2.1 Goals

Strategy is the art and science of developing and deploying all of a company’s resources so as to achieve the most profitable long-term survival of the company. Strategy is all-encompassing and affects all functions. A company’s strategy must embody a high-level vision for the firm, but it must also be concrete and practical. Developing strategy starts with the company’s goals, from which specific objectives for managing each aspect of its business, including price, can be derived. Having clear, unequivocal goals and targets is an indispensable prerequisite for professional price management. While this may sound simple, developing such clear strategic goals can be difficult in practice. Objectives for price policies are not always clearly formulated and may occasionally give greater weight to unspoken goals than to explicit ones.

Profitability goals (profit, return on sales, return on investment, shareholder value): Most companies pursue profitability goals in a more or less well-defined form. While short-term profitability goals often differ, ultimately, the most important long-term goal is to increase shareholder value.

Volume and growth goals (volume, market share, revenue, or revenue growth): Volume and growth goals are alternative goals or proxies for long-term profit maximization or growth in shareholder value. Since its founding in 1994, Amazon has focused almost exclusively on growth and, as a result, has not made any significant profit in its first two decades. In 2015, the company achieved an after-tax profit of $596 million on revenue of $107 billion, which corresponds to a margin of 0.56%. In 2016 Amazon’s revenue increased to $136 billion and its after-tax profit to $2.37 billion, corresponding to a margin of 1.7%. By the beginning of 2018, Amazon’s market capitalization had almost doubled in 3 years to $669 billion, an immense increase in shareholder value.

Financial goals (liquidity, creditworthiness, debt-to-equity ratio): These goals come to the fore in particular for new companies short on capital or for any company facing a crisis.

Power goals (market leadership, market dominance, social or political influence): Volkswagen sets itself a singular goal: outsell Toyota. It is often said that Google wants to dominate the markets it enters. Peter Thiel’s bestseller “Zero to One” encourages companies to find niches they can monopolize. Fighting and beating the competition is a very common goal of managers.

Social goals (creating/preserving jobs, employee satisfaction, fulfilling a grander social purpose): In line with such goals, a company will sometimes accept orders at prices which do not cover costs, in order to avoid cutting jobs. Companies may also cross-subsidize products or services in order to make them accessible to target segments who otherwise might not be able to afford them—for instance, providing student or senior citizen discounts. For Patagonia, the maker of outdoor and athletic gear, environmental sustainability is a core part of the mission. Patagonia donates employee time, services, and at least 1% of sales to grassroots environmental groups all over the world in service of its social goal.

Almost all goals have an effect on price management, though price is certainly not the only instrument companies use to achieve their goals. In the pursuit of growth goals, a company might rely on innovation, or it could set aggressive low prices. Companies can meet profit and financial goals through cost-cutting, or they could raise their prices. To fulfill their power goals, companies might wage a price war or take control of a distribution channel. In most cases, price makes an important contribution to achieving a company’s strategic goals.

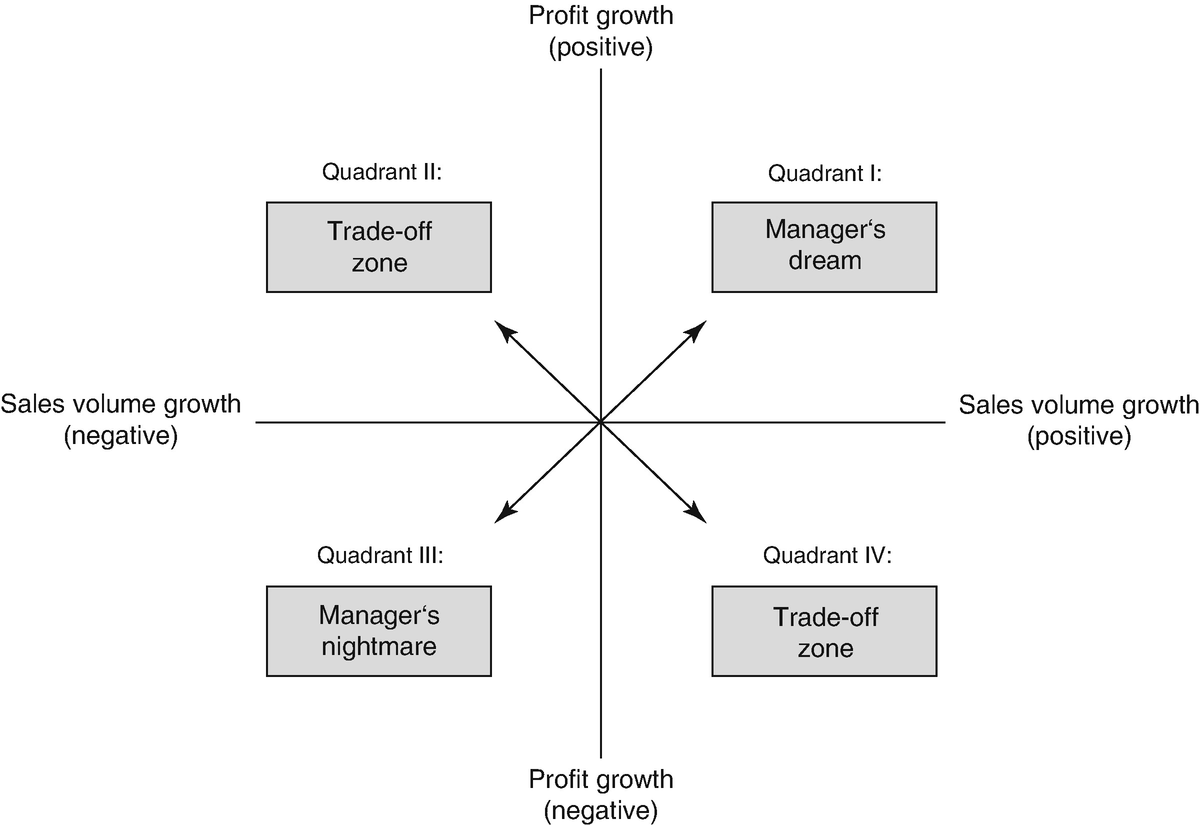

Goal conflict: Profit growth, volume growth, or both?

Quadrant I shows the “manager’s dream”—profit and volume are both growing simultaneously, a situation most frequently encountered in expanding markets or with new products just achieving economies of scale. For a mature market that is no longer growing, the manager’s dream can only occur when a company’s prices are too high and are cut as a result. In that case, the lower prices lead to a significant increase in volume, overcompensating for the lower margin, and generating a higher profit.

In practice, we observe the situations in quadrants II and IV quite often. A company achieves either profit or volume growth, but not both. Quadrant II represents rising profit and declining volumes. In this case, the company’s prevailing prices were below the optimal level. Increasing the prices leads to a volume decline, but the higher contribution margin more than offsets that decline and results in a higher profit. In Quadrant IV the profit decreases, but the volume grows. This situation occurs when a company’s prices were either at or below their optimum and then get cut. In Quadrant II as well as in Quadrant IV, management must choose between the countervailing profit and volume changes. No matter what, managers should avoid Quadrant III, which we refer to as the “manager’s nightmare.” If prices are already too high and are then increased even more, the result may be a decline in both profit and volume.

