“The Winchester rifle deserves a place of honor in every Black home.” So said Ida B. Wells.

What would drive a four-and-a-half-foot tall colored schoolteacher to say such a thing? What did she witness? What did she fear? What were the rumors and threats that shrouded her rise from slavery to the vanguard of the black freedom struggle? And what was the culture that allowed this eminent leader of the race to exalt a gun that was the assault rifle of her day, without censure and, indeed, to wide affirmation?

Wells came of age during the period many consider the nadir of the black experience in America. She witnessed the violent defeat of Reconstruction and chafed under the menace of John Lynch and the indignities of Jim Crow. It was a period filled with hazards where the government was not just neglectful of Negro security but was often an overt menace. Wells’s praise of the Winchester reflected hard lessons and worries about the next dark night, passed along on the whispers of black folk.

By age twenty, Wells had been orphaned by a yellow-fever epidemic; had become caretaker of her siblings; and had moved from her childhood home of Holly Springs, Mississippi, to Memphis, where a coveted teaching contract introduced her to the city’s black elite. It was the start of her journey into journalism, publishing, and her destiny as America’s foremost antilynching crusader.

Memphis in 1881, was a relative haven of opportunity for Negroes, whose performance on criteria like employment and arrest rates would be the envy of modern policy makers. But other aspects of the climate in Memphis were not so salutary. Blacks and Irish immigrants competed for much of the same low-cost housing and unskilled work. Black war veterans were natural combatants with the Memphis police force, which was 90 percent Irish and was described by a white army officer as “far from the best class of residents.”

Political leaders of the period were candidly unsympathetic to Negro interests. Tennessee governor William Brownlow hopefully predicted that, with no masters to care for them, most Negroes would perish from starvation and disease within a generation. It turned out that these folk were of heartier stock.1

Ida Wells’s fighting instinct first erupted on board a Chesapeake and Ohio passenger train. The traveling strategy for colored ladies of the day was meticulous grooming and impeccable manners, with the hope of avoiding the demeaning, random ejections from the first-class car. Wells pursued this strategy in the fall of 1883, but would only play the game so far.

When she handed her first-class ticket to the conductor, he ordered her to move to second class. Wells ignored him and turned to her novel. Provoked by her impudence, the conductor grabbed her luggage and hissed that he was attempting to treat her like a lady. Wells answered that he should leave the lady alone. Now fed up, the conductor grabbed at Wells, intent on dragging her out like cattle.

Wells set her feet wide against the seat-front and clutched hard into the headrest. When the conductor tried to pry her away, she sank her teeth into his hand. She was defeated only after several passengers helped the bleeding conductor lift away the entire seat section where Wells was anchored and throw it and her into the smoky second-class car.

Bruised, her dress torn, and her ego battered, Wells left the train at the next stop, to the jeers of the first-class passengers. The episode triggered the first stage of her activism. She sued the C&O Railroad and followed with a series of lawsuits against other rail lines. Some companies responded with separate cars for black first-class passengers. Although the accommodations were rarely first-class in fact, the United States Supreme Court soon affirmed the constitutionality of these so-called separate but equal accommodations.

Wells began her activism suing railroads, but she built her legend fighting lynching. Early on, like many respectable black folk, she tried to distance herself from the terror of lynching by thinking about it as only a sort of disproportionate justice inflicted on black criminals. That changed in 1892 with the triple lynching of Tom Moss, Calvin McDowell, and Will Stewart.

Moss was a good friend of Wells’s. He was president of People’s Cooperative Grocery, which served the predominantly black Memphis community along Walker Avenue, known as “the Curve.” People’s Grocery was new competition to a store run by W. H. Barrett. Barrett was white, but he relished the profits from selling to blacks in the racially mixed neighborhood around the Curve.

The violence that ended in the lynching of Tom Moss started with a fight between black boys and white boys over a game of marbles. Angry that his son had come out badly, Cornelius Hearst took a horsewhip to one of the black kids. A group of angry black fathers then gathered outside Hearst’s home and incidentally next to People’s Grocery.

As tension built, W. H. Barrett exploited rumors of impending black violence to convince a local judge to issue arrest warrants for “agitators” who gathered around People’s Grocery. Armed with the knowledge that the warrants would be served, Barrett then spread the rumor that a white mob was intending to raid the store.

The managers of People’s Grocery got their guns and prepared for the attack. When they saw a group of armed men approaching the back of the store at around ten o’clock that night, their fears seemed confirmed. The advancing group, none of them in uniform, actually was deputized and charged with serving the warrant instigated by W. H. Barrett. There is dispute about who fired the first shot. But it is clear that three deputies were wounded in the exchange of gunfire.

While bystanders fled, the remaining deputies sent for reinforcements, and the occupants of People’s Grocery were arrested. Tom Moss was not among them but was later described as the ringleader and the person who shot at least one of the deputies. Moss claimed to be at home with his wife during the gunfight, and another man was initially charged with firing the shot later blamed on Moss. The white press depicted the event as a bloody riot and ambush by a murderous band of Negroes. Scores of white men were deputized. They arrested at least thirty alleged conspirators.

Fearing mob action, a black militia guarded the jail for two nights. But on the third night, the black guard dissolved. With the jail unguarded, a crowd seized Tom Moss, Calvin McDowell, and Will Stewart, dragged them to a spot north of town, beat them, gouged their eyes, and finally—mercifully—shot them.

Lynching was nothing new in in this era. But the killing of Moss, McDowell and Stewart was different. It was the first time in Wells’s experience that “respectable” black folk had been lynched. None of the men had any sort of criminal record and all of them worked in jobs that were essentially middle-class. The killing of Tom Moss also was intensely personal for Wells. She was godmother to his daughter and she wrote later that Moss and his family were her best friends in Memphis.

Black reaction to the lynching ranged from outrage to fearful talk of leaving the city for destinations as varied as Liberia and newly opening territory in Oklahoma. Wells was not in Memphis the night of the lynching, but when she returned, she wrote an angry editorial charging that Memphis had “demonstrated that neither character nor standing avails the Negro if he desires to protect himself against the white man or become his rival.” Wells condemned the city’s attempt to disarm black citizens and ban gun sales to blacks while deputizing white men and boys to enter black homes, seize firearms, and help themselves “to ammunition without payment.”2

The lynching provoked wide outrage in the black press, with angry calls for justice and even vengeance. The Kansas City American Citizen editorialized that the lynching “called for something more than patient endurance—it calls for dynamite and bloodshed.” The Langston City Herald asked, “what race or class of people on God’s footstool would tolerate the continual slaughter of its own without a revolt?”

Wells joined the charge, expanding her criticism to the federal government and black federal officeholders, asking, “where are our leaders when the race is being burnt, shot, and hanged?” This was partly a condemnation of vanishing federal support for blacks under the collapse of Reconstruction, but it also targeted the handful of Negroes on the public payroll who feared that agitation would jeopardize their positions.

At a practical level, Wells responded in familiar fashion. Prompted by the inability of even well-intentioned public officials to stop eminent violent threats, she explained later, “I had bought a pistol first thing after Tom Moss was lynched.” She was in some sense tardy in this precaution. Over in Nashville, eighteen-year-old W. E. B. Du Bois, a freshman at Fisk University, observed in 1886 that his classmates, shaken by the rising tide of lynchings, were habitually armed whenever they ventured into the city.3

Wells now developed a sharper critique of the nature and impulse for lynching. She had seen black criminals lynched. But this was different.

I had accepted the idea meant to be conveyed—that although lynching was irregular and contrary to law and order, unreasoning anger over the terrible crime of rape led to lynching; that perhaps the brute deserved to die anyhow and the mob was justified in taking his life.

But Tom Moss, Calvin McDowell, and [Will] Lee Stewart had been lynched . . . with just as much brutality as other victims of the mob; and they had committed no crime against white women. This is what opened my eyes to what lynching really was. An excuse to get rid of Negroes who were acquiring wealth and property and thus keep the race terrorized and keep the “nigger down.”

