“I bought a Winchester double-barreled shotgun and two dozen rounds of shells filled with buckshot. If a white mob had stepped on the campus where I lived I would without hesitation have sprayed their guts over the grass.”1

Guts sprayed over the grass? Who would think such a thing, let alone say it? When we learn that it was the stiff-collared, Harvard PhD W. E. B. Du Bois, perhaps still the preeminent intellectual of the race, the black tradition of arms gains new resonance.

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois was born into the relatively benign environment of Berkshire County, Massachusetts. His people had lived free there since the eighteenth century. An acknowledged prodigy, Du Bois demonstrated his gifts early in competitions with white classmates and eased gently into the cauldron of American racism when a little white girl nastily refused his offering in the school’s visiting-card exchange.

Du Bois would become the leading voice for the higher aspirations of black folk, famously warring with Booker T. Washington’s strategy of uplift through industrial education. His energy and vision were a crucial force in the early development of the NAACP. Through the association’s flagship magazine, The Crisis, Du Bois spoke to and for the American Negro like no one else on the scene. A Pulitzer Prize–winning treatment of his life is aptly subtitled Biography of a Race.2

By 1906 Du Bois was ensconced as professor of economics and history at Atlanta University, one of the top Negro schools in the country. His shotgun threat was a response to the carnage of the 1906 Atlanta race riot. The riot was a piece with the times. The immediate catalyst was the claim of assaults by black men on white women. The local press fanned the flames with special editions carrying at least two specious reports of such attacks. These allegations caught hold in the context of widespread white angst about the real and imagined debaucheries of Atlanta’s “Decatur Street Dives” and the black criminality that their patrons represented.3

This was a period in America where Negroes were regularly lynched. The Fulton County, Georgia sheriff’s spitting public assessment reflected the times: “Gentlemen we will suppress these great indignities upon our fair wives and daughters if we have to kill every Negro in a thousand miles of this place.”4

By arming himself in Atlanta, Du Bois was something of an aberration, but only in the sense that he was late to the game. Many in his circle owned and carried guns, but he never had. As a freshman at Fisk University in 1886, Du Bois recorded that his classmates commonly carried guns whenever they ventured into Nashville.5 He was lucky that he was able to find a shotgun for sale and had the money to buy it when the Atlanta rioting broke out.6

While no one of note appreciated it at the time, the Atlanta riot also was a formative experience for a young man who would become Du Bois’s comrade in arms, young Walter White, later the famous spokesman for the NAACP. With a mob advancing, thirteen-year-old Walter waited with his father, gun in hand, at the front windows of their Huston Street home. Shooting from a nearby building repelled the mob before he was forced to fire. But the episode seared in White’s memory and cemented his Negro identity.7

Walter White’s time would come. But Du Bois was already in the thick of the dilemma that burdened blacks trying to navigate the political disenfranchisement and the private violence of early twentieth-century America. With the lessons of Confederate redemption still vivid, the folly of political violence was evident. But the draw of self-defense against personal threats remained powerful.

The circumstances that sent Du Bois running for a gun held lessons about the danger of armed self-defense spiraling into political violence. Reaction to the riot from outside Atlanta made the boundary against political violence seem quite tenuous. Although Booker T. Washington, ever cautious in his public statements, vaguely urged “the best people” white and black to come together to prevent such episodes of disorder, many folk embraced the more militant thinking that fueled Du Bois’s armed stand.8 Among the rising national organizations, the Afro American Council, the Niagara Movement, and the Constitution League, the reaction was openly militant. At a meeting of the Afro American Council in New York, Dr. William Hunter raised the roof with a speech urging blacks to prepare for self-defense on a national scale, “not with brickbats and fire sticks but with hot lead.” To the issue of Negroes chafing under the malevolent authority of officials like the Fulton County sheriff, he advised, “Die outside of jail and do not go by yourself.”

Reverend George Lee of the Vermont Avenue Baptist Church in Washington, DC, cast off the restraints of his guild, declaring that the attacks in Atlanta dissolved any obligation of turning the other cheek. “I preached peace after the Atlanta riots,” said Lee, “But don’t misunderstand me, it was prudence, not my religion. If I had the power to stop that kind of thing, even by force, I’d use it. The trouble is all one-sided now, [but] trouble never stays one-sided for long. There’s going to be trouble on the other side soon.” The New York Times caricatured this militant chorus, but still captured the general sentiment with the headline “Talk of War on Whites at Negro Conference.”9

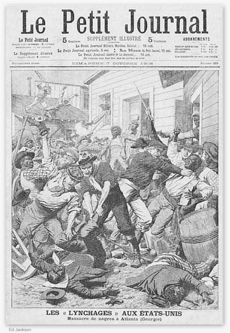

Fig. 5.1. The front cover of Le Petit Journal, covering the 1906 Atlanta riot. (Le Petit Journal, October 7, 1906, “The Lynchings in the United States: The Massacre of Negroes in Atlanta.”)

The ostensible militancy of the emerging leadership class was rooted in candid acknowledgement of daily threats and hazards. Most would reject political violence as strategically foolish. But it was hard to deny that arms for self-defense were a crucial private resource for blacks.

Du Bois projected this dichotomy in various ways. In his classic work, The Souls of Black Folk, Du Bois argued that organized violence was folly, noting that “the death of Denmark Vesey and Nat Turner proved long since to the Negro the present hopelessness of physical defense.” At the same time, in the chapter titled “Of the Coming of John,” a tale of violence and private honor, Du Bois championed self-defense as a core private interest.10

Responding to real-world threats, Du Bois was adamant about the legitimacy and perhaps the duty of self-defense, even where there was danger of spillover into political violence. Consider his 1916 editorial in the Crisis excoriating Negroes in Florida who submitted without resistance to the depredations of a lynch mob.

No colored man can read an account of the recent lynching at Gainesville, Fla., without being ashamed of his people. . . . Without resistance they let a white mob whom they outnumbered two to one, torture, harry and murder their women, shoot down innocent men entirely unconnected with the alleged crime, and finally to cap the climax, they caught and surrendered the wretched man whose attempted arrest caused the difficulty.

No people who behave with the absolute cowardice shown by these colored people can hope to have the sympathy or help of civilized folk. . . . In the last analysis lynching of Negroes is going to stop in the South when the cowardly mob is faced by effective guns in the hands of people determined to sell their souls dearly.11

In another Crisis editorial, following the 1919 Chicago race riot, Du Bois sharpened the point, pushing the boundaries of legitimate self-defense but still warning against violence as a political strategy.

Today we raise the terrible weapon of Self-Defense. When the murderer comes, he shall no longer strike us in the back. When the armed lynchers gather, we too must gather armed. When the mob moves, we propose to meet it with bricks and clubs and guns. But we must tread here with solemn caution. We must never let justifiable self-defense against individuals become blind and lawless offense against all white folk. We must not seek reform by violence.12

Du Bois nurtured the Crisis from its inaugural issue into the conscience, ambition, and voice of black America. It circulated far beyond its subscription base, passed from hand to hand and left in barbershops, in beauty salons, and on church pews. The Crisis offered a deeply textured critique of Negro life, carrying news ignored by the white press. It was superior to most of the black dailies partly because it was a periodical, which allowed more time to perfect the product. But the bigger difference was Du Bois.