Contradictory goals among senior leaders

Senior leader | Profit | Growth | Market share |

|---|---|---|---|

Chief executive officer | 1 | 3 | 2 |

Chief financial officer | 2 | 1 | 3 |

Head of sales | 1 | 2 | 3 |

Head of marketing | 2 | 3 | 1 |

Product manager | 3 | 1 | 2 |

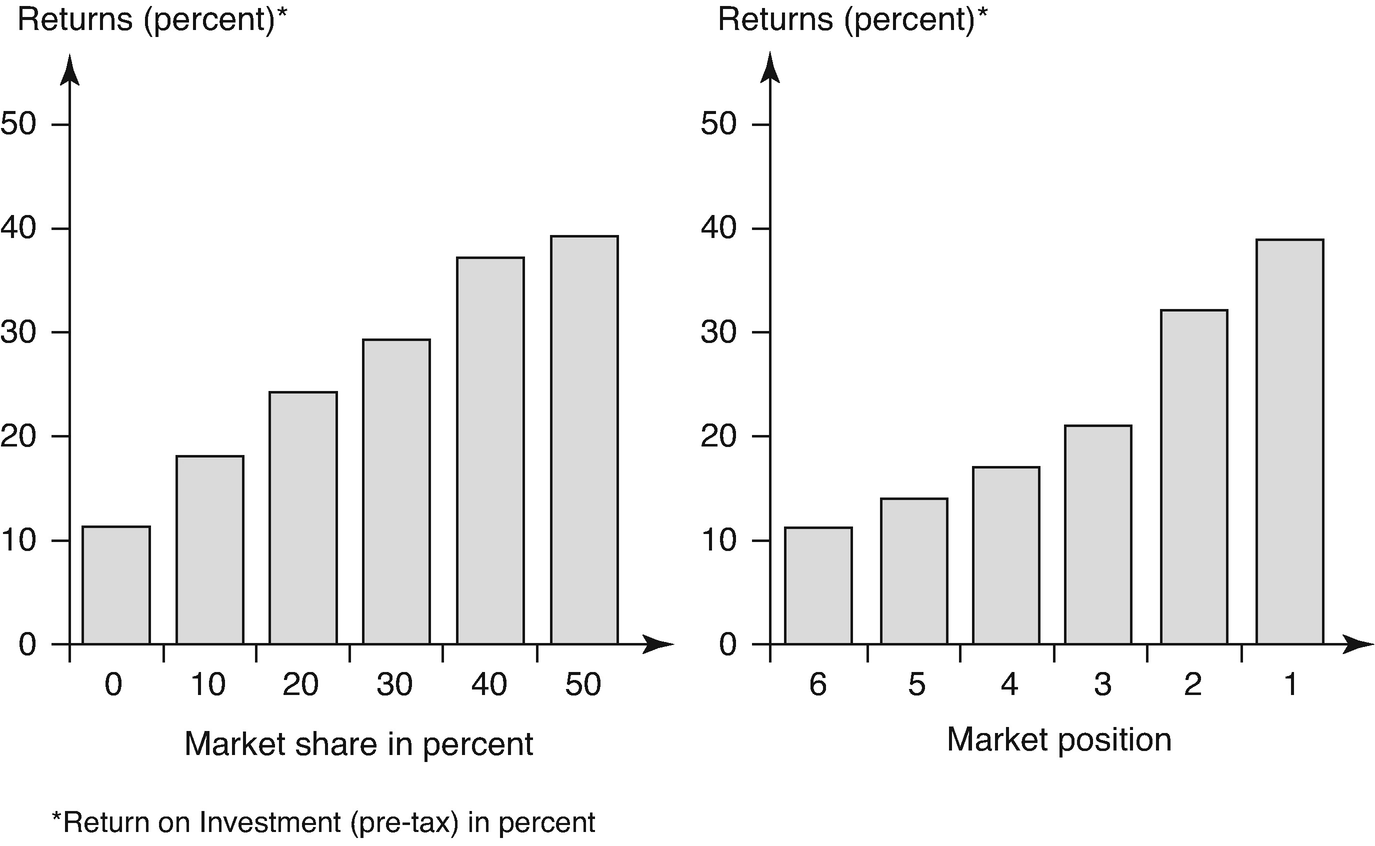

Results of the PIMS study [1]

A second and somewhat older justification for the pursuit of high market shares is the concept of the experience curve, which states that the cost position of a company is a function of its relative market share. The relative market share is defined as one’s own market share divided by the market share of the strongest competitor. According to the experience curve hypothesis, the larger a company’s relative market share is, the lower its unit cost will be [2]. The market leader has the lowest costs in the market and thus—assuming the same prices across competitors—the highest returns.

The experience curve concept and the PIMS study are the grandparents of all market share philosophies. Jack Welch, CEO of General Electric from 1981 to 2001, became their most famous proponent. At the beginning of his tenure, he declared that General Electric would withdraw from all sectors in which it could not attain the number one or number two position in terms of market share.

The central question is whether the link between market share and returns reveals a true causal relationship or merely represents a correlation. Numerous studies have called into question whether a causal relationship actually exists. The results in fact show a much weaker link between market shares and returns than what the authors of the PIMS study postulated. Farris and Moore [3] provide an overview of the insights. Analytical methods which filter out so-called “unobservable” factors lead to the following conclusion: “Once the impact of unobserved factors is econometrically removed, the remaining effect of market share on profitability is quite small.” These “unobserved” factors include the capabilities of a company’s management, the corporate culture, or a sustained competitive advantage. Ailawadi et al. [4, p. 31] conclude: “Although high market share, by itself, does not increase profitability, it does enable high-share firms to take certain profitable actions that may not be feasible for low-share firms.” A study by Lee [5] likewise comes to the conclusion that not more than 50% of a company’s profitability can be explained by absolute size and that other factors play the decisive role for return on investment. “While a typical firm’s absolute size matters for its profit experience, perhaps some other factors matter even more” [5, p. 200].

The most comprehensive meta-analysis on this topic to date comes from Edeling and Himme [6]. They examined 635 empirically calculated elasticities for market share and profit which reflect the percentage change in profit when market share increases by 1%. Here we note that these calculations measure changes in the starting values in percent and not percentage points. The authors found that the average elasticity for market share and profit is very low, at 0.159, but statistically significant. The following example demonstrates the findings of their study. Let us assume a company has a market share of 50% and a profit margin of 10%. If the market share rises by 1–50.5%, the profit margin rises only to 10.0159%. If the market share rises by 10–55%, the profit margin would increase to 10.159%. In a further step, Edeling and Himme [6] eliminated the skewing induced by his analytical methods and arrived at a slightly negative adjusted average market-share-profit elasticity of −0.052, which was not statistically significant. These results more than call into question the validity of the “market share is everything” philosophy.

Older studies considered the effects of competition-oriented corporate goals (such as market share or market position) more thoroughly. Lanzillotti [7] conducted a well-known study of this kind. It revealed a negative correlation between the pursuit of competition-oriented goals and a company’s return on investment. Armstrong and Green [8, p. 2] concluded that: “Competitor-oriented objectives are harmful. However, this evidence has had only a modest impact on academic research and it seems to be largely ignored by managers.” We find additional empirical evidence for a negative link between the pursuit of market share and the success of a company in a study from Rego et al. [9]. Using data from 200 US companies, the authors identified a trade-off between the pursuit of higher market share and higher customer satisfaction, which itself is seen as an important driver of long-term profitability [10]. The authors explain this through the heterogeneity of consumer preferences: the larger a company becomes, the harder it is for the company to meet consumer preferences. These are only a few studies among many which have explored the effects of market share goals, the experience curve, or portfolio management based on the “Boston Matrix.” For many other arguments against the “market share myth,” we refer the reader to the book “The Myth of Market Share” by Miniter [11]. In summary, the pursuit of volume and market share goals—especially in mature or highly competitive markets—is problematic and in many cases prevents a company from earning higher profits.

A company’s size can make it difficult to increase revenue. A growth goal of 50% for a company with $10 million in revenue means an increase of only $5 million. For a company with revenue of $150 million, the same goal would call for a revenue increase of $75 million. Once a company reaches a certain size, there may not be a sufficient number of customers or suppliers to enable further rapid growth.

Albert M. Baehny, the non-executive chairman and former CEO of Geberit, also disagrees with the supposed importance of market share: “I am not interested in market share. In my career, I hardly ever looked at market share. If the price-value relationship is good, the demand will follow” [12]. Geberit is the global market leader for so-called behind-the-wall sanitation products and has a market capitalization which is roughly five times its annual sales. Baehny emphasized that when his company decides whether to introduce a new product, it does not look at the product’s market potential or achievable market share. According to him, such forecasts are too unreliable. Instead, Geberit identifies the product’s value to the end users and uses that metric to ensure a sufficient willingness to pay for the product.

In our view, what matters is not the absolute level of the market share but how a company achieves its market share. If that market share comes through aggressive prices without a correspondingly low-cost base, then a company has “bought” that market share at the expense of its profit margins. This is true for many start-ups, which spend exorbitantly to acquire customers in the hope that they will one day be profitable at scale. However, it means per se that in most cases, the company will not earn much profit. If the company achieves its high market share through innovation and quality at appropriate prices, then margins and profits are healthy and aligned. The high profit in turn allows the company to make additional investments in innovation and product quality. Recent studies, such as one from Chu et al. [13], examine the link between market share and profitability in a homogeneous sector (insurance) and confirm this strategy: a company can improve its profitability by developing new services or technologies or by growing market share through acquisitions.

It is clear that balancing profit and volume goals is necessary for price management. In the early stages of a market or a life cycle, it can make sense to give greater weight to volume, revenue, or market share goals. In the latter phases of the product life cycle, a company should put higher priority on profit goals. Ultimately, management should orient itself toward long-term profitability.

2.2 Price Management and Shareholder Value

Profit and growth drive shareholder value. Because price exerts a strong and decisive influence on both profit and growth, price is a crucial determinant of shareholder value. More and more managers have begun to recognize this connection. They have incorporated it into their strategic planning as well as into their communication to the capital markets [14]. Investor Warren Buffet’s claim that pricing power is the most important criterion for determining the value of a firm has boosted this trend. Well-known Silicon Valley investor Peter Thiel likewise stresses the connection between price and shareholder value, as he is decidedly in favor of using pricing power to expand a market position [15].

As we will see, price management can dramatically impact shareholder value, both positively and negatively. Good price management fosters a significant increase in enterprise value. Mistakes in price management can destroy enterprise value. The following cases prove that the destructive effects take hold much more rapidly than positive (long-term) growth in enterprise value.

