“The True Remedy for the Fugitive Slave Bill is a good revolver, a steady hand, and a determination to shoot down any man attempting to kidnap.”

—Frederick Douglass, 18541

There was no sign of anything special happening when the slave boy Fred Bailey stood up and fought the rawboned Maryland planter they called “Covey the Nigger-breaker.” Negroes had been striking back against the prosaic violence of slavery since the beginning. The nature of that resistance and its impulses are contested today, and these cavils may never be settled. But at the core, the deeds and decisions of earlier generations of slaves, fugitives, and freemen ground Martin Luther King’s twentieth-century debate with Robert Williams and frame the black tradition of arms.

Violence in the freedom struggle resonates differently over time. Political nonviolence so dominates the story of the modern civil-rights movement that it obscures the tradition of individual self-defense. And while the folly of political violence seems plain today, the case against it did not always sway black folk. Indeed, luminaries of the nineteenth-century leadership class advocated organized violent resistance against slavery as a matter of considered policy. And before that, cryptic accounts of early American slavery, evidence abundant individual and organized resistance.

Martin King and Robert Williams debated the boundaries of an established tradition. But the roots of that tradition, like births and deaths and black family trees that fade to dust under slavery, are not fully recorded in the fashion of other important American developments. So the early story, we piece together—some of it from rare accounts by black folk and more of it as remnants from the stories of the conquering class.

Partly this yields unsympathetic renderings of quick, violent outbursts and loosely organized, swiftly quashed revolts—the widely recounted insurrections of Denmark Vesey, Gabriel Prosser, Charles Deslandes, Nat Turner, and an estimated 250 more obscure episodes. In other brief accounts and sterile court records, we see the familiar, unplanned human reflex to meet violence with violence that reflects why philosophers speak of a natural right to self-defense.2

Some scholars argue that early arrivals from Africa were culturally inclined against organized violence and favored individual combat charged with African ritual. Others contend that lingering tribal rivalries and language barriers hindered planning for group resistance. Still others say that organized slave revolts had a clear African base and that it was American-born blacks who adopted practical survival strategies that eschewed suicidal rebellions.

Records of early criminal convictions suggest that direct violence against masters or other whites was more likely from “unseasoned” slaves new to the Americas. “Seasoned” slaves, acclimated to the culture, were more likely to resist surreptitiously. Eighteenth-century prosecutions and executions for arson and poisoning suggest that this was not uncommon.3 Many acts of resistance defy rigid boundaries, demonstrating both a personal fight against the immediate violence of slavery and a political resistance against the slave system. The black tradition of arms grows out of this milieu.4

Fred Bailey’s situation was common. He had been rented out to Edward Covey by his master, Thomas Auld. Bailey was young, just coming into manhood. Some said that the handsome mulatto had been coddled. And Auld perhaps thought that too. A year away with Covey would train him up right.

Covey wrung a living out of the silty loam of Maryland’s eastern shore. He drove Negroes hard. With a nod and a knowing smile, men called him “Nigger-breaker,” in earnest respect for his particular talent and general disposition. Like others of his type, Covey was the slavers’ medicine for young bucks with too much spirit.

Fred Bailey was not the typical problem, though. Relatively speaking, he was soft, his early life spent in the comparative comfort of the Baltimore home of Hugh Auld, Thomas’s brother. It was there, as bonded companion to Hugh and Sophia Auld’s young son Tommy, that Bailey learned to read from the Bible at the knee of the kindly Sophia.

Bailey surely was a slave, presented to Tommy as “his Freddy,” and formally charged with serving and protecting the younger boy. But the work of servile big brother was not taxing and often left Bailey free to roam the streets and docks of Baltimore. Fieldwork under Covey’s lash was a jolting immersion into the more common experience of American Negro slavery.

One steamy afternoon in 1833, the August heat dragged down the tenderfoot. Part of a team of four assigned to threshing, Bailey lagged, stumbled, and then passed out. His job was to carry raw, stalked grain to the thresher. When he stopped working, the threshing stopped. The commotion of threshing was profit. Silence was loss. And Covey was quick to investigate.

Bailey was laid out in a shady spot next to the thresher when Covey approached and demanded explanations. Bailey, in a heat daze, mumbled excuses. Covey figured first to kick him back to work and planted a boot hard in his side. Bailey rose partway, fell back, got another kick, and then another. Crab-walking, attempting to stand, then falling again, Bailey was somewhere between up and down when Covey bashed him in the head with an oak-barrel stave. The blood flowed. And this time Bailey stayed down, resigning himself to dying right there if that was his fate.

The beating was having the opposite effect Covey wanted. He was worn out from giving it, and Bailey was no closer to resuming work. Covey stomped off in disgust. Bailey, splayed out on the ground, bleeding from the head, resolved, if he survived the moment, to flee.

At the first clear chance, Bailey crawled off into the woods, barefoot and bleeding. His destination was St. Michaels, seven miles away. There, he imagined finding relief in the self-interest of Master Thomas. It was fair to think that Auld would object to Covey abusing his valuable property. Bailey might even have thought to prevail on whatever advantage rested in the whispers that Auld was actually his father. It was not an unreasonable hope. Auld had twice rescued Bailey from the fate of a field hand, arranging for soft duty in Baltimore with Hugh, Sophia, and Tommy.

The welcome in St. Michaels was disappointing. Bailey looked how you would expect from a kid who had dropped from heatstroke, taken a beating, and then fled barefoot through seven miles of forest and swamp. But Thomas Auld had little sympathy either for Bailey’s appearance or for his story. Auld knew Covey. Covey was a good man. Whatever had happened, Bailey must have deserved it. And, of course, as a matter of law, there was really nothing to be done. Covey had leased Bailey for a full year. It would be legally, nay, morally wrong to welsh on the bargain.

In another era, biographers, speculating about the blood connection and Auld’s multiple rescues, would claim that there had been something like love binding Fred Bailey and Thomas Auld. Maybe this exaggerates things. But whatever affection there was, Auld’s refusal to intervene with Covey was the end of it for Bailey. Bailey’s later depictions of Auld exhibit only disdain.

Early the next morning, ordered to return to Covey or be whipped and returned by force, Fred Bailey reversed course and trudged seven miles back to the scene of his escape. Climbing over the rail fence into the front pasture, he encountered Covey charging toward him, bullwhip in hand. Whatever impulse had moved Bailey to run off, Covey intended to beat out of him. But he had to catch him first.

Bailey fled to the high corn and crawled down low. Covey lost the scent. Exhausted and hungry, Bailey spent the day in the woods, at the edge of the fields, deciding whether to run back to St. Michaels to a whipping, surrender to Covey for a whipping, or stay in the woods and starve.

That night, Bailey roamed the fields and woodlots until he came to the little cabin of Sandy Jenkins, who is recorded either as a free black or a slave who enjoyed a degree of independence, living in his own place with a free black woman. Sandy let Bailey wash up and shared his simple dinner as they talked about what to do.

Sandy was at least a generation older than Bailey. He had longer experience with the violence of slavery. He also was the keeper of secrets. While Sandy’s wife cleaned up, man and boy walked out into the darkness. Sandy said Bailey must surrender to Covey. He also promised Bailey something that seems fanciful today, but less so then.

Deep into the woods, where the light from the cabin fire was lost, Sandy worked under the moonglow, scratching and probing. Then, on his knees, clawing into the black loam, he tugged up a root from the breathing forest.

Years later, after he had escaped from slavery, thrown off the name Bailey, and become what the New York Times called the “foremost man of his race,” Frederick Douglass recounted how wise old Sandy had bestowed on him “a certain root, which, if I would take some of it with me, carrying it always on my right side, would render it impossible for Mr. Covey, or any other white man, to whip me.”

Looking back, it is pleasing to speculate about the magic of the root and the forces of destiny that were taking hold. What we can say for sure is that the next encounters between the “Nigger-breaker” and the nascent abolitionist, orator, writer, publisher, and freedom-movement pioneer Frederick Douglass were to be profoundly different from what had passed before.

