Aspie Mentors’ Advice on Being Tested for Asperger’s/HFA

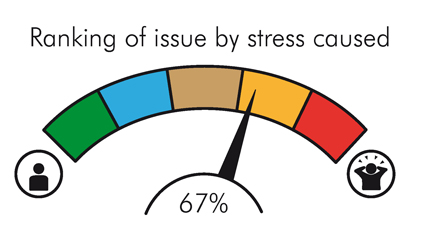

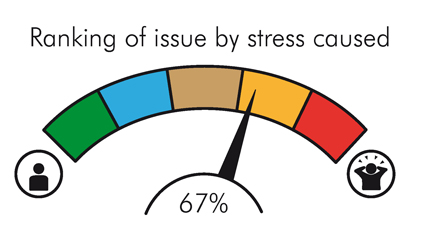

Stress Ranking: 17*

*Please see “The 17 Stressors” at the end of this eBook to put this research in context.

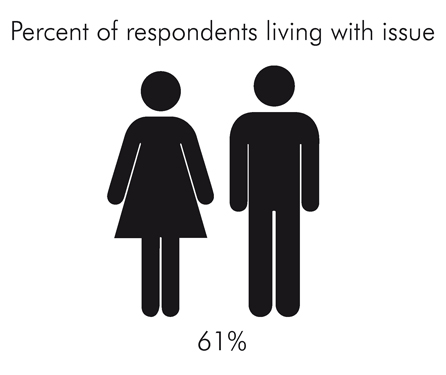

Where some people diagnosed with Asperger’s/HFA may feel relief or liberation, others have issues with the label. Some examples of these issues include: feeling sad, feeling depressed, feeling hopeless, and feeling angry at “being different.” Do you have concerns about your diagnosis?

Charli Devnet

Aspies diagnosed in midlife speak of their sense of relief to finally have a label to apply to themselves, their liberation from the shame of the past, the empowerment that self-knowledge brings, the freedom to be proud of themselves at last. It is as if they have found the missing piece of the puzzle, the clue that solves the mystery, and the roadmap that leads home. This is how it was with me.

When I was a child in the 1960s, the diagnosis of Asperger’s was unknown in the United States and the term “autism” implied “mentally retarded.” No one believed that a person with a high IQ could actually be autistic. Nevertheless, I always knew I was different from the other kids. My teachers knew it, too. They called me a “gifted child” because of my intelligence, but I was also referred to as a behavior problem, emotionally immature or, simply, a misfit.

All too soon, this little savant fell flat on her face. With no diagnosis, my shortcomings were ascribed to character flaws. As a child, I was annoyed and angry to be persistently misunderstood. It was all their fault. However, as the years unwound and my losses piled up, I began to internalize the comments I heard. No friends, no dates? No job? Is life one disaster after another? It must be all my fault. Sure, I am selfish, stubborn, lazy and rude. Pride flew out the window. I shuffled through life, eyes downcast, shouldering a heavy burden of shame, a loser in life’s lottery.

Diagnosis allowed me to hold my head up again. That is the experience of a late-diagnosed Aspie. However, had I been diagnosed as a child, I would certainly not have felt that way.

As a child, I did not like being singled out, either for praise or condemnation. I did not even like being called “gifted.” My one desire was to be considered just one of the kids. “Being different” was hard to bear. That was why the bullies chased me, on the one hand, and why the teachers sent me to the principal’s office, on the other.

Thus, I can understand how receiving a diagnosis of Asperger’s before one is ready may make one feel stigmatized. It cuts off the prospect of one day blending in. You are sentenced to a lifetime of uniqueness.

For those who have been diagnosed before their time and found it unsettling, I offer this advice: diagnosis does not make you an Aspie. It’s like switching on a light in a dark room. The light allows you to see, but does not actually change what is already in the room.

It’s always better to know than not to know. We Aspies like acquiring knowledge…and self-knowledge is the root of all wisdom. Once you know and accept yourself as you are, you can move forward with your life and flourish. You need not waste valuable years, as many of us did, trying to fit yourself—a square peg—into a round hole.