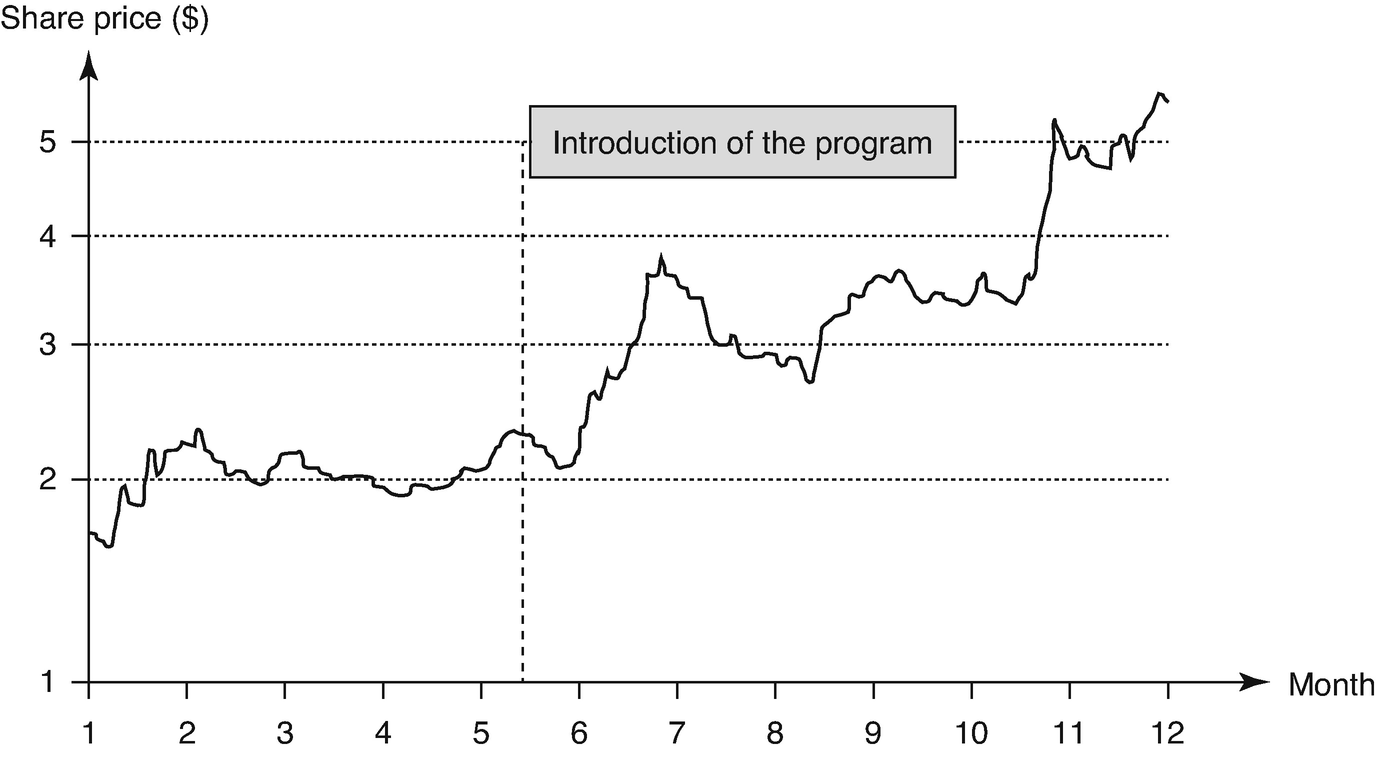

Price discipline and share price of a telecommunications company [16]

The company’s CEO greeted the stock market’s positive response by saying: “We are very satisfied with our disciplined approach to pricing. The results reflect a positive dynamic in our industry, which includes diminished price pressures.” Investment analysts also praised the newfound price discipline. “The rise in wholesale prices reflects the trend toward reduced price pressures, a very healthy development. More stable prices should help all market participants,” said one report.

Another case involves a group of private equity investors who owned a large operator of parking garages. The investors planned to use price management to increase the value of that operating company prior to divesting it. They succeeded in implementing price increases and built the new prices into the contracts with the local garage lessors, thereby locking in an additional profit of $10 million per year. Shortly after this price action, the investors sold that company at a multiple of 12 times profit. The price increases led directly to an increase of $120 million in enterprise value.

A third case looks at the market for luxury goods. The French company Hermès is known for its strict commitment to high prices and the avoidance of price erosion in any form. The Wall Street Journal writes that: “Hermès bets on higher prices while others even cut their prices” [17]. In contrast to other luxury goods companies, Hermès sticks to this strategy even in economic downturns and crises. While the JBEF Luxury Brands Index did not move from 2015 through March 2017, the share price of Hermès almost doubled in the same period. The company’s consistent price strategy made a decisive contribution to that increase.

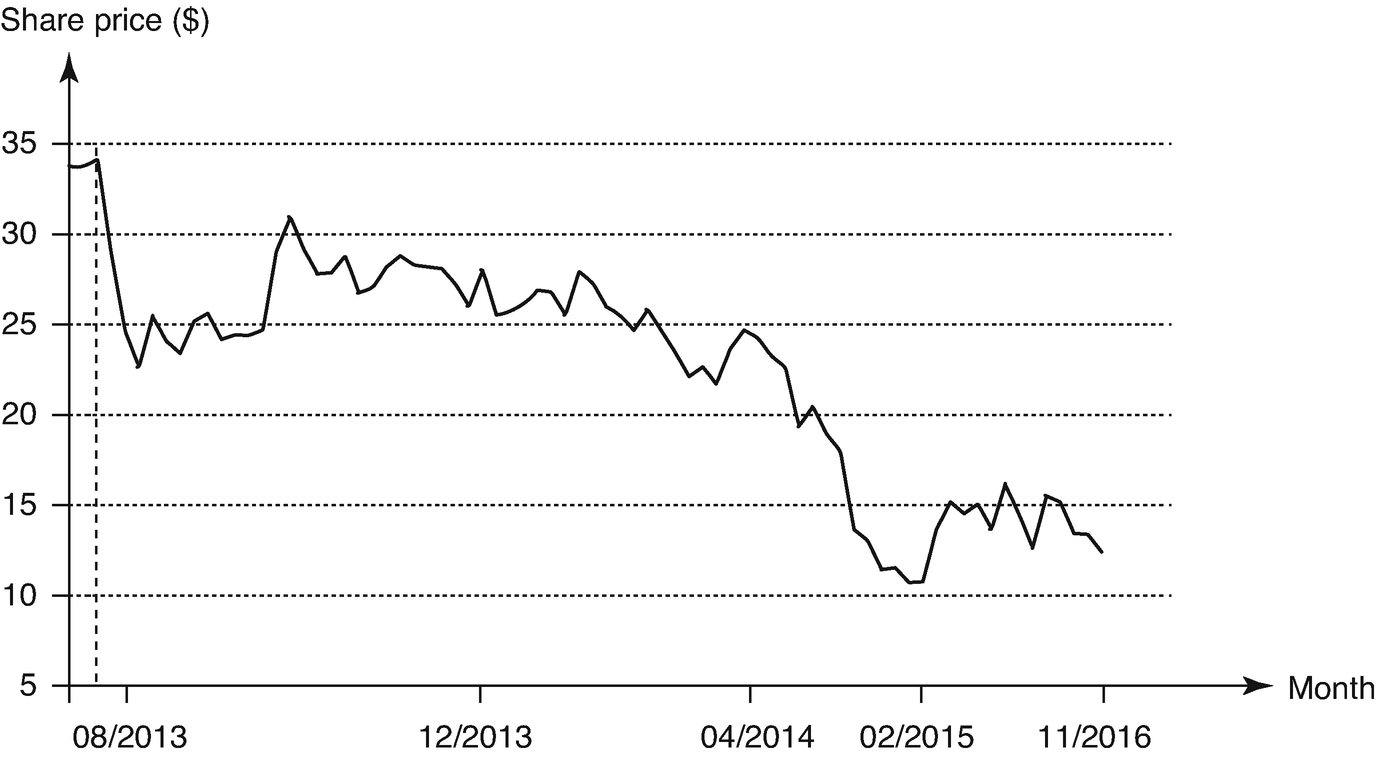

Share price of Praktiker [19]

What is interesting is that during that same time period, other home improvement chains flourished and were able to increase their revenues. The Praktiker case shows that a company should carefully consider the potential consequences of building a market positioning exclusively around low prices. This strategy and the subsequent attempt to overcome its consequences both ended badly for Praktiker. Praktiker went bankrupt in the fall of 2013 and no longer exists.

Share price of Uralkali [20]

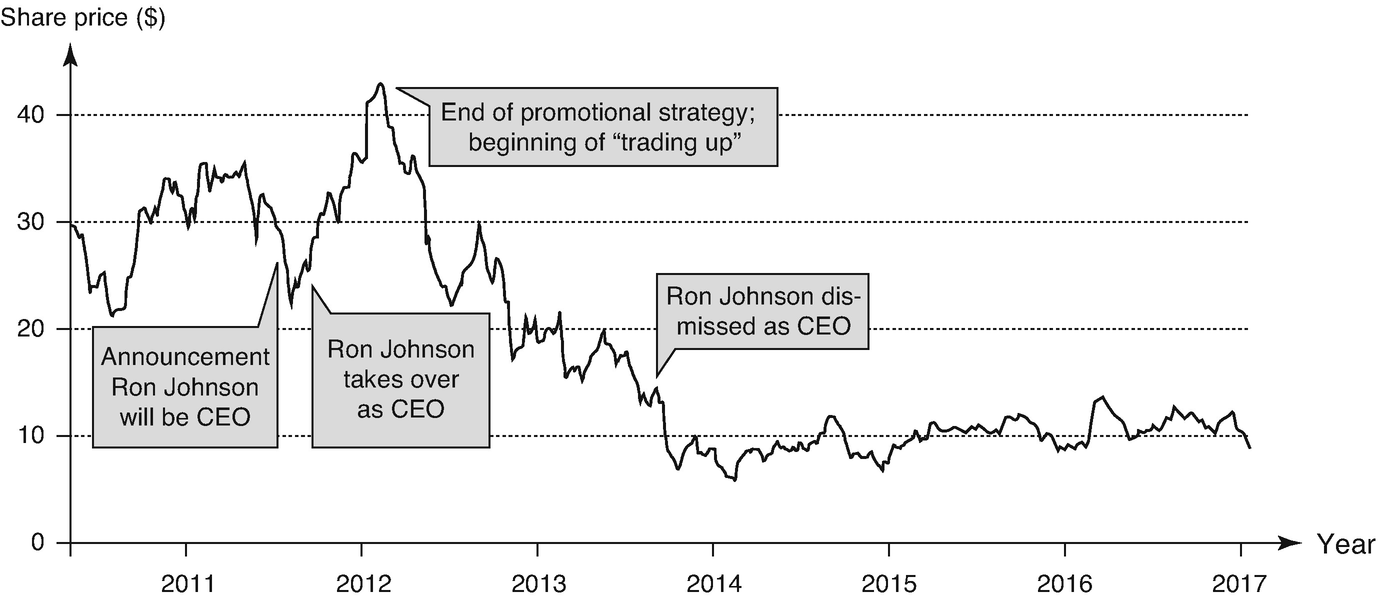

Share price of J.C. Penney [22]

