Chapter 7

Reading Comprehension is the only question type that appears on all major standardized tests, and with good reason. No matter what academic discipline you pursue, making sense of densely written material is a core skill necessary for success in graduate school. That’s why Reading Comprehension passages are on the GRE—to test this skill. Fittingly, ETS adapts its content from actual, graduate-level documents. The GRE traditionally takes its topics from four disciplines: social sciences, biological sciences, physical sciences, and the arts and humanities.

There are roughly 10 reading passages and 20 questions spread between the two Verbal Reasoning sections of the GRE. Some passages are only one paragraph in length, while others are longer. Each passage is then followed by one to six questions that will require you to perform one or more of the following skills: ascertain a passage’s scope and purpose, consider what inferences can properly be drawn from the statements in a passage, research details in the text, understand the meaning of words and the function of sentences in context, and analyze the assumptions inherent in an argument.

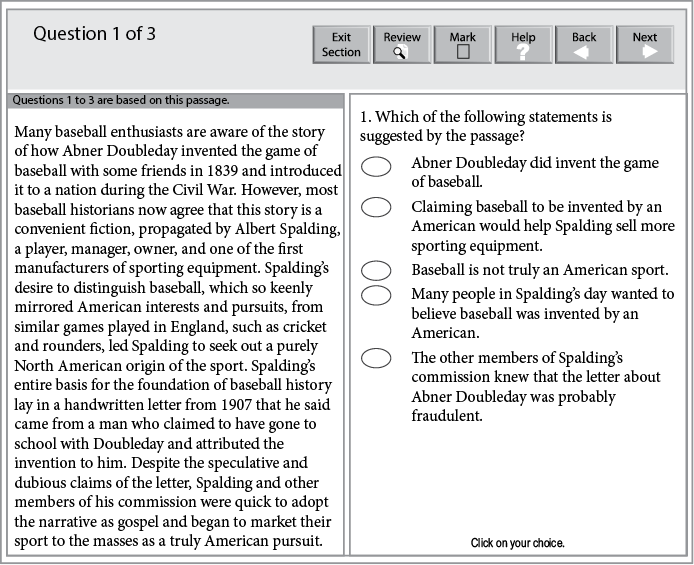

Because the number of questions for each passage varies, there will always be a sentence introducing the passage that tells you exactly how many questions are associated with the passage. Here is an example of an introductory sentence and the passage that follows; these appear on the left of your screen. The first question about the passage also appears, on the right.

Reading Comprehension questions take one of three forms. The first, and most familiar, is the standard multiple-choice question. A question of this type will ask you to select the best answer from a set of five possible answers. The question shown above is a multiple-choice question.

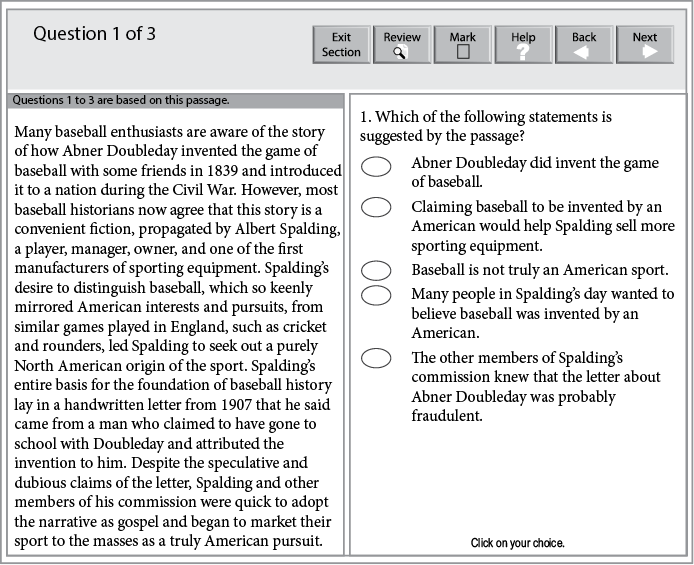

The second type of question will present you with three answer choices, of which one or more are correct. Note the language in the box above the question stem: “Consider each of the choices separately and select all that apply.” In these all-that-apply questions, you will not receive partial credit for selecting only some of the right answers—you must select all of the correct choices, and no incorrect ones, to receive full credit for the question. Here’s an example:

