LYNDON B. JOHNSON

1963–1969

BOTH EISENHOWER AND Kennedy had secretaries who saved their drawings, but Lyndon B. Johnson’s White House was probably the most dedicated to doodle collecting. After each meeting, a staff member would round up whatever notes were left in the room, even if they had been balled or ripped up.

Every scrap on which LBJ scribbled was to be preserved. According to the journalist David Halberstam, Johnson was partly motivated by his respect for history and partly by his own grandiosity. “On board the presidential jet,” Halberstam wrote, “he often doodled as he spoke with reporters, and if he left to talk with someone else and noted a reporter moving to pick up a scrap of presidential doodle, he did not find it beneath himself to walk back and snatch it away.” Over the course of his presidency, Johnson’s staff accumulated a substantial file of doodles by not only the president but also by other administration officials and visitors.

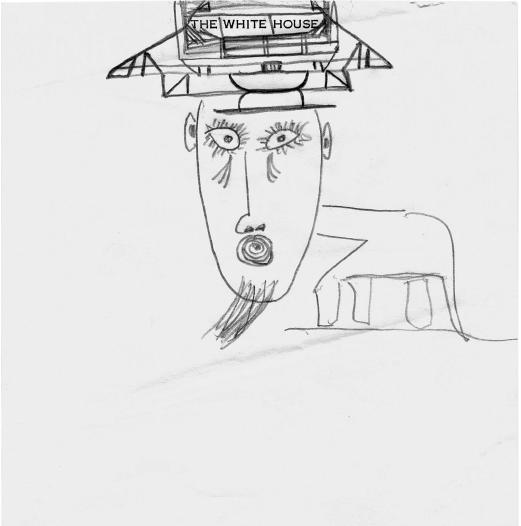

It’s not always clear which doodles were drawn by LBJ and which by others, although many of the president’s have a distinctively aggressive and manic quality, along with a child-like primitivity. The doodle on the opposite page is one of Johnson’s finest, with a devilish cat-like animal, a three-headed character in a dress, and a third figure obliterated by violent scrawls.

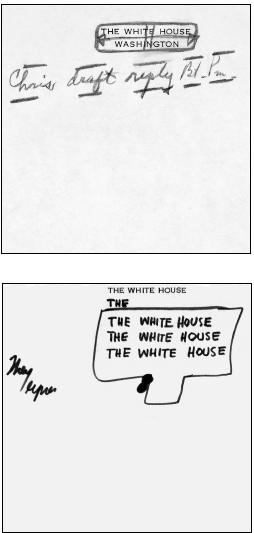

Although many of Johnson’s doodles reflected his explosive personality, others showed a different side of his character, which was coolly measured and systematic. The checkerboard pattern (left) recalls George Washington’s meticulous lines, and the grid (below) shows a similar taste for orderly, predictable rhythms. Despite his overflowing, outsized personality, LBJ could summon tremendous discipline when he wanted to pass a bill—or advance his career.