The Crisis recorded the common news, culture, and hazards that fueled Du Bois’s stance on armed self-defense. There were many contributions by talented guests, but it is doubtful that anything appeared in the Crisis that Du Bois did not scrutinize. There were uplifting segments titled Industry, Education, and Social Progress. Other more somber sections like Crime, The Ghetto, and Lynching chronicled the indignities and threats that drove countless decisions by black folk to keep and carry firearms and the many episodes where Negroes fired guns in self-defense. Many of these probably were written by Du Bois, and a sampling of them helps us understand his stance on personal and political violence and the line between them.

These examples demonstrate the stream of incidents that Du Bois distilled for reporting to the national community. They put his thinking and writing about armed self-defense in context. And they demonstrate how odd it would have been if he had taken a more pacifist view.

Du Bois was not alone. The Crisis included contributions from many other talented folk. Writing in 1921, Mordecia Johnson was unapologetic about black resistance against the backdrop of abandoned Reconstruction and the violent triumph of Confederate redemption. “The swift succession and frank brutality of all this was more than the Negro people could bear. Their simple faith and hope broke down. Multitudes took weapons in their hands and fought back violence with bloody resistance. If we must die, they said, it is well that we die fighting. And the American Negro world looking on their deed with no light of hope to see by, said it is self-defense; it is the law of nature, of man, of God, and it is well.” 26

In 1918, Walter White, future executive secretary of the NAACP, reported on a series of lynchings in Georgia precipitated by the revenge shooting of a white planter, Hampton Smith. Smith was notorious for mistreating blacks, and most would not freely work for him. This sent him dredging the convict labor system for men who could not pay their fines, and thus could be “bought” for however long it took to work off the debt. Hampton Smith used this system to “buy” a Negro named Sydney Johnson. After Johnson had worked off his debt with some excess, he demanded payment for the additional time and then refused to work further. Smith responded by coming to Johnson’s home and beating him. As they parted, Johnson reportedly threatened Smith. Within a few days, Smith was dead, shot twice as he was sitting near the window in his parlor.

The reflex was vicious. Over a period of seven days, white mobs lynched at least four men and one woman (the eight-months-pregnant wife of one of the initial victims who dared to complain about the injustice and whose killing was so gruesome that one cannot bear to repeat the details). Johnson was finally cornered in Valdosta, armed with a shotgun and a revolver. He wounded two of his pursuers before dying in a hail of rifle fire.27

A 1921 editorial reporting on the NAACP’s twelfth annual conference exhibits familiar reverence for self-defense along with a caution against political violence: “Lynching and mob violence against Negroes still loom as our most indefensible national crime. Increasingly the Negro . . . has been forced to give his life in self-defense. No man can do less for his family and people and it is a cruel campaign of lying that represents this fight for life as organized aggression. Negroes are not fools. Eleven million poor laborers do not seek war on 100 million powerful neighbors. But they cannot and will not die without raising a hand when the nation lets its offscourings and bandits insult, harry, loot and kill them.”28 In the same volume, under his own byline, Du Bois asked facetiously, “Why is it that only Negroes must be meek and wait and wait! Why is it that only Negroes should not organize for self-defense against mobs?”29

Reports and editorials from the Crisis show that armed self-defense, though no guarantee of success, was considered a vital resource for blacks. It was an important component of the broader program for Negro advancement that Du Bois expressed this way in 1921:

The migration of Negroes from South to North continues and ought to continue. The North is no paradise. . . . But the South is at best a system of caste and insult and at worst a hell. With ghastly and persistent regularity, the lynching of Negroes in the South continues—every year, every month, every day; . . . the outbreaks occurring daily . . . reveal the . . . determination to keep Negroes as near slavery as possible. . . . Can we hesitate? COME North! . . . Troubles will ensue with white unions and householders, but remember that the chief source of these troubles is rooted in the South; 1 million Southerners live in the North. . . . This is a danger, but we have learned how to meet it by un-wavering self-defense and by the ballot.30

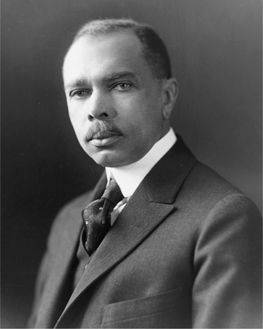

Fig. 5.2. W. E. B. Du Bois at work, early in the 1900s. (Atlanta University, 1909.)

The Crisis is only one source of the sentiment of the times. Some things surely escaped Du Bois’s attention but fueled the self-defense assessments of the people who witnessed them. These incidents elicited a range of reactions and critiques that expand our understanding of the black tradition of arms.

One reaction to racist terrorism was to move away from areas of risk. In Kentucky, for example, documented movements show that lynch violence pushed many rural blacks toward the protection of burgeoning black communities in Louisville and Lexington. Capitalizing on this trend, some rural towns installed neatly painted signs warning, “Niggers don’t be here when the sun goes down.” A sign with that warning stood in Corbin, Kentucky, until the 1960s.31

While flight was one reaction to the threat of violence and racism, another was to take up arms, pray for the best, and know that someday a fight might come. The precise calculations, the guns acquired, and the way they were kept or carried, cannot be fully retrieved. Still, there is abundant evidence of Negroes with guns fighting back against Judge Lynch and lesser threats.

Some of this evidence raises worries about accuracy that afflicts oral histories. The account by former slave Richard Miller is one of these. But it is independently useful for what he presumes people would credit about the black culture of arms. Miller proudly recounted to an interviewer the heroics of George Bland, a former slave living in Danville, Kentucky. Some offense led to the lynching of Bland’s wife by Klansmen, who forced him to watch. Bland asked the terrorists if he could retrieve a blanket to wrap her body. Then, according to Miller, Bland walked into his cabin, “got his Winchester rifle, shot and killed 14 of the Kluxers.”32

Researchers worry that the tale seems too fantastic to credit, especially the killing of fourteen Klansmen. This is a fair skepticism. On the other hand, the feat was certainly within the capabilities of available technology. Fourteen Klan casualties comports with the capacity of the Winchester Henry rifle, an early test of which records fifteen shots fired in roughly ten seconds.

The era of lynching and nightriders is filled with gruesome tales of hapless victims, running, hiding, and cowering under waves of violence. But there are also plenty of verifiable episodes that track Richard Miller’s tale of George Bland. Sometimes, as in the case of George Dinning, these self-defense efforts were even deemed legitimate by the ruling bureaucracy. George Dinning was born a slave, was illiterate, and had at least twelve children. But he also was industrious and frugal. He worked and saved to buy a small farm, and by 1897 he had added more acreage and built up a heard of livestock.

Some of his white neighbors were irritated by Dinning’s growing prosperity. In the winter of the new year, twenty-five of them marched to his homestead and demanded that Dinning leave the county within ten days. Their pretext was that Dinning was a thief of chickens and hogs. Dinning protested that he had sponsors, white men of status who would vouch for his honesty. This was taken as impudence that led to harsher words and then shots fired at a backpedaling Dinning. Bullets riddled his house. Dinning was hit twice.

But Dinning was not helpless. He had guns and knew how to use them. Bleeding from his wounds, Dinning scrambled to his rifle and opened fire, hitting and killing one man. With one of their company wounded, the mob scattered off. Expecting them to regroup and return, Dinning fled his home and turned himself in to authorities at the county seat. Learning that Dinning was in custody, the mob went back to his farm, drove off his wife and children, ransacked his house, and then burned it to the ground.