During the period that white America dubbed the Gay Nineties, lynchings of blacks in the South averaged about two per week. Wells’s increasingly cutting assessment of the terror launched her into dangerous territory. She started suggesting that frequent claims of rape by white women proved too much. “Eight Negroes lynched since last issue of the Free Speech . . . on the same old racket, the alarm about raping white women. If southern white men are not careful, they will overreach themselves and public sentiment will have a reaction; a conclusion will then be reached which will be very damaging to the moral reputation of their women.”4 The implication here was incendiary. The Memphis Commercial fulminated that southern white men would not long tolerate “the obscene intimations” of Wells’s editorial. It was an accurate assessment.

Wells was in New York when white men went on the warpath. Before it was over, Wells’s coeditor at the Memphis Free Speech was run out of town, and the paper’s offices were destroyed. Wells was warned that it would hazard her life to return. She decided to stay in New York after learning that some of the black men of Memphis were risking their lives by organizing an armed squad to protect her.

Ironically, being exiled from Memphis launched Wells onto the broader stage of New York City and dramatically widened the audience for her work. With her investment in the Memphis Free Speech consumed by the mob, Wells joined T. Thomas Fortune’s New York Age, where her reporting would garner national and international recognition.5

From New York, Wells’s attack was unrelenting. She struck hard at the myth that lynching was the product of the lawless element. She hammered the shibboleth of black rapists, arguing that the facts clearly viewed would “serve . . . as a defense for the Afro-American Samsons who suffer themselves to be betrayed by white Delilahs.” Then, without the cover of euphemisms, she stated boldly that “there are many white women in the South who would marry colored men if such an act would not place them at once beyond the pale of society and within the clutches of the law.”

Her most blistering tactic was to use white sources and reporting to make her case. She reveled in the report of Mrs. J. C. Underwood, an Ohio minister’s wife who claimed she had been raped by a black man, then recanted, acknowledging the “strange fascination” the Negro had for her. She admitted to lying about the rape on the worry that she might have contracted venereal disease or become pregnant with a black child.

Wells found plenty of other fodder in the southern papers. In one short spate, the white Memphis press covered six cases of white women taking black lovers. From all across the South, Wells gathered stories showing poor, middle-class, and affluent white women, the prostitute and the physician’s wife, as willing sexual partners with black men. She reprinted news of white women who had given birth to black children and refused to name the father. She gloried in a Memphis Ledger report in June 1892 decrying the circumstances of Lillie Bailey, “a rather pretty white girl, seventeen years of age, who . . . is the mother of a little coon” and refused to identify “the Negro who had disgraced her.” For Wells this demonstrated that the pretty white girl had some affection for the father of the “little coon.”6

Along with her ever more incisive critique of lynch terror, Wells developed a keener sense of the necessity and value of defensive firearms. Celebrating the recent evidence of blacks defending themselves and preventing lynchings through armed self-defense in Jacksonville, Florida, and Paducah, Kentucky, she advanced her classic prescription for armed self-defense. “The lesson this teaches and which every Afro-American should ponder well, is that the Winchester rifle should have a place of honor in every black home. The more the Afro-American yields and cringes and begs, the more he is insulted, outraged and lynched.”7

It was a bold prescription, perhaps even foolhardy. But Wells was keenly aware of the hazards. She understood firsthand from the lynching of Tom Moss the danger of drawing guns, only to be outnumbered and finally outgunned. But she also saw clearly the potential utility of firearms and the moral case for fighting back against violent aggressors. The implications of this simple insight, ancient in its roots, would resonate throughout her life’s work.

Like Frederick Douglass, who advised Negroes to acquire a good revolver against the threat of slave catchers, Wells seems to have avoided getting into any gunfights. Indeed, while we know that Wells purchased a pistol after Tom Moss was lynched, it is not clear whether she actually owned a Winchester rifle. But the circumstances of Wells’s purchase of part interest in the Memphis Free Speech newspaper are suggestive.

Wells shared ownership in the paper with Reverend Taylor Nightingale. Pushed by the mounting anger over a Free Speech editorial applauding Negroes’ violent response to a lynching in Georgetown, Kentucky, Nightingale would flee Memphis for the Oklahoma Territory. The style of the editorial suggests that Wells actually wrote it:

Those Georgetown Kentucky Negroes who set fire to the town last week because a Negro named Dudley had been lynched, show some of the true spark of manhood by their resentment. We had begun to think the Negroes—where lynching of Negroes has become the sport and pastime of unknown (?) White citizens—hadn’t manhood enough in them, to wriggle and crawl out of the way, much less protect and defend themselves. Of one thing we may be assured, so long as we permit ourselves to be trampled upon, so long we will have to endure it.8

Although this was likely Wells’s work, the editorial was unsigned and the immediate blame was laid on Nightingale, whose known militancy included urging everyone in his congregation to buy Winchester rifles. Wells and Nightingale were sympathetic friends, and perhaps both of them found the idea of the Winchester simply a potent rhetorical tool. But at least one researcher concludes that Nightingale did in fact own a Winchester rifle. And given the times, it would be no surprise if both he and Wells counted Winchesters among their important possessions.

The Winchester reference appears again in the public bickering between Wells and black leaders in Memphis. Writing from New York, Wells poked again at the rape theme, asking facetiously why white women of the South were so often in the position to cry rape so long after the supposed fact. Attempting to keep the city from exploding over the insult, black minister B. A. Imes published a letter criticizing Wells, including a gratuitous attack hinting at promiscuity. Wells answered with her own personal attack, demonstrating to all that Reverend Imes was overmatched. This actually built sympathy for Imes and raised the objection that it was unfair for Wells, sitting in New York, to criticize people like Imes, who remained “in a bloody city while looking along the barrel of a ready Winchester.”9

The repeated references to the Winchester seem purposeful. It was the state-of-the-art repeating rifle of the day. One formal review of the Henry Model Winchester reported “187 shots were fired in three minutes and thirty seconds and one full fifteen shot magazine was fired in only 10.8 seconds. A total of 1,040 shots were fired and hits were made from as far away as 348 feet at an 18 inch square target with a .44 caliber 216 grain bullet.” This gun was the assault rifle of its day. With its medium-range ballistic superiority (compare the Winchester’s .44 caliber, 216 grain projectile to the .22 caliber, 55 grain AR-15 round), it still surrenders little to its twenty-first-century progeny.10

When Ida Wells advised black folk on the virtues of the Winchester rifle, one of her practical examples was the averted lynching in Paducah, Kentucky. She was referencing the episode in July 1892 where, following another lynching just a month earlier, a Negro was arrested for peeking into windows at white women. Primed for the threat, community men gathered to guard the jailhouse. As expected, a group of white toughs eventually showed up.

With no attempt to parlay, the Negroes fired on them, fatally wounding one. For whites, this confirmed rumors that blacks had been stockpiling weapons and planning retaliation for the earlier lynching. Local papers warned of the race war to come.

The governor sent in the state militia, and police seized guns from the hardware stores and distributed them among the white men of Paducah. For blacks, they took the opposite approach, searching black homes and confiscating firearms. In a natural survey of the scale of Negro gun ownership, they seized more than 200 guns from black homes. Eventually tensions subsided to an uneasy peace.11

The second averted lynching occurred on July 4, in Jacksonville, Florida. In the early afternoon, a Negro teamster named Ben Reed and a white shipping clerk at the Anheuser-Busch brewery got into a row over Reed’s tardiness in making a delivery. The shipping clerk was a young man, excited to close down early and join the Independence Day festivities. Reed was pushing forty and resented the harsh talk from a white kid. They exchanged insults, then blows. The combat escalated as they attacked each other with the tools and hardware of the loading dock. By the end of it, Ben Reed was in police custody, charged with the murder of the young white man.

As the news spread, so did the lynch rumors. Considering the times, the response of the black community was no overreaction. The Florida Times-Union provided the account that would soon make its way to Ida Wells.

Every approach to the jail was guarded by crowds of negroes armed to the very teeth. The city was virtually under their control. . . . Sentinels stood on every street corner, and when a white man would pass they would question him about where he was going, etc. A whistle signal would then be passed on to the next corner and the pedestrian would be surrounded and followed. If he went in the direction of the jail, the Negroes would close in upon him and he would soon find himself covered by fifty or more cocked revolvers. He would be interrogated again and after being treated to abusive language would then be ordered to go back.