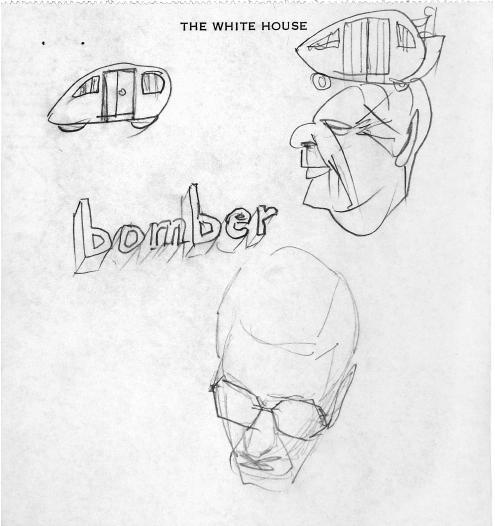

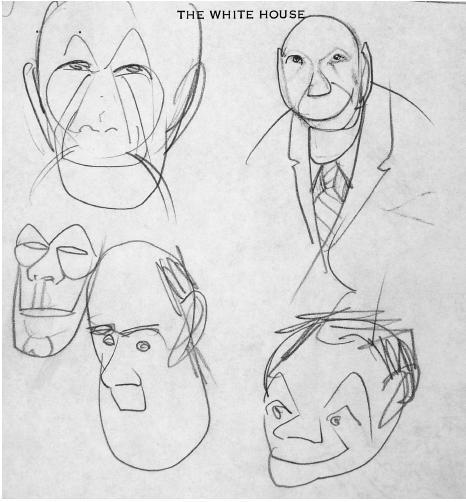

In this doodle, LBJ again shows his strange predilection for drawing figures with three faces. The drawing also reveals his habit of building his doodles around the words “The White House” on his official stationery. On the following pages, Johnson plays on that theme in a variety of ways, turning the name of his residence into a flag, a pagoda, a prison, and other forms.

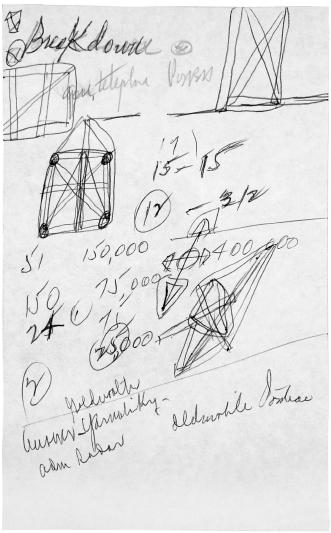

Johnson drew this doodle on August 11, 1964, just a week after the Gulf of Tonkin incident, which led to the escalation of the American military involvement in Vietnam. Clearly, LBJ had much on his mind. His notes include a reference to Barry Goldwater, his rival in the presidential race that year, and also a reminder to “answer [Adam] Yarmolinsky,” an aide to Attorney General Robert Kennedy. An Oldsmobile and a Pontiac make appearances as well.

The word “breakdown” here probably refers to something innocent, such as a breakdown in communication. But it’s hard not to read it and think of the terrible emotional toll Vietnam took on Johnson. No one has suggested that the president literally had a nervous breakdown, but he became increasingly anguished as the quagmire of the war deepened—not only leading to the deaths of many more American boys than he’d ever envisioned, but also constraining Johnson from fulfilling his vision of the Great Society. Richard Goodwin, a Kennedy aide who stayed on the White House staff into the Johnson administration, later wrote that he believed LBJ was suffering at the end from bouts of paranoid delusion—a claim, it should be noted, other Johnson aides vigorously denied.

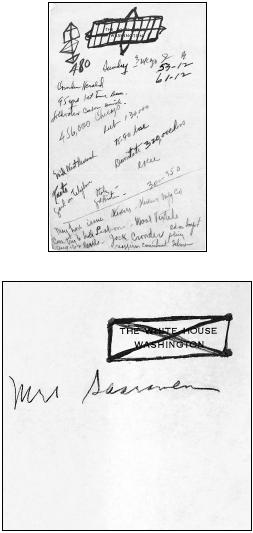

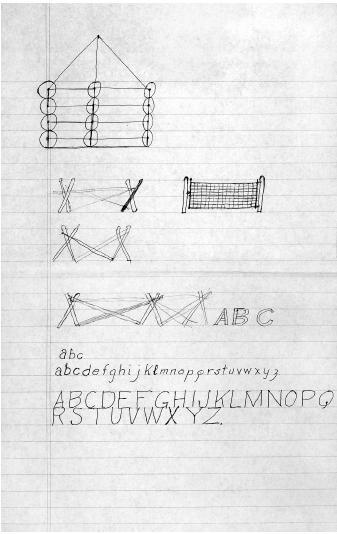

This doodle comes from a meeting LBJ held with union and railroad leaders before an expected strike in April 1964. In addition to drawings of what look like a log cabin and split rail fences (and perhaps a tennis net), Johnson wrote the alphabet, as he was wont to do. Usually, however, LBJ generally didn’t simply write out the alphabet from A to Z but rather repeated certain sequences of letters over and over.

