In the spring of 1976, Maynard Holbrook Jackson, the first black mayor of Atlanta, urged the United States to “immediately ban the import, manufacture, sale and possession of all handguns.” It was a stark departure from the policy and practice of previous generations. The handgun is the quintessential self-defense tool and the black tradition of arms championed self-defense.1

Something plainly had changed, because Maynard Jackson was no lone voice in the wind. He was channeling the emerging orthodoxy of the bourgeoning black political class. Beyond his duties as mayor, Jackson chaired the National Coalition to Ban Handguns. He also was president of the Association of Local Black Elected Officials, which was populated by men like Gary, Indiana’s Richard Hatcher, one of the new crop of black mayors who rose on the tide of the civil-rights movement. When drug-trade fighting between old-line gangsters and rising black street gangs left twenty-two bodies on the streets of Gary in the span of a few weeks, Hatcher answered with a program of gun controls. Although it mattered little to the gangsters, Hatcher loudly declared that he would deny all future concealed-carry applications and invited objectors to take him to court. Appreciating the weakness of such local measures, black congressmen in Washington proposed national gun confiscation and a constitutional amendment repealing the right to keep and bear arms.2

This trend continues strongly into the current conversation. The National Urban League is a sustaining member of the Coalition to Stop Gun Violence, previously the National Coalition to Ban Handguns. In 2003, the NAACP sued gun manufacturers on the theory of tortiously “oversupplying” guns to black people. In 2007, Jesse Jackson was proudly arrested while protesting legal gun sales in the suburbs of Chicago. In 2008 and 2010, the NAACP filed amicus briefs to the United States Supreme Court, supporting blanket gun bans in Washington, DC, and Chicago. Losing those arguments, one of the association’s lawyers wrote in a prominent journal that recrafting the constitutional right to arms to allow targeted gun prohibition in black enclaves should be a core plank of the modern civil-rights agenda.3

So what happened? Certainly, many things have changed over the long development of the black tradition of arms. But three broad currents explain the dramatic shift to the modern orthodoxy of stringent gun control. First, as the modern civil-rights movement boiled over, black radicals undercut the core distinction that had sustained the black tradition of arms. By invoking self-defense as a justification for overt political violence, they forced black moderates, already buffeted by urban tumult, either to expend precious political capital to brace up the tradition of arms or to back away from it. Second, concurrent with the radicals’ apostasy, a strong black political class rose on the wave of a progressive coalition. The newly minted national gun-control movement rested firmly within that coalition and captured the allegiance of the rising black political class, who now faced the challenge of actually governing their recently won domains. Third, as black-on-black gun violence commanded increasing attention, gun bans promised a solution with the compelling logic of no guns equals no gun crime. These three currents explain how, in less than a decade, the robust black tradition of arms was supplanted by the modern orthodoxy of stringent supply controls.

The modern orthodoxy grows from a particular strand of civil-rights advocacy and political strategy that prevailed over competing approaches within the modern freedom movement. By the 1960s, the NAACP, the National Urban League, the SCLC, SNCC, and CORE (the “big five”) vied for influence and funding. Out of that mix, the moderate, integrationist NAACP and National Urban League model, capitalizing on coalitions with white progressives, emerged as the dominant form. This triumph was substantially a consequence of the radicalization of the competing organizations.4

There was evidence of the divide fairly early on. SNCC and CORE took a more militant path and were viewed as troublemakers by the Kennedy administration. According to one source, John F. Kennedy was pleased that the SCLC rather than SNCC was leading the 1963 desegregation campaign in Birmingham. Kennedy woefully concluded that the “SNCC has got an investment in violence.” Contrasting philosophies also were evident in the responses to Lyndon Johnson’s request for suspension of demonstrations during the 1964 presidential elections. The NAACP, the SCLC and the National Urban League all granted President Johnson’s request in support of his reelection efforts. SNCC and CORE refused.5

By 1966, both CORE and SNCC had flirted with violence as a political tactic in the struggle to achieve civil and human rights.6 CORE, a formally interracial organization founded on Gandhian principles of nonviolence, whose members and leadership were predominately white well into the 1960s, transformed into an almost entirely black organization that threw off its pacifist constraints. SNCC became racially exclusive during the 1966 Atlanta Project. SNCC leaders Stokely Carmichael and H. Rap Brown became more widely known as part of the Black Power movement.7