Over the next three days, the crowd of armed Negroes surrounding the jail grew to nearly one thousand, and a counterforce of whites began pouring in from as far away as north Georgia. Finally, on July 7, a show of force by the governor’s militia, brandishing a Gatling gun, and a spate of torrential rains dispersed the crowds without bloodshed. Except for the cocksure young man who goaded Ben Reed, no one died in those tense moments at Jacksonville. Reed was convicted of murder and sentenced to life imprisonment at hard labor.12

Other, similar episodes confirmed the potential for Negroes with guns to thwart lynch violence. In 1888, in the village of Wahalak, Kemper County, Mississippi, armed black men exchanged gunfire with an impromptu posse that pursued a black kid into the Negro quarters. The black boy had fought a local white kid to a draw. This prompted a band of Kemper County men to ride to the defense of white superiority. Two whites and several blacks were killed in gunfire. But the Negro boy who dared to come out even in a fair fight was not lynched.13

In 1899, in the town of Darien, Georgia, a prominent black man was jailed on the familiar charge of rape. The rumor spread that the sheriff planned to turn him over to the mob. The blacks of Darien were numerous and organized enough to thwart the mob with armed sentinels posted at the jailhouse and an understanding that folk should rush to the jail if they heard the bell of the nearby Baptist church. These defensive efforts were a troublesome show of defiance to whites who dubbed it the “Darien Insurrection.”14

Of course, these arguably salutary results are not the full story. Legitimate or not, violence can unleash a whirlwind. The background worry of armed blacks provoking white backlash is illustrated by a lynching in Mayfield, Kentucky, just thirty miles from Paducah. The spark was the fear of black retribution for earlier lynchings nearby.

Jim Stone, one of the Negroes who would die in Mayfield, was rumored to be the leader of the conspiracy. The evidence of an impending Negro attack was the unusual insolence of Mayfield’s blacks and the fact that they were increasingly going about armed. That was enough to send the mob after Jim Stone, who was lynched in December 1896.

There was no community intervention against the lynching of Jim Stone. But there was suspected retaliation in the form of mysterious fires and the shooting of a white man who boldly ventured into a black saloon. The violence culminated with the deputizing of one hundred white men who attempted to fully disarm the blacks of Mayfield. These deputies tore through the community, burned four homes, and shot up others. By the end of it, now mostly disarmed and cowed, the blacks who had not fled delivered a hundred-signature petition to the municipal government, praying to end hostilities and promising no more revenge for the recent lynchings. Their terms of surrender were accepted, and a peace of sorts was restored to Mayfield.15

The ending was similar in Danville, Virginia, where a gunfight precipitated a cycle of violence. It was 1883, and tensions were already high in anticipation of upcoming elections when black and white men passed too close on the sidewalk. Arms touched. The white man took offense. They argued, and the black man’s insolence sent the white man for his revolver. They scuffled and that drew a crowd, and then there was gunfire. By the end of it, three black men and one white were killed, and six blacks and four whites were wounded. Armed whites then locked down the town, warning Negroes to stay off the streets. This climate suppressed the black vote on Election Day and helped Democrats to prevail.16

Although diminished compared to the Civil War period, black political violence continued into the late nineteenth century. The populist movement of the era offers good examples. Ideally, populism subordinated racial distinctions to shared values and political concerns of the working class. In practice, race still trumped. But despite the failed ideals of racial harmony, the impulse toward collective action by working people still generated episodes of armed resistance that contribute to our thinking about the black tradition of arms.17

In Jefferson County, Georgia, populist leader Thomas Watson made direct appeals to black voters and exhorted mixed-race audiences of populists. Although Watson rejected black and white social equality, he pressed the common political concerns of working men. Campaigning in 1892, Watson appeared on the stage with Negro populist Reverend H. S. Doyle. Doyle’s life was threatened several times during the campaign, and a shot fired at him during a Jefferson County meeting actually killed a white man in the crowd. When Doyle was subsequently targeted for lynching, he retreated to Watson’s farm, where two thousand armed populists, black and white, rallied to guard him.18

In 1886, in Lasky County, Arkansas, about forty Negro workers affiliated with the populist Knights of Labor, struck the Tate plantation, seeking a wage increase. The Knights had enjoyed some recent organizing success, and that spurred the black men to further militancy. They boldly warned the local sheriff not to interfere with their strike. He dismissed the warning and rode with help to break them up. When one of the workers confronted him, the sheriff shot the man, wounding him. The gunshot drew attention, and soon the sheriff and his little squad were surrounded by 250 armed Negroes. The sheriff retreated but later returned with reinforcements. By then, many of the black men had dispersed. The remaining strikers briefly resisted, but after a few volleys of gunfire, they scattered.19

In Leflore County, Mississippi, Negro farmworkers of the Colored Alliance overplayed the power of bluff after one of their leaders was threatened. They drafted an angry letter, promising to defend their leader by force, and signed it “3000 armed men.” Then 75 of them assembled in military order and marched to town to deliver it. While many of them were armed, they were not three-thousand-strong. Their letter fueled rumors that blacks were massing for an attack. Soon, the call was out to the governor, who sent in three companies of Mississippi National Guard. This force, accompanied by a large group of armed civilians, plus the sheriff with his own force, rode out after the supposed conspirators. Before it was over, scores of Negroes were shot down.20

In the modern debate, many approach armed self-defense empirically, extrapolating from general trends whether or not it is a good bet. Some object that this strips out variables that make every case unique and demand private choice. Others invoke higher principles and exalt even failed self-defense as heroism.

Ida B. Wells fit into this last group. Where some saw foolish, fruitless acts of armed resistance, Wells saw the stuff of legend. This is nowhere more evident than in her 1900 paean to Robert Charles of New Orleans. The white press called Charles a lawless desperado. But Wells projected the evident black consensus that Charles was the “hero of New Orleans.”21

Robert Charles was conceived in slavery but born into freedom in the vicinity of Vicksburg, Mississippi. He was a decently hard worker, with a man’s fondness for liquor and women. Like many men of the time, he habitually carried a pistol.

The extent of this practice is suggested by studies of southern convict labor schemes, which used the charge of carrying a concealed weapon and other minor offenses like vagrancy, using obscene language, and selling cotton after sunset, to funnel cash-poor black men into a system that leased them out to whoever paid their fines. The crime of carrying a concealed weapon, enforced primarily against Negroes, was, by the turn of the century, one of the most consistent methods of dragooning blacks into the system.22

So it was not unusual that Robert Charles and his friend Leonard Pierce tucked .38 caliber Colt revolvers into their belts and headed out into the sticky July evening. At around 11:00 p.m., Charles and Pierce were sitting on the stoop of a row house, awaiting the return of Charles’s sister and her roommate, when two white New Orleans policemen approached. The progression from “What’s your business here?” to violence was quick.

As Charles attempted to stand, one of the cops grabbed him. Charles pulled back, and the cop drew his club and then his revolver. Charles drew his own gun and they both fired, each taking nonfatal bullet wounds. Charles took off, leaving Leonard Pierce behind. Pierce identified Charles and told police where to find him.

Slowed by his wound, Charles eventually made it back to his rented room, where he retrieved his Winchester rifle. The New Orleans police were not far behind. A squad of them approached and yelled for him surrender. Charles flung open the door and killed the captain with a bullet to the heart. Then he fired on two others, killing one of them with a shot through the eye. Two more in the rear retreated to an adjacent apartment. Charles stalked them briefly and then fled.23

The flight of Robert Charles precipitated more than a police manhunt. It provoked a mob that ranged through the city, attacking targets of opportunity. It then descended on the parish prison, aiming to lynch Leonard Pierce. The prison was well defended, and there were no jailers willing to hand over Pierce, so the mob went back to random attacks. By morning, mobbers had killed three blacks and beaten approximately fifty others.

The next day, police investigated a tip that Charles was hiding out in the home of friends on Saratoga Street. Charles had been there for hours, casting bullets and loading cartridges. As two officers entered the building, Charles shot them both with a barrage from his Winchester.24

In the street, the crowd that had followed the cops was growing by the minute. By the early evening, one thousand armed men surrounded the building. Soon there would be more than ten thousand. People ducked for cover when Charles popped up from a second-story window and opened fire, killing one man in the crowd. Thoroughly surrounded, Charles surely appreciated that this was where he would die.