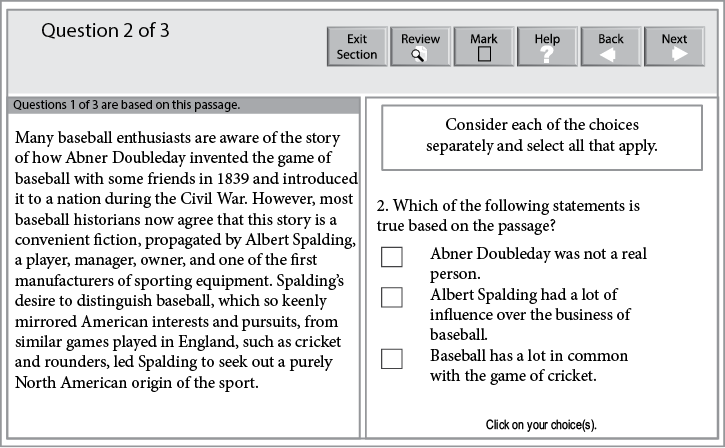

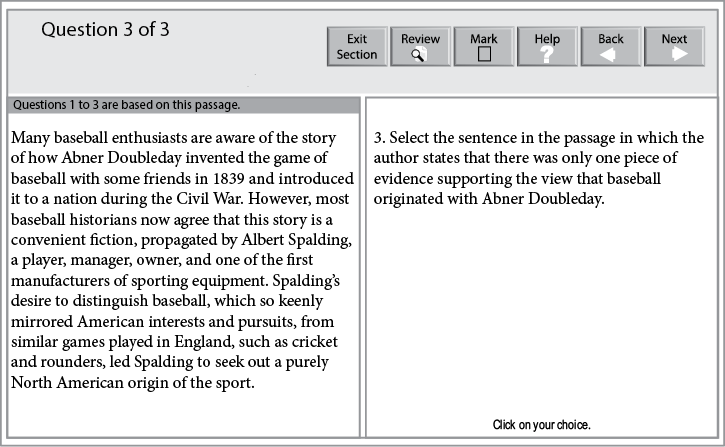

Finally, a third type of question asks you to find and then select within the passage a sentence that includes an important detail or that performs a certain function. In these select-in-passage questions, you will use your mouse to click on the sentence that specifically fulfills the task set out in the question stem. Here is an example of a select-in-passage question:

Note: When a passage has just one question associated with it, Steps 1 and 2 are switched; read the question stem first, then read the passage.

As noted in Chapter 4: Verbal Foundations, many students think that because they have read a large number of academic texts for college classes, they can apply the same skills to achieve success on the GRE. However, answering Reading Comprehension questions correctly requires a different approach.

In school, you read to learn things about a subject. However, if a GRE passage is about the behavior of enzymes, you are not taking a biology test, and if it is about the influence of Appalachian music on composer Aaron Copland’s work, you are not taking a music theory test. The makers of the GRE are not testing your subject knowledge; rather, they are interested in your critical thinking skills. Moreover, GRE Reading Comprehension questions are open-book—the passage stays on the screen throughout the question set, meaning that if a question asks about a detail, you can research it in the passage. Thus, memorizing details as you read is wasted effort. In fact, answering Detail questions from memory often leads to the wrong answer because the GRE supplies incorrect answer choices that are subtle distortions of passage content. The GRE wants to know whether you can grasp the overall structure of a passage so you can efficiently look up information you need to answer a question—a skill you’ll use when completing papers and projects in graduate school—and it rewards test takers who use this approach.

Instead of reading to learn the material, focus on the big picture: Why did the author write the passage, and what are the passage’s topic and scope? Sifting out these big-picture concepts from the surrounding details—reading strategically—is the key to success.

But reading strategically is only part of the battle. After all, you don’t get any points for reading well. Instead, your goal is to answer questions correctly. And to answer Reading Comprehension questions correctly, you need to know the specific task a question asks you to perform, how to accomplish that task effectively, and how to avoid the GRE’s common and predictable wrong-answer traps.

If learning a new way to read passages and answer questions seems daunting, don’t worry. The GRE is a standardized test, and that means that the passages and questions in every Reading Comprehension section follow the same predictable patterns, over and over again. Success in the Reading Comprehension section, then, is simply a result of mastering a small handful of skills, including the ability to read the passage strategically, research the passage or your notes on the passage to answer specific questions, make clear predictions, and know what differentiates right answers from wrong answers. Those skills are intimately tied to the Kaplan Method for Reading Comprehension, a step-by-step approach that will help you maximize your performance in this section.

STEP 1

STEP 1Note that this step is not simply “Read the passage.” Step 1 is to read strategically. Reading strategically means giving more weight to some parts of the passage than to others.

That means that as you read, you will make sure to fully understand certain parts of the passage (things like the author’s opinion, each paragraph’s main idea, new theories, interesting discoveries) and read lightly through parts of the passage that are not as important (background information, supporting examples, rhetorical asides). Doing this will help you read efficiently while still capturing the important big-picture information that you’ll need to answer questions. Noting the big-picture information means identifying the topic, scope, and purpose of a passage. The topic is what the passage is about, very broadly stated. The scope is that specific aspect of the topic that interests the author. The purpose is the author’s reason for writing the passage.

On the GRE, authors write passages for the following reasons:

Here are some examples of big-picture summaries. Try to imagine the passage that each of these reflects.

|

|

|

Just from knowing the topic, scope, and purpose, you probably find that you have a pretty good grasp of the gist of these passages, without even having read them. When you capture this information from a passage you read, you will have a solid foundation to answer GRE Reading Comprehension questions.

In addition, part of strategic reading is taking notes on the passage, or making a passage map. This means writing down the topic, scope, and purpose, as in the examples above, as well as the following information:

Your goal is not to rewrite the passage. After all, the passage is always going to be there on the screen, and writing down too much information would take too much time. Instead, in addition to mentally paraphrasing as you read, summarize important concepts and opinions, as well as terms and examples that are central to the author’s main idea, by jotting down a few words on your scratch paper. You can and should use abbreviations and symbols, and sometimes a quick sketch will capture a concept more quickly and succinctly than words. Finally, no one will ever read this except you, so it doesn’t need to be neat; as long as you understand what you’ve written, your passage map is doing its job.

