community of a particular market. They often include invaluable conferences and workshops for artists and designers on the business end of the market. You’ll learn a lot and meet a lot of people if you’re open and ask questions.

Do I have to go?

If you want to jumpstart your career in a particular market, then yes, you should consider it. But first, walk the show. Look, talk, and learn. Then consider exhibiting. Not every market requires you to attend a show. See the chart on the following page.

Are they expensive?

Yes. There’s the booth fee, which is usually the biggest expense. Also factor in travel, hotel, meals, booth set-up, prints or portfolios, and staff or a friend to help. The trade show websites usually offer great hotel deals.

Our own Susan McCabe, agent at Lilla Rogers Studio, taking a breather at a trade show. Our booths feature seven-foot-long banners.

Walk vs. exhibit?

Walking a show like the Licensing Show, Printsource, CHA, and Surtex, is minimal in cost, and it allows you to see what kind of work is being sold by other artists.

How to do it

The whole point of the show is to make contacts, so getting and saving business cards is key. You will meet so many people that even at the end of each day, it’s hard to remember who is who when you look at your pile of business cards.

Artist Suzy Ultman and agent Ashley Lorenz at our booth at the Surtex trade show. The rack holds a great deal of products, which can be useful to show when talking with clients. Note Suzy Ultman’s stuffed animal prototype hanging from the wall.

My technique is to bring a journal or notebook and staple or tape one card to each page of the journal. Immediately jot a note like, “Wants me to send my penguin print ASAP. They manufacture backpacks.” “Check this company out.” “A good person to get advice from.” “I should send them my spaceship drawings.” Sometimes, I’ll write down thoughts, observations, and any emotions I may be feeling. There’s a lot to process, and journaling is a great way to stay in touch with your feelings. It’s common to feel overwhelmed, excited, discouraged, motivated, and alienated. At each meal, or the end of the day, go through your journal and elaborate on each card. Give a little more information if you think of it.

Then, in the back of the book, I write down my hottest leads or most appealing next steps. The whole key is follow-up. That way, when I get back the studio, I have a game plan. Since we represent a lot of artists, when my studio exhibits at a show we have a large booth that is fully staffed. We have a great follow-up system in place that allows us to take fast action on leads and sales. We have luggage packed ahead of schedule with check sheets and packing info.

During and after each show, we jot down ideas on a clipboard entitled, “What to do next time.” It’s where we note anything to do differently, since each time we learn more about what works and what doesn’t. We do about three shows a year as a studio, and I do reconnaissance by myself on a few more shows per year. Please allow a few years to really start benefiting from exhibiting, as it takes time to build relationships. Below, refer to the Trade Show Market chart showing which shows are the best to attend for the corresponding market.