The details of the gun battle seem embellished over time, with reports of five thousand shots fired into the second story where Charles huddled. If the reports are to be believed, Charles’s marksmanship and his capacity to avoid return fire were uncanny. Under a deluge of gunfire, Charles got off another fifty shots, killing two men in the crowd before finally succumbing to multiple wounds. Charles was dead, but the unsated mob spread through the city, killing three more Negroes and burning a black school.

The incident is partly an affirmation of the danger of spillover and escalation from one incident into a cycle of violence and retribution. But it also raises the question, what motivated Robert Charles? Some contend that Charles was smoldering over the grotesque lynching of Sam Hose in Newman, Georgia, and focused his ire on the state government, which had recently stripped the vote from blacks. When his first victim, the New Orleans flatfoot, drew his club and pistol, Charles was already primed for war. Other reports said that Robert Charles was driven mad by cocaine. Republicans and Democrats said the episode demonstrated the worst ramifications of the opposing party’s policies. The Democratic press painted Charles as a prime example of a dangerous breed, the “bad nigger.”25

For all the carnage he wrought, Robert Charles received remarkably sympathetic treatment from Ida B. Wells. But her assessment ranged far beyond the immediate conflict. For Wells, the incident was part of a broader current that included the lynching of Sam Hose, who had killed his employer in self-defense, and a dozen other lynchings that she had covered in the previous few months. The root problem, Wells said, was the cops’ “assurance born of long experience in the New Orleans service . . . that they could do anything to a Negro that they wished,” even though Charles and Pierce “had not broken the peace in any way whatever, no warrant was in the policeman’s hands to justify arresting them and no crime had been committed of which they were suspects.”

Just as she did in the attacks on lynching, Wells turned white press reports to her advantage. The Times Democrat revealed the reason Charles and Pierce were confronted in the first place. The neighborhood had been “troubled with bad Negroes” and the neighbors were complaining to the Sixth Precinct police about them. Charles and Pierce had been sitting on a doorstep long enough that someone considered them suspicious, and police came to run them off.

Some would say that the greatest hazard was the black men carrying guns in the first place, that Charles was no hero but was simply foolish. But Wells’s depiction of Charles’s last stand sounds like a Texan describing the heroes of the Alamo:

Betrayed into the hands of the police, Charles, who had already sent two of his would-be murderers to their death, made a last stand in a small building, 1210 Saratoga St., and still defying his pursuers, fought a mob of 20,000 people single-handed and alone, killing three more men, mortally wounding two more and seriously wounding nine others. Unable to get him in his stronghold, the besiegers set fire to his house of refuge. While the building was burning Charles was shooting, and every crack of his death-dealing rifle added another victim to the price which he had placed upon his own life. Finally when fire and smoke became too much for flesh and blood to stand, the long sought for fugitive appeared in the door, rifle in hand, to charge the countless guns that were drawn upon him. With a courage which was indescribable, he raised his gun to fire again, but this time it failed, for 100 shots riddled his body, and he fell dead face front to the mob.26

The Robert Charles shooting is a dramatic episode within a broad practice of arms that included plenty of prosaic beneficial gun use as well as ordinary crime and stupidity. Textured renditions of those more pedestrian episodes are rare. But there is a good example in the account of young Louis Armstrong, who reveals a pivotal episode of stupidity with a gun within a subculture that seemed to have plenty of it.

Armstrong’s autobiography suggests that firearms were common among the denizens of black New Orleans at the turn of the century. Before he became the world-renowned horn player, Armstrong waded through the streets and dives of New Orleans and actually was set on his way to fame and fortune by a foolish act with a gun.

As a teenager, Armstrong, armed with a pistol, dived into a stupid contest of bravado that leaves one thinking sympathetically about modern stop-and frisk programs. Armstrong and his fledging musical troupe were roaming the streets, singing for money. According to Armstrong, it was common to celebrate the holidays by “shooting off guns and pistols or anything loud so as to make as much noise as possible.” So when he ventured out New Year’s Day, he took the .38 caliber revolver that his mother kept in a cedar chest. It was a common gun, the same type that Robert Charles had carried.

On Rampart Street, Armstrong’s little group passed by a kid who had made similar preparations. Armstrong was laughing and singing when “all of a sudden a guy on the opposite side of the street pulled out a little old six-shooter pistol and fired it off.” Armstrong’s friends goaded him, “Go get him, Dipper.” Armstrong pulled his gun “and let her go.” Armstrong’s gun was evidently a larger caliber. The noise and smoke frightened the other kid away, and Armstrong proceeded down Rampart Street, triumphant. He reloaded and started to shoot into the air again, when “a couple of strong arms came from behind” and dragged him off to jail.27

Armstrong’s recklessness earned him a stay in the Colored Waifs Home, where he picked up a cornet from a little shelf of cast-off instruments. Armstrong’s story ended well. Many Negroes who reached for a gun were not nearly so lucky. And it demonstrates the power of the self-defense impulse that a robust black tradition of arms developed in spite of the unpredictable and often-tragic results of owning and using guns.

Ida Wells surely wrestled with the worry that violence is an unpredictable catalyst.28 Although we have sparse good data on black gun crime at the turn of the century, we know that by 1920 the black homicide rate in many southern cities exceeded the exceptional murder rates of today’s black underclass. Anecdotal evidence suggests that this tracks earlier trends. Wells surely was aware of the ordinary interracial violence and common stupidity with guns illustrated by Louis Armstrong’s boyhood recklessness. Still, she erred toward folk having the option of armed self-defense, and that judgment was shared by prominent blacks of the day.

Having already lost so much politically, and pushed further by the horror of lynch law, blacks at the end of the nineteenth century were operating in perhaps the most desperate time of their American experience. And lest anyone think that things could get no worse, the United States Supreme Court would soon invite further indignities in The Civil Rights Cases, concluding that neither the Thirteenth nor the Fourteenth Amendment were sufficient authority to sustain the public accommodations sections of the Civil Rights Act. This gave a green light to the full array of Jim Crow Laws and demonstrated for many the need for a national civil-rights organization to defend black interests. It also underscored the importance of self-help on a number of measures, including personal security.29

No one was more animated on this point than the man who sheltered Ida Wells after she burned her bridges in Memphis, fiery editor of the New York Age, T. Thomas Fortune. Fortune was born a slave in Florida, in 1856. He came of age during Reconstruction and witnessed its promise and disappointment as his father Emanuel rose and fell in the tide of postwar politics. Like many blacks who staked their hopes on Reconstruction, Emanuel Fortune confronted white opposition united in its disdain for black rule—Whigs, Democrats, the landed rich, the rural poor, and the merchant class put aside their differences and coalesced around their common whiteness. Their opposition to Reconstruction was not just political but violent.30

A delegate to the 1868 Florida constitutional convention, Emanuel Fortune was a rising star among black Republicans. And that made him and his political friends targets of violence. Just after nightfall in 1869, one of Fortune’s cohorts, Freedman’s Bureau agent W. J. Purman, was shot from the shadows while walking across the town square. Purman limped to safety and managed to survive. In the days that followed, a group of armed black men paid him a discreet visit and pledged to sack the village if Purman gave the word. It is not clear if Emanuel Fortune was part of this group. But it is clear that Fortune was armed and prepared to fight.

Even before the shooting of W. J. Purman, Emanuel Fortune was wary of the mounting threats. Fearing ambush, he stopped traveling after nightfall, developed an enviable skill with a rifle, and made detailed preparations for any attack on his home. At the first hint of trouble, the children were to run upstairs. His wife, Sarah Jane, would then open the door and shield herself behind it. Emanuel, from the cover of a barricade he built in the center of the room, would open fire with his rifle.31

One longs for more on the effect that this planning had on young Timothy as he passed by the barricade every day, and played on and around the bulking reminder that any random night might bring a gunfight. So far as we can tell, Emanuel Fortune’s defensive plan was uncashed insurance, but the fighting spirit it reflected burned hot in his son Timothy.