If your goal truly is to be a face in the crowd, it may still be possible. I know adult Aspies who seem to me almost neurotypical. They have steady jobs, stable marriages, friends and families. I am tempted to ask them, “What makes you an Aspie?” (It is impolite to ask that question.)

Moreover, labels don’t matter as much as you think, out here in the real world. Tell people you have Asperger’s and half of them will stare at you blankly. Others will smile and say, “You must be a genius, then.”

Qazi Fazli Azeem

There is no greater feeling in the world than to know that you are not alone…that there are others out there like you—others that you can meet and learn from. We are a community, an international one. We exist all over the world, in all cities and countries, and come from all religions and groups of people, and we are growing.

We are Asperger’s, and we will change the world together.

Ruth Elaine Joyner Hane

Leaving my session with a psychologist who specializes in autism, I had mixed feelings. I was happy to have a diagnosis, but sad to have lived so long without knowing about my neurological difference. As I pressed the down button for the elevator, another woman joined me. It was Friday afternoon on a beautiful summer day in Minnesota. The attractive person standing next to me, I guessed in her late twenties, seemed anxious. “So, do you have exciting plans for the weekend?” she asked, as we stepped into the elevator. “No, do you?” “Yes! I’m going to a rock concert!” I contemplated, given my new diagnosis, what I would have said if she had inquired if I had plans for the rest of my life.

It was because of doubters who told me that I probably did not meet the criteria for autism that I made an appointment. My psychologist disagreed with the critics, saying she had never been more certain because I met almost all of the criteria for High Functioning Autism. She asked, “How have you learned to accommodate so well?” I considered the question, “I don’t know, but I’ll think about it.”

Nearly 20 years have passed since my diagnosis. I believe I have learned to accommodate my differences because of the guidance of others. I grew up in a small town where reasonable variances were accepted and tolerated. My excessive energy, insatiable curiosity, undiagnosed dyslexia and resistance to change were just the way I was. Many of our neighbors were professors at the local college. When I had a question, I just asked. If my question was not in their field of study, they referred me to a colleague. I learned about horticulture, home economics, animal husbandry, English, biology and mathematics by asking questions. After I heard a song about the bones of the body, I asked, “What is a back bone?” Dr. Grebe showed me a skeleton in his biology lab and I touched the bones of the spinal column.

My greatest challenge is social. It takes an effort to attend social events, reciprocate with neighbors and foster friendships. After I get to know someone, I usually disclose my diagnosis. I have learned that no matter how much effort I put into acting normally, I omit something or offend another person. I become especially sad when I cause rifts in our family. Usually, miscommunication is from not using enough words, making assumptions, or not understanding another perspective.

I enjoy a challenge. I was happy to receive a diagnosis because it gave me an opportunity to learn all that I could about autism. I began to read, research, meet professionals and learn how to make my life easier. I volunteered, gave workshops, wrote and started social groups. I learn from others diagnosed with autism at conferences, in groups and on the internet.

I feel fortunate to have developed friends among my peers. To an observer, it would appear as if autistics are casual acquaintances, since we tend to omit the usual social niceties, and progress to an exchange of information and ideas, usually standing apart at arm’s length. Many on the spectrum do not tolerate hugs or touching, while others seek deep hugs and some prefer light pressure. We learn to directly ask before we assume how to greet or touch one another. The unspoken bond of experiencing life differently connects those of us with autism.

Scientists are developing subtypes in autism. With a more specific diagnosis, we can find others who are like us. And, perhaps, find many lifelong friends.

Henny Kupferstein

Those who do pursue a formal diagnosis find it to be life altering, in a good way. After the inevitable grieving process, one discovers that among like-minded adults there seems to be a rambunctious group of delightful people. If you do have the luxury to meet up with them, your experience will be a pure delight. Newly diagnosed people discover that indeed they now belong to a sub-culture, one they are very much comforted to be a part of. Therefore, I highly recommend a formal diagnosis to boost-charge that social connection and deep emotional bond with others.