Dinning was tried for murder after two changes of venue and the deployment of state troopers to avert a rumored lynching. On the testimony of the mobbers, Dinning was found guilty of manslaughter by a white jury and sentenced to seven years of hard labor.

It was some flicker of progress that Dinning’s story did not end here. Black support for Dinning was overwhelming. Black churches and political clubs bombarded the governor with letters urging him to pardon Dinning. Governor William Bradley, a rare surviving southern Republican, reviewed the trial transcript and published his findings: Twenty-five armed men had attacked George Dinning as he was working peacefully on his own property. They had fired first. Bradley concluded that Dinning, “in protecting himself . . . did no more than any other man would or should have done under the same circumstance and instead of being forced to wear convict’s garb he’s entitled not only to acquittal but to the admiration of every citizen who loves good government and desires the perpetration of free institutions.”

Upon release, Dinning was under no illusion that the Republican governor reflected the sentiments of the broader community. His Kentucky homestead destroyed, Dinning moved his family west to Indiana. Once settled, he hired a lawyer to bring a civil suit in federal court against his attackers. He won a $50,000 verdict against six of them, including a lien on the estate of the mobber he killed.33

George Dinning’s luck, perseverance, and the measure of justice he scratched from the legal system are remarkable. On the other hand, Dinning’s basic fighting instinct, his resolve to arm himself, and his willingness to use his gun in righteous self-defense are far from unique.

Moving into the new century under the shadow of lynch law, Negroes were wary of the sounds and signs of mob violence. The signals were glaring in 1902, when a black man named Charles Gaskins sat in jail, awaiting trial for the murder of a Flemingsburg, Kentucky, police officer. On a raw winter evening, roughly sixty white men rushed the jail and attempted to batter down the cell door with a sledgehammer.

They were quickly distracted from their quarry by shotgun blasts from across the street. Local papers reported, “this had the effect of scattering the mob which left as quickly as it came.” The gunfire was rumored to have come from a clutch of black men who were loosely related to the prisoner. But no one was ever definitively named as the savior of Charles Gaskins. And the assumption that Gaskins would eventually be executed anyway turns out to be wrong. He is not in the generally reliable records of executed criminals.34

While the armed defenders of Charles Gaskins remain unknown, the case of Jacob McDowell confirms the intuition that relatives of lynch targets would be among the first wave of resistance to mobbers. Jacob McDowell was a “hard-working colored man of mature years” who eked out a living within the boundaries of the opportunities allowed to blacks in western Kentucky in 1908.

We know of him because of a conflict that started over a black girl. McDowell confronted Smith Childress, a deputy marshal, objecting to Childress’s relationship with the girl. It is unclear exactly what they said, but the tone was surely hostile. On one account, after McDowell had his say and started to walk away, Childress took a shot at him. McDowell fled into one of the stores on Main Street with Childress in pursuit. They scuffled, and McDowell ended up shooting Childress with his own gun. With Childress lying wounded, McDowell ran to the jailhouse to explain what happened. Familiar with the local history of mob violence, the police judge removed McDowell to the next county, where he could be better protected.

Kentucky officials were not the only ones wary of the mob. McDowell’s son, Harve, had seen this scenario unfold before and was skeptical about how much risk jailers would take to protect his father. So he gathered eleven trusted men to help stand guard. They were on foot, traveling toward town, when angry men on horseback approached from behind. Accounts differ about what happened next. Whites said that Harve had hidden on the side of the road with a plan to ambush them. Harve McDowell and his cohorts said they moved off the road to hide so that the whites would pass without confrontation.35

According to McDowell, the shooting started as his group was climbing over a fence into the cover of an adjoining field. One of the black men got snagged on the fence and his gun went off, shooting McDowell in the leg. This revealed their position and drew fire from the whites. McDowell and some of his men fired back. Others ran away.

When the smoke cleared, one white man was dead and another one seriously wounded. Both of these men, it turns out, were simply traveling through the area and had come along for the adventure of seeing a lynching. The aftermath was familiar. For the next two days, a mob roamed the countryside, threatening and interrogating Negroes until they learned the identities of the men who had gathered to protect Jacob McDowell.

Meanwhile, Jacob McDowell was returned back to the venue of his original confrontation with Smith Childress. It was a curious decision, because the danger that caused authorities to move him the first place seemed clearer than ever. This was confirmed when a group of masked gunmen entered the jail, dragged Jacob McDowell to the outskirts of town, and riddled his body with gunfire. In a subsequent assessment of the McDowell lynching, a pamphleteer claimed that Smith Childress, the deputy marshal who fired the first shot in the saga, actually led the lynch mob. The suspicion was that Childress feared that a trial of Jacob McDowell would publicize his tryst with a black girl.36

The McDowell case confirms that state agents were sometimes complicit in mob violence. But as we saw in the case of George Dinning, state agents were not always villains. This was decidedly the case in Stanford, Kentucky, where a white jailer acted boldly against type.

The conflict started when an argument between two black boys and three white farmers left a white man down from gunfire, and the two young Negroes behind bars. Word of the shooting, the arrest, and the impending mob traveled quickly. Within hours, armed Negroes from Macksville, a neighboring all-black settlement, arrived in Stanford to guard the jail. They planned for gunplay in dim light by wearing white ribbons on their left sleeves to avoid casualties from friendly fire.

Unlike Charles Gaskins’s unknown defenders who fired from the shadows, the Macksville men stayed boldly in the open, building a bonfire in the street behind the courthouse and shooting out at bumps in the night. The effect of this show of force on the white jailer was remarkable. He took uniquely aggressive action, placing his son in the cell with the black prisoners and handing guns to all three of them. This was enough to dissuade the mob.

It is unclear whether Negroes who ran to defend their neighbors in this fashion were calculating the odds of success in any serious way. The Macksville defenders could not have known that a show of force would diffuse the mob without a fight. Neither could the defenders of Dollar Bill Smith, in Wiggins, Mississippi, have predicted trading five hundred shots with a looming mob. Smith was a known “bad nigger,” at least according to the mobbers. So they were inflamed by the idea that local Negroes would stand up to save him from the noose. With blacks massed in the Negro section, the mob rolled in to teach them a lesson. The Negroes gave as good as they got. There were multiple casualties on both sides, but evidently no one died.37

Of course, there is plenty of evidence from the early twentieth century that armed self-defense could end badly for Negroes. Witness the episode in Sunflower County, Mississippi, home to infamous segregationist Senator James O. Eastland. The senator’s uncle James owned a 2,300-acre plantation near Doddsville. In the winter of 1904, he rode to the cabin of one of his sharecroppers, Luther Holbert. He aimed to mediate a conflict between Holbert and one of Eastland’s favored workers. The trouble stemmed from a love triangle involving Holbert’s woman. Eastland was armed with a revolver. Holbert had a gun in his cabin.

We don’t know the words they exchanged, but it is clear that Holbert shot James Eastland, who died on the cabin floor, with two shots fired from his revolver. A posse combed the countryside for Holbert, and in the process killed two Negroes who ran at the sight of furious, armed men on horseback. Holbert was tracked down and lynched, along with his woman, who fled with him.38

The progression of gunplay surrounding Charles Gaskins, Jacob McDowell, Dollar Bill Smith, and Luther Holbert leaves us wondering what sorts of calculations people who witnessed these events made about the risks of owning, carrying, or using guns. Did news of the bloodless Negro triumph in defense of Charles Gaskins embolden Negroes and prompt folk to acquire guns? What about the lynching of Luther Holbert? Did it convince Negroes that armed self-defense was just folly? Or did that also counsel keeping and carrying firearms?