Away for several days now, with only a brief appearance and a retreat into the corn, Douglass returned to the Covey farm early on the Sunday, buoyed gingerly by the promise of Sandy’s root magic. Walking toward the main house, he spied Covey, dressed for church. His temperament reflecting his destination, Covey acknowledged Douglass calmly and gave him instructions for a bit of work that would not take long. Douglass finished the work and spent the remainder of the day contemplating the magic of the root, the wonder of the Sabbath, and the other mysteries that had pacified Covey since their last meeting.

Like countless Mondays before and since, the warmth and charity of the Sabbath had faded by the next morning. It was not yet daylight when Douglass was lured into the stable with instructions to tend the horses. He was climbing down from the loft when Covey entered with a rope, lassoed him, and yanked him to the floor. Douglass later recounted it this way:

Covey seemed now to think he had me, and could do what he pleased; but at this moment—from whence came the spirit I don’t know—I resolved to fight; and suiting my action to the resolution, I seized Covey hard by the throat; and as I did so, I rose. He held on to me, and I to him. My resistance was so entirely unexpected, that Covey seemed taken all aback. He trembled like a leaf. This gave me assurance, and I held him uneasy, causing the blood to run where I touched him with the ends of my fingers.

Covey called out to his cousin, Hughes, for help. Hughes waded in just long enough to get a strong kick in the ribs from Douglass and was out of the fight. Covey went for a stick, but Douglass intercepted him and flung him by the neck back to the ground. Covey yelled for help to Bill, another rented slave. Bill objected that he was a valuable working man whose master would not want busted up.

From there, it was just Douglass and Covey, fighting like men until they were spent. And like most episodes of violence, the aftermath was crucial. Here, the odds shifted sharply against Douglass. Violence against whites, even in self-defense, was a hazardous bet for slaves. With the legal status of mules, they were treated accordingly by American courts. And it is a compelling intuition that, except for self-defense in the course of a successful escape, violence against whites would more likely just delay injury or death than prevent it.5

Douglass himself wondered why Covey did not have him taken to the constable and “whipped for the crime of raising my hand against a white man in defence of myself.” The answer, he thought, was that Covey had a reputation as a breaker of Negroes, and his brand would suffer if he were forced to send a defiant sixteen-year-old to the public whipping post.

Whether it was this or something grander and preordained that accounted for Covey’s reticence, is impossible to know. What we do know is that Douglass was transformed. Filthy and sweating, Covey dragged himself up out of the mud and admonished that he “would not have whipped him half so much” if Fred had not resisted. Douglass saw it differently. “He had not whipped me at all. I considered him as getting entirely the worst end of the bargain; for he had drawn no blood from me, but I had from him.”

For Douglass this was the turning point in his life as a slave that kindled his quest for freedom, and marked his passage into manhood. “I was nothing before. I was a man now. . . . And determined to be a FREEMAN! . . . I resolved that, however long I might remain a slave in form, the day had passed forever when I could be a slave in fact. I did not hesitate to let it be known of me, that the white man who expected to succeed in whipping, must also succeed in killing me.”6

Frederick Douglass was far from the first to fight. And given the danger that even vaguely suspected aggression might trigger severe punishment, it is evidence of the power of the self-defense impulse that slaves fought back with some frequency. A study of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century criminal convictions shows that violence against masters lead the next closest category of slave crimes (theft) by a factor of three.7

For episodes that made it to the courts, slave self-defenders typically met quick, severe punishment. This is illustrated in early Missouri court records, where the aftermath of slave violence was predictable. Punishment was swift in 1818 for a St. Louis slave who stabbed and killed his owner in order to avoid a whipping. He was tried, in a fashion, and quickly hanged. It happened again in 1828, when John Tanner’s slave, Moses, somehow acquired a gun and shot and killed Tanner. Missouri courts were unsympathetic to Moses’s claim that Tanner had “acted disgracefully” toward Moses’s wife. Denied the prerogatives of honor that might be extended to a white man, Moses was summarily tried and hanged.

The scenario repeats in 1859, in the town of Buchanan, where a young slave who had been sold off to a slave trader managed to conceal a pistol, shoot the trader, and escape. He was apprehended and swiftly hanged. It happened again in 1863, when a slave named Henry shot his master after being threatened with a whipping. The shooting occurred in July. Henry was hanged by the end of August.

In another variation on the theme, a free Negro in St. Louis shot and killed a deputy and wounded another in an attempt to keep one of his neighbors from being carted back to slavery. The effort failed on all counts. The fugitive was hauled off in a yoke, and the free black Samaritan was burned at the stake by a mob.

Negro violence yielded slightly better results in 1843 in Boone County, Missouri. There, a group of five slaves plotted to kill their master, who had threatened to whip the lot of them. With axes and the advantage of numbers, they hacked Hiram Beasley to death and ran off. Two of them were apprehended and hanged, but the others escaped.8

In an exceptional North Carolina case, State v. Negro Will, a slave sentenced to death for killing his overseer had his conviction reduced to manslaughter by the North Carolina Supreme Court. For the time and place, it was an extraordinary recognition of a Negro’s basic self-defense interest. Will killed the overseer in a conflict over a garden tool. His title challenged, Will decided no one would have the thing. He snapped the handle and stomped off. Inflamed by this defiance, the overseer, Baxter, chased Will down and emptied his revolver at him. When Baxter came in close, Will sprang forward and killed him with a knife. Will’s owner was convinced it was self-defense and paid two leading North Carolina lawyers $1,000, approximately Will’s cash value, to represent him.

Negro Will was an exceptional case. More emblematic of the times is the North Carolina court’s far harsher assessment in State v. John Mann, which overturned the conviction of a slaver who shot his Negro girl as she attempted to flee. The case underscored the basic principle that masters were not criminally liable for violence against their slaves, bolstering the intuition that slave self-defense was more of a desperate last act than a viable survival strategy.9

In this sort of environment, it is hard to say that Douglass’s fight with Covey and countless other episodes of slave resistance were fully rational acts. But how then to classify them? It is common across history to celebrate doomed fights against impossible odds as the essence of heroism. But those fighters generally have champions among poets and storytellers in cultures hungry for such heroes. The black tradition of arms will yield many folk who fought desperately against long odds. But query whether there is space in our culture to think about them as anything more than victims.

For Frederick Douglass, looking out from the middle of the nineteenth century, there was slim reason to believe that Negro resistance in the fight for freedom would ever be celebrated within the American story. Even after he had achieved fame, some fortune, and international acclaim, Douglass was still stigmatized by the United States Supreme Court as part of a class who held no rights that the white man was bound to respect.10

Despite that blighted logic, or perhaps because of it, Douglass’s rise from less than nothing is actually the most American of stories. At age twenty, or nineteen, depending on whether we credit Douglass’s guess or biographers’ research, he stole away from slavery out of Baltimore, disguised as a sailor. He would become one of America’s most formidable abolitionists, so talented as an orator and writer that incredulous racists would charge that his claim of escaping from slavery was a fraud.11

Douglass was one of the earliest and most prominent blacks to wrestle publicly with the role of violence in the freedom struggle. Even in his early career, still under the sway of pacifist abolitionists who “discovered” and advanced him, Douglass had difficulty translating pacifist appeals to the conscience of slavers into something that resonated for Negroes.

The terror of slavery and the fugitive slave laws ultimately pushed Douglass to advocate not just armed self-defense but overt political violence and slave insurrection. By the middle of the nineteenth century, having broken away from William Lloyd Garrison’s pacifist abolitionists, Douglass offered a bold prescription for the man-hunters who were licensed by the final and most damnable of the fugitive slave laws. Speaking to both fugitives and freemen, Douglass advocated, “A good revolver, a steady hand and a determination to shoot down any man attempting to kidnap. . . . Every slave hunter who meets a bloody death in his infernal business is an argument in favor of the manhood of our race.”12

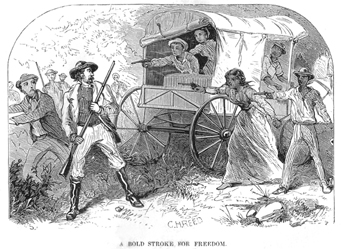

Fig. 2.1. Fighting the Mob in Indiana, an artist’s rendering of Frederick Douglass fighting a proslavery mob (1843). (Courtesy of Documenting the American South, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Libraries.)

