4

Bonds and Inflation

“In economics, interest rates act as gravity behaves in the physical world.”

—Warren Buffett, Warren Buffett on the Stock Market

Introduction

In the prior chapter, we took some “baby steps” into the world of investing, discussing investment products available at most banks, things such as savings accounts and CDs. In this chapter, we'll expand into other types of investments, mostly bonds, a term introduced in the last chapter that we will expand upon here. A bond is a loan, or an IOU. Bonds don't result in the company giving up a piece of ownership in itself, which occurs when they sell stock. Why do companies or governments issue bonds? Mainly to raise money to pay for things such as recurring operations or to expand.

Bonds don't necessarily have to be boring. For example, later in this chapter, we'll discuss bonds that were issued by the late rock star David Bowie. Not surprisingly, they're called Bowie Bonds. Bonds usually fall under the heading of fixed income securities. This name is derived from the fact that the amount and timing of the cash or income you get from owning most bonds are fixed. Of course, there are exceptions, and we'll cover some of them too.

Although stocks get all the hype, bonds will probably play a bigger role in the lives of most people. The global bond market is also bigger than the stock market, so it's of enormous importance to how the world runs. You've probably heard the Dunkin' Donuts slogan, “America runs on Dunkin.” Well, the global financial markets to a great extent run on bonds, which are a form of debt, or borrowed money. Most people own their home with the help of a mortgage, where you pay cash for part of the purchase price and borrow the rest. That's debt, and that's a bond. If you have a student loan, it's valued like a bond. A car loan is the same thing. Basically, anything that has regular cash payments attached to it can be turned into a bond.

US Savings Bonds

A type of bond that you've most likely seen is a US Savings Bond issued by the United States Treasury—the branch of the federal government that is responsible for its finances and collecting taxes. Maybe you received a savings bond as a gift at some point in your life. In the past, the buyer typically paid half the face value of the savings bond, and the holder eventually got to cash it in for the full amount. The face value is literally the amount that it says on the paper or physical bond. For example, perhaps you received a $50 US savings bonds as a gift in the past. The person who gave you the gift probably paid $25 for it. Maybe you were fooled into thinking they paid $50 for it, but any gift is a nice gift, regardless of how much was paid for it.

However, in 2012 the US Treasury ditched the paper bonds. Now, they are all virtual or electronic. One reason why the US Treasury did this is that the new electronic ones are easier to track. The reason for buying a bond, of course, is the interest that you'll earn. Both the old paper bonds and newer electronic bonds pay interest. Not a lot, but it's another one of those rock-solid investments that you can “take to the bank.” The bonds are backed by the “full faith and credit of the US government.” That means you're virtually guaranteed to get paid. The US government can always run the money printing press or tax its citizens to pay its bills.

The most common type of US savings bonds are called Series EE Savings Bonds. There is a less popular US Savings Bond, called Series I, which we'll discuss later in this chapter. As you might have guessed, the I stands for inflation. The minimum purchase amount for a US Savings Bond is $25, and the maximum purchase is $10,000 per calendar year for each Social Security number. You can buy them, without paying any commission or transaction fees, directly from the US Treasury at TreasuryDirect.gov.

As with a CD, your money is “locked up” for a while, or else you have to pay a penalty. You can cash them in after 1 year, but if you cash them in before 5 years, you lose the last 3 months of interest. For example, if you cash a Series EE bond after 2 years, you get the first 1 year and 9 months' worth of interest. You can hold them as long you want, but they stop paying interest after 30 years. The US Treasury determines the interest rates offered on its EE Savings Bonds semi-annually, on May 1 and November 1.

There are some modest tax advantages to buying US savings bonds, at least when you make enough money to be required to pay taxes. You have to pay federal government taxes on the interest earned on savings bonds, but they are exempt from state and local taxes. Some lucky people living in states such as Florida, Texas, and Washington have no state income tax. Others, living in states such as California, Oregon, Minnesota, New York, New Jersey, and Iowa have a top state income tax rate of 8% or more. Some cities, such as New York City, charge additional income taxes to their residents. So paying taxes on Series EE bonds may not be a big concern for you for a while, but it may be someday, especially if you heed Buffett's advice for building long-term wealth.

