JOHN F. KENNEDY

1961–1963

JOHN F. KENNEDY BECAME president at forty-three, the youngest man ever elected. Despite fourteen years in the House and Senate, he had a slender record of legislative achievement. He still had a lot to learn about politics—especially since he took office during the hottest years of the Cold War.

The fight with the Soviet Union for global supremacy dominated Kennedy’s presidency. In 1961, JFK launched the disastrous invasion of Cuba’s Bay of Pigs, which was supposed to overthrow the newly installed Communist leader, Fidel Castro, and Nikita Khrushchev erected the Berlin Wall, dividing the great German city. The next year saw the Cuban Missile Crisis. Failure was not an option: if diplomacy failed, America could be decimated in a nuclear war.

Cold War references riddle Kennedy’s doodles—mainly in the form of words. Where Hoover’s doodles are abstract and geometric and Eisenhower’s concrete and representational, Kennedy’s are heavily textual—reflecting his verbal, cerebral nature. He often repeats a word or phrase several times and sets each one in its own individual box, as if to contain his nervous energy. In a doodle he made during a January 18, 1962, phone conversation with David Ormsby-Gore, the British ambassador, the word Kennedy writes is “awkward.” One subject of his discussions with Ormsby-Gore (and with Carl Kaysen, the national security aide whose name JFK has also scrawled) was the disposition of British Guyana, which had recently elected a Marxist premier—an awkward situation, to be sure, as JFK and Khrushchev competed for the allegiance of Third World countries.

Beneath his outward calm and self-confidence, Kennedy could be high-strung. He fidgeted in meetings. “He radiated a contained energy, electric in its intensity,” wrote Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. “Occasionally it would break out, especially during long and wandering meetings. His fingers gave the clue to his impatience. They would suddenly be in constant action, drumming the table, tapping his teeth, slashing impatient pencil lines on a pad. Jabbing the air to underscore a point.”

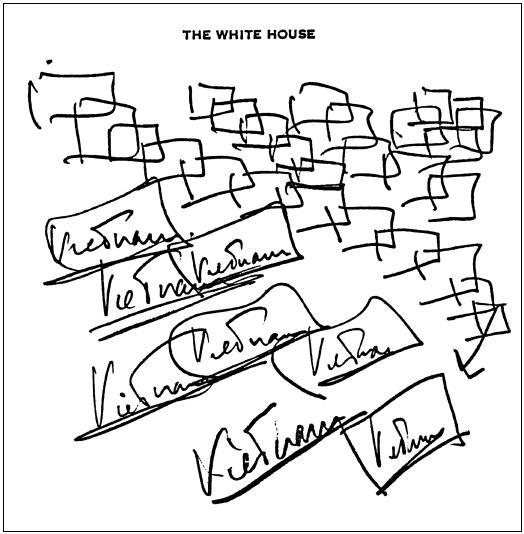

In some doodles, Kennedy wrote one or two or three words over and over, in a tense, almost obsessive repetition—as if he were trying to work through whatever anxious situation was confronting him at the moment. Although one should engage in presidential mind reading with the utmost trepidation, it seems safe to say that in this doodle JFK was concerned about Vietnam. That he encased the word in domino-like rectangles, one tumbling into the next as if spilling across the page, was more likely a felicitous accident than a deliberate visual pun on “domino theory,” a phrase that had been in circulation since the 1950s.

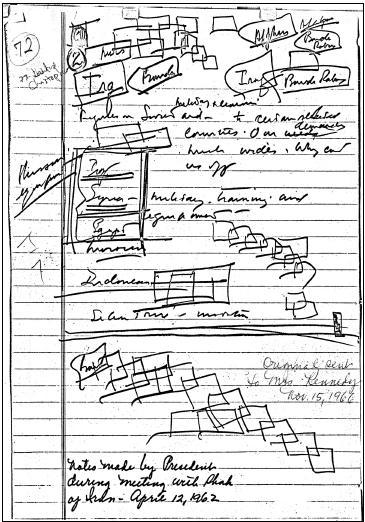

The same motif of boxes—frequently filled in with the names of Cold War hot spots—appears in many of Kennedy’s notes. Sometimes he draws a chain of boxes, one overlapping with the next, their intersections resembling a row of crosses in a cemetery. In this doodle, Kennedy is focused on the Middle East. The early 1960s witnessed political turmoil in the Arab world. A 1961 coup d’etat brought a Baathist regime into power in Syria; in 1963, the same would happen in Iraq.