In some sense, it was inevitable that Douglass’s advice spilled over from self-defense into political violence. Putting aside debates of higher law, slave hunters were not criminals. Their nefarious craft was explicitly authorized by the Constitution of the United States, enshrined in Article IV, Section 2, and embellished subsequently by statute, in the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793. This was still deficient, said slavers, because it was weak on federal enforcement and permitted free-state laws that interfered with slave recapture and exposed man-hunters to assault and kidnapping charges.

The final and harshest fugitive slave law was rendered by the Compromise of 1850, which aimed to ease the tensions over whether new states would enter the union slave or free. With the nation pulsing under the fever for westward expansion, the Compromise of 1850 brought California into the union as a free state, let voters in other new states decide about slavery for themselves, and put federal law enforcement squarely behind the recapture of slave property.

In later generations, black leaders would assess political violence from inside the fence. Nominally citizens, nominally right-bearers, and ultimately outnumbered, blacks would largely reject violence as a tool for achieving political goals. The better bet was to shame America into fulfilling the promise of its founding ideals.

But under slavery, the calculation was different. Negroes were excluded entirely from the system, branded as an inferior cast with no basic human rights, let alone political ones. So the appeal of political violence, desperate and doomed as it might be, is understandable. There was little reason to worry about maintaining some strategic boundary between political violence and self-defense.

For much of his activism, this was Douglass’s calculation. And for many Negroes, it had long been so. Many fugitives were pressed either to fight or to return to bondage. Whether you called it self-defense or political violence mattered little. And starting early on, fugitive and freeman, these Negroes fought.

From the beginning, free blacks were a threat to slave culture and an important resource for fugitives. Associations of free blacks date to the beginning of the American state. Some were formal, like the Philadelphia Free African Society, formed in 1787 as white America framed its Constitution. Other groups were less organized and more thinly recorded, often just clusters of caring neighbors, clear-eyed about the utility and morality of violent self-defense. In 1804, one of these groups in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, interdicted a slave catcher, stripped him naked, “and beat him soundly with hickory switches.” In most cases, though, folk were more effectively armed.

In 1806, near Dayton, Ohio, a gun was Ned Page’s most important possession. Ned and his wife Lucy were technically free people, brought from Kentucky under circumstances that extinguished claims to them as property. So said Ohio. But words in law books often don’t translate into reality. If things happened fast enough, decisive action would trump the parchment barriers of Ohio law.

The Pages were laid over in a makeshift tavern when two armed men entered intent on hauling them back south in chains. Ned Page pulled a pistol from his pack, squared up his sights and threatened to kill rather than be taken. A clutch of friends surrounded him in support. The slave catchers were apprehended and charged with breach of the peace.

In 1810, armed black men rode to the rescue in Jefferson, Ohio, after an informer set slave catchers onto a family of fugitives. The capture was easy. The return was not. The kidnappers had the family yoked and headed south when they were intercepted by a group of fifteen to twenty “colored men armed with guns pistols and other weapons.” The two sides maneuvered to a standoff and the Southerners agreed to the offer of a white attorney to present their claim to the authorities. The local magistrate rejected the slavers’ claims and released the Negroes. In a final insult, the slave hunters were charged with assault. They posted bail and rode off, forfeiting their bond.

Many early episodes where fugitives got their hands on guns shifted quickly into primitive combat. This accords with the firearms technology of the time. When Frederick Douglass advised blacks to acquire a good revolver, practical applications of that multishot technology were only a few decades old, made viable by Sam Colt’s percussion-cap revolver in 1836 and Horace Smith and Daniel Wesson’s more efficient cartridge system in 1851. Before that, armed self-defense generally involved single-shot or, more rarely, multi-barrel guns, sparked by flintlocks or percussion caps. Except where people had multiple guns, additional fighting meant contact weapons. John Reid’s resistance in 1820 is illustrative.

Reid was a fugitive slave living in Kennett Township, Pennsylvania. He was sitting by the fire in his cabin when armed slave catchers began breaking through his door. Reid grabbed his gun, and shouted, “It is life for life!” The first man through the door was Samuel Griffith, Reid’s owner come to claim him. Reid shot Griffith dead. The second man through was Reid’s former overseer, Peter Shipley. His firearm spent, Reid killed Shipley with a club strike to the head. Reid was charged with murder. But the antislavery sentiment in the area was such that the jury acquitted him on the murder of Griffith and convicted him of a lesser charge in the death of Shipley.13

So where did nineteenth-century Negroes get their guns? The answer varies substantially by place. Free blacks and fugitives who escaped to the North could acquire guns through a variety of legitimate channels, constrained mainly by their resources. But Southern blacks had to navigate the first generation of American arms-control laws, explicitly racist statutes starting as early as Virginia’s 1680 law, barring clubs, guns, or swords to both slaves and free blacks.

It is a fair intuition that that slaves obtained guns mainly by theft. But there are indications that some slaves were actually entrusted with guns by their masters. Slave-state gun-control laws actually reflect this. An eighteenth-century Maryland law commanded that “no Negro or other slave, within this province, shall be permitted to carry any gun or any other offensive weapon, from off their Masters land, without license from their said master.” A similar Georgia law declared that no slave could possess a firearm except where accompanied by “a white person of at least 16 years old, or while defending crops from birds.”14

In some cases, slave access to firearms entirely defies modern intuitions. Court records from prewar Vicksburg, Mississippi, show that some slaves had direct access to the market for firearms, alcohol, and other contraband, through trading with white merchants who were periodically arrested and prosecuted for selling to blacks.

One of the exacerbating factors in this illegal trade was the practical limit on the kind of oversight that masters could exercise over their slaves. Some bondsmen found relative freedom in the unavoidable circumstances of their work. Many of the wagon and carriage drivers around Vicksburg enjoyed a great deal of autonomy because it was impractical to supervise them as they chased fares and hauled cargo.

Slave masters often found it simply more profitable to assign Negroes to unsupervised tasks or to allow trusted slaves to hire themselves out or even run their own businesses. One planter in prewar Vicksburg, Mississippi, actually bragged that his boys were so enterprising and such prodigious savers, that he had borrowed money from them himself. One slave couple was reported to have accumulated thousands of dollars’ worth of property, including two tracts of land held in trust for them by a white attorney. Another slave named William Hitch, who lived and worked in town away from his master, commented that he had been essentially “free since he was a boy” because his owner allowed him total control in hiring out his time.

Some slaves from this class used their accumulated capital to buy their freedom. Others remained in place, building resources, and in some instances, aided by their owners, passed their assets on to heirs. In some places this dynamic gave rise to the “nominal slave,” whose relative freedom was alternately a blessing and a curse for whites.

Many whites considered the freer rein given to nominal slaves a hazard. In 1859, Vicksburg papers editorialized that the “class of Negroes now among us who are pretended to be owned by a white men [are] a pest and annoyance of the town.” These “quasi-slaves” were derided as “vicious and insolent . . . keepers of half-wild horses, cattle and dogs.”

This often-unsupervised slave culture facilitated trading of both alcohol and guns. Court records in Warren County, Mississippi, reveal more than one hundred cases alleging illegal trading by whites with slaves. Many of these are sales of alcohol. But some cases, like the prosecution of Christian Fleckenstein, provide rich evidence about illicit trading of firearms.

Fleckenstein was a threadbare merchant and widely rumored seller of contraband to slaves. Suggesting the division of interests between slavers and the merchant class, one local slave owner, fed up with Fleckenstein’s illicit trade, set a trap to build a case against him. The planter sent one of his slaves into Fleckenstein’s store with three dollars and clear instructions. The slave returned with a bundle containing liquor and a gun.

Fleckenstein was arrested and tried. The litigation is an interesting insight into the slave world and the difficulty owners had in simultaneously controlling their slaves and extracting their full economic value. The court charged the jury that Fleckenstein should be found guilty unless he could produce a note giving the slave permission from his master to purchase the gun and the alcohol. The court was willing to acknowledge that a master might plausibly send a slave on an errand to buy either item.

Fleckenstein, of course, had no such proof and was convicted. On appeal, his conviction was reversed on technical deficiencies in the indictment. Fleckenstein continued trading with slaves and evidently was joined by a handful of other “disreputable groceries.” Over time, the low trade generated fat profits that allowed the disreputable grocers to build sturdy brick homes.