Marketing science has historically conducted scant investigation into the relationship between marketing instruments and shareholder value. In recent years however, this has begun to change for the better. In a meta-analysis of 83 studies, Edeling and Fischer [10] found that advertising has a slight positive effect and that so-called marketing-asset variables (which include brand and strong customer relationships) have a significantly stronger effect on shareholder value. The median elasticity was 0.04 for advertising and 0.54 for the marketing-asset variables. In other words, a 1% improvement in marketing generates an increase of 0.54% in enterprise value. Price was not explicitly studied in the meta-analysis, so it is not possible to say anything about the price vs. shareholder value elasticity. Two additional studies looked at how price actions and innovation affect shareholder value. Pauwels et al. [23, p. 142] came to the following conclusion: “New product introductions increase firm value, but promotions do not.” The findings from the study conducted by Srinivasan et al. [14] point in the same direction. Innovations and marketing support for them drive higher enterprise value, but price actions (i.e., discounts or aggressive price moves) have a negative effect. Our own experience leads us to support these findings emphatically.

These elaborations and empirical insights prove the strategic relevance of price management for the value of an enterprise. With the help of the right price strategy, a company can increase the enterprise value. At the same time, the wrong price positioning can reduce shareholder value and can even—as the case of Praktiker shows—destroy it completely and forever.

2.3 Value and Price

The core questions of strategic price management concern value and price positioning. We are asked again and again what the most important aspect of price management is. We always give the same answer: “value-to-customer. ” The price a customer is willing to pay, and thus the price the seller can achieve, is always a reflection of the customer’s perceived value of the product or service. If customers place a higher value on the product, then they are prepared to pay more. If the perceived value is lower than that of a competing product, they will only buy the product if the price is also lower (relative to the competitive product). This unwavering market view was best expressed by Peter Drucker, who urged managers to “see the entire business through the eyes of the customer” [24, p. 85]. When it comes to the price that a seller can achieve, the most relevant parameter is the customer’s subjective perception of value.

Create value : Innovation, product quality, the standards and nature of a product’s materials and components, design, etc., all contribute to value creation. The choice of customer segments also influences value creation, because customers have different requirements and different perceptions.

Communicate value : Statements about the product, its position, and last but not least about its brand all communicate value. Value communication includes packaging, product presentation, and placement at shelf or online.

Retain value : The degree to which a product retains its value will influence first-time willingness to pay for consumer durables. For luxury goods and automobiles, value retention—resale value—can even constitute a deciding factor for initial willingness to pay.

Only when a seller has clarity on the value of the product or service can the seller approach the specifics of price setting. When establishing value—which in practice spans a very wide range from highest to lowest quality—the seller or supplier must be mindful of the achievable price from the very beginning. Ramanujam and Tacke [25] insist in their book “Monetizing Innovation” that companies should design a product around a price. In other words, they should start with the price range and then begin with research and development, designing a product with the appropriate features and quality for that price range. Putting effort into understanding value is likewise important for the buyer. The only way for buyers to avoid overpaying is to understand the value of what they are buying. This knowledge of value protects the potential customer from buying a product which looks like a bargain at first glance but upon use or consumption turns out to be a lemon [26]. The Spanish philosopher Baltasar Gracian (1601–1658) stated this sentiment eloquently and succinctly: “It is better to be cheated in the price than in the quality of goods” [27]. Ripping off a customer by charging too high a price is infuriating for the customer—but this anger is often only temporary. Selling a buyer goods of poor quality, however, causes the anger and frustration to linger until the customer grows tired of the product and disposes of it. The moral of this story is that when negotiating and making a purchase, the buyer should pay more attention to the quality of the product or service than to its price. Admittedly, that is not so simple in practice. It is generally easier to judge whether a price is advantageous than to judge the full merits of a product or service.

A French saying echoes this sentiment: “Le prix s’oublie, la qualité reste,” which essentially means that quality endures long after you have forgotten the price. It is not uncommon for prices to be ephemeral and quickly forgotten, while impressions of value and quality last much longer. Who has not hastily celebrated capturing a bargain or paying a low price, only to find out later that quality was poor and the bargain an illusion? Conversely, who has not at least once complained about paying a high price and then been pleasantly surprised when the quality turned out to be excellent? The English social reformer John Ruskin (1819–1900) described this insight succinctly: “It is unwise to pay too much, but it is worse to pay too little. When you pay too much, you lose a little money—that is all. When you pay too little, you sometimes lose everything because the thing you bought was incapable of doing the thing you bought it to do. The common law of business balance prohibits paying a little and getting a lot—it cannot be done. If you deal with the lowest bidder, it is well to add something for the risk you run, and if you do that you will have enough to pay for something better” [28]. Buyers who choose the lowest-priced suppliers may not be aware of or heeding Ruskin’s wisdom.

2.4 Positioning

Potential price positions

A product’s positioning should never be based solely on price but should rather reflect the underlying basis of the product’s or service’s value, including its brand. Positioning, in this sense, is synonymous with “price-value positioning” or “price-performance positioning.” A product’s positioning provides the fundamental orientation and leeway for price decisions. The positioning can apply to the entire firm, to a particular brand, to a product group, or even to an individual product.

Functional

Emotional

Symbolic

Ethical

Functional attributes apply to each performance element of the product or service with respect to its ability and suitability to satisfy the customer’s needs [30]. The functional attributes enable the customer to solve a specific core problem or mission, i.e., for an airline the problem of transporting passengers from point A to point B. Functional performance would also encompass the resources and infrastructure necessary to meet these transportation needs. For a smartphone, attributes such as screen size and battery life comprise the functional performance. For a laptop computer, functional attributes include the processor speed and the amount of memory.

Emotional attributes refer to the value that the customer derives from the product because of positive feelings the product elicits. Needs such as the desire for change or escape, excitement, sensory pleasure, sensual experiences, or beauty are fulfilled by emotional attributes [30]. For a car, this can mean the fun of driving a sports car or the pleasure from appreciating the car’s aesthetics and design. Customers feel pleasure or even excitement when they spend a night at a luxury hotel, and these count as emotional benefits. A product’s or service’s ability to stimulate emotions can have a pronounced effect on the willingness to pay.

Symbolic attributes refer to the value a customer gains from a boost in confidence or self-esteem from the product or service. These attributes allow customers to associate themselves with a group or person, express their belonging (actual or desired) to a particular group, or conversely, to separate or distinguish themselves from a group. They also fulfill the need for social recognition or serve as a form of self-expression [30]. Brands play a very important role as symbolic attributes. A very expensive watch, say from Rolex, or an exclusive suit from Zegna, confers social prestige and creates the impression that one belongs to a certain social class. This symbolic performance, in the sense that it signals membership in a certain group, is a powerful driver of willingness to pay. Similarly, driving a Porsche vs. driving a Toyota Prius sharply conveys different symbolic attributes.

Ethical attributes include those which foster the positive feeling that one has done something beneficial for others, for society, or for the environment. These attributes are the focus of mission-driven brands. This feeling likewise provides customer value, as the other three categories of performance attributes do. Through these attributes, one expresses and fulfills one’s desire to help others in a specific way or manifests the general desire to act morally or altruistically [30]. Examples of ethical performance include Procter & Gamble’s “One-Pack = One Vaccine” campaign, under which the company pledged to provide UNICEF with funding for one lifesaving tetanus vaccine to protect a mother and her newborn in the developing world for every package of Pampers diapers purchased in the United States or Canada. Other such examples are the drinking water initiative from the Volvic water brand and the Breast Cancer Awareness Campaign sponsored by Estée Lauder. These companies attract customers through a commitment to support charitable initiatives or serve a larger social cause. This commitment can influence the willingness to pay.

Overview

Each of these four types of performance attributes is capable of fulfilling customer needs and thus of generating willingness to pay. This means that the nature or extent of a product’s performance must always be incorporated in its positioning. All marketing instruments and other corporate activities such as R&D, procurement, and even the selection of personnel should be consistent with the price position for which the company is striving. A company needs a fundamentally different showroom and a different caliber of salesperson for luxury cars than it does for low-price models. In addition to this consistency, a company also needs endurance, because it can take years to establish the desired price position.

2.5 Approach

Price and value should always be seen relative to each other. As Fig. 2.7 shows, one must interpret the price position from the perspective of the price-performance or price-value relationship. The consistency band in Fig. 2.7 illustrates the ultra-low, low, medium, premium, and luxury price positions. The dimensions of price and performance are at different levels for each position, but in balance with each other. The perception of the customer is the factor which counts.

Deviations from the consistency band may be viewed as fair or unfair in the eyes of the customer. A fair or advantageous position (again, in the eyes of the customer) reflects a favorable price-performance relationship. The customer perceives a surplus of performance relative to price. The unfair position results when the seller demands a high price which is not aligned with the perceived value or performance. A Dutch customer’s comment on a German engineering firm illustrates this: “Your price is 1.2 million euros. The price from a Chinese supplier is 750,000 euros. I realize that your product is better, but it is not 60% better. So I will not pay 60% more.” The Dutch customer bought the Chinese equipment.