Ultra-radicals like the Black Panthers obliterated traditional boundaries, invoking self-defense as a justification for political violence and confirming the generations-old worry that the approach would trigger overwhelming backlash. This was a tipping point in the development of the modern orthodoxy.8 The risk of spillover from self-defense into political violence had always shadowed the black tradition of arms. But now radicals upended the distinction.9 Although some argue that the radicals unwittingly strengthened the hand of moderates, the sharp downward trajectory of the radical organizations shows that political violence as a direct strategy was a failure. The Black Panther Party is emblematic.10

Initially designated the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense, the Panthers pushed political violence under the umbrella of self-defense to justify the kinds of tactics that Panther leader Eldridge Cleaver described in the wake of Martin Luther King’s assassination. “We put together a little series of events to take place that next night, where we basically went out to ambush the cops. But it was an aborted ambush because the cops showed up too soon.” The interruption did not prevent Cleaver and his accomplices from firing nine shots at Officer Richard Jensen, who pulled up as they were loading into vehicles on the way to the ambush site.

The Panthers’ blazing downward arc confirmed long-standing fears. The group was decimated by federal, state, and local responses to its open campaign of political violence. Confrontations with the state led to incarceration and deaths of party members. Huey Newton later acknowledged that political violence was counterproductive and launched the Panthers into an unwinnable war with the state that destroyed their outside support.11 But in 1967, Newton was insistent, “If I’m talking about self-defense, I’m talking about politics; if I’m talking about politics, I’m talking about self-defense. You can’t separate them.”12 Writing in the Panthers’ weekly newspaper, one member was even more graphic, claiming that “sniping, stabbing, bombing, etc. . . . can only be defined correctly as self-defense.”13

Splinter groups like the Black Liberation Army were equally extreme advocates and practitioners of political violence under the banner of self-defense. The BLA urged political warfare through the killing of police, both black and white. They claimed credit for the murder of at least two policemen at a Harlem housing project and for the attempted murder of two others who were guarding the home of a lawyer who was prosecuting black revolutionary organizations.14

The Revolutionary Action Movement (RAM), which rose to infamy after a bungled attempt to blow up the Statue of Liberty, seemed to recognize no boundaries at all in its plot to kill NAACP head Roy Wilkins. They planned to blame the killing on white assassins with the hope of provoking a race war. The conspiracy fizzled. But testimony in the subsequent prosecution exposed a shocking ruthlessness. Discussing how to respond if Wilkins was with his wife, the triggermen resolved, “We will just have to burn him in her presence.”15

Official response to the radicals confirmed long assessments of the folly of political violence. From 1966 through 1967, shootouts with police left a line of Black Panthers dead, wounded, and imprisoned. The BLA and RAM withered under similar pressures.16

This period is crucial in the development of the modern orthodoxy. Radical organizations were in decline. Urban riots marked a failure of the traditional civil-rights leadership to harness the energy that fueled the violence. Roy Wilkins recounts how “Dr. King was practically run out of Watts when he went to California to see what was going on. . . . Dr. King and the rest of us suddenly found ourselves in the middle of a two-front war. In one direction we had to keep the South from making a Jim Crow comeback in Congress; in the other we had to do something about the ghettos in the cities. No one was really prepared with a strategy or a workable program. We seemed more and more often to fall out among ourselves.”17

Burning cities drained black political capital, fueled white backlash, and pressed moderate blacks more firmly into the camp of progressive allies. In this environment, it was politically treacherous for moderates to defend the black tradition of arms. When radicals defied the boundary against political violence, more conservative organizations had little to gain by stepping in to repair the damage. Even the attempt would risk the perception of agreement with the radicals, and that would threaten crucial alliances with white progressives. So the voices of moderation—the rising political class and the NAACP, which had cut its organizational teeth defending Negroes who protected themselves with guns—backed away from the generations-old tradition of arms.