Another incident in Vicksburg suggests that blacks had access to firearms through theft or through a loose trading culture well before the sting operation on Christian Fleckenstein. In 1835, white Vicksburgers pursued a private remedy against the abundant gambling, drinking, and prostitution in “the Kangaroo,” a local haven for slaves, nominal slaves, and free blacks. After heated conversations and the passing of resolutions, a group representing the good people of the town marched in military formation to one of the hangouts in the Kangaroo. The show of force was repelled when the blacks launched a volley of gunfire that killed one man. Whites sent for reinforcements and ultimately prevailed, apprehending and hanging five occupants of the house.

There is no explicit detail on where the Negroes of the Kangaroo got their guns. But the indications that many of them were armed suggests a level of access to firearms beyond the random opportunity to steal one. The “nominal” slave class, with assets and broad trading opportunities, probably had access to guns and would have been a source of guns for Negroes with more limited opportunities.15

Another hint about the nature of slaves’ access to firearms appears at the end of the Civil War in an 1865 debate of a white vigilance committee about disarming the freedmen in and around Somerton, South Carolina. In what seems to be an unusual objection for the time and place, Lauren Manning, a lowland planter, opposed disarming newly minted freedman, arguing that “some of his slaves carried weapons for the protection of the plantation before the war, and now these men had been made free and therefore had a right to carry arms.”16 Manning’s objection was overruled, and the vigilance committee set out with some vigor to disarm local Negroes. But Manning’s statement that his slaves had carried firearms confirms that slaves sometimes accessed guns in ways that may seem surprising today.

Still, the intuition that theft accounted for a substantial portion of slave access to firearms remains sound. When the slave couple Loveless and Pink ran off with their three children from Leon County, Florida, in the mid-1830s, they stole master Cornelius DeVane’s shotgun and all the provisions they could carry.17 Fugitive slave Henry Bibb not only stole his master’s gun but later wrote a book about his adventures that describes the gun theft this way: “For ill treatment we concluded to take a tramp together. . . . Before we started I managed to get hold of a suit of clothes the Deacon possessed, with his gun, ammunition and bowie knife.”18

Theft also was the source of the guns used by two young runaways who were pursued by patrollers on horseback. When the horsemen closed on them, the slave boys opened fire with a brace of pistols, ending the pursuit and escaping. And on the Manigault plantation in coastal Georgia, overseers confirmed that slaves were stealing and hoarding ammunition when they discovered a cache of shot and powder hidden by a slave named Ishmael who confessed his plans to run off.19

Other episodes leave us wondering more intently about the source of slave armament. Cryptic reports of armed bands of escapees suggest multiple thefts or stockpiling in preparation for escape. A mass slave escape from southern Maryland in 1845 is indicative. The fugitives, numbering between seventy and eighty, were led by a free Negro named Bill Wheeler. On a stifling hot July evening, the unsupervised men snuck off and then assembled as a body, marching in discipline, carrying pistols, blades, and farm tools improvised into weapons. With a semblance of military planning that defies intuitions of spontaneous escapes, the group separated into two companies and proceeded along alternate routes. Eventually, the larger group was corralled outside Rockville, Maryland. The blacks closed ranks and exchanged gunfire with their pursuers. Several Negroes were wounded, two of them stood trial, and one was executed.

A similar incident occurred the same year when ten slaves escaped from Hagerstown, Maryland. On their way to Pennsylvania, they confronted an equal-sized white posse. As the pursers closed in, the slaves “drew themselves up in battle order” and attacked with pistols and tomahawks. Eight of the fugitives managed to escape, leaving behind two of their own dead and several wounded whites.20

In 1848, forty-seven blacks armed with guns and knives fled Kentucky bound for Ohio. Before reaching the Ohio River, they were surrounded by three hundred armed whites. The fugitives stood and fought in two separate skirmishes but ultimately surrendered. Many of the escapees were put on trial for sedition and insurrection. Three were convicted and hanged. Several others were saved by their masters, on the argument that the benefit of more hangings was less than the value of the men as property. Armed fugitives had more success in 1855 when a group of six runaways from Virginia deployed pistols and knives to fight off bounty hunters who detained them in Maryland. Here the full group managed to get away.21

The escape story of Reverend Elijah P. Marrs is particularly instructive, in that it contains an explicit admission of gun theft. Marrs was born into slavery in Shelby County, Kentucky, in 1840. He rose to become a revered clergyman, educator, and standout in Reconstruction-era politics. During the early stages of the Civil War, Marrs risked retribution at the hands of Shelby County rebels for reading and writing letters for local slaves. As the war progressed, the danger mounted for the “Shelby County Negro clerk,” and he soon decided to run off to the Union Army.

In the late summer of 1864, Marrs organized a group of twenty-seven slaves who set out for Union lines. Confirming the surmise that theft was a source of guns for slaves, Marrs reports that his group was “armed with . . . war clubs and one old rusty pistol, the property of the captain.”22

It is not clear whether Elijah Marrs’s group actually fired their solitary gun or whether they gained some advantage by brandishing it. Researchers say that brandishing guns without firing them is the most common form of armed self-defense today.23 Although it is impossible to know how often slaves benefited from brandishing guns, if the modern trend applied, those episodes would far exceed incidents of actual gunfire, and those nonshooting defensive gun uses would likely go unrecorded.

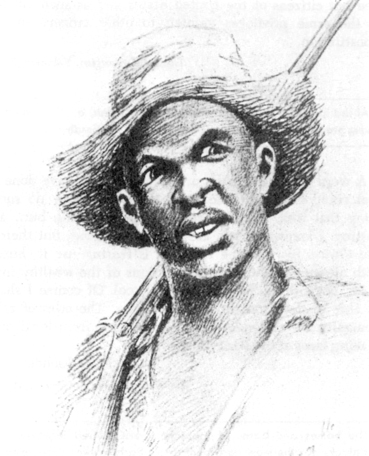

Some evidence of nonshooting, defensive gun uses under slavery survives because it involved famous Negroes. Consider the long practice of Harriet Tubman, storied conductor of the Underground Railroad, who reportedly guided more than seventy slaves out of bondage. There are no accounts of Tubman exchanging gunfire with slave catchers. But she is widely reported and depicted carrying a rifle, a musket, or a pistol. Some modern researchers, queasy about the notion of a gun-toting Tubman, argue that her guns were unloaded—a theory hard to square with Tubman’s scouting for the Union Army.

Tubman was not the only guide on the Underground Railroad to carry a gun. Lesser-known black abolitionist John P. Parker not only carried guns in his forays south, but also claimed to have used them in what he described as “warfare” with slaveholders. By the middle of the nineteenth century, Parker had settled in Ripley, Ohio, where he harbored scores of fugitives, brawled, brandished guns against slave-hunting gangs, and “never thought of going uptown without a pistol in my pocket, a knife in my belt, and a blackjack handy.” One account credits Parker with making Ripley “as important an escape route as any in the nation.” Parker was clearly not the only armed conductor in the vicinity of Ripley. Fugitive slave Francis Fredric recounted escaping through Ripley, where he was “well-guarded by eight or ten young members with revolvers.”24

Fig. 2.2. Harriet Tubman, conductor of the Underground Railroad. (Woodcut ca. 1865.)

In the mid-1850s, Parker aided in a daring raid into Kentucky, under the planning of white abolitionist minister John Rankin. A group of runaways was stranded on the riverbank in slave territory. Parker reports that Rankin asked him to come to their typical meeting place and bring every gun he owned. Parker wrote later,

I had been told to bring all my firearms, which I did, including an old musket. I knew something serious was up, because this was the first time I’d ever been called on to come, armed with anything but small arms. . . . I can still see the pale face of Reverend Rankin as he sat in the center of this council of war, arguing for his plan of rescue. . . . To go heavily armed . . . and take the group forcibly from anyone who got in the way.