Soon after the election of 1876 closed the door on Reconstruction, Timothy Thomas Fortune moved to New York, where he would eventually establish a newspaper that became the New York Age and later simply The Age. Fortune proved to be a kindred spirit for Ida Wells, at least for a time. He surrendered nothing to her in his militancy, and he endorsed armed self-defense just as fervently, although perhaps less colorfully.

T. Thomas Fortune and Ida Wells were part of a new generation of activists in the freedom struggle. Some of them started newspapers—men like Harry C. Smith, who established the Cleveland Gazette, and W. Calvin Chase, who started the Washington Bee. Others, like New York lawyer T. McCants Stewart, made their mark in the professions or in business. Richard T. Greener, the first black graduate of Harvard, characterized this new generation as “Young Africa, stronger in the pocket and mildly contemptuous of the lofty airs of the old decayed colored aristocracy.” These men and women channeled the voice of the “New Negro,” a rising class of black agitators who, Fortune asserted, were “the death knell of the shuffling, cringing creature in black who for two centuries and a half had given the right-of-way to white men.”32

Fortune was an articulate but volatile affiant of the black tradition of arms. Although he proposed to respect the line between political violence and self-defense, his passion fueled a rhetorical style that sometimes treaded close to the boundary. Describing the agenda and strategy of his proposed national civil-rights organization, the Afro-American League, Fortune exhorted, “we propose to accomplish our purposes by the peaceful methods and agitation through the ballot and the courts. But if others use the weapons of violence to combat our peaceful arguments, it is not for us to run away from violence. . . . Attucks, the black patriot—he was no coward! . . . Nat Turner—he was no coward! . . . If we have work to do, let us do it. And if there comes violence, let those who oppose our just cause ‘throw the first stone.’”33 Looking out desperately toward the new century, Fortune declared, “to be murdered by mobs is not to be endured without protest, and if violence must be met with violence, let it be met. If the white scamps lynch and shoot you, you have the right to do the same.”34

Some criticized him for agitating from the relative comfort and safety of New York City, but Fortune had endured his share of racism and did not shy from a fight. In fact, he seems consciously to have picked one in 1890 when he entered the bar at the Trainor Hotel on Thirty-Third Street and demanded a glass of beer. He was refused service, as he apparently expected. In the record from a subsequent trial, the bar owner claimed that Fortune threatened to “mop up the floor with anyone who laid hands on him.”

Fortune gave a different account of the conflict. He sued the bar owner for assault, solicited donations for a litigation fund, and ultimately won a thousand-dollar jury verdict. The black press celebrated Fortune’s victory. He was the model of the New Negro, said the Indianapolis Freeman, adding that in the past “the Negro’s greatest fault was being a magnificent sufferer.”35

The allegation that Fortune had threatened to mop up the floor with anyone who laid hands on him is consistent with his editorial stance. Denouncing a Georgia court decision allowing railroad conductors to send black first-class passengers back to the smoking car, Fortune advised Negroes to “knock down any fellow who attempts to enforce such a robbery.”

Cognizant that he was advising Negroes to strike the first blow, Fortune equivocated, “we do not counsel violence; we counsel manly retaliation.” Then, capturing the dilemma that state failure and malevolence posed for blacks, he reasoned, “in the absence of law . . . we maintain that the individual has every right in law and equity to use every means in his power to protect himself.”

Fortune’s militant stance extended explicitly to the use of firearms. Commenting on an interracial gunfight in Virginia, Fortune wrote, “if white men are determined upon shooting whenever they have a difference with a colored man, let the colored man be prepared to shoot also. . . . If it is necessary for colored men to arm themselves and become outlaws to assert their manhood and their citizenship, let them do it.”36

This editorial drew a harsh response from the white press. One paper argued that Fortune’s advice would provoke a race war that blacks could not win. Fortune responded with an essay titled “The Stand and Be Shot or Shoot and Stand Policy”: “We have no disposition to fan the coals of race discord,” Thomas explained, “but when colored men are assailed they have a perfect right to stand their ground. If they run away like cowards they will be regarded as inferior and worthy to be shot; but if they stand their ground manfully, and do their own a share of the shooting they will be respected and by doing so they will lessen the propensity of white roughs to incite to riot.” On the last passionate turn, Fortune argued that a man who would not defend himself was properly deemed “a coward worthy only of the contempt of brave men.”

Fortune’s prescription here teases back and forth into the boundary-land between political violence and individual self-defense. The editor of the Cincinnati Afro-American saw Fortune’s approach as utter folly and welcomed inclusion on “the list of cowards,” arguing that it was indeed “better for the colored man to stand and be shot than to shoot and stand.” This dissent provokes the question whether Fortune was on the edge of community sentiment or in the middle of it.

One signal of how Fortune’s views resonated in the community is the long-standing but largely secretive connection between him and the conservative Booker T. Washington. In a decades-long relationship, Fortune was sometimes a daily correspondent with Washington and often served as ghostwriter for Washington’s books, speeches, and editorials. Washington secretly financed Fortune’s journalistic efforts, and when the New York Age was incorporated, Washington took a block of stock in exchange for his past and future support of the paper.

Fortune was a passionate race man and sometimes, especially in extemporaneous speeches, he projected a militant tone that the Wizard of Tuskegee surely deemed unwise. This was certainly the case in 1898 when an irate Fortune unleashed a tirade against President William McKinley’s tour of reconciliation through the South. Incensed that McKinley was honoring Confederate dead while blacks were being lynched in the name of white supremacy, Fortune ranted, “I want the man whom I fought for to fight for me, and if he don’t I feel like stabbing him.”37

Later Fortune said that he had not advocated “physical assassination” but rather meant to stab McKinley at the ballot box. Still, his comments were widely criticized, and Booker T. Washington surely was not happy with the attack on the Republican president, who still held more promise for blacks than the Democrat alternative.38

We are left just to wonder about the conversations Washington and Fortune had on questions of defensive violence. When Washington died, his people scurried to retrieve their correspondence. But we know for sure that Washington was a gun owner. In 1915, the Tuskegee faculty presented the aging headmaster with a shotgun as a token of their affection. One of his biographers says that the gift reflected the faculty’s desire that the aging and overworked Washington get some rest and recreation. But it also suggests Washington was familiar with firearms and reflects the prosaic nature of gun ownership in the culture of Tuskegee.39

Booker T. Washington’s support of T. Thomas Fortune overlapped with a variety of controversial statements. At a speech at the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church in Washington, DC, Fortune boiled over at reports from a recent conference, where prominent white university professors, ex-governors, and presidential cabinet members opined on the state of the Negro postemancipation. Several of them had seriously proposed repealing the Fifteenth Amendment, which guaranteed black male suffrage. Here Fortune saw no need to dance around the edges of political violence. He threatened that the same amount of blood that had secured the Fifteenth Amendment would be required to revoke it. He advised black folk, “if the law can afford no protection, then we should protect ourselves, and if need be, die in defense of our rights as citizens. The Negro can’t win through cowardice.”

The white press criticized that Fortune’s prescription was folly “verge[ing] on crime.” But Fortune put the question in terms of essential manhood and whether some versions of life are worse than death.

The black man’s right of self-defense is identically the same as the white man’s right of self-defense. Tell me that I shall be exterminated, as you do, if I exercise that right and I will tell you to go ahead and exterminate—if you can. That is a game that two can always play at. And suppose you do exterminate me, what of it? Am I not nobler and happier exterminated while contending for my honest rights than living a low cur that any poor white sneak would feel free to kick?40

Fortune’s passion spilled over again at a Philadelphia meeting of the Afro-American Press Association. Motivated by a new spate of lynchings, Fortune raged, “we have cringed and crawled long enough. I don’t want anymore ‘good niggers.’ I want ‘bad niggers.’ It’s the bad ‘nigger’ with the Winchester who can defend his home and children and wife.” Fortune was followed by W. A. Pledger, editor of the Atlanta Age, who invoked the Winchester as the optimal tool against the mob.41

Fortune’s response to turn-of-the-century rioting in Atlanta that destroyed neighborhoods and killed scores of blacks was unsurprising. “The trouble will go on in Atlanta,” he said, “until the Negro retaliates—until driven to bay, the Negro slays his assailant.” In correspondence with Emmett Scott, chief aid to Booker T. Washington, Fortune seethed, “What an awful condition we have in Atlanta. It makes my blood boil. I would like to be there with a good force of our men to help make Rome howl.” Fortune dismissed “nonresistance,” arguing to Scott that incidents like the Atlanta riot invited “contempt and massacre of the race.”42

Fortune offered a series of episodes as models for black self-defense, including, prominently, an 1888 incident in Mississippi. It started with a black man’s refusal to step aside for white people on the sidewalk and escalated into a nasty scrap. When the talk turned to lynching, the black men of the community grabbed their guns, laid an ambush, and, on Fortune’s telling, fired on the “lynching party of white rascals, killing a few of them.” Fortune excoriated the northern white press for casting the blame on the black men.