One question that many students have initially is: How do I know what’s important in a passage? Fortunately, GRE passages will tell you what’s important with keywords—including the same kind of keywords you are already familiar with from Text Completion and Sentence Equivalence questions. Particularly important are keywords of emphasis and of contrast. Emphasis keywords (such as very, important, and clearly) are strong adjectives or adverbs that highlight the author’s opinion or an idea the author views as significant or noteworthy. Contrast keywords (such as but, yet, and however) often indicate a significant conflict, disagreement, or change in thinking.

When you strategically read a Reading Comprehension passage, you determine the passage’s big picture: the passage’s topic, scope, and purpose. The GRE provides savvy readers with keywords as clues to when to slow down and digest important parts of a passage and when to move quickly past unimportant details. Take a look at the following sentences:

Based on these two sentences, can you infer the contents of Dr. Robinson’s lecture or its value to the students? Without keywords indicating the relationship between the sentences, you simply cannot determine what Dr. Robinson spoke about or whether the students learned anything. But add just one little phrase to the beginning of the second sentence, and a deduction can be made:

Now it’s clear: the students gained their understanding of global currency exchange rates because they attended Dr. Robinson’s lecture. But what if you saw this phrasing instead?

In this instance, either Dr. Robinson didn’t cover the topic of global currency exchange rates, or he did so inadequately. Either way, it’s apparent that the students gained their knowledge of global currency exchange rates from some other source.

Here are the different types of keywords that will help you locate central ideas and opinions and grasp the structure of the passage:

Of course, you don’t get any points on the GRE for classifying a keyword or for writing down a note on your scratch paper. Instead, the purpose of focusing on keywords is to identify those parts of the passage that help you understand its big picture while at the same time ignoring less important details. Keywords also help you take control over your reading by helping you predict the function of the text that follows. Imagine that you saw a passage with the following structure on Test Day. Can you anticipate the kinds of details that would fill each of the blanks?

The emphasis keyword “exceptionally” tells you that the author believes the northern rabbit’s adaptation to cold climates is significant, and you can expect the following text to focus on this idea. The evidence keyword “because” indicates the author will provide a reason the rabbit survives the cold so well. “Moreover,” a continuation keyword, signals another reason. Then the contrast keyword “[h]owever” indicates a change in direction, so the next two blanks will include text describing potential threats to the northern rabbit’s survival. While you can’t predict the exact features that aid the rabbit (a special type of insulating fur? hibernation strategies?) or the specific dangers it faces (cold-climate predators? lack of food in the winter?), you do understand the overall structure of the passage. The details might change, but as long as the keywords remain the same, the overall gist of the passage does not. You actually know a lot about this passage just from the outline above, without any details!

Are keywords just as helpful when the passage begins discussing ideas and terms that you’re unfamiliar with?

This passage, like the one before it, is a scientific passage with a species of animal as the topic. However, the text is denser, and the terms the author uses—“certain types of facial cancers” and “lack of genetic diversity”—might throw off some untrained test takers who focus too much on details about the topic and not on the passage’s overall structure. A well-trained test taker knows that “these scientists” will base their conclusions on data that show a connection between the concepts in the first sentence. As the expert reads, she knows that what follows “[h]owever” will introduce ideas that differ from those of “many biologists.” By focusing on keywords, the expert knows to expect that the “new research” will present an alternative cause of the facial cancer. Furthermore, by starting a sentence with “In fact,” the author may be signaling his own opinion on the matter—stating something he believes to be the truth. Again, simply on the basis of the outline above, you already know the gist of the passage.

With each GRE Reading Comprehension passage, focus on keywords to help you separate unimportant background information from the author’s topic, scope, and purpose in writing, and to help you grasp the structure of the passage. Again, because the passage remains on screen as you answer the questions, you will be able to research details as necessary. In this way, you will read efficiently and be well prepared to answer questions correctly.

Note: When a passage has just one question associated with it, Steps 1 and 2 are switched; read the question stem first, then read the passage.

STEP 2

STEP 2Once you have strategically read a passage to determine its topic, scope, and purpose and make a passage map, it is time to start answering the questions. Luckily, because the GRE is a standardized test, the questions that accompany a passage almost always fall into one of just a handful of categories:

Global. These ask about the passage as a whole. Look for language in the question stem that asks you to determine a passage’s main idea, primary purpose, or overall structure. Here are some examples of Global question stems:

Which of the following most accurately describes the primary purpose of the passage?

The author’s tone could best be described as

Detail. These ask you to research the text and identify a specific detail mentioned in the passage. Look for language in the question stem such as “according to the author” or “is mentioned in the passage.” Here are some examples of Detail question stems:

According the passage, the primary cause of unemployment in micronations is a lack of

Which of the following was mentioned in the passage as a result of high employment?

Inference. These questions ask for something that, though not stated explicitly in the text, must be true based on the information that is provide in the passage. Look for language in the question stem like “suggests,” “implies,” or “most likely agrees.” Here are some examples of Inference question stems:

The passage most strongly suggests that which of the following is true?

With which of the following characterizations of medieval comedies would the author most likely agree?

Logic. This type of question asks you to describe why the author included a certain word, phrase, or statement. Look for language like “in order to” or “primarily serves to.” Here are some examples of Logic question stems:

The author mentions Tussey’s theory of copyright systems primarily in order to

Which of the following most accurately describes the reason the author included the results of the experiments in lines 9–12?