That night, a squad of seven men spread across three boats and armed with everything they had, landed in slave territory and retrieved the shivering clutch of runaways.25 The scene repeats in the story of John Henry Hill, who escaped to and continued to agitate from Canada. Hill reports engaging in a gunfight with his master before fleeing Richmond, Virginia, armed with “a brace of Pistels.”26

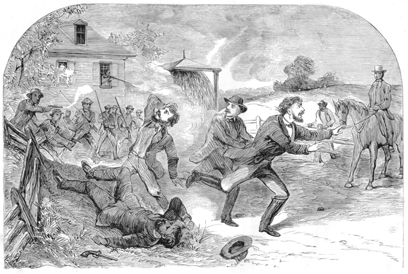

William Still, a freeborn Negro, hailed as the “father of the Underground Railroad,” produced a remarkably textured eight-hundred-page account of fugitive slave escapes, including episodes that fulfill the longing for the detail that is missing in so many accounts of fugitive slaves wielding guns. Working through the Philadelphia Anti-Slavery Society, Still aided hundreds of escaping slaves and eventually began interviewing them and recording their stories. One of the most iconic images of Negroes with guns during slavery appears in Still’s account of the escape of Barnaby Grigby, Mary Elizabeth Grigby, Frank Wanzer, and Emily Foster. They were fugitives from Virginia who stole their master’s “best horses and carriage” and fled north on Christmas Eve 1855. They made it as far as Maryland without incident. Then, as they entered the Cheat River Valley, a group of “six white men and a boy” thought them suspicious, perhaps the subjects of a reward, and aimed to apprehend them. Still records their story this way:

The fugitives verily believing that the time had arrived for the practical use of their pistols and dirks, pulled them out of their concealment—the young women as well as the young men—and declared they would not be taken! One of the white men raised his gun, pointing the muzzle directly towards one of the young women, with the threat that he would “shoot” etc. “Shoot! Shoot! Shoot!” she exclaimed, with a double barreled pistol in one hand and a long dirk knife in the others, utterly unterrified and fully ready for a death struggle. The male leader of the fugitives by this time had “pulled back the hammers” of his “pistols,” and was about to fire! Their adversaries seeing the weapons, and the unflinching determination on their part of the runaways to stand their ground, “spill blood, kill, or die,” rather than be “taken” very prudently “sidled over to the other side of the road” leaving at least four of the victims to travel on their way.27

The worry about the veracity of such oral accounts is diminished by a corresponding newspaper report that “Six slaves . . . from Virginia came to Hoods Mill . . . and some eight or ten persons gathered round to arrest them; but the Negroes drawing revolvers and bowie knives, kept their assailants at bay, until five of the party succeeded in escaping. . . . The last one . . . was fired at, the load taking effect in the small of the back [and was captured]. He ran away with the others the [next] evening.”28

Fig. 2.3. Fugitives defy slave catchers, from William Still’s account of the 1855 Barnaby Grigby escape. (From William Still’s The Underground Railroad [Philadelphia: Porter & Coats, 1872], p. 125. Courtesy of the House Divided Project at Dickinson College.)

Equally prominent in William Still’s account of slave escapes is the Conflict in the Barn, an image depicting Robert Jackson and his little band of fugitives with guns fighting for their freedom and their lives against a band of border-country slave catchers. Jackson was a fugitive from Virginia, traveling under the alias of Wesley Harris. He had run off after fighting with his overseer, who attempted to whip him for some trifle. Jackson resisted, grabbed the whip, and gave the white man a taste of his own lash. When Jackson’s master heard about it, he decided to sell off Jackson at the next offense.

The mistress of the house had embraced Jackson as a favorite and warned him of her husband’s plans. When Jackson learned that another slave—a fellow named Matterson—and his two brothers, were planning to run off, he conspired to go with them. On the next dark moon, they struck out. It took them two days to reach Maryland. A friendly Negro there warned them of slave catchers scouring the border and advised them to hide. They headed to the countryside and took shelter in the barn of an ostensibly friendly white farmer who “talked like a Quaker,” and promised to help them travel northward to Gettysburg.

Something about the Good Samaritan did not sit right with Jackson, and that sixth sense was a sound barometer. In the morning, eight armed men including a constable descended on the barn, asking questions, demanding to see travel passes, and determined to take the Negroes to the magistrate. Jackson warned, “if they took me they would have to take me dead or crippled.” Then one of Jackson’s companions spied the farmer who had betrayed them and “shot him, badly wounding him.” The constable seized Jackson by the collar, and Jackson responded with pistol fire. He recounted later:

I at once shot him with my pistol, but in consequence of his throwing up his arm, which hit mine I fired, the effect of the load of my pistol was much turned aside; his face, however, was badly burned besides his shoulder being wounded. I again fired on the pursuers, but do not know whether I hit anybody or not. I then drew a sword I had brought with me, and was about cutting my way to the door, when I was shot by one of the men, receiving the entire contents of one load of a double barreled gun in my left arm.

With the help of the Philadelphia Anti-Slavery Society, Jackson survived his wounds. William Still reports that the committee “procured good medical attention and offered the fugitive time for recuperation. . . . And sent him on his way [to Canada] greatly improved in health and strong in the faith that he who would be free, himself must strike the blow.”29

Fig. 2.4. An artist’s rendering from William Still’s account of fugitive slave Robert Jackson’s 1853 fight for freedom. (From William Still’s The Underground Railroad [Philadelphia: Porter & Coats, 1872], p. 50. Courtesy of the House Divided Project at Dickinson College.)

Certainly many acts of resistance did not involve firearms. Sometimes the fugitive himself was the main weapon. In Fairfax, Virginia, for example, two slaves were sentenced to death for a barehanded assault on slave patrollers. The record is richer surrounding the 1844 abduction of “Big Ben” Jones from Bucks County, Pennsylvania. Jones was literally a giant, nearly seven feet tall and correspondingly strong. Jones had escaped from Maryland almost fifteen years earlier. Undeterred by time, his master and four accomplices found Jones in a forest clearing, splitting logs. They approached with pistols and bludgeons and demanded his surrender. Jones feigned submission but then with fists, feet, and his ax, laid into his abductors, taking down two of them before he was overcome. Finally beaten into submission, Jones was hauled into the back of the carriage that could be tracked, said witnesses, by the stream of blood dripping from the floorboards.30 We are left just to wonder whether a gun would have made a difference.

Many Negroes were better prepared than Big Ben Jones, and their reported acts of armed resistance meant that the exhortations of abolitionists like Frederick Douglass were no empty rhetoric. Douglass was less a policy advocate than a reporter of the facts on the ground. In a published speech in 1857, Douglass celebrated recent acts of armed self-defense:

The fugitive Horace at Mechanicsburg, Ohio, the other day, who taught the slave catchers from Kentucky that it was safer to arrest white men than to arrest him, did a most excellent service to our cause. Parker and his noble band of fifteen at Christiana, who defended themselves from kidnappers with prayers and pistols, are entitled to the honor of making the first successful resistance to the Fugitive Slave Bill. But for that resistance, and the rescue of Jerry and Shadrack, the man-hunters would have hunted our hills and valleys, here—with the same freedom with which they now hunt their own dismal swamps.31

It was not just Douglass who championed violent resistance against the fugitive slave law. In 1846, white abolitionist congressman Joshua Giddings of Ohio gave a speech on the floor of the House of Representatives, advocating distribution of arms to fugitive slaves. Giddings saw resistance to slavery as fully within the boundaries of self-defense, declaring, “If a slave killed his master in a struggle to prevent his arrest in Ohio, he would be justified in the eyes of the law and I would call him a good fellow.” Untroubled by the implications, Ohio senator Thomas Morris cast resistance to slave catchers as the ultimate political violence, declaring that the kidnapping of blacks by slave catchers was “an act of war.”

The technical legal claims here are intriguing. The Fugitive Slave Clause in the Constitution plainly recognized slave catchers’ rights through the euphemism that “person[s] held to service or labor” had to be “delivered up” to their masters. This constitutional provision and its 1793 statutory embellishment had no enforcement mechanism, and many free-state laws defied slave catchers. Pennsylvania, for example, made slave catching a crime and indicted man-hunters who chased quarry into the Keystone State. Under this sort of state law, which underscored the violence inherent in the slave catcher’s craft, resistance using deadly force seems fairly within the boundaries of self-defense.