Other US Treasury Fixed Income Securities

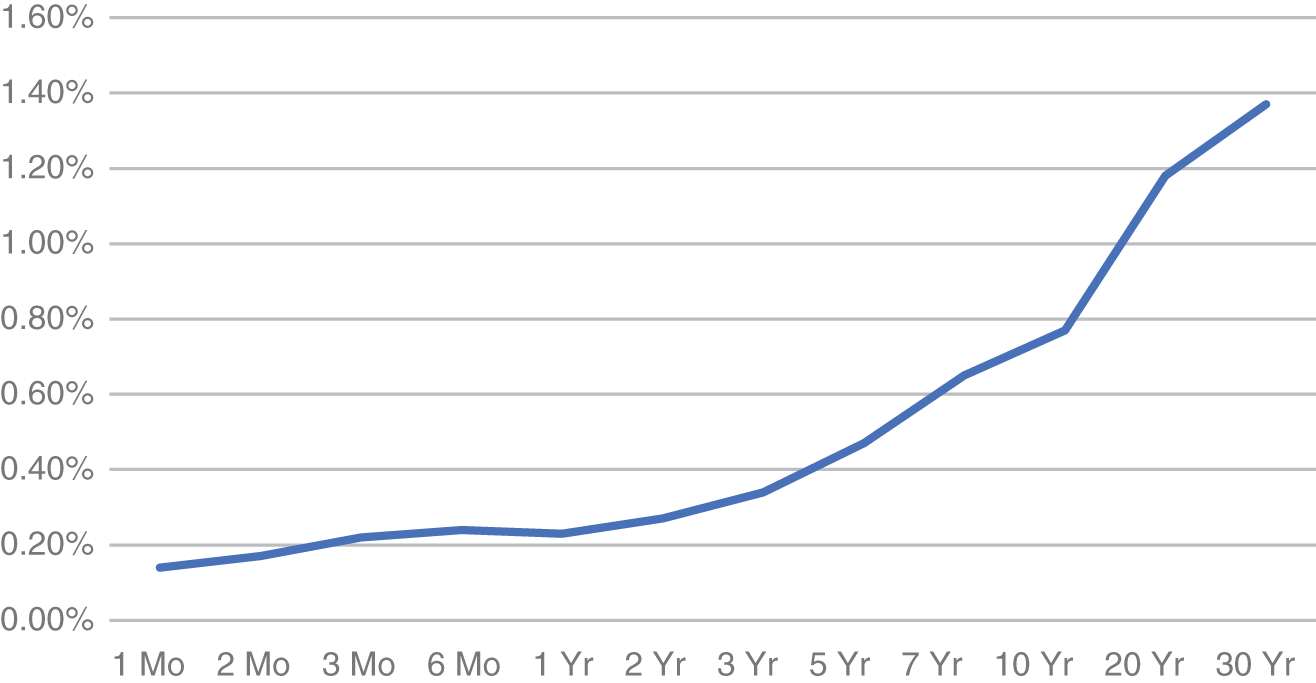

Some people who hear the words “interest rate” think it's a single number that applies to all fixed income securities. It's not. There's a whole range of interest rates ranging from short-term (usually about 1 month) to long-term (usually up to 30 years) maturity dates. In addition, riskier borrowers will have to pay higher rates across this maturity spectrum. Historically, long-term interest rates are higher than short-term rates because long-term bonds usually have a greater chance of a loss, but it's not always the case. The relationship between time to maturity and the interest rate, known as the yield to maturity in bond lingo, is called the yield curve. Sometimes it goes by the fancier academic term, the term structure of interest rates, especially when listed in a tabular format. We'll stick with yield curve. A picture is shown in Figure 4.1.

The shortest term issued US Treasury securities are called US Treasury Bills, or T-bills for short. They mature or expire in one year or less. T-bills are issued for periods of 28, 91, 182, and 364 days. You can hold them beyond their maturity date, but they won't gain any additional income or accrued interest, a term which also refers to interest that gathers between payment dates. They are sold below or at a discount to their face values, typically $1,000. For example, if the interest rate is 1%, a 364 day T-bill, using our Present Value formula from Chapter 2, would sell for about $990.10, when it's issued. You can collect the money when the T-bill matures: $1,000 in our example. T-bills are usually the safest and most liquid of all fixed income securities. As we mentioned in the last chapter, it's what Buffett uses for his rainy-day fund.