Vocab-in-Context. These relatively straightforward questions ask you to identify the specific way a word is used in the passage. Here are some examples of Vocab-in-Context questions:

As it is used in line 16, “brilliant” most nearly means

Which of the following most closely corresponds to the meaning of the word “effect” as it is used in line 26?

Reasoning. These questions ask you to analyze an author’s reasoning in an argument. They may ask you to identify an argument’s assumption, point out a flaw in the author’s reasoning, or strengthen or weaken the reasoning. Here are some examples of Reasoning questions:

The ethicist’s argument requires the assumption that

Which of the following would cast the most doubt on the conclusion drawn by the scholar?

Now be honest: Did you just skim through that list of question types without taking the time to catalog and understand how the tasks are different? If you did, you’re not alone. But take another look. The fact is, knowing the type of question you’re dealing with is incredibly helpful. For one thing, different question types require different research and prediction steps. For another, different question types have different types of flawed answer choices, which you can learn to avoid. Knowing how to research a question effectively and how to avoid wrong answer traps will allow you to choose correct answers confidently and improve your performance.

In the following exercise, identify each question as one of the following types: Global, Detail, Inference, Logic, Vocab-in-Context, or Reasoning. In addition, for each example question, ask yourself:

The pages following this drill will provide answers and explanations to these questions.

The passage implies which of the following about [xxxxx]?

According to the passage, each of the following is true about [xxxxx] EXCEPT

The author mentions [xxxxx] in order to

The main point of the passage is

Which of the following most accurately describes a flaw in the argument above?

As it is used in context, the word “[xxxxx]” in line 17 most nearly means

An appropriate title for the passage would be

The author makes which of the following statements concerning [xxxxx]?

The passage provides support for which of the following assertions about [xxxxx]?

Which of the following best supports the author’s conclusion that [xxxxx]?

The function of the example in line xx is to

The author indicates explicitly that which of the following has been [xxxxx]?

When you see “implies” or “suggests” in a question stem, you’re dealing with an Inference question.

Language that points you to find something directly stated in the passage (here, the phrase “according to the passage”) indicates a Detail question.

The phrase “in order to” means that this is a Logic question. Your task is to determine why the author has included the specific phrase or statement.

This is a Global question that asks for the entire passage’s main point.

To answer this Reasoning question, separate the argument’s conclusion from its evidence and then describe the way in which the evidence fails to fully support the conclusion.

This is clearly a Vocab-In-Context question.

Since the title of a passage reflects the content of the passage as a whole, this is a Global question.

Since the question asks for a specific statement made by the author, this is a Detail question.

The correct answer will be something that can be directly inferred from information in the passage.

This is a Reasoning question because the answer will support the conclusion. Notice that the word “support” is used differently than in the previous question. In this question, the answer strengthens (supports) the conclusion in the passage; in the prior question, the passage supported the answer.

This is a Logic question. It is asking what role the example plays in the passage, not for information or an inference about the example.

The word “explicitly” means that the question deals with something that is contained in the passage, not something that needs to be inferred. How did you do? Were you able to correctly identify each question’s type? How would you have proceeded differently to answer each of the different types of questions? It is easy to overlook the value of identifying question types in the Reading Comprehension section. However, knowing the type of question you’re dealing with will help you research the passage more effectively. That, in turn, will help you more quickly formulate a prediction and more quickly find the correct answer.

STEP 3

STEP 3Once you have analyzed and fully understood the question stem, use your passage map for guidance. Global questions and some Inference and Logic questions are so general that you can simply use your understanding of the passage’s topic, scope, and purpose as well as the structure of the passage to answer them. You can answer questions such as “What is the purpose of this passage?” or “Which of these statements expresses the author’s conclusion?” directly from your notes.

Sometimes, however, the question stem will ask you to find a specific detail in the passage, draw an inference about a specific situation mentioned by the author, or identify the function of a specific phrase or sentence. Pay close attention to the research clues in the question stem, noting which part of the passage will help you answer the question. Then consult your passage map to refresh your memory of the main idea in that part of the passage. Finally, return to the passage and research the text of interest.

Take a look at the following two question stems. What would you say is the biggest difference between them?

Both are Inference questions. Both ask you to determine what the author of the passage would be likely to agree with. But where the questions differ is in your ability to research a specific part of the passage. In the first question stem, there are no clues pointing you to a specific portion of the passage. Instead, you’ll have to consult your big-picture summary (topic, scope, purpose) and evaluate each answer choice, checking it against the passage.

For the second question stem, though, notice the numerous clues it provides. It asks you to determine the author’s opinion of something explicitly stated in the passage—the nocturnal habits of newly discovered species in the Himalayan range. Untrained test takers might look at such a question stem and assume that their task is to answer the question based on their memory of the passage. But that’s often a losing strategy. Your memory of the details of the passage will likely be fuzzy, plus wrong answers will often present subtle distortions of ideas in the text, even using words and phrases from the passage. Instead, check your passage map for key information you may have noted about these animals and to confirm where in the text the author discusses them. Then go to the passage itself and reread just the section with the author’s comments on the nocturnal habits of these animals.

Researching the passage to determine the correct answer to a question is a skill that you can develop, just like every other step of the Kaplan Method. Each question type requires a slightly different research strategy.