Bolt Fabric | |

| Surtex Show | × |

| Licensing Int’l Expo | |

| Americas Mart | |

| Print-source | × |

| Première Vision | |

| Quilt Market | × |

| CHA | |

| NY Gift Fair | |

Apparel | |

| Surtex Show | × |

| Licensing Int’l Expo | |

| Americas Mart | |

| Print-source | × |

| Première Vision | × |

| Quilt Market | |

| CHA | |

| NY Gift Fair | |

Gift | |

| Surtex Show | × |

| Licensing Int’l Expo | × |

| Americas Mart | × |

| Print-source | |

| Première Vision | |

| Quilt Market | |

| CHA | |

| NY Gift Fair | × |

Home Decor | |

| Surtex Show | × |

| Licensing Int’l Expo | × |

| Americas Mart | × |

| Print-source | × |

| Première Vision | × |

| Quilt Market | |

| CHA | |

| NY Gift Fair | × |

Paper Goods | |

| Surtex Show | × |

| Licensing Int’l Expo | × |

| Americas Mart | × |

| Print-source | |

| Première Vision | |

| Quilt Market | |

| CHA | |

| NY Gift Fair | × |

Wall Art | |

| Surtex Show | × |

| Licensing Int’l Expo | |

| Americas Mart | × |

| Print-source | |

| Première Vision | |

| Quilt Market | |

| CHA | |

| NY Gift Fair | × |

Scrapbooking and craft | |

| Surtex Show | × |

| Licensing Int’l Expo | |

| Americas Mart | |

| Print-source | |

| Première Vision | |

| Quilt Market | |

| CHA | × |

| NY Gift Fair | |

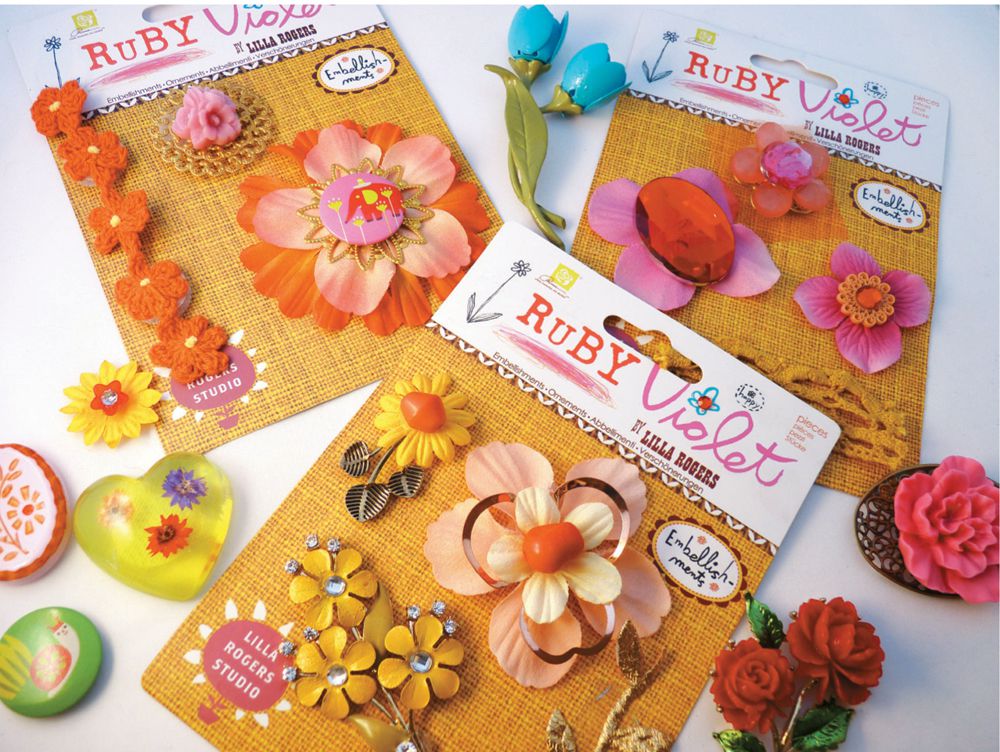

I want to show you how my craft line, Ruby Violet, came into being because my journey illustrates a great deal of what we’ve been talking about and what you’ve been exploring in this book—such as creating work rituals, finding your passion, and people buying your joy.

In this section, you’ll learn how a passion can be brought to market and explore how to figure out what you really want, pitch your idea, and deal with the various twists and turns that happen along the way.

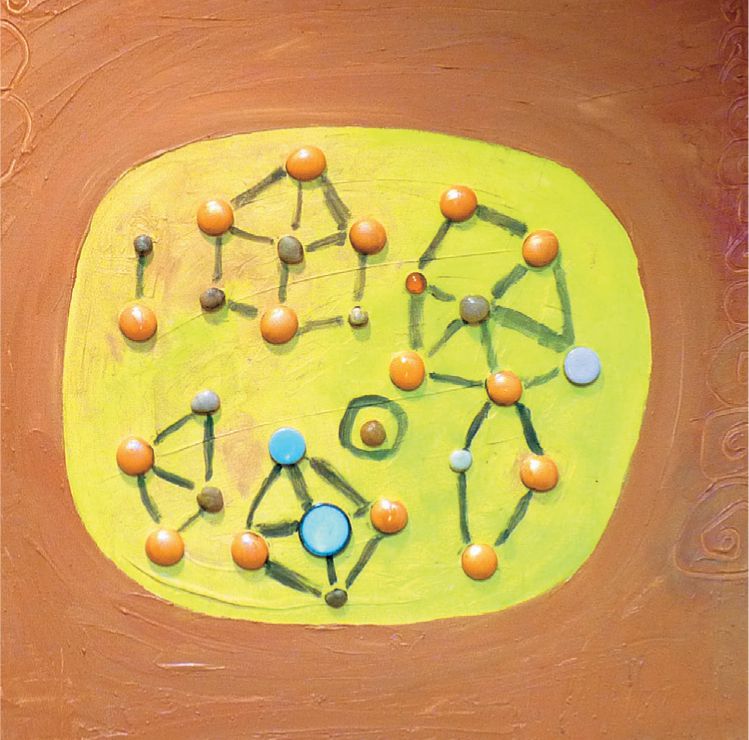

A number of years ago, I was working on an assignment for Yoga Journal when I was drawn to the idea of incorporating 3-D elements into my work. I began using mosaic tiles, screen mesh, fabric, and stones in my editorial jobs and personal paintings. Who knew this simple act would be the beginning of a whole new creative chapter in my life?