There is an early marker of this in 1966. On August 16, representatives from along the spectrum of black politics appeared on the nationally syndicated political talk show Meet the Press to address the newly minted slogan “Black Power.” It was a high-profile airing of the radical attack on the boundary against political violence.

Opposing the militant implications of Black Power were Martin Luther King of the SCLC, Roy Wilkins of the NAACP, and Whitney Young of the National Urban League. Defending it were James Meredith and Stokely Carmichael of SNCC and Floyd McKissick of CORE. Carmichael is generally credited with launching the phrase in June 1966 in a Greenwood, Mississippi, speech, marking resumption of the March against Fear.18

Host Lawrence Spivak’s opening to Floyd McKissick was an opportunity for the new director of CORE to affirm his commitment to the boundary against political violence. “There is a difference,” said Spivak, “between self-defense and non-violence. . . . Everybody believes in self-defense. . . . Am I to understand then that you and Dr. Martin Luther King really are not in disagreement on [this]?” McKissick responded that self-defense and nonviolence are “not incompatible,” but he equivocated on whether he agreed with King.

Unable to draw a direct answer from McKissick, the panel put the question to King, whose cautious response reflected the circumstances. Recall King’s solid embrace of self-defense in the Robert Williams controversy as “moral,” “legal,” and a signal of black “courage and self-respect.” Now, in the shadow of radical invocations of Black Power, King offered a barely recognizable rendition of the structure he had articulated in the Williams debate and steered hard away from the boundary against political violence. Here is King:

I believe firmly in nonviolence. . . . I think a turn to violence on the part of the Negro at this time would be both impractical and immoral. . . . If Mr. McKissick believes in that, I certainly agree with him. On the question of defensive violence, I have made it clear that I don’t think we need programmatic action around defensive violence. People are going to defend themselves anyway. I think the minute you have programmatic action around defensive violence and pronouncements about it, the line of demarcation between defensive violence and aggressive violence becomes very thin. The minute the nomenclature of violence gets into the atmosphere, people begin to respond violently and in their unsophisticated minds they cannot quite make the distinction between defensive and aggressive violence. [Emphasis added.]

Spivak pressed the political violence boundary again in an exchange with James Meredith. The result was a raw, open endorsement of political violence that obliterated the traditional boundary. Referencing Meredith’s criticisms of King, Spivak asked,

Mr. Meredith, don’t you think we ought to get straight on the difference between non-violence and self-defense? . . . I think that when Dr. King and others speak about nonviolence they say that groups of Negroes shouldn’t take to arms. . . . I don’t think that there are many of us who don’t believe in the right of self-defense of any Negro against anyone who attacks him. . . . When we talk about non-violence, we are saying that the Negro ought not in groups or alone take up a gun . . . in order to take what he believes belongs to him.

Meredith, perhaps still nursing his gunshot wounds, plunged headlong into forbidden territory.

MEREDITH: The Negro has never entertained the idea of taking up arms against the whites. . . . But now I think the Negro must become part of this mainstream, and if the whites— now in you take Mississippi, for instance—I know the people who shot in my home years ago. They know the people that killed all of the Negroes that have been killed. . . . The Negro has no choice but to remove these men, and they have to be removed.

SPIVAK: Are you suggesting then that if several Negroes are killed or any white men are killed and the law does not punish them, as happens very often in the case of white men too, that people ought to organize as vigilantes and go out and take the law into their own hands and commit violence? You are not saying that, are you Mr. Meredith?

MEREDITH: That is exactly what I am saying. Exactly. [Emphasis added.]

CARMICHAEL: If you don’t want us to do it, who is going to going to do it?

. . .

SPIVAK: Mr. Meredith, do you mean to tell me that you believe Negroes in this country ought to organize, take up guns?

MEREDITH: This is precisely, I will tell you why, because the white supremacy is a system.

SPIVAK: Mr. Meredith, this doesn’t even make sense against 180 million people. If you do it, they are going to do it.

. . .

CARL ROWAN: Mr. Carmichael, do I detect that you agree with Mr. Meredith that the Negro may have to take up arms.

CARMICHAEL: . . . I agree 150 percent that black people have to move to the position where they organize themselves and they are in fact a protection for each other. . . . If in fact 180 million people just think they are going to turn on us and we are going to sit there, like the Nazis did to the Jews, they are wrong. We are going to go down together, all of us.