In 2016, Sprint began to use that same kind of quantification and logic to its advantage in its advertising campaigns. Under the slogan “Don’t let a 1% difference cost you twice as much,” Sprint presented data which show that its network reliability is within 1% of the performance of competitors such as AT&T and Verizon, but its plans are 50% less expensive. Some companies, meanwhile, are criticized that their price-performance relationship is out of whack, even in the absence of numbers for comparison. McDonald’s is one example, as one observer remarks. “Nowadays the Big Mac in America costs $4.80. The price-value relationship is completely off” [31].

To develop solid price positions for a product or service, we recommend a three-step approach. First, a company should make a rough segmentation of its market from a price-performance perspective. Start by delineating the market, including an analysis of customers and competitors. A valid market segmentation is an indispensable prerequisite for successful price positioning. Within the framework of the company’s strategic direction, the company then selects one or more target segments and the appropriate price position for each one. Related to this task, the company must also decide whether it will use one brand or multiple brands to cover the different price positions. When Apple launched its smart watch in 2015, the “Apple Watch” brand served several segments across an extreme price range from $349 all the way to $18,000 per watch [32]. Later the watches were available between $249 and $1399. Apple removed the “luxury” edition from the assortment.

In saturated markets or markets where market fragmentation is increasing, a rough segmentation is usually not sufficient. Within a chosen price range, one must further differentiate from the competition. A premium supplier can examine whether it has enough price leeway to extend into the luxury segment. In a similar way, at the lower end of the price scale, there may be additional demand at prices below the current price levels. No-frills airlines and hotels have greatly expanded the overall travel market with low-price positions.

In the low-price segment, the functional attributes tend to dominate. Customers in these segments are interested in basic products and services, such as economical transportation. Additional performance attributes such as a powerful engine, comfort, sportiness, aesthetic design, or prestige play a secondary role. In the premium segment, customers demand not only a higher level of performance on the functional attributes; they also give increasingly greater weight to emotional, symbolic, and ethical attributes. Buyers of electric cars put symbolic and ethical attributes at the forefront of their decision-making. Such customers will only develop the appropriate willingness to pay when these attributes fulfill or exceed their expectations.

Price positioning must be regarded as a strategic decision because of the inherent risks involved. Because price positioning is established for the long term, it is very difficult to correct mistakes. Despite this, improper positionings are not uncommon in practice. The so-called “Personal Transporter” Segway, a revolutionary innovation and cult product, was introduced in 2001 at a price of $4950. Nowadays, the least expensive model i2 SE costs $6694, which one can confidently declare to be a luxury positioning for that kind of vehicle. Sales projections called for 50,000 units in the first year and average annual sales of 40,000 units in the first 5 years. In reality, the company sold only 4800 units per year in the first 5 years after launch. They fell short of the original volume target by 88%. The primary cause for this shortfall was probably the product’s misaligned price positioning [33].

In 2014, Amazon introduced the “Fire” smartphone at a price of $200. This launch price reflected a medium-price positioning between basic Android phones and the more expensive iPhone. Yet no one bought the “Fire” at that price. Amazon responded by cutting the price to just $1, but even this radical move could not save the product. Amazon wrote off $170 million as a result. Apparently, Amazon was way off in its estimates of consumers’ willingness to pay [34].

Similarly, the luxury goods brand Gucci failed to assess its potential customers correctly when it assumed that a higher price would automatically make the brand even more luxurious and sought after. The attempt to raise handbag prices by then-CEO Patricio di Marco proved to be unsuccessful due to a miscalculation regarding customers and their preferences. The case shows that a price increase alone does not create or improve a luxury brand [35]. Successive price increases by the British leather goods maker Mulberry brought sales to a virtual standstill. Customers found one price increase of several hundred pounds particularly unjustified. The image of the brand simply did not live up to the prices the company was charging. Declining revenue and frustrated customers prove that a price repositioning cannot be effected over a brief period. The positioning must unfold as a long-term process both within the company and in the eyes of the customers [36].

We have also witnessed numerous cases in which a company chose a price position which was too low. Playmobil priced its new “Noah’s Ark” set at €69.90. The product soon sold on eBay for €84.09, a clear indication that the product’s price position was too low. In 2014, Microsoft launched the hybrid tablet Surface Pro 3, which could completely replace a laptop. The tablet sold out immediately. The primary reason was a price position which was too low relative to competitors such as Apple and Samsung. The British firm Newnet introduced an “uncapped service” for £21.95 per month, but the first 600 customers immediately used up all available capacity. As a result, the company raised the price by 60% to £34.95. The Taiwanese computer maker Asus launched the mini-notebook “Eee PC” at €299, and similar to Microsoft’s tablet, this product sold out within a few days. During the launch phase, the company could only satisfy 10% of the actual demand.

The Audi Q7 was also positioned too low, entering the market at €55,000. The company received 80,000 orders against an annual production capacity of only 70,000 units. Procter & Gamble overhauled the pricing for its Olay “Total Effect Creme,” raising the price by 375% from $3.99 to $18.99. The creme sold even better than before at the much higher price. Subsequent products received the same positioning in this higher price segment. Procter & Gamble succeeded in boosting the Olay brand from a low-price to a medium-price position [37]. These cases illustrate the enormous significance of finding the optimal price positioning when launching a new product.

2.6 Price Positions

In this section we will elaborate on the five basic options for price positioning. We will look at the following categories: luxury, premium, medium, low, and ultra-low. We start with the luxury segment.

2.6.1 Luxury Price Position

2.6.1.1 Basics

Examples of luxury and premium price positions, Status: February 2018

Product | Premium price position | Luxury price position |

|---|---|---|

Wristwatch | Michael Kors Ceramic MK5190, $348 | A. Lange & Söhne, Lange 1 Tourbillon Platinum, $403,000 |

Car | BMW 7 Series, base price $83,100 | Ferrari 458 Italia, base price $264,000 |

Hotel | Hilton New York Midtown, $269 | Burj Al Arab Dubai, Royal Suite, $13,058 |

Flight | Lufthansa Business Class, Frankfurt to Moscow $1031 | Lufthansa Private Jet, Frankfurt to Moscow, $20,794 |

T-shirt | Ralph Lauren, $79 | Prada, $740 |

Another distinction for luxury goods is their unit sales. Among true luxury goods, annual global unit sales often total only a few hundred, perhaps a few thousand, while premium products can generate volumes in the hundreds of thousands or even millions of units. Rolls-Royce sold only 4011 cars in 2016. Ferrari limited its sales volume in 2016 to 8014 units. In contrast, Porsche shipped 237,800 new vehicles in 2016. Although all three brands belong to the luxury segment, their sales volumes vary dramatically. Luxury goods markets have seen strong growth over the last several years and show high returns. There are more millionaires and billionaires in the world today than ever before. The price trend for luxury goods over the last 25 years is interesting. The average price of exported Swiss watches has increased by around 250% since 1990 [39]. Some luxury goods makers such as Bentley are trying to take advantage of this trend and improve their sales numbers. Bentley had already boosted its volume in 2013 by 19% to 10,120 units and maintained that level in the ensuing years. In 2016 Bentley sold 11,023 cars.

The world’s largest luxury products group, LVMH, posted an EBIT margin of 19.5% in 2017, and its revenue has grown by around 10% per year since 2007. The Swiss luxury goods firm Richemont, the number two in the world, had an EBIT margin of 16.6% in the fiscal year 2017. Its average annual revenue growth since 2007 is around 9.2%. Profit and growth are the drivers of shareholder value [40]. The market capitalizations of these two firms reflect this. LVMH’s sales of $52 billion and a pre-tax profit of $10.2 billion in 2017 helped sustain a market capitalization of $144.89 billion (as of February 2018), which is four times the firm’s 2007 market cap of $35 billion [40]. Richemont had a market cap of $51 billion on sales of $13 billion and a pre-tax profit of $2.2 billion [41]. That is likewise more than three times its value in 2007. Despite their attractiveness with regard to profit and growth, luxury goods remain a niche market, albeit an extremely lucrative one.

2.6.1.2 Management

Product

Luxury goods must offer the highest performance and the best quality across all attributes. That applies to functional, emotional, and symbolic attributes. Johann Rupert, the chairman of Richemont, says: “We understand that we have to produce exciting and innovative products combined with excellent service to meet the demand of an ever more discerning clientele” [42]. They combine perfection in detail and opulence with excess in many facets. Burmester, which makes luxury audio systems, has developed and patented a device which can “clean” electricity. The “power conditioner” preserves and improves sound quality by filtering out the slight residual DC current mixed with the AC current from the power mains. Luxury goods do not necessarily differ from premium products in terms of functional performance. An international study of 28 leading manufacturers of luxury goods revealed that brand image, quality, and design are the main differentiation criteria, not higher functional performance [43].

Personalized service is an integral part of the luxury goods experience. At Burj Al Arab, guests staying in suites have their own butler team available 24 h a day. Leica manufactured gold-plated cameras for the Sultan of Brunei. Each year, Louis Vuitton produces around 300 custom-made special editions for prominent or exclusive customers. The process takes between 2 and 4 months for each piece. Such products include cases for two champagne flutes or for a collection of valuable batons. Things which would be considered extras for premium products are standard for luxury goods.

Luxury goods can actually have some conflicts when it comes to ethical attributes. The Bugatti Chiron, whose 16-cylinder engine delivers 1500 horsepower, has a price tag of $2.7 million. But similar to a private jet, the Chiron is certainly not considered an environmentally friendly vehicle.