Answers are suggested in the tilt of local lore surrounding the 1901 “Balltown Riot” in Washington Parish, Louisiana. The violence sparked on rumors that blacks were stockpiling weapons in preparation for an attack on local whites. Whether this was a real fear or just an excuse is unknown. But we know for sure that a white mob surrounded and then shot into a black church whose members were at the root of the rumors. The Negroes were prepared for conflict. They returned fire, killing three white attackers. Fifteen blacks died.

The Balltown Riot is ostensibly a story of black defeat, perhaps confirming for modern skeptics the folly of armed self-defense. But the fifteen-to-three body count is the “white” record of the violence. Among the local black folk, the accounting was different. Years later, those who lived through it said that the body count was closer to even, but that white officials had doctored the story. As the details grew into legend, witnesses recounted that three white casualties was a vast undercount. One man, recalled proudly how “old man Creole [himself] killed about six.”39

This sort of account demonstrates a kind of tribal pride that appears frequently in stories of armed self-defense against terrorists. As we will see in the next chapter, America’s preeminent black historian, John Hope Franklin, offers a similar critique of the 1921 race riot in Tulsa, Oklahoma. These kinds of assessments suggest the cast of the black tradition of arms. Armed self-defense was often embraced as a matter practical philosophy, undiminished by utilitarian balancing.

There were many incidents where black defenders, armed with the guns of poor folk, were outclassed by better technology. Economics was one driver of these results. But we already saw under the Black Codes, and will see again in the Jim Crow era, how gun laws administered by an overtly hostile state also impaired Negro self-defense. A lynch episode from 1916 demonstrates a small scale, ad hoc version of this.

The first lesson is in the lynching itself. The location was Paducah, Kentucky, where, in 1892, armed Negroes fought off a lynch mob and earned the praise of Ida B. Wells. Perhaps it was memory or legend of that fight that moved Luther Durrett to a desperate act in aid of his cousin Brack Henley.40

Henley was arrested on the charge of assaulting a white farm girl. A mob stormed the jail and dragged him to the victim’s house, where she nodded that yes, he was the one. As they were about to yank Henley up by the neck, Luther Durrett stormed from the brush, waving a pistol and threatening to fire into the crowd. He was vastly outnumbered, quickly overpowered, and strung up on a limb next to his cousin.

The lynchings of Henley and Durrett left blacks seething and fueled white rumors that they were planning a retaliatory attack. Those rumors seemed confirmed when scores of Negroes attempted to buy guns from local hardware stores. They were thwarted by Paducah police, who ordered local merchants not sell guns to blacks.41 At least fifty Negroes were turned away on these orders.

This ad hoc gun prohibition and the fact that black rage here never resulted in gunfire allows several speculations. One is that blacks were unable to get guns, and that diffused what might have become a swirling cycle of violence. But that assumes that blacks were not already widely armed. And given the other signals of black gun ownership, that would be surprising. The alternate speculation is that the lynch violence in Paducah spurred unfilled black demand for additional firearms consistent with the modern “fear and loathing” hypothesis, which says that incidents of violence spur acquisition of firearms for self-protection.42

It turns out in any case that the community was not entirely pacifist in its response to the Henley and Durrett lynchings. One of the lynch instigators, George Ross, fled Paducah after multiple threats to his life. The anger of the community seeped out again against a white police officer who was beaten after responding roughly to complaints about a loud Halloween celebration.43

While hostile state actors loom large in the lynch era, that story is complicated by men like Augustus E. Willson, Republican governor of Kentucky, who administered the state in the early twentieth century. Elected in 1907, Willson was, for the time, remarkably aggressive in his criticisms of lynch law and his willingness to combat midnight terrorists. His reaction to the mob murder of David Walker and his family in Hickman, Kentucky, matches our modern outrage.

The Walkers were attacked because they were “uppity” Negroes who did not know their place. One account described David Walker as a “surly Negro” who had cursed a white woman in some commercial transaction and threatened a white man who came to her defense. Later, masked by darkness, midnight terrorists rode to Walker’s cabin, crept in close, and yelled for Walker to come out. When Walker refused, they doused the structure with kerosene and set it afire. With his house in flames, Walker fired on the mob and then wilted under a barrage of return fire. His wife ran from the house with a baby in her arms. She and the child were shot down. Three of Walker’s other children tried to flee but were also killed. Walker’s oldest son refused to leave the burning structure or perhaps was already dead by gunshot.

Governor Willson’s response distills the scene. “If two or three men had gone to this poor man’s cabin and murdered his family, the crime would’ve shocked humanity with its revelation of incredible weakness, brutality and dastardly cowardice. That a larger number—some fifty men—joined in such a crime, multiplies its cowardliness and wickedness fiftyfold, and makes every member of the band guilty of murder in the first-degree.”44 Willson rejected the argument that nightriders were just good people frustrated by black criminality, and he castigated public officials who countenanced terrorism on that excuse. The epidemic of lynchings in Kentucky, he said, was “the logical [result] of the toleration of nightrider crimes in the state.”

Willson’s policy response to terrorist violence had wide appeal among blacks and fits comfortably within the black tradition of arms. In addition to offering a $500 reward for the arrest and conviction of anyone complicit in lynch violence, Willson urged Negroes to defend themselves and promised to pardon anyone who shot a nightrider in self-defense. In a speech to the American Bar Association, Willson declared that “every man who is a member of a lawless band that goes with the double cowardice of those who enter upon lawlessness with the protection of the night and of overwhelming numbers against one poor and helpless man . . . takes his life in his hands and if the victim in despair kills him, no one has any right to complain.”

The Kentucky Courier-Journal subsequently reported various accounts of nightriders killed by blacks in Birmingham, Golden Pond, and other western Kentucky towns. A judge in Lyon County wrote to Willson that many blacks eventually were driven from the area, but not without taking their share in blood and flesh. “I have learned that a man in this county saw the gang on its march to Birmingham counted them, saw them as they returned . . . and one man was lying on his horse, head hanging to one side feet on the other, another was held in the saddle by a man riding behind . . . four others are visited by a doctor from Kuttawa. . . . There were three secret burials [of nightriders] in this County and one in Marshall.”

Willson sent troops to western Kentucky and kept them there for more than a year. He used state funds to provide guns and ammunition to people who were under threat of attack. His pressure on local leaders led to the arrest and trial of several lynch-mob instigators. Finally, though, Willson confronted the boundaries of his power. He could press for arrests and trials, but he could not convict terrorists and murderers. Ultimately, all of the men arrested under pressure from Willson were acquitted by juries of their peers.

The Walker lynchings that so animated Governor Willson demonstrate the uncertain curve of armed self-defense, its potential for making things worse, and the difficulty of making sound after-the-fact-judgments about it. Some reports say that the mob descended on David Walker intending just to horsewhip him. But “when he fired into their midst he so aroused their indignation that their thirst for blood was not sated until the last member of the Walker family had been shot.”45

So did Walker’s gun just make things worse? Was he a fool who provoked the deaths of his entire family when he could have avoided it all by taking a whipping? Or was Walker a hero who deserves admiration for his defiant last stand? And is there some inherent value to desperate but failed defiance? Or is it better to surrender and live another day under the yoke? One would pay to hear David Walker’s answers to these questions.