Reasoning questions come in a variety of forms. A question might ask you to simply find an assumption of an argument, while another might ask you to identify a reasoning flaw. Some Reasoning questions will have you strengthen or weaken an argument, while others test your ability to resolve a paradox. See the section “How to Approach Reasoning Questions” toward the end of this chapter for examples of different types of Reasoning questions and predictable patterns to look for.

STEP 4

STEP 4Making predictions is one of the hallmarks of expert GRE readers. Unprepared test takers fall into the testmaker’s trap of using the answer choices to guide their thinking, but the testmaker does not write answers to help you clarify your thinking. If you approach the answer choices in this way, you may find yourself attempting to justify each choice as correct, and more than one answer choice will often appear reasonable.

Instead, use the information in the passage to arrive at a correct answer. After you have read the passage, identified the type of question you’re dealing with, and researched as appropriate, take a few seconds to imagine what the correct answer should look like. This is your prediction. Then, when you begin to read the answers, you will be able to rule out those that do not match your prediction—that do not match information in the passage—even if they seem like reasonable or relevant statements. It is, after all, much easier to find the answer choice you are looking for if you already have an idea what it looks like.

Of course, it is unusual that an answer choice will exactly match your prediction, word for word. Often, for example, your prediction will be general and the correct answer will be a specific instantiation of your general idea. However, the concept in the correct answer will match, and this is what’s important, not the exact language that is used. Note that if you mentally paraphrase the passage as you read, casting it into your own words, you will be prepared to recognize ideas in and inferences based on the passage when they are expressed in different terms.

Some question types, like open-ended Inference questions, might not lend themselves to a precise prediction. Other question types, like Detail questions, will nearly always lend themselves to a strong prediction. In your practice, you’ll start to figure out which question types take general and more specific predictions.

It might help to think of GRE Reading Comprehension questions as short-answer instead of multiple-choice. If you imagine that the questions require you to write a short-answer response, you will formulate a short sentence as an answer—and this is your prediction! You will then use that prediction as you evaluate the choices, eliminating those that don’t match and homing in on the choice or choices (for all-that-apply questions) that do.

If this step seems daunting, or if you find that no matter how hard you try to pause and predict an answer before evaluating the choices, you always rush through to the answers, try this exercise. Get some sticky notes and, during your next practice set of Reading Comprehension questions, cover up the answer choices with a sticky note. In your notebook, jot down what you think would be an appropriate response to the question.

With a strong prediction, you’ll be much less likely to be tempted by wrong answer choices. Indeed, if you see an answer choice that matches your prediction, confidently select it and move on to the next question.

STEP 5

STEP 5The first four steps of the Kaplan Method are all preparation for the final step: correctly answering the question. This step can be frustrating. How often have you found yourself in this position: you’ve read the passage and understand it; you’ve read the question stem and know your task; you’ve researched the passage and have an idea what the right answer choice looks like; but when you get to the answers, you find that two choices appear acceptable?

The testmaker is adept at writing deceptively appealing incorrect answer choices: that is, wrong answers that appear at first glance to be just as good as the correct answer. To recognize wrong answer choices on the GRE, it is valuable to know the ways in which the testmaker consistently creates wrong answers. In fact, just as there are predictable types of questions that the GRE recycles over and over again, there are also predictable and repeatable types of wrong answers.

Certain types of wrong answers will appear more frequently in certain types of questions and less frequently in others. For example, Outside the Scope and Extreme answer choices tend to show up in Inference questions, while Distortion answer choices are common in Detail and Function questions.

As you practice, pause and reflect not only on why right answers are right but also on what makes wrong answers wrong. Having a strong grasp what kinds of flawed answer choices to expect is nearly as powerful as researching accurately and making strong predictions. In time, you’ll be able to quickly and effectively eliminate incorrect choices and zero in on the correct one.

By practicing the five steps of the Kaplan Method, you’ll build your ability to attack Reading Comprehension passages with a consistent, methodical approach and reliably answer questions correctly. Now that you know what each step of the method entails, and why each step is so beneficial to your GRE score, let’s take an even deeper look at each step using examples.

STEP 1

STEP 1Apply your strategic reading skills to the passage below. Focus on how the author’s use of emphasis and contrast keywords telegraphs not just the author’s intent but also the passage’s overall structure. For each sentence, focus less on what is being said and more on why the author has included it. Is it simply background information? Is it the author’s main idea? Is it someone else’s opinion or belief? By asking and answering these questions as you read, you will be well prepared for the questions the test asks. Also, instead of trying to hold key ideas in your head, jot them down on scratch paper—make a passage map.

Many baseball enthusiasts are aware of the story of how Abner Doubleday invented the game of baseball with some friends in 1839 and introduced it to a nation during the Civil War. However, most baseball historians now agree that this story is a convenient fiction, propagated by Albert Spalding, a player, manager, owner, and one of the first manufacturers of sporting equipment. Spalding’s desire to distinguish baseball, which so keenly mirrored American interests and pursuits, from similar games played in England, such as cricket and rounders, led Spalding to seek out a purely North American origin of the sport. Spalding’s entire basis for the foundation of baseball history lay in a handwritten letter from 1907 that he said came from a man who claimed to have gone to school with Doubleday and attributed the invention to him. Despite the speculative and dubious claims of the letter, Spalding and other members of his commission were quick to adopt the narrative as gospel and began to market their sport to the masses as a truly American pursuit.