Handmade is another hallmark of luxury goods. By nature, hand manufacturing limits production volume but gives the product a personal and individual character. In order to maintain full control over quality and the production process, luxury goods manufacturers tend to be highly vertically integrated and avoid outsourcing. They seek to apply strict controls of their supply chain. Hermès even has its own cattle farms and stitching departments. When Montblanc decided to enter the market for luxury watches, it added its own handcrafting facility in Switzerland. Some customers become so devoted that they make pilgrimages to such facilities. This intensive focus on handmade production and unique pieces offers small firms an opportunity in the luxury segment when they would have little chance of success in the mass market. One example is the Welter Manufaktur in Berlin, which specializes in wall decor. For their customized work, they charge between €1000 and €3000 per square meter. Despite these high prices for wall decor, the German firm has established itself in the international luxury market. It did the walls for the department store Harrods in London as well as the World Trade Center in Dubai [44].

Luxury goods makers rely on dedicated product life cycle management to ensure that their products retain their value. Ideally, a luxury product will appreciate in value over time. Limited editions and collectors’ editions enhance this effect and help provide the desired exclusivity. In 2011, a Hermès Birkin Bag fetched a price of $150,000 at one auction. The original prices for the bags were between $5300 and $16,000.

Price

“Nothing is too beautiful, nothing is too expensive” is the tagline for Bugatti. Nick Hayek, the head of the Swatch Group, says that “there are no limits for luxury goods” [45]. One would imagine, therefore, that pricing of luxury goods could not be simpler: set the price as high as possible. But this simplicity is an illusion. In reality, price management for luxury goods demands very deep knowledge of the customers and the market as well as a delicate balancing act between volume and price.

The price itself is an outstanding indicator of quality and exclusivity for luxury goods. The so-called snob and Veblen effects result in a price-response function with a positive slope over some price intervals [46]. In other words, price increases lead to higher, not lower volumes. Profit rises due to the simultaneous effects of higher unit margins and higher volumes. Such cases really do occur. Delvaux, a Belgian manufacturer of exclusive bags, undertook a massive price increase as part of its repositioning. As a result, sales volumes rose sharply because customers began to view the products as relevant alternatives to Louis Vuitton bags. The effects of a luxury positioning are not limited to consumer goods. The effects can happen for industrial goods as well. The “Hidden Champion” Lightweight, which produces luxury carbon wheels, sells them in sets which cost between €4000 and €5000. These are not meant for the consumer market but rather for professionals. Lightweight does not grant any discounts. Yet demand for the wheels continues to rise [47]. Similar performance attributes played a decisive role in Porsche’s price setting for its innovative line of carbon brakes. Within the company, the price of $8520 as an option for the Porsche 911 model was initially viewed as too high. But the market accepted the price, exhibiting high demand for these yellow brakes. Relative to the usual red brake discs, the yellow ones signaled the status of the car owner and thus served as a symbolic attribute. Despite the considerable price premium, the carbon brake sets became a “must have” for many Porsche 911 owners [48].

The part of the price-response function with the positive slope, however, is not relevant for price setting. The optimal price always lies along the negatively sloped portion of the curve. Luxury goods manufacturers need to know their price-response functions if they want to reach that optimal zone for price setting. Without this knowledge, they are stumbling around in the dark.

In order to support the very high price levels, companies usually limit production. This decision is made up front and communicated to the market. The limiting of an edition therefore becomes binding. Violating this self-imposed limit, for instance, in the case of unexpectedly high demand, can be a severe breach of consumers’ trust. Thus, Bugatti plans to make no more than 500 Chiron vehicles. Montblanc restricts its series of fountain pens dedicated to US presidents to 50 pens per president. Depending on the design, such pens cost $25,000 and up. Very expensive watch models are often limited to 100 pieces or fewer. A. Lange & Söhne made only six units of the most expensive watch at the 2013 Geneva Watch Salon. The price tag was just under €2 million apiece.

Long waiting lists and delivery times enhance the impression of both scarcity and enduring value. Patrick Thomas, the former CEO of Hermès, described the phenomenon: “Indeed we have to deal with a paradox in our branch: the more desirable you are, the more you sell. And the more you sell, the less desirable you are. That is why at times we stop the production of a tie once it becomes too successful. Simply because success may denote triteness” [49]. Some luxury goods manufacturers carefully select their customers in order to prevent the wrong customers (e.g., seedy guests at a luxury hotel) from harming the brand’s image.

The joint setting of prices and volumes for luxury goods is fundamentally different from the approach taken in other markets. In raw commodity markets, suppliers must accept the prevailing price and can only decide how much volume to put on the market. In non-commodity markets, the supplier sets the price, and the market decides how much volume it is willing to absorb. In luxury goods markets, suppliers set both the price and the volume. This combination requires a very high level of information and carries considerable risks. The following real-world case illustrates this. A luxury watchmaker presented a new watch at the watch trade fair in Basel (the world’s largest) and limited volume to 800 pieces. Because the preceding model was highly coveted, the watchmaker raised the price for the new model by 50% from €16,000 to €24,000. At the trade fair, the company received 1500 orders for the new model. At a price of €24,000 and a total run of 800 timepieces, the company would have generated €19.2 million in revenue. If it could fulfill all 1500 orders placed, revenue would be €36 million. If the company had set the price at €36,000 instead of €24,000 and still sold out the originally planned run of 800 units, revenue would have been €28.8 million. The difference between €28.8 million and €19.2 million is pure foregone profit. That means the company missed a profit opportunity of €9.6 million. The moral is that poor estimates of volume and/or price can cost a manufacturer a fortune.

It is equally problematic for luxury goods manufacturers to overestimate demand and thus to produce too many units. Such a precarious situation risks price erosion, especially on secondary markets. It is difficult to reconcile strict production limits with volatile demand. Manufacturers use certain approaches to strike a balance. One is bundling. De Beers has done that for years with diamonds. Customers are offered a mix of higher quality and lower quality diamonds at a set price. The customer must then make an all-or-nothing decision on the bundle. They cannot cherry-pick. Watchmakers take a similar approach. Let us assume that Model A is in high demand and Model B less so. The manufacturer has rigid production capacity for each model. One dealer orders 20 Model A watches, but does not want to buy any of Model B. The watchmaker offers ten units of Model A, but only on the condition that the dealer also buys five units of Model B. The prices are nonnegotiable. From the manufacturer’s perspective, this approach is understandable, but has a downside: the Model B watches will probably end up in secondary channels, where sales can jeopardize the consistent price levels the watchmaker works so hard to establish and protect. The ultimate cause of such price declines and inconsistencies is the miscalculation of supply and demand. This situation is very problematic for luxury goods manufacturers. First, price erosion can lead to massive frustration among customers who have paid full price. Second, these effects damage the brand image. Price stability, continuity, and consistency are indispensable for luxury goods. The myth of luxury goods is that they are everlasting and that is incompatible with price volatility. Ideally, prices for secondhand luxuries rise over time. Some customers therefore view luxury goods as investments. The prices of luxury goods usually reflect all performance attributes. Comprehensive service and other performance attributes (e.g., lifelong guarantees, club memberships) are built into the price. In other words, prices for luxury goods are usually “all inclusive.”

Distribution

A key aspect of distributing luxury goods is selectivity. Luxury goods companies often have only a small number of carefully chosen outlets or dealers per country. The watchmaker A. Lange & Söhne has only 25 dealers in the United States and 15 in Japan. In Germany, there are only four cities where you can purchase a Rolls-Royce. The exclusivity in the sales channel reflects the exclusivity of the product. This applies not only to the number of stores or outlets but also to a brand’s quality standards in terms of design and appearance of the sales floor, as well as the competence and discretion of the sales staff. To maintain these quality standards, manufacturers must exercise strict supervision and quality control.

The striving for high-quality standards and price enforcement have led luxury goods manufacturers to rely more and more on their own stores. Groups such as LVMH or Richemont already generate a large share of their business through their own stores. Luxury brands benefit more from their own retail stores and sales networks than from wholesale distribution. Although wholesale overall still accounts for 64% of sales of luxury brands, sales in retail (at current exchange rates) is growing more than twice as fast as sales in wholesale [50]. Revenue at the Italian luxury fashion group Prada shows a similar breakdown. The group currently generates 82% of its total revenues through its 613 self-managed stores [51]. Shifting to company-owned or company-managed stores is very important for companies which want to make the leap from premium to luxury. Luxury goods makers also use the agent model, under which, similar to the gas station business, the dealer acts as an agent representing the manufacturer. Under both systems, the manufacturer maintains complete control over all parameters, including price.

For a long time, luxury goods companies shunned the Internet as a sales channel. Personalized service and the shopping experience in an exclusive store seemed too important. Most companies have therefore limited themselves to the presentation of their products online. Only recently have some established online stores. The growth of online sellers such as net-a-porter.com or mytheresa.com has shown, however, that luxury goods buyers do make purchases online. The Internet and social media are becoming increasingly important for the luxury goods industry, even as brands wrestle with how to maintain the allure and exclusivity of “luxury” in a digital world. E-commerce in luxury grew to 9% of the market in 2017, more than doubling its share 5 years ago [50, 52].

Communication

Luxury goods require sophisticated and superior advertising, selective media usage, and collaboration with the best ad designers and photographers to maintain their brand image and convey their value to potential customers. Manufacturers often allocate up to a quarter of overall revenue to communication budgets. Public interest in luxury goods is generally high. Marketing makes strong efforts to reach out to customers through editorial content and background stories. The attractiveness of luxury products depends to a certain extent on their inaccessibility—while they are highly desirable to many, most people cannot afford or do not have access to them. The companies consciously cultivate this aspirational tension. Public relations and sponsoring therefore play a more prominent role than classical forms of advertising. The communication is often supported by spectacular actions or events.