Figure 4.1 The U.S. Treasury Yield Curve, April 2020

Source: From DOT, U.S. Treasury Yield Curve, April 2020, U.S Department of Treasury

US Treasury notes (T-note for short) are fixed income securities issued by the US government that mature, when issued, between 1 and 10 years. The most common ones issued are the 2-year and 10-year US Treasury notes. US Treasury bonds are securities issued by the US government that mature, when issued, in more than 10 years. The most common ones issued are 20-year and 30-year US Treasury notes. There isn't a meaningful difference between a Treasury note and Treasury bond, other than the maturity dates. They both pay interest semi-annually, or twice a year, and usually have a face value of $1,000. The amount of interest paid on a bond (e.g., $50) is known as the coupon. If it's expressed as a percentage (e.g., 5%), it's called the coupon rate. Most bonds have a coupon rate that is fixed for the life of a bond and a face value of $1,000. These are often called “plain vanilla” bonds since they are the most common, like vanilla ice cream within the ice cream universe.

The last major type of US Treasury security aims to protect its holders from inflation. They're called Treasury Inflation Protected Securities, or TIPS for short. We previously discussed inflation as having a negative effect on your purchasing power, or ability to buy things. For example, today $10 might be enough to get you a decent meal at Chipotle, Shake Shack, or your favorite fast casual restaurant. But 20 years from now, the odds are that $10 might only be enough to pay for your drink at the same restaurant. TIPS are tied to inflation. When inflation goes up, your interest payment from the TIPS bond goes up too. When the interest payment or coupon on a bond changes, it's known as a floating-rate bond. Most bonds have fixed coupon payments, but floating-rate bonds are out there as well. The most common floating-rate benchmark is called London Inter-bank Offered Rate (LIBOR), which is determined as an average of interest rates posted daily by a group of banks in London.

In essence, TIPS protect you to a great extent from the ravages of inflation. TIPS are currently offered in 5-year, 10-year, and 30-year maturities. You might think, “If these bonds protect you from inflation, why don't all investors buy them?” Since it is close to a risk-free rate of return, they pay low rates of interest. For example, a 5-year TIP was recently yielding a paltry 0.16% annual rate of interest. No one is going to get rich earning less than 1% a year, even after inflation. Since inflation is such an important topic, according to Buffett, we'll give it its own section in this chapter.

Inflation and the Consumer Price Index (CPI)

The prices of most new things go up in value over time, historically about 2% or 3% per year. We call this process inflation (Chapter 1). In some cases, prices fall, and when they do, it's called deflation. Deflation might occur due to oversupply or falling demand for something, or because it becomes cheaper to manufacture. For example, Tesla's early cars often cost more than $80,000 each. However, after their “gigafactory” was up and running, they were able to sell their Model 3 car starting at $35,000. Still a lot of money, but by producing batteries in bulk, they were able to drive down the cost of some of their cars.

We can say inflation means rising prices, but we need to measure it more precisely in order to make good financial decisions. The most common way is by calculating a Consumer Price Index (CPI). The CPI represents a basket of goods and services purchased by the typical American household and is calculated by a unit of the US government, the Bureau of Labor and Statistics (BLS). Different countries will have their own inflation measures. There are different parts to the US basket, as shown in Figure 4.2.

The biggest part of CPI for most households is where you live, or housing. That's typically about 40% of someone's spending. Other big parts are transportation, such as the cost of having a car or commuting to work, and medical care. But your own personal CPI may differ dramatically from the BLS's calculation. For example, many young people live at home or at college, where part or all of the expenses are paid for by their parents. Their biggest current spending items are probably related to food, clothing, and entertainment. However, as people age and move out on their own, housing, health care, and transportation will probably occupy the bulk of their spending.

The BLS publishes the CPI monthly and periodically updates the components of the CPI basket and its weights. For example, there were no cell phones 50 years ago, and very few people had their own computers. Typewriters and the buggy whip have largely disappeared from today's modern economy. So the CPI changes represent the ebb and flow of the economy and what is purchased by its survey of thousands of US households.

Bond Ratings and Corporate Bankruptcy

Companies such as Apple, Disney, and Nike also issue bonds. Unlike the US government, however, they can't run the money printing press to pay their bills. There's a chance that they won't pay what's promised in terms of the interest payments or principal. The chance they don't pay on time or in full is called default risk. The percentage of bonds that default is called the default rate. Just as with individuals (e.g., Buffett vs. you) companies differ widely in terms of their wealth and ability to pay their debts.