Fortune saw this incident as a model of black resistance, arguing that if whites “resort to the gun and the torch . . . let the colored men do the same, and if blood must flow like water and bonfires be made of valuable property, so be it all around, for what is fair for the white man to do to teach the Negro his place is fair for the Negro to do to teach the white man his place.”43

There is some instinct to dismiss Fortune’s rhetoric as a fringe voice in a sea of more levelheaded, nonviolent folk. But that dissolves under the assessment of Kelly Miller, dean of Howard University, who wrote in the Amsterdam News that Fortune “represented the best developed journalist that the Negro race has produced in the Western world. His editorials were accepted throughout the journalistic world as the voice of the Negro. Between the decline of Frederick Douglass and the rise of Booker T. Washington, Fortune was the most influential Negro in the country.”44

There are many confirmations that Fortune was channeling community attitudes about armed self-defense. It is evident in the black reaction to the 1898 coup that extinguished Negro influence in Wilmington, North Carolina. Wilmington had a black voting majority and numerous black officeholders supported by a fusion ticket of populists and Republicans. Republicans controlled the board of aldermen, where three black members served. Blacks served prominently in the local judiciary, and black postmasters numbered more than twenty. All of this rested on a thriving black middle class of hoteliers, merchants, druggists, bakers, and grocers.

This success bred tensions, and things boiled over when Alex Manly, editor of the black newspaper the Daily Record, launched his own attack against the rape justification for lynching, arguing, “every Negro lynched is called a big burly black brute, when in fact, many of those who have thus been dealt with had white men for their fathers, and were not only not black and burly, but were sufficiently attractive for white girls of culture and refinement to fall in love with, as is very well known to all.” Manly was doubly offensive as the embodiment of his own critique. He was the acknowledged mulatto son of former North Carolina governor Charles Manly.

These accumulated affronts drove Democrats over the edge. Backed by Klan-type organizations dubbed “Red Shirts” and “Rough Riders,” Democrats summoned thirty-two of the city’s prominent blacks and laid out their demands: All black officeholders in Wilmington must resign and Alex Manly must leave Wilmington.

Then, while the black elite were formulating a response, the Democrats launched a wave of violence that steamrolled the scattered Negro opposition. The Republican-Populist administration was ousted and replaced with Democrats. More than 1,400 blacks abandoned their property and fled the city. One commentator called it “the nation’s first full-fledged coup d’état.”45

Across the country, black reaction to the coup was visceral. A protest rally at the Fifth Avenue Baptist Church in Washington, DC, is emblematic. To a chorus of sympathetic cheers and angry tears, Colonel Perry Carson raged against the coup in Wilmington and lamented the lack of preparedness. Wilmington, he said, was an object lesson that blacks must, “prepare to protect yourselves; the virtues of your women and your property. Get your powder and your shot and your pistol.” The Washington Post was apoplectic, not so much about the Wilmington coup, but that a previously sensible colored man like Carson was urging Negroes to arms.46

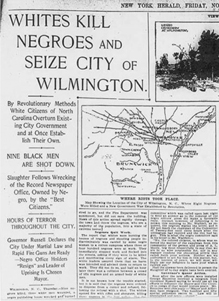

Fig. 4.1. Newspaper coverage of the Wilmington race riots. (New York Herald, Friday, November 10, 1898.)

Lesser incidents provoked similar responses in the black press and even among the clergy, who extolled the self-defense impulse even where there was little hope of prevailing. In the Cleveland Gazette, Reverend C. O. Benjamin celebrated the heroism of a black man in Mississippi who resisted his white assailants, urging that “Negroes should stand like men.”47 Speaking before the Afro-American Press Association in 1901, W. A. Pledger of the Atlanta Age similarly advised that terrorists “are afraid to lynch us where they know the black man is standing behind the door with a Winchester.”48

Pressing against the boundary of political violence, Bishop Alexander Walters of the AME Zion Church urged development of a national black organization with an explicit focus on community self-defense. In a March 10, 1898, letter in the New York Age, Walters exhorted, “after the late outrages perpetrated against postmasters Loften of Hogansville, Georgia, and Lake of Lake City, South Carolina, for no other reason than their race and color . . . it becomes absolutely necessary that we organize for self-protection.”49

After the torture and burning at the stake of Sam Hose in 1899, with its incomprehensible carnival atmosphere, Walters was moved beyond restraint and openly advocated political violence. In an address to the New Jersey Methodist Conference, Walters juxtaposed the recent American bloodshed to “free” Cubans and Filipinos from Spanish domination, with the barbarism of the southern lynch mob. “The greatest problem of America today,” said Walters, “is not the currency question nor the colonial processions, but how to avoid the racial war at home. You cannot forever keep the Negro out of his rights. Slavery made a coward of him for 250 years, he was taught to fear the white man. He is rapidly emerging from such slavish fear and ere long will contend for his rights as bravely as any other man. In the name of the Almighty God, what are we to do but fight and die?”

When Bishop Walters’s first concrete action after the Sam Hose lynching was to call for a day of prayer and fasting, W. Calvin Chase saw it as a retreat and criticized that it would have no impact on “cutthroats, lynchers and murderers.” Chase said that blacks were “praying when they needed to strike.” Julius F. Taylor, editor of the Salt Lake Broad Axe, affirmed this sentiment, urging that “the Negro must not expect to have his wrongs righted by praying, fasting and singing, but he must rely on his own strong arm to accomplish that objective.”50

Although he may have been short on follow-through, Bishop Walters’s statements are significant as a suggestion of how self-defense resonated within the community. And it speaks to the power of the self-defense impulse that, even within the black clergy, he was not alone. In 1897, following the lynching of two men in Louisiana, AME bishop Henry McNeal Turner wrote in the Voice of the Missions newspaper that Negroes should defend themselves with guns against the lynch mob. He urged blacks to acquire guns and “keep them loaded and ready for immediate use.” Turner admitted that his views might be considered an unseemly departure for a man of God and that he had held his tongue for many years, out of concern for the religious organization he represented. But after the latest lynchings, he was now urging, “Get guns Negroes, get guns, and may God give you good aim when you shoot.”51

This sentiment was shared by emerging black intellectual John Edward Bruce, lecturer, editor, self-taught historian, and founder of the Negro Society for Historical Research. Bruce reserved nothing in his condemnation of lynch violence. His October 5, 1889, speech in Washington, DC, urging violence in kind against the mob, is representative. “The man who will not fight for the protection of his wife and children,” said Bruce, “is a coward and deserves to be so treated. The man who takes his life in his hand and stands up for what he knows to be right will always command the respect of his enemy.” Bruce seemed unconcerned about treading over into advocacy of political violence:

Let the Negro require at the hands of every white murder in the South or elsewhere a life for a life. If they burn your houses, burn theirs. If they kill your wives and children, kill theirs. Pursue them relentlessly. Meet force with force, everywhere it is offered. If they demand blood, exchange with them until they are satiated. By vigorous adherence to this course, the shedding of human blood by white men will soon become a thing of the past. Wherever and whenever the Negro shows himself to be a man he can always command the respect even of a cutthroat. Organized resistance to organized resistance is the best remedy for the solution of the vexed problem of the century which to me seems practical and feasible.52

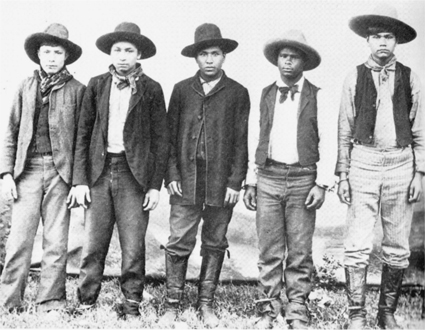

Fig. 4.2. Negro leaders of the late nineteenth century, Frederick Douglass (center), T. Thomas Fortune (upper left), Booker T. Washington (upper right), Garland Penn (lower left), and Ida B. Wells (lower right), circa 1900. (Courtesy of the New York Public Library; Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture; Manuscripts, Archives, and Rare Books Division.)