ROWLAND EVANS: Mr. Wilkins, I want to ask you [about Carmichael’s] last statement, do you think it serves the Negro or the white man, his purpose in any way to threaten that the ten percent of the Negro population can, if it has to, drag down this whole country?

. . .

WILKINS: I think Mr. Carmichael—if he weren’t where he is, he ought to be on Madison Avenue. He is a public relations man par excellence. He abounds in the provocative phrase. Of course, no one believes that the Negro minority in this country is going to take up arms and try to rectify every wrong that has been done [to] the Negro race if somebody doesn’t rectify it through the regular channels.19

It is easy to understand how in this environment, the conservative leadership became more circumspect about explaining or excusing black violence, even in self-defense. The distinction between self-defense and political violence was always slippery, and cautious players gave the boundary-land berth. Now, amidst the radicals’ chants of Black Power, prudence demanded extreme caution in the treatment of any sort of violence.

For Roy Wilkins, some have argued, the approach had broader strategic implications. Critics point to Wilkins’s widely circulated fundraising letter denouncing the Black Power movement while underscoring the NAACP’s continued support of integration and nonviolence. Donations to the NAACP quadrupled during 1966 to 1968 when he was vigorously opposing radical cries for Black Power.20

Wilkins always denied the accusation that he exploited the fears of Black Power and defended his record in a fashion that rested soundly on the long black tradition of arms. “For 60 years,” Wilkins reminded, “the NAACP has asserted the right of Negroes to self-defense against the violence of white oppression. During the Parker affair in the thirties, in the elections of 1948 and 1960s, Negroes have amply shown how aware they were of their own political power. None of these things was new. The younger people were either ignorant of the long record or they chose to ignore it.”21

Years later, looking back on that time, Wilkins framed the question as,

whether [the new radicals] were after a revolution. I always believed that for American Negroes revolutionary fantasies were suicidal. To oppose revolution did not mean to fear whites; I knew that anyone who was not cautious in leading a one-tenth minority into a conflict with an overwhelming majority was a fool. You can force a lion one way when you have real artillery, but when you have a powder puff you have to handle yourself differently—if you want to keep your people alive. For all [the radicals’] reckless talk of guns and power back then, I still don’t think [they] could tell the difference between a pistol and a powder puff.22

Whatever his motivation, Roy Wilkins plainly opposed the radical formulation of political violence as self-defense. Still, in other venues, he continued rhetorical support of a careful, conservative version of the black tradition of arms. In his keynote address at the 1966 NAACP convention, Wilkins both endorsed traditional self-defense and repudiated the radical agenda:

One organization [CORE] which has been meeting in Baltimore has passed a resolution declaring for defense of themselves by Negro citizens if they are attacked. This is not new as far as the NAACP is concerned. Historically our association has defended in court those persons who have defended themselves and their homes with firearms. . . . But the more serious division in the civil rights movement is the one posed by a word formulation that implies clearly a difference in goals. No matter how endlessly they try to explain it, the term “black power” means anti-white power. . . . It has to mean separatism. . . . It is a reverse Mississippi, a reverse Hitler, a reverse Ku Klux Klan. . . .

We of the NAACP will have none of this.23

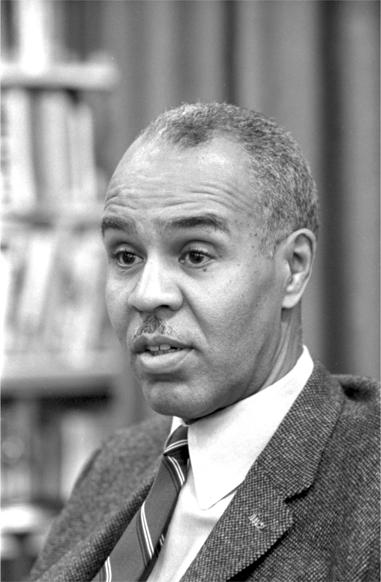

Fig. 8.1. Roy Wilkins in the 1960s. (Photograph by Warren K. Leffler, April 5, 1963, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.)