Around the same time, my dear friend Sue, a former scientist, and I would get together and make jewelry. One summer, we decided to go to an exceptionally cool bead shop in Martha’s Vineyard and take a three-day craft sabbatical. The sabbatical turned into an annual retreat, and it really stoked the passion. I became more and more obsessed with jewelry making, combing junk stores and bead shops and flea markets looking for bits and pieces to use in my work.

On one of these excursions, I saw a beaded cuff at a store in Harvard Square and fell in love with it. That set off my obsession with making cuffs.

Illustration development for Yoga Journal. This is when I began to obsess over 3-D elements: mosaic tile, fabric, sea glass, buttons, gem cabochons, fabric, rickrack, and stones.

Even my paintings were starting to get 3-D elements. I love sticking glass and ceramic bits onto my canvases. Then I connect the dots.

Most weekends and even on vacation, I would putter with my jewelry. Putting on music and making things was a piece of heaven. At that point in my life my kids were becoming more self-sufficient, so I had more time to give to my hobby. I stayed motivated and put in my “10,000 hours” thanks to the support and enthusiasm of my friend Sue and by taking workshops together on new techniques. We took a class on bronze clay in Rhode Island, steampunk jewelry and riveting in Maine, and beaded crocheted necklaces in Cambridge. I had no idea where any of this was going, but it was a great stress reliever and just kept being fun. My husband, an ER doctor and metal sculptor on the side, was always enthusiastic. A master of tools and techniques, he was great at helping me riddle out technical issues.

A few of the cuffs I made. I love the entire process: cutting the leather, stringing the briolette flowers, firing the silver-clay charm. My buddy Sue was always there when I got stuck with technical aspects. As a former bench scientist, Sue is detail-minded; lucky for me, she has a ton of patience, too.

The jewelry obsession continues.

Here I am wearing my Ruby Violet eyeglasses holder and contemplating my next project.

Right photo by Sharon Jacobs.

Susan McCabe, an agent here, used to be an art director at Harvard Business Review. We first met several years ago on the playground (aka the old girls’ network) where we’d bring our kids.

Before she was hired here, Susan would come to the studio and see what I was doing. One day, she came by and saw my cuffs lying on my worktable. She said, “Oh my god, I love these! I want to sell these.” I said, “I don’t think there’s any money in it.” I’d fired the metal clay beads in my kiln, cut the leather by hand, attached the snaps, and strung the beads into briolette flowers. With all the time and expense I’d put in, I’d be lucky to net a few dollars per hour.

I said, “It’s not lucrative because it’s too time-intensive, and oh by the way, I’m running an agency full time, representing our artists.” And I blurted out—and I’ll never forget this—“One day I would just love to design these like crazy and send them off to a company and have the company make and sell them. That’s my dream. I don’t know when, and I don’t know how, but that’s my dream.”

A short time later, we were looking to hire another agent, and as luck would have it, Susan was available. Some time later, we made a plan for really bringing this work to market. We all thought this was getting to be something that we would pitch to one of our clients.

First, we had some questions to answer: Who was the market? Would this be finished jewelry people would buy, or would this be craft jewelry where people could make their own items? I found the whole burgeoning craft movement compelling—what was happening with Etsy and all the indie craft shows, including Bazaar Bizarre and Renegade. I saw the mass-market craft industry had potential to hip up. So I chose craft jewelry over retail jewelry.

The next step was to find a craft manufacturer that shared my vision. I would lie in bed in the evening with my iPad and peruse all the craft manufacturers. I would hunt them down to get a feel for who was making a lot of embellishments and who might be open to a cuff idea, since I didn’t see anyone else doing it at that time. I made a short list, and Susan and I made a plan to go see one of our favorite craft companies that we already worked with.

In the meantime, as it happens when the stakes begin to get higher, I had moments when I would get a bit nervous. My studio manager and trusted friend and colleague, Julia Parker, was always there to cheer me on and calm me down. She is better than drugs, and she’s legal. She’d find things she loved about what I was doing, like a pretty color combination. It kept me going.