Publisher and philanthropist Mrs. C. C. Steward urged that black folk take a lesson from their white neighbors, “The white man knows how to shoot and keeps his Winchesters. He teaches his wife and his baby boy to shoot.” This was a lesson, said Steward, that “the Negro needs to learn. . . . A good double barrel rifle and plenty of ammunition will go a great deal further in protecting our families from being mobbed and lynched than all the prayers which can be sent up to heaven.”

Considered against the sentiments of his peers, T. Thomas Fortune’s views about armed self-defense were not at all unusual. And he did not build one of the highest-circulating Negro papers in the country by being out of step with the mood of black folk. On the theme of self-defense, Fortune’s exhortations were not some tough medicine he was pushing onto the masses. He was channeling the sentiment of the community.

This sentiment was fueled in part by the failure of government at all levels to protect and serve black folk, a failure that drove calls for an array of black self-help strategies and spurred the development of national civil-rights organizations that Fortune and Ida B. Wells would help start. Fortune despaired at the lack of grassroots financial support for the Afro-American League, the organization he conceived in 1886. It would never really thrive, but the pulse of the league fueled development of the Afro American Council, the Committee of Twelve, the Niagara Movement, and ultimately the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.53

With federal abandonment of Reconstruction, rising lynch violence, and disenfranchisement of black voters, the outlook for blacks in the late nineteenth century seemed so dim that many Negroes thought the best thing to do was to leave. The grand schemes to settle in Liberia or the Caribbean are familiar. But there were also small-scale movements within regions.

In some cases, Negroes fled to urban centers, spurred by violence in the countryside. But there was also an impulse in the other direction. Following race riots in the urban North, Henry Highland Garnet advised flight to the countryside, complaining that “prejudice is so strong in cities, and custom is so set and determined, that it is impossible for us to emerge from the most laborious and the least profitable occupations. . . . For instance in the city of New York, a colored citizen cannot obtain a license to drive a cart! Many such inconveniences beset them on every hand.”

Garnet surely idealized the countryside. But he was driven by an impulse familiar to many Negroes that there must be someplace better than where they were. And that impulse drove many black folk to strike out for the American West.54

The story of Negroes in the West is obscured by the dominant narrative of the white cowboy. Some research traces this tilt to the class and racial bias of Owen Wister, whose classic novel The Virginian in many ways frames the canon that feeds the popular narrative and drives much of the American mythology of the gun. But the reality was far richer than the myth. The real American West was not the lily-white scene portrayed in film but a far more racially mixed affair that contributes abundantly to the black tradition of arms.55

By 1870, roughly 284,000 blacks accounted for 12 percent of the population of sixteen Western states and territories. But Negroes actually show up as early as 1790, in a Spanish census, where roughly 20 percent of the populations of San Francisco, San Jose, Santa Barbara, and Monterey acknowledged African ancestry. Until the United States’ conquest of the Mexican territory, about 15 percent of Californians continued to acknowledge African heritage. But with the coming of US rule, the incentive to deny Negro blood resulted in the large-scale “disappearance” of that population. These largely mixed-race people were still there, of course. But now they had stronger reasons to disclaim their African roots.56

The most obvious prewar path west for blacks was slavery. One underacknowledged aspect of this movement is the population that went west as slaves of Indians who were displaced from the southeast under the Indian Removal Act of 1830. Among the Five Civilized Tribes forced from the East, only the Seminoles of Florida abjured slavery and actually developed alliances and friendships with blacks in two separate waves of interaction.

As early as the 1690s, Spain tempted slaves from the English colonies into Florida with the promise of freedom under Spanish rule. In 1739, an African named Francisco Menendez actually commanded the stronghold at Fort Mose, with the assignment of protecting St. Augustine from attack. In 1740, his forces helped repel an English attack led by Georgia governor James Oglethorpe.

By the 1780s, Florida was home to Spanish-speaking Africans, fugitive slaves from the colonies, and indigenous and migrated Indian tribes, including the Seminoles. Fugitive slaves established maroon settlements in Spanish Florida with names like “Disturb Me If You Dare” and “Try Me If You Be Men.” By 1819, when the United States purchased Florida from Spain, General Andrew Jackson commented that the transaction had finally closed “this perpetual harbor for our slaves.”

Equally instructive is the 1837 assessment of the Second Seminole War by Major General Thomas Sidney Jessup: “This you may be assured, is a Negro, not an Indian war; and if it be not speedily put down, the South will feel the effects of it on their slave population before the end of the next season.” Modern research echoes this view, concluding that the Second Seminole War is better described “as a Negro insurrection with Indian support.”57

Fig. 4.3. Escape into the Swamps. (Drawing by B. West Clinedinst, from Harriet Beecher Stowe, The Writings of Harriet Beecher Stowe [Houghton, Mifflin/Riverside Press, 1896].)

When the Five Nations were driven west under the 1830 Indian Removal Act, the four slave-owning tribes (Choctaw, Chickasaw, Cherokee, and Creek) took their Negro slaves with them. Wealthier members owned enough Negroes to constitute up to 15 percent of the tribal populations. Settling in newly designated Indian Territory (much of modern-day Oklahoma), they continued to hold and acquire slaves with the encouragement of Indian agents in the employ of the United States government.58

Negroes enslaved by Indians were generally better treated than the slaves of whites, a trend that caused one Indian agent to recommend bringing in white men to show how American slavery was supposed to be done. Still, the impulse to resist slavery generated breaks for freedom, and slaves sometimes deployed firearms in the attempt.

In November 1842, a group of Negroes in Weber Falls, Indian Territory, seized guns, horses, and supplies and fled to Mexico. Some suspected that Seminoles had incited the revolt. The fugitives were pursued by their Cherokee masters and fought them off in a two-day gun battle. Finally, Cherokee reinforcements subdued the runaways and returned them to punishments of whipping and hanging.59 In other parts of Indian Territory, the population of runaway slaves was substantial enough to produce robust fugitive communities. One group of about two hundred built a fort on the Washita River and was blamed for raids and killings in the area for more than a decade.

Indian Territory would be surrounded by the Confederacy, and the Five Civilized Tribes aligned with the South during the Civil War. Tribal slaves freed after the Civil War accounted for one strand of the black population in the west, although, in a curious detail, slavery in Indian Territory was not dissolved by the Thirteenth Amendment in 1865 but by treaty in 1866.

Within the Indian nations, blacks fought for equal rights in a fashion that resembled the broader national struggle. But black Indians also acknowledged an advantage to living under the jurisdiction of the Indian Nations versus the United States. Black Indian leader O. S. Fox reminded his friends that “the opportunities for our people in that country far surpassed any of the kind possessed by our people in the U.S.”

When the federal government divided tribal lands among individuals in the 1880s, freedmen of Indian masters were treated like members of the tribe and received homesteads of eighty-eight acres. While in the rest of United States, the final decades of the nineteenth century was one of the lowest points of the black American experience, in 1884, the Indian Nations were arguing the question of full equality for black members.60

The appetite for western expansion eventually consumed large parts of Indian Territory. In 1889, the federal government forced Indian tribes to surrender their land in exchange for cash and sparked the rush of homesteaders into Oklahoma Territory. Among those who lined up to claim their portion, approximately ten thousand were Negroes. The black Indians already in the territory dubbed these newcomers “State Negroes.”

For blacks from the east, the promise of free land was an opportunity to build an independent black society. One of the most ambitious promoters of this movement was Edwin P. McCabe. McCabe had the grand vision of transforming the Oklahoma Territory into a black state where he would serve as governor. Toward that dream, McCabe founded the town of Langston, which seeded twenty-seven other black towns in the territory.