Even with passage of the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act, which put federal authority explicitly behind the claims of slave catchers who ventured into free states, black fugitives and some radical white abolitionists remained untroubled by any theoretical weakness in their stance of righteous violence. This sentiment is evident in an editorial from the Pittsburgh Gazette, which responded to the 1850 law advising blacks “to arm themselves and fight for freedom if need be, but not to run away.”32

Although most slaves did not escape, it is a testament to the spirit and grit of those who did that the storied Henry Clay of Kentucky stomped to the floor of the United States Senate in 1849 to rant that “it posed insecurity to life itself for slave-owners to cross the Ohio River to recover fugitives.” That same year, decrying abolitionist agitation and fugitive resistance, John C. Calhoun agonized that “citizens of the South in their attempt to recover their slaves now meet resistance in every form.” A constituent complained to Calhoun that Pennsylvania’s antikidnapping law made slave property insecure and that rumor of the law had drawn slaves to escape from the upper south in gangs.33

During this same period, there was a great deal of abolitionist agitation directly on the question of arms for self-defense. As early as 1838, the abolitionist paper the Liberator, decried state laws that deprived free Negroes of the basic rights of citizens like suffrage, assembly, and the “right to bear arms.”34

After the Compromise of 1850, the pacifist voices that had dominated commentary in the Liberator were challenged by more aggressive types who advanced the constitutional right to keep and bear arms not merely as an incident of citizenship, but also in practical terms, as a response to slave catchers. In 1851, abolitionist firebrand Lysander Spooner connected higher constitutional principle to the practical security interests of fugitive slaves, declaring:

The Constitution contemplates no such submission, on the part of the people, to the usurpations of the government, or to the lawless violence of its officers. On the contrary, it provides that “the right of the people to keep and bear arms shall not be infringed.” This constitutional security for the right to keep and bear arms implies the right to use them—as much as a constitutional security for the right to buy and keep food would have implied the right to eat it. The Constitution, therefore, takes it for granted that, as the people have the right, they will also have the sense to use arms, whenever the necessity of the case justifies it.35

In 1853, the New England Antislavery Convention pressed the finer technical point of precisely how the Constitution guaranteed fugitive slaves a right to arms. Arguing that the word persons in the Representation Clause of the Constitution (where slaves were counted as 3/5 a person for determining seats in Congress) was intended to mean slaves and therefore “all the guarantees of personal liberty given to persons belong to slaves also.” From there, the convention reasoned, fugitive slaves were among the “people” who “were guaranteed the right to bear arms and of course by implication to use them.”36

The rhetorical skirmishes over the idea of armed self-defense carried none of the risks of actually fighting with a gun, and there are many reminders that using a gun in self-defense was no guarantee of a good or just result. Certainly the gods were distracted in 1836 when a fugitive in southern Ohio grabbed a rifle to protect his family against a gang of kidnappers. He used his single shot to no avail, was quickly subdued, and then stomped to death. That same year, two black fugitives managed to acquire rifles and escape from Missouri into Illinois. They poached some livestock and were cooking dinner when pursuers surrounded them and demanded their surrender. The fugitives decided to fight. The decision left one of them dead and the other apprehended on charges of escape and attempted murder for wounding one of the slave catchers.

Successful and not, continuing episodes of resistance show a budding culture of gun ownership and a commitment to self-defense. Civil-rights activist James Forman would comment in the 1960s that blacks in the movement were widely armed and that there was hardly a black home in the South without its shotgun or rifle.37 Anyone surprised by this should reflect on the early episodes of entire well-armed communities turned out against slave catchers in defense of fugitives.

This is evident in 1836, in Swedesboro, New Jersey, where a black family was captured by a professional bounty hunter and held in the basement of a local tavern. A little before midnight, forty black men—neighbors and friends of the captives—armed with rifles, muskets, and pistols, riddled the building with bullets and grape shot. The tavern owner, now ad hoc warden, got the worst of the deal. His building was ventilated and his return fire hit no one except a white bystander.

The armed community was in evidence again when fugitive Thomas Fox of Red Oak, Ohio, was apprehended by bounty hunters from Kentucky. The commotion brought out his neighbors, who confronted the Southerners and freed Fox. Several weeks later, on a Sunday morning, slave agents returned to the neighborhood with reinforcements and dragged a black man out of church. An armed, interracial group of rescuers assembled on horseback and interdicted the kidnappers, who released their black quarry without a fight.38

But this respite was only temporary. The Kentuckians were soon back across the border, this time eighteen strong and well-armed. They quickly encountered an armed group dead set against any neighbors being carted back to slavery. This time, the slave catchers identified a young woman, Sally Hudson, as a runaway and moved to seize her. When Sally tried to flee, one of them shot her in the back. This was deemed so cowardly by both sides that it actually diffused the conflict. To the disgust of local abolitionists, an Ohio grand jury refused to indict the man who killed Sally Hudson.

Fig. 2.5. Farmer with a gun. (Illustration by E. W. Kemble, from Paul Laurence Dunbar, The Strength of Gideon and Other Stories [1900].)

When racial violence broke out in Cincinnati in 1841, blacks took up arms and fought the surging mob. Initial press reports claimed multiple white casualties, but final assessment showed that only one man, an instigator from across the river in Kentucky, was killed.39

The scene repeats in 1844 in Chester County, Pennsylvania, where slave catchers again encountered an assembly of resisters. The slavers’ target was a black man named Tom who lived with his family on the Myers’ farmstead. As the man-hunters broke through the door of his cabin, Tom grabbed an ax and gave battle. One of the slave catchers fired his pistol in an attempt to cow Tom and his wife, now wielding an ax of her own. The warning shot went astray and actually hit one of the slave catchers.

The gunshot also alerted Tom’s neighbors, who ran to help, carrying guns, axes, and garden tools. Three of the slave catchers ran to seek help for their wounded man. Two of them stayed behind, guarding Tom and nervously threatening death to anyone who interfered. Sensing his advantage, one bold black man, pistol in hand, stepped forward, seized Tom, and freed him. Their bluff called, the slavers now implored some whites in the crowd to protect them from the circling Negroes. The threat was staunched when a constable arrived and arrested the Southerners for kidnapping.40

The willingness of neighbors and loosely knit groups to come to the rescue sometimes exceeded their effectiveness. But the fashion in which they appeared shows a more than incidental rate of gun ownership. In 1847, in Dauphin County, Pennsylvania, ten fugitive slaves were captured by slave agents from Maryland. They had been hiding out on the farm of a Pennsylvania abolitionist. After an initial confrontation of bluff, bluster, and retreat, both sides sent for reinforcements. Responding to the call, close to forty armed black men arrived on horseback from nearby Harrisburg. This time the putative rescuers were ineffective. The slavers’ reinforcements had arrived first, taken their human property, and were already away.

Sometimes loose confederations of ordinary folk with guns propped up a failed official response. Beginning in 1847, Kentucky slaver John Norris started a years-long quest in pursuit of a family of slaves who had escaped from his Boone County farm. Eventually, Norris captured several of his runaways, who were living free in Michigan. Traveling with his prize through Indiana, Norris encountered difficulties in South Bend, where more than one hundred residents, armed with guns and clubs, slowed him long enough for local abolitionists to get a sheriff’s order for release of the blacks. Norris and his cohorts brandished pistols and denied the sheriff’s authority.

Defying the sheriff turned out to be easier than confronting the second wave of black men who arrived in response to some unrecorded call for assistance. Variously reported as seventy-five to four hundred strong, the group, organized in military fashion, entered the village “in companies.” Against this show of force, Norris gave up the chase, retreated south, and filed a lawsuit that dragged on for seven years before granting him a small measure of relief.41

In the border states of the lower North, slaves often depended on the help of sympathetic whites who typically had better resources and easier access to firearms. A century later, strategists in the modern civil-rights movement would worry about political violence alienating sympathetic whites. There was some risk of that under slavery as well. Abolitionists were a slim minority of the population. Many were avowed pacifists. But some abolitionists actually were friendly to violent slave resistance.