Martin Luther King displayed his own objection to CORE’s radical turn and the Black Power rhetoric by refusing to attend CORE’s 1966 convention. King also criticized SNCC radicals, arguing that talk of retaliatory violence failed to appreciate that “the black man needs the white man and the white man needs the black man.”24

This was an important moment of converging trends. While the radical strategy of political violence as self-defense would soon flame out, coalition politics and the conservative strategy of institutional change within the system were paying off. CORE, SNCC, and even the SCLC (laboring under King’s antiwar stance) experienced a decline in external support. The NAACP, on the other hand, enjoyed a substantial increase in outside funding. For many who wanted to support the movement, the NAACP was, increasingly, the only acceptable option.

Important institutional changes were also unfolding. President Lyndon Johnson advanced the War on Poverty with spoils to the black underclass. He pressed for and signed landmark civil-rights legislation and appointed the first black, Thurgood Marshall, to the post of solicitor general and then to the United States Supreme Court. In preparation for Marshall’s confirmation hearings, Johnson put him on a national commission to study crime and violence in American cities. “The idea was to keep Marshall’s name in the news as a sober, rational voice able to respond to black militants.”25 Adding to the list of firsts, Johnson appointed the first-ever black cabinet officer, Robert Weaver, as secretary of Housing and Urban Development and sent black ambassadors to Finland and Luxembourg.

Within this whirlwind of black advancement, Johnson also signed the 1968 Gun Control Act, six months after the gusher of violence that followed Martin Luther King’s April 4 death by gunshot. The timing and meager substance of the law left one prominent liberal skeptic to charge that the Gun Control Act was more a reflex against black violence than a well-considered policy. Among the act’s most significant restrictions were import limits on small, cheap handguns derided as “Saturday Night Specials”—a label that combined references to cheap little guns dubbed “Suicide Specials” and the tumult of “Niggertown Saturday Night.”26

One of the first evident moves in the tip over to the modern orthodoxy occurred in Roy Wilkins’s allusion in 1967 to the ongoing work driving the 1968 Gun Control Act. In questioning reflecting the critique that the act was substantially a reflex against black violence, Wilkins, on another Meet the Press appearance, was asked by Robert Novak, “Would you be in favor of a massive effort to disarm the Negroes in the ghettoes, just to try to prevent these open-shooting wars such as occurred in Newark last night?” Wilkins’s principle response tracked the long tradition of arms. “I wouldn’t disarm the Negroes and leave them helpless prey to the people who wanted to go in and shoot them up. . . . Every American wants to own a rifle. Why shouldn’t the Negroes own rifles?”

This is a staunchly pro-gun statement, but this was not all that Wilkins said. In a fashion that recalls his 1936 criticism of the killing of William and Cora Wales, Wilkins’s first parry actually cut the other way and shows a nascent support for the program of supply-side gun controls that was gaining traction among progressives. Before standing up for the interests of Negroes to own rifles, Wilkins said, “I would be in favor of disarming everybody, not just the Negroes.”27 It is unclear whether Wilkins was referring to nationwide disarmament or disarming everyone in riot-torn cities. Either way, the statement is in tension with the NAACP’s long support of armed self-defense and is an early signal of movement toward a stringent gun-control agenda.

Moving into the 1970s, as blacks registered to vote in greater numbers, more black representatives were elected to legislatures. Blacks gained increasingly influential positions in the executive branch, and black administrations came to power in various cities. Even in little Fayette, Mississippi, where a restaurant still thrived on Main Street exhibiting a sign warning, “Every cent spent by a nigger to be donated to the Ku Klux Klan,” Charles Evers defeated “Turnip Green” Allen to become the town’s first black mayor. Once installed, Mayor Evers adopted a common approach of newly minted black bureaucrats and implemented a ban on the concealed carry of firearms.28

This emerging black political class faced a new reality. Products of successful coalition politics and beneficiaries of legislation forged by progressive alliances, they disconnected from the tradition of armed self-defense that was now sullied by the radicals’ blurring of the boundary against political violence. With access to new fields of power, the growing political class now could plausibly view the historic reasons for blacks’ distrusting the state to protect them as having faded with their own ascendency to power.