The black tradition of arms grew out of countless decisions by men like David Walker to own and carry guns. These decisions were necessarily calculated. Acquiring guns required balancing of scarce resources. Carrying guns from one situation to the next demanded estimates of oscillating risks and rewards. On the other hand, the decision to actually use the gun in self-defense often seems like just a spontaneous reflex. That probably explains the episode in 1908, in Logan County, Kentucky, where Rufus Browder, a black sharecropper, fought with and ultimately killed his landlord.

They argued over some trifle. Then Browder turned his back to James Cunningham and walked away. This affront, a clear violation of racial etiquette, provoked Cunningham to violence. Cunningham cursed Browder for his insolence and slashed him with a whip.

Browder’s immediate response is unrecorded. But he probably struck back, because Cunningham went from the whip to a pistol and shot Browder in the chest. Wounded, but ambulatory, Browder pulled his own pistol and killed Cunningham. Browder was arrested for murder and moved to a jail in Louisville, Kentucky.

Browder escaped lynching, but four of his lodge brothers did not. Browder was a member of one of the many fraternal organizations that blacks developed as surrogates for absent social-services networks. These groups administered burial funds, pooled emergency assets, and were sometimes the organizational base for vigilance and self-defense groups. Rumor spread among whites that Rufus Browder’s lodge brothers were plotting a preemptive attack on whites who had threatened to mob Browder.

Four lodge brothers were meeting in a private home when police entered and arrested them for disturbing the peace. While they were sitting in the jail in Russellville, Kentucky, a mob of nearly one hundred men descended and demanded that the jailer give them up. He handed over the keys, and the four men were summarily hanged. The mob pinned the message on one of the corpses, “Let this be a warning to you niggers to let white people alone or you will go the same way.”46

Negro men were the primary victims of lynch law. But black women were also targets of mobs and sometimes beneficiaries of the armed community. Marie Thompson was both. Around 1904, in Lebanon Junction, Kentucky, Marie Thompson was arrested for murder of a white farmer. The humanized picture of Marie is lost. White press reports caricature her as a “Negro Amazon,” an evident attempt to explain how she had managed to kill a stout white farmer who chastised her son over some missing tools. Thompson claimed that she had acted in self-defense.

Anticipating the mob, black men from the community assembled with guns to guard the jail. They repulsed a late-evening attack, and apparently concluded that the danger had abated. But deep into the night, Marie Thompson was snatched from her cell by men who seem to have gotten access without resistance from the jailer.

Bolstering the Amazon legend, Thompson was dangling from a rope, seemingly dead, when one of the mob ventured too close. Thompson sprang to life, grabbed the man by his shirt, snatched a knife from his hand and cut herself free. Now wielding the blade, she waded into the mob. Unwilling to engage her hand-to-hand, the mobbers killed Marie Thompson with a volley of gunshots.47

The self-defense impulse played out badly for Marie Thompson. It is hard to avoid the conclusion that everyone would have been better off if she had just stayed out of the conflict between the white man and her son, which might have ended with just harsh words and her boy submitting to a light beating. But the difficulty of translating that insight into general policy is illustrated by the murder of Kentucky farmer Jim Hill.

Jim Hill got into a scrape with a white man named L. J. Swift that left Hill missing three front teeth. Hill sought redress through the legal system, asking the county prosecutor to issue a warrant for Swift. County bureaucrats went through the motions. But Hill’s complaint ultimately was dismissed on Swift’s testimony that Hill had talked back and made threats.

Unsatisfied with the victory in court, Swift lead a group of men to Hill’s farm about a week later. With guns drawn, they forced a sack over Hill’s head and dragged him from his home. They did not announce their intentions. Perhaps they planned a beating, perhaps a whipping. Perhaps they only intended to frighten Jim Hill enough that he would never again invoke the law against a white man.

Jim Hill’s wife had only seconds to make a decision. And if she had drawn a lesson from Marie Thompson, she might have decided just to let them drag her husband off into the night. She hesitated, and then, fighting off a kind of fear that is difficult for us to imagine today, she pursued the mob with a rifle in one hand and a lantern in the other. She was willing, but the results leave one wishing she had been more effective. The lantern turned out to be a tactical mistake that made her a target. Ducking under gunfire, she lost her lantern and her gun. With Jim Hill’s only defender subdued, the mob dragged him into a field and beat him to a gel.48

Individual calculations about the wisdom of owning or carrying guns surely varied. Even today gun ownership rates and the data about how many people carry concealed firearms are only estimates from surrogate information. The early twentieth century offers its own sinister surrogate for estimating the frequency with which Negroes carried guns. A study of the southern convict labor system shows that it was quite common for black men of the era to travel armed. It is contestable whether the convict labor system was more about crime control or more about dragooning cheap labor. There is a strong argument for the latter, given the frequency with which black men were roped into the system on charges like “idleness,” “using obscene language,” “selling cotton after dark,” and “violating contract” with white employers in places where true crime was almost trivial.

Men arrested on these specious charges were jailed and fined. If they could not pay, and many couldn’t, their term was extended and their fines and fees compounded. Now even further in debt, they were essentially sold to anyone who paid their fines and were required to work off the debt. The case of Green Cottenham is emblematic. He was arrested for vagrancy in March 1908, spent three days in jail awaiting trial, then was found guilty and sentenced to a fine or thirty days hard labor. Green Cottenham had no money, so he did the thirty days. But this meant he racked up an array of fees for his keep. Soon his debt equaled one year of hard labor, and the obligation was purchased by a railroad subsidiary of the northern industrial giant US Steel.

Perhaps as many as two hundred thousand black men were snared into the convict labor system on a variety of pretexts. One of the most common charges was carrying a concealed firearm. This was era when many southern men carried side arms. But the crime of carrying a concealed weapon was enforced mainly against Negroes. By the turn of the century it had become one of the most consistent instruments of black incarceration. The indications that arrests for carrying a concealed gun were more frequent than arrests for things like idleness and using obscene language suggests a robust culture of keeping and bearing firearms that thrived despite the risk that it was a pathway into the convict labor system.49

Labor supply was the seed of racial violence in East St. Louis, Illinois. And the aftermath brings another appearance from the storied advocate of the Winchester rifle, Ida B. Wells, now married to Chicago striver Ferdinand Barnett. Negroes had been migrating to East St. Louis for at least a decade. This rising population was either a threat or an opportunity, depending on whom you asked. Democrats saw the influx of likely Republican voters as a threat. Woodrow Wilson worried aloud that the rising black population of East St. Louis was a Republican plot.50

On the other hand, Negro labor was an important strategic asset for industrialists in contests with the bourgeoning local labor movement. The country had just entered World War I when white unionists struck local meatpacking and metal-refining companies. Management responded by hiring black replacements who crossed picket lines.

In the spring of 1917, more than three thousand union men marched to City Hall to protest the unfair labor competition. Riled by angry speeches and fearing permanent displacement by cut-rate black labor, the crowd raged through the streets, destroying property and assaulting any Negroes they could lay their hands on. The governor sent troops to quell the rioting, at least for the moment.

But the underlying source of the conflict, Negroes who would work cheaper than whites, remained. And the black folk of East St. Louis knew to prepare for more violence. Black defense preparations also raised the perennial dilemma about whether arming in anticipation of conflict actually elevates the risk. Is it better to avoid such preparations on the worry that they escalate the risk and spur cycle of violence? Or do violent aggressors prey on weakness?