Fortunately, you don't have to be a bond guru to get an estimate of a company's ability to pay its bills. There are companies, called rating agencies, that do it for many companies and governments on a global basis. The largest bond rating agencies in the US are Standard & Poor's (S&P), Moody's, and Fitch. We'll see the S&P name again in the context of stocks, so file it away for now. They rate bonds with a combination of letters. They differ slightly in their nomenclature, so we'll stick with the one S&P uses. The best rating is AAA. It might surprise you that there are only two companies in the US with a AAA rating today (Microsoft and Johnson & Johnson). Below AAA is AA+, then AA, AA–, A+, A, A–, BBB+, BBB, and BBB–, plus some others. Bonds rated BBB– and higher are called investment grade bonds. Bonds rated below that, BB+ all the way through D, are called high yield or junk bonds. Why would someone buy junk bonds? They offer higher rates of interest, convincing some investors that they're worth the risk.

Figure 4.2 Consumer Price Index Components

Source: Data from Relative importance of components in the Consumer Price Indexes: U.S. city average, December 2019.

Why do investment analysts make the distinction between investment grade and junk bonds? Some investors are prevented from owning junk bonds, so they aren't for everyone. If fact, Buffett would say they rarely make sense for anyone. Buffett is not a fan of newly issued junk bonds but will occasionally buy some when they get really, really cheap. In his 1990 letter to shareholders, Buffett wrote, “Junk bonds remain a minefield, even at prices that today are often a small fraction of issue price. As we said last year, we have never bought a new issue of a junk bond. (The only time to buy these is on a day with no “y” in it.) We are, however, willing to look at the field, now that it is in disarray.”

The default rate for all bonds historically averages around 1.5% per year. But the number is higher during recessionary periods in the economy and lower during expansionary periods. And, as you might guess, the default rates differ for investment grade bonds versus junk bonds. If the overall default rate is 1.5% in any given year, roughly 4% of junk bonds default and less than ½ of 1% of investment grade bonds default.

A D rating means default, which means the company didn't pay what it promised. In many cases the firm is, or will be, in bankruptcy. Bankruptcy can apply to corporations and even some governments, just like we discussed with individuals in the last chapter. It might surprise you, but some companies can still operate while they are in bankruptcy. There are two major types of corporate bankruptcy, Chapter 7 and Chapter 11.

In Chapter 7, the firm sells whatever it can and gives the net amount to its creditors (i.e., the investors that purchased the firm’s bonds and, rarely, stockholders) and then ceases to exist. The Chapter 7 process is known as liquidation. You may recall the electronics store Circuit City or the online music download service Napster. These companies have disappeared.

A Chapter 11 bankruptcy allows the firm to continue to operate. Some of its debt is usually eliminated, while other parts are restructured. In most cases the old stockholders are wiped out and the new shareholders are often the original bondholders who didn't get paid in full. The recovery rate is the amount of money (e.g., 70 cents on the dollar) that the old bondholders receive during the Chapter 11 process. Since they are usually taking a significant loss or haircut, they are often given stock in the new, reorganized firm. You've certainly come across companies that went through the Chapter 11 process, even if you weren't familiar with the term. Examples include General Motors (GM), Chrysler, Macy's, Aéropostale, Sears, and Delta Airlines.

Corporate Bonds, Municipal Bonds, and Bowie Bonds

Corporate bonds are issued when companies borrow money from investors. They can also borrow money from banks, which is often called a term loan. Both types are debt obligations of the firm. We mentioned Apple, Disney, and Nike in the last section, but literally thousands of companies sell bonds to investors. Just as with US Treasuries, the borrowings may be short term in nature (i.e., less than 1 year) or long term (i.e., up to 30 years). It's often the cheapest way for them to fund their businesses, pay for the development of new products and services, or buy other companies. In Chapter 7, we'll cover the basics on accounting, but for now, we'll tell you that there is a tax advantage for companies issuing debt. The interest they pay on their bonds is tax deductible, meaning it lowers their tax bill.

State and local governments may also issue bonds, which are known as municipal bonds, or munis. For example, the government of the state that you live in likely sells debt to investors and uses the money to help pay for various things, such as schools, roads, the state police, health care services, and many other items. Your local school district may issue municipal bonds that help pay for the building of schools and teacher salaries. State colleges and universities often issue municipal bonds. Municipal bonds are usually very safe, but occasionally, there are bankruptcies, as once occurred with the city of Detroit and the US territory of Puerto Rico.

There is also a big tax benefit to municipal bonds. Buyers pay no federal income taxes on the interest they receive from the bonds, unlike US Treasuries, which are taxable to individuals. This is one of the few legal ways you can avoid Ben Franklin's quote on the inevitability of death and taxes. And if you live in the place where the bonds are issued, you are also exempt from paying taxes on the interest to state and local governments. For example, if you live in New York City and purchase a New York City school bond, the interest is exempt from federal, state of New York, and New York City income taxes. The tax deductibility of municipal bonds is also a great benefit to the issuer of the bonds (e.g., a school district) since they can pay their investors lower interest rates than would be the case if the bonds were fully taxable.