In 1838, for instance, Illinois abolitionist Gamaliel Bailey applauded fugitive slaves who defended themselves with guns. Moving beyond rhetoric, a Pennsylvania abolitionist in Indiana County warned slave catchers to be careful of local Negroes, “as they were armed, had guns and knives and most likely would fight.” What he didn’t tell the man-hunters was that two of these fugitives worked on his farm and he was certain they were armed because he gave them the guns.42

Negroes with guns were a fleeting comfort for abolitionist missionary Jarvis Bacon, who in 1851 attempted to guide a group of fugitives out of Kentucky to a free labor settlement in Ohio. The escape plan was detected by patrollers before it really got started. Obviously thwarted, the “well-armed” fugitives still decided to fight, killing one of the pursuing posse and wounding four others.43

In a high-profile incident in 1852, two slaves owned by a Georgia congressman were aided in flight from Washington, DC, by white abolitionist William Chaplin. Hidden in Chaplin’s carriage, the fugitives were jolted to a halt when district police jammed a fence rail into the carriage spokes and stormed in.

The episode is notable because of the technology. Many early reports of fugitive resistance describe the discharge of firearms followed by hand-to-hand combat. The implication is that the resisters were armed with common, single-shot firearms. Developing repeating technology was relatively expensive and probably harder for free blacks and fugitives with meager resources to acquire.

Reflecting the status of their patron, Chaplin’s charges had state-of-the-art revolvers. As the lawmen pounced, Chaplin and the fugitives fired in anger and got an equal measure in return. They exchanged nearly thirty shots before the slaves and Chaplin were finally subdued. That same week, two captured slaves in transit back to Maryland pulled out hidden pistols and opened fire in a renewed attempt to escape. These men, it seems, were equipped with single-shot technology and with guns empty, were easily subdued.44

The 1850 Fugitive Slave Law gave Negroes new things to worry about. It pressed government agents and even civilians into the aid of slave catchers. This amplified threat was both practical and symbolic, and blacks responded with renewed vigilance. When a black man was apprehended in New York and remitted to his owner, the community reacted by “arming to the teeth” and forming mutual-aid committees against further incidents.

The new fugitive law also escalated the war of rhetoric. Hyperbolic abolitionists warned that even white people were at risk. One radical pamphleteer argued, “there are in the South, already, slaves as white as any of us, who have in our veins the purest Saxon blood. . . . The whiter the slave—especially if it is a female—the more extravagant the price. The more desirable the victim.”

There was actually a flash of this in New Albany, Indiana, where an apparently white woman, her daughter, and her grandson were handed over to an Arkansas slaver whose claim satisfied the legal formalities. This type of incident seems rare. More common was the objection of Northern whites that the new law dragooned them as “slaves” into the man-hunting business.

The Fugitive Slave Law also chased some blacks farther north into Canada. In 1850, a body of 150 fugitives fled Pennsylvania, determined to fight anyone who stood in their way. According to one sympathetic report, “many are armed and resolve to be free at all hazard, an attempt to arrest them would be no child’s play.”

The pressure of the 1850 law also pushed more blacks to advocate political violence. In Chicago, a group of three hundred assembled to endorse a pact of mutual self-protection against stalking slavers. Their preamble expressed a preference to avoid violence, but the operative provisions promised that no matter what the law said, “if driven to the extreme,” these Negroes would “defend themselves at all hazards.”

In Ohio, a similar meeting produced the resolution that “all colored people go continually prepared that they may be ready at any moment to offer defense in behalf of their liberty.” This reference to going prepared does not explicitly mention firearms. But in Philadelphia, the articulated resolve of a similar group following an abduction of a well-known member of the community was plain. They advised the “colored race to arm themselves and shoot down officers of the law” complicit in the capture of fugitives.

Some of the most explicit advocacy of political violence came from interracial gatherings of antislavery groups. In December 1850, short months after the new statute was passed, Robert Purvis, a black conductor on the Underground Railroad, spoke candidly to the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society. Black men, said Purvis, had a responsibility to arm themselves. Purvis argued that by standing up with arms and defending themselves, blacks would show the world that they were men and “not worthy of slavery.”

Some in the audience were avowed pacifists and urged Purvis to follow the example of Christ. Purvis’s answer was earnestly practical. “What can I do when my family are assaulted by kidnappers? I would fly and by every means endeavor to avoid it, but when the extremity comes, I welcome death rather than slavery and by what means God and nature have given me, I will defend myself and my family.”

In strongholds of aggressive abolitionism, the press openly urged fugitive slaves: “Arm yourselves at once. If the catcher comes, receive him with powder and ball with dirk or bowie knife or whatever weapon may be most convenient. Do not hesitate to slay the miscreant if he comes to re-enslave you or your wife or child.” Radical abolitionist Ohio congressman Joshua Giddings went further, claiming that blacks would not fight alone, that the white people of northern Ohio would engage in warfare to resist slave catchers and their federal-government enforcers.

As the rhetorical war escalated, armed resistance continued apace. In 1850 in Lawrence County, Ohio, six “well-armed” fugitives fired on a group of Kentucky slave catchers. Like many of these incidents, once the single shot firearms were spent, the Negroes descended on their pursuers with clubs, leaving them for dead and then escaping into the forest.

There was continued confirmation during this period that the results of violent resistance could vary dramatically. Pursued by slavers over the border into Indiana in 1853, a group of ten fugitives resisted with gunfire but were overcome by better-armed whites. With two slaves and one slaver wounded, the blacks were apprehended and carted back to an unrecorded fate.

Under the new Fugitive Slave Law, hunters of human property could now demand the assistance of United States Marshals. But this federal “authority” made little difference to blacks fighting for their lives. A willingness to defy the federal government and fight the marshals too was evident in 1850, in Coatesville, Pennsylvania, where a free black couple opened fire on a marshal and posse who were pursuing a fugitive in their care. Their firearms spent, the free man and his wife commenced fighting with axes, giving the fugitive cover to escape. Later, they displayed wounds from the fight as badges of honor.

A similar incident occurred in 1856 when Robert Garner, his wife, their four children, and two other adults fled out of Kentucky to Cincinnati. They were resting at the home of a free black man, Elijah Kite, when their Kentucky masters and a United States Marshal broke through the door. Both Kite and Garner responded with pistol fire, wounding one of the intruders.

The violence then took a horrific turn. Garner’s wife was the spark. Seeing that the men might lose the fight, Margaret Garner shouted that she would kill her children before returning them to the yoke. By the time the slavers and their government accomplice gained control, Margaret had strangled the life from her two-year-old daughter. For Northerners, Margaret Garner’s infanticide underscored the evils of slavery. Southerners said it was just another example of the baffling Negro and confirmation of his inferior status in law and in nature. After extended legal squabbling, the Garners were given up to their master, who sold them to slave traders in New Orleans.

Another US Marshal was the target of gunplay when an interracial group in the abolitionist bastion of Oberlin, Ohio, blocked the pursuit of Kentucky fugitive John Price. When the slave catchers and their federal man brought the fight, the resisters brandished guns, to a temporary stalemate. The aftermath reflected the simmering conflict between federal law and technically preempted state statutes that deemed slave catchers kidnappers. State and federal bureaucracies initiated disparate proceedings. The federal process charged the resisters with violating the Fugitive Slave Law. Ohio, on the other hand, indicted the marshal and three Southerners for kidnapping. The conflict eventually was settled with reduced sanctions against combatants on both sides.45

While Negro life in free states and territories was certainly an improvement over slavery, these places fell far short of the promised land. Opposition to slavery did not necessarily mean full political and social embrace of Negroes. This is evident in various free-state laws restricting Negro rights. Ohio’s early constitution denied free blacks the right to vote, and in 1807 the state passed a loosely enforced law requiring Negro immigrants to post a $500 bond and a guarantee of their good behavior signed by two white men. The Indiana Territory prohibited Negroes from testifying in court against whites. In 1857, Wisconsin voters reversed a previous statute granting black suffrage. An 1857 Oregon statute prohibited blacks from settling in the state. And Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, and Iowa all prohibited interracial marriage.

It was the violation of one of those interracial marriage bans in 1845 that sent Rose Anne McGregor of Marion County, Iowa, running for her gun. Rose Anne had the temerity to fall in love with a white man, Tom McGregor, and he with her. They beat the first prosecution for violating the ban by getting the proceedings moved to a Quaker community where a sympathetic grand jury refused to indict them.