The rioting in East St. Louis ultimately prompted a congressional investigation. The conclusions were contested, but the formal findings laid much of the blame on black defense preparations. The precise focus was community leader Leroy Bundy, a relatively affluent black dentist. After the initial attacks in May, Bundy urged Negroes to keep their guns in good order and to acquire more where they could. According to the congressional report, this set East St. Louis on edge and sparked the conflagration.51

Fig. 5.3. Reporting on the East St. Louis riot. (Springfield Republican, Springfield, Massachusetts, July 3, 1917.)

The community was armed and primed for conflict when a car full of men drove through, shooting at shop windows and bystanders. When the car returned a short time later, Negroes with guns were prepared and fired preemptively, killing two men inside. But there was a mistake. This was not the same car. This was a car full of plainclothes policemen. And now Negroes had shot and killed two of them.52

Whites responded in a rampage that killed at least forty Negroes and destroyed multiple blocks of East St. Louis’s black enclave. The NAACP pleaded with President Wilson to condemn the mobbing. Wilson said nothing. Investigators called the black defense preparations a conspiracy to riot instigated by Leroy Bundy. Bundy was charged with the murder of the two slain officers.53

Through the intervention of Ida B. Wells and her husband, Ferdinand Barnett, Leroy Bundy ultimately was cleared of the murder charges. In the aftermath, Ferdinand Barnett’s advice reflected a common assessment of whether preparing for armed self-defense was a worse option than disarming and hoping for protection from the government. At a mass meeting of Negroes following the riot, Ferdinand Barnett advised his roaringly sympathetic audience, “Get guns and put them in your homes. Protect yourselves. Let no black man permit a policeman to come in and get those guns.” Perfectly in sync with her husband’s advice, Ida Wells urged that “Negroes everywhere stand their ground and sell their lives as dearly as possible when attacked.”54

Fig. 5.4. A family portrait of Ferdinand Barnett and Ida B. Wells Barnett. (Photograph from 1917.)

Looking back, we know that things would improve for blacks over the twentieth century. But one wonders how W. E. B. Du Bois thought about the prospects for American Negroes in private moments of candor. Did he question the wisdom of staking his future here? Unlike many black folk, he had options and made a conscious bet on the United States of America.

Du Bois had lived and studied abroad. He had fallen for a German girl, or at least she had fallen for him. He could have stayed in Europe. But he returned, resolved to fight both politically and, if we credit his rhetoric, physically. His writing in the Crisis demonstrates that resolve.

But Du Bois was no isolated, intellectual radical. While he extolled self-defense rhetorically in the Crisis, the NAACP as an organization expended time, talent, and treasure to uphold the principle on behalf of black folk who defended themselves with guns. That fight consumed much of the young organization’s resources.

From our vantage point today, the NAACP’s work in support of armed self-defense seems remarkable. What, indeed, to make of the fact that armed self-defense was at the core of the first major case the organization supported? The year was 1910, and Pink Franklin, a South Carolina sharecropper, was accused of murder.

Considering the times, it was fortunate that Pink Franklin was not summarily lynched. His initial offense, the “crime” that started it all, was a basic breach of contract. Today this sends people to court in civil actions, seeking a stingy measure of damages to compensate for their disappointed expectations. Even in 1910, for white folk complaining about breach of contract, that was the remedy. But for a black sharecropper, the stakes were far higher.

Pink Franklin violated a special category of agricultural contract that was regulated under the South Carolina Criminal Code. It was a species of the peonage contracts that defeated Confederates attempted to enforce immediately after the Civil War under the Black Codes. The law said that sharecroppers who breached these agreements with planters could be punished by fines and imprisonment. The injured planter could secure his remedy through an arrest warrant enforced by the local magistrate. Negro contract breakers who could not pay their fines and mounting fees from incarceration might then be sold off under the convict labor system into a life that was just a step away from slavery.

Pink Franklin had indeed breached his contract. He signed on as a tenant farmer with one planter and then left for a better deal at another farm. The first planter claimed that Franklin still owed him money. That was enough to secure a warrant for Franklin’s arrest. Lawyers would quibble later over whether the law authorizing the warrant was unconstitutional. But that grand illegal question would not be settled in time to shield Pink Franklin from the wrath and caprice of a jilted employer and a malevolent government agent.

In the dark of the early morning, around 3:00 a.m., armed men descended on Franklin’s shanty, dubious warrant in hand. Stories conflict about the details. Franklin said that he was surprised in the middle of the night by strange men in his bedroom. When one of them shot him in the shoulder, Franklin dived to the floor, rolled to the gun he kept in the corner, and came up shooting.55

A surviving constable claimed that both the front door to Franklin’s home and Franklin’s bedroom door were ajar; that they knocked, entered, and then were surprised by gunfire from Franklin, an ax attack by Franklin’s woman, and a flying tackle by Franklin’s young son. There is no record of exactly what type of gun Franklin used. But it certainly was something more advanced than the single-shot technology often employed by poor folk, because two constables fell to Franklin’s gunfire. One of them, Henry Valentine, eventually died from his wounds.

Franklin was convicted of murder and sentenced to death. The NAACP supported the case through an appeal to the United States Supreme Court and then, with the aid of Booker T. Washington, lobbied the governor of South Carolina to commute Franklin’s death sentence to life imprisonment. In 1915, Franklin’s case was reopened, and he was paroled in 1919.56

Shortly after taking on the Pink Franklin case, the NAACP assisted another tenant farmer charged with murder under similar circumstances. Steve Green of Arkansas walked off from his peonage contract after his landlord doubled his rent. On no legitimate authority, the planter forbade Green from ever working in the county again. It was the kind of arrogant demand that only makes sense in that time and place.

Bristling with racial entitlement, Green’s jilted landlord came gunning for him after learning that Green was working for a neighbor. He did not come to negotiate. He just rode over to Green’s new job and opened fire. The attack left Green bleeding but alive. Green retreated home, briefly tended his wounds, then grabbed his Winchester and went after his attacker.

Green turned out to be a better shot than his former boss, killing him efficiently and then fleeing. With the aid of friends and neighbors who hid him and then pooled money for a train ticket, Green made it to Chicago. Fresh in the big city, he managed to get arrested on a specious charge of petty larceny. From there, police connected him to the incident in Arkansas. Through the NAACP and with the assistance of Ida B. Wells, Green contested extradition to Arkansas. With extradition proceedings pending, Green fled to Canada.57

In 1919, a cash-strapped NAACP took on another armed self-defense case, coming to the aid of Sergeant Edgar Caldwell, an active-duty soldier stationed at Fort McClellan, Alabama. In December 1918, Caldwell was traveling into Anniston by streetcar when he provoked the wrath of a white conductor, Cecil Linton. Caldwell had dared to sit in the white section of the car. Linton figured to drag Caldwell from the forbidden zone. But Caldwell had a different idea. With the advantage of either strength or technique, Caldwell launched Linton through a glass divider between the cars. Linton called for help to the motorman, Kelsie Morrison, and they managed to throw Caldwell off the car. As Caldwell lay in the street, the two trolley-men advanced to give him a beating for good measure. Morrison, in his motorman’s boots, stomped Caldwell, landing solid blows to the ribs.