Now that we had a company in mind, I needed to create my pitch. The most important thing about a pitch is clearly presenting what you ultimately dream of having, rather than leaving it to the potential client to figure out. I commissioned one of my artists (and one of my favorite graphic designers, who also helped design this book), Suzy Ultman, to design the packaging, and I created a whole presentation showing my dream—a line of cuffs, a line of embellishments, and a line of necklace kits based on repurposed vintage pieces, requiring no tools. I got my daughter, who was in middle school at the time, and some of her friends to help assemble the pieces and the packages. I created some mood boards to give a range of some styles I was capable of producing from soft and girlie to indie and vivid. At every step, Julia always took the time to rave and show her delight with what I was working on. How valuable she is to me!

I gave a several-hour pitch to the creative team. They said, “Well, would you be willing to do it without your name on it?” This generally gives a company more flexibility. They’re less dependent on the artist, and they have ownership of the brand so they can keep creating new product even if the artist tires of it. I said, “I really want to hold out for having my name on it.” I envisioned branding my name, my style, and my Ruby Violet product lines to open more doors for me. It was a risk, but I was pretty clear about my goals.

I got the feeling that it wasn’t going to work out. So on the ride home, although I was crushed, I said to Susan, “Okay, what’s Plan B?” We agreed that Plan B would be to pitch to manufacturers at the Craft & Hobby Association show in Los Angeles, which was coming up in a few months. To be honest, I didn’t know if I had it in me. But as my mother often said, “Some people give up right before their success.”

I created a “no-tools-required” necklace technique that would allow all crafters, even nonjewelry people, an easy point of entry for necklace making. The system uses brads and holes to create a “skeleton.” Then, pieces can be mixed and matched and glued on top. Left, the parts included in the kit and above, the finished necklace.

So it was back to the drawing board. I already had gotten great advice on pitching trade shows from the delightful Cathie Filian, a speaker I’d met at a Creative Connection event in Minneapolis. She told me to ask for the CEO or the owner, tell them you’re a designer and you’ve created a line, and that you would like to pitch it to them. She also told me that if you pitch to one person and they say no, you say, “Next!” and go find the next person. Her words of encouragement gave me strength.

I flew out to LA with photos of Ruby Violet on my iPad and a little bag of my prototype packages. I was nervous, I was excited, and I was second-guessing myself. Even though I can pitch any of my artists to the biggest CEO in the world and not have a single nerve, everybody knows pitching your own stuff is much harder. One of my artists, who lives in LA, the brilliant and fun Sarajo Frieden, joined me at CHA and was a wonderful companion. I pitched to a handful of companies, with responses from “Great!” and “Interested in a deal!” to “The person to speak to is not here.” And some companies weren’t interested because they did all their design in-house.

That night, I went back to my hotel and had a good, long think. My goal for the next day would be to simply and calmly wander around the show and only go to a company I really, really felt would be a great fit. Not a company I thought might be simply capable of manufacturing my product. It would have to feel like it was a match made in heaven.

I would take all the time I needed to find that company; I’d go with my gut to find a good fit. And the next day, that is exactly what happened. A week previous, Susan McCabe had advised, “Allow things to happen at the show,” and that’s what I did. Allow things to happen: my mantra. I got back in touch with the idea that this was supposed to be fun, after all.

I saw a booth that I fell in love with, and—long story short—they saw my work and were very enthusiastic.

Their booth was magical and feminine and exquisitely beautiful, and it had an indie look. It was covered in gorgeous scrapbooking papers, embellishments, charms, and lace. There were vintage dress forms covered in silk flowers, embellishments, and jewelry.

The Ruby Violet line presents a myriad of possibilities. No two projects come out the same!

I said, “Hi, I’m Lilla Rogers. I’ve designed a craft line and I’m wondering if I could pitch it to your owner or CEO.” “Oh, sure, just a minute.” The owner sat down with me right then and there and pulled in the creative director. I showed them everything, and to my delight, we started talking details. Shortly after the show, I signed a contract.

It helped tremendously that I knew what I wanted and that after having pitched so many times, I felt comfortable pitching it. I was hoping for a big line with a large number of products, some creative control, a long-term relationship (like a three-year contract), and a great working relationship. I was looking for a royalty situation. I didn’t want a company that was just going to pick up a few designs every so often. It was better that we both knew that from the beginning, to make sure we were on the same page.

The cuffs, rubber-stamped

The necklace kit

The actual Ruby Violet product: embellishments

As I write this, here it is a year later, and I have more than 150 products with Prima, and I’m able to do what I had hoped for. With the guidance of Prima’s creative director, I design and ship them off, and they manufacture and sell them. I am happy.