Below, check out how a GRE expert thinks as she reads the passage strategically, differentiating important information from background information.

Notice what a proficient GRE reader does. As she reads strategically, she “sums up” each sentence by mentally putting it into her own words. By paraphrasing, she separates key insights from nonessential background information. By the end, she understands the gist of the passage and has an excellent understanding of the passage’s topic, scope, and purpose. Here is this reader’s passage map.

Your passage map probably doesn’t use exactly the same words—everyone will map a passage a little differently—but your map should have captured the same ideas. Now apply Steps 2–5 to answer some questions about this passage.

Which of the following statements is suggested by the passage?

STEP 2

STEP 2The key phrase is “suggested by,” which indicates this is an Inference question. The correct answer is not explicitly stated in the text but can be discerned by an accurate reading of the text.

STEP 3

STEP 3This Inference question does not point to a particular statement in the passage, so you cannot research a particular sentence or section of the passage before approaching the answer choices. However, you can review your passage map so you have a firm grasp of the big picture of the passage; answer choices that contradict this or lie outside the scope of the passage can be eliminated. If any choices remain, you’ll need to check each one against the information provided in the text until you find one that is fully supported.

STEP 4

STEP 4Because of the open-ended nature of the question, you cannot formulate a precise prediction. However, your review of the passage map shows that because Spalding wanted to market baseball to Americans, he spread the story about an American, Doubleday, inventing it, even though Spalding had little evidence of this. Look for an answer choice that aligns with this main thrust of the passage, and look to eliminate choices that do not align.

STEP 5

STEP 5Eliminate choice (A) because it contradicts the main thrust of the passage, which is that “most baseball historians,” and the author, agree that Doubleday did not invent baseball. This was just a story that Spalding made up. Choice (B) might require some research. Spalding did make sporting equipment, and he was an avid promoter of baseball. However, he had a number of connections to baseball, and nowhere is it implied that he wanted to expand the fan base for the sport to increase sales of equipment. Choice (C) is Outside the Scope; the passage says that evidence for Doubleday’s inventing baseball is very weak, but it never discusses who did invent the sport. Choice (E) can be researched in the last sentence, which mentions that “other members of [Spalding’s] commission” promoted the story about Doubleday. However, the passage never says whether they believed the story or were skeptical of it. The correct answer is choice (D), which is supported by evidence in the passage. Spalding and his commission were eager to spread a story about an American inventor because they knew it would help market the sport to Americans.

Now try an all-that-apply question on the same passage.

Consider each of the choices separately and select all that apply.

Which of the following statements is true based on the passage?

STEP 2

STEP 2The phrase is “based on the passage” means this is an Inference question. As with all GRE Inference questions, while the correct answer(s) won’t be directly stated in the passage, it or they must be true given what is stated in the passage.

STEP 3

STEP 3This is another open-ended Inference question. Again, use your passage map to refresh your memory of the key ideas of the passage—any choice that contradicts these or is a 180°, wanders Outside of Scope, or is too Extreme can be eliminated immediately. Be prepared to research any remaining choices in the appropriate place in the text.

STEP 4

STEP 4While a precise prediction is not possible, having read the passage strategically and already answered one open-ended Inference question about it, you have a strong sense of what kinds of statements would and would not be supported by the text.

STEP 5

STEP 5Choice (A) is Outside of Scope of the passage, which only concerns whether Doubleday invented baseball; it does not discuss whether he existed at all. Choice (B) can reasonably be inferred. According to the second sentence, Spalding was a baseball player, manager, and owner, and according to the last sentence, he was a member of a commission that promoted the sport. In addition, he is believed responsible for perpetuating a widely believed myth about the origins of baseball. Thus, he was certainly influential in the game, and (B) is correct. Choice (C) is supported by the third sentence, in the middle of the passage, which describes cricket as a game “similar” to baseball. The similarity of the games was a reason Spalding was so eager to differentiate baseball by inventing an American origin story.

Now try a select-in-passage question. There is no need to approach this type of question any differently. Indeed, you can think of it as a multiple-choice question. There are five sentences in this passage, so they are your five answer choices.

Select the sentence in the passage in which the author states that there was only one piece of evidence supporting the view that baseball originated with Abner Doubleday.

STEP 2

STEP 2A key to choosing the correct answer to select-in-passage questions is to read the question very carefully. A rushed reading might focus on words like “Abner Doubleday” and “baseball,” and the test taker might think, “The whole passage is about that. How do I figure out which sentence to pick?” The words pointing you to the one and only sentence that fits the bill are “there was only one piece of evidence” for the Doubleday story. Only one sentence discusses the evidence for this origin myth.

STEP 3

STEP 3From your passage map, you know that the evidence was a letter.

STEP 4

STEP 4You will look for the sentence that mentions the letter and says it was the only basis for the story.

STEP 5

STEP 5You might recall that the passage begins by presenting background information and introducing the topic, that the story about Doubleday was largely the creation of Spalding. Only later does the passage discuss how Spalding came up with the story. So begin your scan for the correct sentence at the end of the passage. You’ll quickly find the fourth sentence: Spalding’s entire basis for the foundation of baseball history lay in a handwritten letter from 1907 that he said came from a man who claimed to have gone to school with Doubleday and attributed the invention to him. That fits the criteria of the question perfectly.