Criminologists tracking mid-twentieth-century homicides would document that beating equaled and sometimes surpassed shooting and stabbing as a mode of criminal homicide.58 Edgar Caldwell had no PhD in criminology, but he was a decorated veteran of World War I. He understood that death could come from hands and feet as well as knives and guns. Trapped on his back, writhing under the boot heels of Linton and Morrison, Caldwell drew his service revolver and shot twice, killing Linton and wounding Morrison.59 It is encouraging that Caldwell was not immediately lynched. But that is offset by the fact that, during the same period, the NAACP protested a spate of mob killings of returning black veterans who were hanged or burned while still wearing their uniforms.60

Due largely to the legal assistance and political maneuvering of the local and national NAACP, including a failed appeal to the United States Supreme Court, Sergeant Caldwell survived for almost two years on death row before being executed. Over this period, Caldwell became a household name among Negroes. Writing in the Crisis, W. E. B. Du Bois detailed the efforts to save Caldwell and framed the issue as whether blacks would be afforded the basic prerogatives of manhood. The legendary NAACP Legal Defense Fund had yet to be formed, so the cash-strapped organization made direct appeals in the Crisis for donations to fund Caldwell’s defense.

In the March 1920 edition, the Crisis published a full-length photograph of Caldwell with the appeal, “We want 500 Negroes who believe in Negro manhood to send immediately one dollar . . . for Caldwell’s defense.” The plea resonated with donors who responded not only with dollar bills mailed to NAACP headquarters in New York, but also notes and cards supporting the ideal of “Negro Manhood” exemplified by Caldwell’s armed stand.61

After Caldwell’s execution, Du Bois eulogized him as a martyr for black manhood and described the execution as, “one more addition to the long list of crimes which have been done in the manner of color prejudice.” Du Bois’s reaction was actually quite reserved by comparison to at least one other black intellectual of the day.62

Commenting on the class of hazards that snared Edgar Caldwell, Hubert H. Harrison wrote in 1921, “I advise you to be ready to defend yourselves. I notice that the State Government has removed some of its restrictions upon owning firearms, and one form of live [sic] insurance for wives and children might be the possession of some of these handy implements.” Harrison, described by A. Philip Randolph as “the father of Harlem radicalism,” was at the time, more militant than Du Bois. Although he is largely unknown today, one source calls Harrison “the foremost Afro-American intellect of his time” and “one of America’s greatest minds.”63

In 1923, the NAACP took another armed self-defense case to the Supreme Court. In Moore v. Dempsey, the association came to the aid of a group of black World War I veterans who returned to Elaine, Arkansas, intent on building something better than what they left. Many of the men returned to sharecropping but now demanded fair treatment, fair wages, and accurate accounting.64

Organized under the banner of the Progressive Farmers and Householders Union, they had hired lawyers and were gathered outside the town of Elaine to plot strategy. The union threatened many entrenched interests. So it was no surprise when a Phillips County deputy sheriff and agents of the Missouri Pacific Railroad arrived to break up the meeting and discourage any more of them, with a little rough treatment.

Standing on the privilege of race and office, the head lawman fired preemptively on the Negroes. Perhaps he worried that he would kill or injure someone, perhaps not. Maybe he was surprised when the simple black farmers, now steeled by combat, fired back. Whether surprise or anger, it would be the deputy’s last emotion before he fell dead from Negro gunfire.

The white response was immediate and overwhelming. The sheriff deputized several hundred men and the governor mobilized troops. This force scoured the countryside ostensibly to find the shooters but ultimately in a campaign of retribution. But the going was harder than they expected, with black resistance yielding five more white casualties. The black casualty count, on the other hand, was at least twenty-five.65

Scores of Negroes were indicted for murder by an all-white grand jury. A few perfunctory trials produced verdicts of first-degree murder, which carried the death penalty. After that, most of the defendants pleaded guilty to second-degree murder, with its lesser penalty of life in prison. One of these sham trials lasted less than an hour, with the defendant first meeting his lawyer in the courtroom.

The NAACP pursued the cases to the Supreme Court, buoyed by tens of thousands of dollars of donations from around the country. Writing for a divided court, Oliver Wendell Holmes reasoned that the convictions must be reversed because the so-called trials were essentially an extension of the mob, and a sentence of death or imprisonment driven by mob passions was a violation of due process. The case was a grand victory for the NAACP. The optimistic observer might have taken it as affirmation that at the rudiments of a fair trial would extend even to Negroes who took up guns against capricious state authorities.66

In the very early stages of NAACP activism, substantial work occurred in the branches. The Detroit branch was particularly active and pressed several pieces of litigation challenging discriminatory commercial practices. Most of those efforts focused on local problems. But in one case the Detroit branch stretched its reach and captured national attention. Like important cases that followed, it was rooted in an act of armed self-defense.

The violence started in Georgia, where tenant farmer Thomas Ray repelled the threats and assault by his landlord with deadly gunfire. It was 1920, and Ray had a sufficient sense of southern justice to know that he should flee. He almost made it into Canada when he was apprehended by Detroit police.

As word of Ray’s plight spread, the Detroit branch flew into action. The branch funded lawyers who blocked Ray’s extradition, arguing that he would be lynched if returned to Georgia. And although NAACP branches were often the bastions of the Talented Tenth, the Ray case captured the passions of the entire community.

When rumors spread that whites had threatened to seize Ray from the jail, working-class men from the Negro enclave of “Black Bottom” ran to stand guard around the courthouse. The combination of formal legal proceedings and the community’s resolve to protect Ray from the mob ultimately succeeded. In June 1921, more than a year after Thomas Ray had fled Georgia, the governor of Michigan freed him on the determination that he had shot in self-defense.67

At the close of World War I, W. E. B. Du Bois proclaimed in the Crisis that “we are cowards and jackasses if now that the war is over, we do not marshal every ounce of our brain and brawn to fight a sterner, longer, more unbending battle against the forces of hell in our own land.” This militant call was not shared by everyone at the NAACP. And it certainly did not reflect the views of John Shillady, the organization’s white executive secretary, a pacifist who abjured violence even at a personal level. After a mob attacked Negroes in Longview, Texas, in 1919, Shillady traveled to investigate. He was there only two days before he was assaulted by a white gang. He applied pacifist tactics and curled up into a little ball while they beat him senseless. Within a year, he had resigned from the NAACP.68

Shillady’s replacement, James Weldon Johnson, the association’s first black executive secretary, took a different stance. Following the July 1919 race riot in Washington, DC, Johnson investigated and offered this assessment of how and why peace was restored. “The Negroes saved themselves and saved Washington by their determination not to run but to fight, fight in the defense of their lives and their homes. If the white mob had gone unchecked—and it was only the determined effort of black men that checked it—Washington would have been another and worse East St. Louis.”

The violence in DC was sparked by a rumor that a white soldier’s wife had been raped by a Negro. The city was filled with military men back from World War I. It also had been filling for some time with blacks migrating out of the South in search of something better. On a hot Saturday in mid-July, hundreds of white veterans rampaged through DC’s black neighborhoods. The violence continued two more days, peaking on Monday after an editorial from the Washington Post urged “every available serviceman to gather at Pennsylvania and Seventh Avenue at 9:00 p.m. for a cleanup that will cause the events of the last two evenings to pale into insignificance.”