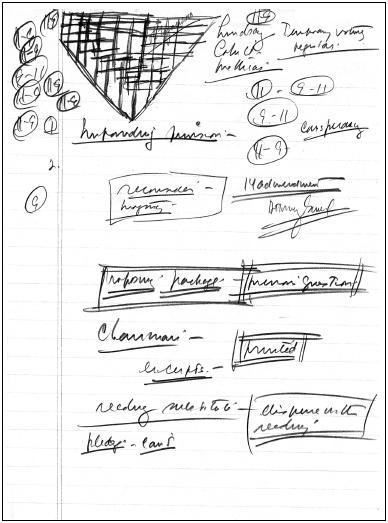

Given the number of bizarre conspiracy theories still swirling around Kennedy’s assassination, the doodle below—with “9-11” written repeatedly and the word “conspiracy” underlined—is chilling at first glance. On closer inspection, the inversion of the numbers to “11-9” elsewhere on the page and the list of congressmen’s names at the top suggest that the numbers refer not to a date but to the possible outcomes of a committee vote.

Although foreign policy was Kennedy’s main interest, at least at the start of his presidency, his doodles occasionally drift elsewhere. During this April 5, 1962 meeting, Kennedy was apparently thinking not only about communism but also about cheese.

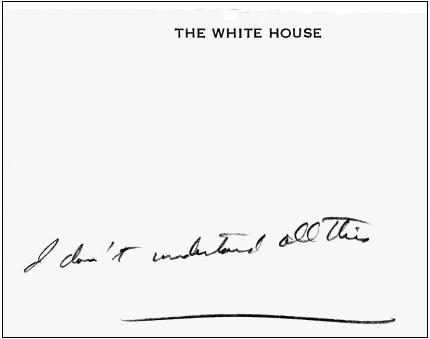

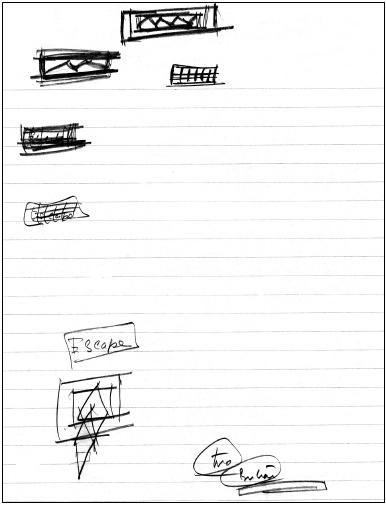

Kennedy was known for his “grace under pressure”—a phrase Ernest Hemingway coined and JFK liked. Whether at his live televised press conferences (which he was the first president to hold) or at gatherings of the Executive Committee that met during the Cuban Missile Crisis, Kennedy usually maintained his poise and his ability to think clearly. But the calm sometimes cloaked his uncertainty—an uncertainty the young president may have disclosed in his doodles, as in this where he confesses not to understand the problem at hand, and in the following one, where one can imagine him giving voice to fantasies of escape.

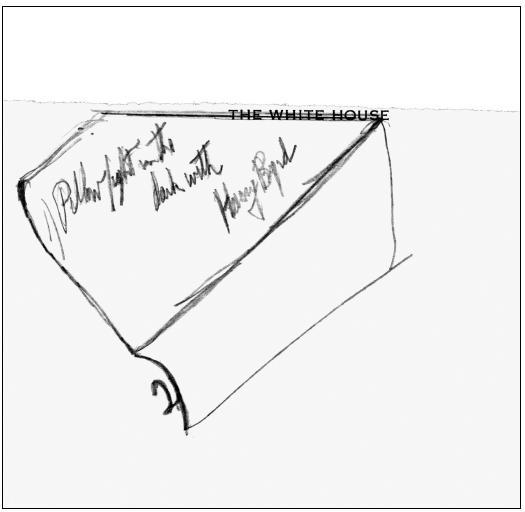

Kennedy resorted to a somewhat strange yet intriguing metaphor in contemplating a showdown with his frequent antagonist Harry F. Byrd of Virginia, a conservative Democrat and segregationist who had served in the U.S. Senate since 1933 and whose seniority gave him substantial power. The two often were at odds over civil rights.

Pillowfight in the dark with Harry Byrd

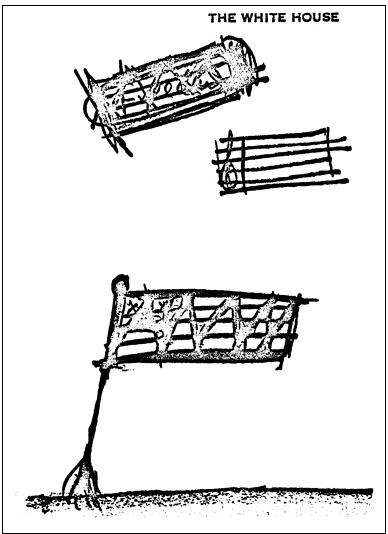

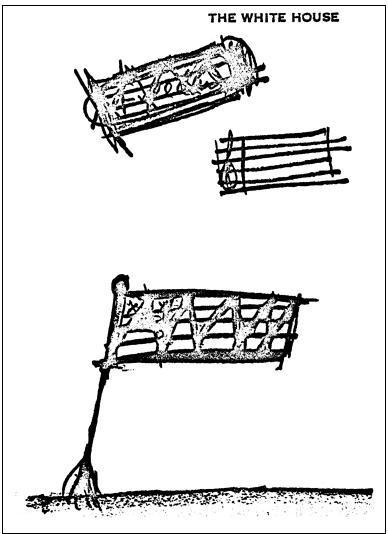

Some of Kennedy’s doodles reveal his wit and whimsy. Here, after compulsively drawing rectangular boxes striped with horizontal lines, he playfully turns those rectangles into two very different images: a musical staff with a treble clef at the left and a modified American flag.