Some test takers feel less comfortable with passages about certain topics. Readers with a strong background in science may feel nervous about humanities passages, and readers well versed in the social sciences may approach physical science passages with some anxiety. However, the Kaplan Method and your strategic reading skills work equally well for all passages, no matter what your personal familiarity with the subject matter.

The last passage concerned history. Now try a passage with science content.

STEP 1

STEP 1Practice each step of the Kaplan Method with this passage and its associated questions. Read this passage strategically, using keywords, mentally paraphrasing, and making a passage map. Then use your knowledge of the Reading Comprehension question types to analyze the question stem, research the necessary information, form a prediction, and evaluate the choices.

Many tea drinkers believe that different teas—black, green, oolong, and so forth—come from different plants. In fact, however, all tea leaves come from Camellia sinensis, a large evergreen shrub. Native to China, the plant is now cultivated throughout Asia and in Africa, Europe, and North and South America. The character of various teas depends in some measure on the climate and soil where the plant is grown but mostly on how the leaf is processed after it is harvested. An interesting case is black pu-erh tea, a specialty of China’s Yunnan province. Unlike green or oolong tea, black pu-erh tea undergoes an oxidation process with the help of naturally occurring enzymes or, in the world of tea, is said to be “fermented.” It then undergoes an additional step that differentiates it from other black teas: after oxidation, the leaves are aged in humid conditions, sometimes for several decades. Like all other teas, pu-erh contains antioxidants, which may help protect regular consumers from some cancers. It also contains caffeine, though not as much as most other black teas. What really sets it apart from all other teas is the fact that it naturally contains small quantities of lovastatin, a medication that physicians prescribe to lower cholesterol. It is possible that certain fungi that colonize the tea leaves produce lovastatin as a metabolic by-product. Most pu-erh connoisseurs, while appreciative of the tea’s potential health benefits, are more intrigued by its taste, which they describe with words such as woody, earthy, and leathery. Clearly, an adventurous palate is necessary to enjoy this unusual beverage. Fortunately, those seeking a more conventional tea flavor have many options.

How did that go? Did you notice emphasis keywords that pointed to the author’s opinion or significant details? Did you identify contrast keywords indicating a change in direction or an unexpected discovery? Were you able to capture the passage’s topic, scope, and purpose and the main ideas in your passage map?

Here is a visual representation of how a GRE expert reads. This reader has trained himself to focus on key words and phrases, and these seem to leap out of the passage at him as though in bold print. These highlight the structure of the passage and point to the main ideas. He reads the less important details with less attention.

Many tea drinkers believe that different teas—black, green, oolong, and so forth—come from different plants. In fact, however, all tea leaves come from Camellia sinensis, a large evergreen shrub. Native to China, the plant is now cultivated throughout Asia and in Africa, Europe, and North and South America. The character of various teas depends in some measure on the climate and soil where the plant is grown but mostly on how the leaf is processed after it is harvested. An interesting case is black pu-erh tea, a specialty of China’s Yunnan province. Unlike green or oolong tea, black pu-erh tea undergoes an oxidation process with the help of naturally occurring enzymes or, in the world of tea, is said to be “fermented.” It then undergoes an additional step that differentiates it from other black teas: after oxidation, the leaves are aged in humid conditions, sometimes for several decades. Like all other teas, pu-erh contains antioxidants, which may help protect regular consumers from some cancers. It also contains caffeine, though not as much as most other black teas. What really sets it apart from all other teas is the fact that it naturally contains small quantities of lovastatin, a medication that physicians prescribe to lower cholesterol. It is possible that certain fungi that colonize the tea leaves produce lovastatin as a metabolic by-product. Most pu-erh connoisseurs, while appreciative of the tea’s potential health benefits, are more intrigued by its taste, which they describe with words such as woody, earthy, and leathery. Clearly, an adventurous palate is necessary to enjoy this unusual beverage. Fortunately, those seeking a more conventional tea flavor have many options.

Take a look at the following passage map and see how yours compares. Again, there are many “right” ways to map a passage—just make sure you noted the important ideas.

Now that you have read the passage strategically and made your map, try answering this question.

Consider each of the choices separately and select all that apply.

The passage suggests that which of the following would be a correct statement about tea subjected to an aging process?

Step 2—What kind of question is this?

Step 3—Where do you research?

Step 4—What is your prediction?

Step 5—What is your answer?

STEP 2

STEP 2The keyword “suggests” means this is an Inference question. This question asks about a specific idea in the passage, “tea subjected to an aging process.” The correct answer(s) must be true given the information that is provided in the passage.

STEP 3

STEP 3The “tea subjected to an aging process” discussed in the passage is black pu-erh tea. According to the passage map, black pu-erh tea is different from other teas in two ways: it contains lovastatin, and it has an unusual flavor. If these details are not captured in your passage map, you can find them in the latter half of the passage, where black pu-erh tea is compared and contrasted with other teas.

STEP 4

STEP 4You can infer that the ways in which pu-erh tea differs from other teas are due to the aging process it undergoes. The correct answer(s) will concern the cholesterol-lowering agent lovastatin and/or the tea’s distinctive taste.

