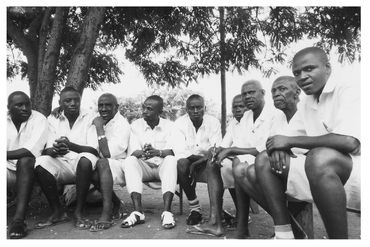

When the interviews were over, I suggested to the gang that we take a photograph of them. I told them it would be published, so that readers could attach faces to their accounts. I thought the men would have reservations, but they readily agreed, except for Adalbert, who refused even to discuss it and was absent on the day the picture was taken. The photo shows them on the benches in the garden where my interviews took place. It’s like one of those commemorative photographs celebrating a departure or the end of something.

From left to right: Joseph-Désiré, Léopord, Élie, Fulgence, Pio, Alphonse, Jean-Baptiste, Ignace, and Pancrace.

JOSEPH-DÉSIRÉ BITERO

He was born on the hill of Kanazi to parents who were farmers, and at the time of the killings he was thirty-one years old. As a cousin of the burgomaster, he had joined the MRND, President Habyarimana’s party, at an early age. He is married and the father of two children who live on the family farmland. A graduate of a teachers’ training college, he taught and lived in Nyamata. He was in charge of the MRND party’s youth movement and in 1993 was named municipal president of the interahamwe, the most important Hutu extremist militia.

As such, he is the only member of the gang to have been implicated in the preparation of the genocide several months before it began. After his conviction, his house in the Gatare neighborhood in Nyamata was confiscated to pay his fines. His wife was not prosecuted, but she has not been able to return to her job at the Sainte-Marthe Maternity Hospital. With her two daughters, she returned to live in a family house in Kanazi to cultivate their fields there.

Accused of crimes of genocide and crimes against humanity with premeditation, Joseph-Désiré was prosecuted individually at a trial in the municipal court of Nyamata that was very closely followed. The court rejected his superficial and contradictory confessions for their lack of sincerity, and he was condemned to death on July 3, 1998. His appeal of the sentence was rejected by the supreme court in Kigali. Because of a delay in his sentencing, he escaped the public execution of April 24, 1998; his probable fate will be life in prison, at least so long as the current régime of President Paul Kagame remains in power.

LÉOPORD TWAGIRAYEZU

He was born in Muyange, on the hill of Maranyundo. He was twenty-two at the time of the killings, a son of farmers, like all

the others in the gang. He has four sisters. He attended elementary school, then worked in the family fields. Like Joseph-Désiré Bitero, he was a member of the MRND, but only for two years, and he had no real responsibilities. He has been a fervent Catholic since childhood.

Accused of crimes of genocide and crimes against humanity, he pleaded guilty to numerous murders and acts committed in his capacity as a cell leader. In 2001 the municipal court in Nyamata sentenced him to seven years in prison. The importance of his confession and the effectiveness of his cooperation with the police and judicial authorities during the preliminary investigation of his case explain why his sentence was lighter than those of his companions. He did not appeal it.

He served almost all of his sentence (having been in prison since 1995) and was released in December 2002 without being sent on to a reeducation camp. His neighbors greeted him with insults and threats during an official ceremony of forgiveness, however, and he has not yet returned to his home on the hill of Maranyundo.

ÉLIE MIZINGE

He was born in Gisenyi, in western Rwanda, near the Congolese border. Fifty years old at the time of the killings, he was quite familiar with the ancien régime, since he was fourteen at the death of the last Tutsi king, before independence. A soldier, he arrived in the Bugesera in 1974 to invest his savings in land and found a suitable plot in Karambo, on the hill of Muyenzi. He left the army, joined the municipal police force, then hung up his uniform to become a farmer in 1992, when he was more or less dismissed in the aftermath of a murder. He is married; two of his three children are dead.

The preliminary investigation of his case is over, but he was

not tried with his friends, doubtless because of his past career as a soldier and policeman. He will probably be brought up before a gaçaça,15 a people’s court, and will likely be sentenced at most to two or three years of community service, which means probation, plus three days of unpaid work each week in a private business or government office. For now he is in the camp at Bicumbi, where he attends civics classes with his comrades. Upon his release, he will await his trial at home, not in prison.

FULGENCE BUNANI

He was born in the Gitarama region, and like all his pals in the gang, he is the son of farmers. Thirty-three years old at the time of the killings, he was thirty-nine when the interviews began. After completing elementary school, he became a farmer in Kiganwa, on the hill of Kibungo. A fervent Catholic, he served as a voluntary deacon during lesser rites in the church in Kibungo and filled in for the priest, who had to minister to several parishes. Fulgence’s wife and two young children live on their plot of land.

Fulgence was one of some forty prisoners tried by the municipal court of Nyamata, which sits in a building near the penitentiary, far from the hills and the town itself. Accused of crimes of genocide and crimes against humanity, he pleaded guilty to aiding and abetting

murder. The court accepted his plea and on March 29, 2002, sentenced him to twelve years in the Rilima penitentiary. He did not appeal the sentence to the supreme court in Kigali. Following the presidential decree of January 1, 2003, intended to diminish the prison population drastically, he was released on January 21 after six years in prison and placed for four months in a reeducation camp in Bicumbi, in northeastern Nyamata. He was released on probation on May 5, 2003, and went home to Kiganwa.

PIO MUTUNGIREHE

He was born in Nyarunazi, on the hill of Kibungo. Twenty years old at the time of the killings, he is unmarried, from a family of four brothers and sisters. He played on the “mixed” soccer team of Kibungo, was a fan of the Bugesera Sports soccer team, and was a dedicated member of the Kibungo Choral Society. After finishing elementary school, he worked in the family fields located between Nyarunazi and Kiganwa.