Another reason for a formal diagnosis is for paperwork stuff. You might find it helpful to apply for social security based on disability if you are in desperate financial straits. This can be a temporary process until you can get yourself on your feet again. With over 90 percent of us being unemployed, I would say this is a wise step. I mention this, because you need to tell your evaluator that you plan to apply. They will then know exactly what kind of information to evaluate for, and how to write the report accordingly.

Quite similarly, if you plan to continue your education after high school, you will need this formal diagnosis. But you also must tell your clinician that you are applying for college, and would like to be assessed for accommodations. This is very important because you must submit all this paperwork to your college, and they do not have to employ experts to evaluate you. Additionally, the college will only accommodate exactly to the letter of the written accommodation recommendations. So make sure you mention it to the clinician. They are well skilled and knowledgeable on what worked and what didn’t for others, provided that you land by the office of an expert skilled in diagnosing Asperger’s. Otherwise, you set yourself up for a long string of disappointments and horror stories.

James Buzon

I suspected for a long time that I was different in ways that didn’t just amount to being “unique.” I think my first moment of realization was when I was in kindergarten. I remember the odd sensation of not quite being able to understand what other children were saying, like I was trying to grip something slippery that would not stay still. I remember being called weird. It was my first experience of things just not feeling right.

I had seen Rain Man with Dustin Hoffman as Raymond Babbitt. Once or twice, I thought about what autism was, and sometimes wondered if I was autistic. I didn’t have those special talents that seemed to be displayed by him. I just knew that I felt different, and my way of interpreting the world was different. To those observing me, I just needed to work harder, to grow up and to “apply myself.” The phrase “everyone has bad days” seemed to apply to every day.

I kept pushing, and somehow made it through my required years in public schooling. All the while, I was reading self-help books, and to others, I seemed to have many friends going through high school. I had quite a few friends, and was happy to feel wanted. However, I still felt different. No matter what was happening around me, I felt disconnected.

It wasn’t until I went to college and really began to address my feelings of anxiety and depression that I found a therapist who knew about Asperger’s syndrome. I read up on Temple Grandin, and started to see that I could very well be autistic. At the time, I didn’t take it seriously; I was still trying to take care of my self-esteem. The gap between how people viewed me and what I felt inwardly seemed to grow wider. That disconnect was still there.

After college, things went downhill very quickly. I couldn’t afford to attend a graduate school. On top of being unable to follow the path I had chosen to become a college professor, I was hospitalized for having what was labeled a “psychotic episode.” I started falling further into my depressive state, further exacerbated by the fact that those who believed they were helping me were unwilling to listen to me. I felt like I was talking to a brick wall. Even after getting a neuropsychological test, my doctor and therapist still kept trying to apply labels that didn’t fit.

Finally, I happened upon a book about Asperger’s syndrome. The title was Look Me in the Eye by John Elder Robison. I read that book every chance I could get. Once again, I felt that spark of recognition, and decided I had to try to get some sort of help. My doctor and therapist weren’t helping matters by throwing labels of “schizoaffective” and “schizophrenic” in my direction in hopes they would stick (the two most common psychiatric labels, I later discovered, to be confused with AS). I eventually risked going off of my medications and leaving therapy to prove to myself that they were incorrect.

The next step took a bit longer, mainly because I wasn’t aware of the next step to take. The only thing I knew was that I was neither “crazy,” “stupid” nor “retarded”: my grades and intelligence spoke volumes about my abilities. I finally got the courage to ask my vocational counselor about being retested for AS. Mainly, I wanted my psychiatric label wiped from all paperwork. It was erroneous and misleading. I was given the name and number of a professional familiar with administering neuropsychological tests, and soon had an appointment. As it turned out, my psychiatric label was erased, and I was diagnosed with an Autism Spectrum Disorder.

I was over-the-moon excited! For once, I felt I had triumphed over everyone who had ever told me I was wrong about myself. I felt vindicated. I also felt a bit bewildered, because all of a sudden, I was unsure of what to do next. I had my suspicions confirmed, and I had answers. I suppose that was what I was looking for. I still felt a bit lost.