Officials then ordered Rose Anne McGregor either to post manumission papers and a $500 bond or to be sold to the highest bidder. The McGregors were defiant and vowed to do neither. While Tom was away, the sheriff and a deputy came out to arrest Rose Anne. She saw them approaching and warned that she was armed and was a crack shot. It was one of those instances where just the threat of gunfire seemed to be enough, at least until nightfall. Under the cover of darkness, the sheriff sneaked to the door, kicked it down, and seized Rose Anne McGregor before she could get a shot off.

Rose Anne was captured, but not for long. As they trotted back to town with Rose Anne bound up on horseback, she kicked her mount hard in the ribs and held on as the animal bolted off into the night. She soon met up with Tom, and they abandoned their Iowa home in search of a more welcoming environment.46

The black tradition of arms ultimately elevates and enshrines the distinction between self-defense against imminent threats and organized political violence seeking group advancement. But in the fight against slavery, there was little concern for that distinction. In a practical sense, slavery was a state of war, and some in the burgeoning black leadership put it basically that way.

At the 1854 National Emigration Convention of Colored People in Cleveland, Ohio, black abolitionist Martin Delaney cast resistance to slavery as straightforward warfare, declaring, “Should we encounter an enemy with artillery, a prayer will not stay the cannon shot, neither will the kind words or smiles of philanthropy shield his spear from piercing us through the heart. We must meet mankind, then as they meet us—prepared for the worst.”

With an appreciation of the young nation’s revolutionary struggle, escaped slave Andrew Jackson defended his own and the broader use of violence in the pursuit of liberty, proclaiming, “If it was right for the revolutionary patriots to fight for liberty, it was right for me, and is right for any other slave to do the same. And were I now a slave, I would risk my life for freedom. Give me liberty or give me death would be my deliberate conclusion.” In Ohio around the same time, John Isome Gaines advocated a slave revolution to overthrow the slaveocracy and install a “government of God that would secure universal liberty and equality.”

Commenting on John Brown’s failed 1859 raid at Harpers Ferry, black abolitionist Charles Langston invoked America’s revolutionary principles, and with a plain note of sarcasm, declared that the “renowned fathers of our celebrated revolution taught the world that ‘resistance to tyrants is obedience to God,’ that all men are created equal and have the inalienable right to life and liberty. These men proclaimed death, but not slavery, or rather give me liberty or give me death.” On these principles, Langston argued, Brown’s raid and similar acts of resistance were entirely justified.

One of the most famous calls for violent resistance was David Walker’s “Appeal to the Colored Citizens of the World.” Walker urged his brothers in bondage to rise up and “kill or be killed.” He declared that “the man who would not fight . . . in the glorious and heavenly cause of freedom . . . ought to be kept with all his children or family in slavery, or in chains to be butchered by his cruel enemies.”

Similar sentiments were expressed by fugitives who escaped to freedom and became spokesmen for the race. Fugitive activist H. Ford Douglas, publisher of the Provincial Freeman, advocated the violent overthrow of slavery in unequivocal terms. Similarly, David Ruggles, founder of the New York Vigilance Committee, urged that blacks “must look to our own safety and protection from kidnappers, remembering that self-defense is the first law of nature.”47

In 1843, the Michigan Negro Convention repeated this theme, calling on blacks to wage “unceasing war” against the tyranny of slavery. Soon after that, in 1844, Moses Dickson formed a shadowy organization called the International Order of Twelve of the Knights and Daughters of Tabor, with the agenda of overthrowing slavery by any means. Pressing an agenda beyond abolition, Reverend Henry Johnson gave a militant speech at the 1845 Colored Suffrage Convention in New York, proclaiming that “the colored population were ready to take the musket, if necessary, to defend our churches, our family associations, and the rights of our neighbors.” The details and activities of many of these individuals and organizations are thinly researched, but a few episodes are more richly recorded.48

In 1848, Henry Highland Garnet advanced David Walker’s earlier appeal and indulged no fine distinctions between self-defense and political violence. Garnet characterized slaves as “prisoners of war in an enemy’s country” and urged, “by all the rules of war, you have the fullest liberty to plunder, burn and kill.” Garnet considered slavery a broad and continuing license for violent resistance. “If hereditary bondsmen would be free, they must strike the first blow. . . . It is your solemn and imperative duty to use every means intellectual and physical that promise success. . . . You had better all die—die immediately, than live as slaves and entail your wretchedness upon your posterity. . . . Let your motto be resistance! Resistance! Resistance!”

Garnet presented his address for inclusion in the platform of the National Negro Convention. The body rejected it, with the opposition led by Frederick Douglass and Charles Remond, at that stage still under the sway of the pacifist Garrisonians.49

But both Douglass and Remond eventually advocated violence as a tool for ending slavery. In June 1849, Douglass gave a speech in Boston that fairly shocked his audience of pacifist abolitionists. In language reflecting his emerging militancy, Douglass said that he would welcome slave rebellion in the South and would celebrate any news that “the Sable arms which had been engaged in beautifying and adorning the South, were engaged in spreading death and devastation.” Although the precise curve of Charles Remond’s transformation is unclear, his view had changed by 1851 when he celebrated the violence of three fugitive slaves who shot and killed their pursuing master.50

Militant rhetoric raised objections from pacifist abolitionist and sparked conflicts that illustrated the difference between black and white stakes in ending slavery. Henry Highland Garnet was a particular target of pacifist William Lloyd Garrison’s paper, the Liberator. White abolitionist Maria Weston Chapman denounced Garnet in a lengthy Liberator article, suggesting that he had fallen under the influence of “bad counsel.”51

The implication was that Garnet had not developed his own views but had been lured and manipulated into militancy by some shadowy white Svengali. Garnet bristled at the suggestion that “his humble productions have been produced by the Council of some Anglo-Saxon.” In a letter to the Liberator that models the objections of modern black contrarians to presumptuous white paternalism, Garnet chided, “I have expected no more from ignorant slaveholders and their apologists, but I really look for better things from Mrs. Maria W. Chapman . . . , editor pro tem of the Boston Liberator. I can think on the subject of human rights without ‘counsel’ either from men of the West or women of the East.”52

Despite pacifist discomfort, militant abolitionists continued to advance black resistance in heroic terms. The New York Independent observed,

The framers of this new [fugitive slave] law counted upon the utter degradation of the Negro race—their want of manliness and heroism—to render feasible its execution but it was the cowardly Negro, the worm and not the serpent upon whom they set their foot. They anticipated no resistance from a race cowed down by centuries of oppression and trained to servility. In this however they were mistaken. They’re beginning to discover that men, however abject, who have tasted liberty, soon learn to prize it and are ready to defend it.53

In some of the most widely reported revolts against the fugitive slave law, blacks, sometimes accompanied by radical white abolitionist allies, defied the authority of the state and attempted to snatch fugitives from the process of the law. In Syracuse, New York, in 1851, black and white abolitionists stormed the courtroom and rescued William McHenry of Missouri, who was offered up to his master under the 1850 law. Federal marshals beat back the crowd and retrieved McHenry, only to lose him again in the tumult.

McHenry was hustled off to Canada. But two dozen people, half of them Negroes, were indicted for violating federal law by aiding in the escape. Suggesting the sentiments of the community, three of the indicted whites were acquitted. Six blacks who were primary instigators, fled to Canada. One of that group, Reverend Jermaine Loguen, had already articulated his contempt for the 1850 law in print: “I don’t respect this law. I don’t. I won’t obey it! It outlaws me, and I outlaw it and the man who attempts to enforce it on me. I place governmental officials on the ground that they placed me. I will not live a slave, and if force is employed to re-enslave me, I shall make preparations to meet the crisis as becomes a man.”54

A similar incident occurred in 1851 in Boston, where fugitive Frederick Wilkins was apprehended and taken into custody on the strength of the 1850 law. In a tactic that was repeated in Ohio, Pennsylvania, New York, and elsewhere, and in overt defiance of any government authority over Wilkins, Negroes burst into the courtroom, stole Wilkins away, and skirted him off to Canada. When two blacks and two whites involved in the rescue were acquitted on state charges, President Millard Fillmore threatened federal prosecution against the “lawless mob.”55