Bowie Bonds and Other Asset-Backed Securities

We mentioned that almost anything that has a cash flow tied to it can be turned into a bond. When a song is played on the radio, or through some other broadcast mechanism, the composer of the song is entitled to a small royalty. If you are a best-selling recording artist, like Taylor Swift, U2, Drake, Beyoncé, The Beatles, or David Bowie, these royalties can add up to millions of dollars per year. David Bowie was the first recording artist to monetize his music royalties by issuing a bond, with what became known as Bowie bonds.

The bonds were issued back in 1997 and were based on the royalties from 25 David Bowie albums recorded before 1990. The bonds raised $55 million and had a life of 10 years at an interest rate of 7.9%. Later, other artists followed suit with their own bonds, including James Brown, the “Godfather of Soul.” Marvel, now owned by Disney, once issued bonds backed by the rights to some of its comic book characters, such as Captain America. Bonds backed by specific things, such as music royalties, comic book characters, auto loans, and many other items, are known as asset-backed securities.

The Federal Reserve: The Central Bank of the United States

To better understand what drives interest rates and bond prices, we need to discuss a country's central bank. A central bank may be viewed as the “banker's bank.” It can provide money for banks when they get in trouble and it also oversees, or regulates, banks. It also determines how much money a country should print. The Federal Reserve, or “The Fed,” is the central bank of the US. Most other countries, or economic regions, also have their own central bank. For example, there is the Bank of Japan (BOJ), People's Bank of China (PBOC), Bank of England (BOE), and the European Central Bank (ECB). The ECB helps manage the money supply for those countries that are part of the euro currency.

The Fed is a quasi-independent unit of the US government, meaning they are a part of the government but run independently. The leadership of the Federal Reserve is known as Federal Reserve Board of Governors. But they don't run for election. They are appointed by the president for terms of 14 years and confirmed by the US Senate, with the chance of renewal. The long-term nature of their appointments provides them with some independence, since the US president cannot be elected for more than two 4-year terms. The head of the Fed's Board of Governors is its chairperson, currently Jerome Powell. The chair is appointed for 4 years, but the term may be renewed at the president's discretion. Some Fed chairpersons have served for almost 20 years.

The Fed has two main goals. The first is to maximize employment, or alternatively, to minimize unemployment. The unemployment rate can never be zero due to a mismatch of skills between the job openings and the skillset of those applying for jobs, as well as the unawareness of job openings or candidates, and the difficulty of relocating to the areas where the jobs are available. Full employment varies by country, but in the US it is estimated to be about 97%, or 3% unemployed.

The second main goal is to have stable prices, generally believed to have inflation average about 2% per year. You might ask, “Why should there be any desired inflation?” You can view money as the lubrication of the economic system. Just like a gasoline-powered engine needs oil to run smoothly, an economy needs money to be clicking on all cylinders. A little bit of extra money helps take into account things such as population growth and helps avoid the fear that money is “tight” or scarce. These two main goals, maximum employment and stable prices, are known as the Fed's dual mandate. It has other lesser goals as well, such as a strong economy and stable interest rates, but they are closely related to the dual mandate.

The Fed tries to achieve its goals through three main techniques. The first is related to a bank's reserve requirements. This term refers to how much money a bank has to keep in the vault, either literally or electronically on reserve with the Fed. It might surprise you, but if you deposit, let's say, $100 in the bank, the bank doesn't put all of it in the vault. It puts about 5% to 10% in the vault and then lends out the rest to companies or individuals seeking loans. This is why there is no bank that can survive a run on the bank, which means many of the bank's customers simultaneously request their money back. The Fed will step in during any run on a bank to help stabilize it. Occasionally, like in the Great Recession of 2008–2009, the Fed will allow some banks to fail, but it will make sure that all FDIC-insured deposits are safe, as we mentioned in the last chapter.

The second main tool that the Fed uses is to change short-term interest rates. Specifically, it sets the rate for what's known as the federal discount rate. The federal discount rate is the interest rate charged when banks borrow from the Fed. Since banks lend money to their customers, it's often used as a base rate of interest for short-term loans. When the Fed raises or lowers the federal discount rate, banks usually promptly follow suit with the interest rates they give to their customers. Bank customers usually are charged a rate higher than the federal discount rate due to the credit risk (i.e., chance of not making payments on time), a term we mentioned earlier in the chapter. The best customers of the bank pay what's known as the prime rate. Other customers pay higher rates. In short, the Fed helps control short-term interest rates through its changes to the federal discount rate. In the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Fed slashed the discount rate to 0% in an effort to spur economic growth.