I have the fun of working with the creative director designing collections and going to the trade shows to teach my product. My products are sold around the world. I love where this has led: Next I’ll be making short Ruby Violet how-to videos, which will be a fun new thing. I look forward to teaching Ruby Violet and designing the next collections.

Here’s how I’ve leveraged my success to be an asset to my artists. Besides commissioning Suzy Ultman to do the first package design and help me with the scrapbooking papers, I licensed art by one of my artists, Hsinping Pan, for buttons as part of the collection. I’ve worked with one of my artists to create a collection that I pitched to Prima, and they fell in love with and licensed her work on an entire collection from washi tapes to scrapbooking papers. It’s called Yuki for Ruby Violet, and it’s by the supertalented Jillian Phillips. Yuki is sold worldwide. I plan on pitching other artists over time. This allows me to have yet another market for my artists. As I always tell my artists, what’s good for one is good for all. My success brings my artists success. And now, I’m able to be their agent and a client. I’ve commissioned art by some of my artists. Cool.

The next collection. Retail collections need to evolve to delight the consumer with a new look. Here, I designed a package that married French vintage with Ruby Violet, using deeper colors in the red, plum, and aubergine family.

Jillian Phillips’s Yuki Collection for Ruby Violet.

As you read about my journey, did you notice how much support I received? I did not make this happen all by myself, and I make a point of thanking those who help and support me. When you venture out into the world with your ideas and art and dreams, know that you are taking lots of big, scary risks. You are brave to do so, yet you will benefit from support of all kinds.

Mimi Kirchner is a star of the handmade market, selling a line of crafts, primarily dolls, through Etsy, her blog, and galleries. Her one-of-a-kind work made from rescued fabrics combines very traditional folk art faces with in-your-face, edgy, tattooed designs. She was recently commissioned to design a line of dolls for Land of Nod and has been offered book deals.

What’s the most fun and exciting aspect of your career?

Mostly I get to do whatever I want. Of course that is the scariest part, too. And I have fans.

What area is not as lucrative as some may think?

Art gallery shows almost never sell anything. Not sure how they survive! The craft shows are usually not big moneymakers for me, but I do them for other reasons—to introduce new people to my work, to watch people’s reactions to my dolls, to interact with other artists, to take a gamble on getting media attention. You never know who will come through your booth. The challenge is finding the right show. There is nothing worse than being at the wrong show where no one connects with your work at all.

Which craft shows do you recommend and why?

I do shows that are classified as indie craft shows, as opposed to fine craft shows. The indie shows attract a younger crowd of Internet-savvy buyers. They are more likely to have seen my work online, or if they’ve never seen it, they are comfortable shopping at one of my online venues at a later date.

I love the Renegade craft shows. I have participated in the Brooklyn show and the Chicago show. The organizers are incredibly supportive of the artists and make the events fun for everyone. I did the Boston Bazaar Bizarre this past December and had a blast. That is another show where the organizers appreciate and support the artists and make their event so much fun that people look forward to it all year.

Mimi Kirchner with her handmade dolls.

Photo by Peter Hyde.

That said, I don’t do very many shows. I try to keep it to about four a year.

How important is making money?

If money were the most important thing, I wouldn’t be doing what I am doing.

When I first started on the dolls, I spent a few years doing very labor-intensive pieces. I was not willing to part with them unless I was able to sell them for a high price. I found that not selling any of the dolls was discouraging even though I enjoyed the process and got a lot of positive feedback through my blog. So yes, money is important as validation—that people are willing to open up their wallets for my artwork.

As a creative person, you take a lot of risks and put yourself out there. Who supports you and how?

I am part of a group of creative microbusiness people, most of whom sell online and at markets. We meet once a month and talk about all the things that make our lives wonderful and crazy. The group is a fantastic resource. It seems that no matter what the question or the problem is, someone else has a similar experience and some insight. We have a venue at which to brag and moan.

What is your best advice for other artists?

Work really hard. Don’t wait for inspiration. Strive to have friends of all ages. Don’t expect to get rich. Be wary of other people telling you what you should do. Figure out what you are good at and love and do that. Do a job where you love the tools and supplies—it makes shopping and business-related expenses so sweet!

Ayumi Horie’s high-end handmade ceramic pieces are gorgeous. She sells her work online and in galleries and shops, teaches workshops, and lectures at colleges.