STEP 5

STEP 5Answer choices (B) and (C) match this prediction. Choice (A) is Half-Right, Half-Wrong: the passage states that pu-erh contains “not as much” caffeine as other black teas, so the aging process can be inferred to remove some caffeine. However, the passage says that pu-erh tea (and all teas) contains antioxidants and does not indicate that the tea has fewer antioxidants than do other teas.

Now try another question about this passage.

Based on the passage, which of the following can be inferred about black teas?

Step 2—What kind of question is this?

Step 3—Where do you research?

Step 4—What is your prediction?

Step 5—What is your answer?

STEP 2

STEP 2The word “inferred” leaves little doubt this is an Inference question. Again, this question is directed at specific information in the passage—this time what the passage says about black teas.

STEP 3

STEP 3Review what the passage says about black teas. In discussing the processing steps that differentiate types of tea, the passage says that pu-erh tea is oxidized but that what makes it different from black tea is that it is also aged. Therefore, black teas are also oxidized, but they are not aged. The passage also says that most black teas contain more caffeine than black pu-erh. Moreover, the passage says that pu-erh is like “all other teas” in containing antioxidants, so black teas must contain antioxidants.

STEP 4

STEP 4The correct answer will correspond to one or more of the ideas in Step 3.

STEP 5

STEP 5Choice (D) says black teas are oxidized but not aged and is correct. Choices (A) and (B) both use comparisons between black teas and other teas that the passage does not support. Although the author says it is necessary to have an “adventurous palate” to enjoy pu-erh tea, this does not mean that people with adventurous tastes will prefer pu-erh tea to others; perhaps they will enjoy all kinds of tea equally. Therefore, choice (C) is incorrect. Because all teas contain antioxidants, which may protect against cancer, (E) is incorrect.

Now apply your Reading Comprehension skills to a longer passage, this one with a topic in the social sciences. Again, remember that neither the length of the passage nor the subject matter changes your approach. Use the Kaplan Method and your strategic reading skills to identify the important information and answer GRE questions.

STEP 1

STEP 1Questions 6 to 9 are based on this passage.

As the business world becomes ever more globalized and dynamic, freelance knowledge workers have come into their own. Technology drives rapid change in products and markets, and to keep up, companies find value in an on-demand workforce, one that they can adjust at will as new skills are needed. At the same time, the Internet means that a worker across the country or on the other side of the world can be as connected to a project’s workflow as someone seated in the company’s headquarters. Reflecting this reality, the U.S. Census Bureau’s count of “nonemployer businesses” rose 29 percent from 2002 to 2012, and according to one study, 53 million Americans—more than one-third of the workforce—engage in freelance work. The growth of so-called contingent labor is forecast to continue unabated. Clearly, not all labor is equally empowered in the new paradigm. The barista placing the artistically styled froth on a customer’s latte must be in the coffee shop. However, the systems analyst upgrading the shop’s financial system that tracks the sales of lattes can be anywhere. Thus, workers with intellectual capital are in prime position to choose where they work and for whom.

The transition to a labor market of independent professionals has social and cultural implications. In much of the world, work is a major source of identity, so when work changes, identity changes. Instead of identifying as Widgets Incorporated employees who, whether they are an executive or a janitor, will someday earn a gold watch with the Widgets logo engraved on the back, workers identify as designers or social media gurus or software engineers. Rather than forging a common bond with coworkers in a mix of jobs around the proverbial water cooler, freelancers build geographically dispersed networks with other self-employed professionals with similar skill sets. Furthermore, in the twenty-first century the workplace has become a primary site of social connections and thus an important thread in the fabric of social cohesion, but instead of going to an office for a large portion of the day where they assume their workday persona, the new entrepreneurs work at home—even in bed, where they tap out messages to clients on their smartphone while wearing pajamas. And instead of relying on company benefits packages when working or government-administered unemployment payments when not working, these workers attempt to provide for themselves in defiance of the vicissitudes of life. Not partaking in any communal safety net, they argue that in an era when layoffs are commonplace, being self-employed is little more precarious than working for an employer. The cumulative result of these changes may be, on the one hand, an integration of personal and work life not seen since the Industrial Revolution moved people from farms into factories and, on the other hand, the atomization of society as individual contributors of labor rent themselves out impermanently to companies around the globe without meeting their coworkers face-to-face. Contributing further to social disruption is the bifurcation of the labor market into the independent self-employed and those still dependent on traditional jobs. It remains to be seen whether this new generation of professionals will appreciate the degree of vulnerability that accompanies their freedom and reach out to find common cause with employees who still draw a steady paycheck, working together to address issues of security and dignity in the workplace.

STEP 2–5

STEP 2–5

The author is primarily concerned with

Step 2—What kind of question is this?

Step 3—Where do you research?

Step 4—What is your prediction?

Step 5—What is your answer?

Select the sentence that best summarizes the author’s conclusion about the historic impact of the growth of the independent workforce.

Step 2—What kind of question is this?

Step 3—Where do you research?

Step 4—What is your prediction?

Step 5—What is your answer?

Consider the choices and select all that apply. Based on the passage, one can infer that the author would likely agree with all of the following statements about self-employed freelancers EXCEPT

Step 2—What kind of question is this?

Step 3—Where do you research?

Step 4—What is your prediction?

Step 5—What is your answer?

The author mentions “government-administered unemployment payments” in paragraph 2 in order to

Step 2—What kind of question is this?

Step 3—Where do you research?

Step 4—What is your prediction?

Step 5—What is your answer?