In time, however, I’ve come to realize that I can use my diagnosis to my advantage. I don’t view it as a “get out of jail free” card, nor any sort of excuse. What I do have is someone on my side in helping me get work when I get back into the “real world” after college. I have a counselor who can be a mediator if I ever need that assistance. In short, I have a lifeline. Anyone on the spectrum needs a lifeline. It may mean the difference between getting fired for being “weird” and keeping that job. Having an actual assessment means that there are services to help when it’s needed.

Most of all, the diagnosis means I’m no longer “weird” or “creepy”; it means I have a different way of seeing the world. It legitimizes my very existence. It lets me ease up on myself when something doesn’t go well socially. It means that I can finally join a community of others like me and use that commonality for support. I recommend those seriously struggling to find themselves to seek out others on the spectrum. I know when I’ve had a bad day that I have friends who know exactly how I’m feeling, because they have been there. I’m no longer alone in my struggles.

REFERENCE

Robison, J.E. (2008) Look Me in the Eye: My Life with Asperger’s. New York, NY: Three Rivers Press.

Jeanette Purkis

I was born way back in 1974. The Asperger’s diagnosis was first available in the English-speaking world in the late 1980s. If you’ve done the sums you’ll see that I couldn’t have had a diagnosis when I was in primary school. In fact, I went through 13 years of schooling without an Asperger’s diagnosis. This meant that school was often very unpleasant, as I had no idea why people didn’t seem to like me and picked on me.

It was very important to me to be popular and included in a group. However, this eluded me for almost all my childhood and teenage years. I had the occasional friend, but I was never quite sure what to say to them or how to behave and they usually gave up and left me alone again. When I was a teenager, I thought that the only way that anybody would like me was if I belonged to a group that they also belonged to. First of all, I belonged to my parents’ rather uncool church. That didn’t do it for me, so I joined an extreme left-wing political group, the International Socialists. I loved being in this group because all the members were older than me. This wasn’t the best group to belong to, though, as I often drank alcohol, used drugs and got aggressive at political rallies.

My need to belong to a group was far stronger than my sense of morality or ethics, and I ended up belonging to a very negative club indeed—that of criminals. I thought that if I did things my criminal friends liked I would be “cool.” It was at this time that I got my Asperger’s diagnosis. Even though that little description of the world as experienced by me and all the other Aspies could have changed my life, it took me over seven years before I accepted that I did, in fact, have Asperger’s syndrome.

I spent those seven years doing stupid and dangerous things just to impress my “friends.” Eventually my life became so chaotic that I decided to make some changes. I did some therapy and enrolled at university. When I was about to start my second year of university, I accepted the truth. I did, in fact, have Asperger’s syndrome. It was a description of the way I experienced the world, of how I saw things and really, of who I had always been. Rather than thinking that the diagnosis was a way for my parents to make excuses for my poor behavior, or that Asperger’s was essentially a diagnosis of “geek,” as I had for years, I now knew that it was correct.

My acceptance of my diagnosis was an acceptance of myself. It was probably the most important step in my maturity, and I’m so glad that I can now proudly say “I am an Aspie.”

TIPS FOR ASPIES

•The Aspie club is an awesome club! There are so many cool people who have the diagnosis. We’re smart, interesting, honest and good. Never be ashamed of who you are!

•Finding out that you are an Aspie when you’re young is fantastic and liberating. Treasure it, as it means that you can make the most of life from an early age.

•People will, and do, like you for who you are. You don’t have to follow a negative group to be accepted. Friends are everywhere. You may wish to start with other Aspies if you’re having difficulties making friends.

Anita Lesko

The decision to seek formal testing is a very personal choice. This may depend on several factors. I personally only see it necessary for work or school purposes. After learning of Asperger’s, I then thoroughly researched it. I knew without a doubt that I had Asperger’s. I’m sure this is the same for everyone else. You don’t need a psychologist to confirm it.