The Fed's third tool is called open market operations, which means its policy of buying and selling securities. It usually buys or sells US government bonds, or bonds indirectly backed by the US government, such as mortgage-backed securities. The act of buying injects money into the economy and generally lowers interest rates, especially those of the intermediate- to long-term part of the yield curve. It goes back to our supply and demand diagram discussed in Chapter 2. If there is additional demand buying bonds and the supply is roughly fixed, it winds up lowering interest rates and pushing up the price of bonds.

We'll cover this concept more in the next section, but one factoid to remember is that when interest rates go down, the price of most bonds go up. The reverse is also true (i.e., when rates go up, bond prices go down). When the Fed buys a lot of bonds, it's generally referred to in the financial press as quantitative easing, or QE. QE generally results in lower interest rates and is often used by central banks when short-term rates are close to zero. To fight off the recession triggered by the COVID-19 panic, the Fed is literally buying trillions of dollars of securities over the 2020–2021 period through its QE program.

Lower interest rates generally speed up economic growth, while higher interest rates generally put the brakes on economic growth. You might be thinking, “Why would a central bank want to put the brakes on economic growth?” To avoid too much inflation, which means the economy is in danger of overheating and heading into a recession.

What Determines Interest Rates?

There are several factors behind the level of interest rates. The behavior of The Fed, or the central bank of a country, is a big influence. But there are other factors as well. Economic growth is generally tied to the level of interest rates. During strong periods of growth, both companies and individuals often need access to funds. Companies might need money to pay for new projects they have planned. Individuals might need money for homes, cars, and other spending plans. So during strong periods of economic growth, interest rates are usually higher since demand is high. During weak periods of economic growth, rates are usually lower since demand is low.

The financial markets are global, so interest rates in another country, adjusted for currency conversion rates (e.g., US dollars for euros), also affect the level of interest rates. For example, if the rates on bonds of similar riskiness are higher in the US than in Europe, European investors would move money out of Europe and into the US. Using the supply and demand dynamics we previously discussed, this behavior would generally result in slightly lower US interest rates and slightly higher rates of interest for economies using the euro. Investor sentiment or market psychology also plays a role in interest rates and prices. Usually, when there is a lot of fear, due to some financial crisis or shock to the economic system, people gravitate toward safe securities, such as US government bonds. This “flight to quality” behavior generally lowers interest rates in most countries with strong credit ratings.

We can explain after the fact what moved bond prices. Forecasting them in advance is a hard task and almost impossible over the short term. In his 1980 letter to shareholders, Buffett wrote, “We believe that short-term forecasts of stock or bond prices are useless. The forecasts may tell you a great deal about the forecaster; they tell you nothing about the future.” A pretty harsh but likely accurate criticism. We've waited a while in this chapter for a Tip, so this quote will be our first for the chapter.

Intuition on Estimating the Price of a Bond

As mentioned previously, we're going to keep the math to a minimum, with any equations put in the Appendix or endnote if they can't be explained in plain English. We'll give you the intuition for valuing a bond in this section and put the specific formula for bond valuation in the Appendix. Recall, from Chapter 2, the Present Value formula says how much you would pay today to receive a cash flow, such as $100, in the future. Well, with a bond, there are two types of cash flows. The coupon (aka interest) payment and the face value (aka principal). The price of the bond is simply the present value of these two groups of cash flows (i.e., coupon payments and face value).

As noted earlier in the chapter, the discount rate on a bond is called the yield to maturity. It's a market-determined rate that changes slightly each day. The difference between the (fixed) coupon rate and (floating or market-based) yield to maturity helps explain why the price of the bond isn't always $1,000, or its face value.

When a bond is first sold to investors, the coupon rate is usually close to the yield to maturity. But it can drift over time since the yield to maturity is determined by market forces, while the coupon rate is always fixed, unless it is a floating-rate bond. We can give you some good rules of thumb for bond valuation without any equations.