This is precisely the time that the national gun-control movement emerged and was quickly ensconced in the progressive coalition. With cities burning and black radicals bent on revolution, politicians and editorialists called for stricter gun legislation. Black mayors and local, state, and national representatives and appointees—having gained power, and now facing the burden of exercising it—embraced the progressive program of supply-side gun control as an answer to the crime and unrest afflicting their new domains.

From here, the modern orthodoxy took hold and flourished as supply-side gun control became an article of faith for progressives. Today, the worry that this demands a level of trust and dependency on government that is incompatible with the black experience is answered with the assertion that “things have changed.” And considering the toll that gun crime takes on the black community, we are tempted to conclude that the “things have changed” assessment fully explains and justifies the modern orthodoxy.

But on closer analysis, even stipulating that racist violence and the malevolent state are now nominal concerns (what to do though, with sporadic modern episodes that jolt us back to a darker time?29), the “things have changed” assessment raises a series of unexamined questions. Consider, for example, the tacit assumptions about black-on-black crime. This scourge, perpetrated largely by desperate, young, urban men and boys, prompts many to embrace the promise of supply-side gun control. But is this really a new variable that easily explains the shift to the modern orthodoxy? What if it turns out that the black tradition of arms always has required the balancing of violence among the criminal microculture against the self-defense interests of good people? If so, how should we strike that balance today, where some might dismiss the counterweight of self-defense against racist terrorism as a faded concern of an earlier age. And is that even the right balance? Does the tradition of arms just dissolve with the sense that the complexion and character of criminal threats has changed? What about good people in distressed communities who want guns to defend themselves against the predators in their midst?

Wading into these concerns sends us to the root of the black tradition of arms and the realization that the tradition is only incidentally an outgrowth of America’s racist past. Fundamentally, the tradition rests on universal principles of self-defense. Those principles are a basic response to structural state failure within the hard boundaries of physics—episodes of imminent violence where it is impossible for the government to act.30 It is true that the black tradition of arms evolved in a context where state failure was often pernicious. But from the perspective of people at risk, the reason for state failure matters little.31

More than a century ago, T. Thomas Fortune urged, “in the absence of law . . . we maintain that every individual has every right . . . to protect himself.”32 Ida B. Wells advocated armed self-defense as a response to government failure, noting the folly of trusting the government “that gave Blacks the ballot, to be strong enough to protect the exercise of that ballot.”33 Wells championed the Winchester repeating rifle on the view that even if the federal government was not overtly hostile, it was not equipped to protect blacks from imminent threats. W. E. B. Du Bois operated on the same impulse, wielding a shotgun to protect his home and family, with a clear appreciation that, for some undetermined period, he was on his own.

A century later, Shelly Parker in Washington, DC, and Otis McDonald in Chicago were similarly besieged. The difference was that their tormentors were not racist terrorists but young black thugs and drug criminals. Within a specific window of risk, they also were on their own against looming threats. We do not begrudge earlier generations of black folk their guns, and their grit might even raise a patch of prideful gooseflesh. But Shelly Parker and Otis McDonald, under the full weight of the modern orthodoxy and over the objection of America’s leading civil-rights organization, required intervention by the United States Supreme Court to validate their right to armed self-defense.

Some found it perplexing that when the Court affirmed the individual right to arms, the litigation was fueled by these black plaintiffs. Were they serious? Were they dupes? The answer is that Shelly Parker and Otis McDonald, laboring under the two most restrictive gun-control regimes in the country, were just seeking what generations of black folk before them had sought in response to an array of threats. They wanted access to tools that might give them some additional chance of escaping or defeating violent attackers who were on them before help could arrive.

Standing solidly on the black tradition of arms, Otis McDonald and Shelly Parker agitated through the courts in separate civil-rights challenges, seeking access to handguns to combat threats primarily from a slim criminal microculture of young black men. And that, in a nutshell, fuels the hard questions about the current implications of the black tradition of arms.

How then should the complexion of the threats to the lives and safety of innocents like Shelley Parker and Otis McDonald affect our assessment of supply-side gun-control policies that ground the modern orthodoxy? People must do their own thinking about this. But we all are constrained by the basic inputs. The next chapter details those variables.