Kennedy has been viewed as both a brave Cold War leader and a rascal, an inspiration and a rake. Likewise his doodles are open to vastly different interpretations. The image below might be a torch of freedom being passed to a new generation. Or it might be the ornate pillar of a canopy bed.

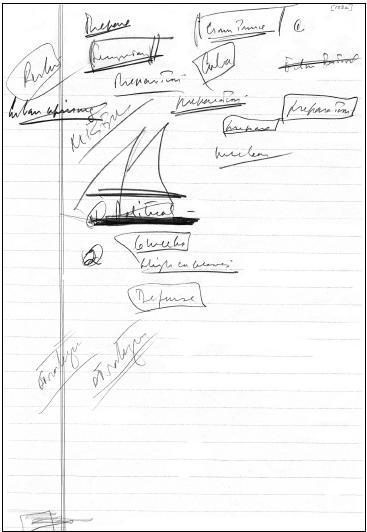

Apart from his words and boxes, the image that recurs most often in Kennedy’s doodles is the sailboat. In many instances, such as this drawing, he sketched his own sloop, the Victura. Built in 1932, entirely of wood, the 26-foot boat was a gift to JFK from his parents on his fifteenth birthday. He raced it as a young man, and it was on this boat that he taught Jackie how to sail.

Kennedy drew this doodle during the height of the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962. “Blockade Cuba!” he reminded himself, much as he might have reminded himself on a slower day at the office to pick up the dry cleaning. During the crisis, Kennedy used Navy ships to blockade the island nation to keep out Soviet missiles. The Victura, however, played no role in the quarantine.

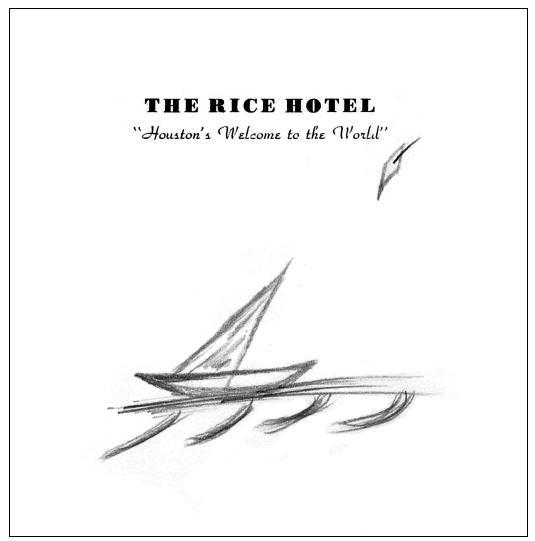

Kennedy was never happier than when he was by the ocean. “I really don’t know why it is that all of us are so committed to the sea, except I think it is because in addition to the fact that the sea changes and the light changes, and ships change, it is because we all came from the sea,” he said at a 1962 dinner celebrating the America’s Cup, the international yacht race. “And it is an interesting biological fact that all of us have, in our veins, the exact same percentage of salt in our blood that exists in the ocean, and therefore, we have salt in our blood, in our sweat, in our tears. We are tied to the ocean. And when we go back to the sea, whether it is to sail or to watch it, we are going back from whence we came.”

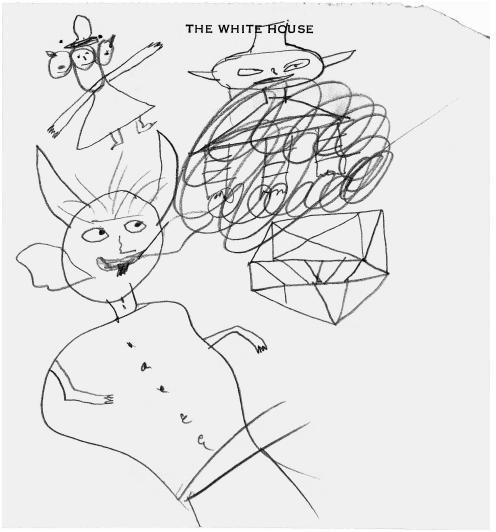

Kennedy probably sketched this, his freest and most elegant doodle, the night before he was murdered. The stationery in from Houston's historic Rice Hotel, where the president dined and attended a meeting before spending his last night in Ft. Worth. Like the photographs of Kennedy sailing off Cape Cod, this drawing lets one imagine the late president at peace as he pictured himself free on the Atlantic waters.