If the coupon rate equals the yield to maturity, the price estimate for a bond always equals its face value. That is, $1,000 in most cases, which is known as at par in bond lingo. If the coupon rate is higher than the yield to maturity, then the price of the bond will sell for more than its face value and is known as a premium bond. The intuition is that the coupon rate is higher than the market rate, therefore the bond should be more valuable since it gives you more interest than is expected and therefore should sell for a higher price. If the coupon rate is lower than the yield to maturity, then the price of the bond will sell for less than its face value, or what's known as a discount bond. The intuition is that the coupon rate is lower than the market rate, so it should sell at a discount.

A key aspect to plain vanilla bond prices is that they move in the opposite direction of interest rates. That is, when interest rates go up, plain vanilla bond prices go down. And when interest rates go down, the prices of plain vanilla bonds go up in value, other things equal. Or as Buffett said, “In economics, interest rates act as gravity behaves in the physical world.” It's a play on the old expression, “What goes up must come down.” Buffett's point is an important one, so we'll add it to our growing pile of tips.

When interest rates fall (rise), it means the bond is less (more) risky. If it's less (more) risky, you should be willing to pay more (less) for it. Sorry for all those parentheses! We know certain things about bonds can be really boring, like an opera concert for a heavy metal fan!

Another point to be aware of is that bonds that have high coupons are generally less risky than bonds with low or no coupons. The coupons act as sort of a “cushion” to help offset changes in interest rates. And, as we mentioned earlier in the chapter, long-term bonds are generally riskier than short-term bonds. They move around a lot more when interest rates change. It doesn't mean that you wouldn't own them, but rather, you'd want them at a good price or when you think interest rates are going to go down. Putting these two concepts together, long-term low or no coupon bonds are the riskiest, and short-term high coupon bonds are the safest.

So Are Bonds Good Investments?

We're almost to the end of this chapter, so let's talk about the role of bonds in your financial portfolio. If you need the money for short-term purchases and can't afford to lose money, then yes, bonds, CDs, and savings accounts are probably good investments. They would fall into the “safe haven” category of investments that usually hold up, when the stock market or economy are having problems. However, according to Buffett, if you are trying to build wealth and have a long-term horizon, bonds are generally not good long-term investments. In fact, they may destroy your wealth, after taking inflation and taxes into account. We cite a fairly long quote from Buffett's 2011 Chairman's Letter to Berkshire Shareholders to prove our point:

Investments that are denominated in a given currency include money-market funds, bonds, mortgages, bank deposits, and other instruments. Most of these currency-based investments are thought of as “safe.” In truth, they are among the most dangerous of assets… . Over the past century these instruments have destroyed the purchasing power of investors in many countries, even as the holders continued to receive timely payments of interest and principal. This ugly result, moreover, will forever recur.

Governments determine the ultimate value of money, and systemic forces will sometimes cause them to gravitate to policies that produce inflation. From time to time such policies spin out of control. Even in the US, where the wish for a stable currency is strong, the dollar has fallen a staggering 86% in value since 1965, when I took over management of Berkshire. It takes no less than $7 today to buy what $1 did at that time. Consequently, a tax-free institution would have needed 4.3% interest annually from bond investments over that period to simply maintain its purchasing power. Its managers would have been kidding themselves if they thought of any portion of that interest as “income.”

For tax-paying investors like you and me, the picture has been far worse. During the same 47-year period, continuous rolling of US Treasury bills produced 5.7% annually. That sounds satisfactory. But if an individual investor paid personal income taxes at a rate averaging 25%, this 5.7% return would have yielded nothing in the way of real income. This investor's visible income tax would have stripped him of 1.4 points of the stated yield, and the invisible inflation tax would have devoured the remaining 4.3 points.

A summary of this quote merits a Tip.

This Tip is a fairly controversial point among investors, but we think he's right. There may be select periods of time, as in the early 1980s when interest rates were in the teens, when owning bonds may make great financial sense over the long term. Recall, one of our lessons in this chapter is that when interest rates fall (like they are apt to do when they're very high), bond prices go up. But the greatest investor ever knows what he's talking about when it comes to the Benjamins. As you might guess, Buffett is a big fan of stocks as a way of building long-term wealth, and we'll talk about them over the next two chapters.

A Note on Negative Bond Yields

It's been a crazy decade or so for the bond market, especially when you look on a global basis. The yields on debt from many sovereign nations, such as Switzerland, Japan, Germany, and Denmark, have been negative in recent years! That means you are guaranteed to lose money on the investment if you hold them until the maturity date. What is going on here? Why would anyone buy an investment that is guaranteed to lose money if held to maturity?