In a different picture he drew, it took him sixty-one letters to get to Z because of all his repetitions and backtracking.

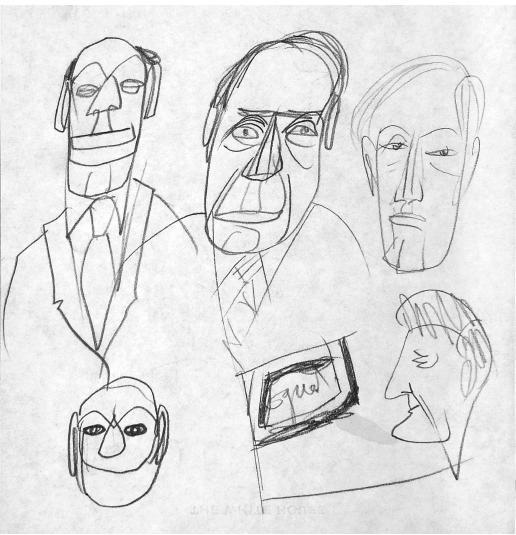

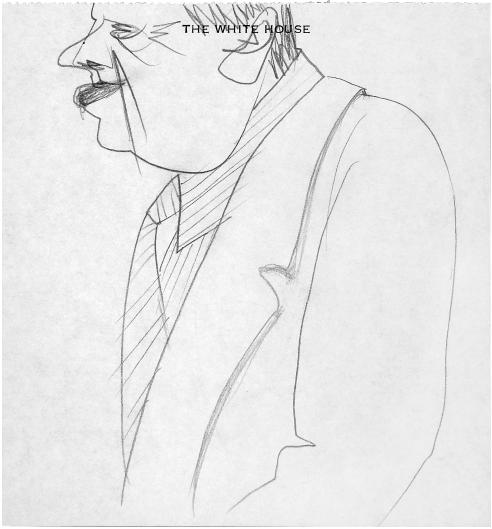

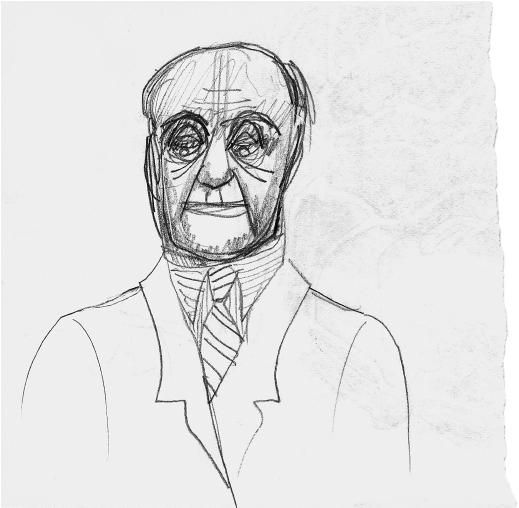

This doodle, and the ones on the next four pages, were made not by Johnson but by an unidentified White House guest over a few days in December 1964 when British Prime Minister Harold Wilson was visiting Washington. The subjects drawn by this mysterious doodler resemble Vice President Hubert Humphrey, Senator Edward M. Kennedy of Massachusetts, and other American and British officials.

Regardless of the artist’s identity, it’s clear that the Johnson White House was a hospitable home for doodlers.

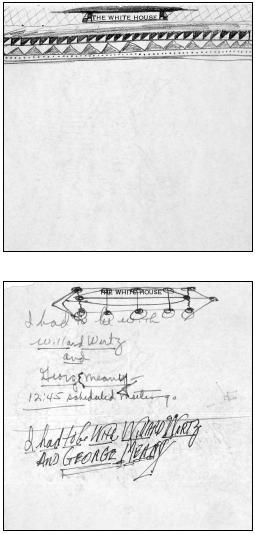

Reflecting the rampant doodling in the Johnson White House, this drawing appears to be a hybrid of two different scribblers’ work. The frieze drawn around “The White House” on the stationery may very well be the president’s handiwork, but the cartoon creature below it is drawn in a different style.