Tradition is an important facet of a luxury good’s image and communication. A brand’s image is refined and solidified over time, and current advertising cannot replace a rich brand history. The Richemont and LVMH groups demonstrate the power of tradition in lending gravitas to their luxury brands. The average age of Richemont’s brands is 120 years, while those of LVMH are on average 110 years old. Classic may mean old, but not obsolete.

Price almost never appears in communications about luxury products, at least not explicitly. Rarely do luxury brands list price points in brochures, on homepages, or in stores. Prices are only available on request. This quasi-secrecy surrounding prices is a further signal that luxury goods are about pure value; price is not displayed as a point of interest. Implicit in this behavior is the idea that anyone who needs to ask for the price is not a “real” luxury goods customer. Charles Rolls, the founder of Rolls-Royce, put it this way: “If you have to ask what it costs, you cannot afford it” [53, p. 229].

Configuration of marketing instruments for luxury price positioning

Product | Price | Distribution | Communication |

|---|---|---|---|

• Extreme in quality and performance, especially on emotional and symbolic attributes • Comprehensive, personalized service • Highest exclusivity • Own manufacturing, often handmade or customized (very little outsourcing) | • Very high • Consistent across channels to retain value • No discounts whatsoever • Limited editions; price and volume planned concurrently | • Extremely selective distribution • Strict control of sales channels • Trend toward company stores or agent systems • Rather low but increasingly significant online sales | • Sophisticated advertising • Selective media usage • Heavy use of print (>60% of the ad budget) • Emphasis on PR, editorial content, reports, sponsoring, and special events • Emphasis on tradition • No active/explicit price communication |

2.6.1.3 Opportunities and Risks

Luxury goods markets are extraordinarily attractive because they combine high growth and high profitability. But conquering these markets is anything but easy. In the luxury sector, one finds primarily French, Italian, and Swiss firms. For luxury cars, the German and British brands are well represented. New players often struggle to establish the prestige and demand of true luxury brands.

Top performance on functional attributes is table stakes, but in and of itself not sufficient for success. The products must also deliver very high emotional and symbolic value.

In order for luxury goods to be profitable, they need to reach sufficient volumes—without producing such high quantities that they cheapen the brands. One risk is that the production volumes remain too small to be profitable (“curse of the small volumes”).

On the other hand, loss of exclusivity poses a threat. Luxury goods are by their very nature elitist. Exclusivity plays a key role. Growth strategies and expansion plans which dilute a brand’s exclusivity must be avoided. This applies to horizontal expansion into new product categories (brand extensions) as well as vertical extensions, i.e., down-market line extensions. Watering down the brand is extremely dangerous for luxury products. The expansion may pay off in the short run, but long term it can lead to the trivialization of the brand.

More and more, luxury goods makers are opening their own stores in order to maintain control over prices and the quality of the sales experience. This opens up growth opportunities but requires a massive capital investment and the assumption of additional risk.

2.6.2 Premium Price Position

2.6.2.1 Basics

A premium price position means that a product or service is offered at a price which is noticeably and sustainably above the market average. There are premium products and services in almost every sector. On the consumer side, these include Mercedes-Benz and Lexus (cars), Miele (washing machines), Nespresso (coffee), Starbucks (coffee shops), Clinique (cosmetics), and Apple (consumer electronics and computers). Premium services include Singapore Airlines and Lufthansa, private banks, and hotel chains such as InterContinental and Four Seasons.

But premium products are by no means limited to prestigious consumer products. There are also many premium offerings in B2B industries. We often hear the expression “We are the Mercedes-Benz of our industry” in connection with industrial goods. Midsized world market leaders, the so-called Hidden Champions, usually have a price level of 10–15% above the market average and still rank as global market leaders [54].

For a premium price position, the quality, competence, or uniqueness of the supplier is at the forefront of the customer’s interest. Price is not. The cost differences between competing offers are typically smaller than the differences in the perceived value and the resulting willingness to pay. The latter is systematically exploited through the premium price. A board member of a premium automotive company explained the premium position: “Our prices should be 12–16% above the market average, but our costs should only be 6–8% higher. This difference is where the music plays.”

Price difference between market average and premium prices, Status: January 2018

Product | Medium-price position | Premium-price position |

|---|---|---|

Chocolate (3.5 oz) | Cadbury: $1.93 | Scharffen Berger: $4.99 (+159%) |

Ice cream (35 oz) | Breyers: $2.18 | Ben & Jerry’s: $8.68 (+298%) |

Pencils (each) | General’s Kimberly Graphite Pencil: $0.95 | Faber-Castell 9000 Pencil: $2 (+110%) |

Men’s dress shirt (white) | Alfani: $52.50 | Hugo Boss: $95 (+81%) |

Smartphone | Huawei P10 (64 GB): $449 | iPhone X (64 GB): $999 (+123%) |

HDTV (55 in.) | Toshiba: $449.99 | Samsung: $1099.99 (+144%) |

Midsized car (base model) | VW Passat: $22,995 | Mercedes-Benz E-Class: $52,950 (+130%) |

Hotel, Miami (one night, classic room) | Hilton Miami South Beach: $217 | Four Seasons $478 (+120%) |

Premium products are not only superior in terms of functional performance; they should perform strongly across emotional, symbolic, and ethical attributes as well. They are characterized by high quality and an outstanding service package. Innovation is often the basis for their superiority. The high price itself can become a positive attribute. This effect can come from price serving as an indicator of quality as well as from the social signals (Snob or Veblen effect) it sends. Through the purchase and use of a premium product, customers consciously separate themselves from the crowd, but without fully removing themselves from mainstream society (as might happen with luxury goods).

2.6.2.2 Management

Product

Given the quality expectations, the product itself plays a central role in premium price positioning. Superior competencies along the entire value chain are indispensable, from innovation to the procurement of raw materials. It also covers stable production processes and above-average capabilities of the sales and service organizations. In no other product category—not even for luxury goods—is innovation more important than for premium products. This is because the unique selling proposition (USP) of premium products is often first established through innovation.

In the smartphone industry, groundbreaking innovations (front camera, retina display, HD camera with optical zoom, stereo speakers, 3-D touch) are generally introduced in premium models (such as the iPhone) and then spread to the average and lower price ranges. As a result, the competitive advantage derived from any given innovation is only temporary, so premium suppliers face constant pressure to innovate. Some brands stress this emphasis on constant innovation in their advertising claim. The premium household appliance manufacturer Miele has used the slogan “forever better” since its founding in 1899. This slogan represents the firm’s guiding philosophy. Miele has always strived to be better than its competitors and continually improves its products.

Nonetheless, innovation isn’t the only successful premium strategy—a company can also focus on remaining true to what has worked well. One calls this variant the “semper idem” (always the same) strategy. “Semper idem” is actually the motto of Underberg, a digestive famous in German-speaking countries. The USP of such products, such as Chivas Regal, derives from the fact that the product never changes. Constancy is an advantage. But this applies only to the product itself. The company has to adjust and adapt its marketing methods and its production processes. Premium products also require a level of service which is both comprehensive and of a similar quality as the product itself. To deliver this, companies require highly qualified employees both internally and at its sales and distribution partners.

Price

The comparatively high price is an integral feature of a premium product. The price cannot become a ping-pong ball for discount actions, special offers, or similar price-driven measures. Premium suppliers must place a high value on continuity, price discipline, and price maintenance. Wendelin Wiedeking, the former CEO of Porsche, explains: “Our policy is to keep our prices stable, in order to protect our brand and avoid a decline in the residual value for used Porsches. If demand falls, we cut our production, not our prices.” The current marketing decision-makers at Porsche, Bernhard Meier and Kjell Gruner, have a clear philosophy on this point: “We always want to sell one vehicle fewer than the market can absorb, in order to remain true to our brand promise of high exclusivity and high retained value. We are not volume driven, but rather obligated to an enduring business” [55].

Sharp variations in price are not compatible with the sustained high-value image of a premium product.

Temporary price reductions will frustrate or anger customers who purchased the product at its normal (high) price.

For durable goods, price actions can jeopardize prices for used products. The residual value is an important purchase criterion for these kinds of products. A decline in residual value can diminish willingness to pay for new products.

Recommended prices for resellers are appropriate for premium products and should be enforced. The manufacturers of premium products should be resolute in preventing the use of their products as loss leaders, even though this may not be easy to achieve for legal reasons. Retailers and resellers continually try to circumvent the efforts of manufacturers to maintain resale price discipline.

Above all, manufacturers should resist the temptation to lower their prices. It could certainly be the case that the price elasticity for a premium product is very high when the price cut is massive, leading to a sharp rise in sales volume. After repeated use of this tactic, however, the product could lose its premium status and become a mass-market product. An example of this is the clothing brand Lacoste. The French professional tennis player René Lacoste founded the company in 1933 to sell sports shirts he designed. The recognizable crocodile emblem stood for exclusive prestige, and the Lacoste shirts achieved high prices and margins. US President Dwight Eisenhower and other celebrities wore Lacoste shirts in public. For 50 years, Lacoste was a brand associated with high social class. Over time, though, Lacoste became a mass product. The prices fell. As a consequence, sales volume declined, triggering more price reductions and ultimately lower profits. This case sheds light on why price discipline for premium products is so important.