White servicemen answered the call and stormed through black neighborhoods in the southwest and Foggy Bottom. But the going was tougher in northwest Washington, DC, where the forewarned community was barricaded in and well-armed. As the mob approached, Negroes answered with a barrage of gunfire. The mob scattered. In the aftermath, cars were found riddled with bullet holes. Dozens of people were seriously wounded and one black man died by gunshot.

Black gunfire certainly helped staunch the mob. But it also helped that Washington was drenched by torrential rains and that President Wilson deployed two thousand troops to secure the streets. James Weldon Johnson certainly knew this. So his celebration of the black resistance seems like more than just an objective description of the events. It actually reads like a general prescription for black resistance against mobbing.69

Fig. 5.5. Portrait of James Weldon Johnson. (Black-and-white photoprints [Series 1], Scurlock Studio Records, ca. 1905–1994, Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution.)

In subsequent commentary, the Crisis extolled the enduring value of the black resistance in Washington, DC, in reporting about a black professor from Howard University who managed to find someone to sell him a house in a “restricted” area of the district. He was told to get out. When he refused, “his new home was given a battering.”

Horrified, his intellectual friends at the college “recommended to him some interesting court procedures.” But the militant professor and at least one of his colleagues pursued an alternate strategy. They “took the pains to build a barricade. One of them got his guns together and installed himself in the barricade. The two, fortified further by sandwiches and milk, quietly sat, watched and waited.”

Local veterans who had been active in defending the community during the 1919 riots got wind of these rough tactics and sent word that they would keep watch over the militant professor’s new home. Cause and effect are murky, but the reporting suggests that from this point, no further attacks occurred. The Crisis saw this as vindication. “The professor, using a rowdy principle, had opened up a new and decent area for Negro habitation. Thousands of fine Negroes live there now.”70

The disappointments and hazards of the early century fueled radical approaches to addressing the plight of black folk. Socialist A. Philip Randolph and Black Nationalist Marcus Garvey rejected any possibility of just treatment for Negroes in America. Disparate philosophies led to bitter personal attacks between Randolph, Garvey, and W. E. B Du Bois.

Randolph, a driving force in the rise of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, criticized that the NAACP was a tool of middle-class blacks. Randolph also split with Du Bois on the question of black service in World War I. Du Bois urged blacks to serve, arguing that by fighting they would earn their freedom. Randolph quipped that he would not fight to make the world safe for democracy but was more than willing to die at home to “make Georgia safe for the Negro.” Philosophical disagreement led to personal attack, with Randolph calling Du Bois a “handkerchief head . . . hat-in-hand Negro.”71

Marcus Garvey, who founded the Universal Negro Improvement Association in 1914 with the ambition of massive Negro migration to Africa, advanced a homegrown nationalist philosophy. Garvey castigated the NAACP as an organ of light-skinned, upper-class Negroes and leveled his own personal attack at Du Bois, charging that the rising intellectual leader of the race actually preferred the company of whites to blacks.

Returning the favor, Du Bois and Randolph expressed their disdain for Garvey’s gaudy showmanship openly and in print. Both the Crisis and Randolph’s signature publication, the Messenger, condemned Garvey and were sympathetic to established Negro leaders who reported mismanagement of Garvey’s Black Star shipping line to the federal government.72

But despite their deep philosophical differences and personal animus, these stalwarts of competing factions in the early freedom movement found agreement on the point of individual self-defense.73 There was, of course, disagreement about root causes of the perils to black folk. Randolph thought the plight of Negroes in America was rooted in capitalism, declaring that “lynching will not stop until Socialism comes.”74 Randolph saw no promise in legislation around the edges, warning, “Don’t be deceived by any capitalist bill to abolish lynching; if it becomes a law it would never be enforced. Have you not the Fourteenth Amendment which is supposed to protect your life, property and guarantee you the vote?”75 Randolph had a much broader assessment and a much grander plan:

No, lynching is not a domestic question, except in the rather domestic minds of Negro leaders, whose information is highly localized and domestic. The problems of the Negroes should be presented to every nation in the world and this sham democracy, about which American’s prate, should be exposed for what it is—a sham, a mockery, a rape on decency and a travesty on common sense. When lynching gets to be an international question, it will be the beginning of the end. On with the dance!76

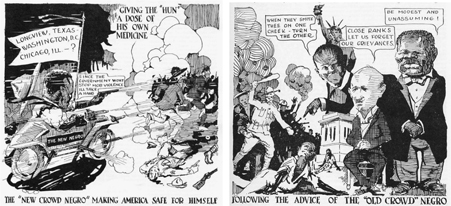

Fig. 5.6. Political cartoons from A. Phillip Randolph’s Messenger, proclaiming the militancy of the “New Crowd Negro” and criticizing W. E. B. Du Bois and the “Old Crowd.” (Left: “The ‘New Crowd Negro’ Making America Safe for Himself,” Messenger, 1919. Right: “Following the Advice of the ‘Old Crowd’ Negro,” Messenger, 1919.)

Acknowledging that his grand political agenda would take time, Randolph’s short-term remedy was reciprocal violence in self-defense. He reconciled this with a broader pacifism, explaining that pacifism controlled “only on matters that can be settled peacefully.” He did not equivocate about the legitimacy or utility of violence for people pressed to the wall, advising, “Always regard your own life as more important than the life of the person about to take yours, and if a choice has to be made between the sacrifice of your life and the loss of the lyncher’s life, choose to preserve your own and to destroy that of the lynching mob.”77 Randolph’s call resonated in the black press, even where people disagreed with his socialist agenda. The Kansas City Call celebrated Randolph’s appeal to self-defense as the battle cry of the “New Negro,” who was done “cringing” and was prepared to fight back.78

Marcus Garvey offered his own variation on the theme with a peculiar version of the traditional dichotomy between self-defense and political violence. Garvey openly advocated large-scale political violence, arguing that “all peoples have gained their freedom through organized force. . . . These are the means by which we as a race will climb to greatness.”79 Garvey’s hedge was that this violence would occur not in America or Europe but in Africa, where organized blacks would retake what was theirs.80

Fig. 5.7. Marcus Garvey (center) in full regalia. (Photograph by James VanDerZee, © Donna Mussenden VanDerZee, all rights reserved, Photographs and Prints Division, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, the New York Public Library.)

Domestically, Garvey embraced the traditional boundary against political violence, which he seemed to admit could not succeed in the United States. But on the point of private self-defense against imminent threats, Garvey was a traditionalist. Although he was roundly criticized for acknowledging common ground with the racially separatist KKK, Garvey also challenged the Klan, writing, “They can pull off their hot stuff in the south, but let them come north and touch Philadelphia, New York or Chicago and there will be little left of the Ku Klux Klan. . . . Let them try and come to Harlem and they will really have some fun.”81

Du Bois, Randolph, and Garvey embodied the early twentieth-century factions of the rising freedom movement. They were divided by profound philosophical differences. But on the basic point of personal security and response to the hazards that plagued Negroes, they found common ground. Harlem poet and Jamaican immigrant Claude McKay captured the general sentiment in a poem that circulated broadly in Randolph’s Messenger and was widely reprinted. It was a paean to Negro manhood that closes with this: “If we must die, let it not be like hogs, hunted and penned in an inglorious spot. . . . Like men we’ll face the murderous, cowardly pack, pressed to the wall, dying but fighting back.”

McKay was extolling and encouraging the fighting spirit of the New Negro. He might well have been celebrating the last violent stand of the Three Hundred at Thermopolis.82