McCabe’s ambitions were ill received by whites. An 1890 article from the Kansas City News reports that whites “almost foam at the mouth whenever McCabe’s name is suggested for Governor [and] also at the idea of Negroes getting control.” A concurrent New York Times report speculated that McCabe might soon be assassinated.

McCabe and his community appreciated the hazards. The threat was palpable in September 1891, as the Sac and Fox Indian reservations were scheduled to open for settlement. McCabe had been coaxing blacks for more than a year to come and claim their share of the bounty. He also was candid about the challenges.

Blacks had been run out of several other staging towns. But in Langston City, more than two thousand armed Negroes assembled in preparation for the land rush. After sporadic bouts of gunfire, McCabe himself was accosted and fired on by three white men. He was rescued by a group of friends wielding Winchester rifles. It was exactly the kind of scenario that prompted Ida B. Wells to advocate a Winchester in every Negro home. And within seven months of Negroes wielding Winchesters in defense of Edwin McCabe, Wells would walk among them in Oklahoma.61

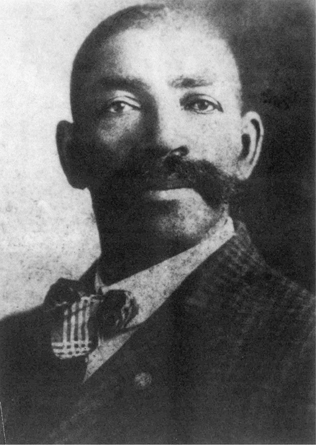

Fig. 4.4. Portrait of Edwin McCabe.

After the Tom Moss lynching, the Langston City Herald solicited blacks in Memphis, urging that it “would be a good place for the colored people to leave.” Some claimed that Tom Moss spent his last breath urging Negroes to abandon Memphis and head west. Exiled in New York, Ida B. Wells put a sharp point on the assessment of those in the Memphis emigration movement. “Many of our exchanges have been calling Memphis hell, without stopping to think they were doing the real hell an injustice. Hell . . . is a place of punishment for the wicked—Memphis is a place of punishment for the good, brave and enterprising.”

Wells was serious about the prospect of western migration, but she was also cautious about endorsing a place she had never seen. In 1882, she undertook a fact-finding mission, traveling as a guest of her cousin’s husband, I. F. Norris. Norris was an emigration agent paid to promote black settlement in Oklahoma. He arranged for Wells to see for herself whether Oklahoma was a promising destination for Negroes. Wells arrived in Oklahoma in April and spent three weeks there. She had meetings with the Langston City Herald, and it would be surprising if she did not discuss the recent attack on Edwin McCabe and his rescue by black men with Winchesters.62

Wells took the dignitary’s tour, traveling from Langston City to the territorial capital of Guthrie, to Oklahoma City, and to the town of King Fisher. Along the way, she was encouraged to see black councilmen, constables, and school committees. But Wells also detected a clear sentiment of opposition to the “Africanizing” of Oklahoma manifested by multilayered threats.

Simmering hostilities in the town of King Fisher confirmed the wisdom of Wells’s views about armed self-defense, and the black men of King Fisher were precisely in accord with Wells. They formed a squad of men armed with Winchester rifles and threatened to sack the town if anyone in their community was harmed. A traveling journalist observed, “the colored men in Oklahoma mean business. . . . They have an exalted idea of their own rights and liberties and they dare to maintain them. . . . I found in nearly every cabin visited a modern Winchester oiled and ready for use.”63

Wells’s final assessment of the Oklahoma Territory was skeptical. She might have been encouraged by the fact that a justifiable shooting of a white man by a Negro, like the incident in the black town of Boley, could conclude without a lynching. But she saw insufficient employment opportunities to support “an indiscriminate exodus of our people.” And she probably was right about the inability of the territory to absorb a mass of blacks looking for jobs and neighborhoods like they would leave in Memphis. Still, folk came.64

The black towns in Indian Territory are only one aspect of the rich black presence in the west. Even among the solitary mountain men and trappers who operated on the edge of the frontier, Negroes carved their place. Notable among them was Jim Beckwith, son of a white man and a slave woman. Beckwith trapped beaver, survived gunfights, and lived and finally died among the Crow Indians. But for the happenstance of telling his story to a traveling reporter, Beckwith and his exploits would be lost to us. And while the number of these black mountain men cannot be determined for certain, it is clear that Beckwith was not unique. Witness Edward Rose, who appears in a broader treatment of the western mountain men of the 1830s. His reported exploits with the gun satisfy every western stereotype.65

Frontier-era conflicts along the color line become blurred and complicated as red, black, and white men mixed together in various contexts. A typical pathway for blacks into Texas was as slaves to migrating whites. These Negroes sometimes found themselves fighting Indian raiding parties that had attacked their white masters. In other situations, blacks actually joined with Indians in renegade raiding parties like the ones that attacked the Hoover family in 1861 and Texas rancher George Hazlewood in 1868. In some cases, Negroes were actually on both sides of the conflict, as in 1869 when a group of Indian fighters led by a black man attacked a dozen cowboys, killing three of them and wounding five others. They were finally run off by gunfire from a rescue party headed by a Negro cowboy.

In 1845, when Texas entered the union, it had about 100,000 white settlers and 35,000 slaves. By 1861, the slave population had grown to about 182,000. The promise of freedom in Mexico was a particular draw for slaves along the southern border. An 1845 report from Houston illustrates the character of that resistance. According to the Houston Telegraph, a group of twenty-five Negroes escaped from Bastrop, “mounted on some of the best horses that could be found, and several of them were well armed. It is supposed that some Mexican . . . enticed them to flee to the Mexican settlements West of the Rio Grande.”66

The draw to Mexico was strong enough that in 1854, the Austin State Times reported that more than 200,000 slaves had escaped to Mexico. This estimate is fantastically exaggerated (the 1860 census reported 182,556 slaves in Texas). But it does show that slave escapes into Mexico were a pressing concern. A more realistic estimate of Texas fugitives appears in the complaint of southwest Texas slave owners that more than four thousand fugitive Negroes were living across the border.67

The worry about Mexico as a growing haven for fugitives boiled over in 1855. A border settlement of Indians and fugitive Negroes led by a chief named Wildcat had been a particular lure for Texas slaves. The settlement was such a draw for runaways that south Texas slaveholders raised $20,000 for a punitive expedition against it. In 1855, one hundred thirty Texans led by a captain of the Texas Rangers rode across the border to break up the settlement and retrieve fugitive slaves. They were repelled by a superior force of Negroes, Indians, and Mexicans who were waiting in ambush. Roundly whipped, they fled back across the border carrying their wounded and some baubles from the little town of Piedras Negras that they looted on the way out.68

Presidents James Polk and Zachary Taylor both pressed Mexico to return fugitive slaves to their owners. The precise Mexican reply, that “no foreign government would be allowed to touch a slave who had sought refuge in Mexico,” probably never filtered down to the average Texas slave. But there was plainly an appreciation among Negroes that freedom lay south. This was the draw for a slave girl named Rachel who, along with two others, stole guns and fled across the border. A slave named Bill followed the same script. The “bright mulatto . . . knocked down his overseer and ran off with a double barrel shotgun.”69

Although dwarfed by the population of slaves, free blacks pursued their own opportunities in the prewar west. A rare and striking case is the Ashworth family, which in 1850 owned two thousand acres of land, more than five thousand head of cattle, and at least a dozen slaves. In a swirl of jealousy, ambition, and tribalism, they tumbled to the center of what came to be known as the Orange County War.

Originally from Louisiana, the Ashworths settled around the east Texas town of Madison (now Orange) in the early 1830s. Census records show four brothers and their families. There is some dispute about whether they fought for the Republic of Texas in its war of independence from Mexico. At least two of them sent substitutes.70

Technically the Ashworths were mixed-race people. At least one of the brothers was reportedly married to a white woman, although the distinction between them would have been difficult to discern just by looking. But the Ashworth’s African lineage was sufficiently recorded that it took an act of the Texas Congress in 1840 to exempt them from legislation requiring free blacks to leave the republic.

This was quite a political feat for any Negro in the nineteenth century, and it reflected the bonds of business, family, and friendship that the Ashworths had built among the whites of east Texas. This included the county sheriff who, through business interests or some vague family connection, was a staunch ally of the Ashworths’.71