Distribution

Premium product distribution rests on exclusivity and selectivity, beginning with control over how the product is presented. This goes beyond the visual presentation to include the qualifications and appearance of sales personnel. Implementing this maxim in practice often proves difficult. In industries such as clothing or consumer electronics, it is not uncommon for premium products to be sold in an environment dominated by medium or even low-priced products, even though that is unlikely to be in the best interests of the premium manufacturers. Increasingly, premium suppliers are setting up stand-alone “shop-in-shop” spaces within department stores to separate their products from the medium-priced ones. This concept has proven itself and is fitting for a premium price position.

According to Lasslop [56], one should split the distribution hierarchy for premium products into three levels. At the highest level are the flagship stores, whose primary purpose is to “celebrate and worship” the premium brand. Examples of such stores are those of Apple, Nike, or the coffee brand Nespresso. Achieving high revenue is not the main purpose of these stores. Rather, they showcase the brand, as the term “flagship” implies. They should create a destination for consumers to immerse themselves in the brand and its aspirational, premium nature. The second level is franchised stand-alone stores in which the manufacturer still maintains control overall key parameters. The third level of the distribution hierarchy is comprised of specialty retailers and upscale stores, such as Nespresso boutiques in Sur La Table or Macy’s in the United States. The trend toward the “shop-in-shop” has taken hold in particular in upscale stores. Because of the demands placed on these intermediaries, their selection follows very strict criteria. In exchange for complying with the manufacturer’s demands for a high-quality presentation of the product, a sophisticated ambience, and highly qualified personnel, the selected intermediary receives a certain level of territorial exclusivity. In some cases, the manufacturer adopts an exclusive distribution system.

The distribution of premium products through a national network of factory outlet centers (FOCs) should be viewed critically. True stand-alone factory sales stores, which operate only locally, expose the image and price of premium products to less risk. In sectors where customers don’t tend to have strong loyalties to a retailer (e.g., textiles, furniture, and household appliances), factory outlet centers can be an interesting distribution option. These centers tip the balance of power in retail, which often favors the store, slightly in favor of the manufacturer. Manufacturers prefer to offer goods from the previous season at FOCs rather than the latest models.

While the luxury price segment still has a limited online sales presence, due to its inaccessibility and exclusivity, the premium segment is increasingly using alternative distribution channels. Online sales now account for around 17% of the revenue for premium brands [57]. When they buy premium products or premium brands, customers still expect outstanding service, customer orientation, and customer care [58], which are prerequisites for a high willingness to pay in this segment. But these service aspects are often very hard to fulfill online. Thus, the opportunities for success in online distribution channels depend on the sector and on how explanation-intensive the product is. For example, consumers are rather willing to purchase an iPhone upgrade online than a new washing machine or furniture.

Communication

Due to the relevance of branding for premium products, it goes without saying that communication is very important. The content of the communication focuses primarily on exclusivity, prestige, and continuity. In addition to classical advertising, premium products are increasingly relying on “below-the-line” activities. These include public relations, event marketing, and product placement. James Bond drives a BMW 750iL in “Tomorrow Never Dies.” BMW marketed the launch of its i8 hybrid electric vehicle in conjunction with the Mission Impossible film “Ghost Protocol” by having Tom Cruise drive the car. The slogan “Mission to drive” connects the reputation of the film to the automobile. Apple products also appear prominently in many films.

The communication of premium products derives from performance, emotion, and social prestige. Price stays in the background. If a company succeeds in establishing a premium image, the price plays a secondary role in the purchase decision.

Configuration of marketing instruments for premium price positioning

Product | Price | Distribution | Communication |

|---|---|---|---|

• Outstanding functional performance and quality • Comprehensive service package • High importance of emotional, symbolic, and ethical attributes | • Sustaining a high relative price • Uncompromising on discounts and promotions • Price discipline and maintenance are particularly important • Clearance sales only for fashion products | • High exclusivity and selectivity • Establishing control over the presentation of the product; high demands placed on the seller/retailer • Selective, but increasing level of online sales | • Emphasizes non-price factors • Continuity of the message • Use of below-the-line activities (e.g., product placement) |

2.6.2.3 Opportunities and Risks

Relatively low-price elasticities in the upper price ranges allow for higher premiums.

Because customers in the premium segment place higher value on performance attributes, there are more opportunities for product differentiation than in mass markets. Every performance attribute is a potential competitive advantage. Canoy and Peitz [60, p. 307] assess these opportunities from the customer perspective: “Customers’ evaluations are more dispersed in the high-quality range than in the low-quality range.”

The frequency and the danger of price wars are lower in the premium segment than in the lower price ranges. A “price warrior” in this segment risks ruining its brand image.

Rising wealth and rising incomes are driving growth in the premium segment. Customers are trading up from the medium segment to the premium segment.

Financial crises can cause shifts in demand from the luxury segment to the premium segment.

A greater emotional awareness among customers can be observed. The demographic transformation—or more specifically, the aging of society—leans in that direction. According to an Accenture-GfK study, many older consumers prefer expensive products and sales channels [61].

A particular challenge lies in achieving and maintaining a high level of quality and innovation. A purely image-based differentiation will not endure if the product or service does not deliver the quality to back it up. Quelch [62, p. 45] states: “Mere exclusivity without quality leadership is a recipe for failure.”

The brand faces similar risks. If a company fails to position or maintain its brand at the level that premium customers expect, it is headed for trouble. The VW Phaeton could serve as the poster child for this. The VW brand proved too weak in competing against BMW or Mercedes in the premium segment.

Products upgraded from medium pricing also pose risks to existing premium products. If the aspiring company improves both the product’s quality and its image, that product can attack premium products from below. Such trade-ups occur in many markets. Toyota’s Lexus is a telling example.

Managers of premium products must resist the “temptation of large volumes” and the growth they promise. One of the most effective and quickest ways to destroy a premium price position is to cut prices in order to reach the mass market, i.e., to hit higher volume numbers and achieve wider distribution.

For consumer durables, the secondhand market can pose risks. Premium products enjoy a high level of popularity on secondhand markets. The Internet has aggravated this problem. This is well-known in the market for cars. A flourishing secondary market can suppress demand for new products and exert downward pressure on the prices for new products. Premium manufacturers should keep a close eye on the secondary market and intervene if necessary.

The premium position implies higher complexity and higher costs. A high level of performance does not come at low costs. Thus, there is the risk that costs get out of control. For premium products, one must always make sure that higher prices overcompensate for additional costs. Costs which do not contribute to an increase in customers’ willingness to pay should be avoided.

2.6.3 Medium-Price Position

2.6.3.1 Basics

A medium-price position means that from the customers’ point of view, a product or service has a middling level of performance and a consistently midrange price, relative to the market average. A medium price falls within the customers’ perceived market average. The same applies to the level of performance. Products with a medium-price position typically include classic branded products which have often helped to set standards in their respective markets. Examples include Buick, the household goods manufacturer Whirlpool, or retailers such as Kroger and Tesco. Products and brands in the medium-price range have been and remain very significant. Characteristic aspects comprise brand, the promise of quality, image, becoming synonymous with an entire category (Kleenex, Q-Tip), and ubiquity.

As discounters penetrate further into markets, the medium-price position has come under attack, but in the recent past, there has been a countertrend—the medium-price position is getting stronger again. In terms of overall volume and value, the medium-price range still forms the largest segment in many markets. Brands such as Gap or American Eagle achieved success with a medium-price position. Importantly, their level of quality distinguishes medium-priced retailers from low-priced competitors such as H&M, Forever 21, or Primark, combined with current, up-to-date designs. The medium-priced retailers do not offer top cuts or materials such as Hugo Boss or Ralph Lauren do, and the symbolic performance does not stand out as much, but the price is also noticeably lower than for premium products. Within fast-moving consumer goods, there are numerous product categories in which the medium-price position is dominant. Some 60% of the market for noodles falls in the medium-price range [63].

2.6.3.2 Management

Product

Good and constant quality is the predominant characteristic of medium-priced products. In comparison to low-priced products, a supplier should pay attention to establishing customer preferences based on performance. This affects primarily the components of the functional attributes, such as technology, the degree of innovation, and reliability or durability. Medium-priced products should also differentiate themselves in terms of packaging and design (emotional performance) as well as at a rudimentary level along symbolic attributes. This applies above all to consumer products. The management of the brand therefore is highly important. While medium-priced products are less differentiated than premium products, they offer more variants and models than low-priced products.

If variable unit costs fall due to scale and experience curve effects, the company needs to decide whether to reduce prices or improve performance. In many cases, the company with a medium-price position opts for improved performance in such a situation, whereas a manufacturer of low-priced products would react by lowering the price. This is done in order to further expand the competitive advantage of “superior performance.” For this reason, prices in the medium-priced segment of the computer industry generally do not fall but instead offer more performance and more accessories from generation to generation for the same price. A committed low-priced supplier would instead tend to cut prices in order to reinforce the “low-price” competitive advantage.

Price

Consistent with the brand image and stable quality, many suppliers of medium-priced products try to maintain a steady price level as much as possible. They are trying to keep price competition at the retail level in check. In order to stem the frequency and the extent of special offers or discounts, medium-priced suppliers practice active price maintenance. The goal is to harmonize end consumer prices within a certain range (price corridor). Because vertical price-fixing is forbidden, it is not possible to steer end consumer prices directly when the products are sold through distributors or retailers. Nonetheless, the manufacturers definitely exert some influence over end-customer prices. The associated measures include identifying loss leaders, tracking the flow of goods in order to prevent gray imports, buying up reduced price goods, appealing to the trade partners, limiting on deliveries, or incentivizing channel partners to maintain and enforce recommended prices. Legally, this is a gray area in which the power of the manufacturer has been declining.