I would definitely see the need for a parent to have their Aspie child formally diagnosed. This would be necessary for the school system to make special accommodations for the child. It also serves the faculty to better understand the behaviors. What might seem like an unruly child might instead be recognized as one who is experiencing sensory overload. That can make all the difference in the world. This would hold true throughout elementary, junior high and high school. In many colleges and universities, they now have special services for students with special needs. You would need your official diagnosis for that purpose as well.

The workplace is the most crucial area of need for the formal diagnosis. People on the Autism Spectrum are protected under the Americans with Disabilities Act. An employer must accommodate any special needs you will have. By having a letter from a psychologist stating you do in fact have Asperger’s, those needs must be met. It will also protect you from being bullied on the job.

Other reasons for seeking a formal diagnosis would be for health insurance reasons, or for being eligible for disability allowance. Obviously the diagnosis is warranted.

Look for psychologists who have a lot of experience with Asperger’s. Not every therapist really knows what it is or how to deal with it. That person is the one ultimately interpreting your test results, so do your research prior to making an appointment, and don’t be afraid to ask questions. Even a visit to the office to inquire in person will help—and that goes for any kind of doctor, for that matter.

I found the several hours of testing that took place over three days both irritating and amusing! I could not believe some of the bizarre tests I was presented with, most of which seemed totally worthless to me. However, these tests are designed to determine how your brain thinks, so just forge ahead and do them, no matter how silly they appear.

Once all test results have been obtained, it will be several days before your psychologist reviews them. They will then talk with you about the findings, and they will also talk with you to make the final conclusion: that you have Asperger’s! You already knew that. Now you have a piece of paper to prove it.

I highly advise everyone to become familiar with the Americans with Disabilities Act. Go to www.ada.gov. This is for both individuals and parents of children with Asperger’s.

Richard Maguire

My view of getting a diagnosis is that we are logical people who need to have things in a framework that we can work with. Getting a diagnosis helps us lots and gives us framework, affirmation and assistance in working out where to go in life.

Behind all this are a lot of personal, life and timing issues. Receiving a diagnosis, even if it is not a surprise, leads to a journey of emotion, discovery and re-negotiation with oneself and other people. A diagnosis is a substantial piece of information and life event. Don’t think it will be easy even if you are keen to be diagnosed. It is good, but not easy.

I experienced a sense of grief over what might have been and how I might have lived and developed my life. I had a confirmation of what I had believed for 25 years before the diagnosis. But until the diagnosis, there was a vestigial notion that I might be wrong. I spent years knowing, but not wanting finality. I do not know why, I just did.

I have spoken to several adults about their quest for diagnosis, and they reported having a time of knowing and waiting before seeking a diagnosis. What we had in common was a life event that triggered us to seek a diagnosis. Some people attend an autism event, hear about themselves, and then feel strongly they want a diagnosis and confirmation of where they know they are in life. If I had a pound for every time I was approached after training people, speaking at an event or discussing autism with someone, for my opinion about whether they should get a diagnosis, I would have enough money to buy a good meal out, with drinks, for me and my family.

I consistently come across people who have known for years and were making their journey towards a diagnosis. I sometimes join them on their journey and help them decide what to do. A diagnosis works for many people; however, there are a significant number who are content to know they are autistic without seeking a diagnosis. These people always have a reason: a mother who will put everything she has into her autistic child and does not want a distraction from her mission to be the best mum she can be; an elderly person who is happy to have the peace of understanding in their later years; the successful, self-driven person in a busy career who knows they are autistic and feels they are living well—maybe they will seek a diagnosis in future decades? And there is the person who is fine with living as they are and does not see an advantage in a diagnosis, just as there are those who are too busy with life, family and job to take time out for a diagnosis.

I feel for the ones who are so crushed and frightened that they cannot disturb the fragile life they have with the emotional input a diagnosis involves, and the ones who have had bad experiences in education and growing up from being stigmatized because they were different and struggled. These people need love, quiet support and affirmation.

My advice to you would be to reflect on where you are in life. Where would a diagnosis fit into your life? What could your life be like post-diagnosis? What might your family feel? Would a diagnosis help them? You have time to decide. A diagnosis is significant, and life will be different afterwards. I support you whatever decision you make.