He was tried along with Fulgence, Pancrace, and Adalbert. He pleaded guilty to certain murders and on March 29, 2002, was sentenced to the same punishment as his friends: twelve years in prison. He did not appeal the sentence. He too was sent to the reeducation camp in Bicumbi for four months and, like the others, was released on May 5, 2003, free and exempt from any community labor, like all those in the gang aside from Élie and Alphonse.

In tiptop shape, he is eager to take up soccer again.

ALPHONSE HITIYAREMYE

He was born in the province of Kibuye, west of Nyamata. In 1977 he was brought to the Bugesera as a hired field worker by a Tutsi landowner. He later bought his own plot of land in Nyamabuye, between the hills of Kanzenze and Kibungo. He also

owned a business in Kanzenze that did well—he has a good head for such things. He was thirty-nine the year of the killings. Married, he is the father of four children. He was a good soccer player and a good Catholic. His wife lives and works on their plot of land.

His judicial situation is unusual. The preliminary investigation of his case was closed, but for no apparent reason he was not one of the forty defendants at the trial of Fulgence, Adalbert, Pio, and the others. He was released on May 5, 2003, but will doubtless be tried by a gaçaça court. Like Élie, he thus risks being sentenced to several years of probation involving community labor. Such jobs may run the gamut from working as a doctor in a dispensary to toiling on a road gang.

JEAN-BAPTISTE MURANGIRA

He was born near Gikongoro, in central Rwanda. He was thirty-eight at the time of the killings. After completing his secondary schooling, he obtained a good civil service position as a census taker and local official, but after losing his jobs, he returned to farming. He is married to a Tutsi, Spéciose Mukandahunga, who was spared during the genocide. This marriage is not a sign of tolerance; many officials and prominent citizens wed Tutsi women for reasons of snobbery. His wife still lives in their house and cultivates their plot of land in Rugunga, a hamlet of Tutsis on the hill of Ntarama. He has six children and has had hardly any news of them.

He was the first of the gang to be tried, only a few months after the Hutus had returned from Congo and before the implementation of the policy of national reconciliation, which doubtless explains his relatively severe treatment by the judges. He pleaded guilty to certain murders and was sentenced on

March 30, 1997, to fifteen years in prison. He did not appeal his sentence with the supreme court in Kigali.

He left the Rilima penitentiary in January 2003 after eight years in prison and was sent to the reeducation camp in Bicumbi. At his release on May 5, 2003, he returned home to his Tutsi wife and his land, where he is waiting for a civil service job in Ntarama, Nyamata, or elsewhere.

IGNACE RUKIRAMACUMU

He was born in the area of Gitarama and was sixty-two years old at the time of the killings. Like Élie, he experienced life under the Tutsi monarchy, since he was just shy of thirty when the republic was founded and independence achieved. He arrived in the Bugesera in 1973. After finishing his fourth year of elementary school, he worked as a mason, then acquired a plot of land in Nganwa, on the hill of Kibungo. His wife is dead. Several of his children were killed after the genocide, but he does not have precise information about any of them.

The preliminary investigation of his case is over, and he will not be tried. Following a presidential decree concerning prisoners above the age of seventy, he was released, unconditionally, on January 21, 2003.

He was thus the first member of the gang to be freed. He is back cultivating his fields in Nganwa, is already distilling urwagwa again, frequents the Saturday market, and is getting used to a new cabaret, since the one he patronized before the killings was destroyed. He talks very little about his recent past.

PANCRACE HAKIZAMUNGILI

He was born in Ruhengeri, on the hill of Kibungo, the year his parents came from Gitarama to the Bugesera. He was twenty-five

the year of the killings. By his own admission, his talents run more to chatting with friends in the local cabaret than to religion. He is an unmarried farmer with four brothers and sisters. His mother manages the work on the family’s land.

Pancrace was among the forty prisoners tried along with Fulgence. He pleaded guilty to certain murders, and his pleas were accepted. He was sentenced the same day as Fulgence to the same punishment: twelve years in prison, a sentence he did not appeal. He too was released from the penitentiary in January 2003, spent four months in the camp at Bicumbi, and became a free man on May 5, 2003.

ADALBERT MUNZIGURA

His parents left Gitarama for the Bugesera in 1970, settling on the hill of Kibungo to begin farming in Ruhengeri, where Adalbert was born. He was twenty-three at the time of the killings. Adalbert is unmarried. Out of his eleven brothers and sisters, the family is sure that seven are still alive. He finished elementary school before going to work in the family fields. He was the choirmaster in Kibungo and a member of the Democratic Republican Movement, a Hutu nationalist party and the MRND’s chief rival for power.

Tried along with Fulgence and Pancrace, he pleaded guilty to certain murders. His succinct confession was accepted by the court, to the great displeasure of certain judges and the lawyers of plaintiffs claiming damages. He was sentenced to twelve years in prison. He made no appeal.

On the day of the verdict, the public prosecutor in Nyamata announced that he might file an appeal a minima, on the grounds that the sentence was too light and failed to reflect the convicted man’s responsibilities as the head of a death squad and his active

role both before and during the massacres. This prosecutorial appeal was subsequently dropped without explanation.

So Adalbert left the penitentiary at the end of January 2003 for the camp at Bicumbi. On May 5, 2003, he too was released to go home to Ruhengeri, where he was impatiently awaited by his mother, Rose Kubwimana.