First, the negative yield comes from buying a bond at a price greater than its face value. The coupon rate paid on the bond is often too small to overcome paying such a high price to start. The two parts together, coupon plus the difference between the purchase price and sale price help determine your total return. Investors may buy bonds with a negative yield since it is a safe, liquid place to park money. By safe, we mean that the prices won't fluctuate much, unlike a stock or something like Bitcoin. The modest loss incurred by buying these bonds may be viewed as akin to a small tax for these investors. In the US, T-bills were briefly, slightly negative during the Great Recession and during the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, it's a peculiar footnote in the investing world that is slightly more common than a Loch Ness Monster sighting, at least in the US. We and Buffett certainly wouldn't recommend putting a lot of your wealth in something poised to lose money over the long term, regardless of the perceived safety.

Appendix

In this Appendix, we'll cover a quantitative formula for valuing bonds. As we discussed in the main body of the chapter, we're simply going to value the bond as the present value of the coupon payments and the present value of the face value. Most bonds pay interest semi-annually, but to simplify the calculation, we'll assume interest is paid once a year. Let's assume our bond matures in 3 years, its coupon rate is 5%, and its face value is $1,000.

We need the discount rate for the bond, which we mentioned is called the yield to maturity. As a reminder, the coupon rate is fixed for “plain vanilla” bonds for the entire life of the bond. However, the yield to maturity is a market rate that changes a bit virtually every day. The difference between the (fixed) coupon rate and the changing yield to maturity helps explain why the price of the bond isn't always equal to $1,000, or its face value.

Getting back to our numerical example, let's assume the yield to maturity on the bond is 4%. In practice you can get this number by looking at bonds from the same industry with a similar credit rating. We'll do a simple example that is possible to do by hand or with a basic calculator, but in practice most analysts use Excel or a financial calculator.

Recall, our Present Value formula takes the cash flow we expect in the future and discounts it by (1 + r)T, where r is the discount rate (yield to maturity for a bond) and T is the time in years for the bond to mature. In our example, we have four cash flows. The first three cash flows are the coupon payments, $50 a year, or 5% of the $1,000 principal. And then at the end of 3 years we get back the $1,000 principal. Since, in year 3 we get the $50 coupon and $1,000 principal value, we'll add the two numbers in our example. The yield to maturity is 4% and the number of years to maturity, T, is 3.

Presto! We have our estimate for the price of this specific bond, which is $1,027.75. If the price of the bond is selling in the market for less than this price, we'd think it's a good buy and purchase it. If the price of the bond is selling in the market for more than this price, we'd think its overvalued and likely sell it if we already owned it or avoid it, if we had no prior position.

References

- Buffett, Warren. “Letter to Shareholders of Berkshire Hathaway Inc.” Berkshire Hathaway, Inc., 1980. https://www.berkshirehathaway.com/letters/1980.html.

- Buffett, Warren. “Letter to Shareholders of Berkshire Hathaway Inc.” Berkshire Hathaway, Inc., 1990. https://www.berkshirehathaway.com/letters/1990.html.

- Buffett, Warren. “Letter to Shareholders of Berkshire Hathaway Inc.” Berkshire Hathaway, Inc., 2011. https://www.berkshirehathaway.com/letters/2011.html.

- “Comparing Series EE and Series I Savings Bonds.” Treasury Direct. Accessed June 14, 2020. https://www.treasurydirect.gov/indiv/research/indepth/ebonds/res_e_bonds_eecomparison.htm.

- Espiner, Tom. “‘Bowie Bonds’—the Singer's Financial Innovation.” BBC News. BBC, January 11, 2016. https://www.bbc.com/news/business-35280945.

- Kaeding, Nicole. “State Individual Income Tax Rates and Brackets for 2016.” Tax Foundation, February 8, 2016. https://taxfoundation.org/state-individual-income-tax-rates-and-brackets-2016/.

- Kenny, Thomas. “How Likely Is It That a Bond Will Default?” The Balance, January 27, 2020. https://www.thebalance.com/what-is-the-default-rate-416917.

- Leinfuss, Nancy. “Entertainment Royalty ABS Seen Gaining Momentum.” Thomson Reuters, January 19, 2007. https://www.reuters.com/article/financial-assetbackeds-entertainment/entertainment-royalty-abs-seen-gaining-momentum-idUSN0845429320061109.

- Mislinski, Jill. “Inside the Consumer Price Index: May 2020.” Advisor Perspectives, June 10, 2020. https://www.advisorperspectives.com/dshort/updates/2017/06/14/what-inflation-means-to-you-inside-the-consumer-price-index.